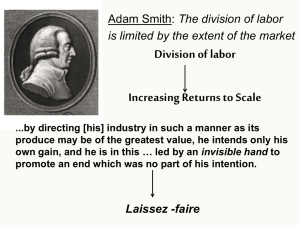

THE KEYNESIANS – CLASSICALS MACRO ECONOMIC SCHOOL OF THOUGHT DEBATE 1. Introduction The Keynesians are a group of macro economists who generally favour activist government involvement in the economy. On the other hand, the classicals are group of macro economists who generally favour non-activist government involvement. Specifically, they believe in nongovernment involvement in the businesses of the economy. The classicals argued that government involvement in the economy leads to greater instability in the macroeconomic system and that the proper role of the government is to provide an enabling environment for private sector driven economy. That is the provision of security, the maintenance of law and order, and allows the private sector to undertake the businesses of the economy. Deducing from the definition of who the Keynesians and classicals are, we noticed that the primary motive of the Keynesians – Classicals debate was whether government should be involved (Keynesians argument) or not to be involved (Classicals argument) in the business of the economy, and not primarily a matter of the use of fiscal or classicals policy in economic management as erroneously claimed by some economists. 2. Cause of the Debate In the early 1930 the microeconomics concepts of the classicals and neoclassicals economists was the dominant economic philosophy of the time, operating on the assumption of perfect competition, wages and price flexibility. The economy was assumed to be self-correcting and equilibrium income would always tend towards it full employment level, especially in the long run. As the classicals system shows, these concepts were accepted and for a long time formed the corpus of economic knowledge from which policies were drawn. Governments were admonished not to intervene in the event of any dislocation arising, say from inadequate aggregate demand. The events of the great depression (1929 – 1993) shook the very foundation of classicals economic theory. The prescriptions by the classicals economists could not provide the much needed remedy. There was much confusion regarding what should be done. Galbraith (1972) has extensively documented how renowned economists like Irving Fisher misunderstood the crash and in the classicals tradition argued that the panic that accompanied the great crash was unfounded. 1 3. The Debate: Keyne’s View Keyne’s General Theory was written as an attempt to put forward solutions to the method of economic analysis in the context of the great depression. According to his line of analysis the economy is not self-adjusting. Keynes based his analysis essentially on the short run (since in the long run we would all be dead). He argued forcefully that the possibility of equilibrium income inconsistent with full employment was real. Indeed, such a less than full employment income could not be remedied by the free forces of demand and supply in the three markets (labor, products and money). This creates involuntary unemployment. He urges the government to intervene to eliminate the deflationary gap which the free interplay of the forces of demand and supply in the markets has been unable to eliminate. He thus advocated government intervention to cure the unemployment in the economy. This could be achieved through fiscal policies by either increasing government spending and reducing taxes or imposing higher taxes to restrict/curtail aggregate demand when the economy is heated up. Furthermore, some contributions during the period were readily adopted by the traditional Keynesians to fill the void inherent in the Keynesian framework. For example, the IS-LM model assumed a fixed price level at less than the natural rate of output/unemployment such that aggregate demand shocks will affect only the level of output and employment with no inflationary pressures. So, when the publication of A.W. Philips statistical investigation into the relationship between the level of unemployment and wage inflation came out in 1958 and Lipsey (1960) provided the theoretical rationale for the curve (Santomero & Seater 1978), orthodox Keynesian economists quickly adopted it for three main reasons. First, it provided an explanation of price determination, and inflation, which was missing in the then prevailing macroeconomic level. In separate contributions to the theory of money demand after Keyne’s contribution, Baumol (1952) and Tobin (1958) demonstrated that people choose between holding money balances and securities (i.e. bonds/equities). In other words, by assuming that people trade off money balances for securities, or vice versa they demonstrated the effects of interest rates in transaction (Precautionary) motive. This implied that higher market rates increase the opportunity cost of holding real money balances for transaction/precautionary purposes. The result is that individuals hold less money; therefore, 2 income velocity of money will rise. The converse is true for a decrease in market interest rate. Recently, David Rome (1986) expanded the Baumol-Tobin approach to address the effects of shifts between money and non-classicals assets in the economy. Other significant contributions in different directions during the period analyzed the “short – run fluctuations around the trend” as well as the “long run movement of output by identifying the determinants of the trend and ignoring fluctuations around the trend”. While the analyses of the short run fluctuations around the trend had at the centre the Hick – Hansen IS-LM framework (Hicks 1937; Hansen 1953 and Darity & Young 1995), the long – run movements of output were, in essence, significant contributions to the development of growth. The instability and the apparent volatility introduced into the money demand functions by Keynes were at the core of classicals counter attack on Keynesian economics. 4. The Debate: Classicals’ View In the mid-1950s and 1960s, Milton Friedman began a steady and systematic three-way assault on Keynesian economics in the attempt to “re-establish the quantity theory of money approach to macroeconomic analysis which had been usurped by the Keynesian revolution”. Friedman’s initial assault started with the restatement of the quantity theory of money in 1956 to counter the three motive specific analysis of money demand provided by Keynes. Friedman’s restatement was meant to limit the quantity theory to a theory of the demand for money as well as the proposition that money matters, and not just a theory of the general price level or money income (Laidler 1981). To show the stability of the money demand function, Friedman included permanent income because it does not vary much with the business cycle. Based on this, he asserted that the money demand and velocity functions were highly stable and would only change in a predictable manner if any of the variables in the demand for money function should change (Laidler, 1993). In a continuation of the assault on Keynesian economics, Friedman and Schwartz (1963) provided the most persuasive evidence to support the notion that “changes in the stock of money play a largely independent role in cyclical fluctuations”. According to Friedman and Schwartz, episodes of absolute fall in money stock corresponded to the six periods of major economic contractions over the 1867- 1960 periods. In Friedman and Schwartz’s view, the Grate Depression was as a “consequence of the failure of the Federal Reserve Bank to prevent a dramatic decline in the money stock between October, 1929 3 and June 1933. They interpreted this as a demonstration of the potency, rather than the ineffectiveness of classicals change and classicals policy (Hammond 1996). Arguing on the side of the classicalss, a number of scholars, Lucas (1972, 1973, 1976, 1980) Sargent (1972, 1976a), Sargent and Wallace (1973, 1975, 1976), Barro (1976, 1979) and others, dissatisfied with the Keynes conventional macroeconomic model shave suggested the use of rational expectations approach to economic modeling. Lucas (1976) has emphatically argued that the kind of short-run policy that is usually undertaken with macroeconomic models is not capable of giving dependable results because individuals’ behavior in forming expectations is a function of their perceptions of the policy rule being followed which the Keynesians analysis could not account for. The application of the rational expectations thought to macroeconomic management can be explained by the accelerating inflation typical of the 1970s which made adaptive expectations untenable; the stagflation of the 1970s confounded earlier Keynesian optimism with the Philips curve apparently experiencing increasing instability and collapse; and parallel developments in general equilibrium theory (Anyanwu, 1993). Furthermore, the central though of the rational expectation school is that no government macroeconomic policy, whether classicals or fiscal, no matter how excellently formulated and how effectively, implemented, can have any sustained impact upon real economic variables (Lucas, 1972, 1978; Sargent and Wallace, 1975, 1976; and Barro, 1976). This seriously questions the Keynesian interventionist demand management philosophy, noting that any random policy shifts in aggregate demand will affect real variables and such random actions are not likely to move the economy closer to the realization of desired economic objectives. This development justifies the need for earlier policy rules as postulated by Friedman (1968), as opposed to Keynes philosophy if active intervention in the economy management (Kydland & Prescott, 1977). The post-Keynesian macroeconomists also challenge the applicability of the rational expectation thought. Despite Willies (1981), and Sargent and Wallace (1975) insistence on announcement of free information, Anderson (1986), King (1982, 1983), Shiller (1978), Okun (1980), Harris and Homsstrom (1983) note that the government may use an information advantage to influence the variance of real variables. Again, Weiss (1980) and Turnovsky (1980) made a case for the effectiveness of stabilization policy when some group of persons in the private sector posses’ better 4 information than others. According to Akpakpan (1999), the classicals have a profound distrust of government and a political process. Politicians (Government) are seen as guided often by politics, not by society best interest. For this reason they (classicals) argued that government cannot be relied upon to deal with the problems of the economy. While the Keynesians tend to see government as an expression of the will of the people; therefore, to them, the government can be used to correct the problems of the economy. The Keynesians further stressed that the abuse of government power by interest groups was part of the cost of having government; generally the benefits of government outweigh the cost of not having government involved in the business of the economy. 5. Global Context of the Macro Economic School of Thought According to Bamidele (2001) the management of the national economy is concerned with the determination of the general price level, unemployment, national income and other economic aggregates, which entail setting up of some objectives as a matter of deliberate policy to achieve social welfare. The direction of the global economy towards the classicals thinking of less or limited involvement of government in the business affairs of many countries. This is very obvious considering the economic management approach of privatization adopted by some government in recent times, which allows for less participation of government and grater or increased private sector participation in the world economy. This leads to the conclusion that the initial Keynesians economic thinking adopted in the management of the world economy prior to 1987 had not achieved the desired economic objectives, probably due to mismanagement perpetuated by high scale corrupt practices by government managers of these public enterprises; hence the “Uturn” to the classicals economic thinking for rapid and sustained economic growth and development of the world economy. It is the belief that the economic management ideas of the classicals of private sector driven economy as it is currently going on, should be sustained for a meaningful and rapid growth and development of every nation. Also the role of the public sector (government) in the management of the economy should be reduced and rationalized. Government should basically be involved in the building of infrastructure, development and maintenance of law and order and setting the philosophy, rules and regulations for economic management. If by this arrangement, the private 5 sector is given more prominence in the running of the economy, labor would move naturally from the public to private sector. Furthermore, the relative efficiency of the public and private sectors as an engine of growth may be controversial; the general evidence is that the promotion of the private sector as a catalyst for economic growth is well pronounced much more than the public sector and is supported by substantial empirical evidence. This does not in any way ignore the contributions by the public sector in economic growth and development. Finally, the maintenance of political stability, peaceful atmosphere devoid of terrorist activities and religious crisis in some part of the world are very crucial as a precondition for an enabling environment for sustained and satisfactory private sector led economic growth. 6 References Akpakpan, E.B (1999). The Economy: Towards a New Type of Economics. Belpot (NLS) Co. Port Harcourt, Nigeria Anderson T.M. (1986). Pre-set Prices, Differential Information and Monetary Policy. Oxford Economic Papers 38(3). Anyanwu, J.C. (1993). Monetary Economics: Theory, Policy and Institutions. Hybrid Publisher, Ltd, Owerri Nigeria. Bamidele E.O. (2001). Policy Issues in Nigeria’s Macroeconomic Management. NES Publication. Selected Paper for 1998 Annual Conference, Nigeria Economic Society. Barro, R.J. (1976). Rational Expectation and the Role of Monetary Policy. Journal of Monetary Economics. 2(1). Barro, R.J. (1979). Second thoughts on Keynesian, Economics. American Economic Review, Papers and Proceedings. 69 May. Baumol, W.J. (1952). The Transactions Demand for Cash: An Inventory – Theoretic Approach. Quarterly Journal of Economics. No. 66. Darity, W. & Young, W. (1995). ISLM: An Inquest. History of Political Economy, Nov. 27. Galbraith, J.K. (1972). The Great Crash 1929. Pengium Books Ltd., Hurmondsworth. Hammond, J.D. (1996). Theory and Measurement: Causality Issues in Milton Friedman’s Monetary Economics. Cambridge University Press. Hansen, A.H. (1953). A Guide to Keynes, New York: McGraw – Hill. Harris, M. & Holmstrom, B. (1983). Macroeconomic Developments and Macroeconomics. American Economic Review, Papers and Proceedings. 73: 223 – 27. Hicks, J.R. (1937). Mr. Keynes and the Classics: A suggested Interpretation. Econometrics. 5: 147–159. King, R.G (1982). Monetary Policy and the Information content of Prices. Journal of Political Economy. 90: 247 – 79. King, R.G. (1983). Monetary Policy and the Information Content of Prices. Journal of Monetary Economics. 12: 199 – 234. Kydland, F.E. & Prescott, E.C. (1977). Rules Rather than Discretion: The Inconsistency of Optimal Paths. Journal of Political Economy. 85: 473– 492. 7 Laidler, D.E.W. (1981). Monetarism: An Interpretation and An Assessment. Economic Journal. 91:1–28. Laidler, O.E.W (1993). The Demand for Money: theories, Evidence and problems, 4th Edition, New York: Harper Collins. Lipsey, R.G. (1960). The Relationship between Unemployment and the Rate of Change of Money Wage Rates in the UK 1862 – 1957: A Further Aanlysis. Economica. 27:1–31. Lucas, Jr. R. E. (1980). Method and problems in 1978 Business Cycle Theory. Journal of Money, Credit and Banking: 7(4) Part 2: 696 – 715. Lucas, Jr., R. E (1973). Some International Evidence on Output Inflation Tradeoffs. American Economic Review. 63(3): 326 – 334. Lucas, Jr., R. E (1976). Economic Policy Evaluation: A critique, in Brunner, K. & Melzer, A.H. (eds) the Philips Curve and Labour Markets. Journal of Monetary Economics, Supplement. 1(Apr):19 – 46. Lucas, Jr., R.E. (1972). Expectations and the Neutrality of Money. Journal of Economic Theory. 4 :103 – 124. Okun, A.M. (1980). Rational – Expectations – with – Misperceptions As a Theory of the Business Cycle. Journal of Money, Credit and Banking. 12(4 Part 2):817 – 825. Santomero, A.M. & Seater (1978). The Inflation – Unemployment Tradeoffs: A Critique of the Literature. Journal of Economic Literature. June. Sargent, T. J and Wallace, N (1976). Rational Expectations and the Theory of Economic policy. Journal of Monetary Economics. 2(4):169 – 84. Sargent, T. J. (1976a). A Classical Macroeconomic Model of the United States. Journal of Political Economy. 84(4):207 – 237. Sargent, T.J. & Wallace, N. (1973). Rational Expectations and the Dynamic of Hyperinflation. International Economic Review. 14: 328 – 50. Sargent, T.J. & Wallace, N. (1975). Rational Expectations, the Optimal Monetary Instrument and the Optimal Money Supply Rule. Journal of Political Economy. 83:241 –55. Sargent, T.J. (1972). Rational Expectations and the Term Structure of Interest Rates. Journal of Money, Credit and Banking. 4:74 – 79. Shiller, R.J. (1978). Rational Expectations and the Dynamic Structure of Macroeconomic Models: A critical Review. Journal of Monetary Economic. 4(1):1–44. 8 Tobin, J. (1958). The interest, Elasticity of the Transactions Demand for Cash. Review of Economic and Statistics. 28:241 – 247. Turnovsky, S.J. (1980). The Choice of Monetary Instrument Under Alternative Forms of Price Expectations. The Manchester School. 45:39 – 63. Weiss, L. (1980). The Role for Active Monetary Policy in a Rational Expectations Model. Journal of Political Economy. 88:221 – 233. Willies, W.H. (1981). Rational Expectations, as a Counterrevolution in Bell, D. and Kristol, I (eds) The Crisis in Economic Theory, Basic Books, Inc. Publishers, New York, 81 – 96. 9