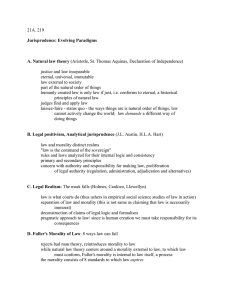

PAA JOY NATURE AND IMPORTANCE OF JURISPRUDENCE According to Professor Gower, “Academic legal training without a course in jurisprudence will be like playing Hamlet without the Prince of Denmark.” This discussion will attempt to answer the question whether the study of jurisprudence serves any purpose or to unravel the rational for studying jurisprudence. The discussion is divided into four parts. The first part which is the introductory part will deal with the concept of jurisprudence. The second part will look at the criticisms made against the study of jurisprudence. The third will focus on the importance of jurisprudence and the final section will be the concluding part. For a meaningful assessment of the relevance of jurisprudence, it is necessary to throw some light on the notion of jurisprudence. The term ‘jurisprudence’ has been ascribed various connotations in different jurisdictions. Jurisprudence in certain jurisdictions may be a reference to the philosophy of law or legal theory or theory of law, to the French, Jurisprudence is case law. Jurisprudence seeks to answer very fundamental questions such as : what is justice, rights, validity , morality. AT the centre of these is what is the nature and essence of law. Thus, to unravel what is meant by the term ‘law’. The term “jurisprudence” is a derivative from the Latin word jurisprudentia. ‘Juris’ means ‘law’ and ‘prudentia’ means wisdom. Thus, jurisprudence in its original roman sense was merely among several phrases signifying a “knowledge of the law”. Despite its original Roman conception, there is no unanimity among jurists as to the precise meaning of jurisprudence. Various meanings have been attributed to the term jurisprudence by different writers at different times. The following definitions illustrate the divergence of conceptions: John Austin in ‘The province of Jurisprudence Determined’ stated that “The science of jurisprudence…is concerned with positive law or with laws strictly so called, as considered without regard to their goodness or badness”. According to Salmond, if we use the term ‘science’ in its widest permissible sense as including the systematized knowledge of any subject of legal enquiry, we may define jurisprudence as the science of civil law. Roscoe Pound also defined jurisprudence to mean the “science of law”. i.e. an organized and critically controlled body of knowledge both of legal institutions and legal precepts and of the legal order, that is, of the legal ordering of society. For C.K. Allen, ‘Law in the making,’ jurisprudence is the scientific synthesis of laws’ essential principles. According to Paton, jurisprudence is a particular method of study, not of the law of one country but of the general notion of law itself. Lloyd has also defined jurisprudence as involving the study of general theoretical questions about the nature of laws and legal systems, about the relationship of law to justice and morality and about the social nature of law. The difficulty of definition is compounded in the case of jurisprudence by several factors. First, jurisprudence is a compendious term englobing the totality of law; and law itself is a concept that is not free from ambiguity. Secondly, jurisprudence trenches on related disciplines such as philosophy, economics, ethics, sociology, political science, anthropology, psychology, et cetera, which are necessary for comprehension of jurisprudence. Thirdly, the definitional ingredients of jurisprudence comprise law, philosophy, rights , duties, justice, morality which are in themselves either value or otherwise not free from ambiguity or controversy. The multi-faceted nature of jurisprudence has prompted Lloyd to characterize it as “a mansion with many rooms”. PAA JOY As could be seen , jurisprudence as a concept will be safer to describe than to define. It can be simply described as the philosophical underpinnings of law. Jurisprudence is concerned with the rules of external conduct of human beings , ie. rules which people are required to observe and obey. It is of necessity allied to other sciences, anthropology, psychology et ceteera. Jurisprudence assumes that in all communities which reach a certain stage of development there springs up a social machinery which we call law. Ubi societas ibi ius. In each society there is an interaction between the abstract rules, the machinery existing for their application and the life of the people. Legal systems seem to have developed for the settlement of disputes and to secure an ordered existence for the community. They still exist for those purposes but in addition they are part of the social machinery used to enable planned changes and improvements in the organization of society to take place in an ordered fashion. In order to achieve these ends, each legal system develops a certain method, an apparatus of technical words and concepts, and an institutional system which follows those methods and uses that apparatus. The pressure of social needs which law must satisfy will vary from one community to another, but jurisprudence studies the methods by which these problems are solved rather than the particular solutions. Jurisprudence is not concerned with the universalist fallacy of common rules of law, for example, the trilogy of command, duty and sanction, but seeks to construct a science which will explain the relationship between law , its concept, and the life of the community. The domain of jurisprudence is the nature of law and its purposes, the relation of legal validity to its efficacy , the interaction between law, justice and morality, the institutional and conceptual apparatus for the creation adjudication, enforcement and modification of law. The greatest reproach made against jurisprudence is that it is a maze of speculations devoid of practical value. Critics of the study of jurisprudence aver that the study of jurisprudence or the inclusion of the study of jurisprudence as part of the law school curriculum seeks to achieve noting and is an exercise in futility as its study instead of inculcating into students better approaches to the law rather lands them into an abyss of confusion. Though jurisprudence is a demanding course to take in any law school, its importance are far from criticism: In dealing with the purpose of jurisprudence, one must accept that works of jurisprudence reflect different purposes. The relevance of jurisprudence will therefore be discussed from the point view of the student of the law, the Jurist and Court, the legal Profession or the importance to the lawyer, the economy and the society in general. The relevance of jurisprudence to each of these will now be taken and dealt with seriatim. First is the student of the law. According to Lon L. Fuller in ‘The place and uses of jurisprudence in the law school curriculum” , ‘…the fundamental purpose of the course in jurisprudence should be to create in the student’s mind an awareness of problems, rather than to inculcate in him a point of view. He posits thus “If I have any object of indoctrination it is, in the words of Reed Powell, to spread the gospel that there is no gospel that will save us from the pain of deciding at every step. Our greatest danger is that we will decide issues without knowing it, that we will act on the basis of what mach called “unconscious metaphysics,” that we will accept as truisms, beyond the reach of philosophy , propositions that are in fact loaded with philosophical preconceptions. If Jurisprudence can save a tithe of our students from these intellectual hazards , it will have justified itself.” PAA JOY Jurisprudence enables the student to reflect on fundamental questions of human existence, rational and legal ordering of society and man’s place in the universe. These are philosophical questions for which jurisprudence thus provides him with a basic initiation. Again, the perplexed or indolent student might ask, “why should intending lawyers be coerced into studying philosophy?” The answer is that everybody needs and has a philosophy as the sum of his ideas and convictions. To recommend an overture of jurisprudence to philosophy is not to suggest that jurisprudence should be dominated by philosophy but that jurisprudence in ignorance of philosophy seems unsound. By giving the student an insight into the wealth of contribution of our intellectual ancestors and contemporaries, the study of jurisprudence brings theory and life into focus, broadens his horizon and accentuates his perception of basic human problems. “In jurisprudence”, Harris tells us, “ so much that was taken for granted or left unsaid about the law is put before him”. The student is brought into “acquaintance with the views of a very heterogeneous collection of theorists and philosophers…as to the deepest questions about the nature of man or society as to which …he is expected to take up an overt moral or political stance.” Again, jurisprudence not only deepens the student’s knowledge of the law by subjecting it to critical analysis but also enriches his logical faculty. Justice Holmes epigrammatic saying that “the life of the law has not been logic: it has been experience” is liable to and has often suffered misconstruction. Professor Hart has pointed out that this quotation is not a disclaimer of the relevance of logic to law. It simply means that the courts are not bound to decide cases in strict accord with the dictates of logic. The court decides cases based on the cogency of evidence presented before it through rational argument and use of language; and “an expertise in rational argument is an indispensable basis of legal practice”. The efficacy and persuasiveness of language lies in its logic. The logical faculty helps us to unravel the rationes decidendi of previous cases and to distinguish them from mere obiter dicta. In comparison with the medical doctor, it may rightly be said of the lawyer that his laboratory is his library , his theatre the courtroom ( or the classroom) , his stethoscope, his books and his drugs the language and logic of the law. By introducing the student to the various schools or theoriesst in jurisprudence, the students appreciates what each school is , and ethe relevant of each school to the study and building of the law. For instance will be able to make an informed decisions as to why a particular law is as it is and also t oquestion a particular law. For instance the sudy of jurisprudence assist student to distinguish and appraise such case like In Re Akoto , In Re Okine and Contrast same with other human irghts cases. The next is the relevance of the study of jurisprudence to the jurists or the court. Traditionally, the study of jurisprudence reflects the perspective of the judge in elaborating the knowledge about what the law is. Some cases before the courts, especially cases of first impression, raise jurisprudential questions. The case of Madzimabamuto v. Lardner –Burke [1969] AC 645 in the wake of Ian Smith’s unilateral declaration of independence of Rhodesia provides a vivid example. It raises fundamental questions of eminently jurisprudential interests. Lloyd identifies some of these questions as “what is a legal system? What is meant by ‘revolution’? Is it juridically different from a coup d’état? What is the role of a judge in such a situation? What is the relationship between validity and effectiveness? What is the relationship of laws to each other? Are all rules equally authoritative? What gives rules their authority? Is there an all-or-nothing concept of law? Is law effected by selective enforcement? What is the effect on a legal system of attention of consent? The case of Sallah v. Attorney General provided PAA JOY what Date – Bah terms “Jurisprudence’s Day in Court in Ghana”. talk about the fact that due to the little appreciation of the jurisprudential questions raised in the case, the judges failed to delve much into interrogating these jurisprudential issues. Apaloo JA for instance rejected in its entirety the attempt by counsel to impress the court with ‘Kelsen’s pure theory of law and state’. Surprisingly however, the court indirectly and unknowingly applied another theory of jurisprudence , Finnis in its reasoning and conclusion. In Nigeria also, the case of Lakanmi v. Attorney-Generalof Western Nigeria, provided a no less jurisprudential banquet. In that case, the meaning and legal effect of a coup d’état as well as the doctrine of necessity were given ample jurisprudential treatment. The classic exposition of supremacy of the American Constitution by Marshall , CJ. In Mabury v. Madison is an epitome of jurisprudential erudition and logic: “…committed to writing, if these limits may, at any time be passed by those intended to be restrained? The distinction between a government with limited and unlimited powers is obliged if those limits do not confine the persons upon whom they are imposed, and if acts prohibited and acts allowed are of equal obligation.” No less remarkable for its philosophical profundity is the reasoning of Lord Atkin in Donoghue v. Stevenson 1932] “The liability for negligence, whether you style it such or treat it as in other systems as a species of culpa, is no doubt based upon a general public sentiment of moral wrong-doing for which the offender must pay…You must take reasonable care to avoid acts or omissions which you can reasonably foresee would be likely to injure your neighbor. Who then in law is my neighbor? The answer seems to be –persons who are so closely and directly affected by my act that I ought reasonably to have them in contemplation as being so affected when I am directing my mind to the acts or omission are called in question.” Not only is an understanding of moral and political theory a prerequisite to evaluating the law and reforming it, moral and political reasoning is also frequently required in judging legal cases. This factacknowledged in one way or another by virtually all legal theorists-means that an understanding of moral and political theory is often indispensable to the resolution of legal cases. The most obvious examples (but no limited to) come from jurisdictions in which moral rights are translated into law using the mechanisms of a bill fo rights. The protections granted by bills of rights are usually framed in a very abstract and general way which can be unpacked only by moral and political theorizing. We will look ,for , instance at the South African case of President of the Republic of South Africa v Hugo (1997). In this case, the court had to interpret a provision in the South African Bill of Rights which forbids unfair discrimination on the ground of sex or gender but gives no clue as to when such discrimination will be unfair. The court had to decide whether it was unfairly discriminatory for President Mandala to pardon mothers in prison who had children younger than 12 years old but not fathers of such children. A question like this can be resolved by appeal to moral and political arguments of this kind. To the legal practitioner, the study of jurisprudence assist him in addition to seeking guidance concerning the right interpretation of substantive law to acquire knowledge which makes it easier to find arguments and develop the ability to convince. An instance is the forceful arguments made by Dr. JB DAnquah in In RE Akoto althgh the court refused to agree with him, modern udges have come to side with the noble legal practicioner Further, legal practitioners have a responsibility to promote justice and fairness in the legal system, and jurisprudence gives lawyers the skills to detect the ways in which the law may fail to reflect the demands of justice and therefore to fulfill this responsibility. An essential aspect of jurisprudence is familiarity with moral and political theory.. An understanding of moral and political theory in all its complexity alerts lawyers to the questions that need to be asked in evaluating PAA JOY proposes laws or undertaking law reform. It enables them to debate the issues in an informed, critical and analytical way, in full knowledge of the alternative views on offer. Jurisprudence has also played significant roles in the political economy of many nations. It is not beyond doubt that jurisprudence has often been used to legitimate movements of a more dubious kind this principally is the successful application of Kelsen’s pure theory of law. For instance in The State v Dosso in Pakistan as well as Uganda v Commissioner of Police , Ex Parte Matovu, the revolutions which took place all were validated by the court. The study of Juripsrudence have let court to take into account the socital interest of the citizenry and hence in modern times, will not go strictly by the logic of Kelsenite pure theory of law. This was the expression of Haynes P in the Greneda Case of Mitchell v DPP At the same time , it is clear that Utilitarianism and the development of democratic nations have been important catalysts for many works of jurisprudence . During periods of time, the ability to establish structures of power has been very central, and it is not surprising that jurisprudence has played an important role in this process. An assumption concerning a more independent purpose of jurisprudence is that it proves an indispensable means for balancing interests , that jurisprudential activates vindicate traditional values, develop fundamental principles, ensure constitutional rights, provides material for education, pursue research and support a critical and insightful debate in society. Again, jurisprudence offers a broader perspective of the law in every economic polity. Jurisprudence provides a broader perspective on the law. In asking questions about the nature of law and its point it gives us a general understanding of the relation of law to the other institutions making up our society, and its significance in relation to those institutions. For instance, jurisprudence alerts us to a variety of external perspectives on law, such as those offered by feminists, Marxists and critical race theorist. These critical perspectives aim to expose the biases of law, the interests it serves , the way in which it masks inequality and the injustices it does. Another kind of external perspective to which jurisprudence alerts us is hat offered by theorists in other disciplines such as economics and political science. These theorists claim that the law is best understood not according to its own self image-as governed by internal standards of what counts as good legal reasoning. Rather, they claim, the law is best explained as a mechanism for allocating legal rights efficiently or as driven entirely by the ideological and political mindset of judges. An understanding of critical and extra-disciplinary perspective on the law like these promotes awareness of the social and economic context in which law operates and fosters the critical cast of mind which typifies the educated lawyer. In calling attention to the fact that law is an important social practice, and not just set of rules, jurisprudence enables those who practice law, whether as solicitors, barristers , legal advisers or judges, to bring a broader perspective to their work. Decisions and actions previously guided by habit or rules of thumb will be guided instead by an awareness of the deeper issues, and by reasoning according to a broader vision of the law’s purposes. According to Peter Wahlgren in “The Purpose and Usefulness of Jurisprudence”, the many expression of jurisprudence indicate that the question about its purpose can be answered in many different ways. And that the choice of perspective will affect the conclusions that can be drawn. He suggests one such approach by looking at the purpose of each recognizable jurisprudential activity , and one of them is to investigate the characteristics of each different school of thought. By examining the characteristics of each school of thought, the student appreciates how each school views law. In so doing, the student PAA JOY gains explanations concerning the content and nature of law and thus make informed decisions and is able to contribute his quota to making laws which meet the needs and expectations of the society. Another approach suggested to identify of the purpose of jurisprudence is to try to identify one overarching purpose, which all activities more or less consciously can be assumed to fulfill. To this, Peter submits that such an approach can lead to inter alia an assumption that the primary task of jurisprudence is to provide convincing interpretations and descriptions of substantive law, and all activities can then be assumed to aim for this goal. From the foregoing, it can be said that those who assert that jurisprudence is a paper tiger is concededly subject to challenge. Indeed, the complex nature of jurisprudence may also be apprehended as a rich and vivid quest for new insights. Jurisprudence is from this point of view a paragon of pluralistic activity, in close touch with reality and with a great openness for new methods and theories , and readily assimilating new insights from other areas of society. Arguments in favour of such a positive interpretation are also the insight that a well functioning legal system must be adjusted to shifting requirements and that law is continually being affected by external factors. The many –sided nature of jurisprudence is in other words nothing but a reflection of the current development and requirements of the surrounding society. As has already been stated supra, there is widespread misconception about jurisprudence even among learned men. Jurisprudence is a broad discipline. The study of jurisprudence has obvious, if little appreciated, advantages. It not only imparts knowledge of the law but, more importantly initiates the student into philosophy, teaches him to think clearly and reason cogently. Its values for legal practice, through logic and the use of language, is also not negligible. importance of jurisprudence to the lawyer –JB Danquah’s argument in Re Akoto centrering on human rights Helps students to questions assumptions like what is law etc To the lawyer : to prevent their argumetns being described frivolous and vexatious Judges, justify the cnoclusions reached in Hard cases –like donogue v stevension. IT was novel Student –Understand a reason behind a law talk as part of the intro that in civil jurisdictions such as france jurisprudence is referred to as case law-use in terms of ‘nomenclature’ After talking about the just supra that is where you mention the fact that it seeks to answer various questions and at the heart of it is law and menintion the various theorists PAA JOY THEORIES OF LAW Different theories compete for attention in respect of answering the question what is law or what is the nature of law. These theories can roughly be classified as (but are not limited to) legal positivism and natural law. While the former contends that law as a real social phenomenon is a or may be separated from morality and should be defined exclusively with reference to social facts, the latter argues that law is so intimately connected with moral ideas that the concept of law must necessarily include a reference to morality. The question is what test must law pass so as to be accorded the title ‘law’ in a state? NATURAL LAW WHY THE NATURAL LAW THEORY According to Friedman, the history of natural law is a “tale of the search of mankind for absolute justice and truth”. Natural law theory is an attempt by human beings to find justification for why tyranny should not be permitted. Put in another way, it is an invention by human beings to establish a ‘humane’ society. As Lloyd puts it “ the essence of natural law may be said to lie in the constant assertion that there are objective moral principles which depend upon the nature of the universe and which can be discovered by reason. These principles constitute the natural law. This is valid of necessity because the rules governing correct human conduct are logically connected with immanent truths concerning human nature. Natural law is believed to be a rational foundation for moral judgement. Natural lawyers accept that natural law principles do not always have the effect that they would like them to have but they argue that the principles remain true even if they are ignored, misunderstood , abused in practice, or defied in practical thinking .” Therefore, Natural law is an aggregate of rights and obligations which flow from the characteristics of human nature. The natural law theorists are not against the state or against positive law. However to them, Positive law must respect that which is natural. This will in effect alleviate arbitrary and tyrannical rule. It has been argued therefore that natural law is antecedent both in logic and nature to the formation of civil societies and organized governments. They posit that positive law is manmade laws that have their sources only in constitution or codes, statues etc, which are unworthy of obedience. To the natural lawyers, it is the moral responsibility of the state , through the instrumentality of its positive law, to acknowledge their existence, to foster and facilitate their enjoyment by the wise and scientific implementation of the natural law with a practical and consonant code of civil rights and obligations. SOURCES OF NATURAL LAW PAA JOY Natural law draws its source from inspiration from nature that there are laws of nature according to which all things ought to behave THE PREDICATE OF NATURAL LAW THINKING There are objective moral order. It is within the scope of human virtue CHARACTER OF THE NATURAL RIGHTS AND OBLIGATIONS They are inalienable because they aer bestowed by nature : Right to life They are inherent They are universal EVOLUTION OF THE THOERY OF NATURAL LAW The Greek Period : Classical philosophy credits Greek thinkers as having laid the basis for natural law and developed its essential features. The Greeks themselves , though comparatively uninterested in the technical development of law, were much concerned in exploring its philosophical foundations, and in doingso developed many fundamental concepts ,of which natural law was one of the most important. Thus, they surmised that the universe was governed by intelligible laws capable of being grasped by the human mind. It was therefore possible to derive, from the rationality of the universe, rational principles which could be utilized to govern life in society. Before the 5th Century : Law and religion was very much the same. Law was regarded as issuing from the gods and known to mankind through revelation of the divine will. Sophocles’ Antigone: Exhibits the conflict of religious duty with the secular command. King Creon forbade the burial of polyneikes. Antigone-that in burying her brother she had brokenCReon’s law, but not the unwritten law. After the 5th Century BC: There was a change in philosophy. Philosophy moved away from religion. law ceased to be regarded as an unchanging command of a divine being. Law acquired the character of a human invention. Justice came to be examined from the social perspective rather than metaphysical. Explanation for the Change in Perception : Before the 5th BC, Greek society was predominantly agrarian, not so scientifically developed. In such society, everything is likely to be attributed to God. After 5th Century BC Greek society became more creative.-the use of the intellect to design and produce the Greek artefacts. This affected the relationship between law and religion. Therefore natural law emanating from God became law emanating from reason. Examples of Natural law thinking . Socrates (470-399 BC) and Plato (428-348 BC) argued that there were principles of morality which it was possible to discoverthrough the processes of reasoning and insight. Law based on these principles would thus be the product of correct reasoning. PAA JOY Plato:Plato by his idealist philosophy, laid the foundations for much of subsequent speculation on natural law. He developed the ‘idea’ of justice as an absolute thing-in-itself having qualities of truth and reality higher than those of positive law, which could then be seen as a mere shadow of real justice. Law must constantly strive to approximate to the Absolute Idea of justice, and ideal justice could only be achieved or fully realized in an ideal Sate ruled over by philosopher –kings capable of grasping the Absolute Idea of justice. ARISTOTLE (384-322 BC) : For Aristotle unlike Plato, the law should rule rather than man ruling. It is natural for the human being to be corrupt, exhibit the character of a beast. To Aristotle, the human being is subject to vices of the beast –greed , anger etc. Hence it is not good to let man rule ,but rather the law should rule. According to him, he who decrees that the law should rule would as well decree that God and God alone rules and he who decrees that man should rule, decrees that the beast should rule and this leads to tyranny. Aristotle recognized nature as the capacity for development inherent in particular things, aimed at a particular end or purpose ,in both physical and moral phenomena. He also made a distinction between natural and conventional justice. To him, ‘natural justice’ is common to all humankind and based on the fundamental end or purpose of human beings as social and political beings, which he concludes to be the attainment of a ‘state of goodness’. Conventional justice varies from State to State in accordance with the history and needs of particular human communities. The Stoics: They identified Nature with Reason, arguing that reason governs all parts of the universe, and that humans, as part of the universe and of Nature, are also governed by Reason. Thus, to the Stoics, reason as a universal force pervading the whole cosmos was considered by the Stoics as the basis of law and justice. People will therefore live ‘naturally’ if they lived according to their Reason. The Roman Period:They were influenced by the Stoic. The Romans knew that certain things do not conform to natural law but exist in the Roman society and that there were certain laws which did not conform to natural law but peculiar to the world at large. They came out with the three ideas of law : Ius civille : the law peculiar to the Roman State Ius gentium : the law common to all nations Ius naturralle : natural law Cicero (106-43 BC) : He argued that nature provided rules by which humankind ought to live and that these rules, which could be discovered through Reason, should form the basis of all law. He established the view that an unjust law is not law and argued that a test of good law was whether it accorded with the dictates of Nature. THE MIDDLE AGES AND SCHOLASTICISIM This was an attempt to bring secular philosophy , especially Aristotelianism, into harmony with religious dogma. That was a period when the church got intense competition with the Roman State for superiority. It was therefore a period dominated by the philosophers of the Catholic Church. ST. AUGUSTINE: Before the fall of man, there was the golden age of mankind in which an absolute ideal of the law of nature was in place. After the fall of man , man was forced down to the CIVITAS TERRENA PAA JOY where man became vulnerable and of evil predispositions-government, law, property and the state to organize us to go back to God. If so, who must be obeyed? The king or the church? Role of the Church : Notwithstanding the fall, men hope to return to the kingdoms of God after our stay here. The Church becomes the guardian of eternal law of God here on earth to guide us on our journey back to God. Role of Government : Government therefore in the promulgating of the worldly law –lex temporalismust strive to fulfill the demands of the eternal law –lex Aeterna. The lex Aerterna is therefore superior to the lex temporalis . The lex aeterna resides resides in the church. St. Thomas Aquinas (1224-74):Aquinasdivided law into four categories: Lex aerterna –eternal law:This is law which constitutes God’s rational guidance of all created things and is derived from the divine wisdom and based on a divine plan. Divine Law-Lex divina (Revealed in Scriptures): that part of eternal law which is manifested through the revelations in the Christian scriptures Natural Law (Discovered through human reason): which describes the participation of rational creatures in the eternal law through the operation of reason. Human Law –Lex humana (essence is to be just) : which is derived from both Divine law and Natural law and which is, or must be directed towards the attainment of the common good. This law may be variable in accordance with the time and circumstances in which it is formulated, but its essence is to be just. Thus lex injusta non est lex (an unjust law is not law). For Aquinas, a human law would be unjust where it : furthers the interests of the law giver only; exceeds the powers of the law giver; imposes burdens unequally on the governed Under these circumstances, then , disobedience to an unjust law becomes a duty. However, such disobedience though justified , should be avoided where its effects would be to lead to social instability, which is a greater evil than the existence of an unjust law. CATALYSTS OF THE PERIOD Renaissance Reformation : attack by Protestantism in the 16th Century on the dominance of the Church. Equality in the Bible interpreted to imply equality of all before God and that all have the right to commune with God without the intervention of a priest. As a result, the existing order came under attack : There was an attack on the catholic church as the only church. There was a collapse of the economic system based on feudalism PAA JOY Feudalism also collapsed in its political form. CLASSICAL ERA OF NATURAL LAW Medieval Period was dominated by Scholarsticism. The Church was pre-eminent The Church was the dominant source of knowledge NATURE OF ATTACK ON EXISTING ORDER Against the monolithsism of Catholicism Against the economic system based on feudalism Politically against the feudal system that supported nobility and privileges:why should governance be only the reserve of the noble. ESSENTIAL CHARACTERISTICS OF CLASSICAL NATURAL LAW Intensified the divorce of law from theology. Natural law was infused with the doctrines of theology. Natural law note limited to mere first principles but extended to concrete and detailed rules. Thus, it became decentralized-universal. Notion of the social nature of man gave way to individualism There was a shift from theological to a casual view etc. Thus, natural law was not static. THEORY OF SOCIAL CONTRACT For Hobbes, in the state of nature man is an essentially social an gregarious being but intrinsically selfish, malicious , brutal and aggressive. Hobbes background was full of turmoil. He lived in a period of turmoil. He supported a strong sovereign who should impose his will on the people. To him , if we want peace in the society, we need to have a monarch that is absolute and once this is done, no law can be unjust. There is one caveat “ everybody possesses the natural right to preserve his life and limbs against the aggression of others. To Hobbes, Iniquitous and tyrannical laws must be obeyed. To him , if the king becomes dictatorial, he will suffer “ the pain of eternal death”. One situation when duty of loyalty to ruler is exempt-when the sovereign has lost the power to preserve the peace in society and to protect the safety of citizens JOHN LOCKE PAA JOY He talks of the state of nature as a peaceful place where everybody is a king or queen with everything in abundance. There was however one aspect of the gift of nature. According to him, when you miss your sweat to the gift of nature, it becomes your property. This may lead to accumulation, leading further to competition. And that there is the need for us to manage ourselves to al benefit from the state of nature. So according to him, the people will enter into an agreement with themselves and surrender their individual sovereign right to the community.Here, everybody was a sovereign . But according to Hobbes, in entering into the contract with him, there are certain inherent right, -the natural rights to life, liberty and property . THREE CONTRACTS pactum Unionis : Pactum Subjecionis Conract by the king in turn the Amercian declaration of independence is a replica of John Locke’s theory . John sought to give justification for the existence of the sovereign and the new emerging capitalist class ROUSSEAU Pactum Unionnis but the sovereign rights remain with the people . Hence republicanism –thus sovereign authority resides in the people where the president presides. (remember the preamble to the 1992 Constitution of Ghana) PRACTICAL ACHIEVEMETNS OF NATURAL LAW Established the basis for the connection between law and the values of freedom, justice, equality etc. Set the tone for a disconnection governance e which has the sole purpose of guaranteeing the welfare of the people on the one hand and arbitrary rule on the other –eg. ideas of John locke, Rousseau , Montesquieu Remember the preamble to the Constitution (the effect on Constitutions of nations) Human rights protection-the philosophical justification of human rights takes from natural law Remember the Nuremberg trials under international law (the accused persons obeyed laws made by the existing authorities at that time so whey should they be penalized.” Provided the legal instruments by which the liberation of the individual from medieval ties was achieved led to religious liberty, freedom of movement purged the criminal law of its dehumanizing aspects eg. torture ,dehumanizing punishment etc. Remember also audi alteram partem, Inspired revolutions leading to liberal constitutions –American and French what in your view has been the influence of natural law on the Ghanaian society? PAA JOY DECLINE OF NATURAL LAW Hostility against the Social Contract Because of its association with revolution it was regarded as politically dangerous . For Bentham, you cannot compare the king to anyone else and that the idea of natural law was politically dangerous. Development of empiricism of the 19th Century Europe derogated from the theory Hostility against the natural law the growth of scientific research deepened empiricism –sheer belief was disapproved Appreciation of relativity of morality and moral standards Emergence of new theories of man’s evolution –leading to ideas that man is continually improving e.g. Darwin’s theory The historical school led by Sir Henry Maine doubted the assertion that private liberty and equality existed in the state of nature. MONTESQUIEU AND HUME The social contract did not survive the 18th Century . One of the reason was the change individualistic conception of society to collective conception stimulated by a rising tide of nationalism. Another reason was the stupendous growth of natural science which gave strength and emphasis to empirical methods against deductive methods. Also, the European society demanded a comparative and sociological approach to the problems of society not an abstract one. It is maintained that Montesquieu and Hume destroyed the foundations of natural law. Montesquieu (189-1755) in his book Spirit des Lois, Montesquieu introduced a new approach to law. He superficially adhered to the law of nature. For him law means the necessary relations arising from the nature of things. He emphasized that there was a standard of absolute justice prior to positive law. He maintained that law although vaguely based on some principles of natural law must be influenced by environment and conditions such as climate, soil, religion, customs, commerce, etc. David Hume (1711-1776) Hume launched an attack on the reasoning adopted by natural law in that the attempt to derive an ‘ought’ form an ‘is’ is flawed. for example Asare is a dog; Asare is black; all doges called Asare ought to be black. This deduction although logical is flawed for not all doges called Asare ought to be black. He argued that the process of law creation and enactment had nothing whatsoever to do with morality or the principles of natural law. The logical conclusion of his argument is therefore that natural law must be rejected as it is contrary to empirical and observable truth. Modern variants of natural law what factors accounted for the interest in natural law? PAA JOY There are many reasons-but the most fundamental reason for the revival of interest in the neo natural law was the 2nd world war. Raz was a positivist but after the war he blamed himself for the Nazis war-his idea of a special race, a superior race and the fact that the rest should be eliminated was brutish so he changed to a neonaturalist. After the 2nd world war, philosophers started to ask how they contributed to the Nazi system. The Soldiers who carried out the ethnic cleansing were to be punished but the question was how to punish them since they were obeying the law ie. Those who obeyed Hitler. At the Nuremburg trials, the world decided tha they should be punished and that the laws that they obeyed were not laws . They therefore resorted to natural law in order to be able to punish them. By resorting to natural law, they knew that there were certain laws that must not be obeyed even if they were decreed by the king. And if obeyed, you will be punished for it. That there must be certain standards for making and obeying laws. Hitler’s acts drewe the world’s attention to human rights . Human rights has its foundation in natural law. That any law that infringes on the innate qualities of man was not law. Natural law was a solution to the world problem-ie. The infringement on human rights-that was in existence. It was replaced with the earlier principles of natural law. Before the 2nd world war, there was limited protection of human rights. But after the 2nd world war, protection of human rights became a world concern. LON L FULLER He was a professor of professor of jurisprudence at Harvard University from 1948-1972. Fuller is regarded as the leading contemporary natural law theorist. His theory lacks the metaphysical structure of natural law. He was more concerned with the overall working of the legal system and stressed on the difficulty of evaluating the individual will. He blamed the totalitarianism f 1930s and 40s on failure to make laws. His theory is one of ‘procedural’ natural law. His theory is affiliated with themes of an interest in discovering principles of social order which the lawmaker must take into account if he is to be successful at his task and a stress on the role of reason in the law making process. He asked a question-what is a legal system? What is a legal system? he believed that if certain steps are followed in making law, then automatically once those steps are followed, then we will have good law and the good law will be in conformity with the natural law. he also asked –What are the minimum requirements of a legal system He wrote a book called ‘the morality of law’ and in the book his principal concern was stated by him as follows “ the content of these chapters has been chiefly shaped by a dissatisfaction with the existing literature concerning the relation between law and morality.” –The existing literature was positivist law – law is distinct from morality Chapter two of his book was titled the Morality That Makes Law Possible. He believed that in law, there is some notion of morality . That law cannot be separate from morals and that there is essentially a set of minimum criteria for recognizable legislative that need to be followed. Under the old law system, the content of the law determined the validity of the law. However he was concerned with the procedures that have to be followed before a law is made. Procedures that it followed would lead to the best law being made. the ‘inner morality of law’ is the procedural requirements that should be satisfied to create and maintain a system which can be properly called a ‘legal system’. “ What I have called the internal morality of law is in this sense a procedural version of natural law…” The eight negative procedures are as follows : PAA JOY Failure to establish rules at all , leading to absolute uncertainty. That is there should be rule since the first place as supposed to a series of ad hoc judgments. Failure to make rules public to those required to observe them Improper use of retroactive lawmaking : The people would have to ask themselves if they had broken the laws. You cannot make laws for people to be punished for what they did before the laws were made Failure to make comprehensible rules . the rules should be understandable. Making rules which contradict each other. They should be consistent. Making rules which impose requirements with which compliance is impossible. Changing rules so frequently that the required conduct become wholly unclear. Discontinuity between the stated content of rules and their administration in practice. that is the administration doing something else and expecting others to do the other. Fuller characterizes these conditions as the morality hat makes the law possible. While, Aquinas’ theory centers on external morality of which the law must conform to, Fuller’s legal morality is internal to the law itself. Failure to respect any of the procedures of legal morality result in a legal system that is not properly called. The ‘natural law’ element in Fuller’s writing reflects his concern with legality or due process rather than concern with the substance or content o the laws. Internal morality is a set of criteria whereby a legal order may be evaluated –constitutes a series of guidelines, or ideals, to which a legal system should aspire. Fuller distinguished two moralities ; a morality of duty and a morality of aspiration. that law is not just law. It has an inner aspect. “…it embraces a morality of duty and a morality of aspiration. It confronts us with the problem of knowing where to draw the boundary below which men will be condemned for failure, but expect no praise for success…” Certain things are moral of a morality of aspiration as supposed to a morality of duty such as achieving excellence in a subject. Golding does not accept this explanation because he says it involves an overextension of the term morality. Fuller in his book ‘anatomy of law’ refers to the conditions of success in lawmaking enterprise as being ‘implicit laws’. Golding thinks it is not incorrect to characterize these as moral guidelines for lawmakers and officials, if they are to act in a fair and responsible fashion towards the member of society. Fuller’s argument is part of what is meant by rule of law and just administration of laws. Adherents to it will lessen arbitrary treatment of the public by law-makers and law-appliers. It may be incorrect to characterize these guidelines as ‘internal’ to the law, for they are derived from the nature of the enterprise of lawmaking. Goldign is of the view that adherence to these guidelines does not entirely rule out the possibility of laws that are bad or unjust according to some substantive (external) standard. Fuller however shows that there is an intricate connection between the questions of existence of law and obligation. PAA JOY HART-FULLER DEBATE The debate was sparked by an article written in the Harvard Law Review by Professor Hart in 1958. Professor Fuller responded in an article in the same journal. Hart replied in a chapter in The Concept of law in 1961. Fuller responded in a chapter in his The Morality of Law in 1963. Hart replied in an article in 1967. The pivot , or at least the common starting –point , in the debate was the attitude taken by Gustav Radbruch to the legality of laws passed during the Nazi era in Germany. Radbruch had originally been a positivist, holding that resistance to law was a matter for personal conscience, the validity of a law depending in no way on its content. However, the atrocities of the Nazi regime compelled him to think again. He noted the way in which obedience to posited law by the legal profession had assisted the preparation of the horrors of the Nazi regime, and reached the conclusion that no law could be regarded as valid if it contravened certain basic principles of morality. After the war, it was this thinking that was followed in the trials of those responsible for war crimes , or who had acted as informers for the former regime. In 1949, a woman was prosecuted in a West German court for an offence under the German Criminal Code of 1871, that of depriving a person illegally of his freedom, the offence having been committed, it was claimed , by her having denounced her husband to the war-time Nazi authorities as having made insulting remarks about Hitler, while on leave from the army. (The husband was found guilty and sentenced to death, but not executed, and sent to the eastern front). The woman , in defence, claimed that her action had not been illegal since her husband’s conduct had contravened a law prohibiting the making of statements detrimental to the government-a law that , having been made according to the constitution in place at the time, was valid. The court found that the Nazi statute, being ‘contrary to the sound conscience and sense of justice of all decent human beings’, did not have a legality that could support the woman’s defence, and she was found guilty. The case thus illustrated a conflict between positivism and natural law, the latter triumphing. The principle adopted in the decision was followed in many later cases.-Positivissm : Tinieye v Republic –per Taylor; Re Akoto; In Re Okine ; Naturalist: Ex parte Quaye Mensah ; NPp v IGP ; Npp v GBC ; 31st December Case ; Patience Arthur v Moses Arthur PROFESSOR FULLER’S CASE Professor Fuller (unlike Hart) believes that the German courts were correct in their approach. In the article (the 1958 article) that expresses this view, Fuller introduces us to the notion of ‘fidelity to law’. At first it seems that Fuller is saying that ‘fidelity to law’ is something that exists. We may find this puzzling in view of the evidence that some people ,ranging from petty criminals to revolutionaries, do not have feelings of fidelity to law. It transpires, however, that Fuller is using the notion as a lead-in to mentioning that a legal system must have certain characteristics if it is to command the fidelity of a right-thinking person. Foremost among these characteristics is respect for what Fuller calls the “inner morality of law”. By this Fuller refers to the essential requirement of a legal system that it should provide coherence, logic , order. These characteristics were lacking in the system of government instituted by the Nazis, as Fuller illustrates by reference to the retroactive decree by which thee murder of 70 people in the Roehm purge of 1934 was validated, an event ‘demonstrating the general debasement and perversion of all forms of social order that occurred under the Nazi rule’. PAA JOY Professor Fuller proposes that a system of government that lack what he terms of the ‘inner morality of law’ cannot constitute a legal system, the system lacking the very characteristic-order-that is sine qua non of a legal system. In his book, Morality of Law, published in 1963, Fuller turns from the negative to the positive and explains what characteristics a system must show in order to be capable of constituting a legal system. He begins his explanation with an allegory about ‘the unhappy reign of a monarch who bore the convenient, but not very imaginative and not very regal sounding name of Rex’. Rex was determined to reform his country’s legal system, in which procedures were cumbersome, remedies expensive, the language of the law archaic and the judges sometimes corrupt. His first step was to repeal all existing laws and to set about replacing these with a new code. But , inexperienced in such matters he found himself incapable of formulating the general principles necessary to cover specific problems and, dishearten , gave up the attempt. Instead he announced that in future he would decide all disputes that arose himself. He accordingly heard numerous cases but it became clear that no pattern was to be discerned runningthrough the judgments that he handed down. The confusion that ensued caused the fiasco to be abandoned. Next , Rex resolved that reform should be achieved by his deciding at the beginning of each year all the cases that had arisen during the preceding year. This method would enable him to act with the benefit of hindsight. His rulings would be accompanied by his reasons for making them. But ,since his object was to act with the benefit of hindsight, it was to be understood that reasons given for deciding previous cases were not to be regarded as necessarily applying to future cases. After his subjects had explained that they needed to know in advance the principles according to which decisions would be made out the rules by which future disputes would be determined and after further labors a new code was published. But when the code was finally published, Rex’s subjects weredismayed to find that its obscurity was such that no part could be understood either by laymen or lawyers. To overcome this defect Rex ordered a team of experts to revise the code so as to leave the substance intact but clarify the wording so that the meaning was clear to all. However, when this was accomplished it became evident that the code was a mass of contradictions, each provision being nullified by some other. Undeterred by this latest failure, Rex ordered that the code should be revised to remove the previous contradictions , and that at the same time the penalties for criminal offences should be increased, and the list of offences enlarged. This was done, and it was made, for example, a crime punishable by ten years’ imprisonment to cough, sneeze, hiccup, faint or fall down in the presence of the king. Failure to understand, believein, and correctly profess the doctrine of evolutionary, democratic redemption was made treason. The near revolution that resulted when the code was published caused Rex to order its withdrawal. Once again a revision was undertaken. The new code was a masterpiece of draftsmanship. It was consistent, clear, required nothing that could not reasonably be complied with, and was distributed free. However, by the time that the new code came into operation its provisions had been overtaken by events. To bring the code into line with current needs, amendments had to be issued daily. PAA JOY With time the number of amendments began to diminish and public discontent to ease. But before this had happened Rex announced that he was resuming the sole judicial role in the country: all cases would be tried by himself. At first all went well. His decisions indicated the principles that had guided him, and those by which future issues would be determined. At last a coherent body of law seemed to be appearing. But with time, as the volumes of Rex’s judgments were published, it became clear that there was no link between Rex’s decision and the provisions of the code. Leading citizens met to discuss what should be done but before any decision was reached Rex died, ‘old before his time and deeply disillusioned with his subjects’. THE INNER MORALITY OF LAW Corresponding to the eight defects illustrated by Rex’s mistakes, Fuller lists eight qualities of excellence. In a legal system the laws must be : General (not made ad hoc); 2. Published; 3. Prospective, not retroactive; 4. Intelligible; 5. Consistent; 6. Capable of being complied with; 7. Endure without undue change; 8. Applied in the administration of the society. These qualities make up the ‘inner administration of the society. These qualities make up the ‘inner morality of law’. The word ‘morality’ is misleading. The word carries ethical connotations, yet none are intended. What Fuller refers to is the inner character of a legal system the characteristics without which a system cannot properly be regarded as a legal system. The phrase also used by Fuller, ‘fidelity to law’, reflects the notion that a citizen can owe a duty to obey only where the features that make up the inner morality of law are present. Does Fuller’s view that a system of government that lacks the ‘inner morality of law’ can command no allegiancefrom a citizen mean that Fuller is to be regarded as a natural lawyer? In one sense Fuller stands outside the natural law camp. Imaging a law that required all children of ten who were lefthanded to be executed. To a natural lawyer the law would, be in conflict with a code higher than manmade decrees, be void. Yet the law would not conflict with any of the Fuller requirements: the law would display the inner morality of law. So for Fuller, the law would, we must presume , be valid. In this sense Fuller stands as a positivist. And yet the flavour of natural law hangs about him. Consider the passage: ‘To me there is nothing shocking in saying that a dictator-ship which clothes itself with a tinsel of legal form can so far depart from the morality of order, from the inner morality of law itself, that it ceases to be a legal system. When a system calling itself law is predicated upon a general disregard by judges of the terms of the laws they purport to enforce, when this system habitually cures its legal irregularities, even the grossest , by retroactive statutes, when it has only to resort to forays of terror in the streets, which no one dares challenge, in order toescape even those scant restraints imposed by the pretence of legality-when all these things have become true of a dictatorship, it is not hard for me, at least, to deny to it the name of law.’ Here and elsewhere in his writing we gain the impression that it is not so much the failure to observe the inner morality of law that sticks in Fuller’s throat as the evil that in practice results from this failure. Be that as it may, what we can say is this: under mainstream natural law thinking a law is nota valid law if it conflicts with a higher moral code. For Fuller, a law is not valid if it forms part of a purported legal system that fails to comply with a higher code, the code in Fuller’s case, however being one based not on ethical values, but on values stemming from rationality. In this sense, in that he judges a law’s validity by reference to an outside standard, Fuller’s thinking can fairly be regarded as forming a strand in the natural law tradition. PAA JOY Remember Tsikata in Relation to Articles 19(5) and (7) PROFESSOR HART’S CASE Professor Hart’s point of divergence form Fuller is over the Radbruch issue. Hart, the positivist, rejects the notion that because of the circumstances in which it was made, a Nazi law should be deemed invalid. Is Hart by so doing in effect endorsing the legality of what may be wholly evil? NO., Hart explains, he is not. People who claim that a posited law is not valid because it fails to meet certain external criteria muddy the water. The positivist approach makes people face up to the real issue. The positivist confronts people with the question –‘That law is the law. Is it so evil that you intend to disobey and suffer the consequences?’ ‘This’ Hart says ‘is a moral [question] which everyone can understand and it makes an immediate and obvious claim to moral attention. If, on the other hand, we formulate our objection as an assertion that these evil things are not law, here is an assertion which many people do not believe, and if they are disposed to consider it at all, it would seem to raise a whole host of philosophical issues before it can be accepted.’ The natural lawyer blurs the issue. If we are going to criticsinstitutions or laws we ought to do so by speaking plainly and facing reality, not basing ourcriticisms on ‘propositions of a disputable philosophy. In The Concept of Law Hart, in a powerful plea , restates this point , ‘So long as human beings can gain sufficient co-operation from some to enable them to dominate others, they will use the forms of law as one of their instruments. Wicked men will enact wicked rules which others will enforce. What surely is most needed in order to make men clear sighted in confronting the official abuse of power, is that they should preserve the sense that the certification of somethingas legally valid is not conclusive of the question of obedience, and that, however great the aura of majesty or authority which the official system may have, its demands must in the end be submitted to a moral scrutiny. This sense, that there is something outside the official system, by reference to which in the last resort the individual must solve his problems of obedience, is surely more likely to be kept alive among those who are accustomed to think that rules of law may be iniquitous, than among those who think that nothing iniquitous can anywhere have the status of law.’ It is an irony of the Hart-Fuller debate that in deciding how, after the war, cases such as those concerning ‘grudge informer’ cases should have been dealt with , both Hart and Fuller believe that (as also had Gustav Radbruch) retrospective legislation should have been the answer. But Fuller’s reasons differed from those of Hart. ‘But as an actual solution for the informer cases, I,’ Fuller wrote, ‘like Professors Hart and Radbruch, would have preferred a retroactive statute. My reason for this preference is not that this is the most nearly lawful way of making unlawful what was once law. Rather I would see such a statute as a way of symbolising a sharp break with the past, as a means of isolating a kind of clean –up operation form the normal functioning of the judicial process. By this isolation it would become possible for the judiciary to return more rapidly to a condition in which the demands of legal morality could be given proper respect.’ PAA JOY POSITIVISM Positivism is not a united front. There are various propositions. Even though they do not have unity, there is a common ground. One of the common points is that the letter of the law is important more than the spirit. Thus, the words that are written and their literal meaning represent what the law is. It means that there should not be any external matters read into the provision. Secondly, what is written down is key to defining law. Thus, law is what has been posited or written down. They are not interested in our personal thoughts but what is written down. Positivists have argued that there is a distinction between law and morality (separation thesis). In other words law and morality are not fused. This among other things is to ensure predictability and certainty of the law otherwise the law will be countered by morality. Positivists believe that law is a creation of a law giver (a human law giver) who is not ‘God’. This is the general first idea. Because it is a human law giver, it is said that law is the work of parliament, monarchs or rulers (human rulers-presidents, prime ministers). It can then be said that law is from legislation and judicial precedents (if you conceive the whole concept of ruler – looking at the government as a whole: executive, legislature and judiciary). Because of that it is said that there is a ‘known human author’ of law. Either a King, Parliament etc. Positivists suggest that law is a product designed by human mind. Fundamental to this is that , law is a matter of ‘social fact’. The meaning according to positivists is that law is found in actual practices or institutions of a state. All these can be summarized into five points: Law is a creature or creation of human agents. Because it is a creation of human agents, we are talking about law as it is not law as it ought to be. If you will do this, then it is said that law is found in rules declared by authorities. Hence unless the authority such as Parliament declares the law, it is not law. Positivist believe that there is a formal criteria to determine the validity of law. Look at Article 106 of the Constitution in the case of Ghana for instance. There is no necessary connection between law and morality-separation thesis. Law , to the legal positivist, is a social fact, “ a particular way of structuring social life. It is thus essential to the nature of law that it can be identified without any appeal to controversial moral arguments. The PAA JOY positivists suggest that once the law has fulfilled the formal criteria, the law becomes law proper and that it is not at all times that the law may have a moral interface. That is to say that sometimes, the law might contain some moral precepts. However as has been stated supra, that amount of morality will not determine the validity of the law and rather it should have fulfilled the formal criteria. The second point under the fifth is that the law itself may include a moral test and the ‘moral test’ is that ‘for a law to be valid, it must contain the following things… (which may include morality)’. This is what is called positive morality-the legislated morality. That is morality that is allowed to be part of law by virtue of legislation. The third point is that courts or judges may be authorized to dispense justice on a particular notion of morality-See Article 296 , Article 23. Here the judges can only do that unless they are authorized by law. Finally, law sometimes have the ‘open texture language’: This is the open text of the provision. So here the judge has discretion to look at the moral aspect of the provision. All these show that although there is no necessary connection between law and morality, there are however some exceptions. Hart makes the separation thesis clear by maintaining that there is “the need to distinguish, firmly and with the maximum of clarity , law as it is from law as it ought to be”. Austin puts it : “ The existence of law is one thing; its merit or demerit is another. Whether it be or be not is one inquiry; whether it be or be not conformable to an assumed standard, is a different enquiry. A law, which actually exists, is a law , though we happen to dislike it, or though it vary form the text, which we regulate our approbation and disapprobation.” Consistent with this position is the legal and political philosophy of Joseph Raz. For him, when there is legal system and laws, “the courts are bound to apply them] regardless of their merit… Legal systems find their application undesirable, all things considered”. He defends positivists conceptual independence from morality. Morality is necessarily excluded from Law. Law is to be identified by empirical social facts, namely, the common legal resources such as legislation, judicial decisions and custom, and should therefore be defeind without reference to mroal standards. This resonates well with Hart’s conception that the belief of the judges do not count when it comes to validity of the law. Law is law even if judges accept the rules of their jurisdiction for other reasons, such as “calculations of long-term interest; disinterested interest in orders; an unreflecting inherited or traditional attitude; or mere wish to do as others do”. “Legal positivism is the thesis that the existence and content of law depends on social facts and not on its merits. The English jurist John Austin (1970-1859) formulated it thus : “ The existence of law is one thing; its merit and demerit another. Whether it be or be not is one enquiry; whether it be or be not conformable to an assumed standard is a different enquiry.” The positivist thesis does not say that law’s merit are unintelligible , unimportant , or peripheral to the philosophy of law. It says that they do not determine whether laws or legal systems exist. Whether a society has a legal system depends on the presence of certain structures of .governance, not on the extent to which it satisfies ideals of justice, democracy, or the rule of PAA JOY law. What laws are in force in that system depends on what social standards its officials recognize as authoritative ; for example, legislative enactments, judicial decisions, or social customs . The fact that a policy would be just wise, efficient ,or prudent is never sufficient reason for thinking that it is actually the law, and the fact that it is unjust, unwise, inefficient or imprudent is never sufficient reason for doubting it. According to positivism, law is a matter of what has been posited (ordered , decided, practiced, tolerated, etc); as we might say in a more modern idiom, positivism is the view that the law is a social construction.” AUGUSTE CONTE He has been attributed ‘the First true positivist’. He believed that the world evolved in three stages-theology, metaphysics and Scientific. Conte like all positivist believe in ‘Empiricism- the truthfulness of a thing can be established only by experience or scientific fact. Firstly, he believes in the divine authority. So the power to govern, human rights all originate from the divine authority. The problem however is that not all of us believe in this divine authority. The metaphysics, thus the French revolution brought about ‘Natural rights’. Natural rights here becomes the basis for power and not God. Metaphysics however is a matter f abstract reasoning. Because of this problem of abstract reasoning, the Scientist-the modern era, argued that we should believe in things that we can see, verify, established by facts. The basis of positivists is scientific enquiry. THOMAS HOBBES He was dismayed by the English Civil War of 1642-1649-the struggle between Parliament and the Royals. In that Civil War, Charles I was executed. According to Hobbes, whether Parliament or Royals, there should be a strong central government.He therefore wrote a book the ‘Leviatham’. This book was published in 1651. It is in this book that he made the proposal about the ‘strong central government’. Note that Hobbes did not ask for ‘arbitral’ power but ‘absolute’ power and absolute power is to secure the wellbeing of the citizens. He believes in Royal absolutism. He thinks that law in such a state is the will of the monarch. It is from Hobbes that we get the phrase the ‘uncommanded commander’. According to him the will of the uncommanded commander is law. (it did not originate from Austin). He suggest that there will be a perpetual conflict in a state if human beings do not subject themselves to the will of this absolute ruler. In effect, his will is law. JEREMY BENTHAM He is the greatest historical figure in British legal positivism. According to Bentham , law is the expressed will of the sovereign (remember Austin got his ideas from Bentham). He wrote a book ‘Of Laws In General.’ He accepts Hobbes and argues that when such a law is expressed, it becomes law. He dismissed the idea that there is a notion of a ‘higher law’. He does not accept the higher law because he PAA JOY thinks that we have the power to determine what is good for us and that we just leave it for the sovereign to determine it. JOHN AUSTIN He was a neighbor to John Bentham and James Mill. In 1832 , fifty years after Bentham’s book ‘Of Laws In General’, Austin published his first book ‘The Province of Jurisprudence Determined’. It was a series of lectures he had delivered in University of London between 182932. In that book, Austin carried the ideas of the forefathers (Conte; Hobbes; Bentham). For academic discourse, Austin has been described as ‘Bentham’s intellectual clown’. Austin embraced law as a sovereign command ( Bentham also said the will of the sovereign.). For Austin, law comprises of the commands of a political sovereign supported by sanctions of those who are expected to obey. It should be noted that he uses a political sovereign and not a ‘legal sovereign’. Austin, it would seem , was by no means the originator of this idea of law being the command of the sovereign. Indeed, John Erskine, a Scottish natural lawyer wrote in his Pricniples of the Law of Scotland, 1759, that “Law is the command of a soverign, containing a common rule of the life of his subjects.”1 However it was Austin who maintained a more expansive version of this command theory of law to include the habit of obedience and threat of sanctions, an aspect which later generated fierce opposition. From his definition, of law , we have a trilogy : Political sovereign Commands and Sanctions Once these are present, the question of what is the nature of law is summarily but appropriately answered.2 Political Sovereign:Sovereignty exits , Austin says, where the bulk of a given political society are in the habit of obedience to a determinate common superior , and that common superior is not habitually obedient to a determinate human superior. He amplifies certain aspects of this concept. The common superior must be ‘determinate’. A body of person is ‘determinate’ if ‘all the persons who compose it are determined and assignable’. Determinate bodies are of two kinds. In one kind the ‘body is composed of persons determined specifically or individually, or determined by characters or other description respectively appropriate to themselves’. ( In this category would e placed a sovereign such as ‘the king’. In the other kind the body ‘comprises all the persons who belong to a given class…In other words, every person who answers to a given generic description…is…a member of the determinate body.’ (In this category could be placed a sovereign such as a supreme legislative assembly.) Austin thus, 1 2 Atupare … Atupare : Constitutional Justice in Africa PAA JOY does not accept ‘customary law’ positive law because there is no determinate sovereign. For him, customary law is a product of generally held opinions of an indeterminate community of persons. The society must be in ‘the habit of obedience’. If obedience ‘be rare or transient and not habitual or permanent’ the relationship of sovereignty and subjection is not created and no sovereignty exists ( But isolated acts of disobedience will not preclude the existence of sovereignty . The policy consideration of Austin on this point is that it is one of the cardinal principles of a functioning society that the political sovereign is habitually obeyed. Disobedience will lead to a ‘state of nature’. Austin asks : What will you call a state which is torn apart in worrying factions? According to him, in such a state , the original sovereign is lost and that there are two new sovereigns. An instance is the US civil law between 18611865 between the Union and the Confederacy. ‘…habitual obedience must be rendered by the generality or bulk of the members of a society to …one and the same determinate person , or determinate body of persons .’ (For example: in case a given society be torn by intestine war, and in case the conflicting parties be nearly balanced, the given society is in one of two positions. If the bulk of each of the parties be in a habit of obedience to its head, the given society is broken into tow or more societies. If the bulk of each of the parties be not in the at habit of obedience, the given society is simply or absolutely in a state of nature or anarchy . It is either resolved into its individual elements , or into numerous societies of an extremely limited size: of a size so extremely limited , that they could hardly be styled societies independent and political.’ The common determinate superior to whom the bulk of the society renders habitual obedience must not himself be habitually obedient to a determinate human superior. ‘He may render occasional submission to commands of determinate parties. But het society is not independent …if that certain superior habitually obeys the commands of a certain person or body…Let us suppose, for example, that a viceroy obeys habitually the author of his delegated powers. And, to render the example complete , let us suppose that eth viceroy receives habitual obedience from the generality or bulk of the persons who inhabit his province. The viceroy is not sovereign within the limits of his province, nor are he and its inhabitants an independent political society. The viceroy , and (through the viceroy) the generality or bulk of is inhabitants, are habitually obedient or submissive to het sovereign of a larger society He and the inhabitants of his province are a society political but subordinate..’ So the mere fact that you may exercise some amount of political power in a state does not make you a sovereign. –remember the practice in a Federal State where the state government obey the Federal government and the laws of the state government is subject to that of the federal government. The power of the sovereign is incapable of legal limitation. ‘Supreme power limited by positive law is a flat contradiction in terms.’ But what of the position of a sovereign in relation to a society’s constitution? May a body be sovereign of a sovereign in relation to a society’s constitution? May a body be sovereign yet subject to the constitutional law? Austin answers, no. A sovereign is subject to no legal limitation. He explains that : ‘…when we style an act of a sovereign an unconstitutional act…we mean , I believe, this : That the act is inconsistent with some give principle or maxim; that het given supreme government has expressly adopted the principle, or , at least, has habitually observed it: that the bulk of the given society, or the bulk of its influential members, regard the principle with approbation : and that , since the bulk of the society regard it with approbation, the act in question must thwart the expectations of the latter and must shock their opinions and sentiments…The epithet unconstitutional as applied to conduct ofa sovereign , and as used with the meaning which is more special and definite , PAA JOY imports that the conduct in question conflicts with constitutional law.’ Thus , the sovereign is not limited by positive law but can be limited by positive morality. Where positive morality is his command. Because, of this , Austin says that het sovereign cannot place legal limitations on himself or his successors (Here he is trying to contemplate the UK parliamentary system). Having described the characteristics of sovereignty Austin seeks the locus of sovereignty within the British constitution. After analyzing the powers of the Crown, the peers, the Commons, ad the electorate he concludes, ‘Adopting the language of most of the writers who have treated of the British Constitution, I commonly suppose that the king and the lords, with the members of the commons’ house, form a tripartite body which is sovereign or supreme. But, speaking accurately, the members of the commons’ house are merely trustees for the body by which they are elected and appointed: and, consequently, the sovereignty always resides in the king and the peers, with the electoral body of the commons.’ Thus for Austin, the sovereign is indivisible. the notional head of the sovereign is one and cannot be divided. COMMAND: A command according to Austin is an imperative form of a statement of the sovereign’s wishes, and it is different from an order in that it is general in its application. It is also different from other expressions of will in that it caries with it the threat of a sanction which may be imposed in the event of the subject of the command not complying with it. For Austin, command involves three things It is the wish or desire conceived by a rational being directed at another rational being to do or to forbear. Evil : Thus, a statement, wish or desire without evil will not amount to a command but a request. There must be an intimation of the wish by words or other signs. Austin says in addition that commands are of two kinds. General or particular. Where a command ‘obliges generally to acts or forbearances of a class, a command is a law…, but where it obliges to a specific act or forbearance, …a command is occasional or particular…’. SANCTION: A sanction is some harm, pain or evil which is attached to a command issued by a sovereign an which is intended as a motivation for the subjects of the sovereign to comply with his or her commands. The sanction is a necessary element of a command and there must be a realistic possibility that it will be imposed in the event of a breach. It is sufficient that there be the threat of the possibility of a minimum harm, pain or evil. Apart from the sovereign, commands and sanctions, Austin says there are three rules which are sometimes termed as laws but which are not imperative in nature : Declaratory laws : These laws do not have an obligation but merely clarify the legal position. They declare rights and privileges. (see Article 2) Laws to repeal laws : In the event of trying to change an existing law, these laws give the processes to be followed. Failure to repeal won’t result in any sanction. Laws of imperfect obligation without attaching sanction: The obligation does not go with sanction. So here you have an obligation to do but you will not be sanctioned if you don’t do According to Austin, these three are not necessarily laws. PAA JOY BENTHAM & AUSTIN COMBINED According to Austin, law is a command given by a determinate common superior to whom the bulk of a society is in the habit of obedience and who is not in the habit of obedience to a determinate human superior, enforced by a sanction. It is the element of command that is crucial to Austin’s thinking, and the concept of law expressed by Austin is sometimes described as the ‘command theory’ (or the ‘imperative theory’) of law. Austin was not the first to expound the command theory of law. In many of his ideas, Austin followed those of Jeremy Bentham who is generally credited with being the founder of the systematic imperative approach to law, although most of what he wrote in this regard was not in fact published until almost a century after his death. For example , in A Fragment on Government, written in 1776 Bentham had said, ‘When a number of persons (whom we may style subjects) are supposed to be in the habit of paying obedience to a person, or an assemblage of persons, of a known and certain description (whom we may call governor or governors) such persons altogether (subjects and governors) are said to be in a state of political society…’ And in Of Laws in General he said , ‘A law may be defined as an assemblage of signs declarative of a volition conceived or adopted by the sovereign in a state , concerning the conduct to be observed in a certain case by a certain person or class of persons , who in the case in question are or are supposed to be subject to his power: such volition trusting for its accomplishment to the expectation of certain events which it is intended such declaration should upon occasion be a means of bringing to pass, and the prospect of which it is intended should act as a motive upon those whose conduct is in question.’ Bentham’s thinking is in respects more penetrating than that of Austin. 3 Austin placed constitutional law under the heading of ‘law strictly so called’. Bentham, recognizing that such should be considered part of the general body of the law, seeks to reconcile the existence of a sovereign, who is subject to no law, with law to which the sovereign is subject. He says ‘There yet remain a class of laws which stand upon a very different footing from any of those that have hitherto been speaking have for their passible subjects, not the sovereign himself, but those who are considered as being in subjection to his power. But there are laws to which no other person in quality of passible subjects can be assigned than the sovereign himself. The business of ordinary sort of is to prescribe to the people what they shall do: the business of this transcendent class of laws is to prescribe to the sovereign what he shall do: what mandates he may or may not address to them; and in general how he shall or may conduct himself towards them …It appears then that there are two distinct sorts of laws, very different from each other in their nature and effect: both originating indeed from the sovereign, (from whom mediately or immediately all ordinances in order to be legal must issue) but addressed to parties of different descriptions: the one addressed to the sovereign, imposing an obligation on the sovereign : the other addressed to the people , imposing an obligation on the people …Here it may naturally enough be asked what sense there is in man’s addressing a law to himself, and how it is a man can impose an obligation upon himself. …But take into account an exterior force, and by the help of such a force it is as easy for a severing to bind himself as to bind another.’ As to the nature of the exterior force, Bentham suggested 3 J G Riddal ‘Jurisprudence’ PAA JOY that this might take the form of a ‘religious sanction’, or a ‘moral sanction’ exerted by the subjects of the state in question, or by foreign states. The imperative theory of law, together with the notion of sovereignty and the illimitable nature of a sovereign’s power can thus be traced back into the writings of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. But while Austin was not the first to put forward all the elements which made up his concept of law, and while Bentham’s thinking on the imperative theory of law was in many respects more penetrating than that of Austin, it is nevertheless Austin who is generally credited with the first full formulation of the theory : it was Austin who both drew the elements together and presented them as a coherent whole , and who gave the theory a central place in the conception of law. CRITICISIMS TO AUSTIN’S COMMAND THEORY OF LAW Austin’s views met with criticism, at least from two fronts, namely the deficiency of the command theory and the separation of morals from law. 4 HART’S CRITICISMS TO THE COMMAND THEORY OF LAW Even among positivists, Austin encountered resistance principally from HLA Hart. Hart’s criticisms fall under three main heads : firstly , that laws as we know them are not like orders backed by threats. The notion of the habit of obedience is deficient Austin’s notion of sovereignty is deficient. Each of these will be taken seriatim. Laws as we know them are not like orders backed by threats. The content of law is not like a series of orders backed by a threat. Some laws, Hart concedes, do resemble orders backed by threats, for example criminal laws. But there are many types of law that do not resemble orders backed by threats, for example laws that prescribe the way in which valid contracts, wills or marriages are made do not compel people to behave in a certain way (as do laws that , for example , require the wearing of seat belts in a car). The function of such laws is different. They ‘provide individuals with facilities for realizing their wishes by conferring legal powers upon them to create conditions, structures of rights and duties…’ Again, laws of a public nature in the field of procedure , jurisdiction and the judicial process , are not comparable with orders backed by threats. Such laws are better regarded as power –conferring rules. Hart contends therefore that orders backed by threats such as the criminal law is distinct from power conferring rules such as the law of contract and that Austin fails to draw such distinction. “But there are important classes of laws where this analogy with orders backed by threats altogether fails, since they perform a quite different social function. Legal rules defining the ways in which valid contracts or wills or marriages are made do not require persons to act in certain ways whether they wish to or not. Such laws do not impose duties or obligations. Instead, they provide individuals with facilities for realizing their wishes, by conferring legal powers upon them to create , by certain specified procedures and subject to certain conditions, structure of rights and duties within the coercive framework of the law. The power thus conferred on individuals to mold their legal 4 Atupare… PAA JOY relations with others by contracts, wills, marriages, & co, is one of the great contributions of law to social life; and it is a feature of law obscured by representing all law as a matter of orders backed by threats…Just as there could be no crimes or offences and no murders or theft if there were not criminal laws of the mandatory kind, which do resemble orders backed by threats , so there could be no buying selling, gifts, wills , or marriages, if there were no; for these latter things, like the orders of courts and the enactments of law-making bodies, just consist in the valid exercise of legal powers.” If someone is going to contend that all laws are like orders backed by threats then they have got, Hart says , to argue that nullity (eg nullity resulting from failure to comply with the Wills Act) is a sanction. Hart confutes the notion. Nullity may well not be an ‘evil’ to the person who has failed to comply with some requirement (for example , as where a child who finds that a contract he has purported to enter into is not enforceable against him). And where a measure fails to become law because it is not passed by the requisite majority, this failure cannot meaningfully be thought of as a sanction. “The provision for nullity is part of this type of rule itself in a way which punishment attached to a rule imposing duties is not. If failure to get the ball between the post did not mean the ‘nullity’ of not scoring, the scoring rules could not be said to exist”. The range of application of law is not the same as the range of application of an order backed by a threat. In Austin’s scheme the law-maker is not himself bound by the command he gives: the order is directed to others not to himself. It is true, Hart concedes, that in some systems of government this is what may occur. But in many systems of law legislation has a force that is binding on the body that makes it. So as a law-maker can be bound by his own law, the Austinian concept of sovereign – command-obedience – sanction cannot be of universal application and so fails. A supporter of Austin may attempt to overcome this objection by seeking to distinguish between the law-maker in his official capacity and the law – maker in his private capacity: in the first capacity hemakes laws; in the second he , long with all the other citizens, is bound by them. hart dismisses this view of the law-making process as failing to represent what actually occurs. What the legislature does, he says, is to exercise powers conferred by rules, within the ambit of which he himself may often fall. The mode of origin of law is different form the mode of origin of an order backed by a threat. An order backed by a threat originates from a deliberate act performed at a specific time. But not all laws can be said to have their origin in a deliberate datable act. For example those customs that are recognized as law within a particular society do not stem from any deliberate datable act. Hart recognizes the existence of an argument in support of the contention that custom does so originate; namely that a custom becomes law when it is recognized as representing the law and is enforced by a court: the sovereign , through the court, orders that the custom should have the force of law. Hart deals with this point saying that customs do not necessarily attain legal status only by application by a court. Just as a statute has legal force before it is (and irrespective of whether it ever is) applied by a court, so a custom can be accepted as having legal force before it is applied by a court. Thus a custom with legal force does not necessarily originate from a datable act. Dealing further with the question of how custom attains legal status, Hart acknowledges that those who support the command theory of law could argue that custom acquires legal force as a result of a tacit order by the sovereign to his judges that a certain custom should henceforth be treated as law, and to his subjects to obey a judge’s decision reached on the basis of a pre-existing custom. he illustrates the matter thus. ‘A sergeant who himself regularly obeys his superiors , orders his men to do certain fatigues PAA JOY and punishes them when they disobey. The general, learning of this, allows things to go on , though if he had ordered the sergeant to stop the fatigues he would have been obeyed. In these circumstances the general may be considered tacitly to have expressed his will that the men should do the fatigues. His non-interference , when he could have interfered, is a silent substitute for the words he might have used in ordering the fatigues.’ So equally , when a sovereign learns that a custom is being enforced as law and does not intervene, then at that moment he tacitly orders that the custom should have the force of law. So the custom becomes law by a deliberate datable act-the decision not to interfere. So if this is accepted –the way in which custom becomes law can be accommodated within the command theory. hart will have none of this. The fault in the argument, he explains , lies in the fact that in any modern state it is in practice rarely possible to say at what point in time a sovereign, whether a supreme legislature or the electorate learns of the application of a custom as law and decides not to interfere. So the tacit approval theory fails. Thus, since custom cannot be shown to become law by a deliberate datable act, the command theory , for this reason as well as those set out earlier , falls down. Checks : Austin limited only on legal Sanctions. But as Bentham suggests, there could be religious sanctions as well. The notion of the habit of obedience is deficient : To explain the ways in which he finds the notion of the habit of obedience to be deficient hart tells a story. Suppose, he says, there is a country in which an absolute monarch has ruled for a long time. The population ahs generally obeyed the orders of the king, Rex, and are likely to continue to do so. Rex dies leaving a son, Rex II. There is no knowing on Rex II’s accession, whether the people will obey the orders he begins to give when he succeeds to the throne. Only after we find that Rex II’s orders have been obeyed for some time can we say that the people are in a habit of obedience to him. During the intervening time, since there is no sovereign to whom the bulk of society are in the habit of obedience, there can, according to Austin’s definition, be no law. Only when we can see that the habit of obedience has become established can we say that an order by Rex II is a law. Yet, in practice, if Rex Ii was Rex I’s legal successor we would regard Rex II’s orders as laws from the start. So the notion of the habit of obedience fails to account for what our experience tells us in fact happens: it fails to account for the continuity to be seen in every normal legal system, when one ruler succeeds another. What is in fact found in any legal system is the existence of rules which secure the uninterrupted transition of power from one law-maker to the next. These rules ‘regulate the succession in advance, naming or specifying in general terms the qualifications of and mode of determining the lawgiver. In a modern democracy the qualifications are highly complex and relate to the composition of a legislature with a frequently changing membership , but the essence of the rules required for continuity can be seen in the simpler forms appropriate to our imaginary monarchy. If the rules provides for the succession of the eldest son, then Rex II has a title to succeed his father. He will have the right to make law on his father’s death, and when his first orders are issued we may have good reason for saying that they are already law, before any relationship of habitual obedience between him personally and his subjects has had time to establish itself. Indeed such a relationship may never be established . Yet his word may be law; for Rex II may himself die immediately after issuing his first orders; he will not have lived to receive obedience, yet he may have had the right to make law and his orders may be law. ‘ In explaining the continuity of law-making power through a changing succession of individual legislators, it is natural to use the expressions “rule of succession”, “title”, “right to succeed’, and “right to make law”. It is plain, however, that with these expressions we have introduced a new set of PAA JOY elements , of which no account can be given in terms of habits of obedience to general orders.’ So in this further respect the command theory is proved to be inadequate. Not only does the habit of obedience fail to account for the continuity of law when Rex II succeeds Rex I, it fails to account for the persistence of the legal force of Rex I’s orders after his death. Yet, unless and until Rex II countermands an order by Rex I, the orders of Rex I will ,we know from what happens , continue to be regarded as law. If it is contended that the persistence of the legal force of Rex I’s orders is to be accounted for by Rex II having , on his accession, tacitly ordered that Rex I’s orders should continue to be law, then the same objections to this notion can be made here as were made when the notion was sought to be used earlier to deal with the question as to how customs acquire legal force. The answer to the problem of why Rex I’s orders are still law after his death is , Hart says, in principle the same as the answer to eth earlier problem, Whey are Rex Ii’s orders law before the populace have acquired the habit of obedience? The answer to both problems ‘involves the substitution , for the too simple notion of habits of obedience to a sovereign person of the notion of currently accepted fundamental rules specifying a class or line of persons whose word is to constitute a standard of behavior for the society, ie who have the right to legislate. Such a rule , though it must exist now, may in a sense be timeless in its reference: it may not only look forward and refer to the legislative operation of a future legislator but it may also look back and refer to the operations of a past one.’ Atupare brings out the deficiency in the notion that the sovereign is habitually obeyed in the Austinian sense as follows “For instance, locating of the Austinian sovereignty in modern, young constitutional democracies like Ghana and Nigeria may be difficult. The people in these states retain the power, in the Lockean sense, to change the Constitution through amendment, when the legislative authority is so wicked to design laws against their general interest. in that case, the assertion that people habitually obey a legally unlimited sovereign looks feeble. Sovereignty in this case is exercised by the people [Article 1 of the 1992 Constitution] and obedience in its non-habitual form is rendered to be the people themselves. Besides, transitional regimes or regimes set up through coups d’etat in Africa and elsewhere would have difficulty with this conception. In such states, new leaders are far from being habitually obeyed by their citizens.”5 So here again the command theory fails to explain what we know happens in any actual legal system. Austin’s notion of sovereignty is deficient: In Austin’s theory of law , while there may be political limits on a sovereign’s power (eg regard for popular opinion), there can be no legal limits on a sovereign’s powers, since, if he is sovereign, he does not obey any other legislator. Thus, according to Austin, if law exists within a state , there must exist a sovereign with unlimited power. But when we examine sates in which no one would deny that law exists we find supreme legislatures the powers of which are far from unlimited. For example, the competence of a legislature may be limited by a written constitution under which certain matters are excluded from the scope of its competence to legislate upon. Yet no one would suggest that a legislative act by such a legislature did not create valid law. We cannot say that such restrictions are merely conventions or have merely moral force. If the restrictions are overstepped the law purported to have been made will be declared invalid by the courts. So the restrictions have legal force. Thus ‘…the conception of the legally unlimited sovereign misrepresents the character of law 5 Atupare … PAA JOY in many modern states’.6To understand the true nature of a legal system and how law comes into existence we need to think in terms , not of a sovereign with unlimited powers, but in terms of rules , rules that confer authority on a legislature to legislate, rules used by the courts ‘as a criterion of the validity of purported legislative enactments coming before them’:7 to show that a law is valid’…we have to show that it was made by a legislator who was qualified to legislate under an existing rule’.8 If in the face of this argument, someone still clings to Austin’s view of law as the command of a sovereign it is necessary for them to show that even if , as they may concede, the powers of the supreme legislator may be limited , a sovereign does nevertheless exist, a sovereign ‘behind the legislature’, a sovereign who (or which) makes the rules which determine the legislature’s competence. If such a sovereign can be found one hole in the bottom of Austin’s bucket is plugged. Those who seek such a sovereign may contend that ultimate sovereignty rests with the electorate. But if it is in the electorate that sovereignty rests then when we apply this idea to Austin’s concept of law as the commands of a sovereign to whom the bulk of the populace is in the habit of obedience, we find ourselves saying that the populace (or that part that constitutes the electorate) is in the habit of obedience to itself. ‘Thus the original clear image of a society divided into two segments : the sovereign free form legal limitation who gives orders , and the subjects who habitually obey, has given place to the blurred image of a society in which the majority obeyorders given by the majority or by all. Surely we have here neither “orders” in the original sense (expression of intention that others shall behave in certain ways) or “obedience”. In order to meet this criticism, Hart explains , ‘a distinction may be made between the members of the society in their private capacity as individuals and the same persons in their official capacity as electors or legislators. Such a distinction is intelligible; indeed many legal and political phenomena are most naturally presented in such terms; but it cannot rescue the theory of sovereignty even if we are prepared to take the further step of saying that the individuals in their official capacity constitute another person who is habitually obeyed. For if we ask what is meant by saying of a group of persons that in electing a representative or in issuing an order, they have acted not “as individuals” but “in their official capacity”, the answer can only be given in terms of their qualifications under certain rules and their compliance with other rules , which define what is to be done by them to make a valid election or a law. It is only by reference to such rules that we can identify something as an election or a law made by this body of persons.’ And since such rules define ‘what the members of the society must do to function and an electorate (and so for the purposes of the theory as a sovereign) they cannot themselves have the status of orders issued by the sovereign, for nothing can count as orders issued by the sovereign unless the rules already exist and have been followed.’ These arguments against the notion of a sovereign with legally unlimited powers , Hart concludes , like those put forward earlier ‘are fundamental in the sense that they amount to the contention that the theory is not merely mistaken in detail, but that the simple idea of orders, habits, and obedience , cannot be adequate for the analysis of law. What is required instead is the notion ofa rule conferring powers, which may be limited or unlimited , on persons qualified in certain ways to legislate by complying with a certain procedure.’ 6 H L A Hart The Concept of Law p 67 Ibid, p 68 8 Ibid, p 69 7 PAA JOY JG Riddall in ‘Jurisprudence’ suggests that both Hart’s theory of law and that of Austin in one respect share common ground, that of their approach to jurisprudence. Both set out to determine the nature of law by the process of analysis: they are both members of the analytical school of jurists, jurists who seek to strip the flesh from the skeleton to find the structure beneath. It is from Austin’s conclusions that Hart dissents , not from his method and approach OTHER CRITICISMS ‘ On a different ground, Salmond protests that the Austinian conception of law does not treat seriously the issue of legal rights, as it fails to provide for a place within the entire analysis of an ethical basis for rights. It “attempted to deprive the idea of law of that ethical significance which is one of its most essential elements”. Salmond’s rejection of the command theory based on ethical considerations in respect of rights resonates well with a functional conception of public law that protects the rights and wellbeing of the citizenry. It also speaks to a constitutionally limited government where law is not the exclusive command of the legislator, but an expression of a composite of well-considered values of the people from whom the power of the legislator is derived.’9 sovdeclaratory laws , power conferring laws, and duty imposing laws Look at the issue with sovereignty-in constitutional democracite,s the soveirgn is the people and not parliament and it is difficult to oitn to a particular one person-look at our 1992 constitution RULE OF RECOGNITION According to Hart, wherever there is a rule of recognition, people have a way of finding out what the primary rules are.10 In modern societies there may be various sources of law. These may include, for example a written constitution, legislation , and judge’s decisions. These may e placed in an order of superiority; for example, legislation may be able to override judges’ decisions. In the British system, judicial precedent is subject to legislation. Judicial precedent is , however, a separate soruce of law: it does not derive its authority as a source of law from legislation. Thus precedent is subordinate to legislation but independent of it as a source of law. Hart thus proposed a “rule of recognition”, a test accepted by officials for determining what normative standards form part of the legal corpus or what factual propositions should be accepted as valid law in a community. The significance of the rule of recognition is to make law-making subject to to the idea that “nothing which the legislators do makes law unless they comply with fundamentally accepted rules specifying the essential law-making procedures”.11 Certainly , the sovereign lawmaker must be subject to the secondary rules, including , most importantly, the rule of recognition; it cannot succeed in making ‘law’ unless its ‘law’ complies with the master rule that defines what ‘law’ is. In any society, is there one rule of recognition, or may there be more than one ? From one point of view there may be several –the constitution, legislation and judicial decisions, each of these can provide 9 Atupare… Hart says legal rules are of two kinds, ‘primary’ rules and ‘secondary’ rules. Primary rules are ones which tell people to do things, or not to do things. The lay down duties. These primary rules are to do with physical matters. Secondary rules are ones which let people , by doing certain things, introduce new rules of the first kind, or alter them. They give people (private individuals or public bodies) power to introduce or vary the first kind of rule. 11 Atupare : constitutional justice in Africa 10 PAA JOY authority for establishing the validity of a law. From another point of view, the better view , there can be only one rule of recognition in any one legal system, that which establishes the supreme source of authority for legal validity, rule that may have subsidiary rules but which laws down the order of priority between them. A rule of recognition ( that is one enabling people to know what is and what is not law) is seldom in practice expressed as an actual law, though occasionally the courts may make some statement about how the rule works, eg when they say that Acts of Parliament override other sources of law. When people say that something or other is the law ‘because parliament has said so’ they show that they accept this as a rue of recognition; they are looking at the rule from an internal point of view. Someone looking at the rules of recognition from an external point of view , someone who is an outsider who does not accept the British rules of recognition, would say ‘In Britain, they accept as law whatever the Queen in Parliament enacts’. When we say that a rule is ‘valid’ within any particular system, we mean that it complies with the rules of recognition of that system. The validity of a rule does not depend on the fact that the rule is obeyed more often than it is not obeyed. There may, however be a rule of recognition that provides that if a rule is not obeyed over a long period, it should cease to be a rule: there maybe some kind of ‘rule of obsolescence’. But nevertheless , the validity of a rule, and the question of whether it is obeyed, are two separate matters. The fact that there are various rules of recognition, with one of them supreme –a hierarchy of rules of recognition, with one of them at the top-should not be thought of as meaning that in any legal system there is one supreme, sovereign, legislative power which is legally unlimited. Just because a particular rule of recognition is supreme, this does not mean that any legislative body necessarily has unlimited power. For example , in the United States there are rules of recognition but there is no legislator with unlimited powers. Now , to introduce a further idea, hart asks us to suppose that someone questions whether a purported bye-law of the Oxfordshire County council is valid. It is found that it is valid because it was made in exercise of powers conferred by a statutory order made by the Minister of Health (So the bye-law satisfies this ‘rule of recognition’.) The validity of the statutory order made by the Minister is questioned. It is found that it valid because it was made according to the provision of a statute empowering the Minister to make such an order. Next, the validity of the statute is questioned. We find that the statute is valid because it was passed by Parliament and signed by the Queen. At this point we have to stop, since, according to our notions in this country, what the Queen in Parliament enacts is law. the rule that what the Queen in Parliament enacts is law is a rule of recognition. In this , it is like the other rules of recognition mentioned supra . But it is unlike the others in that there is no rule of recognition to test the validity of this rule : there is no rule of recognition to test the validity of the rule that what the Queen in Parliament enacts is law. So this rule of recognition is the ultimate rule of recognition. A statement that a statue is valid because it complies with the rule that what the Queen in Parliament enacts is law, is made from an internal point of view. It is internal because it looks at the matter from the viewpoint of people inside the legal system: they accept that what the Queen in Parliament enacts is law. If we say that in England the rule that what the Queen in Parliament enacts is law is used by the PAA JOY courts and citizens as the ultimate rule of recognition , we are making the statement from an external point of view. We usually only talk of a rule being valid within a legal system. We say that the law is valid because it complies with the rule of recognition of that system. But Hart explains , no question can arise as to the validity of the rule of recognition itself; it can neither be valid nor invalid-it is simply accepted within the system as being approprpate fro deciding what is an what is not a valid rule. In a legal system which had only primary rules, because of the absence of any rule of recognition (a secondary rule) any statement that a certain rule existed cold only be made as a statement of fact, such as might be made (and verified by observation) by an outside observer. On the other hand, where there is a mature system of law, with primary and secondary rules, including a rule of recognition then a statement that a rule ‘exists’ can be made, not only from an external point of view, as a statement of fact, but also from an internal point of viw. In the latter case, the statement that the rule ‘exists’ carries with it the implication that the rule complies with the system’s rule of recognition and is thus valid according to the system’s test of validity. A rule of recognition does not fit into any of the conventional categories used in classifying laws in a legal system. For example, a rule of recognition does not fit in to either of Dicey’s two categories of constitutional arrangements-laws strictly so called (eg statutes etc) and conventions (eg that the Queen does not refuse to assent to a bill passed by Parliament). Distinct from the problem of how to classify a rule of recognition, there is the problem of knowing how to show that a rule of recognition, which underlies the constitution and the whole legal system, and which surely must be law, is law. Some people would answer thisquestion by saying that at the base of any legal system there is something which is ‘not law’, which is ‘pre-legal’ or ‘meta-legal’. Others would say that this something which underlies the legal system is merely ‘political fact’. The truth is that the rule of recognition is both law and fact : we cannot convey the idea of a rule of recognition adequately if we think we must label it either ‘law’ or ‘fact’. The best way of understanding the nature of a rule of recognition is to regard it as being capable of being looked at from two points of view-from an external point of view (that of an outside observer who notes that, as a matter of fact, the rule exists in the actual practice of the system) and from an internal point of view ( that of someone inside the system who accepts the rule as the correct one for determining what is the law). “The statement that now a rule exists may now no longer be what it was in the simple case of customary rules-an external statement of the fact that a certain mode of behavior was generally accepted as a standard in practice. It may now be an internal statement applying an accepted but unstated rule of recognition and meaning (roughly) no more than ‘valid given the system’s criteria of validity’. In this respect, however, as in others a rule of recognition is unlike other rules of the system. The assertion that it exists can only be an external statement of fact. For whereas a subordinate rule of a system may be valid and in that sense ‘exist’ even if it is generally disregarded , the rule of recognition exists only as a complex, but normally concordant, practice of the courts, officials, and private persons in identifying the law by reference to certain criteria. Its existence is a matter of fact.”12 checks: rules of change; rules of recognition and rules of adjudication 12 H L A Hart The Concept of Law p 110 PAA JOY HANS KELSON-PURE THEORY OF LAW Hans Kelsen began thinking about the nature of law during the course of examining the Austrian Constitution before eth First World War. Troubled during the first war , he assisted in the drafting of Austrian First constitution ( 1920 Constitution) . The first full formulation of his theory appeared in 1918. the first presentation of his theory in English was in 1934 after Kelsen had gone to the United States. In 1945, he published General Theory of Law and Stateand after various articles, a second , revised, edition in 1967. A complete presentation of the theory was made in 1964. Kelsen called his theory (which he modified over the course of his life) the ‘pure theory of law’, his object being to identify the very essence of law, the one thing that makes something law, as opposed to the other forms of direction that can exist in any society. (Kelsen was not the first to seek such a theory. Grotius, in 1625 in the Prolegomena to De lure Belli ac Pacishad written : ‘With all truthfulness I aver, just as mathematicians treat their figures as abstracted from bides, so in treating law I have withdrawn my mind from every particular fact). Kelsen has often been described a positivist but Kelsen’s normativism is conceptually distinct from the empirical tradition of legal positivism, upheld in the post-war period by Hart. Kelsen rejects legal positivism because it confuses the law with fact. For Kelsen the law consists of norms . the relationship between norms is one of “imputation”, not causality. natural science is concerned with causal explanations of the physical world, whereas normative science , such as law or ethics is concerned with conduct as it ought to take place determined by norms. The separation of laws from morals by Kelsen is seen in two main ways : the first is his underscore for positivism leanings The next explain his theory that law must be pure and that it must stay uncontaminated by other values. One of those values being morality. Other values include regulation , ethics etc. It has been argued that these other factors (religion, ethics, politics) which have adulterated law hence making it impure may suggest that Kelson’s notion of law is not in line with the general notions that positivists share. Thus for positivists, law and morality are not fused. It should be noted that keelson does not distance himself from this new thing, he only includes other factors like ethnic and religion. One may argue that religion, and ethnicity all come within the purview of morality. However, to Kelson, these are distinct. So Kelsen admits the study of law has been “adulterated” by other disciplines. These disciplines deal with subject matters “closely connected with law. But the pure theory of law, Kelsen insists, “undertakes to delimit the cognition of law against these disciplines…because it wishes to avoid the uncritical mixture of methodologically different disciplines …which obscures the essence of law”. 13 NORMS 13 Lloyd : quoted from The pure theory of law, p.1 PAA JOY Kelson writing in German , used the German word norm. The principal meaning of norm in German is ‘standard’. Thus , it is the standard to which human conduct are supposed to be measured. According to keelson, for an act to be deemed a legal, such act must conform to a legal norm. What makes the jailer’s turning the key a legal act, is the existence of the norm that ends with , ‘…then the jailer ought to turn the key’. kelsen uses as an example an order by one person to hand over money to another . The order may be by a gansgster or by a tax official. Both have wheat Kelsen calls the same ‘subjective meaning’ (ie as to what actually happens, an order is made to hand over money). But if the tax official’s order is made in accordance with a valid norm, then the order has what Kelsen calls an ‘objective’ meaning (ie a legal significance). So it is the existence of the legal norm that distinguishes the order of the official from that of the gangster. According to Kelsen, the validity of every norm depends on the validity of another norm, the whole series forming , as it were an ascending hierarchy. THE GRUNDNORM If a norm can be derived from another norm, does this mean one can continue this derivation ad infinitum? Theoretically , yes, but, in practice, since norms are concerned with human conduct, there must be some ultimate norm postulated on which all the others rest. This is the Grundnorm (basic norm). In any legal system it is only by presuming the validity of the original , basic norm (which Kelsen calls the ‘grundnorm’),that the norms that descend from it can be counted as valid. ( in this aspect of this theory Kelsen showed the influence of Kant, for whom in any branch of knowledge, some things must be presupposed. Kant believed that it was a task of the philosopher to search of the universal elements of knowledge that have to be presupposed the order that sense can be made of all the rest). According to Harris ‘When and Why does the Grundnorm Change?’ ‘The Grundnorm is the hypothesis which closes up the arch of legal logic’- the Grundnorm is the keystone at the top that locks , and holds, the arch in place. Remove this and the whole edifice of legal validity collapses. Simply put, the Grundnorm is the ‘master norm’. When the norms are arranged in the form of a pyramid, the Grundnorm occupies the apex. So in our Ghanaian Jurisprudence,the Grundnorm may be stated to be the 1992 Constitution. This may be so by the combined effects of Article 1(2) and Article 11 of the constitution. Under Article 1(2) , the Constitution has been stated to be the supreme law and any other law found to be inconsistent with any provision of the Constitution shall ,to the extent of the inconsistency be void. By analogy, the Constitution of Ghana becomes the Grundnorm and for any other norm, (other laws of Ghana ) to be valid, it must be consistent with the Constitution which is the Grundnorm. These other norms can be gleaned from Article 11 which gives a list of the laws of Ghana – the constitution, enactments made by or under the authority of the Parliament established by the constitution; any Orders, Rules and Regulations made by any person or authority under a power conferred by the Constitution; existing law and the common law. The process by which each of these norm gets more and more specific keelson terms as concretization. Thus, the higher norms will be concerned with how law, eg. Statute law, is created; then at the next tier with the administration of justice; and finally with a norm that decrees certain action in a specific case PAA JOY The validity of the Grundnorm is assumed . But why ? Or rather, how do we tell whether in any legal system the validity of the Grundnorm is to be assumed ? Kelsen’s answer is that we look to see what happens. If the judge does , as the norm requires, pass sentence and the jailer does , as the norm requires, turn the key –if the norms of the system are observed, then we have no option but to accept that the validity of the Grundnorm is presupposed Thus we assume the validity of the Grundnorm if the norms that descend from it are observed if the ‘oughts’’ are implemented. So we can say that with regard to the individual norms of a system, validity depends on another ‘higher’ norm. With regard to the grundnorm, validity depends on efficacy. With this in mind we are in a position to understand what Kelsen means when he defines law as ‘A system of coercion imposing norms which are laid down by human acts in accordance with a constitution the validity of which is pre-supposed if it is on the whole efficacious.’ So, in establishing whether the grundnorm is valid we look to the implementation of the individual norms, ie we look to see whether the directions to officials are carried out. The question which arises then is If the test of the validity of the Grundnorm is efficacy, what is the test of efficacy ? When can we say that efficacy exists? Efficacy is to be judged , Kelsen says, by two criteria. The first test is to see whether the rules that can be deduced from legal norms are obeyed, for example whether the rule ‘Do not drive over 70 mph’ (the rule deduced from the norm ‘If X drives over 70 mph, then Y ( a policeman) ought to…’) is obeyed. Secondly, if the rule is not obeyed , whether the primary norm , that directed to officials to take specified action , is complied with. the addition of this second test , and for Kelsen this is the test that has primacy , throws new light on the notion of efficacy. (Austin’s ‘habit of obedience’ took account only of the first test). SANCTIONS For Kelsen , every system of norms rests on some type of sanction, though this may be of an undifferentiated kind, such as disapproval by a group. The essence of law is an organization of force, and law thus rests on a coercive order designed to bring about certain social conduct. Sanctions are the key characteristic of law not because of any supposed psychological effectiveness but because it stipulates that coercion ought to be applied by officials wheredeficits are committed. The law attaches certain conditions to the use of force, and those who apply it act as organs of the community. Kelsen basis this view on the historical facts (as he asserts) that there has never been a “large” community which was not based on a coercive order. Kelsen commits himself to the view that every norm to be “legal” must have a sanction, though this may be found, as for instance in constitutional law, by taking it together withother norms with which it is interconnected. Kelsen treats any breach of a legal norm as a ‘delicit,” whether this would normally be described in traditional terms as falling within the criminal or the civil law. For Kelsen, to be legally obligated to to a certain behavior means that the contrary behavior is a delict and as such is the condition of a sanction stipulated by a legal norm. Since Kelsen regards as a sanction as an essential characteristic of law, no conduct can amount to a delict unless a sanction is provided for it. This view has been criticized , with some warrant , on the ground that though the absence of of a sanction may make law ineffective, this is not the same as its being invalid, nor does the absence of a sanction necessarily entail invalidity. Emphasis on sanctions also underplays the PAA JOY significance of duties. There aer many examples of public authorities which have obligations imposed on them but where no sanctions as such follow from default. 14 A further feature of Kelsen’s analysis of the sanctionist view of law is that legal norms are stated in the form that , if a person does not comply with a certain prohibition, then the consequences is that the courts ought ot inflict a penalty , whether criminal or civil. It follwos that for Kelsen the content of legal norms is not primarily to impose duties on the subject to conform, but rather to lay down what judges or officials are expected to do in the event of a delict. Accordingly, for Kelsen the norm which lays down the sanction , involving a direction to the judge , is the primary norm, though he recognized that there is a secondary norm which stipulates the behavior which the legal order endeavors to bring about by announcing the sanction. This conflicts with the orthodox view that duties set standards of conduct and accordingly impose obligations on society as a whole. Revolutions What happens to the law in the event of a revolution? Kelsen says that after a successful revolution the Grundnorm changes. Once an existing regime , A, has been replaced by a new one, B, and the laws of regime B are observed then the Grundnormof the new regime becomes , ‘The constitution established by regime B, and the laws made under it, ought to be observed.’ It is only on this assumption that the validity of the laws of the new regime can rest. No one would maintain that ‘after a successful revolution the old constitution and the laws based thereupon remain in force, on the ground that they have not been nullified in a manner anticipated by the old order itself’. 15 A shrewed test for assessing whether the grundnorm has changed ahs been suggested by Harris –it has changed when a person who proposed to write a law textbook presenting the law of the former regime would be considered as fulfilling no juristically useful purpose. In dealing with revolutions we have spoken of a change in the Grundnorm , the key stone in the arch of logic of legal validity. But because the keystone is changed, this does not mean that all the previous Grundnorm have changed. The laws of the previous regime will only continue if their continuance is sanctioned by the Grundnorm of the new regime. Applying the test of efficacy in revolutions, the old regime will only be displaced if the new revolution is efficacious. Hence failure to succeed in a revolution or coup d’tate, hence not being efficacious will result in treason. THE RULE OF RECOGNITION: A COMPARISON 16 There are superficial similarities between the Grundnorm and Hart’s rule of recognition. The rule provides authoritative criteria for identifying primary (and, presumably, other secondary) rules. How are these rules of recognition to be ascertained? Hart points out that such rules are often not expressly stated, but can be shown by the way in which particular rules are identified by the courts and other 14 Lloyd’s Introduction to Jurisprudence p. 312 General Theory of Law and State p 118 16 See Lloyd 15 PAA JOY officials. Whether a primary rule is “valid” really amounts to saying no more than that it passes all the tests provided by the appropriate rule of recognition. But in what sense can the rules of recognition themselves be regarded as “valid”? hart appears to recognize that such rules may themselves be formed on a hierarchical pattern and that, therefore, the validity of one or more of these rules may depend upon some higher rule of recognition, but this still leaves open the Kelsenite question as to the status of any ultimate rule since the only point is whether it is accepted by those who generate the system. There is, therefore, no assumption of validity, but its acceptance is simply factual. Should we then call the basic norm of the system either law or fact? In a sense , avers hart, it is both. The rule does provide crtierai of validity within the system and , therefore it is worth calling such a rule, law: there is, however, also a case for calling it fact insofar as it depends for its existence upon actual acceptance. This fact of acceptance may be looked upon from two points of view, namely, form the point of view of the external statement of fact that the rule exists in the actual practice of the system, and also from the internal statements of validity which may be made by those in an official capacity who actually use it to identify law. Hart also points out that although the notions of validity and efficacy may be closely related in a legal system, they are by no means identical. Their close relationship is demonstrated by the fact that if there is so little efficacy in a whole system of law, it would really be pointless to attempt to assess what actual rights and duties might exist there under or the validity of particular rules. As to the question whether every system of law must be referable to some basic norm, Hart rejects Kelsen’s view that this is an essential presupposition of all legal systems. All that it means , where a system lacks a basic norm, is that there will then be no way of demonstrating the validity of individual rules by reference to some ultimate rule of the system. Hart poinst out that this is not so much a necessity as a luxury found in advanced social system . In simple forms of society we may have to wait and see whether a rule gets accepted as a rule or not. This does not mean that there is some mystery as to why rules in such a society are binding, which a basic rule, if only we could find it, would resolve. The rule in a simple society , like the rule of recognition found in a more advanced system, are binding if they are accepted and function as such. Thus Hart argues, there is no reason why we should insist that international law must have a basic norm. Such an assertion depends upon a false analogy with municipal law. International law, by contrast, may consist of a set of separate primary rules of obligation which are not united in this particular way. Indeed, the insistence upon the need for a basic norm, within the context of such a system as modern international law, often leads to a rather empty repetition of the fact that society does observe certain standards as obligatory . Thus Hart refers to the rather empty rhetorical form of the so-called basic norm of intentional law to the effect that “States should behave as they have customarily behaved”. As for the rule regarding the binding force of treaties , this is merely one of the “set” of rules accepted as binding. Of course, if the rule was generally accepted that treaties might bind not merely the parties thereto but other states, then treaties would have a legislative operation and the established form of treaty –making might have to be recognized as in itself one of the criteria of validity. But international law has not yet reached this stage. REALISM PAA JOY There are two variants of realism: American and Scandinavian. They both are realist in the sense of trying to look at law stripped of mystique and metaphysics, to see how law actually works in a society or in practice. However their answers are different as American realism was a reaction to formalism. Formalism is based on a priori reasoning while American realism is pragmatic. The Scandinavians concentrated on the verification of concepts like ‘right’ and ‘duty’ in a psychological way while the Americans sought to show that legal decisions were not predictable if one merely looked at the logical application of rules. the prohphesies of what the courts will do in fact what he means by the law. They are not concerned with the question , ‘what do the rules of law have to say about this problem?’ but rather , ‘what happens in life –the court rooms , law offices and prosecutors’ conferences?’ In this school of jurisprudential thinking certain names stand out , in particular are those of Oliver Wendell Holmes Jnr (1841-1935), Jerome Frank (1889-1957), John Chipman Gray (1839-1915) and Karl Llewellyn (1893-1962). Oliver Wendell Holmes Jnr an Americana Jurist is the forefront of realism. Realism is useful for judicial definition of law. To them, the judiciary is the best person to define law. It was a remark by Oliver Wendell Holmes that set the ball rolling. ‘Take the fundamental question, What constitutes the law ? You will find some text writers telling you that it is …a system of reason, that it is a deduction from principles of ethics or admitted axioms or what not, which may or may not coincide with the decisions. But if we take the view of our friend the bad man we shall find that he does not care two straws for the axioms or deductions , but that he does want to know what the Massachusetts or English courts are likely to do in fact. I am much of his mind. The prophecies of what the courts will do in fact, and nothing more pretentious , are what I mean by the law.’ For the Realists, all law are judgemade law. Statutes are not laws by virtue of their enactment. They only become law when applied by a decision of the courts. Only then does a legislative enactment spring to life and acquire actual force. Legislation is therefore no more than a source of law: it is the courts that put life into the dead words of the statutes’. 17 So to them, nothing pretentious is what will be considered law than the prophesises of the courts. Because of that common position, they have decided that when a judge is considering legal questions, legal factors don’t matter. The legal factors as have been stated supra include –legislations ( Acts, Constitutions, L.Is, E.Is, C.Is). The reason for the focus on the judiciary is that they are transitory in nature ( in that they are about becoming law) Holmes states that the factors that matter are the morality of the judge, the politics of the judge and the prejudices of the judge. The morality of the Judge : For the realists, you have to investigate the moral background of the judge The politics : Eg. Taking the U.S. instance where the judge may be a democrat or Republican so you should know how to address them Prejudices :Associations, relations with others or groups 17 J C Gray The Nature and Sources of Law (2nd edn) p 125 PAA JOY Disadvantates:The notion that legislation wasn’t important cannot be true. Another has to deal with the separation of powers argument: It is parliament that makes the lawn and not the judges. The judge’s role is to interpret the law (See Montesqui & John Locke) The US is much concerned with the realist concept unlike typical common law judges. Whether the realist concept is applicable in our jurisdiction. American Realism: American realism are concerned to show and justify skepticism about traditional explanations of the judicial process in terms of judges making decisions by following rules laid down by the legal system. In his article, ‘law and morality in the perspective of legal realism’, Harry W Jones describes the activities of American realists as sharing a natural conviction that the processes of law administration involve operations far more complex than the search for and logical application of coreexisting doctrines. John Chipman Gray (1839-1915) Gray’s thinking was influenced by Austin although he rejected Austin’s definition of ‘law’. He believed that eth law is the whole system of rules applied in the courts. The statute exists for the protection and forwarding of human interests, mainly through the medium of rights and duties. However, not every member of the society knows perfectly well about his own rights and duties, else there would be no need for the courts. To determine in actual life the rights and duties of the citizens, the courts look at the facts and also lay down rules according to which they deduce legal consequences from facts. These rules are the law because between the legislative and the judicial organ, the judicial organ has the final say on what the law is. He supports his statement with a quote by bishop Hoadly , ‘whoever hath an absolute authority to interpret any written or spoken laws, it is he who truly , the law – giver to all intents and purposes, and not the persons who first wrote or spoke them…’ in his book, ‘the natural and sources of law’, he argued that the actual effects of law on people depend on the opinions, preconceptions and ideas of particular judges, particularly with respect to how the law is interpreted, for ‘it is the meaning declared by courts and with no other meaning that they are imposed on the community as law’. He continued that the judgment of a corut has the force of law. It has the power of a fixed legal binding order, more direct working , than the statutory , merely abstract statement of the law. The case against Gray is that he denies the facilitative function of certain statutes such as the companies Act. One does not go to court in order to incorporate a company yet the procedure and requirements for doing are prescribed in statute. To Cardozo, a critic of realism , he believes the logical conclusion then is, ‘the law never is, but it is always about to be’. Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr. (1841-1955) He was the associate justice of the Supreme Court of the United States. His book, ‘the common law’ was a classic work of Anglo-American jurisprudence. his essay ‘the path of the law’ is probably the most influential essay in American thought. His position is popularly called the bad man or prediction theory of law. Thus, if one wanted to know what the laws of a society are , one must approach the question from the perspective of the bad man. The bad man does not care about morality, nevertheless, he, just like the good man wishes to avoid an encounter with the law. When he asks his lawyer whether some contemplated action is legal, what he PAA JOY want to know is how pubic power is going to affect him. He does not deny that moral conceptions influence the growth of the law. These are often hidden from sight by the logical form into which the judges opinion is cast. This leaves out the perspective of the judge. This is because the judge when confronted with such an issue does not ask himself what he or other judges will predict. To respond that he predicts what the higher courts will predict does not hold water as he himself can be a member of the highest court. Holmes does not take up the question, ‘where do the courts derive their authority’. What is it that constitutes the judges as jural agents and their decisions as jural acts? An answer to this is the delegation of law of laws of competence. To interpret these as predictions of the judgments of the courts seem to involve circularity. Another problem of the Holme’s theory is that it is court –centered and does not seem to apply to legal systems without courts. This led some realist to broaden the scope to law-enforcing or law-applying officials. But what these officials enforce or apply are laws not predictions about each other’s judgment or behavior. This is to be understood to mean laws are always ready-made and waiting to be enforced or applied . Kantorowitz also believes that a court-centered or even official –centered view also distorts the perspective of the ordinary member of society in relation to laws. For example in a game of football the rules are known and followed by the players. To say that the rules are generalized predictions of what the umpire will say is absurd. Karl Llewellyn (1893-1962) He thought that the ruled were merely , ‘pretty play things’. He proposed two basic function of law. The law aids the survival of the group The law engages in the quest for justice , efficacy and a richer life. To assist the law in fulfilling these functions the institution of law has a number of law-jobs. He list the law –jobs as follows The disposition of trouble case The preventative channeling of conduct and expectations so as to avoid trouble and not only looking at the new legislation but at its purpose The provision of private law activity by individuals and groups, such as the autonomy inherent in a law of contract The net organization of society as a whole so as to provide integration , direction and incentive. Jerome Frank Judge Jerome Frank was a distinguished exponent of realism. He insists that there are really two groups of realists, “rule skeptics”, as he calls them, who regard legal uncertainty as residing principally in the “paper” rules of law and who seek to discover uniformities in actual judicial behavior and “factskeptics”, who think that the unpredictability of court decisions resides primarily in the elusiveness of facts. The former , he suggests, make the mistake of concentrating on appellate courts. PAA JOY Frank believed that the certainty of prediction could only be achieved in the appellate courts. In the lower courts, the uncertainty of the fact-finding process is the reasons why decisions are unpredictable. This unpredictability is a result of the values, etc of the judges together with the uncertainties of juries and witnesses. Much depend on the witness who may be mistaken as to their recollections. Also , judges and juries bring along their own beliefs, prejudices and personal predilections into their decisions about witnesses, parties, etc. these prejudices are difficult to predict. Frank’s view is not without criticism. It is not all the case that all questions of fact are unpredicatable as he describes. Within the bounds of the rules of evidence, a professional adviser can make a fair prediction in most cases what facts the courts will accept as proved and what rules of law are to be applied to them. And what of the cases which go to the judge on a basis of an agreed fact to see what eth legal rule is ? An example of such a case is Donoghue v Stevenson. CRITICISMS A problem is the issue of separation of powers because for the realists, the judges make the laws and not parliament. The legislature is thus rendered redundant. The meaning is that there will be only two arm of government instead of three. Is it true that in determining matters, this is what matters and not positive or posited law? Positive law is inevitable so they cannot say that legal practice is not important Their argument will lead to serious disaffection between the three arms of government Harris, J. W. (1997) Legal Philosophies Lexis Nexis “ Minimally, realists say that ‘rules’ are not all that matter in the administration of justice, and there has probably never been a theorist who denied that. More positively, the movement has had some influence in directing research towards non-rule-governed operations-towards studies of the personal background of judges , the actual workings of the jury system , the practical importance of availability of legal representation, and the consequences of formality in procedure. A realist approach would require us to concentrate , not on the reasons judges give for their decisions, but on what they do. In an extreme form, it would regard all legal reasoning as mere surface talk. I have come across practitioners who in their cups, talk about judges in this way: “ you wouldn’t get very far with that argument before judge X, given the way he feels about deserting husbands, etc.” If it is systematically true that, whenever there is an arguable point, arguments based on the purpose of a rule, or Parliament’s intention , or some legal principle , might as well not have been advanced because the judge’s prejudices alone determine his decision, then perhaps law is, as F. Rodell argues, “a high-class racket”. There remains the difficulty, which many critics of realism have pointed out, that if legal science is to be transformed into a science of prediction, just what are judges supposed to do? Frank ahs said that judges should be as conscientious as possible in introspecting about their motives. At least they should be clear that justice in the case at bar is their goal, not some solution dictated by ‘justice according to law’. If the belief that rules matter, inside and outside courts, were to be totally discredited, it would not merely confirm the cynicism that many share about the law; it would also lead to total pessimism about het utility of law reform. Why bother change the rules? The only possible ‘law reform’ would be to PAA JOY substitute officials with desirable prejudices for those officials we have. Judges, old or new , would automatically have complete discretion, but we might as well make this plain by giving it to the new ones expressly-for rules to guide them would not guide them. Another criticism commonly advanced against realists is that, without rules, how do we know who are officials , for they are they not appointed according to rules? To this, it might be answered that we have psychological triggers of various kinds which makes us view individuals acting in certain formal ways as dispute –settling officials. Llewellyn on Institutions and “Law-Jobs”-see Lloyd The functional approach to law adopted by Llewellyn is well brought out by his treatment of law as an institution. The institution of law ins our society is an extremely complex one, consisting not only of a body of rules organized around concepts and permeated by a large number of principles. An institution has jobs to do, and the important thing is to see that these jobs are well and effectively carried out. Much of Llewellyn’s interest has been centered upon what he calls the ways in wchi in various types of community, the “law –jobs” are actually carried out. “Law-jobs” are Llewellyn’s way of describing the basic functions of the law, which , for him, are two-fold: “to make group survival possible”, but additionally , to “quest” for justice, efficiency and a richer life. He lists the law jobs as : the disposition of law “trouble-cases”, which Llewellyn belived was common to all systems at whatever stage of development; “preventive channeling”-the reorientation of conduct and expectations to avoid trouble; The provision of private law activity by individuals and groups , such as the autonomy inherent in a law of contract; and “the say”-the constitutional provision of procedures to resolve conflict, much in the manner of Hart’s “rules of adjudication.” According to Llewellyn, the first 3 jobs described “bare bones” law, but out of them may emerge, though he gives no indication how, the additional “questing” phrase of the legal order. For him, the problem was thus finding the best ways to handle “legal tools to law-job ends.” Llewellyn sees these “law –jobs” as universal. What this overlooks are dimensions of structure and power which are different in different societies. The quest for universality leads Llewellyn to concepts of a high level of abstraction. He also leaves as with numerous questions unanswered. E.g. is a question about the relationship between the different “law-jobs”. THE COMMON LAW TRADITION In Llewellyn’s book, the The Common Law Tradition, he develops the idea of a craft in considerable detail, as applied to the juristic method. The aim of the book is to deal with what it describes as a “crisis of confidence within the Bar”, concerning especially the question whether there is a reasonable degree of “reckonability” in the work of US in the work of US appellate courts. PAA JOY Llewellyn argues that there is a large measure of predictability in case-law, and this he attributes to the geneneral craft of decision-making in the common law tradition. In the common law, says Llewellyn, the practice of the courts has fluctutated between two types of style which he names the Grand Style and the Formal Style. The Grand Style is based essentially on an appeal to reason, and does not involve a slavish following of precedent; regard is paid to the reputation of the judge deciding the earlier case and principles is consulted in order to ensure that precedent is not a mere verbal tool, but a generalization which yields patent sense as well as order. Under the so-called Formal Style , on the other hand, the underlying notion is that the rules of law decide the cases; policy is for the legislature, not for the courts, and therefore this approach is authoritarian formal and logical. The Grand Style is also characterized by resort to , what Llewellyn calls , “situation sense”; the Formal Style, on the other hand, is not so concerned with social facts. Further, the Grand Style is concerned with providing guidance for the future far more than is the Formal Style. Llewellyn argues that in recent times, the American appellate courts have been moving steadily back towards the earlier type of Grand Style, and it is this tendency which has misled the legal profession into thinking that there is a higher measure of unpredictability in their decisions than there was in the previous more formal period. This Llewellyn attributes to a misconception as to the ways in which the court uses precedent and the tremendous “leeways” which are afforded by the system of precedent, whatever particular period style may be in operation. There are two rather curious and unexpected features in Llewellyn’s last book which deserve some comment. According to Llewellyn, it is a feature of the Grand Style , which he warmly approves , that the courts proceeds to arrive at decisions in relation to what he calls “situation sense.” It is exceedingly difficult to grasp exactly what the author has in mind by this concept. Under the Grand Style, Llewellyn seems to be saying that insight and wisdom is developed whereby judges will achieve a kind of reasonable criterion, though not one which can be specifically formulated, and so arrive at a wide measure of arrangement as to what are the appropriate legal solutions both worthy of approval by the community and likely, in fact, to be approved by the community. This may or may not be true in relation to particular periods or particular legal systems, but it seems a very far cry from the scientific realism movement. Moreover, Llewellyn does not seem to face up to the fact that in many communities, certainly including his won, there may be vital issues involving conflicts of vlues between different groups and interests in the community; how hten can there e any objective core of insight which can produce decisions appropriate to reconcile all this welter of confusion? It may well be that a more honest decision will be produced by a judge who approaches the question in the spirit of the Grand Style rather than looking at the matter through the spectacles of formalism. All the same, Llewellyn seems unduly optimistic when he claims that what he calls “the law of the singing reason” will tend to produce a rule yieldin regularity, ‘reckonability” and justice all together. It is fair to add however that, Llewellyn does not put his case higher than saying that the Grand Style is likely to produce a greater proportion of such decisions than any other style. The second rather curious feature in this book is that the author confines his evidence exclusively to the material which appears from the actual decisions of appellate courts. He recognizes that these do not disclose the whole truth of what he calls “the facts of life” , but he insists that these provide adequate materials for revealing the techniques of the courts, especially if one employs his chose procedure, not of examining cases according to their subject –matter , but in the order they happen to be reported in the volumes of report relating to particular courts. But he insists we must learn to read these cases, not PAA JOY for what they decide, but for their “flavour.” He urges that we should not look to “what was held” but rather to “what was bothering and helping the court.” Here, we now find Llewellyn is far form renouncing any of his earlier enthusiasms. It is a little disarming to find that what started as a rather revolutionary movement has ended up fundamentally as an appeal for a common-sense approach to law. Scientific and Normative Laws Is it a valid criticism of the realists that they ignore the purely normative character of legal rules and seek to replace these by scientific statements laying down uniformities of human conduct? This criticism is more valid in relation to Frank and some of the earlier writings of Llewellyn, but there is no doubt that later Realism as exemplified by mature Llewellyn took cognizance of the normative character of legal rules. Legal rules are norms of conduct which are in themselves neither true nor false. Yet the realist seems to be seeking to prove their truth or falsity in relation to the criteria of actual human behavior. The realist does not deny the normative character of legal rules. What he says is that these norms do not provide the complete answer to the actual behavior of courts, legal officials or those engaged in legal transactions. Admittedly, the realist predilection, following Holmes, to treat rules of law as predictions of what the court may do, seems to go counter to this. But this is because the realist is here thinking of the viewpoint of the lawyer advising his client, rather than of het norm prescribed by the judge or laid down for his guidance. If we are to understand the actual working of law in human society, it is not enough to simply pursue a collection of the relevant legal norms for these tell us but little about actual “legal behavior”, in the sense of how legal business is in fact transacted. A follower of Kelsen might say that this is outside the field of true legal science. The kelsenite concentrates on his norms , the relaist on his facts of society, each regarding the other’s activity patronizingly as a peripheral study on the fringe of his own central sphere. Yet, it may be suggested that both equally represent essential aspects of the legal process is an overall picture is to be taken of law. Achievements of the Realists-See Lloyd Whereas the early realists employed the social science as an appendage, using them to no profound effect, the modern inheritors of the realists tradition have become sophisticated in the techniques of the political scientist and sociologists. Also, the realists do not reject technical legal analysis, but merely emphasize that this is not in itself not enough, if we wish to understand how the law works, or how it may best be developed or improved. And if so far little has been achieved in finding any far reaching substitute for the habitual legal technique which has served lawyers for centuries, realists have played their part in bringing about a changed outlook and attitude towards the legal system and the function of the law and the legal profession in society , which has made itself felt in all but the most traditionalists of the law schools of the common law world. Where Stands Realism Today? The broader movement of realm showed signs of having passed its peak by the early 1940s, though in the sphere of jurisprudence its message not only continues but ushered in a distinctive movement which is by no means yet extinguished. Lawyers however still search for some ethical basis for law, inspired by the desire to arrive at some absolute scheme of values which can be held to support and enshrine their own sense of what is right and wrong, just or unjust. PAA JOY In 1961, Professor Yntema, a leading realist , attempted to assess the present and future of the movement. He conceded that a major defect of the movement had been neglect of the more humanistic side of law, particularly revealed both in its neglect of the comparative and historical aspects of law, and a tendency to place over –emphasis on current “local practice.” The result of this has been a certain loss of perspective , and in particular, a failure to distinguish between what is trivial or ephemeral and on the one hand, and what is of wider imort on the other. His suggestion for the future is not to abandon the critical achievements of realism, but to develop these on more constructive lines. This, he states, would involve a more humanistic conception of legal science, with due attention paid both to the systematic analysis of legal theory and of historical and comparative research. HISTORICAL SCHOOL OF JURISPRUDENCE Natural law thinking had dominated legal philosophy especially in the eighteenth century. However, two major movements arose in response to the natural law: Legal positivism and Historical or Anthropological school. The Historical School or the ‘Historical Approach’ did not agree with the theory of naturalism at the time. The Historicists believed that the question of “what is law” can be better answered if we understood the historical roots and development of the legal system of that particular society. It emphasized on appreciating the feelings and customs of the people. Thus, some called it the ‘Romantic Movement’ due to its emphasis on people’s feelings and customs. The Historical School of jurisprudence is thus concerned with the view that for law to be valid in a proper legal system, such a law must be consistent with the values, civilization, history , traditions , culture and customs of that legal system. Two main elements : National Spirit and Popular Consciousness. They argue that any law which is inconsistent with the national spirt and popular consciousness is not law. The national spirt or popular consciousness is made up of history, civilization, custom, tradition and culture. Again , the law making process involves the history plus the juristic skill. this means that when making law, it must first mirror the history of the country. After the law reflects the history, it goes into the juristic skill –this is the law making process. So if there is law in the juristic stage without first clearing the history, then that law is not law. The juristic stage makes them look like positivists but they are not necessarily positivist because of their national consciousness affair. They may be deemed positivists however because to them , law does not transcend the state. DISADVANTAGES They may be criticized in respect of a state which has been conquered. For instance in 2000, when U.S. conquered Iraq. Many of the laws passed in Image had an American face. Under such circumstances you cannot suggest that there was no law in Iraq at that time. Secondly, there could be an imposing culture. Which culture is it going to reflect? Is it the external or local culture The third is globalization. We are increasingly being influenced by others. In fact culture is dynamic It is difficult for them to make a case for the essence of judicial input in law PAA JOY Advantage: Many of the laws enacted are a reflection of history. The human rights provisions show how we have been denied human rights by our colonial masters. Remember the purposive approach to interpretation adopted now. –consider section 69A of Act 29 which criminalizes female genital mutilation ; Infact it is not for nothing that customary law has been recognized as part of the sourcs of laws in Ghana under Article 11(3) of the 1992 Constitution ‘the rules of law which by custom are applicable to particular communities in Ghana’ Herder : This new school was most prominent in Germany where many of the school’s leading figures emerged from. One of the most influential founders was Herder. Herder rejected the universalizing tendencies of the French philosophs (the famous French philosophers at the time such as Voltaire, Montesquieu, Rousseau and Diderot) and rather stressed the unique character of every historical period, civilization and nation According to Herder, every nation possessed its own individual character and unique qualities and no nation was superior to others. Consequently , any attempt to unite these different national qualities and character through the use of a general command of a universal natural law based on reason will be problematic. It will limit the free development of each national spirit (the Volksgeist). It will also impose a crippling uniformity on the spirit of the nation.-though he makes sense cant u counter it with the argument that in the same vein within each particular community in the nation, there are distinct cultures which are practiced and so an attempt to merge all these cultures to bring out the law may reflect a particular society to the neglect of another. Herder believed that rather than history and law of their time to be concerned with the exploits of kings, generals, states men and great men so called it should instead focus on the life of communities. He argued that different cultures and societies developed their own values rooted in their own history , tradition and institutions , and the quality of their life is expressed in their daily values so each society must be allowed to freely develop on their own without imposing rules and commands over them. Herder was not a fan of the bureaucratic state. He believed it “robbed men of themselves” and substituted human life and feelings with ‘machines’. Hegel: Hegel, another German who was a disciple of Herder, was a historicist alright but he took it from a different angle. He argued that the individual is of no value by himself. The state is the highest form of ethical life. The state transcends but also incorporates , the interests of its individual members and of intermediate social forms, such as family and civil society. According to Hegel , the individual finds fulfillment in playing a proper role in that state. He believed that the state overrides individual interest. He argued that when there was a conflict between the state’s interest and individual interest, the solution lied in the state giving a conscious direction. He did not endorse autocratic rule in a state but he saw the state as the vehicle to be used in securing national freedom. To show he did not endorse authoritarianism, Hegel was a strong critic of the Prussian State (the powerful German state in the early 19th century) which was in power , for not giving room for the opinions of individuals and groups in the state. PAA JOY According to Lloyds, “introduction to Jurisprudence”, 8th edition, ideally every developed nation was an absolute end –in-itself, enjoying total sovereignty and autonomy from its neighbors. As such an unfortunate development arose basing on his theories which Hegel did not anticipate, emerged, according to Lloyds. A chauvinistic nationalism in the 19th century ignored Hegel’s stress on freedom as the essence of the state, it rather distorted his philosophy and glorified authoritarian rule as superior to the interests and spirit of individuals in the state. This distortion believed in the state using war as a means of national achievement. Hegel’s emphasis on the sate later became the foundation and inspiration upon which another German , karl Marx built his theory of Communism. Von Savigny : He believed there was an organic connection between law, people’s custom and spirit as developed through history. To him, the true “living law” is customary law, which is not given by a king’s arbitrary rule, but from the “internal , silently-operating forces” within the community. Savigny saw legislation as secondary in importance to custom. (this will be doubted in Ghana by the combined effectd of Article 1(2) and 11 of the 1992 Constitution) He developed three stages: The first stage of law is custom , originating from the values of the people; second stage is the addition of juristic skills which codify the expression of the volksgeist ( a unique, ultimate and often mystical reality) and then a stage where a nation is in decline so law loses its relevance and ultimately a loss of national character. “Law grows within the growth, strengthens with the strength of the people, and finally does away as the nation loses its nationality”, Von Savigny argued. Henry Maine : English Jurist and legal historian, Henry Maine also did not agree with the rationalizing theories of the naturalists which were prominent in his time. He was influenced by the work of Von Savigny. Maine’s however , was without the ‘mystery’ associated with the leading figures of the German Historical School. His work on seeking to find out what law is led him to study history and document hitherto unknown cultures of his time. He studied and wrote at a time that man’s knowledge of early society was scanty. He opposed the existing theories of the “law of nature” and he did not see legal systems as appropriately reflecting man’s rational nature. He was more concerned with man’s deep instincts, emotions and habits. He studied the early law of Greece, Rome, the Old Testament and the native law of India. He particularly saw India as “the great repository of ancient juridical thought” and Henry Maine was able to make theories about unexplored territories like India to contribute to the idea that the law of a people should be reflective of their custom and values. HE researched into ancient history and unexplored cultures and used it to make general assumptions at the time. As such his ideas were backed by empirical data he hadgathered from the cultures he had studies, a marked difference from the figures of the German Historical School. Whereas the German Historical School theorized, Maine introduced scientific evidence-based ideas into the law at the time. Maine’s theory was called the ‘organic theory’. He came up with three stages in the early development of law in any society. First, law is confined to the personal commands of rulers thought to be divinely inspired. In the second stage, the command crystalizes into custom. The customary law is explained to society by a few privileged people like the Roman Pontiffs and India Brahmins. The third stage is when the majority revolts against the ruling minority and consequent publication of a code. AT this stage the law ceases to develop as codes are instituted and venerated. Mine explains that beyond this stage, static societies do not progress PAA JOY while progressive societies go on to develop further laws which will then be unified in a consistent and scientific fashion. Maine’s work has influenced legal anthropology up till today. But according to Pospisil, Henry Maine’s contribution to jurisprudence is not in “the empirical, systematic, and historical methods he employed to arrive at his conclusions, and in his striving for generalizations firmly based on the empirical evidence at his disposal…he blazed a scientific trail into the field of law, a field hitherto dominated by philosophizing and speculative thought”. The works of Henry Maine and German Historical School’s leading figures, despite employing different methods, have left many legacies for jurisprudence. For example, HLA Hart developed his idea of a legal system from a primitive society while Hans Kelsen’s norm –chains go back to the very first constitution. While the German historical School’s leading figures theorized about valuing the role of the individual in a legal system in a state rather than been subject to commands from the sovereign , Henry Maine studied ancient customs and brought empirical and scientific data to justify the role of history of a people in guiding the formulation of law in a society.