Institutional Investors & Sell-Side Analysts in Emerging Markets

advertisement

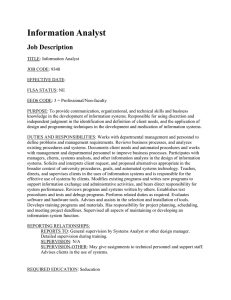

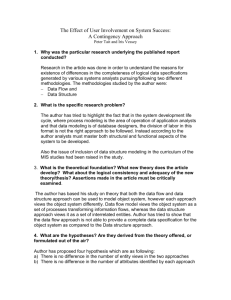

The current issue and full text archive of this journal is available on Emerald Insight at: https://www.emerald.com/insight/1755-4179.htm Inside the black box of institutional investors in an emerging market: the role of sell side analyst outputs Arit Chaudhury Institute of Management Technology Ghaziabad, Ghaziabad, India Role of sell side analyst outputs Received 25 May 2021 Revised 6 November 2021 Accepted 21 February 2022 Seshadev Sahoo Indian Institute of Management Lucknow, Lucknow, India, and Varun Dawar Department of Financial Studies (DFS), University of Delhi, New Delhi, India Abstract Purpose – In the backdrop of emerging market setting of India, this study aims to attempt to identify how Institutional investors use sell side analyst outputs for their decision-making processes in light of inherent biases in their forecasts and recommendations. The study also conceptualizes the role of internal buy side teams in the process and try to figure out the key attributes and services provided by sell side analysts, which provide maximum value to the investors. Design/methodology/approach – The study is centered upon in-depth semi-structured interviews of ten institutional investors from top Indian asset management companies covering a wide range of topics tied back to theoretical explanations. The data collected was transcribed, coded and analyzed using content analysis to ensure a systematic synthesis of point of view. Findings – The findings show that internal analyst teams of institutional investors play a dominant role in terms of validation of sell side analysts’ outputs (given the inherent biases in sell side analyst forecasts). Further, the engagement of sell side analysts by the investors are determined not only through profitable recommendations but also on the basis of soundness of the investment rationale along with other services provided. Finally, this study puts into perspective, the critical role of analyst industry knowledge and access to company management (as opposed to analyst pedigree and forecast accuracy) for institutional investors decision-making. Practical implications – The findings of the paper have profound implications for various stakeholders such as companies, sell side analysts, policy makers, researchers and students of finance in terms of detailed understanding of investment processes of institutional investors in the context of emerging markets like India, which have a different legal and regulatory set-up compared to developed markets. The authors also provide a critical perspective through an intriguing paradox that exists between finance theory and its relevance for actual practitioners. Originality/value – To the best of the authors’ knowledge, this is the first study in India which look inside the “black box” of institutional investors and their decision-making process, especially with respect to how they use sell side outputs. Keywords Institutional investors, Sell side analysts, Investment process, Interviews, Emerging market, Semi-structured interview Paper type Research paper 1. Introduction The goal of this paper is to investigate how institutional investors consider sell side outputs in their investment decision-making process. Institutional investors in the context of Qualitative Research in Financial Markets © Emerald Publishing Limited 1755-4179 DOI 10.1108/QRFM-05-2021-0086 QRFM investment management generally refer to asset management companies such as mutual funds, insurance companies, family offices and wealth management services. Over the past decade, development of the capital markets has led to yield hungry investors to shift large portion of their money from traditional asset classes (such as savings deposits, gold and real estate) to various active and passive funds (primarily invested across equity and debt) run by professional fund managers. Global assets under management (AUM) are expected to rise from US$111tn in 2020 to US$145tn in 2025 [1], while the industry AUM in India rose to INR 31.4tn at the end of March 2021 compared to INR 10tn in May 2014 [2]. With such an increasing prominence of institutional investors, understanding of their investment processes and how they use various outputs like those from the sell side in their decisionmaking process, becomes an addressable issue for researchers and regulators. However, research concerning the investment decision process of institutional investors have been sparse, especially in the context of how they use sell side analyst outputs, thereby raising a valid question on the context within which they make decisions. Much of the research on sell side outputs have been empirical in nature and generally focused upon analyst forecasts neglecting the overall value they provide to the institutional investors. Consequently, there is a lack of understanding on how institutional investors arrive at their investment decisions and what is the role of sell side analysts in that process. The primary business model of the sell side is to provide data-driven outputs and investment advisory to the institutional investors who pay them brokerage for the trades executed and occasionally, pay direct soft dollars for their advice and outputs. They communicate their expertise and understanding of the business through regular research reports on the companies under their coverage. One of the key outputs on the basis of which sell side analysts are assessed are the earnings forecasts and their accuracy. Most of the literature on sell side analysts focuses on empirical studies based on archival analyst forecast data as it is less costly than carrying out an experiment or content analysis of equity research reports (Bradshaw, 2011). However, there are other important functions that the sell side analysts perform. Earnings forecasts are means to an end rather than an end in themselves and analysts provide other services like “industry knowledge” and “management access”, which are more valuable to investors than just the forecasts (Brown et al., 2016). Empirical studies on analyst forecasts, at best, provide an association between the forecasts and various financial parameters, analyst characteristics or market price behavior, but do not address the question of whether the forecasts are actually useful to the investors. There is also little work on how investors perceive analyst forecasts and use them for their investment decision-making process. Sell side analyst forecasts are known to be biased due to various reasons ranging from cognitive biases (Dreman and Berry, 2006) and willingness to cultivate good management relations (Francis and Philbrick, 2006; Lim, 2001; Richardson et al., 2004; Ke and Yu, 2006). In light of the biases inherent in sell side analyst outputs, it is imperative that institutional investors do not take them at face value without validating. All institutional investors have an internal team of buy side analysts who follow a detailed process and come up with their own investment views, which might or might not be in line with sell side recommendations. To understand this internal process better, we need to adopt alternative approaches like surveys and interviews which are expected to provide more useful insights (Bradshaw, 2011). We also, could not find any research on how sell side research reports, which contain detailed explanation of the analysts’ views along with all the forecasts, recommendations and target prices, are useful to institutional investors. There are only few studies in literature like Asquith et al. (2005) who perform content analysis of analyst research reports. This is a surprising gap in literature as research reports contain full descriptions of the investment thesis along with all the analyst outputs in one place, which can be used as an initial input by investors in their decision process. Through semi-structured interviews of institutional analysts and fund managers, we try to map the process of how research reports along with other outputs and analyst calls are used to make investment decisions and engage with the sell side analysts (Figure 1). Moreover, we argue that much of the past research done on the subject is generally limited to developed markets (US, UK) with very little evidence on developing or emerging markets, which are characterized by poor investor protections and legal enforcements. We believe cross country differences and level of sophistication of financial markets and investors require a concerted study on emerging market such as India to develop an in-depth understanding of fund management processes. In response to the above research gap, this study attempts to penetrate the black box of institutional investors’ investment decision-making, especially on how they use sell side analyst reports, earnings forecasts and other services provided by them. In fact, till now no study to the best of our knowledge, has examined these issues in the context of emerging market of India. The qualitative orientation of this study as opposed to quantitative orientation in extant literature enables cutting edge insights into above issues with respect to investment decision-making. Our study contributes to the existing literature in several ways. First, while prior studies in the extant literature do shed light on activities of investment analysts (Cheng et al., 2006; Middleton et al., 2007; Drachter et al., 2007; Imam and Spence, 2016; Coleman, 2014; Brown et al., 2016), determinants of their investment decisions and practices followed are still unclear, particularly from the perspective of emerging markets like India where institutional settings, information flows and corporate governance standards are quite different from those in developed markets (such as USA, UK, Canada). Our extensive field study thus represents an important contribution to the existing literature in terms of providing useful insights to global investors and policymakers into rationales and mechanisms being currently followed in investment decision-making by fund managers, using sell side analyst outputs, in an emerging market setting. Sell side equity research report sent to instuonal investors. Main contents: • • • • Investment thesis Earnings forecasts Recommendaon (Buy/Sell Hold) Target price Step 1: Step 2: Meeng/telephonic discussion of sell side analysts with fund managers/buy side analysts to discuss the investment thesis and financial. Internal discussion among fund management team regarding sell side analyst outputs. Key aspects: • • Yes Role of sell side analyst outputs Convicon in arguments. Past performance of recommendaons and error in forecasts. Step 5: Connue further engagement Yes • • Was the basis of recommendaon sll sound? Does the analyst provide good management access and other services? No Step 5: Disconnue engagement Step 3: No • Was the investment decision profitable? Step 4: Make an investment decision: To buy or sell • Independent evaluaon by buy side analyst team. Management conference calls and or calls with other stakeholders to gain further comfort. Figure 1. How institutional investors engage with and evaluate sell side analysts QRFM Second, we argue that while sell side analysts, can at times, get away with adverse stock recommendations results by citing risk factors on their reports, no such leeway is available to institutional analysts and fund managers’ who are constantly expected to perform or perish. In an environment fogged with uncertainty and pressure to perform, investment decision-making becomes a challenging task, particularly, in emerging markets like India where information asymmetry impedes the ability of fund managers to constantly outperform their benchmarks. Consequently, institutional analysts have strong incentives to identify the analyst attributes and the type of analyst services required within challenging time constraints to meet their goals. Our study identifies the pecking order of such dominant services and the most desirable attributes of sell side analysts, which create value for investors thereby bringing important insights to literature from an emerging market perspective. To undertake our study, we conduct semi-structured interviews on wide range of topics with Fund Managers and Sector Analysts representing Top Indian Asset Management Companies (primarily Mutual Funds, Insurance Companies, Family offices and Wealth Management Firms) between September 2019 and January 2020. The findings of our study put into perspective, how investors evaluate sell side analyst outputs, given the inherent bias in them due to various reasons ranging from cognitive to strategic. The rest of the paper is organized in the following way. Section 2 discusses the literature review; Section 3 describes the research design; Section 4 details the sample selection; Section 5 reports the findings of the interviews conducted; Section 6 summarizes the discussion and Section 7 concludes with implications. 2. Literature review Research on financial analysts have disproportionately focused on empirical analysis of analyst forecast data as it is easily available in databases. Sell side analysts not only provide forecasts for company financials but also investment advice for buy-side clients in form of a recommendation often accompanied by a target price (Bradshaw, 2011). However, the key question is of the reliability of sell side outputs as analysts could suffer from various sources of bias as well as various conflicts of interest. Forecast accuracy and bias are affected by the analyst incentives, their skill levels as well as complexities in their job (Kothari et al., 2016). It has been established in literature that analyst forecasts are generally optimistic (De Bondt and Thaler, 1990; Ali et al., 1992; Frankel and Lee, 1998; Easton and Sommers, 2007). This could be attributed to several reasons like cognitive biases (Dreman and Berry, 2006), analyst self-selection (McNichols and O’Brien, 1997), good management relations (Francis and Philbrick, 2006; Lim, 2001; Richardson et al., 2004; Ke and Yu, 2006), equity offerings (Dechow et al., 2000) and alternate communication channels (Berger et al., 2019). On the other hand, there are also papers exploring the under-reaction of analysts (Mendenhall, 1991; Abarbanell and Bernard, 1992). Easterwood and Nutt (1999) suggest that analysts underreact to negative information and overreact to positive information. In some recent studies, Chang and Hao (2020) show that analysts have a pessimistic bias depending on relative income growth. Forecast bias could also arise from financial items like intangible intensity (Ferrer et al., 2020), discontinued operations (Beyer et al., 2021) or even the difference between pre-tax book income and taxable income (Choi et al., 2020). To deal with these biases, institutional investors do not take the sell side outputs at face value but have their own internal buy side teams to carry out an independent analysis. However, research on performance of buy side analysts are not as prolific as those for the sell side, as information about buy side research is most private. Buy side analysts have different sources of information and scope of work compared to the sell side analysts (Groysberg et al., 2007). Fund managers put more weight on reports by the internal buy side analysts when the bias of the sell side analyst increases (Cheng et al., 2006). There have been also been some studies comparing the performance of buy side analysts with those of sell side analysts. Cheng et al. (2006) find that that sell side analysts are more biased and optimistic compared to buy side analysts. However, Groysberg et al. (2007) and Hobbs and Singh (2015) find that sell side analysts provide superior recommendations compared to buy side analysts. Thus, it is clear that buy side analysts perform a different role compared those from the sell side and add value to fund managers in their internal decision-making process. But there is a gap in literature in understanding how buy side analysts take sell side outputs into account while making their recommendations. To understand the investment process followed by buy side institutional investors, rather than empirical studies, alternate research methods like surveys and experimental studies are more useful and picking up gradually (Bradshaw, 2011). Majority of the studies on the investment decision-making process has concentrated on analysts and fund managers in developed markets (Belkaoui et al., 1977; Arnold and Moizer, 1984; Pike et al., 1993; Barker, 1998; Middleton et al., 2007; Drachter et al., 2007; Imam and Spence, 2016; Coleman, 2014 among others) with limited evidence in emerging markets. While a plethora of studies has used surveys to capture the decision-making practices of investors (Arnold and Moizer, 1984; Pike et al., 1993; Lai et al., 2001; Drachter et al., 2007 among others), other studies relied on interview technique (Holland and Doran, 1998; Holland, 2006; Henningsson, 2009; Tuckett, 2012; Coleman, 2014; Foster and Warren, 2016) as it tends to provide a comprehensive and richer insight into observed behavior that may be difficult to gauge through survey responses or any quantitative methodologies. In one of the earlier works on investment decision-making processes, Arnold and Moizer (1984) conduct a comprehensive survey of 505 UK investment analysts between the years 1978 and 1981 to understand the valuation techniques, forecast methods used and sources of information. They found that while analysts accorded perceived importance to annual profit and loss statement, balance sheet and interim results, discussions with the company management turned out to be a significant source of information. In the same vein, Pike et al. (1993) investigated the investment processes through surveys of UK and German analysts and found that there was little change in share evaluation techniques over the past decade despite introduction of new technologies and increasing market efficiency. Second, the study reported that German analysts pay more attention to new non-financial company information specifically related to research and development or product quality nature compared to their UK counterparts. Drachter et al. (2007) tries to assess the behavior and attitudes of German mutual fund managers using a telephonic survey. The results indicate that the fund managers’ behaviors vary considerably with the characteristics of the funds and the characteristics of the fund company. While larger funds considered conversations with company executives to be an integral part of fund management process, smaller funds tend to be divided in their importance to conversations with company management. Likewise, a number of studies have been conducted based on interviews with investors in developed markets. For example, Holland and Doran (1998) in their study interviewed 27 of the largest UK financial institutions to understand influence advantage from the relationship with the investee companies in their portfolio. The results of the study showed that relationship information helped stock valuation and portfolio decisions irrespective of the valuation method used. Lai et al. (2001) also examined the investment practices and processes of 77 Malaysian institutional investors during bullish and bearish periods and concluded that investors relied mainly on fundamental analysis (complemented by technical analysis) to make investment decisions during both bullish and bearish periods. Role of sell side analyst outputs QRFM Holland (2006) again in a study conducted interviews of 40 fund managers representing 35 of the largest UK funds for the period between October 1997 and January 2000 find that fund managers generally resorted to private meetings with company management to understand value of intellectual capital and intangibles while valuing the companies. Coleman (2014) conducted semi-structured, interviews with 34 fund managers across Istanbul, London, Melbourne and New York. The key findings indicated a preference for qualitative analysis, attitudes, heuristics and social networks over conventional quantitative data and analysis. In the emerging markets context, most studies are based on investment decisions of retail investors, more on the investment tools and less on the process. Mohamad and Perry (2015) try to develop a framework for investment processes followed by fund managers in Malaysia. Jaiyeoba et al. (2018) survey four retail and four institutional investors in Malaysia and try to understand their company selection processes and investment decision challenges. The country governance factors, which affects earnings efficiency, might also play an important role in an emerging markets context (Kamarudin et al., 2014, 2016). However, we could not find any study which looks at how institutional investors in emerging markets use sell side outputs in their decision-making. Brown et al. (2016) carried out a survey of 344 buy-side analysts from 181 investment firms in developed markets and found that “industry knowledge” and “access to company management” are the most important services to the investors provided by the sell side. However, it does not deal with how internal buy side teams consider sell side outputs and how they are used to engage with the sell side analysts. Most of the previous studies focus on the empirical properties of sell side analyst forecasts, while research on how buy side investors actually use these and other sell-side outputs in their actual investment processes, present a significant gap. Qualitative studies on the processes followed by institutional investors, especially in the context of emerging markets like India, which have a different legal and governance framework compared to developed markets, are also few and far between. Our work explores these questions in greater depth on how sell side outputs are used by institutional investors, what role is played by buy side analysts in the process, and finally, what are the key sell side services and attributes which provide maximum value to institutional investors, particularly in the emerging market context of India. 3. Research design While the extant literature specifies a plethora of methods for data collection such as indepth interviews, observations, surveys and document review Marshall and Rossman (2011), this study uses an semi-structured interview-based approach to achieve the objectives concerning how institutional investors use sell side outputs for their decisions. In this case, the study conducts in-depth semi-structured interviews motivated by grounded theory approach (Strauss and Corbin, 1990; Glaser, 1992). In following this approach, we tend to examine the subjects in a natural setting and then interpret the gathered field notes, conversations, meanings and actions. Semi-structured interviews lie between the continuum of unstructured and structured interviews. While unstructured interviews are generally interview and context specific, structured interviews involves a series of pre-established questions to be answered by the interviewee. In between them, semi-structured interview set up involves questioning based on interview guides containing identified themes to elicit detailed responses in a systematic manner and at the same time allowing interviewee to command flexibility in responding the way they like. According to Qu and Dumay (2011), semi-structured interviews are a popular method of qualitative research, which contains guided questions which helps direct the conversation toward the themes the interviewer wants to investigate. It is also flexible, accessible and intelligible and, more important, capable of disclosing important and often hidden facets of human and organizational behavior. Similarly Kvale and Brinkmann (2009) in their study observe that semi-structured interview is the most effective and convenient means of gathering information. For our study, we develop an interview guide with respect to investment practices and determinants of stock recommendations of institutional investors. Our interview guide contains the following sequence of guided questions to the institutional investors to direct the conversation around certain chosen themes. They were structured in line with the following research questions (RQs): RQ1. How important for you are sell side analyst outputs and their earnings forecasts? RQ2. How do you use various sell side outputs to arrive at your investment decisions? RQ3. How do you decide to evaluate and engage with the sell side analysts? RQ4. What role does the internal buy side analyst play compared to the sell side analysts? RQ5. Which are the most important attributes of a sell side analyst? RQ6. Which activity of the sell side analyst provides most value to your investment process? The questions pertaining to above sequence of topics were open ended in nature to allow respondents to express themselves in their own way. The interviews went on for approximately one hour each with each interviewee being provided with same set of questions. The data collected from the interviews were transcribed, coded (Glaser, 1992) and analyzed using content analysis wherein the dominant messages, themes, viewpoints and facts within the text were duly identified. This ensured a systematic analysis of the responses of the interviewees and their support for a particular point of view. Post this systematic analysis, findings were formalized giving detailed insights into investment decision-making processes and viewpoints of interviewees. To ensure integrity of our qualitative research, the interview data was diligently verified with written notes and documents for confirmation on accuracy. 4. Sampling 4.1 Sample selection and characteristics The study is based on semi-structured interviews with a sample comprising fund managers representing leading Indian institutional investors from some of the top mutual funds, insurance companies, family offices and wealth management firms in India. A total of 10 interviews were conducted with professionals who control funds with AUM (assets under management) ranging from $300m to $4bn, all in leadership or key decision-making roles. The interviewees were selected through recommendations from investment consultants, referrals as well as professional contacts of the co-authors. There were a total of 9 male and 1 female participants, with an investment experience of between 15 and 25 years with all the participants having a professional qualification of MBA, CA or CFA. The approach was that of a guided semi-structured interview, in which participants were given the assurance of confidentiality to understand how the institutional fund managers perceive sell side analysts and use their outputs. This allowed the participants to provide their own insights and additional information around the various themes and allowed deeper exploration of their decision-making process (Hermanson et al., 2012; Coleman, 2014). Role of sell side analyst outputs QRFM The sample of 10 interviewees is admittedly small compared to the universe of domestic institutional investors who invest in the Indian markets (a total of 41 mutual funds, 24 life and 33 general insurance companies, and several family offices and wealth management firms as of 2021). However, after conducting about 6–7 interviews, we found that we found little additional insights on the themes of our interest and reached the point of diminishing returns (Hermanson et al., 2012). Also, according to Malterud et al. (2016) and Jaiyeoba and Haron (2016), a sample of 6 to 10 participants may be sufficient in an interview based study if the aim is suitably narrow, participants are more specific to the research question and analysis involves longitudinal in-depth exploration. We believe our sample size of 10 was sufficient enough to validate conclusions as saturation was reached on key issues with additional interviews unlikely to yield any new information (Guest et al., 2006). One drawback of our process is that the sample could be biased since it was based on self-selection of the co-authors. But this aspect was more or less mitigated since all the participants were senior practitioners, in leadership roles with a minimum experience of 15 years, and thus provided many meaningful insights in the setting of a free-wheeling discussion. Table 1 provides background information and key characteristics of our sample. 5. Findings Following the research design section wherein interview data was collected, transcribed, coded and mapped into themes, this section discusses the broad findings of the study conducted. The analysis of the data revealed the following summary findings based on Type of employer Table 1. Characteristics of interviewees No. Mutual fund 3 Insurance 3 Family office 2 Wealth management 2 Assets under management (US$m) % of sample upto 500 30% between 500 and 1000 30% between 1000 and 2500 20% > 2500 20% Size of investment team members % of sample 1-3 20% 3-5 20% 5-10 40% >10 20% Gender % of sample Male 90% Female 10% Educational qualifications % of sample (including dual qualifications) MBA 80% Masters in Finance 20% CA 30% CFA 30% Job experience (mean years) 16 20.33 19.5 19 Notes: MBA – Masters in Business Administration, CA – Chartered Accountant, CFA – Chartered Financial Analyst collating the responses from the interviewees and arranging them in line of the research questions identified above: RQ1. How important for you are sell side analyst outputs and their earnings forecasts? Most respondents agree that sell side analyst outputs, specifically earnings per share (EPS) forecasts are something that they consider while researching a company for investment. One key takeaway from our unstructured interviews is that analyst forecasts and other outputs act only as a preliminary check before the internal team does their own analysis. Hence, the investors do not take the sell side outputs at face value. Also, rather than on a regular basis, analyst outputs are more useful when a new company is being analyzed. Analyst forecasts act as a guide, when institutional investors are researching a new investment idea for which they use sell side views as an initial guidance: When investigating a new company, rather than starting from scratch, our internal team considers the sell side forecasts as an initial indication of the worthiness of the idea – Fund manager, insurance company However, analyst EPS forecasts are not the only thing that helps them form an investment idea. The recommendation and target price also plays an important role in validating the forecast: Along with earnings forecasts, the upside in the target price and the strength of recommendations also tells us about the conviction of the sell side analyst – Head (investments), family office Individual sell side analyst forecasts are also useful to compare the divergence from consensus. A few respondents reported specifically picking up those analyst outputs, which vary from the consensus. This often allows new insights that might have been missed by the consensus: Analyst outputs are more useful if they differ from the crowd. We pay more attention to those forecasts which vary from consensus. We look at the numbers and investment rationale more closely in those cases – Partner, wealth management We pay more attention to analyst views which disagree with us, rather than those who agree – Senior fund manager, insurance company Another important issue was the possible bias in analyst forecasts due to the fact that their reports are public, and they need to cultivate good management relations to retain accessibility. Institutions are aware of this fact and thus prefer independent sell side houses or avoid sell side analysts involved in recent deals: We seek an independent and unbiased view from analysts, which, understandably might not be always possible due to various reasons. No one blindly trusts analyst forecasts and recommendations without verifying their rationale. We prefer to work with independent brokerages, but there are few such firms in India – Director, wealth management. To summarize, institutional investors agree that sell side analyst outputs are an important tool to evaluate investment ideas. However, they use it to further validate their own ideas and not as a direct investment tool, as there could be various sources of bias. Different analyst forecasts are compared and analyzed by the internal buy side teams which carry out their independent analysis: RQ2. How do you use various sell side outputs to arrive at your investment decisions? Role of sell side analyst outputs QRFM Even though earnings estimates of sell side analysts are the most widely tracked, a sell side analyst provides views on several other variables such as stock recommendations, growth projections, target prices and also other qualitative factors (Bradshaw, 2011). All these variables are captured in the analyst research reports, which are distributed to the institutional investors in return for future trading brokerage and, sometimes, soft dollars. Analyst reports are also of different types. There are recurring reports covering quarterly results and upgrades/downgrades. There are also initiating coverage reports which contain the detailed investment thesis when the company is brought under coverage the first time. We asked our interviewees how useful are these research reports to make their investment decisions: Sell side analysts generally cover companies in great depth in their reports along with the full investment thesis and financial forecasts when they initiate coverage. It is very useful to know about a company in depth – Fund manager, mutual fund Sell side analysts, after publishing their reports, often follow up with the investors with a client call, explaining their investment thesis, forecasts and recommendations. This is partly because it is not possible for institutional investors to go through all sell side reports in detail. This is also useful for investors to understand the report better as well as form an internal view about the investment. However, what came out from our conversations, was that a call or meeting with the sell side analyst to discuss his/her report often provides new or even critical insights which might not be present within the report itself. This could also be important, due to various inherent bias in analyst outputs, as discussed earlier, which might necessitate direct interactions to examine the validity of those outputs (Berger et al., 2019): A call or meeting with the sell side analyst is often necessary to understand and validate the key points discussed in his/her research report and to test the analyst’s conviction. A research report could be biased since the analyst cannot write unflattering words about the company in an open document. They are more forthcoming in a direct conversation – Director, wealth management Thus, the value provided by the sell side does not only end at sharing earnings forecasts and recommendations but also explanation of their investment arguments on basis of which the institutional investors’ internal team can take a decision. Finally, we found that sell side analysts provide additional services to the institutional clients by also setting up management meetings, conferences and investment seminars: Interaction with the company management is very important to understand the business outlook, the future growth trajectory and also get more detailed business insights. It also helps in validating the sell side story. This is more important for new companies rather than companies we already know about. – Fund manager, insurance company RQ3. How do you decide to evaluate and engage with the sell side analysts? We tried to understand the process by which the institutional investors engage with and give business to the sell side analysts. This also allowed us to create a process map of their activities and how they are linked to the evaluation of sell side analysts (Figure 1). The discussions with the sell side analysts based on their reports and follow up calls/ meetings also serve an important purpose in evaluating them for future brokerage business. As there could be several sell side analysts who are servicing a client, investors often create a pecking order of top analysts with whom they interact with more closely and provide more business: There are dozens of brokerages and it is not possible for us to entertain each and every analyst. We create a list of high performing analysts whose advice we pay close attention to. Most of our brokerage business is distributed among the top 5-10 sell side houses based on analyst performance – Senior fund manager, mutual fund The engagement of sell side analysts are based on quality of their advice and profitability of their recommendations. Once a sell side report is released and discussion with the analyst is completed, there is a deliberation within the internal team to discuss the idea. The internal discussions critically evaluate the strength of the sell side analysts’ investment arguments and financial forecasts, as well as their past track records and forecast errors. It is often followed by more primary research and management interactions which the sell side analysts help set up: What determines the usefulness of the sell side analysts are not only the hard outputs but also services like access to management and also other stakeholders and industry bodies. It helps us form an independent view about the company if we decide to invest – CIO, family office After evaluating the analyst reports, internal team discussions as well as management meetings, the institutional investors arrive at a decision on whether to invest in the company. One of the main parameters in evaluating the sell side analyst is definitely the performance of the recommendations. However, we find that even if the recommendation turns out not to be profitable, institutional investors can continue engagement with sell side analysts if their recommendations were based on a strong rationale: We understand that markets don’t always react the way we expect and same with company forecasts. However, if a sell side analyst’s views were based on a strong investment argument and rationale, even if the market moves against it, we see no reason in penalizing him/her. An analyst also provides other useful services – Senior fund manager, mutual fund Based on our discussions with several investors, we mapped the investment process of the institutional investors and how they engage with the sell side analysts (Figure 1). The sell side analyst outputs are discussed, evaluated and scrutinized by the internal team, backed up with calls and meetings both with the analyst and company management, before an investment decision is taken. Performance of the recommendations, investment rationale and others types of services provided decide the engagement level with the analysts: RQ4. What role does the internal buy side analyst play compared to the sell side analysts? Every large institutional investor has an internal buy side investment team comprising of analysts, fund managers and dealers working under a research head or Chief Investment Officer. The main question we wanted clarity on is that how the role of the internal buy side analyst differs from that of the sell side. The buy side investment team of an institutional investor often contains a small team of research analysts compared to a dedicated analyst for each sector in the sell side. Thus buy side analysts vary significantly in scope and coverage of companies compared to the sell side (Grosberg et al., 2007). Sell side analysts also have a deeper understanding since they cover less number of companies compared to the buy side (Brown et al., 2016). The main difference is in the composition of the team where sell side analysts cover companies sectorwise, while a buy side analyst can cover companies across multiple sectors: We have a team of 5 analysts covering more than 100 companies and multiple sectors between them. Whereas the average sell side house has a team of at least 20 based on sectors under Role of sell side analyst outputs QRFM coverage. Definitely the sell side analysts have a deeper knowledge base since they are sector specialists – Senior fund manager, Insurance company However, this does not mean that the job of a buy side analyst is “shallower” compared to that of the sell side. While a sell side analyst is evaluated not just on their financial forecasts and recommendations but also on factors such as industry knowledge and management connect, a buy side analysts’ performance depends only their profitable recommendations, which results in a positive “alpha [3]” to the fund. This means that buy side analysts have more stake in their decisions and have their “neck in the line”. This is particularly true for mutual funds for whom fund performance even in the short term is key to continuing business: This is a competitive industry which places emphasis only on NAV [4] performance. A buy side analyst clearly has his task cut out. Repeated wrong calls would is not something which is acceptable – Fund manager, mutual fund The increased stake in investment recommendations for a buy side analyst means that every decision has to be carefully evaluated and analyzed from different angles before taking a final call. Hence, the buy side analysts play an important role in scrutinizing the forecasts and recommendations of the sell side analysts to zero in on a decision: Our internal analyst team meets with different sell side analysts, scrutinizes their investment thesis, financial forecasts and often meet the management before taking a final call. Thus, our analysts aggregate the views of various stakeholders before taking an independent call based on their own judgment, for which they are accountable – CIO, family office This is particularly important, as a sell side analyst could suffer from several sources of bias which is explored in depth in literature, starting from cognitive biases (Dreman and Berry, 2006) to willingness for good management relations (Francis and Philbrick, 2006; Lim, 2001; Richardson et al., 2004; Ke and Yu, 2006): A sell side analyst has different biases and conflicts of interest due to business reasons because of which their forecasts and recommendations cannot be taken at face value. Our internal analyst team can take more unbiased calls – Senior fund manager, insurance company Thus, we find that buy side analysts play an important role in validating the views of the sell side analyst and mitigating the bias in their outputs and make their own independent judgment on the investments. The stakes are also higher for a buy side analyst: RQ5. Which are the most important attributes of a sell side analyst? As institutional investors deal with several sell side analysts, we seek to better understand which qualities of an analyst provide maximum value to them. We asked the interviewees about the attributes that are used by them to rank and evaluate the sell side analysts to decide the level of engagement with them. They were asked to rank the attributes of a sell side analyst on a 0 to 5 scale, with 5 being the most important and 0 being the least. Each attribute is scored independently. The average scores are then compared to rank the attributes in order of importance (Table 2). Our interviews highlighted on the importance of industry knowledge of sell side analysts as a top attribute in terms of usefulness to institutional investors (Table 2). In fact, this observation underscored an important theme related to engagement of sell side analysts. Most of our interviewees’ stressed upon the role of previous industry experience of sell side analyst, in fact someone who has worked previously in a particular industry was perceived to be more useful than others with no industry experience. There was a widespread belief that sell side analysts with past specialized industry experience are better equipped to understand industry dynamics and deal with management rhetoric: Sell side analysts with past stints in the industry are rated highly by us particularly for specialized sectors like Pharma or Oil and Gas. We prefer to interact with analysts who have worked in that industry, they give us a more grounded view of the industry dynamics and company’s competitive positioning. – Partner, wealth management Role of sell side analyst outputs The second most attribute of an analyst was “accessibility and quick response”. We found that it is important for the sell side analysts to be responsive to calls and requests of institutional investors. This is because investors have to act within a limited time period when opportunities are present and hence timely advice from sell side analysts is critical: We often need the sell side analysts to quickly crunch some numbers for us since opportunities in the markets are short lived. So prefer to work with analysts who are fast and accessible to allow us to quickly take decisions – Fund manager, mutual fund Surprisingly, personal compatibility came out to be the third more important attribute desired by institutional investors. Though this does not necessarily mean favoritism, a sense of camaraderie clearly has a role to play: We prefer to work with good sell side analysts with whom we are comfortable – Head (investments), family office However, the years of work experience does not matter as much as industry knowledge and was ranked fourth among six attributes (Table 2). It is clear that more years of experience is not necessarily a highly desired attribute and also, being more experienced might not correlate with higher industry knowledge. Analyst rankings (Institutional Investor/Asiamoney, etc.) or pedigree (big or small brokerage) are not given any importance by the institutional investors. This means that investors carry out their own independent evaluation of sell side analysts and do not rely on external attributes. Surprisingly, we found that analysts from smaller houses can in fact be more useful than the more pedigreed ones: We evaluate sell side analysts based on the value they create for us and not on where they work. Some analysts from smaller brokerages cover more small and micro market capitalization companies which are more useful to us. Bigger companies are anyway well researched – Senior fund manager, insurance company Finally, hard skills of an analyst like analytical and communication skills do not appear to play a role, since, at this level, such skills are not such an important differentiator: Sell side analyst attributes Industry knowledge Accessibility and quick response Personal compatibility Years of work experience Analytical and communication skills Ranking/pedigree Average score in terms of usefulness for investment decisions 4.7 4.5 4 3 1.9 1.8 Note: The above ranking is based on average scores (0–5) based on importance by the interviewees for each analyst attribute. Every attribute is scored independently Table 2. Sell side analyst attributes QRFM RQ6. Which services of the sell side analyst provides most value to your investment decisions? Along with the individual analyst attributes, the kind of services provided by the sell side is an important parameter for engagement. This is because even if a sell side analyst has some highly desirable attributes, the client policies and infrastructure provided by brokerages also play an important role ensuring quality of service. We tried drafting a perceived ranking order of sell side services from the point of usefulness to investment decisionmaking by questioning the institutional investors (Table 3). Our interactions clearly suggest “access to company management” as the most useful service input for decision-making process of institutional investors (Table 3). Our interviewees stressed upon the fact that given the large number of companies they cover, it becomes virtually impossible to build relations with each and every company management and therein comes the significance of sell side analysts. Sell side analysts acts as intermediaries between the company management and fund managers/sector analysts and can timely arrange meetings and conference calls: I would rate access to company management very highly while evaluating the sell side analyst. It is not possible for us to maintain so many company relationships. We depend more upon the sell side analysts’ access to management for detailed meetings and calls. – Partner, wealth management We also found that technical factors such as markets and trade information play have an important role for institutional investors, which is the second most important service (Table 3). This means that a sell side analyst has to not only provide fundamental research about the companies but also keep track of technical and trade related information. While this service is sought by all institutional investors, we found that mutual funds find this particularly important: Our industry is highly competitive. It is important to be aware of what our competitors are doing, and what they are buying and selling. We rely on the sell side to provide us fast and accurate trade information - Fund manager, mutual fund. The third factor which we found most important in the packing order is the depth of coverage universe, in other words, number of companies tracked. This tallies with what found earlier in RQ5 that coverage of smaller market capitalization companies are more useful to institutional investors, as larger companies are well researched. Clearly, here smaller brokerage houses have a niche. One more important conclusion we found is that the main hard outputs of the sell side analysts, that is, their research reports and financial models, only lie somewhere in the Sell side analyst service Table 3. Sell side analyst service usefulness Access to company management Markets and trade information Coverage universe Quality of research reports Quality of financial models Accuracy of forecasts Frequency of reports and mailers Average score in terms of usefulness for investment decisions 4.6 4.1 4.0 3.9 3.3 2.9 2.8 Note: The above ranking is based on average scores (0–5) based on usefulness by the interviewees for each kind of service. Every service is scored independently middle of the pecking order (Table 3). We found that though these outputs are important, they do not necessarily have to be very detailed: Some analysts provide more detailed research and models compared to others, but short and simple reports and models are something which we prefer. Complexity might sometimes hinder clarity – Senior fund manager, insurance company Lastly, past forecast accuracy and frequency of research reports are considered relatively less useful for investment decision-making from the perspective of institutional investors. Again, the underlying theme here is that fund managers do not much care for past forecast accuracy and are rather seemingly more concerned with value addition done by sell side analysts in terms of access to management and trade information. We do find this at odds again with tenets of academic theory wherein forecast accuracy of sell side analyst has much more research coverage than other services. 6. Discussion Through carrying out unstructured interviews of different categories of institutional investors in India, we uncover various facets of how these investors use sell side analyst outputs to drive their investment decisions. Various categories of institutional investors: mutual funds, insurance companies, wealth managers and family offices are studied through six different guided questions ranging from how important are sell side analyst outputs and how they use them, to the processes they follow in their internal teams and engagement of sell side analysts and finally what type of attributes and services are most important for sell side analysts. We find that institutional investors do pay attention to sell side outputs such as earnings forecasts and recommendations, but that solely does not influence their investment decisions, given the inherent bias in those outputs. Analyst reports and forecasts are more useful mainly for new companies or if they differ significantly from other analysts. The investors have their own internal team of buy side analysts who validate those outputs and carry out further analysis. The sell side analysts often follow-up on their reports and outputs with detailed calls with investors explaining their rationale and also set up calls with company management for the investors for further discussions. The sell side analyst outputs are also used a tool to evaluate and engage with the sell side analysts. This is important as an investor typically engages with only top 5–10 sell side analysts. However, engagement does not depend only on performance of sell side company recommendations and forecast error. As the buy side analysts deliberate and carry out their own independent assessment, the sound basis of the sell side investment rationale along with other services provided like management access also help to decide further engagement, even though profitable recommendations are important too. An important distinction that came out in our interviews were the seemingly different roles played by the buy side analysts compared to the sell side. Even though, both carry out company analysis, the sell side forecasts and recommendations could be biased due to various conflicts of interests, while the buy side analysts without any conflicts are better placed to provide their own unbiased views. The buy side analysts are also under more pressure for their investment decisions to perform well, even though sell side analysts are judged on variety of other parameters. This is particularly true for mutual funds which for whom NAV performance, even in the short term, is more critical. The buy side analysts play the role of validating the sell side outputs, have meetings with the management and carry out their own independent analysis for the investment decisions. However, the scope of the Role of sell side analyst outputs QRFM buy side analysts is broader, and they cover more companies compared to sell side analysts who are more like sector specialists (Groysberg et al., 2007). Finally, we try to rank different attributes of a sell side analyst and the types of service they provide, which provided maximum value addition to institutional investors. We find that the industry knowledge of the analysts is the most desirable attribute, followed by accessibility and responsiveness to enable decision-making. Surprisingly, compatibility with buy side analysts also plays an important role, which highlights the “human” element of these interactions. External analyst rankings and pedigree are not that important to investors (Brown et al., 2016). In types of service desired by investors, the access to company management provided by the sell side analysts is the most desirable. Surprisingly, markets and trade information, apparently non-fundamental factors, are also valued highly, particularly by mutual funds, which might be a reflection of the industry competitiveness. The analyst reports and financial models are also useful but lesser than the earlier two factors. Also, more importantly, the analyst forecast accuracy, which is one of the most prolific topics in literature on sell side analysts, do not seem to matter too much to investors! This means that researchers have been spending a lot of time on topics, which do not play a very important role for investors, while ignoring some of the more important ones. The implications of our work are for companies, sell side analysts, regulators and researchers to understand how institutional investors make their investment decisions and the role of various sell-side outputs in the same. Our study sheds light on the entire investment process as opposed to just the sell side analyst forecast, which is only one of the inputs to the process and as we found, not the most important one. A deeper understanding of the investment process is more useful for regulators, especially in an emerging markets context, to devise policies to enable greater transparency and compliance. Sell-side analysts can also use our work to understand that are the most important activities and attributes useful for institutional investors and improve their services by incorporating the same. 7. Conclusion and implications Academic research on institutional investors have generally been sparse in extant literature, raising a valid question on their decision-making processes. It is also important to further explore the role of sell side analysts in this process given the preponderance of literature on their forecasts and its empirical properties, but hardly any on the importance of their outputs to their primary clients, that is, the institutional investors. This assumes further importance for emerging markets such as India where information asymmetry and weak governance structures call for a concerted understanding of the same. In effect, till now no study has examined these issues in the contextual setting of emerging market of India. The qualitative orientation of this study as opposed to quantitative orientation in extant literature provides significant insights into what goes behind-the-scenes in terms of investment practices and how sell side analyst outputs are used in the process. Our extensive field study conducts face-to-face semi-structured interviews with senior leaders from institutional investing firms (primarily Mutual Funds, Insurance Companies, wealth managers and family offices) to penetrate the black box of investment decision-making by identifying and conceptualizing the role of sell side analyst outputs to stock investments. Our interviews touched upon the important role of sell side analysts in institutional investors’ investment decisions. We explored how sell side analyst outputs are used to take investment decisions and mapped the process of engagement of sell side analysts by the investors. We also contrasted the role of internal buy side analysts who provide more unbiased independent analysis compared to those of the sell side. The study further reports sell side analysts’ industry knowledge and access to company senior management as defining criteria in fund managers’ decisions. Finally, in contrast to extant literature, past forecast accuracy and analyst pedigree were rated lower in the pecking order in terms of usefulness in investment decision-making process of fund managers. Going forward, while this extensive field study identifies significant aspects of investment decision-making process of institutional investors in emerging markets, it also raises an intriguing paradox that the most researched topics like forecast accuracy are not that relevant for actual practitioners while more important criteria do not have too much research coverage. Our study provides strong outputs to sell side analysts in terms of their roles and working relationship with fund managers. Sell side analysts play a central role in shaping up the decision-making of institutional investors, and this study can go on a long way in improving service levels as well as nature of their interactions. Our study also has profound implications for various stakeholders such as companies, sell side analysts, policy makers, researchers and students of finance in terms of detailed understanding of investment processes. Such work would be useful for regulators, especially in the context of emerging markets, to get a deeper understanding of investment processes to frame better policy for transparency and compliance. Sell-side analysts can also use our work to focus on the activities and attributes useful to institutional investors so that they can improve their service levels. Notes 1. Although the primary focus of our study was Indian equities, in some cases interviewees were also responsible for managing hybrid or balanced funds having other asset classes. www.pwc. com/ng/en/press-room/global-assets-under-management-set-to-rise.html 2. In an Indian setting, fund managers are responsible for managing and performance of the designated portfolios. Buy side analysts have a primary responsibility of multiple sectors and are responsible for issuing buy/sell recommendation of company in assigned sectors. www. amfiindia.com/indian-mutual 3. Scheduling of interviews was a complex exercise on account of timing availability and workrelated travel of interviewees. However, we have been able to complete all interviews planned on time. Fund “alpha” is defined in industry as the outperformance against a declared benchmark. 4. The interview guide containing broad themes was followed in each and every interview with the respondents. NAV = net asset value of the fund. References Abarbanell, J.S. and Bernard, V.L. (1992), “Tests of analysts’ overreaction/underreaction to earnings information as an explanation for anomalous stock price behavior”, The Journal of Finance, Vol. 47 No. 3, pp. 1181-1207. Ali, A., Klein, A. and Rosenfeld, J. (1992), “Analysts’ use of information about permanent and transitory earnings components in forecasting annual EPS”, The Accounting Review, Vol. 67 No. 1, pp. 183-198. Arnold, J. and Moizer, P. (1984), “A survey of the methods used by UK investment analysts to appraise investments in ordinary shares”, Accounting and Business Research, Vol. 14 No. 55, pp. 195-207. Asquith, P., Mikhail, M.B. and Au, A.S. (2005), “Information content of equity analyst reports”, Journal of Financial Economics, Vol. 75 No. 2, pp. 245-282. Role of sell side analyst outputs QRFM Barker, R.G. (1998), “The market for information – evidence from finance directors, analysts and fund managers”, Accounting and Business Research, Vol. 29 No. 1, pp. 3-20. Belkaoui, A., Kahl, A. and Peyrard, J. (1977), “Information needs of financial analysts: an international comparison”, International Journal of Accounting Education and Research, Vol. 13, pp. 19-27. Berger, P.G., Ham, C.G. and Kaplan, Z.R. (2019), “Do analysts say anything about earnings without revising their earnings forecasts?”, The Accounting Review, Vol. 94 No. 2, pp. 29-52. Beyer, B., Guragai, B. and Rapley, E.T. (2021), “Discontinued operations and analyst forecast accuracy”, Review of Quantitative Finance and Accounting, Vol. 57 No. 2, pp. 595-627. Bradshaw, M.T. (2011). Analysts’ forecasts: what do we know after decades of work?, SSRN. Brown, L.D., Call, A.C., Clement, M.B. and Sharp, N.Y. (2016), “The activities of buy-side analysts and the determinants of their stock recommendations”, Journal of Accounting and Economics, Vol. 62 No. 1, pp. 139-156. Chang, Y.Y. and Hao, W. (2020), “Negativity bias of analyst forecasts”, Journal of Behavioral Finance, pp. 1-14. Cheng, Y., Liu, M.H. and Qian, J. (2006), “Buy-side analysts, sell-side analysts, and investment decisions of money managers”, Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis, Vol. 41 No. 1, pp. 51-83. Choi, H., Hu, R. and Karim, K. (2020), “The effect of consistency in book-tax differences on analysts’ earnings forecasts: evidence from forecast accuracy and informativeness”, Journal of Accounting and Public Policy, Vol. 39 No. 3, p. 106740. Coleman, L. (2014), “Why finance theory fails to survive contact with the real world: a fund manager perspective”, Critical Perspectives on Accounting, Vol. 25 No. 3, pp. 226-236. De Bondt, W.F.M.M. and Thaler, R.H. (1990), “Do security analysts overreact?”, The American Economic Review, Vol. 80 No. 2, p. 52. Dechow, P.M., Hutton, A.P. and Sloan, R.G. (2000), “The relation between analysts’ forecasts of longterm earnings growth and stock price performance following equity offerings”, Contemporary Accounting Research, Vol. 17 No. 1, pp. 1-32. Drachter, K., Kempf, A. and Wagner, M. (2007), “Decision processes in German mutual fund companies: evidence from a telephone survey”, International Journal of Managerial Finance, Vol. 3 No. 1, pp. 49-69. Dreman, D.N. and Berry, M.A. (2006), “Analyst forecasting errors and their implications for security analysis”, Financial Analysts Journal, Vol. 51 No. 3, pp. 30-41. Easterwood, J.C. and Nutt, S.R. (1999), “Inefficiency in analysts’ earnings forecasts: systematic misreaction or systematic optimism?”, The Journal of Finance, Vol. 54 No. 5, pp. 1777-1797. Easton, P.D. and Sommers, G.A. (2007), “Effect of analysts’ optimism on estimates of the expected rate of return implied by earnings forecasts”, Journal of Accounting Research, Vol. 45 No. 5, pp. 983-1015. Ferrer, E., Santamaría, R. and Suarez, N. (2020), “Complexity is never simple: intangible intensity and analyst accuracy”, BRQ Business Research Quarterly, doi: 10.1177/2340944420931871. Foster, F.D. and Warren, G.J. (2016), “Interviews with institutional investors: the how and why of active investing”, Journal of Behavioral Finance, Vol. 17 No. 1, pp. 60-84. Francis, J. and Philbrick, D. (2006), “Analysts’ decisions as products of a multi-task environment”, Journal of Accounting Research, Vol. 31 No. 2, p. 216. Frankel, R. and Lee, C.M.C. (1998), “Accounting valuation, market expectation, and cross-sectional stock returns”, Journal of Accounting and Economics, Vol. 25 No. 3, pp. 283-319. Glaser, B.G. (1992), Basics of Grounded Theory Analysis: Emergence vs Forcing, Sociology press. Groysberg, B., Healy, P.M., Chapman, C.J., Shanthikumar, D.M. and Gui, Y. (2007), “Do buy-side analysts out-perform the sell-side?”, available at: SSRN 806264. Guest, G., Bunce, A. and Johnson, L. (2006), “How many interviews are enough?: An experiment with data saturation and variability”, Field Methods, Vol. 18 No. 1, pp. 59-82. Henningsson, J. (2009), “Fund managers as cultured observers”, Qualitative Research in Financial Markets, Vol. 1 No. 1, pp. 27-45. Hermanson, D.R., Tompkins, J.G., Veliyath, R. and Ye, Z.S. (2012), “The compensation committee process”, Contemporary Accounting Research, Vol. 29 No. 3, pp. 666-709. Hobbs, J. and Singh, V. (2015), “A comparison of buy-side and sell-side analysts”, Review of Financial Economics, Vol. 24, pp. 42-51. Holland, J. (2006), “Fund management, intellectual capital, intangibles and private disclosure”, Managerial Finance, Vol. 32 No. 4, pp. 277-316. Holland, J.B. and Doran, P. (1998), “Financial institutions, private acquisition of corporate information, and fund management”, The European Journal of Finance, Vol. 4 No. 2, pp. 129-155. Imam, S. and Spence, C. (2016), “Context, not predictions: a field study of financial analysts”, Accounting, Auditing and Accountability Journal, Vol. 29 No. 2, pp. 226-247. Jaiyeoba, H.B. and Haron, R. (2016), “A qualitative inquiry into the investment decision behaviour of the Malaysian stock market investors”, Qualitative Research in Financial Markets, Vol. 8 No. 3, pp. 246-267. Jaiyeoba, H.B., Adewale, A.A., Haron, R. and Ismail, C.M.H.C. (2018), “Investment decision behaviour of the Malaysian retail investors and fund managers: a qualitative inquiry”, Qualitative Research in Financial Markets, Vol. 10 No. 2, pp. 134-151. Kamarudin, F., Nassir, A.M., Yahya, M.H., Said, R.M. and Nordin, B.A.A. (2014), “Islamic banking sectors in Gulf cooperative council countries: analysis on revenue, cost and profit efficiency concepts”, Journal of Economic Cooperation and Development, Vol. 35 No. 2, pp. 1-42. Kamarudin, F., Sufian, F. and Nassir, A.M. (2016), “Does country governance foster revenue efficiency of Islamic and conventional banks in GCC countries?”, EuroMed Journal of Business, Vol. 11 No. 2, pp. 181-211. Ke, B. and Yu, Y. (2006), “The effect of issuing biased earnings forecasts on analysts’ access to management and survival”, Journal of Accounting Research, Vol. 44 No. 5, pp. 965-999. Kothari, S.P., So, E. and Verdi, R. (2016), “Analysts’ forecasts and asset pricing: a survey”, Annual Review of Financial Economics, Vol. 8, pp. 197-219. Kvale, S. and Brinkmann, S. (2009), Learning the Craft of Qualitative Research Interviewing, Sage Publications, Thousand Oaks. Lai, M.M., Low, K.L.T. and Lai, M.L. (2001), “Are Malaysian investors rational?”, Journal of Psychology and Financial Markets, Vol. 2 No. 4, pp. 210-215. Lim, T. (2001), “Rationality and analysts’ forecast bias”, The Journal of Finance, Vol. 56 No. 1, pp. 369-385. McNichols, M.F. and O’Brien, P.C. (1997), “Self-Selection and analyst coverage”, Journal of Accounting Research, Vol. 35 No. 3, pp. 167-199. Malterud, K., Siersma, V.D. and Guassora, A.D. (2016), “Sample size in qualitative interview studies: guided by information power”, Qualitative Health Research, Vol. 26 No. 13, pp. 1753-1760. Marshall, C. and Rossman, G.B. (2011), “Managing, analyzing, and interpreting data”, C. Marshall and GB Rossman, Designing Qualitative Research, Vol. 5, pp. 205-227. Mendenhall, R.R. (1991), “Evidence on the possible underweighting of earnings-related information”, Journal of Accounting Research, Vol. 29 No. 1, pp. 170-179. Middleton, C.A., Fifield, S.G. and Power, D.M. (2007), “Investment in central and Eastern European equities: an investigation of the practices and viewpoints of practitioners”, Studies in Economics and Finance, Vol. 24 No. 1, pp. 13-31. Mohamad, S.G.B.M.G.B and Perry, C. (2015), “How fund managers in Malaysia make decisions”, Qualitative Research in Financial Markets, Vol. 7 No. 1, pp. 72-87. Role of sell side analyst outputs QRFM Pike, R., Meerjanssen, J. and Chadwick, L. (1993), “The appraisal of ordinary shares by investment analysts in the UK and Germany”, Accounting and Business Research, Vol. 23 No. 92, pp. 489-499. Qu, S.Q. and Dumay, J. (2011), “The qualitative research interview”, Qualitative Research in Accounting and Management, Vol. 8 No. 3, pp. 238-264. Richardson, S.A., Teoh, S.H. and Wysocki, P.D. (2004), “The walk-down to beatable analyst forecasts”, Contemporary Accounting Research, Vol. 21 No. 4, pp. 885-924. Strauss, A. and Corbin, J. (1990), Basics of Qualitative Research, Sage publications. Tuckett, D. (2012), “Financial markets are markets in stories: some possible advantages of using interviews to supplement existing economic data sources”, Journal of Economic Dynamics and Control, Vol. 36 No. 8, pp. 1077-1087. Corresponding author Arit Chaudhury can be contacted at: achaudhury@imt.edu For instructions on how to order reprints of this article, please visit our website: www.emeraldgrouppublishing.com/licensing/reprints.htm Or contact us for further details: permissions@emeraldinsight.com