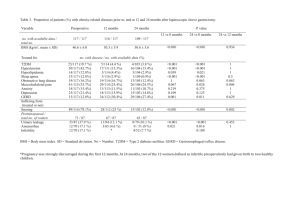

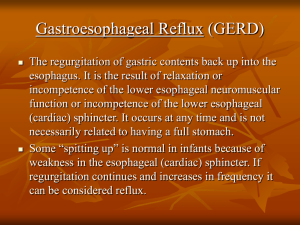

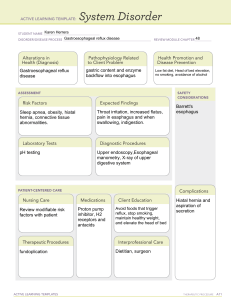

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/51857290 Positive Effect of Abdominal Breathing Exercise on Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease: A Randomized, Controlled Study Article in The American Journal of Gastroenterology · December 2011 DOI: 10.1038/ajg.2011.420 · Source: PubMed CITATIONS READS 72 6,643 9 authors, including: Andreas Eherer Christoph Högenauer Medical University of Graz Medical University of Graz 54 PUBLICATIONS 935 CITATIONS 255 PUBLICATIONS 4,242 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE SEE PROFILE Stefan Scheidl Guenter Krejs Medical University of Graz Medical University of Graz 45 PUBLICATIONS 1,540 CITATIONS 355 PUBLICATIONS 9,438 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE SEE PROFILE Some of the authors of this publication are also working on these related projects: Positive Effect of Abdominal Breathing Exercise on Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease: A Randomized, Controlled Study View project Glycated hemoglobin and variant hemoglobins View project All content following this page was uploaded by Stefan Scheidl on 22 April 2014. The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file. ESOPHAGUS 372 ORIGINAL CONTRIBUTIONS nature publishing group Positive Effect of Abdominal Breathing Exercise on Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease: A Randomized, Controlled Study A.J. Eherer, MD1, F. Netolitzky1, C. Högenauer, MD1, G. Puschnig1, T.A. Hinterleitner, MD1, S. Scheidl, MD2, W. Kraxner, MD1, G.J. Krejs, MD1 and Karl Martin Hoffmann, PD, MD3 OBJECTIVES: The lower esophageal sphincter (LES), surrounded by diaphragmatic muscle, prevents gastroesophageal reflux. When these structures become incompetent, gastric contents may cause gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD). For treatment, lifestyle interventions are always recommended. We hypothesized that by actively training the crura of the diaphragm as part of the LES using breathing training exercises, GERD can be positively influenced. METHODS: A prospective randomized controlled study was performed. Patients with non-erosive GERD or healed esophagitis without large hernia and/or previous surgery were included. Patients were randomized and allocated either to active breathing training program or to a control group. Quality of life (QoL), pH-metry, and on-demand proton pump inhibitor (PPI) usage were assessed at baseline and after 4 weeks of training. For long-term follow-up, all patients were invited to continue active breathing training and were further assessed regarding QoL and PPI usage after 9 months. Paired and unpaired t-test was used for statistical analysis. RESULTS: Nineteen patients with non-erosive GERD or healed esophagitis were randomized into two groups (10 training group and 9 control group). There was no difference in baseline patient characteristics between the groups and all patients finished the study. There was a significant decrease in time with a pH < 4.0 in the training group (9.1±1.3 vs. 4.7±0.9%; P < 0.05), but there was no change in the control group. QoL scores improved significantly in the training group (13.4±1.98 before and 10.8±1.86 after training; P < 0.01), but no changes in QoL were seen in the control group. At longterm follow-up at 9 months, patients who continued breathing exercise (11/19) showed a significant decrease in QoL scores and PPI usage (15.1±2.2 vs. 9.7±1.6; 98±34 vs. 25±12 mg/week, respectively; P < 0.05), whereas patients who did not train had no long-term effect. CONCLUSIONS: We show that actively training the diaphragm by breathing exercise can improve GERD as assessed by pH-metry, QoL scores and PPI usage. This non-pharmacological lifestyle intervention could help to reduce the disease burden of GERD. SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL is linked to the online version of the paper at http://www.nature.com/ajg. Am J Gastroenterol 2012; 107:372–378; doi:10.1038/ajg.2011.420; published online 6 December 2011 INTRODUCTION Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) places an increasing burden on our health-care system. GERD presents with a wide spectrum of symptoms and in less than half of the patients with endoscopically detectable changes at the gastroesophageal junction (1,2). Non-erosive reflux disease (NERD) is as difficult to treat as the ulcero-erosive variant of the disease. When lifestyle modification fails, treatment of GERD is mainly medical, in selected cases surgical. Both approaches are highly effective. Proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) are today’s standard therapy. However, some concern has increasingly been raised about long-term intake of PPIs. Withdrawal of PPIs may be difficult (3). The surgical approach 1 Division of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Department of Internal Medicine, Medical University Graz, Graz, Austria; 2Division of Pulmonary Medicine, Department of Internal Medicine, Medical University Graz, Graz, Austria; 3Division of General Pediatrics, Department of Pediatric and Adolescent Medicine, Medical University Graz, Graz, Austria. Correspondence: Karl Martin Hoffmann, PD, MD, Division of General Pediatrics, Department of Pediatric and Adolescent Medicine, Medical University Graz, A-8036 Graz, Austria. E-mail: hoffmaka@mac.com Received 26 April 2011; accepted 1 September 2011 The American Journal of GASTROENTEROLOGY VOLUME 107 | MARCH 2012 www.amjgastro.com can be accompanied by considerable side effects and endoscopic methods have largely failed to treat GERD (4,5). Lifestyle modifications as supportive measure are always recommended, their mechanisms and effects, however, have not been well studied. Although there is limited data for a positive effect of a change of sleeping position with elevation of the head of the bed and weight loss, there are no or only short-term studies using manometry or pH-metry for most recommended lifestyle changes, such as modification of eating behavior, chewing of gum, and other measures (6). The long-term effect of such measures on the course of the disease is mainly unknown. We wanted to pursue an alternative treatment approach for patients with NERD or healed esophagitis with persistent GERD symptoms by offering a breathing training program in addition to standard acid-suppressive therapy. We chose NERD patients for our study because on-demand PPI therapy is an accepted and recommended approach for these patients (2). For the majority of patients, the pathogenesis of GERD is considered to be an impairment of the closing mechanism of the lower esophageal sphincter (LES). This is due to an increased number of transient LES relaxations and/or low LES pressure. In advanced disease, the LES is destroyed and the tubular part of the esophagus cannot clear refluxed gastric contents (7). The pathophysiology of early stages of the disease, however, is not well characterized, and persons susceptible for GERD have not been carefully investigated. The nature of early events in the pathogenesis of GERD remains to be elucidated. It is believed that synergy of the function of the LES and its surrounding crura of the diaphragm, when superimposed, are of importance for competent closure (8). Even after the surgical removal of the LES, a pressure zone is detectable due to contractions of the crura of the diaphragm (9). Like any other striated muscle of the body, the crura of the dia- phragm should be amenable to improved performance by physical exercise. Our hypothesis is that training of the diaphragm with a breathing exercise could decrease reflux and improve symptoms of GERD. METHODS We included adult (18 years and above) GERD patients using ondemand acid-suppressive therapy. Reflux was proven by a positive pH-metry (see below). Exclusion criteria were hiatal hernia >2 cm, previous operation at the LES, actual erosive esophagitis proven endoscopically, and concomitant conditions preventing patients from training. Erosive esophagitis that was proven to be healed did not constitute an exclusion criterion (see Consort diagram). The study started in November 2004 when consecutive patients attending our gastroenterology clinic were invited to participate. For further recruitment, we advertised the study in a local newspaper, which resulted in calls from some 200 interested persons. If patients could not provide a recent upper gastrointestinal endoscopy report, such a study was done to exclude a large hiatal hernia and erosive disease. Inclusion of patients ended in February 2006, follow-up in December 2006. The study was registered retrospectively with the UMIN Clinical Trials Registry (Registration Number: R000005808). The study design The study design is outlined in Figure 1. Controlled study After endoscopy, a period of at least 4 weeks followed to continue or establish on-demand therapy for GERD symptoms. Endoscopy 4 Weeks On-demand Rx Manometry pH-metry 7 Days PPI and H2 Blocker Randomization QoL scores Drug use assessment 7 Days PPI and H2 Blocker 4 Weeks On-demand Rx and No breathing exercise 7 Days PPI and H2 Blocker QoL scores Drug use assessment After at least 9 months: QoL scores and drug use assessment Long-term follow-up Breathing exercise for both groups and Request to continue this Rx Randomized controlled period 4 Weeks On-demand Rx and Breathing exercise Manometry pH-metry QoL scores Drug use assessment Figure 1. Outlines the study design. PPI, proton pump inhibitor; QoL, quality of life. © 2012 by the American College of Gastroenterology The American Journal of GASTROENTEROLOGY 373 ESOPHAGUS Breathing Exercise and GERD 374 Eherer et al. ESOPHAGUS Table 1. Characteristics of patients perfoming breathing exercises and control group at the time of inclusion in the study Exercise group (n =10) Age 48 ± 4 years ♀: ♂ 5:5 BMI 22.0 ± 1.0 Control group (n =9) n.s. 55 ± 4 years 4:5 n.s. 24.9 ± 0.6 Smoker 1 0 Any lifestyle modification 10 8 Exclusion of certain food 7 3 Elevated bed 4 6 Omitting tight cloths 2 4 Sports 5 8 Duration of symptoms 11.6±1.7 years n.s. 7.4±1.7 years BMI, body mass index; n.s., not significant. Values are expressed as absolute numbers or mean±s.e.m. Patients took their acid-suppressant drugs (PPI, H2 blockers, and antacids) as needed to guarantee their comfort. Patients did not change drug brands during the study. After quality of life (QoL) scores and an assessment of drug usage had been obtained, patients were asked to abstain for 1 week from acid-suppressant therapy except antacids to allow for an accurate pH-metry without influence of medication. pH-metry followed manometry, and when patients showed pathologic reflux on pH-metry they were considered suitable for the study and randomized for either breathing exercise or no breathing exercise. Blocked randomization was performed in blocks of four closed envelopes (two with the training option and two with the control group option) that were brought into random order by a person who had not personally sealed the envelopes and was not involved in study design or treating study patients. The groups of four were then consecutively numbered and used to randomize the study patients. None of the treating physicians were aware of the initial choice of treatment. The randomized controlled study period lasted 4 weeks with or without breathing exercise; all patients were taking on-demand their anti-reflux medication. The groups were not blinded to treatment due to the lack of plausible sham procedures, which possibly also would have influenced the outcome measurements. QoL scores and drug use assessment were again obtained, followed by another week without acid-suppressant drugs to allow for correct pH-metry, preceded by a manometry. Primary outcome was a change in pH-metry after training and secondary outcomes were changes in manometry, QoL, or PPI usage. Long-term follow-up After the study period, patients who had not practiced the breathing exercises underwent the same training program as the former training group. For long-term follow-up, patients in both groups, now having the same treatment, were dismissed and were requested to continue on-demand acid-suppressant therapy as The American Journal of GASTROENTEROLOGY well as breathing exercise. After at least 9 months after dismissal, patients were again contacted to provide further QoL scores, assess their drug usage and to state whether they were still performing the breathing exercises. Manometry Manometry was performed with a standard Dent sleeve catheter (Dentsleeve International, Mississauga, ON, Canada). A slow pull through established lower and upper margins of the LES, and basal pressure of the LES. A 30-min period followed with the sleeve in LES position, the patients on their right side and air inflation through the abdominal port of the manometry tube at a rate of 15 ml/min. The insufflation was intended to trigger transitory LES relaxations, which were judged visually using the criteria of Holloway (10). pH-metry PPIs or other acid-suppressant therapies except antacids were discontinued for 1 week. A standard pH catheter (VersaFlex, Alpine Biomed Medical Devices, CA) was placed 5 cm above the upper margin of the LES. The pH was recorded during normal daily activities for at least 20 h. pH-metry was considered abnormal when the time fraction with pH < 4.0 was >4.5% of the study period (2). Quality of life scores We used two scores to assess QoL. The GERD Health-Related Quality of Life Scale (11) (German translation and validation by Kamolz T) provides 10 questions regarding heartburn symptoms (such as severity and respect to position, daytime or meals), dysphagia, side effects of medication, and satisfaction with current situation and effect of therapy. Every question is graded 0 (no impairment) to 5 (severe impairment); the results are summarized. The Gastrointestinal Quality of Life Index (GIQLI) (12) is a more general index with 36 questions regarding symptoms, emotional, psychological and social situation, and stress under the ongoing therapy. Patients themselves filled in the forms at home without outside help. Help was, however, provided as needed when patients reported to the clinic for the manometry procedure. Breathing exercise The purpose of the training was to induce a change from thoracic to abdominal breathing, which involves diaphragmatic contraction. Abdominal breathing techniques are used by many professional singers as a basic training method. Our program was developed by a professional vocal coach (Professor Karl Ernst Hoffmann, Graz, Austria) and modified by our physiotherapist. Exercises were performed in a standing, sitting, or supine position. Subjects were instructed to practice without exertion or discomfort. The breathing exercises were taught by a professional physiotherapist. Patients had individual one-on-one training for 1 h; follow-up training was continued until patients performed to the physiotherapist’s satisfaction. They were given a booklet with a detailed description of the exercises and as a help for timing, a VOLUME 107 | MARCH 2012 www.amjgastro.com Breathing Exercise and GERD a 375 University of Graz; written informed consent was obtained from all patients. Time fraction pH < 4 25 n.s. 20 P < 0.05 RESULTS After interviews and gastroscopy, 19 patients with established NERD or healed esophagitis agreed to participate and were enrolled in the study and then randomly divided into two groups. Patient characteristics for the two treatment groups are given in Table 1; their mean age and body mass index were not significantly different. Both groups had suffered from GERD for many years. All 19 patients finished the controlled study period. 15 10 5 0 1 Month 1 Month After Before Before Training After Controlled trial No training Mean ± s.e.m. b 30 GERD HRGIQLI in patients with and without exercise n.s. n.s. P < 0.01 GERD HRGIQLI 25 20 15 pH-metry. At baseline, there was no difference in the time fraction of pH < 4.50 (9.1±1.3% vs. 10.7±1.8%) in both groups (Figure 2a). After 1 month, pH-metry showed a significant decrease in acid exposure in patients in the breathing exercise group (4.7±0.9%, P < 0.05; power 0.6). There was no significant change in the control group (9.7±2.1%). Between-group comparisons were not significant. In the training group, four out of nine patients reached normal values of the fraction time with pH < 4, whereas in the non-training group only one subject had normal values. One patient in each group refused follow-up pH-metry because of discomfort. There was no correlation between severity of reflux in pH-metry and GERD symptoms. 10 5 1 Month 0 1 Month After Before Training Before After No training Mean ± s.e.m. Figure 2. pH-metry data and quality of life score. (a) Results of pH-metry given as % time with pH < 4.0 of training and non-training groups before and after the controlled study period are shown. Green circles denote individual patients; red circles with vertical bars denote mean±s.e.m. In each group, one patient refused pH-metry after the study period. (b) Quality of life (QoL) scores specific for gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) (GERD-HRGIQLI) of training and non-training groups before and after the controlled study period are shown. The higher the score, the poorer the quality of life, i.e., a patient with a higher score is worse off. Green circles denote individual patients; red circles with vertical bars denote mean± s.e.m. HRGIQLI, Health-Related Quality of Life Scale. CD covering 30 min with an audio explanation of the exercises and accompanying music. Training then entailed daily practice for at least 30 min. After the first week, a session was again supervised by the physiotherapist. Exercises are described in detail in the Supplementary Appendix. Quality of life. Figure 2b shows that reflux-specific QoL (GERDHealth-Related Quality of Life Scale) did not differ in the two groups at the beginning of the study. QoL scores, however, improved significantly after 1 month of daily training (13.4±1.98 before and 10.8±1.86 after training; P < 0.01; power 0.9), whereas non-training patients showed no change (13.7±2.75 vs. 13.9±2.8). Between-group comparisons were not significant. The more general Eypasch score, focusing more on psychosocial aspects, showed no difference between the groups, before and after treatment (101.5±6.8 before and 110.4±6.5 after training, 99.4±6.2 before and 101.6±7.0 after not training; n.s.). Proton pump inhibitor usage. On-demand use of PPIs showed no difference between the groups after 1 month (107±30 mg PPI/week before and 105±32 mg PPI/week after training, 171±47 before and 140±39 after not training). Manometry. None of the common measurements showed significant changes to explain how breathing exercise could provide a benefit in GERD (Table 2). We found no difference in basal pressure and intra-abdominal and transdiaphragmatic pressure. We found no difference in transient LES relaxations, which were induced by insufflation of air into the stomach for half an hour. Statistics We used the paired and unpaired t-test after checking for normal distribution for in-group and between-group comparisons. No side effects were observed during the study. The study protocol was approved by the ethics committee of the Medical © 2012 by the American College of Gastroenterology Long-term follow-up Quality of life. After the controlled study period, all patients were taught to practice abdominal breathing. Nine months thereafter only 11 out of 19 still continued training (6 of initial The American Journal of GASTROENTEROLOGY ESOPHAGUS n.s. 376 Eherer et al. Training group Basal pressure (mm Hg) Control group Baseline P 4 weeks Baseline P 4 weeks 16±2 n.s. 20±2 13±1 n.s. 16±2 3±1 n.s. 6±2 2±1 n.s. 4±1 75±27 n.s. 129±50 21±8 n.s. 87±40 t-LES relaxations n per 30 min Duration (s) per 30 min LES, lower esophageal sphincter; n.s., not significant. Basal pressure and LES relaxations were measured at baseline and after 4 weeks of breathing training. Numbers are expressed as mean±s.e.m. PPI usage after 9 months 200 symptom scores after 9 months (11.4±2.3 and 13.5±3.3 before and after, respectively). Reasons for the cessation of training were that patients preferred intake of PPIs, that they were too lazy, did not have the time or thought the training was useless. Patients still doing exercises adapted the frequency of training to their individual needs; only six patients kept to a daily time schedule, six performed training 1–2 times per week, and two on demand during heartburn episodes. n.s. PPl mg/week 150 100 Proton pump inhibitor usage. After 9 months still on training PPI usage significantly decreased from 98±34 to 25±12 mg/week (P < 0.05; power 0.6; Figure 3). Patients without long-term training had no PPI usage change (179±31 before to 144±40 after). 50 P < 0.05 0 Start of the study 9 Months DISCUSSION QoL after 9 months 15 GERD HRGIQLI ESOPHAGUS Table 2. Measured values of manometry of training and control group 10 5 0 Start of the study 9 Months Figure 3. Proton pump inhibitor (PPI) usage (denoted as mg/week) and the quality of life (QoL) scores at the beginning of the study and at 9 months of training of patients (both intervention and control group) who were invited to continue abdominal breathing exercises beyond the controlled study period are shown. Filled circles with vertical bars denote mean±s.e.m. GERD, gastroesophageal reflux disease; HRGIQLI, HealthRelated Quality of Life Scale. training group and 5 of initial non-training group). These 11 patients showed a significant and pronounced decrease in their reflux symptom score after 9 months training (15.1±2.2 before to 9.7±1.6 after, P < 0.05; power 0.6; Figure 3). In all, 8 of 19 patients who quit the program had no improvement of reflux The American Journal of GASTROENTEROLOGY Lifestyle modifications, although commonly recommended, lack sufficient data to show objective improvement of reflux (6). A recent position statement paper on the management of GERD reviewed 407 publications on non-pharmacologic therapies (7). This paper concluded that evidence is lacking for the positive effect for most recommended non-pharmacological interventions or lifestyle modifications, such as head of bed elevation, left lateral decubitus position, weight loss, and avoidance of late evening meals (6). However, although weight reduction is considered to be of benefit some controlled studies failed to show a positive effect (13). Nevertheless, many physicians and patients follow these recommendations and experience a subjective advantage. To our knowledge, this is the first controlled study to show that a non-invasive, non-pharmacological intervention significantly improved pH-metry and reflux symptoms of GERD patients. Our intervention was aimed at improving gastroesophageal antireflux mechanisms. It is known that the crural diaphragm has a critical role in this physiological barrier and functions as an extrinsic sphincter in addition to the LES (14). The crural diaphragm is innervated independently as a striated muscle that contracts during inspiration. A breathing technique explicitly involving the diaphragm can be voluntarily trained and is often used by professional singers. This led to our hypothesis that breathing training could train the crural diaphragm, therefore, positively influencing the anti-reflux barrier. This intervention VOLUME 107 | MARCH 2012 www.amjgastro.com showed an improvement in measured acidic reflux, symptoms, and PPI usage; however, significant changes in classical stationary manometry could not be detected. Discrimination of the LES and the crura cannot be accomplished by standard manometry and probably requires special techniques such as pharmacological relaxation of striated muscle under general anesthesia or more advanced manometric techniques such as reversed perfusion sleeve catheter or high-resolution manometry (15,16). We believe that the clinical routine manometric techniques used in our study are too insensitive to discriminate the influence of the crura and to detect this mechanism. This study investigated a subgroup of patients with GERD. They were NERD patients or had endoscopically healed erosive esophagitis with proven pathological acidic reflux (2). All patients with significant anatomical abnormalities were excluded because of the assumption that our intervention would be ineffective in these patients due to a lacking or negative influence of the diaphragmatic crura on the LES. Recommendations regarding breathing exercise for reflux disease can only be made for this subgroup of patients, but not for the whole spectrum of GERD patients. Furthermore, our long-term observation showed that only those patients who were highly motivated and continued to perform the exercises showed long-term benefit. All patients had on-demand PPI therapy for at least 4 weeks before the study intervention started. On-demand therapy was used for the following reasons: First, PPI usage served as an additional parameter for control of GERD. On-demand PPI therapy has been established as an adequate treatment of healed esophagitis and NERD patients (7). Second, the status of the patients was stable before randomization since an on-demand PPI therapy had been applied for 4 weeks. Third, a standardized PPI or other antacid therapy would have resulted in a change of a long-existing therapy in many patients and might have influenced QoL scores before entering the study. A strictly scheduled PPI therapy might have further brought some patients in a symptom-free state of their GERD, making it impossible to assess the effect of breathing exercise on symptoms in these patients. PPI usage decreased to less than one third after 9 months of breathing exercise. This effect was seen in only those patients who voluntarily continued to perform the training in the open labeled extension of the study. This drug usage reduction could result in a substantial economic advantage for our health-care system. Because abdominal breathing exercises likely reduce PPI consumption, this non-pharmacological intervention could be considered in patients who are concerned about long-term drug use and its complications (3). Moreover, the measure is free of side effects except that it takes more time than swallowing a pill. Interestingly, some patients who had improvement of QoL using breathing exercise discontinued their training. On the other hand, some of our patients chose not to increase their ondemand PPI dosage to be symptom free. Both of these observations show that some patients do not utilize the whole spectrum of the offered treatment and obviously accept some degree of persistent GERD symptoms. This aspect of PPI usage is most likely explained on a psychological level. This may be an expla© 2012 by the American College of Gastroenterology nation why some authors consider NERD to be more difficult to treat than erosive GERD (2). There are several limitations to the way our study was performed: First, our group numbers are small due to strict exclusion criteria. Consequently, in the statistical analysis our study is underpowered and between-group comparisons did not show the significant results as compared with in-group analysis. Second, we could not blind our patients to the intervention and we did not use a sham procedure for the control group. While planning the study we have considered a sham procedure for the control group, however, we were not able to design a sham breathing exercise procedure where we could rule out an influence on the diaphragmatic muscle. Furthermore, sham procedures not related to any breathingrelated exercise would have been implausible for the study patients; the patients were therefore not blinded. Third, the manometric method used in our study was probably not sensitive enough to isolate the crural diaphragmatic contractions. More advanced manometric developments such as high-resolution manometry or reverse perfuse sleeve manometry could possibly reveal the underlying mechanisms. In conclusion, our work showed that a breathing exercise can improve GERD as assessed by QOL score, pH-metry, and PPI usage. With increasing prevalence of GERD, a non-pharmacological intervention like breathing exercises could have an important role in reducing the disease burden of GERD. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS We would like to thank Professor emeritus Karl Ernst Hoffmann for adapting his vocal training techniques for our study. We thank Mag Dr Sonja Pöllabauer for the English translation of the original German exercise text for the appendix of the published paper. Many thanks to Ursula Eherer, MD, for her thoughtful input and countless hours of patience during this study. The assistance and advice of Professor Karl Ernst Hoffmann, Mag. Dr Sonja Pöllabauer, Ursula Eherer, MD are gratefully acknowledged. CONFLICT OF INTEREST Guarantor of the article: A.J. Eherer, MD. Specific author contributions: Designed the study with contribution of Karl Martin Hoffmann, conducted the study, performed pH-metry, manometry, and endoscopy, and wrote the paper: Andreas J. Eherer; contributed to performing the study: Felix Netolizky; adapted breathing exercises for physiotherapy, performed and supervised patient training: Georg Puschnig; performed endoscopy and co-wrote the manuscript: C. Högenauer; co-wrote the manuscript: S. Scheidl, W. Kraxner, and Karl Martin Hoffmann; all authors contributed to interpreting the data. Financial support: None. Potential competing interests: All authors have completed the Unified Competing Interest form at http://www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf and declare: no support from any organization for the submitted work; no financial relationships with any organizations that might have an interest in the submitted work in the previous 3 years; no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work. The American Journal of GASTROENTEROLOGY 377 ESOPHAGUS Breathing Exercise and GERD 378 Eherer et al. Study Highlights ESOPHAGUS WHAT IS CURRENT KNOWLEDGE 3Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) places an increasing burden on our health-care system. 3Treatment options include medication, surgery, or lifestyle changing recommendations, which, however, often lack evidence. 3Part of the lower esophageal sphincter (LES) consists of the diaphragmatic crurae, which should be actively trainable. WHAT IS NEW HERE 3We use unique abdominal breathing exercises intended to train the lower esophageal sphincter (LES) crura of the diaphragm in gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) patients. 3These breathing exercises lead to significant improvement of pH-metry and quality of life (QoL) in GERD patients. 3On long-term follow-up, this intervention leads to a significant reduction in proton pump inhibitor (PPI) usage. 3This non-pharmacological intervention could help to reduce the disease burden of GERD. REFERENCES 1. Kahrilas PJ. Clinical practice. Gastroesophageal reflux disease. N Engl J Med 2008;359:1700–7. 2. Modlin IM, Hunt RH, Malfertheiner P et al. Diagnosis and management of non-erosive reflux disease—the Vevey NERD Consensus Group. Digestion 2009;80:74–88. 3. Jensen RT. Consequences of long-term proton pump blockade: insights from studies of patients with gastrinomas. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol 2006;98:4–19. The American Journal of GASTROENTEROLOGY View publication stats 4. Spechler SJ. Medical or invasive therapy for GERD: an acidulous analysis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2003;1:81–8. 5. Chen D, Barber C, McLoughlin P et al. Systematic review of endoscopic treatments for gastro-oesophageal reflux disease. Br J Surg 2009;96: 128–36. 6. Kaltenbach T, Crockett S, Gerson LB. Are lifestyle measures effective in patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease? An evidence-based approach. Arch Intern Med 2006;166:965–71. 7. Kahrilas PJ, Shaheen NJ, Vaezi MF et al. American Gastroenterological Association Medical Position Statement on the management of gastroesophageal reflux disease. Gastroenterology 2008;135:1383–91, 1391.e1–5. 8. Mittal RK, Balaban DH. The esophagogastric junction. N Engl J Med 1997;336:924–32. 9. Klein WA, Parkman HP, Dempsey DT et al. Sphincterlike thoracoabdominal high pressure zone after esophagogastrectomy. Gastroenterology 1993;105:1362–9. 10. Holloway RH, Penagini R, Ireland AC. Criteria for objective definition of transient lower esophageal sphincter relaxation. Am J Physiol 1995;268 (1 Pt 1): G128–33. 11. Velanovich V. The development of the GERD-HRQL symptom severity instrument. Dis Esophagus 2007;20:130–4. 12. Eypasch E, Williams JI, Wood-Dauphinee S et al. Gastrointestinal Quality of Life Index: development, validation and application of a new instrument. Br J Surg 1995;82:216–22. 13. Kjellin A, Ramel S, Rossner S et al. Gastroesophageal reflux in obese patients is not reduced by weight reduction. Scand J Gastroenterol 1996;31:1047–51. 14. Pandolfino JE, Kwiatek MA, Kahrilas PJ. The pathophysiologic basis for epidemiologic trends in gastroesophageal reflux disease. Gastroenterol Clin North Am 2008;37:827–43, viii. 15. Brasseur JG, Ulerich R, Dai Q et al. Pharmacological dissection of the human gastro-oesophageal segment into three sphincteric components. J Physiol 2007;580 (Pt. 3): 961–75. 16. Miller L, Dai Q, Vegesna A et al. A missing sphincteric component of the gastro-oesophageal junction in patients with GORD. Neurogastroenterol Motil 2009;21:813–e52. VOLUME 107 | MARCH 2012 www.amjgastro.com