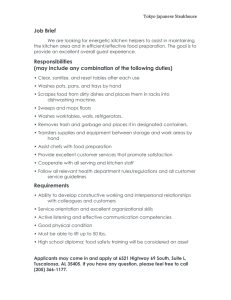

International Journal of Urban Sustainable Development ISSN: 1946-3138 (Print) 1946-3146 (Online) Journal homepage: https://www.tandfonline.com/loi/tjue20 Assessing the role and effectiveness of kitchen gardening toward food security in Punjab, Pakistan: a case of district Bahawalpur Muhammad Mohsin, Muhammad Mushahid Anwar, Farrukh Jamal, Fahad Ajmal & Juergen Breuste To cite this article: Muhammad Mohsin, Muhammad Mushahid Anwar, Farrukh Jamal, Fahad Ajmal & Juergen Breuste (2017) Assessing the role and effectiveness of kitchen gardening toward food security in Punjab, Pakistan: a case of district Bahawalpur, International Journal of Urban Sustainable Development, 9:1, 64-78, DOI: 10.1080/19463138.2017.1286349 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/19463138.2017.1286349 © 2017 The Author(s). Published by Informa UK Limited, trading as Taylor & Francis Group. Published online: 22 Feb 2017. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 11607 View related articles View Crossmark data Citing articles: 3 View citing articles Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at https://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=tjue20 International Journal of Urban Sustainable Development, 2017 Vol. 9, No. 1, 64–78, http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/19463138.2017.1286349 Assessing the role and effectiveness of kitchen gardening toward food security in Punjab, Pakistan: a case of district Bahawalpur Muhammad Mohsina*, Muhammad Mushahid Anwarb*, Farrukh Jamalc, Fahad Ajmald and Juergen Breustee a Department of Geography, Govt. S.E. College, Bahawalpur, Punjab, Pakistan; bDepartment of Geography, University of Gujrat, Gujrat, Punjab, Pakistan; cDepartment of Statistics, Govt. S.A. Postgraduate College, Dera Nawab Sahib, Bahawalpur, Punjab, Pakistan; dDepartment of Botany, University of the Punjab, Lahore, Punjab, Pakistan; e Department of Geography and Geology, University Salzburg, Salzburg, Austria (Received 11 January 2016; accepted 19 January 2017) Food security is one of the leading issues of many governments globally. Kitchen gardening is the innovative project initiated by the Government of Punjab (Pakistan) to provide instant aid to dwellers by self-produced fresh vegetables. The present investigation was conducted in the district Bahawalpur. The objectives were to explore the main benefits of kitchen gardening, to identify the places used for this activity, to identify the growers’ perceptions and to give suggestions to improve the project. Two urban and one rural tehsils of district Bahawalpur were selected as study areas. Secondary data were collected from several sources while primary data gathered through a mobile phone survey and analyzed by applying descriptive and inferential statistics using SPSS software. The findings have justified that dominant share of growers have sown the seed kits for vegetables production, mostly for home consumption and was satisfied with the quality and price of seed kit. Most of the growers certified the efficiency of the project in the regular provision of fresh and healthy vegetables. Hence, the project is a successful endeavor and still continuing in the province, benefiting the masses and encouraging urban agriculture. The outcome of the investigation is suggestions to further improve this project. Keywords: Food security; kitchen gardening; urban agriculture; district Bahawalpur; Punjab province Introduction Increasing urbanization and food security are among the key issues of the present era (FAO 2011). In recent decades, the safe and regular access of food to many rural and poor urban households has become uncertain, creating concerns of food security in many developing countries. Millions of the people around the globe are unable to purchase or have the access to sufficient food for themselves and their families (Nkosi et al. 2014). Therefore, safe food production and secure food supply are critical issues for low-income countries and it is important to develop all possible methods for the production and distribution of food (Arshad Shafqat 2012; Cameron & Wright 2014). In Germany, innovative forms of urban agriculture, such as Zero-Acreage Farming (ZFarming) are being practiced. ZFarming involving rooftop gardens, indoor farms and other building-related forms have contributed significantly to food supply in *Corresponding author. Email: chairperson.geosciences@uog.edu.pk © 2017 The Author(s). Published by Informa UK Limited, trading as Taylor & Francis Group. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives License (http:// creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/), which permits non-commercial re-use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited, and is not altered, transformed, or built upon in any way. International Journal of Urban Sustainable Development addition to providing numerous environmental, economic and social benefits (Specht et al. 2014). Major food items such as vegetables and fruits are considered vital for the rapidly increasing populations of developing countries like Pakistan, India and Bangladesh. Therefore, kitchen gardens (or home-based gardens) can play a pivotal role to alleviating problems of hunger and malnutrition in these countries. Kitchen gardens have already proven to be an important subsidiary source of food in India and Sri Lanka (Halder & Pati 2011; Galhena et al. 2013). Literally, ‘Kitchen gardens’ refer to food grown in or around the house for household use (Evans & Jespersen 2001). Home gardens may be kitchen garden, a mixed garden, or backyard, farmyard and compound garden or homestead garden. Kitchen or home gardening is an earliest and most extensive food production system found throughout the world (Landauer & Brazil 1985; Rowe 2009). In many parts of the world, the practice of a community gardening is widespread as both collective gardens and individually allocated spaces (Holland 2004). The practice of collective community gardens is useful and frequently adopted in many developed countries (e.g. Australia) as a useful activity but less applicable in countries like Pakistan where land ownership patterns and utilization highly differ from these countries in terms of individual preferences and existing land uses. In Pakistan, people grow vegetables individually or on household basis in spaces within their possession rather in a collective effort on allotted space. Hence, encouraging or enhancing vegetable gardening at home can play a significant role in improving food security to resource poor rural and urban households in developing countries like Pakistan and providing additional sources of fresh and nutritionally rich food products (Asaduzzaman et al. 2011; Galhena 2012). The various social benefits that have emerged from kitchen gardening practices are health and nutrition, enhanced income, self-employment, food security within the household and community social life (Rehman et al. 2013). Fruits and vegetable production gives households direct access to 65 important nutrition that might not be within their budget to purchase (Talukder et al. 2001; Heim et al. 2009). Kitchen gardening has also proved cost-effective and sustainable method for producing organic vegetables such as cauliflower, radish and turnip (Titilola et al. 2012; Rani et al. 2013). In Mexico, the house garden is considered a specified site for the reproduction of cultural relations and plays a key role in family life (Christie 2004). In Benin, vegetable farming has provided a balanced diet to urban populations and enhanced farmers’ household income and living standard (Allagbé et al. 2014). In low-income housing areas of urban Penang (Malaysia), kitchen gardens have proved a symbol of place, identity and sense of belonging for local low-cost flat residents (Ghazali 2013). With its burgeoning population, food security has now become the major objective of the Government of Pakistan and policymakers have focused on formulating a sound food policy leading to food security (Tariq et al. 2014). Nevertheless, in recent years Pakistan has witnessed increased poverty levels and higher risk of food insecurity in many areas. For instance, about 12% of the Potohar district population lacks food security and another 38% are at high risk of it (Abbasi et al. 2014). Because it is a fact that kitchen kitchen gardens have great potential for improving household food security and alleviating micronutrient deficiencies (FAO 2010), the main objectives of this study is to explore the benefits of the kitchen gardening project, to identify place, area and yield output of kitchen gardens, and to investigate the grower’s perceptions and suggestions for further improvement to the project. Hence, this study sought to summarize specific benefits of kitchen gardening reported in the existing literature on urban agriculture in the context of Punjab province in general and district Bahawalpur in particular. Kitchen gardening project in Punjab: background and progress The kitchen gardening project was initiated by the Government of Punjab in the year of 2010–2011 66 Table 1. M.M. Anwar et al. Brief description of kitchen gardening project in Punjab, Pakistan. Name of the project Location Sponsoring agency Project period Project objectives Upscaling of kitchen gardening in Punjab All district of Punjab Government of Punjab 36 months (2011–2012 to 2013–2014) but still continue ✓ To create awareness among masses about production of vegetables for their own consumption. ✓ To disseminate vegetable production technology for kitchen gardening. ✓ To advertisement the kitchen gardening benefits to increase the interest of growers. ✓ Creating demand of seed kits through NGOs and public sector organizations. ✓ To provide seed kits to the kitchen gardeners having the seeds of seasonal vegetables to encourage the kitchen gardening. Source: Govt. of Punjab (2011b). with the goal of promoting and protecting peoples’ health and reducing their food expenditures (Table 1). Initially, the estimated period of the project was for 3 years with the allocation of 38.74 million rupees (PKR) (about 410,000 US $) for the project. The funds invested largely on operational works such as the procurement and selling of seed kits and publication and distribution of introductory pamphlets. During the target period (2011–2014), about 400,000 seed kits were distributed among the people successfully (Govt. of Punjab 2011b). Additional investments were also made to train people by creating production technology compacts disk (CDs) and pamphlets (Tables 2 and 3). The prepared seed kits contained eight different seeds of popular vegetables such as ladyfinger, bitter gourd, bottle gourd, cucumber, long melon for planting in summer season and radish, carrot, turnip, fenugreek, coriander, cauliflower for winter season vegetables. The single seed kit has a weight of 150 g with the set price of 50 rupees (PKR) (about 48 US $ cent) per seed kit to make it affordable for people (Govt. of Punjab 2010). It is also been planned to utilize the open spaces in educational and institutional lands with the assistance of the respective institutes. The project is a joint venture of public and private sector and operational in a systematic coherent order from top (provincial government) to bottom (a single grower). In this connection, the provincial agriculture (extension) department was assigned main duties as first to promote kitchen gardening and publicize the trend with arranging seminars, demonstrations, workshops, trainings, walks, public campaign, etc. along with identifying suitable areas to disseminate the knowledge, awareness and ways of successful kitchen gardening. The awareness workshops and seminars were held at schools, colleges and public places by the concerned officials and this activity turned out to be very fruitful after the exciting participation of public to know and learn the ways of effective vegetable growing from household to community level. Apart from that, the participants were given brief training and supplementary material to get more understanding of the kitchen gardening. For instance, they were instructed by agricultural experts to learn effective ways of plowing and preparing land, watering, fertilizing, etc. and provided literature pamphlets, CDs and helpline contacts. Other than that, the department was also asked to arrange road shows and an effective media campaign of the project (Daily Dawn 2011). Initially, in 2011, Government of Punjab had prepared about 80,000 seed packets of various vegetables on automatic machines (Islam 2011). While in 2013, the prepared seed kits selling target was set of 70,000 kits (Table 4) among the 36 districts of Punjab in summer and winter season vegetables. International Journal of Urban Sustainable Development Table 2. 67 Cost of kitchen gardening project (figures in Rs. million). Item Establishment charges Operational/contingencies Machinery and equipment Total 2011–2012 2012–2013 2013–2014 Total 0.3 9.57 0.13 10 0.5 13.97 0 14.47 0.3 13.97 0 14.47 1.3 37.51 0.13 38.94 Source: Govt. of Punjab (2011b). Table 3. Year-wise activities of kitchen gardening project in Punjab (figures in nos.). Activity Procurement and selling of seed kits (5 Marla) Selling of seed kits (5 Marla) Training of facilitators Provision of free seed kits for demonstration plants Production and distribution of pamphlets Trainings in schools, govt. offices, vocational training centers and residential areas Persons to be trained Preparation of CDs of production technology Selling of CDs of production technology 2011– 2012 2012– 2013 2013– 2014 Total 100,000 100,000 72 216 150,000 900 150,000 150,000 72 216 200,000 900 100,000 100,000 72 216 200,000 900 400,000 400,000 216 648 550,000 2,700 27,000 5,000 5,000 27,000 5,000 5,000 27,000 5,000 5,000 81,000 15,000 15,000 Source: Govt. of Punjab (2011b). Results The set targets for the sale of seed kits were achieved throughout the province within the timeframe and had marked the awareness and fame of the project among urban and semi-urban population. Regardless of the apparent significant and hopeful outcomes, there has been criticism that the seed packets have not reached to the deserved poor growers living in urban areas of the province and thus this whole exercise may not yield desired outcomes (Hasan 2011). Nevertheless, the project has achieved up to mark success and popularity toward creating a safe environment, healthy food and engagement of the public in this useful activity across the province (Table 4). For instance, in 2012, the sale of kitchen gardening seed kits increased from 5,000 to 170,000 in rabi (winter) season and 3,000 to 75,000 in kharif (summer) season (Govt. of Punjab 2012). Later in 2013, Planning & Development Department of the Government of Punjab conducted an extensive survey. The survey evaluation results indicated that the project achieved substantial success in the provision of economical and secure vegetables to the masses with better yield in summer and winter seasons. In order to monitor the project efficiency and acceptance of people, the district Agriculture (Extension) Department of Bahawalpur was also directed by the provincial government to maintain and submit of a kitchen gardening project report regarding received and distributed/sold seed kits and their deposited money on daily basis. Sales centers were established in selected tehsils’ (administrative subdistricts) offices of agriculture (extension) department and other government offices to sell the seed kits to residents (Table 5). In this way, the considerable 68 Table 4. M.M. Anwar et al. Distributed selling target of kitchen gardening seed kits in 2013 in Punjab. Target (figures in nos.) Sr. no. 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 Name of district Kharif season (summer vegetables) Rabi season (winter vegetables) 600 1,000 1,200 1,000 1,000 1,000 800 1,000 2,500 1,000 800 1,000 1,200 1,000 1,500 1,100 1,000 1,000 3,000 1,500 1,400 600 1,400 1,000 1,000 1,000 1,000 1,000 1,000 500 1,000 1,000 1,000 1,200 1,200 500 40,000 70,000 500 500 1,500 500 1,500 1,000 500 500 2,500 500 500 500 1,500 1,000 1,500 500 500 500 2,500 1,000 500 500 2,000 500 500 500 500 500 1,500 500 500 500 500 500 500 500 30,000 Attack Chakwal Rawalpindi Jhelum Sargodha Khushab Mianwali Bhakkar Lahore Kasur Nankana Sahib Sheikupura Gujranwala Hafizabad Sialkot Narowal Gujrat M.B.Din Faisalabad T.T.Singh Jhang Chiniot Multan Lodhran Khanewal Vehari Sahiwal Pakpattan Okara D.G.Khan Layyah Muzaffargarh Rajanpur Bahawalpur Bahawalnagar Rahim Yar Khan Total Grand total Source: Govt. of Punjab (2013). amount of project operational costs (e.g. preparing of seed kits, publishing and creation of pamphlets and CDs) were recovered. Although, the sale of seeds did not pay for the cost of the project, it did meet the cost-recovery target. After selling the seed kits, the selling data were sent to the district agriculture (extension) department along with the details of total recovered amount (money) that was later deposited in government treasury account. International Journal of Urban Sustainable Development Table 5. Sr. no. 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 69 Kitchen gardening seed kits progress in Bahawalpur in 2011, 2012 and 2013. Name of tehsil/center Bahawalpur (City and Saddar) Ahmedpur East Yazman Khairpur Tamewali Hasilpur Divisional Forest Officer/ Bahawalpur/Lal Sohanra AO Nursery Bahawalpur Total Grand total Dated 20 October 2011 Dated 01 November 2012 Dated 25 October 2013 No. of seed kits sale centers Seed kits received and distributed Seed kits received and distributed Seed kits received and distributed 4 1,250 900 850 4 2 1 2 1 650 950 500 355 100 500 500 200 300 100 700 550 450 500 25 1 45 15 15 3,850 9,550 – 2,500 (Al-Sadiq Desert Organization) 300 3,200 Source: District Agriculture (Extension) Department of Bahawalpur (2014). Materials and methods Study area Bahawalpur district has a rich economic, historic, demographic and physiographic place in Punjab province. The district was once the part of the Bahawalpur state ruled by local Nawab (royal noblemen) before its annexation with Pakistan in 1955. It is positioned between 27°40′ and 29°50′ North latitudes and between 70°54′ and 72°50′ East longitudes and occupied an area of 24,830 sq. km (Govt. of Pakistan 1998) (Figure 1). More than two-third area of the district is occupied by mighty Cholistan Desert in the south, southeast and southwest. Administratively, the district is divided into six tehsils or subdivision namely Bahawalpur City, Bahawalpur Saddar, Ahmedpur East, Yazman, Khairpur Tamewali and Hasilpur. Among the 107 Union Councils (UCs or small revenue estates) exist in the district 29 are urban and 78 are rural. Rural Union Councils are mainly located around the big cities or towns and inhabited rural population predominantly is engaged in subsistence farming. The population of the district is rapidly being increased as per the national census of Pakistan (Govt. of Pakistan 1998), the population of the district consisted of 2,433,000 individuals that was increased and estimated 3,277,000 in 2011 (Table 6). Likewise, Bahawalpur is one of the 36 districts of the Punjab province where the kitchen gardening project is initiated with keeping special focus to its rapidly growing population, high poverty levels and boosting demand of cheaper, fresh food items among urban and suburban residents. Data collection Although, variety of methods and approaches found in literature that are often used in social sciences for data collection process, but many researchers have also introduced innovative methods of data gathering based on their personal knowledge and experiences, and also provide creativity in mutual coherence between researchers and respondents like management of the workshop bus trip, etc. (Cameron et al. 70 M.M. Anwar et al. Figure 1. Location map of district Bahawalpur showing study areas. Source: Authors (2015). Table 6. Number of Union Councils (UCs) and their population in Bahawalpur district. Population (thousand persons) No. of Union Councils As per 1998 census Est. on 31 December 2011 Total Urban Rural Total Urban Rural Total Urban Rural 1998 urban pop. (%) 107 29 78 2,433 665 1,768 3,277 896 2,381 27.3 Source: Govt. of Punjab (2011a). 2010). Similarly, the current research has also utilized cellular mobile phone (the most widely used communication medium in Pakistan as estimated 128.04 million users in early 2016 (PTA 2016) survey and field investigations as primary data collection methods employing a semi-structured interview with both open and close-ended questions. Wherein, majority of the questions were closed-ended (e.g. purpose of vegetable sowing, cost of seed kit, effectiveness of the project, main expenditures of the International Journal of Urban Sustainable Development 71 project, main benefits of the project, etc.) whereas few questions (e.g. growers opinions about the betterment of the project) were open ended. The opinions of the growers were categorized in order to analyze them statistically. The average length of the conversation with interviewee varied between 10–15 min. During this phase, some difficulties have also been tapped due to unawareness and hesitant communication of the interviewees probably resulted from the new method of data acquisition. However, later on they fully cooperated, happily shared and expressed about their kitchen gardening experiences when they were briefed about the purpose and meaning of the study. Samples and sampling procedure Total 100 growers (35 each from Bahawalpur City and Bahawalpur Saddar, respectively, and 30 from Ahmedpur East tehsil (subdistrict) were selected as target samples. The sample size taken one-third of the total numbers given in the lists was determined using simple percentage formula based on the growers numbers mentioned in the lists (tehsil wise) in the following procedure; Number of Growers in One List/Total Growers in All Lists × 100 (List 1: Bahawalpur City) 101/289 × 100 = 34.95 (List 2: Bahawalpur Saddar) 101/289 × 100 = 34.95 (List 3: Ahmedpur East) 87/289 × 100 = 30.10 The random stratified sampling was used to select respondents from three tehsils of Bahawalpur viz. Bahawalpur City, Bahawalpur Saddar and Ahmedpur East mostly from the residents resided in urban and semi-urban areas, and they were contacted by the authors separately for getting necessary information. In addition to that, field visits were also made to verify the respondents’ responses and ground-truthing (Figure 1 and Figure 2) The whole exercise took the period of more than 1 month. The cellular mobile numbers Figure 2. Vegetables seeds sown in kitchen garden. Source: Field survey (2014). Figure 3. A demonstration plot of kitchen gardening. Source: Field survey (2014). of these persons were chosen and obtained from the detailed lists of growers contacts who purchased the seed kits arranged by Agriculture (Extension) Department of district Bahawalpur. These lists were prepared tehsil wise and mentioned other minor details as well (e.g. grower’s address, plot size). Data Analysis: Initially, the collected data were in raw format and were properly arranged, 72 M.M. Anwar et al. tabulated and then subjected to statistical operations using Statistical Package for Social Sciences 16.0 software. By applying descriptive (frequencies and percentages) and inferential (Chi-square test) statistics, the attempt was made to determine the significance and effectiveness of kitchen gardening project among the masses. Finally, study area map was generated in Arc View 3.2a software. Results and discussion Expenditures, efficiency and main benefits of kitchen gardening Cost-effectiveness (affordability) and its related issues are considered essential in any community development project. Table 7 shows the project benefits regarding cost affordability, quality and expenditures. Out of 100 respondents who have purchased seed kits from sales centers, 84% respondents have sown their seed kits for vegetables growing. About 16% respondents had not planted their seeds due to various reasons such Table 7. as lack of time, family affairs, less space, unawareness, etc. A previous study conducted in national capital Islamabad through personal interview using questionnaire found that kitchen gardening activity was practiced by 90% surveyed people at their homes who used their production for home consumption and numerous other benefits (Rehman et al. 2013). Similarly, in study areas, 82% growers have grown the vegetables for their own daily household consumption. Shaheb et al. (2014) also reported that production of vegetables and fruits at homes provides the household with direct access to important nutrients. The majority of the growers were urban residents resided in Bahawalpur City and Ahmedpur East City while, about 18% had grown the vegetables for selling in local markets. These were mainly the residents of semi-urban and rural localities and grew vegetables in comparatively large-size land plots. The advantages of kitchen gardening, particularly in the context of low-income households of developing countries, are manifold and support the growers in many ways. Drescher et al. (2000) Expenditures, efficiency and main benefits of kitchen gardening project. Attributes Have you sown seed kit? Purpose of vegetable growing Quality of seeds Chi-square = 62.19 Is the cost of seed kit affordable? Chi-square = 80.04 Estimated expenditures on vegetable growing Efficiency of project Chi-square = 50.65 Main benefits Response of respondents (frequency and percentage) Yes 84 (84%) Home consumption 69 (82.1%) Excellent 11 (13.1%) d.f. = 1 Yes 83 (98.8%) d.f. = 1 level 100–200 PKR No 16 (16%) Selling purpose 15 (17.9%) Good 52 (61.9%) Sig. = .000** No 1 (1.2%) Sig. = .000** 200–300 PKR 27 (32.1%) Yes 74 (88.1%) d.f. = 1 Improved quality and economical 21 (25%) 35 (41.7%) No 10 (11.9%) Sig. = .000** Safe and healthy 30 (35.7%) **significant at 5% level. Source: Telephonic Survey (2014). Average 14 (16.7%) Poor 7 (8.3%) 300–400 PKR 400–500 PKR 2 (2.4%) 20 (23.8%) Nutritious and tasty 25 (29.7%) Idle 8 (9.5%) International Journal of Urban Sustainable Development stated that many social benefits have emerged from kitchen gardening practices including better health and nutrition, increased income, employment opportunities and food security of household and community social life. A recent study conducted in district Muzaffargarh (Punjab, Pakistan) concluded that the women are particularly more aware about kitchen gardening. Hence, the study based on training activity is designed to involve, educate women about different ways of exercising effective kitchen gardening. They were engaged in growing of vegetables in due time with proper management and be able to save time and money in terms of buying vegetables from the market (Cheema 2011; Bajwa et al. 2015). Similarly, in study areas the women have also actively participated in the activity along with their men and children. The results showed that the seed kits used for kitchen gardening usually contained different seeds of vegetables and were well packed keeping the standards and design in view. About 13% growers reported that the quality of seeds was excellent, about 62% asserted that quality of seeds was good and 16.7% responded that quality of seeds was average. The Chi-square value (62.19) also verifies the high quality of seeds with highly significant (p-value .000) association. These results proved that the quality of vegetable seeds was overall good and productive in quality. About 8.3% growers were not satisfied with seed kit quality and they considered it poor. When they were asked about this poor quality of the seeds, majority of them complained that after sowing seeds they have not acquired any output. When an expert of the district agricultural office was inquired about this under achieved output, he argued that the seed kit contained certified seed variety and the output failure might be the result of improper watering, infertile soil or less knowledge of vegetable sowing. The affordability of the cost is also an important component regarding the predicted success of the project and hence it was kept low as 50 PKR (about 48 US $ cent) per kit. Previous study conducted in Bangladesh also highlighted the shortage of irrigation water, quality seeds and inputs cost as major problems faced by 73 growers in kitchen gardening (Rahman et al. 2008). Study results show that about 99% growers were happy with the seed kit price and have no problem to purchase this. Usually, the vegetables produced in kitchen gardening do save money and improved taste than vegetables and fruit bought from grocery store (Christensen 2011). While only a single grower was unhappy with the stipulated price. The Chi-square value (80.04) also certifies strong association with p-value (.000) between the price of seed kit and growers purchasing behavior. The estimated expenditures made by growers in vegetables growing were also varying and range from low to medium in cost. About 32.1% growers expenditures on vegetable growing were between 100–200 PKR, a majority of 41.7% growers spent 200–300 PKR, 23.8% were spent 300–400 PKR on the growing of vegetables while 2.4% have made the highest expenditures ranging from 400–500 PKR. These expenditures were made in account of watering and plowing of plots when asked. These results certify that the growers have not spent much on the growing of vegetables. When they were asked about project effectiveness and main benefits, then about 88% growers argued that the project is a useful initiative in alleviating their daily-based kitchen expenditures and a source of an uninterrupted supply of fresh and safe nutritious vegetables on a reasonable cost. In addition, they had obtained variety of benefits from this project as 25% growers responded that they got improved quality (in terms of seed germination and growth of plant) and economical vegetables, 35.7% considered this project as a source of providing safe and healthy vegetables, 29.7% trusted the taste and nutritious features of the produced vegetables. Being a healthy activity, kitchen gardening decreases people’s fiscal expenditures and bring self-sufficiency in vegetables production. Additionally, they get healthy and nutritious food from their kitchen gardens (Rehman et al. 2013). It is also evident from a study that kitchen gardening has proved a reasonable livelihood approach for resource poor people in terms of nutrient supply, calorie intake and economic benefits (Chayal et al. 2013). A 74 M.M. Anwar et al. study conducted in Kenya also reported that about 48% of the respondents do not purchase vegetables after establishing kitchen gardens and about 99% of the respondents think that the kitchen gardens have improved their nutritional variety (Njuguna 2013). In contrary, only 9.5% growers were not satisfied with the outcomes and they blamed it a redundant or useless effort. Despite this, the Chi-square value (50.65) also supports growers’ perceptions about project effectiveness with high significance p-value (.000). These results again testify that overwhelming growers (90.5%) were fully benefited and satisfied with vegetables yield output and thus favored the project with its obvious effectiveness and numerous advantages. Thus, it is proved a purposeful and productive venture and should be promoted as it would help people in dropping kitchen expenditures, pollution and creating healthy environments at homes and vicinity (Khan 2013). Specified place, area, inputs and yield output of kitchen gardening For a successful kitchen gardening, it is important that how much area required for vegetable cultivation along with seed, fertilizer and Table 8. organic pesticides availability? (AARI, 2015). The efforts made by district government to conduct awareness seminars and training sessions about kitchen gardening have brought notable positive changes in people’s behavior about the project and they have gained sufficient knowledge and practical training of vegetable sowing and their proper management. Table 8 portrays the specified sowing place, area and application of fertilizers for the better production of vegetables. A large number of growers (77.4%) utilized house’s lawn for the purpose of growing vegetables, 17.9% used house roofs for the growing of vegetable due to the absence of lawn or availability of less vacant space at home. The rest of the growers used earthen pots (2.4%) and plastic bottles (2.4%) for vegetable production. Although specified area in kitchen gardening is an important element having a significant impact on overall yield output (Asaduzzaman et al. 2011) yet, the majority of the growers resided in urban and semi-urban areas were having less space for vegetable growing. Further, it is also known that the growers education level, income, knowledge of vegetable sowing, training or received training literature also do matter in Place, area and use of fertilizer in kitchen gardening. Attributes Place of seed kit Sowing Specified area of vegetable sowing Major input by cost Chi-square = 116.95 Use of fertilizer for better yield Chi-square = 65.19 Type of fertilizer Major output after fertilizer use Chi-square = 126.67 Source: Telephonic Survey (2014). **significant at 5%. Response of respondents (frequency and percentage) Lawn 65 (77.4%) <1 Marla 33 (39.3%) Fertilizer 61 (72.6%) d.f. = 3 Yes 79 (94%) d.f. = 1 Urea 10 (12.3%) Increase in yield 72 (85.7%) d.f. = 2 House roof 15 (17.9%) 2–3 Marla 31 (36.9%) Labor charges 15 (17.9%) Sig. = .000**level No 5 (6%) Sig. = .000** Potash 19 (23.5%) Decrease in yield 3 (3.6%) Sig. = .000** Earthen pots 2 (2.4%) 4–5 Marla 17 (20.2%) Irrigation 5 (6%) Others 2 (2.4%) > 5 Marla 3 (3.57%) Seed kit 1 (1.2%) DAP 39 (48.1%) Change in quality 6 (7.1%) Natural manure 13 (16%) No output 3 (3.6%) International Journal of Urban Sustainable Development the site and space selection for kitchen gardening. About 39.3% growers used less than 1 Marla (local unit of land equal to 272 sq. feet) space for vegetable growing, 36.9% used 2–3 Marla (544–816 sq. feet) space for this activity. Both of these classes of growers resided in congested parts of the Bahawalpur and Ahmedpur East cities. While 20.2% and 3.57% growers in adjacent rural localities used 4–5 Marla (1,088–1,360 sq. feet) and more than 5 Marla (>1,360 sq. feet) piece of land, respectively, for kitchen gardening. Amongst majority of growers has exercised this for income generation, as it has been witnessed as a source of additional income in various previous studies (Galhena 2012; Qaiser et al. 2013; Rehman et al. 2013; Bajwa et al. 2015). Moreover, growers also have applied different kinds of inputs for better yield of vegetables; as 73.9% used fertilizers for better output and Chi-square result also considered it highly significant with p-value (.000) for better yield of vegetables, 17.8% have spent much on labor charges and mostly were the urban dwellers in Bahawalpur City. Growers also made minor expenditures in the account of irrigating vegetables (7.1%) and purchasing of seed kit (1.2%). It was recognized that target growers have used different fertilizers for better yield. Chi-square value (65.19) also denoted a considerable association regarding growers’ preferences for the use of fertilizers and expected better yield output with a highly significant p-value (.000). DAP fertilizer was famous and effective for enhancing the yield output, so the majority of the growers (50%) used this for better production, 22.6% were used Potash for increasing yield, 15.5% used natural manure (animal dung) for this purpose mostly the residents of rural areas and 11.9% growers applied Urea fertilizer for maximizing the vegetable output. These results clarify that almost all growers were willing to gain the maximum yield by applying different fertilizers to meet their daily needs of vegetables. Thus, after using fertilizers, 85.7% growers acquired an 75 increased yield of vegetables. Chi-square result (126.67) also verifies it highly significant with p-value (.000), while the rest of the growers faced a decrease in yield (3.6%), change in quality (7.1%) and no output (3.6%). These all discrepancies in yield might be the result of certain factors like lack of care, deficit water for vegetables, no application of fertilizer, less experience in vegetable sowing, etc. However, overall findings demonstrated that growers yielded maximum output of vegetables after proper care, use of fertilizer and irrigating with fresh water. Conclusion Kitchen gardening is the innovative project, initiated by the Government of Punjab with the basic objective to provide relief for the masses on daily vegetable needs and creating a safe and sustainable environment with healthy people. The findings of this study highly aid to the relative importance and hopes of kitchen gardening project in the district and clearly indicates that the set targets of kitchen gardening project in the Punjab province have almost been accomplished with considerable success. As a result, daily kitchen expenditures are greatly reduced and this activity has evolved urban agriculture too. The provincial government has invested a huge sum on the development and promotion of the project. In this regard, serious and systematic efforts have been made with the collaboration of district governments in the right direction to achieve the ultimate objectives of the project. The year-wise performance also proved the remarkable advancement of the project and all set targets are entrusted within due period. In district Bahawalpur, the same results are obtained after its inception in 2011. The allocated quota of vegetable seed kits were received and sold out timely with deep affiliation of the people noticed with this activity. Survey results also justified the project outcomes. The majority of the kitchen gardeners has grown vegetables for home consumption and was satisfied with the quality of seeds and affordability of seed kit price. Lawns and house roofs were the common places of seed sowing and mostly urban 76 M.M. Anwar et al. growers utilized less area compared with rural areas where comparatively large area of land has utilized for growing vegetables. Growers are made to vary expenditures on vegetables growing particularly on the application of fertilizers for better yield and achieved it successfully. Leading number of the growers demonstrated the efficiency of the kitchen gardening project and counted it substantial in the provision of vegetables characterized by various benefits; improved quality, economical, nutritious, tasty, etc. The same results have been justified by Chi-square analysis. Hence, it is concluded, that kitchen gardening project has achieved the target success and familiarity to provide cheap vegetables grown at household level with several advantages including healthy activity, protecting environment and lessening daily kitchen expenditures. Hence, it is still in operation in the province and benefiting the masses with numerous advantages and ensuring food security. The study is a purposeful endeavor, successfully accomplished with the combined source like mobile phone survey, in-depth interviews, regular field visits, ground truthing and participation of many stakeholders (growers, project implementers, agricultural experts, focal persons, etc.). However, the collected data by survey were limited to some extent and may not address all the aspects of growers’ kitchen gardening experiences. So, a more comprehensive future study may be required to uncover the additional potentials and benefits of the kitchen gardening. Suggestions Keeping in view the obvious outcomes and benefits of the project, and to bring further improvement in it, the following suggestions are proposed: ● The project awareness campaign should be widened to convey its benefits extensively. ● Quality of seed should be further improved. ● The household members particularly women and children should be encouraged for vegetable production. ● Government should provide more incentives ● ● ● ● ● ● (training, free seed kits, pamphlets) particularly to poor dwellers residing in semi-urban and rural localities. Private partnership on small scale should be promoted. Technical support should be provided to the growers. Electronic media (TV, radio and cable) should be utilized for project publicity. Demonstration plots of kitchen gardening should be maximized to attract the community. To increase the seed kits sale, the fixed price of seed kit should be reduced. The sale centers should be maximized for the easier access of the community. Acknowledgements The authors are deeply grateful to the Executive District Officer (EDO) Agriculture, District Officer Agriculture (Extension) Bahawalpur and their office clerical staff for the provision of essential secondary data, support and cooperative behavior. Disclosure statement No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors. Notes on contributors Muhammad Mushahid Anwar, PhD Geography, He is working as professor and chair of Department of Geography at University of Gujrat, Punjab, Pakistan. His area of interest is urban landscape ecology, urban planning. Muhammad Mohsin, M.Phil Geography, He is working as lecturer of Geography at Department of Geography, Govt. S.E. College, Bahawalpur, Punjab, Pakistan. His area of interest is Urban Planning, Urban Morphology and Structure, Urban Problems, Urban Ecology, Ruralurban Fringe Dynamics. Farukh Jamal is PhD scholar of statistics at Department of Statistics, The Islamia University Bahawalpur, Punjab, Pakistan. His area of interest is Applied Statistics, International Journal of Urban Sustainable Development Probability, Statistical Inference, Econometrics. He is working as lecturer, Govt. S.A. Postgraduate College, Dera Nawab Sahib, Bahawalpur. Fahad Ajmal is a PhD scholar at Department of Botany, University of The Punjab Lahore, Pakistan. His area of interest is Molecular Biology, Plant Physiology, Agronomy and Stress Physiology. He is working as subject specialist of Botany at Lahore, Pakistan Juergan Breuste is PhD Geography. He is working as professor and chair of Urban Landscape Ecology at Department of Geology and Geography at Salzburg University, Austria. References Abbasi SS, Marwat NK, Naheed S, Siddiqui S. 2014. Food security issues and challenges: a case study of potohar. Eur Acad Res. 2:3090–3113. Allagbé H, Aitchedji M, Yadouleton A. 2014. Genesis and development of urban vegetable farming in Republic of Benin. Int J Innovation Appl Stud. 7:123–133. Arshad S, Shafqat A. 2012. Food security indicators, distribution and techniques for agriculture sustainability in Pakistan. Int J Appl Sci Technol. 2:137–147. Asaduzzaman M, Naseem A, Singla R. 2011. Benefitcost assessment of different homestead vegetable gardening on improving household food and nutrition security in rural Bangladesh. Paper presented at Agricultural & Applied Economics Association’s 2011 (AAEA) & NAREA Joint Annual Meeting; 2011 Jul 24–26; Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, USA. Ayub Agricultural Research Institute (AARI). 2015. Kitchen gardening. [cited 2015 Sep 21]. Available from: http://www.aari.punjab.gov.pk/farmer-ser vices/for-farmers/kitchen-gardening Bajwa BE, Aslam MN, Malik AH. 2015. Food security and socio-economic conditions of women involved in kitchen gardening in Muzaffargarh, Punjab, Pakistan. J Environ Agric Sci. 4:1–5. Cameron J, Manhood C, Pomfrett J. 2010. Growing the Community of Community Gardens: research contributions. Paper presented in: Community Garden Conference: Promoting Sustainability, Health and Inclusion in the City; 2010 Oct 7–8; University of Canberra, Canberra, Australia. Cameron J, Wright S. 2014. Researching diverse food initiatives: from backyard and community gardens to international markets. Local Environ. 19:1–9. Chayal K, Dhaka BL, Poonia MK, Bairwa RK. 2013. Improving nutritional security through kitchen gardening in rural areas. Asian J Home Sci. 8:607–609. 77 Cheema KJ. 2011. Call to promote kitchen gardening. The News. Christensen TE. 2011. What is a kitchen Garden?Wise Geek. p. 1–2. Christie ME. 2004. Kitchenspace, fiestas, and cultural reproduction in mexican house-lot gardens. Geogr Rev. 94:368–390. Daily Dawn. 2011. Punjab Govt to flourish kitchen gardening. Daily Dawn. [cited 2013 Dec 29]. Available from: http://www.dawn.com/news/ 629838/punjab-govt-to-flourish-kitchen-gardening. District Agriculture (Ext.) Department of Bahawalpur. 2014. Kitchen Gardening Seed Kits Progress in Bahawalpur in 2011, 2012 and 2013. Bahawalpur: Office of the District Agriculture (Extension) Department of Bahawalpur. Drescher AW, Jacobi P, Amend J. 2000. Urban Food Security: urban agriculture, a response to crisis?” UA Magazine, 1.1. [cited 2016 Feb 11]. Available from: www.ruaf.org/index.php?q=system/files/files/ Urban+food+security,UA+response+to+crisis.pdf Evans C, Jespersen J. 2001. Kitchen garden. “Near the House – Zones 1-2” Chap. 2, The Farmers’ Handbook (Vol. 2). [cited 2015 Feb 11]. Available from: http://permaculturenews.org/2010/01/06/farm ers-handbook/ FAO. 2010. Improving nutrition through home gardening. Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO). Available from: http://www.fao.org/ag/agn/nutri tion/household_gardens_en.stm. FAO. 2011. Food, Agriculture and Cities-Challenges of food and nutrition security, agriculture and ecosystem management in an urbanizing world. [cited 2015 Feb 4]. Available from: www.fao.org/fileadmin/templates/ FCIT/…/FoodAgriCities_Oct2011.pdf Galhena DH. 2012. Home gardens for improved food security and enhanced livelihoods in Northern Sri Lanka [Doctoral Thesis]. USA: Michigan State University. Galhena DH, Freed R, Maredia KM. 2013. Home gardens: a promising approach to enhance household food security and wellbeing. Agric Food Secur. 2:8–13. Ghazali S. 2013. House garden as a symbol of place, identity and sense of belonging for low-cost flat residents in urbanizing Malaysia. Int J Soc Sci Humanity. 3:171–175. Govt. of Pakistan. 1998. District Census Report (DCR) of Bahawalpur. Islamabad: Government of Pakistan. Govt. of Punjab. 2010. Government of the Punjab Vegetable cultivation in Punjab. Lahore: Agriculture Department, Government of the Punjab. Govt. of Punjab. 2011a. Punjab development statistics 2011. Lahore: Bureau of Statistics, Government of the Punjab. 78 M.M. Anwar et al. Govt. of Punjab. 2011b. Kitchen gardening plan of action. Lahore: Agriculture Department, Government of the Punjab. Govt. of Punjab. 2012. Kitchen gardening for Rabi 2012-13 in urban areas of Punjab. Lahore: Agriculture Department, Government of the Punjab. Govt. of Punjab. 2013. Evaluation of the scheme “UpScaling of Kitchen Gardening in Urban Areas of Punjab”. Lahore: Agriculture Department, Government of the Punjab. Halder P, Pati S. 2011. A need for paradigm shift to improve supply chain management of fruits & vegetables in India. Asian J Agric Rural Dev. 1:1–20. Hasan M 2011. Kitchen gardening fails to make impact. The News. [cited 2013 Dec 29]. Available from: http://www.thenews.com.pk/TodaysPrintDetail. aspx?ID=80209&Cat=5 Heim S, Stang J, Ireland M. 2009. A garden pilot project enhances fruit and vegetable consumption among children. J Am Diet Assoc. 109:1220–1226. Holland L. 2004. Diversity and connections in community gardens: a contribution to local sustainability. Local Environ. 9:285–305. Islam S. 2011. Kitchen gardening: 80,000 seed packets prepared for distribution programme encourages people to grow vegetables at home. [cited 2013 Dec 27]. Available from: http://tribune.com.pk/ story/252604/kitchen-gardening-80000-seed-pack ets-prepared-for-distribution Khan AS (2013). Importance of kitchen gardening highlighted. Daily The News. [cited 2014 Jan 17]. Available from: http://www.thenews.com.pk/ Todays-News-6-213760-Importance-of-kitchen-gar dening highlighted Landauer K, Brazil M. editors. 1985. Tropical Home Gardens: Selected Papers from an International Workshop at the Institute of Ecology. Japan: Padjadjaran University, Indonesia, December 1985, United Nations University Press Njuguna JM. 2013. The role of kitchen gardens in food security and nutritional diversity: a case study of workers at james finlay Kenya- Kericho. Kenya: Masters Research Project, Department of Sociology and Social Work, University of Nairobi. Nkosi S, Gumbo T, Kroll F, Rudolph M. 2014. Community gardens as a form of urban household food and income supplements in African cities: experiences in Hammanskraal. Vol. 112. Africa: Africa Institute of South Africa Briefing; p. 1–6. PTA. 2016. Telecom indicators. Pakistan Telecommunication Authority (PTA). [cited 2016 Mar 14]. Avaialble from: www.pta.gov.pk/Home/ Industry Support/Industry Report Qaiser T, Shah H, Taj S, Ali M. 2013. Impact assessment of kitchen gardening training under watershed programme. J Soc Sci. 2:62–70. Rahman FMM, Mortuza MGG, Rahman MT, Rokonuzzaman M. 2008. Food security through homestead vegetable production in the smallholder agricultural improvement project (SAIP) area. J Bangladesh Agric Univ. 6:261–269. Rani S, Khan MA, Shah H, Anjum AS. 2013. Profitability analysis of organic cauliflower, radish and turnip produce at National Agriculture Research Centre, Islamabad, Pakistan. Asian J Agric Rural Dev. 3:929–935. Rehman B, Faiza M, Qaiser T, Khan MA, Ali A, Rani S. 2013. Social attitudes towards kitchen gardening. J Soc Sci. 2:27–34. Rowe WC. 2009. “Kitchen Gardens” in Tajikistan: the economic and cultural importance of small-scale private property in a Post-Soviet society. Hum Ecol. 37:691–703. Shaheb MR, Nazrul MISarker A. 2014. Improvement of livelihood, food and nutrition security through homestead vegetables production and fruit tree management in bangladesh. J Bangladesh Agric Univ. 12:377–387. Specht K, Siebert R, Hartmann I, Freisinger UB, Sawicka M, Werner A, Thomaier S, Henckel D, Walk H, Dierich A. 2014. Urban agriculture of the future: an overview of sustainability aspects of food production in and on buildings. Agric Hum Values. 31:33–51. Talukder A, De Pee S, Taher A, Hall A, MoenchPfanner R, Bloem MW. 2001. Improving Food and Nutrition Security; homestead gardening in Bangladesh. Urban Agric Mag. 5: 45–46. Tariq A, Tabasam N, Bakhsh K, Ashfaq M, Hassan S. 2014. Food security in the context of climate change in Pakistan. Pakistan J Commerce Soc Sci. 8:540–550. Titilola OL, Abraham AO, Oladejo JA. 2012. Food consumption pattern in ogbomoso metropolis of Oyo State, Nigeria. J Agric Soc Res. 12:74–83.