Harappan Civilization: History, Culture, and Urbanization

advertisement

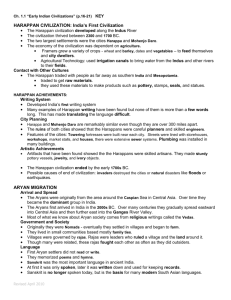

The Harappan Culture The extensive Harappan civilisation spanned from late circa 3000BC to 750BC. This is the period when northwestern India and Pakistan embraced a distinctive form of a Bronze Age urbanisation. Despite being stretched across 1022 sites (of which 616 were located in India), only 97 of them have been excavated. With new sites being discovered and old ones being reexcavated, our knowledge of the Harappan civilisation is still evolving. Through radiocarbon determinations, archaeologists have categorised the chronology of this time period into preHarappan, matured Harappan and post-Harappan civilisations. The Mature Harappan entails the growth of a cultural tradition that extends back to the starting of village farming communities and pastoral camps (Possehl, 2000). The Harappans then became the largest ethnic group in the Indus Valley. Its organisational complexity led to a rapid territorial expansion (Shaffer and Lichtenstein 1989: 123). Urbanization was the most prominent marker of the sociocultural intricacies of the Matured Harappan. Houses and fortified settlements were a common feature of the Harappan civilization. The houses in villages were made from mud-bricks, reeds and stones for drains. Cities had buildings made of burnt and sun-dried bricks (Singh, 2008). Floors were made of hard-packed earth and covered with sand, while doors (as per clay models) had simple carved designs on them. Houses were interconnected by elaborate drainage systems and were arranged along a grid structure. The Harappans also made organised arrangements for bathing and drinking. One of the most famous structures is the Great Bath. With water-tight bricks and thick bitumen on the floor, this is one of the earliest signs of waterproofing in the world. The purpose of the Great Bath is still not confirmed, however, the emphasis on providing water at bathing sites could suggest a religious reasoning. Wells were also frequently used (particularly in Mohenjadaro), along with other sources of water like cisterns and reservoirs. Harappa also had post-cremation burials for funerary practices. Elevated citadels were used for public rituals and civic life; the citadel complex at Kalibangan interestingly has mud-brick platforms and is referred to as a ‘fire altar’ (Upinder, 2008). The complex urbanised structures of the Harappans thus indicate a broad range of social customs, religious beliefs and practices. Agriculture was also practiced at multiple Harappan sites, the most important domesticated animals being cattles and buffaloes. Presumably, these domesticated animals were used for meat, wool, milk and as pack animals. Figurines indicate that elephants, tigers, rabbits, dogs and monkeys (amongst other animals) were found as well. Two-wheeled carts were used to transport goods and people, this has been depicted by multiple terracotta models. The most commonly grown crops were wheat, rice, millet, barley and legumes. Goods were carried across large distances by carts using oxen and donkeys to transport the merchandise. Horses were not frequently used. Common routes of trade were Baluchistan, Sindh, Rajasthan, Punjab, Gujarat and upper doab as indicated by settlement patterns and distribution of materials/products. Semiprecious stones, seals, textiles and metal are some examples of goods that were traded. For example, Lapiz Lazuli was probably imported from Afghanistan, Jade from Turkmenistan, Tin from Kazakhstan and chlorite from the Persian Gulf. However, barely any West Asian artefacts have been found in Harappan contexts. Harappan seals are a very remarkable artifact when unraveling the story behind the civilization. While Harappan seals were primarily used for stamping packages which were to be traded, they bore religious and mythological motifs of great artistic quality. Sealings shaped like date-seed, heart, shield, writing board and hare, fish, etc were found only at Harappa in the Matured period. Pipal trees were a recurring theme in these square seals as well (Dhavalikar & Atre 1986). Because the trees were 7 in number, it is speculated to have connections with later beliefs in the seven rishis or seven mothers. The most commonly repeating animals were the elephant, rhinoceros, buffalo, tiger and two composite animals; often identified as deer or hill goat in most seals they are seen eating from a trough. Many silver mythical one-horned animal or unicorn seals were also found at Mohenjodaro (Atre, 1985). The average size of the seals were around 2.54cm and were made of steatite. Stone seals were made by carving them with drills and chisels. There were usually short inscriptions on each seal, however, the script has not been deciphered as of yet. The texts/pictographs are very limited in nature, and there are no clearly recognizable word dividers which would have possibly helped in analysing its meaning (Parpola, 1986). Considering these difficulties, it isn’t very surprising that the decipherment of the Indus script still remains unsolved. However, it is known that the script is read from right to left. Harappans had a high level of expertise in craftsmanship such as stone working, metal crafting, pottery and bead making. The pots were made in funnel-shaped kilns and were usually black-on-red (sometimes grey and buff too). Elaborately painted pots may have been used by those of the upper-class during ceremonies. Ivory carvings, beads, bracelets all demonstrate the Harappans expertise in shell working. Bangles were made from conch shells. Bone-working was another form of making beads, pins and awls. One of the most famous figurines is the “dancing girl” found during the 1926-1927 excavations. She was made using the lost-wax method. Farmers, hunter-gatherers, craftspeople, sailors, ritual specialists, brick masons, sculptors, shopkeepers, garbage collectors, merchants and fisherfolk were some of the many occupations during the Harappan civilisation. While there may have been some form of centralised control or class structure, the absence of armies, court officials and priest-kings suggest there could have been a diffused administrative authority (Fairservis, 1967). Given the vast forms of craftsmanship, trade, agriculture and urban settlements, it is fair to say that the Harappan civilisation was one of the most prominent and influential settlements in history. Works Referenced: Possehl, G. L. (2000). The Mature Harappan Phase. Bulletin of the Deccan College Research Institute, 60/61, 243–251. http://www.jstor.org/stable/42936618 Parpola, A. (1986). The Indus Script: A Challenging Puzzle. World Archaeology, 17(3), 399–419. http://www.jstor.org/stable/124704 Shaffer, J.G. and Lichtenstein (1989). Ethnicity and Change in the Indus Valley Cultural Tradition, in Old Problems and New Perspectives in South Asian Archaeology (J.M. Kenoyer Ed.), pp. 117-26. Madison: Wisconsin Archaeological Reports, 2. Singh, U. (2008). History of Ancient and Early Medieval India: From the Stone Age to the 12th Century (1st ed.). Pearson India Education. Dhavalikar, M. K. and Atre, Shubhangana 1986 Fire Cult and Virgin Sacrifice - some Harappan rituals. Paper read at the International Seminar on South Asian Archaeology, University of Wisconsin, Madison. November 1986 (In Press) Atre, S. (1985). THE HARAPPAN RIDDLE OF “UNICORN.” Bulletin of the Deccan College Research Institute, 44, 1–10. http://www.jstor.org/stable/42930107 Fairservis, W. A (1967). The origin, character, and decline of an early civiliza- tion. New York, American Museum Novitates. In press GADD, C.J