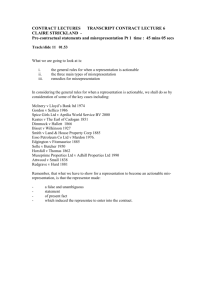

[Catherine Elliott, Frances Quinn] Contract Law(Bookos.org)

advertisement

![[Catherine Elliott, Frances Quinn] Contract Law(Bookos.org)](http://s2.studylib.net/store/data/025724409_1-4c3b4fb251a929c0c06dc6c64581e6c4-768x994.png)