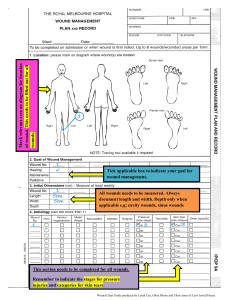

the cells, tissues, and the integumentary system. And this is Unit One, All right. So let's start. I -- I hear this a lot. Why -- why do I need to know all these things? Well, who cares about the cells? You know, nobody can see them. They're microscopic. I don't run a microscope. And then they have all these little organelles, you know, that I need to learn about. I need to learn their functions or what they look like and identify them. Well, it all starts here. And as I'm sure you've heard before, they're essentially the building blocks of us, of humans, of -- of any living creature. And they -- they comprise tissues. You know, we have cells which make up tissues. Tissues make up -- various different types of tissues make up organs. And then you have a number of different organs that make up entire systems. So it is important to understand their function. As nutrition professionals, you know, we're interested in metabolic reactions, the metabolism of foods. We know that the mitochondria are the powerhouses of cells. And even more recently, there's -- I should say the past couple years -- there -- this research has made me particularly happy. They have found that high intensity training, such as hit training, plyometrics, tabata, actually, as you age, will increase the number of mitochondria that you have. And this is believed to, kind of, be, you know, the fountain of youth. You -- if you remember your history lessons, Ponce de Leon was running around Florida looking for the fountain of youth. And it may, in fact, be this high-intensity, short-duration training that rebuilds or increases the number of mitochondria which, before, was thought to be not possible. Even individuals that are well into their 60s or 70s. So as we become -- we gain more knowledge, we understand these mechanisms at a cellular level, the -- the research broadens. And you need to have a basic understanding of that. There's 200 different types of cells. Obviously, I'm not going to list them all for you. And I probably couldn't if you asked me to. So here's just some basics. One of my favorites is the osteocyte. The neurons I think look pretty cool. And, of course, the gametes for reproduction. Red blood cells we'll talk about. And various different types, whether it's skeletal, cardiac, or smooth muscle, have specific functions. And I would encourage you, if you ever get the opportunity, to take a histology class. It's absolutely fascinating! And you will get down to the cellular level of -- and learn what these various tissues look like under the microscope. And it's something that you could even do online. So that's my -that's my plug. It's one of my favorite things, histology. So you have a cell. And in the cell you have these various organelles. We talked about mitochondria. You have Golgi complex, lysosomes. All -- of course, you have a nucleus. That's where all the genetic material is stored. And they all have jobs to do. And those jobs are to -- to promote the activity or the function of the actual cell that they live in. So it -- it is important, you know, to understand the basics, certainly. That's my soapbox for now. There's basically four types of different tissues. We have epithelial tissue which is usually described as a sheet of cells. It covers body structures. So, you know, your skin is certainly considered epithelial tissue. Your glands that produce secretions. Those have various types of epithelial tissue. Connective tissue is defined as a group of cells in a matrix. There's usually a ground substance, fibers that support and bind together tissues and organs. And the one that comes to mind -- again, I'm back to bone. But bone is a connective tissue. And although often people don't recognize -- recognize the fact that bone and lymph are considered connective tissue, too. And instead of having fibers they, of course, have fluid. Muscle tissue I just mentioned consists of skeletal, cardiac, and smooth muscle. Fibers -- we're particularly -- particularly interested in smooth muscle as clinicians because that's what the GI tract is lined with. And certainly there can be problems with nerve innervation to that smooth muscle and -- and individuals will get various complications or disease states associated with that -- with peristalsis that's not functioning correctly. Or, whether it's -- it's propelling the food too quickly through the GI system, or whether there's difficulty in actually moving that food through. And let's see -- the nervous system, of course, contains neurons, neuroglia. And that's, you know, basically how we get messages from one part of the body to the other. So, again, all in your Visible Body platform, but these are kind of basic things that you should understand and be aware of. So in terms of application, I want to talk about pressure ulcers. And why should you care about pressure ulcers? Well, as a clinician, a dietician, or nutrition professional, you will be responsible for assessing patients and a lot of these patients may, in fact, have pressure ulcers. And you will work with nursing to understand the type or the stage of the pressure ulcer, or the type of wound and be responsible for providing medical -- medical nutrition therapy for treatment of that wound. Or to ensure that they have adequate nutrition so that that wound can heal. And I must say, in my career this has certainly come a long way. I now attend a weekly meeting or rounds where the nurses with the advent of the power charting, or the -- remote charting. Everything's done on the computer. They actually take photos of these pressure ulcers or various types of wounds and, on a weekly basis, document them and then they can measure them on the computer and upload them to the clinical chart, the electronic file so that everybody can see them. You know, whether there's a therapist working them -- with them, or whether it's the dietician. And some of the pictures, you need to be aware -- you're getting into the health care field -- are not -- they're -- they're -- some folks find them a bit difficult to look at. They're wounds! When you visit with patients, or you're in that particular setting, they have smells. There's a particular smell -- wound smell. There's a smell for C. diff. There's -- there's smells that you'll become accustomed to or you will need to be accust -- accust -- become accustomed to. And some of the sights, such as the visuals that I'm going to show you. And in -- in addition to caring for your patient or client and making sure that they have adequate nutrition and making the appropriate recommendations, it's also in your best interest to make sure that this is done, not just to take care of your patient, but also from a professional standpoint. Because there is nothing more that brings, you know, a defense attorney or, I should say, a prosecutor more delight than being able to put these images up and horrify the jury with a particular horrific wound that, for whatever reason, did not heal. It -- it could be negligence on the part of the healthcare staff or team. Usually it's not. It's just the reality of a disease, state, or process in which, you know, nothing short of an act of God was going to heal this ulcer. Nonetheless, lawsuit lottery is the time -- you know, is a -- is a real -- it's a reality. So you just want to make sure that you've done everything you can do for your patient and that you've documented it. Because if you haven't documented it, it never happened. But just be aware of that. These particular cases are getting litigated. Our -- our patients with these particular diagnoses, and that's a tactic that's used. Shock and awe. And, you know, if you have a group of jurors who aren't usual -- aren't used to seeing such things, you know, how do you -- how do you think the jury's going to vote. So enough said about that. So what is a pressure injury? The definition is a localized damage to the skin. And then the -the soft tissue. So the underlying tissue, which is why you need to understand, you know, we have an epidermis, a dermis, and a hypodermis. And what those particular layers consist of. It typically is over a -- a bony prominence. So like your coccyx, your elbow. It can be related to a medical device. So if you've got an NG tube in -- that's a nasogastric tube which they put down through your nose and thread into your esophagus -- that external tubing can cause pressure on the septum of your nose. They're supposed to be switched out -- or, excuse me, the nostril is supposed to be alternated when they're replaced. You know, so as the name implies, you got to have some type of pressure. So if you have a patient that has, you know, a scalp laceration, that's not a pressure injury. Certainly, keep in mind, you know, if you're able to ambulate, then the likelihood of you getting a pressure injury is remote. But people that have, oh, let's say that they've -- that they're a quadriplegic or paraplegic, or they've got MS. Whatever -- whatever the reason, they have an inability to reposition themselves in their beds or their chairs. And so, if you look at the second bullet, you know, they're in a certain position for a prolonged period time, there could be shearing as they try to shift or move or as a care provider tries to move them. And these wounds are always impacted -- you can see I have nutrition in bold -- by nutrition. The formation of collagen, infection, the -- the tensile strength. So after a wound has healed, that area is always, always, always going to be more susceptible to a wound again. Because the skin will never be as strong as it once was. The microclimate. What's the environment like? Is every -- is it, you know, South Texas and it's 95 degrees and everybody is, you know, perspiring 100% of the time with, you know, 110% humidity? Perfusion? What is their vascularity like? How's their blood flow? And what are the comorbidities? Do they have diabetes? Do they have peripheral vascular disease? So there's other factors that come into play. And they're usually very, very painful. Again, but if you have paralysis, you're not going to be able to feel that pain. So as an example, and I'm just laughing because I had this, like, aha! moment. I was on a very long flight and I don't remember why. But I was -- I, you know, think of the airplanes. You have to sit basically in this little tiny seat and you can't stretch your legs. I'm not as tall as I once was, so even with that, though, I was extremely uncomfortable. And my coccyx started to really, really hurt. I was in pain, to the point where I pulled out my purse and took some Ibuprofen. So that's exactly how a pressure area is formed. But I can -- I could constantly kind of shift and wiggle, I mean, to a certain extent. I was kind of boxed in by the other, you know, two passengers that were -- that were sitting on either side of me. That's exactly how it occurs. So you just need to be aware of these things and you need to be ready to look at pictures and discuss with nursing, physicians, providers, what type of recommendations that you might have to help these wounds heal. Okay. So we have basically four types of pressure ulcers. Anywhere you go, this is the way they're staged. Stage 1, you and I might -- could have now. I mean, if I -- I probably had a stage 1 on my coccyx from that long flight. Skin is red, so erythema. My skin is intact. I didn't have a break in the skin. There were no open areas. And it's not blanchable. So if you push on it, it stays red, in other words. Stage 2, the dermis, so the second layer of the skin is exposed. And you have some skin loss. Stage 3, you're getting full thickness of the skin is gone. Excuse me -- full -- full thickness skin loss. And with a stage 4, not only is the skin gone, but you also can see some muscle, tendon, ligament. May see cartilage or bone in the ulcer as well. And these are the very, as you might imagine, serious wounds. When you get into a stage 3, actually, I mean, that's when I really start to take a hard look at the nutrition. The stage 4 is -- oh, I just apologize. I just went over that. I meant to say unstageable. So basically for the unstageable, it means there's slough or eschar. Eschar is kind of like this black, crusty skin, I would describe it as, that's obscuring the view into the wound. So you know there's full thickness of loss of skin and tissue loss. But you can't see how much, to what extent. So that's when they call it unstageable. Now I do now and again, or have in the past, argued with nursing or, you know, someone on the healthcare team because a statement or a comment would be made to me. Why haven't you done or implemented any nutrition interventions for Mrs. Smith? She's got a stage 1 on her coccyx. Well, again, with your assessment, you would say, well, her BMI is normal. Or perhaps she's a little overweight. She eats 100% of her meals. And she is able to ambulate and move about and reposition herself in bed. And it's -- it's not indicated at this time. So, you know, you don't need to be winding nutrition supplements to people for every wound that they have. You really have to talk to nursing, take a look at the photos, look at the comorbidities, look at how they're eating, and then make a decision. There's a number of pieces of the puzzle. But there is, because there's such a focus on these wounds in terms of accrediting agencies, like the State. And there's a federal accrediting agency called [inaudible]. And we have the Joint Commission that comes in and evaluates hospitals. There's a lot of pressure on these providers, clinicians, to make sure that the wounds are being adequately addressed and treated. In addition to the pressure areas or pressure ulcers, there's also something called a DTI or a deep tissue pressure injury. And these again are non -- like stage 1s, they're nonblanchable, except they're a lot more serious. They -they just look like a really bad bruise. And they're purple and red and they're deep. They like -they're punky-looking, squishy for lack of a better term. And they are serious. We did -- I just did mention about the medical device-related pressure injury. It -- it typically will have the shape of whatever device caused it. And they do use a regular staging pressure system for those types of injuries. And let me see if I can move my screen. I'm not sure that I can. I wanted to -- ah, that will work. I just wanted to kind of give you a visual of what the various stages look like. So you can see stage 1 is basically the epidermis. It's that red area. It's what I had on my coccyx. Sorry for the visual, but that's what it would look like. Or if I had leaned on my elbow, you know, fallen asleep or I -- I -- I can't say that if you fell asleep on your elbow for a couple hours, you're going to get a pressure area. But it's -- it's repetitive and chronic. That might -- if it was repetitive and chronic, that might occur. You can see the lipid -- that's the hypodermis right below that, kind of, pink squiggly stuff, which would be the dermis. And then there's some muscle, it looks like, and bone. But as you progress to stage 2, you can see that there's some erosion and then, whoa. Look at stage 3 which is C. Into the -- well, into the dermis and just starting to get into that -- the hypodermis, the fat layer. And stage 4 you're into the muscle. Unstageable, you just can't see. You can see that black-colored discoloration. That's eschar. And the DTI, just to me, looks like a bruise, and punky, and almost looks like a piece of fruit that gets overripened and, like, if you poke it you could poke your finger right through it. That's what it reminds me of. There are also something called diabetic ulcers. And you're going to have a case study about this. And for purposes of what I'm going to talk about, I'm not going to go through the various classifications. You do have some material on that. Typically in a healthcare setting, they don't - they don't get into the weeds like that. It's great information to have. Probably if you went to a diabetic wound clinic they would have that documentation. But in general, these wounds occur on diabetics' feet. Hence the name, diabetic foot ulcers. So what happens, usually, is that there is some neuropathy, meaning they can't feel what they step on. This used to blow my mind. I remember when I first started out, I was a student. I'm thinking, how can you not see what's on your feet? You know, don't you look at your feet? Can't you see your feet? If you painted your toenails, you'd see your feet. So what I didn't realize is that if you can't feel it, then how do you know you stepped on it. And there are literally have been -- we've had patients that have needles, lancets, stuck in their feet. They couldn't feel them. You know, think about leaving a needle in your foot, what type of infection that would cause. Approximately 15% of diabetics are impacted by this. And hyperglycemia, neuropathy, and poor circulation contribute to these -- are -- are factors that contribute to potentially getting a diabetic ulcer. That's why they're always saying, if you're a diabetic, do a routine foot examination. See if there's anything stuck in your foot. You know, if you can't feel that rock or tack or needle that got stuck in your foot, how are you going to know to get it out if you don't look? Here's a picture of a diabetic foot ulcer. They do typically occur around the ankles. That doesn't mean that they're always there, but that's typically what you'd see. And it looks like this one's had some treatment. Looks like there's some bubbling action going on there. I don't know that it's hydrogen -- hydrogen peroxide, but it may be. And nurses are dead set against hydrogen peroxide, which has kind of always been used to clean wounds because it does actually kill healthy tissue. Venous or vascular ulcers, or venous stasis ulcers are a result of vascular system, or circulatory system compromise. And there's an actual breach in the skin. So when they -- when you have -- veins that aren't functioning the way they normally should. You know, you have valves that don't work so the blood isn't -- it's flowing backwards. It's not headed to the heart and it kind of pools. Hence the statis term. And you get skin breakdown. It's chronic. It's long term. They're horribly hard to heal. And there's that increased risk of infection with this pooling blood that's not really circulating. And then once you have a breach in the skin, you're -- you could get any type of infection, you know, depending what you encounter in the world. And the contributing factors -- I've listed hypertension and atherosclerosis, but obesity is also a contributing factor. There's some genetics there. We know that varicosities, varicose veins, have a genetic component. So there is that factor as well. And they have got some great technology now, modalities of treatment to get rid of those varicosities for folks who are suffering with them. They're -- they're quite painful. Here's a vascular ulcer and this one, I believe, they said the etiology or the cause, the root cause, was obesity. But you can see why that would be difficult to heal. And a lot of hospitals now have their own wound clinic. In fact, there's a place where I consult that they actually send some patients to the larger medical center wound clinics because the wounds are so, so difficult to heal sometimes. Despite the interdiscipline -interdisciplinary team's best efforts. You know, the reality is some of them are very, very hard to heal. And some of these folks end up having grafts -- so skin grafts -- or wound flaps where they actually have to take tissue from other parts of the body and graft it over the wound just to get it covered and to get it to heal. Often that's done by plastics. So plastic surgeons will do that. So I think I've covered what I want to for today. I will see you for the next lecture. Thanks. Have a great day. Bye-bye now.