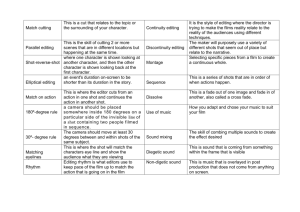

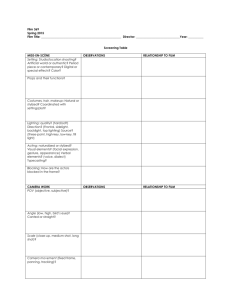

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/264699645 Editing and the production of new meanings in films Article · February 2014 CITATIONS READS 0 806 1 author: Giuseppe Pagano Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin 5 PUBLICATIONS 0 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE All content following this page was uploaded by Giuseppe Pagano on 13 August 2014. The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file. HUMBOLDT UNIVERSITÄT ZU BERLIN BERLIN IN FILM - FILM IN BERLIN EDITING AND THE PRODUCTION OF NEW MEANINGS IN FILMS TERM PAPER GIUSEPPE PAGANO INDEX INDEX .............................................................................................................................. 1 INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................................... 2 1.1. EDITING: IN QUEST OF A DEFINITION .......................................................... 3 1.2. FILM SYNTAX ..................................................................................................... 3 1.3. KULESHOV EFFECT ........................................................................................... 6 2.1. EDITING IN PRACTICE ...................................................................................... 7 2.2. THE POINT OF VIEW EDITING IN THE FILM ‘DER HIMMEL ÜBER BERLIN’ ............................................................................................................... 7 CONCLUSIONS ........................................................................................................... 12 BIBLIOGRAPHY AND SITOGRAPHY ................................................................... 13 1 INTRODUCTION Editing represents a tool through which, in a film, the director achieves the production of new meanings. The single image might, in fact, transmit to the viewer a different meaning than the one perceived from its combination with additional images. This work aims to demonstrate this thesis and to explain, in a short but at the same time thorough way, how the viewer mostly tends to make connections between the different scenes, shots and even single frames of the film and how the combination of images (montage) can produce new meanings. Moreover, a fundamental aspect of this thesis will be the focus and the investigation of a film belonging to the German film history, i.e. ‘Der Himmel über Berlin’. Thus, I will try to prove how the employment of a specific editing technique, i.e. the ‘point of view editing’, has permitted the film director Wim Wenders to convey to the viewers ideas and meanings which would not have been communicated in the same way without this technique. The term paper begins with a short introduction to the definition of the term ‘editing’, and continues then in the explanation of the ‘film syntax’, focusing on technical notions such as frame, shot, scene and sequence. The ‘Kuleshov effect’ is also investigated. In the second part of this term paper it is explained how editing works in practice and, more specifically, how point of view editing is employed in the film ‘Der Himmel über Berlin’ with specific examples. The term paper is completed with the realization of videos which have the purpose to explain in a clearer and visual way what already explained in written word. The term paper, considering time and given indications, does not have the aim to explain subjects in depth, something which not even whole manuals always achieve. Nonetheless, it will be tried to give the reader a clear comprehension of the discussed topics and, hopefully, an input into further research. 2 1.1. EDITING: IN QUEST OF A DEFINITION There is not a univocal definition of the term ‘editing’, which, additionally, is often used as synonymous of ‘montage’ or ‘cutting and splicing’1. However, the different definitions which have been found are all unanimous in defining ‘editing’ as a process which allows the combination of basic cinematographic elements (usually shots) in order to create bigger sets (scenes, sequences, cinematic wholes et cetera): “Film editing is a generic term for a complex process which structures the film development, selects, arranges and organizes its visual and acoustic elements …”,2 and here explained even more clearly: “Editing … is the process by which the editor combines and coordinates individual shots into a cinematic whole”.3 Certainly, the process of editing is fundamental in the creation of new meaning, as can be deduced by this quotation which defines ‘editing’ as: “… the creation of a sense or meaning not proper to the images themselves but derived exclusively from their juxtaposition.”4 VIDEO 01: How editing produces new meaning 1.2. FILM SYNTAX Cinema, like other art forms, such as music, can be considered as a system of signs which combine with one another: “Films consist of pictures. The concrete film experience reveals itself as living connected images, or rather picture sequences.”;5 “A film is made up of a chain of shots.”6 Moreover, cinema is a downright language which has its own syntax and its own codes. The basic element of this language, the one which in natural languages would be defined as morpheme, is the The terms ‘cutting’ and ‘splicing’ derive from the fact that, before the digital era, the various shots had to be cut from the roll film and spliced, in order to edit. Barsam R, Monahan D. Looking at movies, an introduction to film. 3rd ed. New York: W.W. Norton & Company; 2010: 320. 2 Translation by the author: “Filmmontage ist eine Sammelbezeichnung für einen komplexen Vorgang, der den Film in seinem Ablauf strukturiert, seine visuellen und akustischen Elemente auswählt, anordnet und sie organisiert …”. Beller H. Handbuch der Filmmontage: Praxis und Prinzipien des Filmschnitts. 5th ed. TRVerl.-Union; 2005: 78. 3 Barsam R, Monahan D. Op Cit: 320. 4 Dudley A, Joubert-Laurencin H. Opening Bazin, postwar film theory & its afterlife. New York: Oxford University Press; 2011: 291. 5 Translation by the author: “Filme bestehen aus Bildern … Das konkrete Filmerlebnis stellt sich als ein Erleben von zusammenhängenden Bildern bzw. Bildfolgen dar …”. Borstnar N, Pabst E, Wulff HJ. Einführung in die Film- und Fernsehwissenschaft. 2nd ed. Konstanz: UVK Verlagsgesellschaft; 2008: 97. 6 Translation by the author: “Ein Film besteht aus einer Kette von Einstellungen.” Hickethier K. Film- und Fernsehananalyse. 3rd ed. Stuttgart: Metzler; 2001: 52. 3 1 single frame: “The smallest unit of film editing is the cinematic frame on the exposed photographic film.”7 These small units, in a fast sequence, are assembled by our cognitive system as if they are part of a whole; this gives us the impression of a moving image. Indeed, cinema might be considered as a real illusion. The first remarkable experiments in these terms were conducted by Eadweard Muybridge who, through the employment of a ‘phenakistoscope’ and a sequence of images of running horses taken by himself, created the illusion of an animal in movement.8 Two are the principles which permit static images to be seen as motion images. The first one has been defined in psychology as ‘Phi phenomenon’: “This impression of movement which is achieved through the gradual presentation of stationary frames is investigated in perceptual psychology as Phi-phenomenon ... : frames in succession merge in a general impression, which is more than the sum of its parts.”9 Therefore, a fast succession of static images is perceived by our cognitive system as a whole and assembled together. This gives us the perception of motion. As a matter of fact, according to the Czech psychologist Max Wertheimer who discovered the ‘Phi phenomenon’, this is caused by the tendency of our perception to associate various inputs in indivisible structures.10 A second phenomenon, not less interesting and fundamental in the production of movement, is the ‘Afterimage phenomenon’. This is an effect in which an image keeps on holding in our visual perception for a short time, also after the source of light has ceased. “An afterimage is a type of optical illusion in which an image continues to appear briefly even after exposure to the actual image has ended.” 11 VIDEO 02: Cinema as illusion Translation by the author: “Die kleinste Einheit der Filmmontage ist das filmische Einzelbild auf dem belichteten Filmstreifen.” Beller H. Op Cit: 9. 8 Something similar was developed by Max Skladanowsky in the same period with the ‘Daumenkino’. 9 Translation by the author: “Dieser Bewegungseindruck, der durch die sukzessive Darbietung ruhender Einzelbilder erzielt wird, wurde in der Wahrnehmungspsychologie als Phi-Phänomen untersucht …: Aneinandergereihte Einzelbilder verschmelzen zu einem Gesamteindruck, der mehr ist als die Summe seiner Teile.”. Beller H. Op Cit: 9. 10 Wertheimer M. Experimentelle Studien über das Sehen von Bewegung. Zeitschrift für Psychologie 1912; 1: 161-265. Available at the following internet address: http://gestalttheory.net/download/Wertheimer1912_Sehen_von_Bewegung.pdf (consulted on 26th December 2013). 11 Cherry K. What is an Afterimage?. About.com Psychology. Available at the following internet address: http://psychology.about.com/od/sensationandperception/f/afterimages.htm (consulted on 26th December 2013). 4 7 A definite amount of frames makes up the single shot, defined as: “… one uninterrupted run of the camera … as short or as long as necessary…”.12 In other words: “We name ‘shot’ what, in a film, is situated between two cuts. This shot is made up of single pictures and, according to the rule needs, 24 of them per second in a film.”13 The first films were single shot movies; a renowned example is ‘L'Arrivée d'un train en gare de La Ciotat’ by Lumiere brothers and, as regards to the German cinema, ‘Das Boxende Känguruh’ by Skladanowsky brothers. In those film there is not, therefore, any kind of editing. VIDEO 03: The first films In later films and, more in general, in modern cinema, except from rare circumstance (such as the Andy Warhol’s films ‘Empire’ and ‘Sleep’, but also in theatrical representations taken by a camera)14, numerous shots are combined to create longer and more complex units named scenes, that is: “A complete unit of plot action incorporating one or more shots …”.15 “The scene is traditionally determined as a unit of space, time, action and people … Therefore, the scene is rather a content category, which already before the completion of the film represents a cohesive unit …”.16 The last structural film unit in order of complexity is the ‘sequence’, defined as: “A series of edited shots characterized by inherent unity of theme and purpose.”17 In other words, the ‘sequence’ is: “… a piece of film, that is to say an episode, connected graphically, spatially, chronologically, thematically and/or scenically which forms itself in a self-contained unit.”18 VIDEO 04: Film syntax 12 Barsam R, Monahan D. Op Cit: 210. Translation by the author: “Das, was sich in einem Film zwischen zwei Schnitten befindet, nennen wir eine ‘Einstellung’. Diese Einstellung setzt sich aus einzelnen Bildern zusammen, wovon in der Regel 24 pro Sekunde im Kinofilm … benötigt werde.” Hickethier K. Op Cit: 52. 14 Hickethier K. Op Cit: 52. 15 Barsam R, Monahan D. Op Cit: 557. 16 Translation by the author: “Traditionellerweise wird die Szene … als Einheit von Raum, Zeit, Handlung und Personen bestimmt… Die Szene ist also eher eine inhaltliche Kategorie, die bereits vorfilmisch eine geschlossene Einheit darstellt…”. Borstnar N, Pabst E, Wulff HJ. Op Cit: 152. 17 Barsam R, Monahan D. Op Cit: 557. 18 Translation by the author: “… ein Stück Film bzw. eine Episode, die grafisch, räumlich, zeitlich, thematisch und/oder szenisch zusammenhängt und eine relativ autonome, in sich abgeschlossene Einheit bildet.” Bornstar N, Pabst E, Wulff HJ. Op Cit: 152. 5 13 1.3. KULESHOV EFFECT One fundamental principle on which the editing is based is the fact that the viewer tends to interpret the single shot as connected to those immediately preceding or following it. What usually happens inside a film is that a shot, which follows another one, gives automatically to the viewer the sensation that it, let’s say shot B, is the consequence of what happened in the first shot, let’s say shot A, and that both shots are connected by spatial and temporal relations. VIDEO 05 – The relations between shots The power of this effect was demonstrated with an experiment by Lev Kuleshov in 1918: in a short video three different shots (a dish of soup, the body of a child in a coffin and a woman on a sofa) are followed by the identical close-up of an actor’s expressionless face. The viewers were asked what they would deduce from the actor’s expression and answered: hunger in regards to the shot edited with food, tenderness in regards to the shot edited with the child and desire in the shot followed by the woman on the sofa; while, indeed, the actor’s expression remained the same.19 Kuleshov, with this experiment, taking into consideration the natural attitude of the viewer to create logical connections between the single shots, wanted to give evidence to the fact that the single shot takes on meaning as a result of what is showed before. To sum up: “The Kuleshov effect proffers the principle that, in absence o fan establishing shot, a viewer will infer a spatial relation between discrete shots. In other words, when presented with a series of shots, viewer assumes or constructs a relationship of space, time and/or narrative among them.”20 VIDEO 06 – The Kuleshov effect 19 Barsam R, Monahan D. Op Cit: 320. Several variants of the experiment are present. 20 Wojcik P. Movie acting – The film reader. New York: Routledge; 2004: 4. 6 2.1. EDITING IN PRACTICE The director, who in a film wants to create specific meanings or who has the purpose to make his film more enjoyable for the viewer (with, for instance, continuity21), can make use of specific editing techniques or rules. Mentioning only some of them, we will refer to ‘180 degree system’, ‘shot-reverse shot’, ‘graphic match cut’, ‘master shot’, parallel editing and so on. This term paper does not aim at analyzing all the single techniques,22 but focusing only on one of them and examining how it is used by the director to produce meaning. In fact, technique, in the same way as it happens in many arts such as music, dance, painting, should not be considered as an aim, but on the contrary as a tool. Great artists do not apply technique in a schematic way, but employ it as an instrument which allows them to communicate ideas, feelings or thoughts in a flexible and creative way. 2.2. THE POINT OF VIEW EDITING IN ‘DER HIMMEL ÜBER BERLIN’ ‘Der Himmel über Berlin’, realized in 1987 by Wim Wenders, is a film which “… has prompted a torrent of commentary, exegesis and discourses like no other film of Wenders” 23 ranging over many topics, from commentaries focused on the importance of physicality, to those focused more on desire and (spiritual) eroticism, to those focused on the historical background, isolation and division portrayed by Berlin in the film.24 Beyond the single interpretations, which are actually not much relevant to this exposition, we might start considering the film ‘Der Himmel über Berlin’ as a representation of an angels’ story or, at least, we might state that angels (with all the consequent correlations, that is to say their thoughts, meditations, point of views and doubts – because, in this film, also angels ask themselves questions) are the protagonists of the film25 and take on an important role. ‘Continuity editing’ is the one which allows a fluid passage through the different film shots, in order to avoid that the viewer notices the ‘cuts’. 22 Whoever is interested in deepening editing techniques can refer to a good manual such as: Reisz K, Millar G. The technique of film editing. 2nd ed. Burlington: Focal Press; 2010 / Barsam R, Monahan D. Op Cit: 319-66 / Dancyger K. The Technique of Film & Video Editing. 5th ed. Burlington: Focal Press; 2011. 23 Brady M, Leal J. Wim Wenders and Peter Handke: Collaboration, Adaptation, Recomposition. Amsterdam: Rodopi B.V.; 2011: 243. 24 Kolker RP, Beicken P. The films of Wim Wenders - Cinema as Vision and Desire. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1993: 138-60 / Künzel U. Wim Wenders - Ein Filmbuch. 3rd ed. Freiburg: Dreisam Verlag; 1989: 199-209 / Cook RF, Gemünden G. The Cinema of Wim Wenders: Image, Narrative, and the Postmodern Condition. Detroit: Wayne State University Press; 1997: 163-87. 25 Ibid: 167. 7 21 Indeed, the German director Wim Wenders “Sensing the importance of Berlin both as a bridge to the past and as a pivotal city for peaceful coexistence in the world … arrived at the idea for the film: angels living in Berlin preserve the memory and even presence of Germany’s history, while helping the inhabitant bear the burden of their nation’s past.”26And in confirmation of this, Wenders “… described the mobile camera as embodying the point of view of angels. In this connection, he told of the production team's efforts to use the camera in such a manner that it would ‘translate the way angels might see;’ and ‘to seek continually the angel's point of view, the camera becoming his gaze.”27 Once ascertained that the film represents the city of Berlin through the eyes of angels, it is interesting to analyse how the German director has called on editing techniques, and more in detail how Wim Wenders has drawn on ‘point of view editing’ to represent the angels’ gaze. The ‘point of view editing’28 is a technique which permits to give continuity to the editing, connecting two or more shots. It consists in presenting a character who is watching something or somebody and then, in the following shot, in showing what is watched by his/her eyes: “… point of view editing is used to cut from shot A (a point-of-view shot, with the character looking toward something offscreen) directly to shot B (… what the character is looking at). Point of view editing is editing of subjective shots that show a scene exactly the way the character sees it…”29 However, it is not rare to find reverse patterns where it is shown, at the beginning, what is watched by the character and, only after, the character him/herself watching. In some cases, the character is not even displayed, but it is shown only what he/she is watching; in these situations, the fact that we are dealing with ‘point of view’ is deduced by other details. Moreover, it is important to avoid confusion between ‘POV editing’ and ‘eyeline match’. These two techniques are similar but, as claimed by two important cinema experts (i.e. Barsam R. and Monahan D.30), they differ one from the other: “… be careful not to confuse point-of-view editing with, say, the eye-line match cut, which joins two comparatively objective shots, made perhaps by an omniscient camera.”31 VIDEO 07: Point of view editing 26 Ibid: 164. Raskin R. Camera Movement in the Dying Man Scene in Wings of Desire. A Danish Journal of Film Studies. 1999 Dec; 8: 157. Available at the following internet address: http://pov.imv.au.dk/pdf/pov8.pdf (consulted on 1st February 2014). 28 From now on we will mainly refer to ‘point of view editing’ with the acronym ‘POV editing’. 29 Barsam R, Monahan D. Op Cit: 347. 30 Ibid: 344. 31 Ibid: 347. 8 27 The film by Win Wenders is rich of ‘POV editing’ in which the character is immediately followed by what he sees. A classic example is present in the scene when Damiel decides to go to the concert of ‘Nick Cave & The Bad Seeds’. In three shots we can see Damiel who walks and passes in front of a poster of the concert, stops, watches in its direction and in the following shot it is shown exactly what he watches with his eyes. Certainly there are numerous other examples in the course of the film. On the other hand, in the scene with the motorcyclist incident the ‘POV editing’ works differently; the character, in this case, is shown only after what is watched by him. “We see through the eyes of someone gliding rapidly across a bridge…”,32 we might say through the eyes of Damiel who, at the end of the shot, watches towards the dying motorcyclist. In the following shot, the angel is shown with his face in direction of the man with an angle approximately similar to the one of the gaze in the previous shot. Another example, maybe more clear, is situated in a scene in the camping van where it is displayed what Damiel watches and, after that, the angel himself. VIDEO 08: The ‘POV editing’ in ‘Der Himmel über Berlin’ A really interesting case can be observed in the sequence in the library. In a precise shot is employed the ‘POV editing’ which shows us what the character sees but not the character anymore. However, despite the fact that the viewer does not directly see the character, it is easy for him/her to assume that we are dealing with an angel: “ … the first library scene begins with the camera aimed at the ceiling and slowly tilting downward as it is lowered. The camera then glides horizontally past people reading at tables, and when it passes a woman in an overcoat with her hand resting on the shoulder of someone reading, the woman in the coat turns and nods a greeting toward the camera … The woman's nod toward the camera tells us simultaneously that we are seeing through the eyes of an angel and that she herself must also be one.”33 Something similar takes place in the next shot. Not less noteworthy is the scene in which Columbo feels the presence of Damiel in front of a street trader. In this case, Columbo is firstly shown and after him there is a shot which, at first glance, seems to be a ‘POV editing’, that is what Columbo sees (i.e. the angel Damiel). However, no ‘POV editing’ is in question in this example, since Columbo (and the scene itself) confirms that, although he feels this presence, he cannot see him. Therefore, it is not reasonable to declare something Columbo cannot see as his point of view, and we are more likely dealing with an omniscient camera (and thus viewer). VIDEO 09: ‘POV editing’ and some interesting cases in the film ‘Der Himmel über Berlin’ 32 33 Raskin R. Op Cit: 160. Ibid: 157-8. 9 On the other hand, describing the scene where a dialogue between Damiel and Columbo takes place (during the shooting of the Nazi film) we will refer to the employment of ‘eyeline match’ (contained in a shot-reverse shot) instead than ‘POV editing’. Although it is shown what the character watches, in this case this is not displayed through his eyes, but through the use of an omniscient camera and a point of view external to the embodied characters. Furthermore, there are still some borderline cases. For instance, in the scene where Damiel sets off to the concert and stops in front of a television is not clear which one of the two techniques is employed. At any rate, analyzing the scene more carefully, both techniques can be excluded since the three televisions shown in the three shots are all different. VIDEO 10: ‘Point of view editing’ and ‘eyeline match’ The director’s choice to depict the point of view of angels through the ‘POV editing’, hence, turns to be interesting both for narrative purposes (What do the angels watch and think? How it is their relationships with the mankind? What doubts and uncertainties do they have? – in Wenders’ film even angels ask themselves existential questions!) and for technical ones (employment of black and white, editing choices, camera movements etc.). In terms of narration, for instance, it seems clear that the elements and facts of reality which are worth to be shown in the film are determined by the angels and they are mostly depicted through their point of view. Not less interesting is the fact that the ‘POV editing’ allows the viewer to understand that what is seen by him/her can be attributed to the angels’ gaze (during these shots angels are not noticed by human beings, moreover, they stay next to people without being watched) and that the only ones able to see them are children: “The initial shot/reverse-shot sequence occurs with Damiel, complete with wings, standing on the tower of the Gedächtniskirche. From his perspective we see a young girl below who has stopped in the middle of the crowded crosswalk and is looking up at him while the adults go about their business without seeing him. This shot and the subsequent ones of the two girls on the bus and the child on the airplane establish that the protagonist is invisible except to children and angels.”34 Also further scenes confirm this perspective. Furthermore, the reassuring way with which the children look to the angels’ gaze reveals to the viewer further information about the angels themselves, namely their positive influence on the surroundings, and thus conveys a sensation of calm and peace to the viewer: “The unthreatened and nonthreatening looks the children direct at the angels, many of them directly into the camera, mirror the benevolence in the look of the angels.”35 VIDEO 11: ‘Point of view editing’ and narration 34 35 Cook RF, Gemünden G. Op Cit: 168. Ibid: 168. 10 Finally, the director’s choice to show the viewer what angels see portrays an interesting and noteworthy factor also from a technical perspective. Indeed: “Locating the camera as the eye of an angel presented constant challenges during the shooting and resulted in innovative solutions, particularly in terms of the camera movement, which was to give the illusion of unlimited movement through space and time.”36 This feeling of boundless and free movement is already found in the first scenes, where the city of Berlin is shown from above, probably from the eyes of an angel: “From an all seeing eye, a dissolve takes us on a flight around the Himmel über Berlin … and in and out of the lives and minds of people. This bird's-eye view lets us hear and see everything from an angel's-eye-view.”37A similar scene is present again some minutes later in the film. The technical challenge to portray the angels’ point of view is even more noticeable in the scene where Cassiel jumps from the Victoria Statue and in which shots from the cities are shown: “The most spectacular example of camera movement as angelic point of view in this film, is undoubtedly the montage sequence … , which is introduced by a shot in which Cassiel punge from the wing of the Victory Statue … , after which the camera takes a similar plunge … and we see – through Cassiel's eyes –and in dizzying succession, a cascade of fragmentary urban images, some of which are quite disturbing.”38 VIDEO 12: ‘Point of view editing’ from a technical perspective 36 Ibid: 167-8. Raskin R. Op Cit: 104-5. 38 Ibid: 158. 37 11 CONCLUSIONS The starting assumption, whereby the employment of editing allows to convey meanings and to manipulate these according to the director’s taste, has been largely confirmed. We have actually seen how the viewer already tends to see more than what is really projected on the screen, how this phenomenon has already been investigated in psychology and how it permits the illusion of cinema. Moreover, we have described how the viewer is inclined to correlate the single shots one another and how this allows him/her to give the single shot new meanings. We have had a further confirmation of this principle through the analysis of the ‘Kuleshov effect’. In addition, we have referred to the practical use of a specific editing technique, i.e. the ‘point of view editing’. It has been shown how, in this case too, the viewer spontaneously links two shots together and how this fact is exploited by the director (also in an artistic way) to represent and show the point of view of the film characters. Finally, this term paper has dealt with some particular cases of ‘point of view editing’ showing how in some circumstances the standard pattern of this technique can be reversed and how the character might even not be present after his/her point of view shot. To sum up, this work has tried and tries to be a good starting point for those who want to deepen the editing topic. For the cineaste (but also for the ordinary man), editing itself and its knowledge is necessary to a better understanding of the world of cinema and, why not, to set out for the realization of a film. 12 BIBLIOGRAPHY Barsam R, Monahan D. Looking at movies, an introduction to film. 3rd ed. New York: W.W. Norton & Company; 2010. Beller H. Handbuch der Filmmontage: Praxis und Prinzipien des Filmschnitts. 5th ed. TRVerl.-Union; 2005. Borstnar N, Pabst E, Wulff HJ. Einführung in die Film- und Fernsehwissenschaft. 2nd ed. Konstanz: UVK Verlagsgesellschaft; 2008. Brady M, Leal J. Wim Wenders and Peter Handke: Collaboration, Adaptation, Recomposition. Amsterdam: Rodopi B.V.; 2011. Cook RF, Gemünden G. The Cinema of Wim Wenders: Image, Narrative, and the Postmodern Condition. Detroit: Wayne State University Press; 1997. Dancyger K. The Technique of Film & Video Editing. 5th ed. Burlington: Focal Press; 2011. Dudley A, Joubert-Laurencin H. Opening Bazin, postwar film theory & its afterlife. New York: Oxford University Press; 2011. Hickethier K. Film- und Fernsehananalyse. 3rd ed. Stuttgart: Metzler; 2001. Kolker RP, Beicken P. The films of Wim Wenders - Cinema as Vision and Desire. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1993. Künzel U. Wim Wenders - Ein Filmbuch. 3rd ed. Freiburg: Dreisam Verlag; 1989: 199-209 Reisz K, Millar G. The technique of film editing. 2nd ed. Burlington: Focal Press; 2010 Wojcik P. Movie acting – The film reader. New York: Routledge; 2004: 4. SITOGRAPHY Cherry K. What is an Afterimage? About.com Psychology. http://psychology.about.com/od/sensationandperception/f/afterimages.htm (consulted on 26th December 2013). Raskin R. Camera Movement in the Dying Man Scene in Wings of Desire. A Danish Journal of Film Studies. 1999 Dec. http://pov.imv.au.dk/pdf/pov8.pdf (consulted on 1st February 2014). Wertheimer M. Experimentelle Studien über das Sehen von Bewegung. Zeitschrift für Psychologie 1912; 1: 161-265. http://gestalttheory.net/download/Wertheimer1912_Sehen_von_Bewegung.pdf (consulted on 26th December 2013). 13 View publication stats