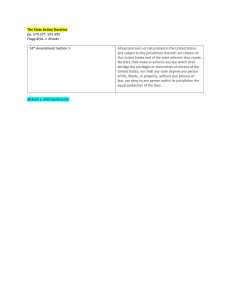

Part I Limits of Federal Jurisdiction And Part II Use of Special Appearances Memorandum For 28 U.S.C. § 2255 Memorandum Of Points And Authorities With Argument Note: Jurisdiction should be challenged in all municipal, state and federal matters immediately because if it is not done so before trial or first pleading you can not bring it up again as you have admitted the jurisdiction of the court. The special appearance must be used in challenging jurisdiction. Part I Limits of Federal Jurisdiction POINT I - THE CONSTITUTION OF THE UNITED STATES IS A GRANT OF LIMITED POWERS TO THE FEDERAL GOVERNMENT The delegates to the Constitutional Convention, prior to the formation of our union of states, were very jealous of their power to rule themselves as states. And there was much argument as to how much power the individual states should relinquish in order to form a Union for their mutual good. Even a modest review of those proceedings will prove that this is solid doctrine. After the successful conclusion of the Convention and some years after the Union was effected (1829) Chief Justice Marshall stated: "This government is acknowledged by all, to be one of enumerated powers. The principle, that it can exercise only the powers granted to it, would seem too apparent, to have required to be enforced by all those arguments which it’s enlightened friends, while it was depending before the people, found it necessary to urge; that principle is now universally admitted." McCulloch V. Maryland; 4 Wheat 316, 405 (1819) Defendant finds in Black’s Law Dictionary; Revised Fourth Edition (1968) that the word "enumerated" is defined as "mentioned specifically or designated or expressly named or granted." So it is an inescapable conclusion that the three branches of government have limited and enumerated powers. And this leads very nicely into the second question presented. 1 POINT I I - IS IT NECESSARY FOR THE FEDERAL COURTS CREATOR, CONGRESS, TO SPECIFICALLY DESIGNATE, AS A CRIME, ACTS OR OMISSION OF ACTS: AFFIX A PENALTY: AND SPECIFY OR CREATE A COURT TO EXERCISE JURISDICTION? In view of the comments of Justice Marshall above and the definition of enumerated, it would seem unnecessary to argue this point. However, the District Court may think defendant is making a worthless motion so additional argument follows. During the early years of our nation the judges of the Federal Courts were very careful to avoid overstepping their enumerated powers. It made no difference whether a party to a suit was trying to get the courts to claim jurisdiction or whether the party was arguing the validity of the jurisdiction claimed. In each case the courts were very careful to note whether the jurisdiction had been specifically written into the particular statute that was the cause of the suit. And periodically they would make a general statement that indicated their overall philosophy on the subject. As, for instance, when the Supreme Court stated in 1812: "The legislative authority of the Union must make an act a crime, affix a punishment to it, and declare the Court that shall have jurisdiction. Certain implied powers must necessarily result to the Courts of 4 Justice from the nature of their institution. But jurisdiction of crimes against the state is not among those powers. U.S. U. Hudson; 11 U.S. 7 (1812) The United States District Court for the Eastern District of North Carolina is assuming jurisdiction, in this case, by implication. And, obviously, that is not allowed. Defendant was not aware of the jurisdictional issue at the very beginning of this case. However, neither the U.S. Attorney nor Judge Whelan has made any statement as to the source of the jurisdiction. Except for the original jurisdiction of the Supreme Court, which comes from the Constitution, two prerequisites must be present; first, the Constitution must have given the Courts the capacity to receive it and second, an act of Congress must have conferred it Defendant acknowledges the capacity of the District Courts to receive this jurisdiction but argues that no "Act of Congress" conferring jurisdiction has ever been passed concerning violations of USC 26. Congress went to the trouble to grant civil jurisdiction via 28 USC Sec. 1340. But because of the far greater penalties involved in criminal charges versus civil charges, it is far more important for Congress to spell out in detail the jurisdiction involving any charge that is claimed to be criminal in nature. Early in our history (1799) a comment was made on this aspect of the problem: "If Congress has given the power to this court, we possess it, not otherwise; and if Congress has not given the power to us, or to any other court, it still remains at the legislative disposal." 2 Turner U. Bank of North Carolina; 4 Dall 8, 10 (1799) Defendant states that jurisdiction over violations (other than civil) of USC 26 is still at legislative disposal. Congress could state that all violations of USC 26 are criminal offenses; set penalties to each offense; and state that Federal Courts have jurisdiction, whether the offense is a misdemeanor or felony. And if they did this, the citizen would have his Constitutional rights preserved. but that is not the case now when courts claim jurisdiction because their despotic actions would be at an end if they had to carry on under explicit and firm criminal regulation. And the irony of this is that Defendant must take on the obligation of the U.S. Attorney and the court and prove that they do not have jurisdiction. This method of conduct was ruled out many years ago. "The jurisdiction of this court is not prima facie general, but special. (b). A man must assign a good reason for coming here. If the true fact is denied, upon which he grounds his right to come here, he must prove it. He, therefore, is the actor in the proof; and, consequently, he has no right, where the point is contested, to throw the onus probandi on the defendant." Max field ‘s Lessee V. Levy (1); 4 U.S. 330 (1797) POINT III - HAVE THE FEDERAL DISTRICT COURTS BEEN GRANTED THE POWER TO ADJUDICATE CIVIL STATUTES IN CRIMINAL COURT CASES? Defendant has searched far and wide and been unable to find any such grant of power. Defendant concedes (again) that the Federal Courts have jurisdiction over civil cases via USC 28; Sec. 1340. But criminal-no. Defendant offers the following chart; of the American Law System, see page 87, to substantiate this theory. From this one can only conclude that there is no mixing allowed and there can be no such thing as a criminal offense supported by civil statutes. And neither can there be a civil violation of criminal laws. And the conclusion would of necessity be that Congress does not have the power to grant criminal jurisdiction to any court over cases based on civil statutes. Congress would first have to make violations crimes. And when Congress did this the statute would no longer be civil in nature. POINT I V - HAS CONGRESS SPECIFICALLY DESIGNATED, AS CRIMES, VIOLATIONS OF U.S.C. 26; AFFIXED A PENALTY TO SUCH VIOLATIONS; AND DESIGATED OR CREATED A COURT TO EXERCISE THE JURISDICTION? The answer to the above is a resounding no to the question of a grant (specifically) of jurisdiction to the Federal District Courts; nor did they create a new court to exercise such jurisdiction. As Chief Justice Mar-shall said in 1829 in McCulloch V. Maryland (Supra) 3 "This government is acknowledged by all, to be one of enumerated powers." Congress would have to state that Federal District Courts are to have criminal jurisdiction of all cases in violation of U.S.C. 26. Then that jurisdiction would be "enumerated." But Congress has not done this. Congress, if it wished could create a new court with perhaps the name Federal Income Tax Violation courts and grant them the jurisdiction to try all cases of a criminal nature that arise in violation of the Income Tax laws. But it has not done this either. So Congress still has the jurisdictional issue within it’s power to grant and no one has the enumerated power of jurisdiction of criminal charges in U.S.C. 26 violations. Defendant concludes that the Internal Revenue Service, an Administrative Agency, has perpetrated a gigantic hoax, or perhaps even a crime, against the American citizens by charging citizens with so called crimes that may not in fact be crimes, and bringing suit against such citizens in courts without jurisdiction to try the cases. Defendant moves to vacate the sentence and to dismiss the action for lack of jurisdiction. Defendant further moves for an order directing the Internal Revenue Service to return all papers and records obtained from defendant; and that the Internal Revenue Service be enjoined from instituting any more indictments of a criminal nature that are supported by civil statutes; and that the Internal Revenue Service be enjoined from using any information obtained via their investigation of Defendant as a result of this case in any action against Defendant in the future The following citations are submitted in support of Defendant’s challenge to the jurisdiction of the District Court, Eastern District of North Carolina to hear a criminal case in which the act alleged committed was supported by civil statutes and a court of jurisdiction was not specifically enumerated in any statute. There are so many court cases supporting this challenge that Defendant could fill volumes. Defendant researched cases, primarily, that came about in the early life of our nation because most jurisdictional arguments were quickly raised during that period of our National life. The early cases show that the Supreme Court acknowledged that Congress was the creator of the Federal District Courts and that the Courts had no power other than that which was specifically given them by Congress The Supreme Court stated in various language phrases that it was necessary for Congress to specifically designate an act or omission of an act, a crime, then affix a penalty for a violation; and finally Congress had to specifically designate the court (or create a new court, should they wish) to exercise the jurisdiction of these cases. For a first example, in 1807 the Supreme Court through Chief Justice Marshall stated: "As a preliminary to any investigation of the merits of this motion this court deems it proper to declare that it disclaims all jurisdiction not given by the constitution, or by the laws of the United States. . Courts which are created by written law, and whose jurisdiction is defined by written law, cannot transcend that jurisdiction. . .To enable the court to decide on such questions, the power to determine it must be given by written law." 4 Exparte Boliman & Swartwout; 8 U.S. 75, 93, 94 (1807) Defendant is of the opinion that his motion to vacate is valid and should not be over-ruled because the District Court is of the opinion that jurisdiction is implied. But this is not allowed as brought out in the following case: "The legislative authority of the Union must first make an act a crime, affix a punishment to it, and declare the Court that shall have jurisdiction of the offense. Certain implied powers must necessarily result to our Courts of justice. .But the jurisdiction of crimes against the state is not among those powers." Hudson v. Goodwin; 7 U.S. 32, 33, 34 (1812) The requirement that powers had to be enumerated has had support universally by the courts and was recognized early in our Nation’s life: "The principle that it can exercise only the powers granted to it. . .is now universally admitted." McCulloch v. State of Maryland; 4 Wheat 316 (1819) And earlier (1797) the Supreme Court stated somewhat indignantly: "No Court in America ever yet thought, nor, I hope, ever will, of acquiring jurisdiction by a fiction. . .it is evident that we are not to assume a voluntary jurisdiction, because we think, or others may think, it may be exercised innocently, or even wisely. The Court is not to fix the bounds of its own jurisdiction, according to its own discretion. A jurisdiction assumed without authority, would be equally an usurpation, whether exercised wisely, or unwisely." Maxfield’s Lessee v. Levy (1); 4 U.S. 308, 311, 312 (1797) The early decisions evidence a desire on the part of the Supreme Court to be absolutely sure that they made no errors in accepting or rejecting jurisdiction. "Before we can look into the merits of the case, a preliminary inquiry presents itself. Has this court jurisdiction of the case." The Cherokee Nation v. The State of Georgia; 5 Peters 2, (1831) After much investigation and discussion the Court decided that the Cherokee tribe was not a foreign state as contended, and therefore the Constitutional recital of jurisdiction was lacking. 5 Again the Supreme Court refused jurisdiction in a case because it had not been granted by the statutes on which the case rested: "Of course, it has not been conferred on the District Court of Alabama by the act establishing the bank of the United States.,’ The Bank of The United States v. Martin; 5 Peters 478, 480 (1831) They could not find the grant of jurisdiction in the statutes, so they refused to judge the case. The District Court in the subject case may think that the jurisdiction issue might be "worthless." This was made without any argumentation. However, throughout the cases researched by defendant it is obvious that the Supreme Court deemed the issue anything but "worthless." The Supreme Court considers the issue of the utmost importance and that the grant of jurisdiction must be written and specifically stated. This attitude is evident in a 1834 case: "The decisions of this court require, that the averment of jurisdiction shall be positive, that the declaration shall state expressly the. fact on which jurisdiction depends. It is not sufficient that jurisdiction may be inferred argumentatively from its averments." James Brown V. Richard Keene; 33 U.S. 112, 115 (1834) Yet the Court in the subject case states that jurisdiction is available to it, without proof, even when challenged. And may think my motion is "frivolous." The various Supreme Courts down through the years used different words to convey the seriousness of this issue but all came to the conclusion that it was very important, and certainly not frivolous. Note the following: .... this Court is one of limited and special original jurisdiction, its action must he confined to the particular cases, controversies, and parties over which the constitution and laws have authorized it to act; any proceeding without the limits prescribed is coram non judice, and its action a nullity." The State of Rhode Island et al. V. The Commonwealth of Mass. 37 U.S. 657, 719 (1838). Defendant asks if that sounds like they think the issue of jurisdiction is "frivolous." In the subject case the District Court, without showing a grant of jurisdiction, accepted a plea of guilty although it has absolutely no jurisdiction. Defendant objects to this action which has caused him much aggravation and monetary expense and says it never should have happened. 6 Again, the Supreme Court was careful to search out the Congressional statute upon which the case rested and after doing so refused to take jurisdiction with these words: "The power of the Supreme Court, in this respect, is carefully defined and restricted by the act of 1789; and it is our duty not to transcend the limits of jurisdiction conferred upon it" Zenas Fulton V. Morgan M’Affee; 41 U.S. 149, 152 (1842) Defendant would suggest that the District Court not "transcend the limits of jurisdiction conferred upon it" also. Jurisdiction was not specifically given, so the Supreme Court refused jurisdiction in 1879 with these words: Congress, having the power to establish the courts, must define their respective jurisdictions. . also, that, having a right to prescribe, Congress may withhold from any court of its creation jurisdiction of any of the enumerated controversies. Courts created by statute can have no jurisdiction but such as the statute confers." Sheldon et al V. Sill; 49 U.S. 441, 448, 449 (1850) But Defendant is unable to find a grant of jurisdiction to the federal district courts in the statute -U.S.C. 26, as far as criminal jurisdiction is concerned. The Supreme Court refused jurisdiction in two cases in 1879 pertaining to the monetary amount of claims by the parties in the case. They. found that the amount in question was less than that called for in the statutes. These cases were: Railroad Company v. Trook and Nagle V. Rutledge: 100 U.S. 112 and 675. These could be called "frivolous" because a quick reference to the statutes could determine the issue, yet the Supreme Court considered them. In 1883, the Supreme Court again searched out the language of the statute (18 Stat. 470) to see if jurisdiction was conferred and when they found that it had not been granted they refused to assume jurisdiction; Claflin V. Commonwealth Insurance Company; 110 U.S. 81, 88 (1883). Also see Rosenbaum V. Bauer; 120 U.S. 450 (1887), indicating that they looked for the written word to convey jurisdiction. And since it was not there, they refused to consider the case. Different language was used to convey the same idea in an 1888 case: "Here we are bound by statute; and not by the state statute alone, but by an act of Congress, which obliges us to follow the state statute and state practice. The Federal Courts are bound hand and foot, and are compelled and obliged by the Federal legislature to obey the state law." 7 Amy V. Watertown; No.1: 130 U.S. 301, 320 (1888) Defendant asks, are the Federal District Courts no longer "bound hand and foot", but free to take jurisdiction by implication (without enumeration), assumption or other reason they might choose? Defendant does not believe that they have this type of freedom. Defendant is of the opinion that the Federal District courts are still bound by the statutes. And the statutes in the subject case (USC 26) do not confer criminal jurisdiction on the Federal Courts or any other court. In 1890 the Supreme Court again verified the rule of the statutes: "The criminal jurisdiction of the courts of the United States is wholly derived from the statutes of the United States." Manchester V. Massachusetts: 139 U.S. 240, 262 (1890) The word wholly as used here means without exception. And so that includes U.S.C. 26. In addition to being "wholly" derived from the statutes, the courts repeat the message that the language must be specific; in an 1892 case: .... crimes and offenses, cognizable under the authority of the United States, are such, and only such, as are expressly designated by law; and that Congress must define these crimes, fix their punishment, and confer the jurisdiction to try them." In Re Greene, 52 Fed. Reporter 104, 111 (1892) Again, Defendant points out that U.S.C. 26 does not "expressly" confer criminal jurisdiction on Federal District Courts or any other court. In more recent times (1922) the Supreme Court again commented in very succinct terms the conferring and the reception of jurisdiction: "Only the jurisdiction of the Supreme Court is derived from the Constitution. Every other court created by the general government derives its jurisdiction wholly from the authority of Congress. That body may give, withhold or restrict such jurisdiction at its discretion, provided that it be not extended beyond the boundaries fixed by the Constitution. . The Constitution simply gives to inferior courts the capacity to take jurisdiction in the enumerated cases, but it requires an act of Congress to confer it. Kline et al V. Burke Construction Company; 260 U.S. 226, 234 (1922) Defendant claims that if Congress does not expressly, which means in writing, give some specific court jurisdiction pertaining to violations of a statute then that jurisdiction is withheld-perhaps unintentionallybut nonetheless withheld. 8 Furthermore, as Defendant wishes to point out to this court, civil codes or statutes were never intended to prescribe criminal penalties, because they cannot be enforced in civil complaints. THE DISTRICT COURT DOES NOT HAVE JURISDICTION OVER OFFENSES AGAINST THE UNITED STATES, OTHER THAN OVER THOSE OFFENSES LISTED IN USC 18. Defendant grants that the power to exercise jurisdiction over those crimes listed in USC 18 has been granted via 18 USC 3231. However, Defendant denies that this grant extends to Title 26. Apparently, the U.S. Attorney relies solely on 18 USC 3231. Defendant is of the opinion that this argument is built on a foundation of sand. Under 18 USC Annotated we find "History: Ancillary Laws and Directives" and under this heading we find the following quote: "This section was formed by combining former 18 USC Paragraph 546 & M7 with former USC Paragraph 58&i, with no change of substance." The words ‘no change of substance’ means that the essence of the statute remains as before. Let us see what the statute was before. Paragraph 546 Title 18 (1940 Edition) states: "The crimes and offenses defined in this title shall be cognizable in the district courts of the United States, as prescribed in Sec. 41 of Title 28." (The underlining emphasis is mine.) The words ‘in this title’ refer to Title 18. They are restrictive words that limit the jurisdiction to only those crimes listed herein. This language is anything but "unequivocal" as claimed by Plaintiff’s attorney. Defendant will phrase this in syllogistic form: Major premise: 18 USC 3231 grants jurisdiction only over those crimes listed in 18 USC, to district courts. Minor premise: But, the alleged crime in this case is not listed in 18 USC. Therefore: The district courts do not have jurisdiction over the alleged crime in this case. And we must conclude that any argument presented by Plaintiff’s attorney to the contrary is without merit. Furthermore, if Plaintiff’s attorney claims that the language was "unequivocal" then it would be unnecessary to itemize other jurisdictional issues. Yet we find in Title 18, 1940 Edition, the following situations over which Congress felt it necessary to specify or enumerate the jurisdiction: Paragraphs: 3633 regarding the enforcement of summons, 3723 regarding 9 forfeiture, 3744 regarding suits to collect taxes, 3746 regarding suits for erroneous refund and 3800 granting jurisdiction to issue orders, processes and judgments. Defendant is of the opinion that five years (possible) of his liberty is far more important than the issuance of "orders, processes and judgments." Therefore, the only prudent conclusion is that such an important issue must be specifically granted by Congress in writing. For this second reason, Plaintiff’s attorney has no valid response to this. Defendant denies Plaintiff’s claim that Congress has given district courts the power to levy criminal penalties for certain tax crimes. Defendant agrees that Congress has assigned criminal penalties to certain actions in violation of USC 26. However, Plaintiff’s attorney cannot point out the statute that gave the District Courts the power to levy these penalties. Defendant wishes to point out that the Supreme Court had said soon after our nation was founded (1812) that Congress ". . .must declare the court that shall have jurisdiction of the offense." U.S. V. Hudson; 11 U.S. 7. And the word ‘declare’ is defined in Webster’s Dictionary of 1828 "To make a declaration to proclaim or avow one’s opinion or resolution in favor or in opposition; to make known explicitly some determinations." And Congress has not made known explicitly what court, if any, is to have jurisdiction over crimes supported by non-criminal statutes. Plaintiff’s attorney may conclude that all the various Supreme Courts were unaware that Article III, Section 2, Paragraph I stated: "The judicial power shall extend to all cases, in law and equity, arising under this Constitution, the laws of the United States. . ." Defendant asks, if all the Supreme Courts over 140 years are unanimous in the opinion that jurisdiction has to be specifically stated in writing, why should that policy be different today? The obvious answer is that the subject of jurisdiction is the same today as it was upon our nation’s founding. Jurisdiction once challenged cannot be assumed to exist, but must be proved (Hagans V. Lavine, 415 US 533 n. 5; Monell V. N.Y. 435 US at 633; U.S. v. More, 3 Cr. 159, 172), the burden of proof being upon the person (e.g. USA) asserting the jurisdiction. (McNutt v. GMAC, 298 U.S. 178; Thomson v Gaskeil, 83 LEd 111, Basso V. UP, 495 F2d 906; Rosemound V. Lambert, 469, F2d 416; Griffin V. Matt., 310 F. Supp. 341, affd. 432 F2d 272. Jurisdiction can be challenged at any time (Brady V. Richardson, 18 Ind. 1; Bia lack V. Harsh, USCA 1972, USS Ct. 1973), all acts of such a forum or court in WANT of jurisdiction being completely void and not just voidable (Sandes V. Sheriff, 200 NYS 9;) POINT V - IS THE SIXTEENTH AMENDMENT LEGAL? 10 Since our Federal income taxes are dependent upon the Sixteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, the question naturally arises "Is The Sixteenth Amendment legal?" To answer this, it is necessary to look and see if it was properly ratified by three fourths of the State legislatures (Article V, U.S. Const.). We supposedly had 48 States in 1913, when the Sixteenth Amendment was submitted for ratification. ¾ of 48 is 36, so we needed ratification from 36 states to make the Sixteenth Amendment a part of the U.S. Constitution. Exactly 36 supposed states including Ohio, ratified the Sixteenth Amendment and it soon thereafter became law. If we only had 47 states, 36 would still be required for ratification as three fourths of 47 is 35.25, and since, it is greater than 35, 36 states were necessary. Proof that Ohio was not admitted as a State into the Union in 1803 by the U.S. Congress is borne by the fact that Congress, in 1953 made a belated attempt to remedy this problem. They passed Public Law 204 which reads as follows: Public Law Chapter 337 Joint Resolution For admitting the State of Ohio into the Union Whereas, in pursuance of an act of Congress, passed on the thirtieth day of April, one thousand eight hundred and two, entitled "An Act to enable the people of the Eastern division of the territory northwest of the river Ohio to form a constitution and state government, and for the admission of such state into the Union, on an equal footing with the original States, and for other purposes", the people of the said territory did, on the twenty-ninth day of November, one thou-sand eight hundred and two, by a convention called for that purpose, form for themselves a constitution and state government, which constitution and state government, so formed is republican, and in conformity to the principles of the articles of compact between the original states and the people and states in the territory northwest of the river Ohio, passed on the thirteenth day of July, one thousand seven hundred and eighty seven: Therefore be it Resolved by the Senate and House of Representatives of the United States of America in Congress assembled, That the State of Ohio, shall be one, and is hereby declared to be one, of the United States 11 of America, and is admitted into the Union on an equal footing with the original States, in all respects whatever. Sec. 2. This joint resolution shall take effect as of March 1, 1803. Approved August 7, 1953. There you have it. Ohio was not a State in 1913, therefore it could not have properly ratified the 16th Amendment. In view of this no basis of lawful authority for Title 26 U.S.- (IRS) Code exists. Accordingly, under Marbury v. Madison, 5 U.S. (2 Cranch) 137, 176, (1803). "All laws (Rules and Practices) which are repugnant to the Constitution are null and void. No parts of the IRS Code or IRS Regulations are admissible as the law of the land. William Howard Taft, U. S. Chief Justice of the Supreme Court, Judge and 27th President of the U.S. was not a citizen or a resident of the U.S. fourteen years prior to his election as an Ohioan, and his presidency from March 4, 1909 to March 3, 1913, was illegal and he was illegally in office. All orders and acts by him as president and judge were illegal, null and void. His decisions as a Supreme Court Judge were improper and illegal and all cases tried by him as a judge were nugatory. Even more surprising, since Taft was never legally president, James S. Sherman, a lawful citizen of the U.S., when sworn in as Vice President, was automatically elevated to President under Article II, Sec. I, Cl. 5 of the Constitution which speaks of the President and says: "In case of. . .inability to discharge the powers and duties of the said office, the same. shall devolve on the Vice President…" Accordingly, on July 31, 1909, when Sherman, who was actually our President, but acting as Vice President, gaveled the U. S. Senate into session for consideration of the Resolution to submit the 16th Amendment to the States for ratification, such acts were illegal because legally he was not authorized by the Constitution to exercise legislative power of any kind. Since he illegally convened the Senate, it was not in session and all acts performed by it were and are non-existent. Therefore, the 16th Amendment was never submitted to the States for ratification. The Constitution authorized the Vice-President to exercise such power and to vote to break a tie, (Article I, Sec. 3, Cl. 4). They did not authorize such actions by the President in our Constitution, so the Senate was unlawfully convened. Since all acts of Taft were illegal, his appointment of Philander C. Knox, as Secretary of State was illegal. On Feb.25, 1913, Taft’s Secretary of State certified the 16th Amendment as "Valid," and since this was an illegal appointment, so the certification was invalid, null and void. Since the certification was invalid, the 16th Amendment has never been certified according to law. Although in 1953 the U.S. Congress indicated in Public Law 24 that Ohio was in 1802 by their Constitution established as a republican form of government, this is untrue. Art. IV Sec. 4 of the U.S. Constitution guarantees a republican form of government to every State of the U.S. and no state may be admitted whose government is not 12 republican in form. There is no way the Act of 1935 by our Congress could be retroactive to 1803 since Ohio was not then and still is not a republic. In a republican form of government, all authority is in the people but there is no record to show that the Ohio Constitution was ever submitted to and ratified by the people of Ohio. Since the Constitution was never approved and ratified by the people of Ohio, Ohio is still a free and independent sovereign state and NOT A MEMBER STATE OF THE U.S. There are those who maintain the 16th Amendment to the constitution, commonly known as the income tax law, was never properly ratified. The courts have completely ignored these claims. Recently, new information has come to light which would seem to indicate that the 16th Amendment cannot be valid law due to the fact that it was not signed by the President of .the United States. The following was entered into the record by Philander C. Knox, Secretary of State of the United States on February 25, 1913: "To all to Whom these Present may come, Greeting" Know ye that, the Congress of the United States at the first Session, sixty-first Congress in the year 9ne thousand nine hundred and nine, passed a Resolution in the words and figures following" to wit-JOINT RESOLUTION Proposing an amendment to the Constitution of the United States Resolved by the Senate and House of Representatives of the United States of America in Congress assembled (two-thirds of each House concurring therein), That the following article is proposed as an amendment to the Constitution of the United States which when ratified by the legislature of three-fourths of the several states, shall be valid to all intents and purposes as a part of the Constitution: Article XVI. The Congress shall have power to lay and collect taxes on Incomes, from whatever source derived, without apportionment among the several states, and without regard to any census of enumeration." In order for a joint resolution to be valid law it must be signed by the President of the United States. The following is from the Library of Congress. "The Statutes at Large of the United States of America:-from March, 1911 to March, 1913 13 Concurrent resolutions of the Two Houses of Congress and recent treaties, conventions and executive proclamations edited and printed and publicized by authority of Congress under the direction of the Secretary of State, Volume 37, part 2, Private Acts and Resolutions, concurrent resolutions, treaties and proclamations. "Private Laws of the United States of America passed by the 62nd Congress 1911 to 1913,Sixteenth Amendment to the Constitution" The Sixteenth Amendment is listed according to this information as both a joint Resolution and as a Private Law. This is very significant when this is analyzed in the light of the intent of the framers of the Sixteenth Amendment. According to Black’s Law Dictionary the definition of a Private Law is as follows: PRIVATE LAW. As used as contradistinction to public law, the term means all that part of the law is administered between citizen and citizen, or which is concerned with the definition, regulation, and enforcement of rights in cases where both the person in whom the right inheres and the person upon whom the obligation is incident are private individuals. Again, according the Black’s Law dictionary the definition of Public Law is as follows: PUBLIC LAW. That branch or department of law which is concerned with the state in its political or sovereign capacity, including constitutional and administrative law, and with the definition, regulation and enforcement of rights in cases where the state is regarded as the subject of the right or object of the duty, including criminal law and criminal procedure, and the law of the state, considered in its quasi private personality, i.e. as capable of holding or exercising rights, or acquiring and dealing with property, in the character of an individual. Holl. Jur. 106,300. That portion of law which is concerned with political conditions; that is to say, with the powers, rights, duties, capacities, and incapacities which are peculiar to political superiors, supreme and subordinate. Aust. Jur. In one sense, a law or statute that applies to the people generally of the nation or state adopting or enacting it, as denominated a public law, as contradistinguished from a private law affecting only an individual or a small number of persons. Morgan V. Cree, 46 Vt. 773, 14 AM. Rep. 640. Scudder us. Smith, 331 Pa. 165, 200 A. 601, 604 goes on to draw the distinction between a Resolution and a Law. The former is used whenever the legislative body passing it wishes merely to express an opinion as to some given matter or thing and is only to have temporary effect on such particular thing, whereas, a law is intended to permanently direct and control matters applying to persons or things in general, from Ex Parte Hague 104 .J. Eq. 31, 144 A, 546, 559. Again, according to Black’s Law dictionary here is the definition of: 14 JOINT RESOLUTION. A resolution adopted by both Houses of Congress or a legislature when such a resolution has been approved by the President or passed with his approval. It has the effect of law. The distinction between a Joint Resolution and a concurrent resolution of Congress is that the former requires the approval of the President while the latter does not. Rep. Sen. Jud. Corn. Jan. 1897. Isn’t this interesting that the 16th Amendment is designated as a Joint Resolution which in order to become law must be signed by the President. The 16th Amendment was not signed by the President of the United States, William Howard Taft, but was signed by the Vice President, who was John Sherman, and it is under the heading of Private Laws of the United States of America and therefore could not be construed to be a Public Law and affects only individuals or small groups of "persons The intent of the framers of the 16th Amendment, which is sup-ported by any number of Supreme Court decisions, was that the income tax was an excise and must be limited to an indirect tax which was assessed on corporations in return for the privilege of doing business in a corporate capacity. Is this the reason the 16th Amendment was designated as a Private Law rather than a Public Law? Again, according to Black’s Law dictionary, we must distinguish between a Private Statute and a Public Statute PRIVATE STATUTE. A Statute which operates only upon particular persons, and private concerns. 1 Bl. Comm. 86. An Act which relates to certain individuals, or to particular classes of men. Swar. St. 629; State V. Chambers, 93 N.C. 600. PUBLIC STATUTE. A statute enacting a universal rule which regards the whole community, as distinguished from one which concerns only particular individuals and affects only their private rights. See Code Civ. Proc. Cal. 1898. Could the reference to particular classes of men refer to corporations? According to the Archives of Congress, the 16th Amendment only bears the signature of the Speaker of the House and the President of the Senate. A concurrent or joint resolution of legislature is not a "law" Koenig v. Flynn, 179 N.E. 705, 707, 258 N.Y. 292; Ex Parte Hague, 105 N.J. Eq. 134, 147 A. 220, 222; Ward V. State, 176 Ok. 386, 56 P.2d 136, 137; Scudder V. Smith, 331 Pa. 165, 200 A. 601, 604; a resolution of the house of representatives is not a "law" State ex rel. Todd V. Yelle. 7 Wash 2d 443, 110 P 2d 162, 165: An unconstitutional statute is not a "law, John F. Jelke Co. V. Hill, 208 Wis. 650, 242 N.W. 576, 581: 4 15 Flournoy V. First Nat. Bank of Shreveport, 197 La. 1067, 3 So. 2d 244, 248. When a statute is passed in violation of law, that is, of the fundamental law or constitution of a state, it is the prerogative of the courts to declare it void, or, in other words, to declare it not to be law. Burrill This court is obligated to recognize the rights of the individual in income tax matters as well as the law not to mention the oath of office it solemnly took to uphold and defend the Constitution of the United States. CONCLUSIVELY: Jurisdiction must be specifically granted in writing to a specific court by Congress before any court has jurisdiction.. Congress is incapable of granting criminal jurisdiction over cases that are supported by civil codes to any court whatsoever. Therefore, the Federal District Courts do not have jurisdiction over Defendant in the subject case. Because of the reasons cited by Defendant, Defendant’s Motion should be granted. 16 Part II Use of Special Appearances The Special Appearance In propria persona – not even pro se but in the proper person The most important pleading that a defendant files in either a civil or a criminal case is "The Special Appearance," which I file in every case, no matter whether there is jurisdiction over the subject matter, and over the person of the defendant, or not. Filing a "Special Appearance" as the first document in any action is the smartest thing a defendant can do. It must be filed, prior to any answer filed, or plea entered. If not it is presumed to have been waived, and can not be raised at another time. By not filing a "Special Appearance," you have waived forever any question as to jurisdiction over the subject matter, and over yourself. I have even filed a "Special Appearance and a General Denial" answer in even the most simple cases, where there is no doubt that the court has personal and subject matter jurisdiction and I have ~fl the case based upon the filing of a "Special Appearance. Many courts are clogged and often 5 or 6 trials are scheduled for the same day, where there are only 3 judges, and three courtrooms. The clerk hopes that 2 or 3 cases will settle, or the defendant will "cop out" to a lesser plea. But what happens when the cases Involve: #1. Drunken driving with vehicular manslaughter #2. Drunken driving with 2 or more prior convictions for drunken driving #3. Drunken driving with a serious accident, and assault of an officer? These three cases will go to trial, since all three defendants are looking at certain jail time (usually compelled by law) and the prosecution can not make a plea bargain granting probation. The judge then looks at my case, and notices that I’ve filed a Special Appearance contesting jurisdiction. He wants to dismiss the case because there are not enough judges, or courtrooms available, but he can’t dismiss a drunk driving case without Mothers’ Against Drunk Driving, getting on his case. By my filing a "Special Appearance beginning" of this case, before any plea was entered, I’ve given the Judge an easy out. He merely tells the prosecutor that there are problems concerning jurisdiction, and that he’s going to dismiss the case because of the apparent jurisdictional problems. This still makes the Judge tough on drunk drivers, and gets the support of M.A.D.D. comes re-election time, and of course, the prosecutor has authority to go along with 17 a dismissal for jurisdictional reasons, wherein most do not have the authority to dismiss a drunk driving case on the merits of the case. This may sound confusing, but that’s the way the system works. The smart defendant gives the Judge an out. He won’t always take it but even If you lose, and appeal, it gives the prosecutor an out to dismiss, somewhere along the line, since when an appeal is filed, he then must work the next three or four weekends, putting together a brief. Remember, he’s a civil servant, and doesn’t get overtime for briefing cases on the weekends. Briefs have very severe time limitations, and if it’s not filed on time, you lose. Most law books will tell you that you should choose between subject matter jurisdiction, and personal jurisdiction. This is hog wash. Always allege that the court has absolutely no jurisdiction over the subject matter and over your person. You don’t have to prove anything, and once you’ve alleged it, it can be brought up again at any time during the trial, appeal, or post conviction hearings. An example that best typifies how this works was a drunk driving case I was defending, wherein I filed a "Special Appearance" and demanded a jury trial. I had no argument that I could think of regarding jurisdiction in this case. When we went into the judge’s chambers,’ prior to picking the jury, the judge started talking about my Special Appearance, and wanted to know what proof I had. I told him that I would call witnesses at trial to prove the jurisdiction defects of the case. The judge then said, “This case involves a driver; the defendant driving his car in a westerly direction on Larpenteur Avenue at a high speed, and in a weaving manner. The City of St. Paul’s northern boundary is the middle of the street of Larpenteur Avenue. Since the defendant was going West, he was over the line and was officially in Roseville, when he was stopped by the cop. Therefore, the St. Paul police were out of their jurisdiction when they arrested him." WOW!!! I couldn’t believe it. My client had won, and because we were in chambers, and he wasn’t present, he thought I was the smartest lawyer in the world. He figured he’d have to pay a fine of $1.000.Oo and have his license suspended for 90 days, and have to buy assigned risk insurance for the next 5 years. I’d saved him over $7,000.00, and when I filed the Special Appearance, I had no idea about the boundaries of St. Paul and Roseville. Irwin Schiff would have won his "willful failure to file income taxes" case had he filed a one page document called, "Special Appearance." In a big case, the defendant should always ask for 10 days to file a brief on the law, regarding jurisdiction, and I don’t know of any case, where the judge denied the request. Remember, failure to raise the defense of "no jurisdiction" waives It forever. If you want a copy of the law regarding "Special Appearances" and a copy of the "Special Appearance" I use, and a copy of an "Answer" that includes a "Special Appearance," write me at: William Drexler, 3368 Governor Drive #186, San Diego, CA 92122 18 Tel: (619) 458 5984 and enclose a self-addressed, stamped envelope (2 stamps), along with 5 F.R.A.U.D.S. Enclose $25.00 more and I’ll send you a tape explaining the proper use, along with the law cases to support it. Note: Many court rules have abolished the Special Appearance. Don’t believe them, always file one anyway, unless of course, you want to become a Kamikaze. Good luck and God bless. Bill Drexler The procedural treatment of subject-matter jurisdiction significantly differs from that of territorial authority to adjudicate and of notice. 1. SUBJECT-MATTER JURISDICTION This requirement is considered so fundamental that its satisfaction is open to question throughout the ordinary course of the initial action. Being courts of limited jurisdiction, the federal courts apply this requirement somewhat more strictly than do most state courts. See generally Wright’s Hornbook ##7, 69; Judgments Second # 11 comment d. a. Pleading The party invoking federal jurisdiction must affirmatively allege the grounds upon which subject-matter jurisdiction depends. See Federal Rule 8(a)(1)(complaint); 28 U.S.C.A. # 1446(a) (notice of removal). If challenged, that party bears the burden of showing that such jurisdiction exists. 19 b. Challenging Any party may challenge federal jurisdiction at any time in the ordinary course of the initial action, and the trial or appellate court should on its own motion dismiss for lack of subject-matter jurisdiction whenever perceived. See Federal Rule 12(h)(3). Thus, even the party who invoked jurisdiction may, on his appeal from a judgment against him, challenge such jurisdiction. 2. TERRITORIAL AUTHORITY TO AUJUDICATE AND NOTICE In the initial action the key for defendant is to raise these personal defenses in a way that avoids waiving them. A - Special Appearance This is the basic technique by which defendant raises these threshold defenses; 1. Availability There are four significant judicial approaches to the availability of a special appearance. a) Appearance Treated as Waiver According to old case law, a state can constituti6nally treat any appearance as waiving these threshold defenses. Thus, defendant would have to choose between (1) appearing in order to defend on the merits and (2) defaulting in order to preserve the important threshold defenses as grounds for relief from judgment. However, today all states have removed this wrenching dilemma by permitting some manner of special appearance. b) Defense on Merits Treated as Waiver Although allowing a special appearance, a few states rule that if the trial judge rejects such challenge, defendant must then choose between (1) defending on the merits and (2) appealing on the basis of those threshold defenses. In other words, these states treat a defense on the merits as a waiver of any right to pursue further those threshold defenses. c) Interlocutory Appeal Allowed Some states mitigate this latter dilemma by permitting defendant to appeal an unsuccessful special appearance before defending on the merits. d) Defense on Merits and Final Appeal Allowed Most states, and the federal courts, permit in effect a special appearance. If that fails, defendant may proceed to defend on the merits. If that too fails, defendant may appeal both on those threshold defenses and on the merits. See Harkness V. Hyde, 98 U.S. 476 (1879) (federal approach). 20 2. PROCEDURE Defendant must be very careful to follow precisely the procedural steps of a special appearance, making immediately clear that she is appearing specially to challenge territorial authority to adjudicate or notice or both, and that she is not appearing generally. The correct steps vary from state to state. See generally Judgments Second #10 comment b. In federal court the "special appearance" is less formalistic, instead coming in the form of a Federal Rule 12(b) defense: (1) Rule 12(b)(2) covers the defense of lack of territorial jurisdiction; (2) Rule 12(b)(3) covers improper venue; (3) Rule 12(b)(4) covers defects in the form of the suin~ns; and (4) Rule 12(b)(5) covers defects in the manner of transmitting notice. Defendant must raise any such available defenses at the very outset, either in a Rule 12(b) motion or in her answer, whichever comes first. With some risk, defendant may first engage in certain preliminary procedural maneuvers, such as moving for an extension of time to respond. But if defendant first does anything more substantive, she waives these threshold defenses. See Rule 12(h)(1). Indeed, even after properly asserting such defenses, defendant may waive them by inconsistent activity, such as asserting a permissive counterclaim. B. CONSEQUENCES OF RAISING If any of these forum-authority defenses is raised in the ordinary course of the initial action, the judge without jury (1) may, on the application of any party, hear and determine the defense in a pretrial proceeding or (2) may choose to defer the issue until trial. See, e.g. Federal Rule 12(d). In the post-trial period, a defense of Jack of subject-matter jurisdiction will be determined whenever raised. After determination of a forum-authority defense, there may arise the question of its res judicata effects. The normal rules of res judicata apply. But there is the important additional question of the effect that a determination rejecting such a defense has on an attack on the resultant judgment, not in the ordinary course of review in the trial and appellate courts but in subsequent litigation. There the principle of finality generally outweighs the concern for validity, giving the determination preclusive effect and thus generating a special variety of res judicata labeled "jurisdiction to determine jurisdiction." 1. Subject-Matter Jurisdiction A finding of the existence of subject-matter jurisdiction precludes the parties from attacking the resultant judgment on that ground in subsequent litigation, except in special circumstances such as where (1) the court plainly lacked subject-matter jurisdiction or (2) the judgment substantially infringes on the 21 authority of another court or agency. See generally Judgments Second #12 comments c, e. C. CONSEQUENCES OF NOT RAISING Consider finally the question of what happens if any of these forum-authority defenses is not raised at all in the ordinary course of the initial action. Here there is a basic distinction between litigated actions and complete defaults. 1. Litigated Action a. Subject-Matter Jurisdiction Because un-raised subject-matter jurisdiction is supposedly always implicitly determined to exist in any action litigated to judgment, such determination has the res judicata consequences of an actually litigated determination of the existence of subject-matter jurisdiction insofar as foreclosing attack on the judgment. However, the court in subsequent litigation may here be more likely to find applicable an exception to res judicata. See generally id. # 12 comment d. b. Territorial Authority to Adjudicate and Notice By failing properly to raise any such threshold defense, an appearing defendant waives it. See, e.g., Federal Rule 12(h)(1). This precludes the appearing parties from attacking the resultant judgment on that ground in subsequent litigation. LOSS OF IMMUNITY FROM SUIT * * * * * Any Judge that acts in any case before him, wherein he does NOT have Jurisdiction, cannot claim judicial immunity and may be sued personally by the injured party. Punitive and/or Exemplary Damages may be awarded on top of General Damages. DO NOT CHANGE THE "SPECIAL APPEARANCE". THIS FORM HAS BEEN USED AND TESTED FOR OVER 30 YEARS, AND IT WORKS. 22 IN THE _______________ COURT, STATE OF _______________ COUNTY OF ______________________ STATE OF _________________ ) CASE # ___________________ PLAINTIFF ) VS ) ) SPECIAL APPEARANCE AND ORDER TO DISMISS WITH __________________________ ) PREJUDICE DEFENDANT ) __________________________ ) COMES NOW _____________________, Defendant, and gives notice to the Hon. Judge _______________, of the ________________ court, that he is denying jurisdiction to this court and to the above named judge. On the _____ day of ______________, 19___, Officer ___________, Badge # ________, District _______, Did stop Defendant without a warrant and issue a citation (invitation)to appear in your court. The Defendant does not wish to accept the Officer's invitation to appear in court to be charged. Jones v. State, 167 N.Y.S. 2d 536, 538; 8 Misc. 2d 140 Traffic infractions are not crimes. People v. Bliss, 278 N.Y.S. 2d 732, 735; 53 Misc. 2d 472 ARREST Whom to be made by: it must be made by an officer having proper authority; this is, in the United States, the Sheriff. Cowp. 65 Arresting officer did not request a personal appearance in court be required on the issued _______________. 23 The Defendant directs this court dismiss the "violation" of _________ Act, State of ___________, Code number _______, for the following reasons: 1. IMPROPER SUMMONS The Writ, SUMMONS, commands the Sheriff or his authorized officials to notify a party to appear in court to answer a complaint made against him specified on a day therein mentioned. 3 Bla. Com. 279 The above named officer is not an authorized officer of the sheriff. The summons is unsigned by an officer of proper jurisdiction. 2. IMPROPER COMPLAINT The allegation (COMPLAINT) must be made TO a proper officer , that some person, whether known or unknown, has been guilty of a designated offence, with an offer to prove the fact, and request that the offender may be punished. To have legal effect, the complaint must be supported by such evidence as shows that an offense has been committed and renders it certain or probable that it was committed by the person named or described in the complaint. COM v. DAVIS, 11 Pick. (Mass) 436 None of the above has been accomplished; therefore the Defendant cannot answer a complaint that has not been made. To make a defense where no allegation or supporting evidence is offered and properly written and filed, and forced to do so, is at least and no less a violation of a citizen's rights, and more specifically protection from being forced to be a witness against oneself, and the Privacy Act. 3. TRAFFIC TICKET INVALID The Traffic Ticket states: The undersigned, being duly sworn, upon his oath deposes and says the following…". The officer was not duly sworn and the complaint was not verified. Therefore, this complaint is null and void, and has no legal binding in this court or in this case. This has been similarly ruled in other courts of law as in HOUSEH v. PEOPLE, Ill. 75-491, PLUMER v. STATE, Ind. 135-308, backed by Federal 34 NE 968, STATE v. GLEASON, 32 Kan. 245, BALARD v. STATE, 43 Ohio 340 24 CONCLUSION: Therefore, this court has no lawful jurisdiction over the above entitled case, and Defendant respectfully moves this court to dismiss the charges against Defendant. Respectfully Submitted, __________________________________ , Pro Per AFFIDAVIT: I, _________________________, being the Defendant in the above mentioned case, do state that the statements and information contained herein are true and correct to the best of my knowledge and belief. __________________________________ , Pro Per Subscribed and affirmed before me, a Notary Public of the State of ___________, County of _______, on this ____ day of ________________, 19___; I herewith set my hand signature and affix my official seal. My commission expires ___________ ______________________________ Notary Public 25 AFFIDAVIT OF DEFENSE This affidavit is not part of the pleadings; It is merely to prevent a summary judgment. MUIR v. INS. CO, 203 Pa. 338, 53 Atl. 158 I, ____________________, The Defendant, do say that the above NOTICE OF SPECIAL APPEARANCE is true to the best of the Defendant's knowledge and belief, and that all facts stated in the SPECIAL APPEARANCE are true. McCARNEY v. McCAMP, 1 Ashm. (pa) 4: By what authority does this court assume to have jurisdiction over the Defendant? Where is the Court's jurisdiction in this case? What type of jurisdiction does this court claim? Where the jurisdiction of a court as to the subject-matter is limited, the consent of the parties cannot enlarge it. FLEISCHMAN v. WALKER, 91 Ill. 319; The test of the jurisdiction of a court is whether or not it had the power to enter upon the inquiry, and not whether its conclusion in the course of it was right or wrong. BOARD OF COM'RS OF LAKE COUNTY v. PLATT, 79 Fed. 567, 25 C.C.A. 87 Act of March 1, 1875 (18 Stst. 336 & 1,2) PROVISION: "All persons within the jurisdiction of the United states shall be entitled to the full and equal enjoyment of the accommodations of inns, public conveyances on land or water, theaters, and other places of public amusement. This shall be subject only to the conditions and limitations established by law, and applicable alike to citizens of every race and color, regardless of previous condition of servitude"…subject to penalty, held not to be supported by the Thirteenth and/or Fourteenth Amendments of the United states constitution, supported as it must in letter and spirit by the state statutes. CIVIL RIGHTS CASES, 109 U.S. 3 (1883), 8 U.S. Justices Concurring, 1 Dissenting. CIVIL DEATH is the state of a person who, though possessing Natural Life, has lost all his civil rights, and as to them, is considered as dead. PLATNER v. SHERWOOD, 6 Johns. Ch. (N.Y.) 118; TROUP v. WOOD, 4 Johns. Ch. (N.Y.) 228, 260 _____________________________________ Defendant Subscribed and affirmed before me, a Notary Public of the State of ___________, County of _______, on this ____ day of ________________, 19___; I herewith set my hand signature and affix my official seal. My commission expires ___________ _________________________________ Notary Public ORDER After reviewing all evidence and facts of the above case presented to this court, this court ORDERS this case to be dismissed with prejudice. _____________________________________ 26 Judge CERTIFICATION OF MAILING This is to certify that the foregoing was duly served by mail upon counsel of record at their address last known, on the _____ day of _______________, 19 __. _____________________________________ (Person other than Defendant) Subscribed and affirmed before me, a Notary Public of the State of ___________, County of _______, on this ____ day of ________________, 19___; I herewith set my hand signature and affix my official seal. My commission expires ___________ _________________________________________ Notary Public 27