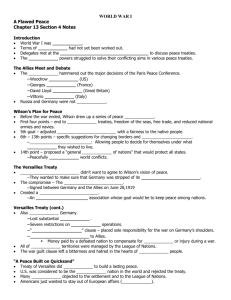

The Inside Story Of The Peace Conference-Dr EJ Dillon-1920-526pgs-POL.sml

advertisement