Notice: This material may be protected by

copyright law (Title 17 U.S. Code)

Pursuant to the federal copyright act (Title 17 of the United

States Code), it is presumptively unlawful to reproduce,

distribute, or publicly display any copyrighted work (or any

substantial portion thereof), without the permission of the

copyright owner. The statute, however, recognizes a fair use

defense that has the effect of excusing an act of copyright

infringement. It is the intention of the library to act within the

parameters of the fair use defense in allowing limited posting of

copyrighted materials in Electronic Course Reserve areas such

as this one. It is the intention of the library, moreover, that such

materials be made available solely for the purposes of private

study, scholarship, and research, and that any further

reproduction of such materials by students, by printing or

downloading, be limited to such purposes. Any further

reproduction of copyrighted materials made from this computer

system may be in violation of copyright laws and is prohibited.

Chapter Three

3

P RO LO G U E:

The Start of Life: G e netics

and Prenatal Deve lo p me nt

TH E F UTU R E I S N O W

It came out of the blue: Jana and To m Mon aco's seem i ngl y healthy

3-year-old son Steph n developed a l i fe-threaten i n g stomach virus

that led to severe brain damage . His d i agnosis: a ra re b u t t reatable

di ease called isovaleric acidemia ( I VA ) , marked by the body'

inabili ty to metabolize an am ino acid fo u n d i n dietary protein.

Jana and Tom were unkn owing ca rrier of the d i sease . . . . The

Monacos had no warn i n g whatsoever.

N ot so when Jana got p regnant again. Her da ughter, Caro l i ne,

was tested by amnjocen tesis while still in the womb. Knowing ar­

oline had the mutation, doctors were able to ad m i n i ter med ica­

tion the day he was born-and the Monacos were prepared to

monitor her diet i mmediately to keep her healthy. Today tephen,

9, is unable to walk, talk or feed him elf. Caro l i ne, meanwh i le, i s an

active, heal thy 4-year-old. Genetic te ting, say Jana, "gives Caro­

line the future that Stephen didn't gel to have." ( Kalb, 2006, p. 52)

A h i d d e n ge n et i c d i s o rder robbed Jana a n d Tom M o n a o'

fi rst ch i l d o t a n o r m a l , healthy l i fe. Their e cond c h i l d w a s

pared Lhe

a m e fate b y

advances i n ge n et i c test i n g,

w h i c h gave the M o n acos a

c h a n ce l o i n lerve n e before t h e

...--d a m a ge v. a s d o n e. T h e y were

a b l t: to \ !O p Caro l i n e' i n h er i t ed

d i -,o rd e r fro m d o i n g 1 h e sa m e

d a m age b , co n t ro l l i n g aspec t s

o f h e r e n , i rn n m en t .

• \,\f1iat is o u r basic ge11et ic e11do w111e11t, a ml h o w rt1 11

lz 11mrrn de 1 1elopme111 go ojf t rack?

• How clo t/1e C!lll·iro11 111cnl mid ge11et ics work /o�t•lhcr to

del er111 i rie h u m a n cl1t1 rnctl!rist ics?

CHAP�E R OUTLI N E

Multiple Births: Two-or More-For

the Genelic Pnce of One

Inherited and Genetic Disorders:

When Development Goes Awry

Prologue: Th e F11 1 11 re Is No w

The Basics of Genetics. The M1x1ng

and Matching of Traits

Genetic Counseling: Predicting the

Future From t1,e Genes of the

Present

L o o k i ng A h ea d

Etuliest Develop ment

Genes and Chromosomes·

n,e: Gode o Lil&

44

I n t h i s ch,, p l cr, wt· ' I I t·xa m i n t• 1\' 1 1 ,1 1 d t• ,·d o p m c n l a l

resea rc h e r '> a n d o t h c r ,t·i e n l i !-> h h a vc k.1 r 1 1 nl a hu u t 1,·.1 �· , 1 h a t

h e red i t y a n d t h e t· 1w i ro n m e 1 1 1 w o r k i n 1 ,1 1 1 <l c 1 1 1 t o c r ...·,1 1 1.: .1 1 1 d

� h a pc h u m a n b e i n g, . \\'c beg i n \\' i t h l h c ba !, i c ., o f' h e rcd i t ) , t h e

gcn c t ic t r a n ., m i !, '> i o n o f ch a rac t c r i ... 1 i c ., fro m h i o l o g i t a l p a rc n h

I < > t h e i r ch i l d re n , by ex a m i n i n g h o \\' w c rccc i \ c o u r !..:''- J l l' l it

e n d o w m e n t . We co n , i d c r beh a v i o ra l gcnt·t i ·,, an a rl',1 of '>t u J �·

t h a t ,pcci a l i7cs i n t h e co n ,cq u e n ccs o f h l' rcd i t y 0 11 lwh ,I \ i o r. \\'c

a l so d i'>C LI � , w h a t h a p pc n !, w h e n gcn c t i c fa t.:1 o r-, ca u ., ,._. d c \·d o p ­

m e n t t o go ,n,· r�·, a n d h o w '>llch p ro b l c m '> a rc d ca l 1 1, i t h t h n , u g h

ge n e t i c coL1 11 ,c: l i 11 g .i n d gt· n c t h era p y.

B u t gc n c '> a rc o n l y 0 1 1 c pa rt o f t h e , t o r y o f p re 1 1 a l ,1 I ti c , d n p ­

m c n t . We a l ,o c o n s i d e r t h e wa y:- i n w h i d 1 a c h i l d \ gc n c l i l' h e r­

i t a ge i 11 1 crac 1 w i t h h e r e n v i ro n m e n t : I n o t h e r wo rd , , h o " o n c\

fo m i l y, '>oc i occo n o m ic � l n l u �, a n d J i fl' t' \'Cl l h ca n a ffec1 .1 ,·a r i l' l y

o f c h a ra c t e r i s t i c!,, i n c l u d i n g p hy -. i c a l t ra i h, i 11 1 c l l i gt· tKt' , ,1 11 d

even pcr!,ona I i t y.

h n a l l y, we foc.:t1 , o n t h e ver y fi rq , t age o f d • n· l o p 111 c n l ,

t rac i n g p rc n a l a l g ro \\• t h a n d drn n gc. \Ve n· , i c \\· <,lJflll' o f t h e

a l t e rn a t i ve:,, ava i l a b l e l o o u p l e:-, w h 1 1 fi n d i t d i ffi c u l 1 t o co 1 1 1: ...· i v c .

\\I� a l �o t a l k ,1 b o u 1 t h e � t a �c� o r 1 h c p n• m1 1 a l p e r i o d ,1 11d l w w t h e

p ren a t a l env i ro n m e n t ffl'r<, bot h 1 h r ·a l '> t o-a n d t h e p ro m i se

of-fu t u re g ro w 1 h .

A ft e r read i n g t h i � c h a p t e r, ycrn w i l l b c a h l c t o a 1 h \1·c r t l H::-.c

q uc:.t i o n s:

Transmission of Genetic Information

The Human Genome and Behavioral

Geneltcs· Cracking the Genetic

Code

Review

The I n te rc;tctio n

of H erec;(. i t� ctnd

E nvironmeVL t

FROM R E SE A R C H T O PRACTICE:

Are "Designer Babies" in O u r Future?

The Role of the Env1ronm nt

1n Deter1111111ng the Expression

of Genes. From Genotypes lo

Phenotypes

Studying Development: How Mucl1

Is Nature? How Much Is Nurture?

Pl,ysical Trails: Family

Resemblances

Intelligence: More Research. More

Controversy

Genetic and Environmental

Influences on Personality· Born to

B Outgoing?

DEVELOPMENTAL D IVERSITY:

Cultural Differences in Physical Arousal:

Might a Cullure's Philosophical Outlook Be

Determined by Genet ics?

Psychological Disorders: The Role of

Genetics and Environment

Can Genes Influence ll1e

Environment?

Review

Pre vtettet l G row th

etncl C h et n !!.J e

Fertilization: The Moment of

Conception

The Stages of the Prenatal Penod:

Tlie Onset of Development

Pregnancy Problems

Tl1e Prenatal Environmem. Threats

to Development

B E CO M I N G AN I N FO R M ED CONSU M E R

OF D EVELOPM ENT:

Optimizing the Prenatal Environment

Review

T H E CASE OF. . . The Genetic Finger

of Fate

L o o k i 11g BMk

Ep ilog ut!

Key Tc: r111 s n 1 1rl

0 1 1 n• p ts

45

Gametes The sex cells from

the mother and father that form a

new cell at conception

Zygote The new cell formed

by the process of ferti lization

Genes The basic u n it of

genetic information

DNA (deoxyribonucleic acid}

molecules The substance that

genes are composed of that

determines the nature of every cell

in the body and how it will function

C h ro m o s o m e s Rod-shaped

portions of ONA that are

organ ized in 23 pairs

M o n ozygoti c tw i ns Twins

who a re genetically identical

We humans be gin the course of our lives simply.

Like individuals from tens of thousands of other species,

we start as a single cell, a tiny speck probably weigh i n g no

more than 1 /2 0 -milJionth of an ounce. But from this h u m ble

beginning, in relatively few months, a l iving, bre ath i ng,

un ique infant is born. This fi rst cell is created when a mal e

reproductive cell , a sperm, pushes thro u gh the membrane of

the ovum, the female reproductive cell. .T hese g� as the

male and fem le._rep.w ductiv-e c:ells are als

,vn each con ­

tain huge amounts o enetic i n form ation . About an �r o r

s o aft e r the sperm enters the ov um, the two gametes suddenly

fuse becomi g_one-Gellra-zr.gore: The resulti ng combinat io n

of their genetic instructions-ove r 2 billi o n chemical ly coded

messages-is sufficient to begin crea ti n g a whole person .

pcc i fic ge nes in p rec ise l oca t i o n s o n the ·h a i n o f chro­

mo o m es determ i n e the n a t u re and fu n c t i o n 1 f c,·cr r el l in

the body. Fo r in l a n ce, ge nes detcrm i n l' w h i c h ·l'I I \\· i l l u l t i ­

m a t e l } b c me pa r t o f t h e h ea r t a n d wh ich \\" i l l become part

of t h e mu cles of th leg. G e n es a lso l':-t a b l i :, h how d i fferent

pa r t of t h e body w i l l fu n c t i o n : h m ra i I I }' t h l' heart ,, ill

beat, o r how m uch s t rength a m u ·ell' , i l l h a ve.

If each pare n t prov ides j ust 23 c h rn rn o ·n m cs, ,, here

doe t h e poten t i a l for t h e vast d i ve rs i t y or h u ma n being

come fro m ? The a n swer resi des p r i m a r i l y i n t h e n a t u re of

the p rocesses t h a t u n derl ie t h e ce l l d i v i s i o n or t h e gametes.

v\fhen t h e sperm a n d ova a re formed in t h e ad u l t h u man

body in a pro cess ca l l ed meiosis, each ga m e t e rece ives one of

the two chromoso mes that m a ke u 1 each o r t l1l· 23 pa irs.

Beca u e for each o f t h e 23 pa i rs i t i s la rge!} a m a t ter of

cha nce which m e m ber o f the pa i r is co n t r i h u t l·d, t he re are

2- 3 , or about 8 m i l l ion com b i na t ions poss i ble. Fu r t h ermore,

other p roccsse , such as random t ra n s fo r m a t i o ns or pa r t icu­

lar genes, acid to the va r i abi l i t y o f the gen e t i c brew. The u l t i ­

m a t e ou tcome: tens o f t rillio11s of poss i b l e genetic

com b i nations.

With so many poss i b l e ge n e t i c m i x t u res p rovi ded by

hered i t y, there is no l i kel i h ood t h a t someday yo u' l l b u m p

i n t o a ge n e t i c d u p l i ca te of you rse l f-w i t h o n e excep t io n : an

identical t w i n .

Genes and Chromoso m es:

The Code of Life

M u lt i p l e Bi rths: Two-o r M o re­

Fo r the Genetic Price of O n e

• Wh ich human cha racterist ics are sig11 ificr111 t ly

influenced by heredity?

• What happens during the prenatal stages of

development?

• What are the th reats to the fetal e11 viro n 111e11l, and

what can be done about them?

Earliest Develop ment

Th e blueprin ts for creating a perso n are stored and com m u ­

n i c ated in o u r genes, the basic un i ts of genetic i n formati on.

T he rough ly 25, 000 h uma n genes are the b io­

logical equiva l ent of "softw are" that program s

70,000-1 00, 000 Genes

c.

e d eve I opmen t of all parts of t h e

-- t h e 1utur

body's "hardwa re."

Al l genes are com posed of speci fi c

nces of DNA ( deoxyr ibonuc leic acid)

seque

=

4 6 Chrom osomes

molecules. The genes a re arranged i n specific

locatio ns and in a spec ific o rder along 46

ch romo somes, rod-sh aped portions of DNA

=

23 Chromos ome Pairs

t hat are organized in 23 pairs. O nly sex cel ls­

the ova and the sperm-con tain half this

n u m ber, so that a child's mother and father

each provide one of the two ch rom osomes i n

One Hum an Cell

each o f t h e 2 3 pai rs. T h 4 6 c h romosomes

( i n 23 p a i rs ) i n the new zygote co n tain the

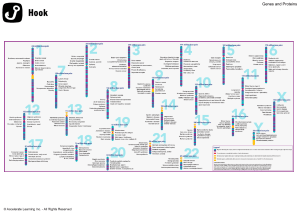

FIGURE 3- 1

gen e tic bl uep r i n t that wi l l guide cel l activity

for t he rest of t h e i n divid u a l 's l i fe ( Pe n n isi,

The Content s of a

I n ternational

S i n g l e Huma n C e l l

Human

2000;

Genome

uencing

Consort

i

u

m

,

200

1

;

see

Seq

Figu

re 3- 1 ).

At the momen t of

a

process

ca

l

Thro

l

ed

ugh

m

itosis,

which

conception, hu mans receive

for

the

repl

ica

t

acco

i

o

n

of

unts

of

most

types

70,000 to 1 00, 000 genes,

cel l s, nea rly a l l the cel l s of the body will con ­

contained on 4 6

chromosomes in 23 pairs.

tai n the same 4 6 ch romosom es a s t h e zygote.

46

D i zyg ot i c twi n s Twins who

are produced when two separate

ova are fert i l i zed by two separate

s perm at roughly the same time

PA RT O N E

Beg i n n i n g s

A l tho ugh it doesn't seem surpri i n g when d o g s a n d cat s g ive

birth to severa l offspring at one t i m e, i n h u ma ns, m ul t i p l e

b i rths a re cause fo r co m m en t . And t hey s h o u l d be: Less t h an

3% of a l l pregnancies p ro d u ce twi ns, a n d the o I ds a re eve n

sl i m mer for t h ree or more c h i l d re n .

Why do m u ltip le b i rths occ ur? S o m e occu r w h e n a c l us­

ter of cel ls i n th e ov u m spl i ts off with i n t h e fi rs t 2 weeks a fte r

fertilization. The res u l t i s two gen et i cal l y i d en t i cal zyg otes,

which a re called 111onozygotic beca use they co m e fro m th e

same original zygot e. Monozygotic t w i n a re tw i n s wh o are

genet ica l l y identica l . Any d i fferences 10 thei r fu t u re deve l op­

ment ca n be attributed o n l y to env i ro n me n t a l facto rs,

because genetically they a re exactly t h e sa me.

There is a secon d , a n d act ual l y m o re co m mo n , mec ha­

n ism that p rod uces m u l t i ple b i rths. In t hese case , t wo se p a­

rate ova are fert i l ized by two separate sperm a t ro u g h l y t he

same t i me. Tw i n s prod uced in t h i s fash i o n a rc k n ow n as

d i zygot i c t w i ns. Beca use they a re t h e res u l t of t wo separ a te

ovu m-sperm com b i nations, the y a re no more g e n et ical ly

s i m i l a r than t wo s i b l i n gs born a t d i ffere n t t i mes.

Of co u rse, n o t all m u l t i ple bi r t h s prod u ce o n l y t wo

babie . Tr i plets, q uadru plets, and even m o re b i r t h s a re pro ­

d uced by e i t h e r ( o r bo t h ) o f the m echa n i s m s t h at yield

twi ns. Thus, t r i plets may be some co m b i n at i o n of rn o n oz)1 got i , d i zygotic, o r t r izygo t i c .

A l t hough the chances of hav i ng a m u l t i p l e birth are typ­

ically sl i m , the odd rise con iderably when couples use fer­

t i l i t y d rugs lo i m p rove the probability of conceiving a child.

For exam ple, I in IO couple u ing fer t i l ity d ru gs have

d i zygotic twi ns, compared to an overal l figure of I in 86 for

a ucasian co u ples in the U n i ted tates. Older \\ Omen, too,

a rc more l ikely to have multiple birt hs, and multiple bi rths

arc also more co mmon in s me familie than they are in oth­

ers. The i ncreased use o f fe r t i l i t y d ru gs and rising average

age of m o t h ers g i v i n g b i rt h has mea n t that m u l t i p l e births

h ave i n c reased i n t h e last 25 yea rs ( see Figure 3 - 2 ; M a rt i n

c t a l . , 2005 ) .

There a rc also racial, ethn ic, a n d nat ional differences in

the ra te of m u l t i ple bi rths; this is probably due to inher ited

d i fferences in the l ikel i hood that more than one o, um will

be released at a time. One out of 70 frica n American cou­

ples have di zygotic birth , compared with the I out of 86 fig­

ure fo r \ 'h i te American couples ( Va ughan , McKay, &

Beh rman, I 979 ; \1\lood, 1 997 ) .

Mot hc.:rs carr y i n g mult iple children run a hi g her than

average risk of prem a t u re delivery and birth co mplications.

onsc q u e n t ly, these mothers must be particul a rl y concerned

abo u t t hei r p renatnl ca re.

"'

t'.

iii

40

30

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .................... . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . ..... .

0

0

0

aia.

"'C:

J

1 98 0

1 985

1 990

1 995

2000

2001

2002

2003

2001

2002

2003

Yea r

...

QJ

a. V,

QJ .c.

... ·t'.

-

200

1 50

. . ...... . . . ............. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

0

:? �

... 0

0 0

QJ 0

QJ 0

..c �

1 9 80

1 98 5

1 99 0

1 995

2000

Year

F I G U R E 3 - 2 R i s i n g M u ltiples

Multiple births have increased significantly over the last 25 years.

What are some of the reasons for this phenomenon?

(Source: Martin et al. . 2005)

Monozyg otic and dizygotic twins present opportu nities to learn about the relative

contributions of hered ity and situational factors. What kinds of things can

psychologists learn from studyi ng tw ins?

Bo y or Girl? Establishin g the Sex of the Child Recall

that there are 23 matched pairs of chromo ome . In 22 of these

pairs, each chromosome is imi. l ar to the other member of its

pair. The one exception is the 23rd pair, which is the one that

determine the sex of the child . ln females, the

23rd pair consi ts of two match i ng, relatively

large X-shaped chromosomes. appropriately

identified as XX. ln males, on the other hand,

the members of the p air are dissimilar. One

consists of an X-shaped chromosome , but the

other is a shorter, smaller Y-shaped chr m

s me. This pair is identified as }..'Y.

A we discussed earlier, each g amete

carrie one chromosome fro m each� of the

parent's 23 pairs of chromosome . Be au a

female's 23rd pair of chromosomes are both

Xs, an ovu m will always carry an X chromo­

some, no matter 1,-v hich chroma ·ome of the

23rd pair it get . A male' 23rd p air is , Y, -o

each sperm could carry eith r ·rn X o r a Y

c h romosome

I f the sperm con t ributes a n X ch ro m o­

some when it meets an o u m ( which,

re member, will always co n t r i b u te a n X

.,

c h romosom e ) , the child w i l l have a n X "'\:

Not only is the X chromosome

pa i r i n g on the 23rd chro mosoml:' and w i l l important in determining

b e a female. l f t h e sp erm o n t ribute a Y gender. but it is also the site of

ch ro mosome. the res ult will b an XY pai r ­ genes controlling other

ing a n d will be a male ( see Fi gure 3 - 3 ) .

aspects of development.

C vt. CI Jt) ter 3

The Start of Life: Genetics and Prenatal Development

47

Dominant trait The one trait

that i s expressed when two

compet i n g traits are present

Recessive tra it A trait within

an organism that is present, but

is not expressed

G e n oty p e The u n d e rlyi n g

c o m b in a t i o n of g e n e t ic materi a l

present (but n o t outward l y

v i s i b l e) i n an o rg anism

It is clear from this process that the

father's sperm determi11es the gender of the

child. This fact is leading to the development

of techniques that will allow parents to

increase the chances of specifying the gen ­

der of their child. In one new tecl1 11 ique,

lasers measure the DNA in sperm. By dis­

carding sp e rm that harbor the w1wanted sex

chromosome, the chances of having a child

of the desired sex increase dramatically

(Belkin, 1 999; Van Balen, 2005 ) .

O f course, procedures fo r choosing a

child's sex raise ethical and practical issues.

For example, in cultures that value one

gender over the other, might there be a

kind of gender discrim ination prior to

birth? Furthermore, a shortage of children

of the less preferred sex might ultimately

emerge. Many questions remain, then,

before sex selection becomes routine

( Sharma, 2008) .

The Basics of Genetics:

The M ixing and Matc h i n g

of Traits

What determined the color of your hair?

Why are you tall or short? What made you

susceptible to hay fever? And why do you

have so many freckles? To answer these

When an ovum and sperm meet at

the moment of fertilizati o n , the

questions, we need to consider the basic

ovum is certa in to provid e an X

mechan i sms involved in the way that the

chromosome, wh ereas the sperm

genes we i nherit from our parents trans­

will provide either an X or a Y

mit information.

chromoso me. Jf the sperm

Vie can start by examining the discov­

contributes its X chromosom e , the

eries of an Austrian monk, Gregor Mendel,

child will have an XX pairi ng on the

in the mid- l 800s. In a series of simple yet

23rd c h ro mosome and will be a girl .

convincing experiments, Mendel cross­

If the sperm contributes a Y

pollinated pea plants that always produced

chromosome, the resu lt will be an

yellow seeds with pea plants that always

XY pairing a n d will be a boy. Does

produced green seeds. The result was not,

this mean that g i rls a re more l i kely

as one might guess, a plant with a combi ­

to be conceived than are boys?

nation of yellow a n d green seeds. Instead,

all of the resulting plants had yellow seeds. At first it appeared

that the green-seeded plants had had no influence.

However, addi tional research on Mendel 's part proved

th is was n ot t r u e . He b red toge t h e r p la n t s fro m t h e n ew,

ye l l ow- seeded gen e r a t i o n that had res u l ted from h i s

o r i g i n a l cross - b reed i n g of the gre e n - seeded and ye llow­

seeded plants. The consistent result was a ratio of th ree­

fourths yel l ow seeds to one- fo u rth green seeds.

Why did th is 3-to-l ratio of yel low to green seeds appear

so consi stently? ft was Mendel's gen i us to provide an a nswer.

Based on h i s experiments w i th pea plan ts, he argued that

48

PA RT O N E

B eg i n n i ngs

P h e n otyp e An observable

t rai t : the trait that actually is seen

H o m ozyg ous I n heri t i n g fro m

parents s i m ilar genes for a given

trait

H eterozygous Inheriting from

parents d ifferent forms of a gene

for a given trait

genes fro m each p a re n t . I f the child receives similar genes, he

is said to be h o m ozygous for the trait. On the other h a n d , i f

t h e ch i l d receives d i ffere n t forms of t h e gene from h i s par­

ents, he is sa i d to be heterozygous. I n the case of heterozy­

gous alleles ( 13b ) , the d o m i n a n t characteristic, b rown eyes, is

exp ressed . However, if the child happens to receive a reces­

sive allele from each o f his paren ts, and therefore lacks a

dom i n a n t cha racteristic ( bb ) , he ,, ill display the recessive

characterist ic, such as blue eyes.

Trans m i s s i o n of G e n eti c I nfo rmation

Gregor Mendel's pio neeri ng experiments o n

pea p l a n t s provided t h e fou n d ation for the

study of genetics.

wh en two com pet ing t ra i ts, such as a g reen or yel lo w c olor ­

ing o f se eds, were both p rese n t , o n l y o n e co u ld b e e x pre ssed

( di splayed) . The one that was exp ressed was ca l l ed a

dom i n a n t tr a i t . Meanwh ile, t h e o t h e r t ra i t rem a i n e d p res ­

e n t i n the orga n i s m , a l though n o t exp ressed . Th i s was

called a rec essiv e t ra i t . In the case of M e n d e l ' s o rig i n a l pea

pla nts, t he offsprin g p l a n ts received gen etic i n form ation

fro m bot h the gree n - seed ed a n d t h e yel l ow-seede d pa re n ts.

However, th e yellow trait was d o m i n a n t , a n d conseq ue n tly

the recessive green t ra i t d i d not asse r t itself.

Ke e p i n mi nd, ho we v er, that genet ic material rela t i ng t ?

bot h pare nt plants is present i n the o ffs p r i n g, even th o ugh it

cannot be seen . The genetic i n formatio n is kno w n as the

� rga n i s m's genotype . A genotype is the underlying comb i n a­

tion of genet ic material p resent ( but outwardl y i n visib le) in a n

or� ani sm. I n contrast, a phenotype is t h e o bservable tra i t , the

tr ait that actu ally is seen. Al though th e offspri n g of the yel low­

seede d an d green-seeded pea plants all h ave yel l o w see ds ( i.e . ,

th ey h ave a yell ow-seeded phenotype ) , the ge notyp e consis ts

of ge netic i n formation relating to both paren ts.

And wha t is the nature of the i n fo rmat i o n in t he geno ­

ty pe? To answer that question, let's turn fro m peas to people .

I n fact, the princi ples are the sa me not only fo r pla nts and

human s but also for the majorit y of spec i es.

Recall that parents transmit genetic i n formatio n to thei r

offspring v i a t h e chromosomes they co n t r i b u te t h ro ugh the

gam ete they provide d u ring fer t i l i za t i o n . Some o f t h e genes

form pai rs called alleles, ge nes govern i ng traits t h a t may take

alternate forms, such as h a i r or eye color. Fo r exa m ple,

b rown eye color is a dom inan t t ra i t ( R ) ; b l u e eyes a re reces­

sive ( b ) . A ch i ld 's a l l e l e may conta i n s i m i l a r o r d i ss i m i l ar

We c a n see t h i s p rocess at work in h u m ans by considering

the t ransmission of pl1c11ylketo 1 1 1 1 ria (PKU) , an inherited dis­

order in which a child is unable to make use o f phenylala­

n i ne, an esse n t i a l a m i n o acid p resent in proteins found in

m i l k and other foods. If left untreated, PKU allows phe­

nylal a n i n e to build up to toxic levels, causing brain damage

and mental retardat i o n .

PKU is p rod uced b y a si ngle allele, or p a i r of genes. As

show n in Figure 3-4, we can label each gene of the pair with

a P if it carries a d o m i n a n t gene, which causes the normal

production of phenylala n i ne, or a p if it carries the recessive

gene that p ro d u ces PKU. In cases in which neither parent is a

P K U ca rrier, both the mother's and the father's pairs of

genes are the domi nant form, symbolized as PP. Conse­

quently, no matter wh ich member of the pa i r is cont ributed

by the mother and father, the resulting pair of genes in the

child will be PP, a n d the child will not have PKU.

However, consider what happens if one of the parents

has a recessive p gene. In this case , whi ch we can we symbol­

i ze as Pp, the parent will not have PKU, because the normal P

ge ne is dominant. But the recessive gene can be passed down

to the child. This is not so bad : If the child has only one reces­

sive gene, it will not suffer from PKU. But what if both par­

en ts carry a recessive p gene? In this case, although neither

parent has the disorder, it is po ssible for the child to receive a

recessive gene from both parents. The child's geno type for

PK U then will be pp, and he or she will have the disorder.

Rem ember, though, that even children whose parents

both have the recess ive gene for PKU have only a 25%

chance of inheriting the disorder. Due to the laws of proba­

bility, 25% of ch ildren with Pp parents will receive the dom­

i n ant gene from each parent (these children's genotype

would be PP) , and 50% will receive the dominant gene fro m

one parent and the recessive gene from the other ( their

geno types wo uld be e ither Pp or pP) . Only the unlucky 25%

wh o receive the recessive gene from each parent and have the

genotype pp will suffer fr o m PKU.

Polyg enic Traits The transmission of PKU is a good way

to ill ust ra te the basic princi p les of how genetic i nformation

passes from parent to child, altho ugh the case o f PKU is sim­

pler than most cases of ge netic transm ission. Relativel y few

traits are governed by a si ngle p air of genes. I nstead, most

Normal

Carries recessive Ca rries recess ive

PKU gene

PKU gene

Ca rrier

C a r r i e r Affl i cted

with P K U

R e s u l t : One in f o u r ch i l d ren w i l l i n herit two

d o m i na nt genes a n d w i l l not have P K U ; two

in fou r w i l l i n h e rit one recessive gene and not

be affl icted with P K U but w i l l carry the

recessive gene: a n d o n e i n four will have P K U

F I G U R E 3-4 PKU Probabi l ities

PKU, a d isease that causes brai n damage and mental retardation, is pro d u ced by a

single pair of genes inherited from o ne's mother and father. If neither parent carries

a gene for the disease (a), a child can not develop PKU . Even if o n e parent carries

the recessive gene, but the other doesn 't (b), the c h i ld cannot i nherit the disease.

However, if both parents carry the recessive gene (c), there is a one i n fou r c h ance

that the child will have P K U .

Ch/;l,l'.)ter 3

The Start of Life : Genetics and P renatal Development

49

Polygenic inheritan ce

Inheritance in whi ch a

combi nation of multiple gene

pairs is respo nsible for the

production of a particular trait

X- lin ked genes Genes that

are considered recessive and

l ocated only on the X

chromosome

B e ha v i o ra l g e n et i c s

T h e study of t h e effec ts of

heredity on b ehavior

FIGURE 3-5

I n h erit i n g H e m o p h i l i a

Hemoph i l i a , a blood - c lotting disorder.

has been an inherited problem

t h ro u g h o u t the royal families of Europe,

as i l l ustrated by the descendants of

Queen Victoria of Britain .

(Source: Adapted from Kimbal l , 1 983)

traits are the result of polygenic inheritance. In pol yge n ic i n ­

heritance, a combi nation o f multiple ge n e pa i rs is res p o n s i ­

ble for the production o f a particular trait.

Furth erm ore, s o m e genes come in several alternate

forms, a n d still o thers act to modify t h e way that p a r t i c u l a r

genetic traits ( p roduced by other a l l e l e s ) a re disp layed .

Genes also vary i n terms o f t h e i r reaction ra nge, the pote n ­

t i a l degree o f variab i l i t y i n the actual express i o n o f a t r a i t

due to environ m e n t a l c o n d i t i o n s . A n d

some traits, such as blood typ e , a re p ro ­

du ced by genes i n wh ich nei ther member

o f a pair o f genes c a n b e class i fi e d as

p u rely d o m i n a n t or recessive . I nstead ,

the t rait i s exp ressed i n ter ms of a c o m b i ­

nation of t h e two genes-s uch a s t y p e A B

blood.

A number o f recessive genes, called X­

linked genes, are located only on the X

ch romosome. Recall that i n females, the

23rd pair of chromosom es is an XX pai r,

whereas in males it is an XY pair. One result

is that m ales have a higher risk for a variety

of X-linked disorders, because males lack a

seco nd X chromosome that can co unteract

the genetic information that prod uces the

Esti mated percentage o f each

disorder. For example, ma les are sign i fi ­

crea ture' s tota l genes fou n d i n

cantly more apt to have red-green color

hum ans are ind icate d by th e

blind ness, a disorder produced by a set of

dotted l i ne .

genes on the X chromosome .

FIGURE 3-6

S i m i l arly,

the

blood

d i s o rd e r

U n i q uel y H u m a n ?

hemoph ilia i s p ro d u ced by X - l i n ked

H umans h ave about 2 5 , 000

ge n e s . H e m o p h i l i a h a s been a rec u r re n t

gene s, m aking them n ot muc h

p ro b l em i n t h e roy a l fa m i l i es o f E u ro p e ,

more genetic ally complex than

a s i l l u s t r a t e d i n F i g u re 3 - 5 , w h i ch s h ows

some prim itive specie s.

t h e i n h e r i ta n ce o f h e m o p h i l i a in the

(Source: Cetera Genomics :

desc

e n d a n t s o f Q u ee n V i c t o r i a of G r e a t

International Human Genome

Sequencing Consorti u m . 2001 )

B r i ta i n .

50

PART O N E

Beg i n n i n gs

The H u m an G e n o m e and B e h avi oral

Gen etics : C rac k i n g the Gene t i c Cod e

Men d e l 's a c h i eve m e n t s i n recog n i z i n g t h e ba s i c s o f g e n et i c

t r a n s m i ssio n o f t ra i t s were t ra i l b l a z i n g . H owe v e r, t h ey m a r k

o n l y th e begi n n i n g o f o u r u n d e r s t a n d i n g o f t h e w a y s t h ose

pa rt i c u l a r s o rt s of c h a r a c t e r i s t i c s a rc passed on fro m o n e

gen era t i o n to th e next. Th e most recen t m i l e st o n e i n u n d er­

sta nd i ng ge n et i c s was re a c h e d i n ea r l y 200 I , w h e n m o l ec u la r_

ge n e t i cists s u cc eede d i n m a p p i n g t h e s p ec i fi c seq u e n ce o t

ge nes o n eac h c h ro mosome. Th i s acco m p l i s h m e n t sta n ds as

? n e of t h e mo st i m po r ta n t m o m e n t s i n t h e h i s t o r y of genet­

JCS, a n d , fo r t h a t m a t t e r, all o f b i o l ogy ( I n t e rn a t i o n a l H u m an

Geno m e Seq u e n c i n g Co n so rt i u m , 200 1 ) .

Al rea dy, t he mappi ng o f the gene seq uence has pro vid ed

impo rtant a dvan ces in o u r u n derstand i ng of genet ics. Fo r

i n s tan c e, the n u mber of h u m a n ge n es, long though t to be

1 00, 00 0, has be en revi sed downwa rd to 2 5 ,000- not m any

� ore than is found i n organisms that a re fa r l ess co m p l ex ( s ee

Fi gu re 3 - 6 ) . Fur the rmore, scientists h ave d iscovered t ha t 99 . 9%

of the gene s equ ence is shared by a l l h u m ans. I n sho rt, t his

means that we humans a re far m o re s i m i l ar to o ne a not her th a n

we are d i fferen t . It also indicates that m a ny of the d i ffe ren ces

that see m i ngly separate peopl e-such as race-a re , l iter a lly,

o nl y. ski n d e ep . Human genome m a p p i n g w i l l al so help iden t i fy

particula r d iso rders to wh ich a give n i n d i v i d ual is s u scep ti ble

( Gee, 2004; Delisi & Fleisch haker, 2007; Gupta & State, 2 007) .

The m a p p i n g of t h e h u m a n gen e s e q u ence i s s u p p o r t i n g

the fi e l d of behavio ral gen e t i cs. A s t h e n a m e i m p l i es ,

behavi oral genetic s stud ies the effects o f h e red i t y o n psy­

chologica l c h a racteristic s. R a t h e r t h a n s i m p l y exa m i n e sta ­

b l e , u n c h a n g i n g characte ristics su c h as h a i r o r e ye col o r,

behav i o r a l ge net icists take a b ro ader a p proach a n d con s i d e r

h o w o u r pers o n a l i t y a n d behav i o r a l h a b i t s a re a ffect ed b y

ge netic factors. Perso nal ity tra i ts s uch as s h yness o r sociabi l i t y,

mood i n ss a n d assertiveness a re a m o n g t h e a reas b e i n g

s t u d i e d . O t h e r b e h a v i o r a l ge n e t i c i s t s s t u d y p s yc h o l o g i c a l

The Genetic Basis of Sel ected Behavi oral Disorders and Traits

Behavio ral Trait

Current Ideas o f Genetic Basis

H u ntington's disease

Huntington gene has been identified.

Early-onset (fa m i l ial) Alzhei mer's d i sease

Three distinct genes have been id entified .

Frag i l e X mental ret ard ation

Two genes have been identified.

Late-on set Alzheimer's di sease

One set of genes has been associated with increased risk.

Atte nti on -deficit/hyperact ivity d i sorder

Three locations related to the genetics invo lved with the

neurotransmitter dopamine may contribute.

--------

Dyslexia

Relationships to two locations, on chromosomes 6 and 1 5 ,

have been suggested.

Schizophrenia

There is no consensus, but l inks to nume rous chromosomes,

including 1 , 5 , 6 , 1 0 , 1 3 , 1 5 , and 22 have been reported .

(Source:

Adapted from McGullin, Riley, & Plomin, 200 1 )

d i s o rders such a s d e p ressi o n , attention- deficit/hyperac t i vity

d i so rder, a n d sch izoph ren i a , looking fo r poss ibl ge netic

l i n ks ( Baker, Mazzeo, & Kendler, 2007; DeYo u ng, Quilty, &

Pe t e r s o n , 2007; Haeffel et al., 2008; see Ta ble 3 - 1 ) .

The p rom ise o f behavioral ge netics i s substa ntial. For one

t h i ng, resea rchers worki ng within the field are gai n i n g a better

understa n d i n g o f the specifics of the ge netic code t h at u nder­

lie h u m a n behavior and development. Eve n more important,

researchers are seeki ng to i dent i fy how genetic defects may be

remed ied ( P l o m i n & Rutte r, 1 998; Peltonen & McKusick,

200 1 ) . To u n d e rstand how that goal might be reached, we

need to co nsider the ways in which genetic facto rs, which nor­

mally cause develop m ent to p roceed so smoothly, may falter.

Alternat ive ly, certain environmental facto rs, such as

exposure to X- rays o r even to h ighly polluted air, may

uce a malformation of g e netic mater ial ( see Figure 3 - 7 ) .

prod

V

\,hen such dama g ed g enes are p assed o n to a child, the

I n herited and Genetic Disorders:

When Deve l o p ment Goes Awry

P K U is j u st one of several disorders that may be i n herited.

Like a b o m b t h a t i s harm l ess u n t i l its fuse is lit, a recessive

gene res p on s ible for a d iso rder may be passed on unknow­

i n gly f r o m o n e generation to the next, revealing i tself only

when, by cha nce, i t is p a i red with another recessive gene . I t is

only when two recessive genes come toget her l i ke a match

a n d a fuse that the gene w i l l exp ress itself and a child w i l l

i n h e r i t the ge n e t i c disorder.

But t h e re is another reason that genes can be a source of

conce rn : I n so m e cases, genes beco me physically d a m a g ed.

For i n s tance, genes may b reak dow n due to wea r-an d - tea r or

to cha nce eve n ts o c cu r r i ng d ur i n g the cell-division p ro cesses

of meiosis a n d m i tosis. And someti mes, for no known rea­

so n , genes s p o n t a n eously cha nge t h e i r for m , a p rocess called

spontn neous m 1 1 t11tion .

F I G U R E 3- 7 I nhaled Ai r and Genetic M utations

Inhalation of unhealthy, polluted air may lead to mutations in genetic material in sperm .

These mutations may be passed on, damaging the fetus and affecting future generations.

(Source: Based on Samet. DeMarini. & Malling. 2004 . p. 97 1 )

C hlil.11 te r 3

The Start of Life: Genetics and Prenatal Development

Sl

Down syndrome A disorder

produced by the presence of an

extra c h romosome on the 2 1 st

pair; once referred to as

mongolism

Fra g i l e X syndrome

A disorder prod uced by injury to

a gene on the X chromosome,

producing mild to moderate

mental retardation

Sickle- c e l l a ne m i a A blood

d isorder that g ets its name from

the shape of the red blood cells in

those who have it

Tay-Sa chs disease A d i s ord e r

t h a t produces b l i n d ness a n d

m u scle degen eration p r i o r t o

death; there is no treatment

results can be disastrous m terms o f fu t u re p hysical a n d

cogn itive development (Samet, DeMari n i , & M a l l i ng,

2004 ) .

In addition t o P KU, which occurs once i n 1 0 ,000 to

20,000 births, other inheri ted a n d gen etic d isorders i n c l u d e :

• Down syndrome. As w e noted earlier, m o s t people have 4 6

chromosomes, arranged in 23 pairs. O n e exception is i n d i ­

viduals with Down syndrome, a disorqer e.!:od uced b y t h e

presence o f an extra chromosome on t h e 2 1 st a i r. Once re­

ferred to as mongolism';- Down syn rome is the ;;;��re­

quen t cause of mental retardation. It occurs in abo u t 1 o u t

of 5 0 0 births, although the risk i s m uch grea ter i n mothers

who a re unusually yo ung or old ( Crane & Morris, 2006 ) .

• Fragile X syndrome. Fra gile X syndrome occu rs when a

p articular gene is injured o n the X chromosome. The re­

sult is mild to moderate mental retard a t i o n .

• Sickle-cell anemia. Around one-tenth o f t h e African Ameri­

can population carries genes that produce sickle-cell anemia,

and 1 African American i n 400 actually has the djsease. SickJe­

cell anemia is a blood rusorder that gets its name from the

shape of the red blood cells in those who have it. Symptoms

include poor appetite, stunted growth , swollen stomach, and

yellowish eyes. People afflicted with the most severe form of

the disease rarely live beyond childhood. However, for those

�th l � ss severe cases, medical advances have produced signif­

tcant mcreases in life expectancy.

• Tay-Sachs disease. Occurring mainly in Jews of eastern

E � ropean ancestry and in French Canadians, Tay-Sachs

disease usually causes death before its victims reach school

a g_e. There is n o treatment fo r the disorder, which produces

blmdness and muscle degeneration prior to death .

• Klinefelter's syndrome. One male out of every 400 is born

with Klinefelter's syndrome, an abnormality resulting from

the presence of an extra X chromosome. The resulting XXY

complement p roduces underdeveloped genitals, extreme

heigh t, and enlarged breasts. Klinefelter's syndrome is one of

a number of gen eti c abnormalities that result from receiving

the improper number of sex chromosomes. For instance,

K l i nefe lte r's syn d ro m e

A di sorder res u l t i n g from t11e

presence of an extra X

chromosome that produces

underdeveloped genitals,

extreme height, a n d enlarged

breasts

there a re disorders p rod uced b y a n ext ra Y c h ro m osome

( XYY ) , a m issi n g second c h romosome ( ca l l ed Tu rner syn­

drome; XO), and th ree X c h ro m osomes ( X X X ) . Su c h d isor­

ders are typically c h a racterized by p robl e m s rel a 1 i ng to

sexual characterist ics and by i n tellec t u a l defi c i t s ( Ke. ler,

2007; J. Ross, Stefanatos, & Roel tge n , 2007 ) .

J t i s i m porta n t t o keep i n m i n d t h a t t h e m re fa c t a d i s ­

o rd e r has ge n e t i c ro ots d oes n o t m e a n t h a t e nv i ro n m e n t a l

factors do not also play a role ( Mo l d i n & Go t t es m a n , I 997) .

Co nsider, fo r i ns t a n ce, sickl e-cel l a n e m i a , wh ich p r i m a r i l y

a ffl icts people of A fr i c a n desce n t . Because t h e d i se.ise ca n b e

fatal i n ch i l d h ood , we'd ex pect t h a t t h ose w h o s u ffc..: r fro m i t

wo uld be u n l ikely to l i ve long e n o u g h t o p a s s i t o n . A n d t h i s

does seem to be t ru e , a t l east i n t h e U n i ted S t a tes: C o m p a re d

w i t h pa rts of West A fr i c a , the i n c i dence i n t h e U n i t ed S t a t es i s

much l owe r.

B u t why s h o u l d n ' t t h e i n c i d e n c e o f s i c k l e - c e l l a n e m i a

a l s o be grad u a l l y red u ced fo r peo p l e i n We s t A fr i ca ? T h is

q u e s t i o n p roved p u zzl i n g fo r m a ny yea r s , u n t i l s c i e n t i s t s

d e t e r m i n ed t h a t c a r r y i n g t h e s i c k l e - c e l l ge n e ra i ses i m m u ­

n i t y t o m a l a r i a , wh i c h i s a c o m m o n d i sease i n Wes t A fr ica

( A l l i s o n , 1 9 54 ) . T h i s h e i g h te n e d i m m u n i t y m e a n s t h a t

p e o p l e w i t h th e s i c k l e - c e l l gene h a ve a gen e t i c a d va n t a ge

( i n terms o f res i s t a n ce to m a l a r i a ) t h a t o ffs e t s , to s o m e

d eg ree, t h e d i sadva n t age o f b e i n g a c a r r i e r o f t h e s i ck l e ­

c e l l gene.

The lesson o f s i c k l e - c e l l anem i a is t h a t ge n e t i c fa c to rs

are i n te r t w i n ed w i t h e n v i ro n m e n t a l co n s i d e ra t i o n s a n d

c a n ' t be l o oked at i n i so l a t i o n . F u r t h e r m o re , we n eed t o

r e m e m b e r that a l t h o ugh we've been fo c u s i n g o n i n h e r i ted

fac tors t h a t can go aw r y, i n the vast m aj o r i t y o f c a s es t h e

genetic mech a n i s m s w i t h w h i c h we a re endowed wo rk

q u i te wel l . Overall , 95% o f ch i l d re n born in the U n i ted

S t a te s are healthy a n d n o r m a l . For t h e s o m e 2 5 0 ,00 0 wh o

a re bo rn w i th some s o r t o f physical o r m e n t a l d i so rd e r,

a p p ro p r i a t e i n terve n t i o n o ften c a n h e l p t reat a n d , i n so m e

cases, c u re t h e p ro b l em .

Moreover, due to advances i n beh avioral gene t i cs, gen et ic

.

diffic ulties increasingly can be fo recast, anticipated , a nd

plan ned for before a chi l d 's birth, enabling parents to t ake

steps before the child is b orn to red uce the severity of ce r ta i n

geneti c conditions. I n fact, as scientists' kn owledge rega rd i ng

the specifi c locatio n of partic u l a r genes expa nds, p red i c t i on s

of what the genetic fu ture may hold a re beco m i ng i n c reasi n gly

exact, as we d iscuss n ext ( Pl o m i n & Rutter, 1 99 8 ) .

Genetic Cou nsel i n g : P red i cti ng

the Futu re From the Genes

of the Present

Sickle-cell anemia, named for t h e presence of

m isshapen red blood cells, is carried in the genes of

1 in 1 0 African Americans.

52

PA RT O N E

Beg i n n i ngs

If you knew that yo ur mother a nd grand mother h a d d ied of

Hunti ngton's disease-a devastat i n g, a lways fatal i n h erited d is­

order marked by t remors a n d i n tellect ual deterioratio n-to

Genetic c o u n se l i n g

The discipline that focuses on

helpin g peo ple deal with i ssues

relating to inherited d isorders

U ltra s o u n d sonography

A process i n which high­

freq uency sound waves scan the

mother's womb to prod uce an

image of the un born baby,

whose size and shape can then

be assessed

whom could you t u rn t o lea rn your own cha nces of comin g

down w i t h t h e d isease? The best person to seek wo uld be a

genet ic co u nselor, a mt:mber of a fiel d t h at, u n t i l a few dec ad es

ago, was nonexis � cn 1 ., Ge n e � ic co u ns e l in g focuse on hel p i ng

_

people deal w i t h issues rela t 1 ng to i n h eri ted disor er .

Gep e t i c co u n selo rs use a variety of d a ta-i n t h �vo rk.

�or i nst,mce, co u p l es co n te m p l at i ng hav i ng a c h i ld may see '

to dete r m i n e t h e r i sks i nvol ved i n a fu t u re p regriancy. n

such a case, a cou nselor w i l l t a ke a t h o ro ugh fa m i l y h i sto ry,

seek i n g a ny fa m i l i a l i n cide nce of b i rth defects t h a t m i g h t

i n d i c a t e a p a t t e rn o f recess ive o r X - l i n ked ge nes. I n addition ,

th e counsel o r w i l l assess fac t o rs such as the age of the

m o ther a n d fa t h e r and a ny prev io us a b n o r m a l i t i es i n o t h er

c h i l d ren t h ey m a y have a l ready had ( Resta et a l . , 2006 ) .

Ty p i c a l l y, ge n e t i c counselors sugges t a t h o rough physi­

cal exa m i n a t i o n . Such a n exam may i den t i fy physical abnor­

m a l i ties that p o t e n t i a l parents may h ave and n o t be aware of.

I n add i t i o n , s a m ples o f b l o o d , ski n , a n d u r i n e m ay be used to

iso l a te a n d ex a m i n e spec i fic c h ro m oso mes. Possible ge netic

defects, such as t h e p rese nce o f an extra sex c h ro m osome,

Chorionic v i l l u s sampl i n g

(CVS) A test u s e d t o find

genetic defects that involves

taking samples of hairlike

material that su rrou n d s the

embryo

can be identi fied by assem b l i n g a ka ryotype, a chart con­

t a i n i ng e n l a rged photos of each of t h e c h romosomes.

A va r i ety of tech niques can be used

to assess the health o f an unborn child if a woman is al­

ready pregna n t ( see Tab l e 3 - 2 fo r a list of currently avail­

able tests ) . The earliest test is a fi rst- t,·irnester screen , ,,v hich

comb i n es a blood test and u l t rasound sonography in the

I I th to 1 3 th week of pregnancy. In ultrasourul.s_o.n_Qgia­

phy, high-frequency sound waves oo mbard the mother's

womb. These waves p roduce a rather i ndistinct, but use­

ful , image of the u nborn baby, whose size and shape can

then be assessed. Re peated use o f ultraso u n d sonography

can reveal devel opmental patterns. Altho ugh the accura cy

of blood tests and ultraso u n d in iden t ifying abnormal ities

i s not high early in p regnan cy, it becomes m o re accurate

later o n .

A more invasive tes t, chorionic villus sampling

(CVS) , c a n be employed in the 1 1 t h to 13th week if blood

tests and ultrasound have identi fied a potential p roblem .

Prenatal Testi ng

Fetal Development M o n itori ng Tech n i q u es

Technique

Description

A m n iocentesis

Done between the 1 5th and 20th week of pregnan cy, this proced u re examines a sample of the

amniotic fl u i d , which contains fetal cel ls. Recommended if either parent carries Tay- Sach s ,

s p i n a bifida, sickle-cell , Down syndrome, muscu l ar dystrophy, or Rh d i sease .

Chorionic villus sam p l i n g (CVS)

Done at 8 to 1 1 weeks, either transabdominally or transcervical ly, depen d i n g on where the

placenta is located . Involves inserting a need le (abdominally) o r a catheter (cervically) i nto the

su bstance of the placenta but staying outside the amniotic sac and removing 1 O to

1 5 m i l l igrams of tissue. This tissue is manually cleaned of maternal uteri ne tissue and then

grown i n culture, and a karyotype is made, as with amniocentes i s .

Em bryoscopy

Exami nes the embryo or fetus during the fi rst 1 2 weeks of preg nancy by means of a

fiber-optic endoscope inserted through the cervix. Can be performed as early as week 5 .

Access t o the fetal circu lation may be obtai ned through t h e i n strument , a n d d i rect

visualization of the embryo permits the diagnosis of malformations.

Fetal blood sampling (FBS)

Performed after 1 8 weeks of preg nancy by collecting a small amount of blood from the

umbi lical cord for test i n g . Used to detect Down syn d rome and most other c h romosome

abnormalities in the fetuses of coup les who are at increased ris k of having an affected c h i l d .

Many other d iseases c a n be di agnosed using t h i s technique.

Sonoem bryology

Used to detect abnormal ities i n the fi rst trimester of pregnancy. I nvolves h i g h-frequency

transvag i nal probes and dig ital image processing. I n combination with u ltrasound , can detect

more than 80% of all malformations during the second trimester.

Sonogram

Uses ultrasound to produce a visual image of the uterus, fetus, and placenta.

U ltrasound sonography

Uses very h igh-frequency sound waves to detect structural abnormal ities or m u ltiple

preg nancies, measure fetal growth, judge gestational age, and eval u ate uteri n e abnorm alities.

Also used as an adjunct to other proced ures such as amniocentesi s .

The Start of Life: Genet ics and Prenatal Developm ent

53

Amn iocentesis The process

of identifying genetic defects by

exam i n i n g a small samp l e of

fetal cells drawn by a needle

inserted i nto the amniotic fl u i d

surrounding t h e un born fetus

In amn iocentesis, a sample of fetal

cells is withdrawn from the amn iotic

sac and used to identify a number

of ge netic defects.

Th is proced u re i nvolves inserting a

thin needle i n to the fetus a n d

extracting s m a l l samples of hairl i ke

the

material

that

surro u n ds

em bryo. The test can be done

between the 8th and 1 1 th week o f

preg nancy. However, it produces a

risk of m isca rriage of I i n I 00 to l

in 200; because of the r i sk, its use is

relatively i n frequent.

In amniocentesis, a small sample of fetal cells is drawn by

a tiny needle i nserted into the amn iotic fluid surro u n d i n g the

unborn fetus. Carried out 15 to 20 weeks into the pregnancy,

amniocentesis allows the a nalysis of the fetal cell s that can

identify a variety of genetic defects with nearly 1 0 0% accuracy.

In addition, this test can determine the sex of the ch i l d .

Although there is always a da nger t o t h e fetus in an invasive

pro cedure such as amniocentesis, it is generally safe.

After the various tests are complete and all possible i n for­

mation is available, the couple will meet with the genetic

counselor again. Typically, counsel ors avo id giving specific

recommendations. I nstead, they lay out th e facts and present

various options, ranging from doing nothing to taki ng m ore

drastic steps, such as terminating the pregnancy th rough

abortion. Ultimately, it is th e parents who m ust dec ide what

course of acti on to follow.

S c reen i n g fo r Future Prob l e m s The newest role fo r ge­

n e t i c co u n sel ors i n vo lves testing people to i d e n t i fy whether

they th emselves, rath e r t h a n th eir ch i l d re n , are susceptible

to fu t u re d i s o rders because of gen etic a b n o r m ali ties. For

i n stance, H u n t ington's d i sease typ i cally does not appear

until peop le reach t h ei r 40s. However, g e n et i c testing can

i d e n t i fy m uch e a rlier whether a p e rson car ries the fl awed

ge n e t h a t produces H u n t i n gton's d isease. Pres u m a b l y, peo­

p l e's know l e d ge t h a t t h ey ca rry t h e ge ne can help them p re­

p a re t h e m selves fo r t h e fu t u re ( E n s e n a uer, M i chels, &

Re i n ke, 2 0 0 5 ; C i n a & Fell m a n n , 2006 ) .

I n a d d i t i o n t o H u n tingto n's d isease, m o re t h a n 1 , 000

d i sorders can be pred icted o n the basis of ge n e t i c test i n g

( see Ta b l e 3 - 3 ) . A l t h o ugh s u c h test i n g m a y b r i n g wel co m e

re l i ef fr o m fut u re worr i es-i f t h e resu l ts a re n egative­

p o s i t i ve res u l t s may p ro d uce j u s t t h e o p p o s i te effec t . I n

fa c t , ge n e t i c test i n g rai ses d i ffi c u l t p ract i c a l a n d e t h i c a l

q uesti o n s ( Jo h a n n e s, 2 00 3 ; Two m ey, 2006 ) .

54

PA RT O N E

B eg i n n i n g s

Suppose, fo r i n s t a nce,

From

wo m a n who t h o u gh t she w a s

a h e a l t h - c a re

s u s ce p t i b l e to H u n t i n g t o n 's

p ro v i d e r's

d i sease was t e s t e d i n h e r

perspective:

2 0 s a n d fo u n d t h a t s h e

1/1/ ·11 ;1r0 ·I·r · ,, , - ,. , , ' · 11

d i d n o t ca r r y t h e d e fe c ­

[H1(1 pi 11l(J<, 'I I r ii 1j I• •Si l 11 lS

t i ve gene. Obviously, s h e

il lrit SI r w1 1111 f t • ,; SSL(; Oi

wo u l d experience t remen­

\:J r ,lir. C°l llT lc-• · IIT U ' I , 1qi1t II

d o u s rel i e f. But s u p pose

·01 1 101 11 ne� I )( , t,r 11.·1Is , , · o

kl l(l'II , 11 l( ',1( I ,· .i ilf r " ' , ll Od

she fo u n d t h a t she d i d

po. ,•,,t)lr ur;r 1t · i 1 [ 11 1 111ked

carry t h e flawed ge ne a n d

rl1sorclc � 11 1,li · 1 H<Jl1

w a s t h ere fo re go i n g to gel

i l lir y, Jt r r I 11k f ,r

the d i sease. In t h i s case, she

yo, 11 s , ,li?

m ight wel l expe r i e n ce depres­

sion a n d remorse. I n fa c t , some

studies show that I 0% o f people who

find they h ave the fl awed gene that leads to H u n t i ngto n's dis­

ease never recove r fu l ly o n an e m o t i o n a l level ( G roo p m a n ,

1 9 9 8 ; Wa h l i n , 2007 ) .

Clearly, ge n e t i c test i n g i s a co m p l ica ted i ssu e . I t rarely

provides a s i m p l e yes or no a nswer as to w h e t h e r a n i n d i v i d ­

u a l w i l l be s usceptible to a d iso rder. I n stead , t y p i c a l l y i t p res­

ents a ra nge of p robab i l i t i es. I n s o m e cases, the l i kel i h ood of

actually beco m i n g i l l depe n d s o n the type o f e nv i ro n m e n tal

st ressors to which a pers o n i s exposed . Perso n a l d i ffe rences

also affect a given pe rso n's suscep t i b i l i t y to a d i so rd e r ( Pate­

naude, Guttmach er, & Col l i n s, 200 2 ; B o n ke et a l . , 200 5 ) .

A s o u r u n d e rs t a n d i n g o f gen et ics co n t i n ues t o grow,

resea rchers a n d m e d i c a l p ra c t i t i o n e rs h a ve m oved beyo n d

te s t i n g a n d counsel i n g to ac tively wo r k i n g t o c h a n ge flawed

genes. The possi b i l i t ies for ge n e t i c i n terven t i o n a n d m a n i p u ­

l a t i o n increas i ngl y b o rder o n wh a t o n ce w a s sc i e n ce fi c­

t i o n-as we consider in the Fro m Resea rch t o Prnct ice box on

page 5 6 about p re i rn p l a n ta t i o n gen e t i c d i a g n o s i s .

J

. R E V I E W ..J :

Some Cu rrently Available DNA-Based Genetic Tests

Disease

Description

Ad u l t pol ycystic kid ney disease

Kidney failure and l iver d isease

Alpha- 1 -antitrypsin deficiency

Em physema and liver disease

Alzheimer's d i sease

Late-on set variety of senile dementia

Amyotrophic lateral scl erosis (Lou Gehrig's disease)

Progressive motor function loss leading to paralysis and death

Ataxia tel angiectasia

Breast and ovarian cancer (inhe rited)

Progressive brain disorder resulting in loss of m uscle contro l and cancers

Charcot-M arie-Tooth

Congenital adrenal hyperplasia

Cystic fibrosis

Early-onset tumors of breasts and ovaries

Loss of feeling in ends of limbs

Hormone deficiency; ambig uous genitalia and male pseudohermaphrodrtism

Thick mucus acc u m u l ations in lu ngs and chro n i c infections in lungs

and pancreas

Duchenne muscular dystrophy (Becker

muscular dystrophy)

Severe to m i ld muscle wast i ng , deterioratio n , weakness

Dystonia

Factor V-Le iden

M u scle rigidity, repet itive twisting movem ents

Fanconi anemia, gro u p

Fragile X synd rom e

Gaucher d isease

Hemophilia A and B

Hered itary non polyposis colon cancer a

Huntingto n 's disease

Myotonic dystro phy

B lood-clotting disorder

Anemia, leukemia, skeletal deformities

Mental retardation

Enlarged liver and spleen, bone degenerat ion

Bleeding d isorders

Early-onset tumors of colon and someti mes other organs

Prog ressive neurological degeneration, usually beg inning i n m idl ife

Progressive muscle weakness

N e urofi bromatosis, ty pe 1

Multiple benign nervous system tumors that can be disfig u ring: cancers

Phenylkelo n uria

Progressive mental retardation due to missing enzyme; correctable by diet

Prader Wi l l i/An gelman syndromes

Sickle-cell disease

Spinal m uscular atrophy

Blood cel l disorder; chronic pain and infections

Severe, usually lethal p rogressive m u scle-wasting di sorder in children

Spinocerebel lar ataxia, type 1

Tay-Sachs disease

Seizures, paralysis; fatal neurological disease of early child hood

Thalassemias

Anemias

Decreased motor skills, cogn itive impairment, early death

I nvolu ntary muscle movements, reflex disorders, explosive speech

These are susceptibility tests that provide only an estimated risk for developing the disorder.

(Source: Human Genome Project, 2006, http ://www.oml.gov/scl/techresources/H uman_Genome/medicine/genetest.shtml.)

0

1 . The h u m a n gen e t i c cod e , t ra n s m i t ted a t t h e m o m e n t of

conce p t i o n , i s stored 1 11 o u r genes and i s co m posed of

specific seq u e n ces o f ____

V N C l :.l clA\SllV

2. ____ t w i n s a re ge netica l l y i d e n t i c a l a n d c o m e from

the same zygote.

:i 1 1 o � k1. u u o i,\1 :.1 at.\S U V

3 . A ____ i s t h e u n derl y i n g com b i n a t i o n o f ge netic

mate r i a l p rese n t ( b ut o u t wa r d l y i n v i s i b l e ) i n a n o rga n ­

ism, w h i l e a p h e n o t y p e i s the obse r v a b l e t r a i t .

•· To see 1 1 1 0 re re view ,1 1 1 cs t i o 1 1 s, log 0 1 1 t o lvly l >c , ,cfop 1 1 1 c 1 1 1 /_, , /1.

The l nteructio n of H ereditM

und Enviro nme nt

Like many other paren ts, Jared's mother, Leesha, and h is

father, J a m a l , t r ied to figure out which o n e of them their

new baby resembled the most. He seemed to h ave Lee­

sh a's big, wide eyes, and Jamal's genero us smile. As he

grew, Jared grew to resemb l e h i s mother and father eve n

more. H is hai r grew i n with a h a i rl i n e just like Leesh a's,

a n d h i s teet h, when they came, made his s m i le resemble

J amal 's even more. He also seemed to act l ike his par­

ents. For exa mple, he was a charming little baby, always

ready to s m i l e at people who visited the house-i ust

l ike h is fr iendly, jovial dad. He seemed to sleep like his

mom which was lucky because Jamal was an extremely

l ight sleeper who could do with as l i ttle as 4 hours a

night, ,vhereas Leesha l i ked a regu l a r 7 or 8 hours.

Were Jared's ready s m ile and regular slee p i ng habits some­

thing he j u s t l uckily i n h erited fro m h is parents? Or did Tamai

and Leesha provide a happy and stable home that encouraged

Chctp te r 3

The Start of Life: Genetics and Prenatal Development

55

M u ltifa c tori a l tra n s m is s i o n

The determ i n a t i o n of traits by a

combinat i o n of genetic and

environ mental factors in which a

genotype provides a ra nge

within which a phenotype may

be expressed

Tempera ment Patterns of

arousal and emotionality that

represent consistent and

enduring c haracteri stics i n an

i n dividual

From Research to Practice

Are " Designer Babies" i n Our Future?

Adam Nash was born to save h i s older sister Mol ly's l ife-lit­

eral ly. Molly was suffering from a rare d i sorder called Fanconi

ane m ia, w h i c h meant that her bone ma rrow was fai l i n g to

p roduce blood cel l s . This d isease can have devastat ing

effects o n young c h i l d re n , i n c l u d i n g birth defects and certa i n

c ancers. M a n y don't survive to a d u lth ood . M o l ly's best hope

for overcoming this di sease was to grow healthy bone mar­

row by rece i v i n g a transplant of i mmature blood cells from the

p l acenta of a n ewborn s i b l i n g . But not j u st any s i b l i n g wou ld

do-it had to be one with com pati ble cells that wou ld not be

rej ected by Molly 's i m m u n e system. So M olly's parents

turned to a n ew and risky tec h n i q ue that had the potential to

save M o l l y by using cel ls from her u n born broth er.

M o l ly's parents were t h e fi rst to use a genetic scree n i n g tech n i q u e

cal led preimplan ta tion genetic diagnosis (PG D) t o ensure that their

next c h i l d wou l d be free of Fancon i anemia. With PGD, a newly fer­

til ized embryo can be screened for a variety of genetic d iseases

before it is im pl anted in the mother's uterus to d evelop. Doctors fer­

tilized several of M o l l y 's m oth er's eggs with her hu sband's sperm i n

a test tube. They then examined t h e e m b ryos to ensure that they

would only i m p l ant the embryo that PG D revealed to be both genet­

ically healthy a n d a match for M o l ly. When Adam was born 9

months l ater, M o l ly got a new lease on life, too: The trans plant was

a success, and M o l l y was c u red of her d i sease .

Molly's parents were understandably focused on saving their

seriously ill daughter's l ife , but they and their doctors also opened a

controvers ial new ch apter in genetic engi neering involving t h e use

of advan ces i n reproductive medicine t h at give parents a degree of

prenatal control over the traits of their c h i l d re n . Another procedu re

that makes t h i s level of genetic control poss i b l e is germ line therapy,

i n which cells are taken from an embryo and then replaced after t h e

defective genes they contain have b e e n re paire d .

W h i l e P G D and g e r m l i n e therapy h a v e important u s e s i n t h e pre­

vention and treatment of seri ous genetic d i so rders , concerns have

been raised over whether such scientific advances can lead to the

development of "desig ner babies"-infants t h at have been genet i ­

cally man ipu lated to h ave traits t h e i r parents wish for. The q u estion

is whether these procedures can a n d s h o u l d be used not only to

correct u n d es i rable genetic d efects, but also to breed i nfants for

specific pu rposes or to " i m prove" future generat i o n s on a genetic

leve l .

T h e et hical concerns are numero u s : I s i t ri g h t to tailor babies t o

serve a specific p u rpose, however noble? Does t h i s k i n d o f genetic

control pose any dangers to the h u man gene pool? Wou ld unfair

advantages be conferred on the offspring of t h ose who are wealthy or

privileged enough to have access to these p roced ures? (Sheldon &

Wilkinson, 2004).

Designer babies are n ' t with us yet; c u rrently, scientists d o not

u n d erstand enough about the h u man genome to i d e n t i fy the genes

that control most traits, nor are they able to make g e n e t i c mod ifi ca­

tions to control how those traits w i l l be e x p ressed . Moreov er, the

term itself is a bit m i sl ead i n g . For one t h i n g , babies a re n ' t being

genetically engi neered ; PGD merely entails selec t i n g a n e m b ryo that

already has the d esired genetic makeu p . Fo r another t h i n g , i t 's a d if­

fic u l t and expensive proced u re that does not l e n d itself to casual

use. Sti l l , as Adam Nash 's case reve a l s , we are i n c h i n g c l oser to a

day when it is possible for parents to decide what gen es their c h i l ­

d ren w i l l and wi l l not have .

•

How m i g h t Adam feel w h e n h e l earn s t h a t h e was sel e c t e d to

be born i n o rder to s ave h i s si ster?

o

these welco me traits? \,Vh at causes our behavior? Nature o r

nurture? I s behavior produced b y i n h erited, genetic i n fl u ­

ences, or is it triggered by factors in the environment?

The simple answer is: Th ere is n o s i m ple a n swe r.

The Role of the Envi ronment i n

Determ i n i ng the Expression of Genes:

From Genotypes to Phenotypes

As devel opmental research accu m ulates, it i s beco m i n g

increasi ngly clear that t o view b e h av i o r a s due t o either

ge n e t i c or env i r o n m ental factors is i n ap p ro p r i ate. A given

behavi or is not ca used j ust by genetic fa c tors; n o r i s it ca used

sol ely by envi ron m e n tal forces. I n stead , as we fi rs t d i scussed

56

PART O N E

B eg i n n i n g s

How m i g h t the c i rc u m stances of Adam 's b i rt h affect t h e rela­

t i o n s h i p between h i m and M o l l y as t h ey g row u p ?

What if o u r u n derstan d i n g of t h e h u m an g e n o m e develops to

the point t h at it becomes p o s s i b l e to use P G D to control the

fut u re i n t e l l i g e n c e , attracti ve n e s s , or sexual i ty of one's c h i l ­

d ren? Where should we d raw t h e l i ne o n parents' a b i l ity t o d i c ­

t ate what traits t h e i r c h i l d re n w i l l have?

i n Chapter I , the behav i o r is t h e pro d uct o f s o m e co m b i n a ­

t i o n o f the two.

For i n stan ce, c o n s i d e r tempe ra m e n t , p a t t e r n s of a rousal

a nd emo t i o n a l i t y t h a t rep rese n t consi s te n t and e n d u ri n g

cha racte ristics i n a n i n d i v i d u a l . S u p pose w e fo u n d-as

i n c reas i n g evidence sugges t s is t h e c ase-t h a t a s m a l l per ­

centage of ch i l d re n are b o rn w i t h te m pe ra m e n ts t h a t p ro d uce

a n u n u sual degree of p hys i o l o g i c a l rea c t i v i t y. H a v i n g a ten­

dency to s h r i n k fro m a n yth i n g u n u s u a l , s u c h i n fa n t s r eact to

n ovel sti m u l i w i t h a rapid i n crease i n h e a r tbea t and u n usual

e x c i t a b i l i ty o f t h e l i m b i c s y s t e m o f the b ra i n . Such h e i g h t ­

e n ed reac t i v i t y to s t i m u l i a t t h e s t a r t o f l i fe, w h i c h see m s to

be l i n ked to i n h e r i ted facto rs , i s a l so l i ke l y to c a u se c h i l d re n ,

by t h e t i me t h e y a re 4 o r 5 y e a r s o l d , tu be co n s i d e rt?d shy by

t h e i r pa rents a n d tea c h e r s . B u t n o t a l w a y s : S o m e o f t h em

beh ave i nd i s t i n g u i s h a b l y fr o m t h e i r peers a t t h e same age

( Kaga n & S n i d m a n , 1 99 l ; McCrae et al., 2000 ) .

Wh a l m a kes t h e d i fferen c ? T h e an s wer seems t o b e t he

en v i ron m e n t in which the ch il dren a re raised. Children, whose

p a ren ts encourage them to be ou tgo i ng by arran gi n g new

o p p o rt u n i t ies for them, may ove rcom e thei r s hyness . I n co n ­

t rast , ch i l d ren rai sed i n a st ressful env i ro n m ent m arked by

m a r i tal d i sco rd or a prolonged i l l ness may be more l i kely t o

ret a i n the i r shynes later in l i fe ( Ka ga n, A rcus, & S n idman,

1 993; R. Joseph, 1 999; Propper & M oo re, 2006 ) . Jared, des c r i b ed

e·irlier, may have been b o rn with a n easy temperame n t, w h i c h

was rea d i l y rei n forced by his cari n g p arents.

I nte raction of Factors Such fi n d i n gs i llustrate th a t many

t ra i t s refl ect rn u l t i fa ctoriaJ t ra n s , · ion, mea n i n g that they

are determ i 1iecl by .�inat i o n o f b o t h oenetic a n d e nv 1 ro n ­

rfl e rit,il facto rs:- m mu lf i fact orial t ra n sm issi o n , a genotype pro ­

v ides a part icu ,11.--r,1 11ge within \v h ich a p h enot ype ma)' a ch ie ve

exp ressio n . Fo r instance, peopl e wi t h a genotype t h at p e r m i t s

t h e m to ga i n weigh t eas i l y may n eve r be sli m , no mat ter h ow

much t hey diet. They m ay be relatively s l i m , given t h eir ge n et i c

heri tage, b u t they may never be ab l e to get beyo nd a certai n d e ­

gree o f t h i n ness ( Fa i t h , J o h nson , & Allison, 1 997 ) . In many

cases, t h e n , it is the environment that determ i nes the way i n

which a particular ge n o t ype will be expressed as a p he notyp e

( Wachs, 1 99 2 , 1 993, 1 9 96; P l o m i n , 1 9946 ) .

On t h e o t h e r hand, certain genotypes a re relatively unaf­

fected by environmental factors. In such cases, development

fo l l ows a preorda i n ed pattern, relat ively i n depend e n t o f the

spec i fi c env i ro n m en t i n which a perso n is raised. For instan ce,

resea rch on preg n a n t wome n who were severely malnour­

ished d u r i n g fa m i n es caused by World War I I found that the ir

N a t u re

chil d ren were, o n average, unaffected physically or intellectu­

ally as adults (Z. Stei.n et al., 1 975 ). Similarly, no matter h ow

m u ch health food people eat, they are not going to grow

b eyond certain genetically in1posed limitations in height. Lit­

tle Jared's hairline will p robably be affected very little by any

ac t ions on the part of his parents. Ultimately, of course, it is

the u n ique i nteraction of inherited and environ mental factors

that determ ines people's pa tterns of development.

The more a p p ro p r i a te question, then, is how m uch of

the behavior is caused by genetic factors, and how much by

env i ro n m ental factors? ( S ee, fo r exa mple the range of possi­

b i l it ies fo r the determi n a n ts o f in telligence, illust rated i n

Figure 3 - 8 . ) A t one extreme is t h e idea t h a t oppo rtun ities i n

the e nv i ro n me n t are solely responsible fo r intel ligence; o n

the other, that i n telligence is p u r e l y genetic-you either have

it or you don't. The usefulness of such extremes seems to

p o i n t us toward the middle gro u nd-that i ntelligence is

the r e sult o f s o m e comb i n ation of natural mental ability a n d

environmental opportunity.

Studyi ng Development: How M uch

Is Nature? How M uch Is Nurtu re?

Developmental researchers use several st rategies to try to resolve

the question of the degree to which traits, character istics, and

behavior are produced by genetic or environmental factors.

Their studies i nvolve both nonhuman species and humans.

N o n h u m an An i mal Studies: Contro l l ing Both G eneti cs

and Enviro n m ent It is relatively simple to deve lop breeds

of animals that are genetically sim ilar to one another in terms

of spec i fi c traits. The people who raise B utterball turkeys for

----

I n t e l l i g e nce i s prov ided

entirely by genetic fac­

tors; environment pl ays

no ro le. Even a h i ghly

enriched environment

� a n d exce l l ent e d u cation

:fl m a ke no d i fference.

N u rt u re

Although larg e l y

i n h e rited, i ntelligence

is affected by an

extremely en riched or

depr ived enviro n m ent.

.!!:!

.c

'iii

V,

0

CL

I ntel l i gence is affected

both by a person's

genetic e n d owment a n d

envi ronment. A person

geneti cally predisposed

to low intelligence may

perform better if raised

in an enriched e n v i ro n ­

ment o r w o r s e i n a

dep rived environm ent .

S i m i l arly, a person

genetica ll y p red is posed

to h i g her intellig ence

may perform worse i n

a deprived e n v i r o n m e nt

or better i n a n en riched

enviro n m ent.

Altho u g h inte l l igence

is l a rg e l y a result of

enviro n m e nt, g e n etic

a b normalities may

prod uce menta l

retardati o n .

Inte llig ence depends

entirely o n the environ­

m e nt. G e n etics

p l ays no role in

d eterm i n i n g

i ntel l ectual success.

F I G U R E 3 · 8 Poss i b l e Causes of I nte l l igence

Intelligence may be explai ned by a range of differing poss ible sources, spanning the nature-nurture con t i n u u m . Which of tl1ese

explanations do you find most convi ncing, g i ven the evidence discussed i n the chapter?

Ch CI.p te r 3

The Start of Life: Genetics and Prenatal Deve l o pment

57

Thanksgiving do it all the time, producing turkeys that grow

especially rapidly so that they can be b rought to market inex­

pensively. Simil arly, strains of laboratory animals can be bred

to share similar genetic backgrounds.

By observing animals with similar genetic backg rounds

in different environmen ts, scientists can determin e, with

reaso nable precision, the effects of specific kinds of environ­

mental stim ulation. For example, animals can be raised in

unusually stimulating environmen ts, with lots of items to

climb over or th rough , o r they can be raised in relatively bar­