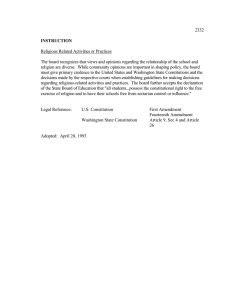

Constitutional Law Selected Terms and Cases 1. judicial review- review by the supreme court on the constitutional validity of a legislative act i. power of courts to invalidate or refuse to enforce statutes, treaties, or executive orders on the ground that they violate or are unauthorized by con law of political system. ii. established in Marbury V. Madison 1803 2. judicial activism/judicial restrainta. judicial activism: a philosophy of judicial decision making whereby judges allow their personal beliefs on subjects of public policy to guide their decision making process. b. judicial restraint refers to a form of judicial interpretation that emphasizes limited nature of the court’s power. It calls for judges to make judicial decisions based on the concept of stare decisis or the court’s obligation to honor previous decisions. Often times, conservative judges will employ judicial restraint. It seeks to limit the power of judges to create new laws and policy. 3. jurisdiction- a court’s legal authority to hear and determine cases in a particular geographic area. For example, the federal government is a jurisdiction unto itself. Its power spans the entire United States. i. One of the most fundamental questions of law is whether a given court has jurisdiction to preside over a given case. A jurisdictional question may be broken down into three components: 1. whether there is jurisdiction over the person (in personam), 2. whether there is jurisdiction over the subject matter, or res (in rem), and 3. whether there is jurisdiction to render the particular judgment sought. The term jurisdiction is really synonymous with the word "power". Any court possesses jurisdiction over matters only to the extent granted to it by the Constitution, or legislation of the sovereignty on behalf of which it functions. The question of whether a given court has the power to determine a jurisdictional question is itself a jurisdictional question. Such a legal question is referred to as "jurisdiction to determine jurisdiction." where did the breach/conflict/argument occur and whether there is a federal question involved. 4. constitutional interpretation- The intellectual activity of search for the true meaning behind the literal words of the Constitution of the United States. 5. intention of the founders- also referred to as originalism or founders intent. a way of interpreting the constitution in a way that is consistent with the founders’ wishes in 1776. 6. plain meaning: also known as the “literal rule” , it is a type of statutory construction which dictates that statutes are to be interpreted using the ordinary meaning of the language of the statute. In other words, the law is to be read word for word and the reading of said law should not be diverted from the intent of the original meaning. 7. narrow constitutional interpretation- interpreting the Constitution based on a literal and strict definition of the language without references to the differences in conditions when the constitution was originally written and the conditions of today’s modern societal changes. 8. broad constitutional interpretation- -- the spirit of the times and needs of the nation may impact judicial interpretation. interpreting the Constitution based on the judges belief of what the framers intended the language to mean. It involves much more interpretation than narrow construction, and aims to expand and Constitutional Law Selected Terms and Cases interpret language to meet current standards of human conduct and complexity of society. 9. federal statutory interpretation- the intellectual activity of search for the true meaning behind federal laws passed by national Congress. 10. state statutory interpretation- the intellectual activity of search for the true meaning behind state laws passed by state legislatures. 11. appellate jurisdiction: The jurisdiction in which a superior court has to bear appeals of causes which have been tried in original courts. 12. original jurisdiction- the authority of a court to hold a trial in the first stance of judgement. 13. petition for certiorari- is an extremely prerogative writ granted in cases that otherwise would not be entitled to review. This is the appeals process the Supreme Court uses to judge its cases, as cases are moved up the judicial latter by way of being reviewed by lower courts then appealing to higher courts by way of petition for certiorari. a. A petition that asks an appellate court to grant a writ of certiorari. This type of petition usually argues that a lower court has incorrectly decided an important question of law, and that the mistake should be fixed to prevent confusion in simi lar cases. 14. plaintiff- the person / party bringing a suit to court and seeking damages 15. defendant- the party being charged for violating some law / regulation 16. appellant- A person who applies to a higher court for a reversal of the decision of a lower court. 17. appellee- The respondent in a case appealed to a higher court. 18. Supremacy Clause: Article IV, section 2 of the United States Constitution is known as the Supremacy Clause because it provides that “The Constitution and laws of The United States shall be the supreme law of the land”. The Federal Government, in exercising any of the powers enumerated in the Constitution, must prevail over any conflicting or inconsistent state exercising of power. 19. the interstate commerce power: Article 1, Section 8 of the United States Constitution empowers the national Congress to “regulate commerce with foreign nations, and among the several states and with Indian Tribes”. The term commerce as used in the Constitution means business or commercial exchanges in any and all of its forms between citizens of different states, including purely social communications of citizens by telegraph, telephone and radio. The mere passage of persons from one state to another for business of pleasure is included under the umbrella of commerce. 20. necessary and proper power: The Necessary and proper clause allows Congress to “make all laws which shall be necessary and proper for carrying into execution the enumerated powers and all other powers vested in this constitution in the Government of The United States or in any Department thereof”. It is found in Article 1, section 8, Clause 18 of the United States Constitution. The necessary and proper clause is also called the “elastic clause”, as powers drawn from the necessary and proper clause may not explicitly be in the text of the Constitution. These powers are often called implied powers. 21. dual federalism- the federal system under which the national and state governments are responsible for Constitutional Law Selected Terms and Cases separate policy areas. 22. marble-cake federalism- the federal system of government in which the national, state, and local governments work together cooperatively thus blurring the lines where one body’s power ends and another’s begins. 23. concurrent power- are powers that are both held by state and federal governments and may be exercised simultaneously within the same territory and to the same body of citizens. Some concurrent powers enjoyed by the government include the power to tax, make roads, protect the environment, create lower courts and borrow money. 24. exclusive power- powers that are held by only one facet of the government be that at the State, Local or Federal level. Only one facet of government can legally apply this power, for example the Federal Government’s ability to tax commerce between several States. 25. Truncation of Commerce: production/shipment/distri-bution 26. laissez faire: an economic doctrine that opposes government regulation or “interference” in commerce beyond the minimum necessary for a free-enterprise system to operate according to its own economic law. 27. Section 10 [of Art. I] limitations on state power: States are prohibited from coining money or making anything other than gold or silver legal tender for payments of debts and are prohibited from entering into treaties or alliances, although compacts with other states are allowed with permission from congress. States are not permitted to law duties, keep troops or warships during peacetime without Congressional approval, or engage in war unless in immediate danger. States are also barred from laying imposts or duties on imports or exports except for the fulfillment of state inspection laws, which may be revised by congress, and any net revenue of such duties is remitted to the federal treasury. States, like Congress, may not pass bills of attainder or ex post facto laws nor grant any title of nobility. 28. Bill of Rights- first ten amendments of the constitution. a summary of citizen rights guaranteed and protected by a govt; added to the constitution as its first ten amendments to achieve ratification 29. The Tenth Amendment/the police power-the powers not delegated to the United States by the Constitution, nor prohibited by it to the states, are reserved to the states respectively, or to the people. 30. The Fourteenth Amendment- Section 1. All persons born or naturalized in the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States and of the state wherein they reside. No state shall make or enforce any law which shall abridge the privileges or immunities of citizens of the United States; nor shall any state deprive any person of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law; nor deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws. ○ Section 2. Representatives shall be apportioned among the several states according to their respective numbers, counting the whole number of persons in each state, excluding Indians not taxed. But when the right to vote at any election for the choice of electors for President and Vice President of the United States, Representatives in Congress, the executive and judicial officers of a state, or the members of the legislature thereof, is denied to any of the male inhabitants of such state, being twenty-one years of age, and citizens of the United States, or in any way abridged, except for participation in rebellion, or other crime, the basis of representation therein shall be reduced in the proportion which the number of such male citizens shall bear to the whole number of male citizens twenty-one years of age in such state. ○ Section 3. No person shall be a Senator or Representative in Congress, or elector of President and Vice President, or hold any office, civil or military, under the United States, or under any state, who, Constitutional Law Selected Terms and Cases ○ ○ having previously taken an oath, as a member of Congress, or as an officer of the United States, or as a member of any state legislature, or as an executive or judicial officer of any state, to support the Constitution of the United States, shall have engaged in insurrection or rebellion against the same, or given aid or comfort to the enemies thereof. But Congress may by a vote of two-thirds of each House, remove such disability. Section 4. The validity of the public debt of the United States, authorized by law, including debts incurred for payment of pensions and bounties for services in suppressing insurrection or rebellion, shall not be questioned. But neither the United States nor any state shall assume or pay any debt or obligation incurred in aid of insurrection or rebellion against the United States, or any claim for the loss or emancipation of any slave; but all such debts, obligations and claims shall be held illegal and void. Section 5. The Congress shall have power to enforce, by appropriate legislation, the provisions of this article. 31. due process of law clause: the Due process of law clause appears in both the Fifth and Fourteenth Amendments of the Constitution. The Fifth Amendment states, “[N]or shall any person . . . be deprived of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law . . .” The Fourteenth Amendment states, “[N]or shall any State deprive any person of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law . . . “ It is an idea taken almost directly from the Magna Carta. “No free man shall be seized or imprisoned, or stripped of his rights or possessions, or outlawed or exiled, or deprived of his standing in any other way, nor will we proceed with force against him, or send others to do so, except by the lawful judgment of his equals or by the law of the land.” While it appears in both the Fifth and Fourteenth Amendments, they are pretty much one in the same. 32. procedural due process- as with substantive due process, government action is required for there to be a cause of action. procedural due process cases do not focus on whether a liberty right or an econimc right is at stake. any deprivation of life, liberty, or property will be subjected to the same level of scrutiny... the nature of the right involved does affect the outcome. 33. substantive due process- The words “due process” suggest a concern with procedure, and that is how the Due Process Clause is usually understood. We have just seen, however, that the clause has been taken as a kind of proxy for other rights. In those cases, the rights were actually expressed somewhere in the Constitution, but only as rights against federal (or state) action. What about rights the Constitution does not mention — “unnamed rights,” as Charles Black calls them, like the right to work in an ordinary kind of job, or to marry, or to raise one's children as a parent? The dominant constitutional controversy of the first third of this century, which still echoes in the arguments about abortion and other “privacy” issues like sexual preference, was about an idea called “substantive due process.” The question was whether "due process of law" might put substantive limits on what legislatures could enact, as well as require procedures of judges and administrators. Thus, in 1905, the Supreme Court found unconstitutional a New York law regulating the working hours of bakers, because it thought the public benefit of the law did not justify depriving the bakers of their right to work under whatever terms they liked. For thirty years, conservative judges sometimes used this idea to find legislative judgments about social or economic programs invalid, retarding the emergence of social welfare legislation. In the late 1930's, after years of sharp criticism, the substantive due process approach was repudiated for "economic regulation." Many think the idea is still vital as a barrier to legislation curbing other individual liberties. 34. Court as Superlegislature35. fundamental right: Rights that have their origin in a country’s constitution, or are necessarily implied from a country’s constitution. Constitutional Law Selected Terms and Cases 36. test of reasonableness- “reasonable basis test”: refers to a level of scrutiny applied by courts when deciding cases presenting Constitutional due process or Equal Protection issues regarding the Fifth or Fourteenth amendment. Reasonable basis is the lowest level of scrutiny that a court applies during judicial review. The reasonable basis test determines whether governmental action is a rational means to an end that may be legitimately pursued by the government. Under this standard of review, the legitamate interest does not have to be the government’s actual interest. Rather, if the court can merely hypothesize a “legitimate” interest served by the challenged action, it will stand the reasonable basis test. 37. strict scrutiny/three-prong test- a heightened standard of review used by the Supreme court to assess the constitutionality of laws that limit some freedoms or that make a suspect classification. There are three reasons legislation will be reviewed under the guise of strict scrutiny. 1) On its face, legislation violates text within the Constitution. 2) Legislation attempts to distort or rig the political process. 3) Legislation discriminates against minorities, particularly those who lack sufficient numbers or power to seek redress through the political process. 38. privileges and immunities clause- The Privileges and Immunities Clause (U.S. Constitution, Article IV, Section 2, Clause 1, also known as the Comity Clause) prevents a state from treating citizens of other states in a discriminatory manner, with regard to basic civil rights. The text of the clause reads: “The Citizens of each State shall be entitled to all Privileges and Immunities of Citizens in the several States.” 39. equal protection clause: The Equal Protection Clause, part of the Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution, provides that "no state shall ... deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws".[1] The Equal Protection Clause can be seen as an attempt to secure the promise of the United States' professed commitment to the proposition that "all men are created equal"[2] by empowering the judiciary to enforce that principle against the states. As written it applied only to state governments, but it has since been interpreted to apply to the Federal Government of the United States as well. a. Generally, the question of whether the equal protection clause has been violated arises when a state grants a particular class of individuals the right to engage in an activity yet denies other individuals the same right. There is no clear rule for deciding when a classification is unconstitutional. The Supreme Court has dictated the application of different tests depending on the type of classification and its effect on fundamental rights. Traditionally, the Court finds a state classification constitutional if it has "a rational basis" to a "legitimate state purpose." The Supreme Court, however, has applied more stringent analysis in certain cases. It will "strictly scrutinize" a distinction when it embodies a "suspect classification." In order for a classification to be subject to strict scrutiny, it must be shown that the state law or its administration is meant to discriminate. Usually, if a purpose to discriminate is found the classification will be strictly scrutinized if it is based on race, national origin, or, in some situations, non U.S. citizenship (the suspect classes). In order for a classification to be found permissible under this test it must be proven, by the state, that there is a compelling interest to the law and that the classification is necessary to further that interest. The Court will also apply a strict scrutiny test if the classification interferes with fundamental rights such as first amendment rights, the right to privacy, or the right to travel. The Supreme Court also requires states to show more than a rational basis (though it does not apply the strictly scrutiny test) for classifications based on gender or a child's status as illegitimate. 40. equity powers of court: There is a difference between court acting as a court of law and a court acting as a court of equity (does divorce papers and forces someone to do something). The distinction between financial Constitutional Law Selected Terms and Cases and nonfinancial. Equity courts issue writs of mandamus. They issue something beyond money damages. Writ of mandamus used in Marbury v. Madison. If court has jurisdiction, issuance of injunction poss. a. contains no jury, only a judge, force someone to do something, force someone to not do something, called upon when a contract is broken and the plaintiff cannot gain a substitute to what he or she originally wanted in the broken agreement. . 41. writ of mandamus: A writ of mandamus or mandamus (which means "we command" in Latin), or sometimes mandate, is the name of one of the prerogative writs in the common law, and is "issued by a superior court to compel a lower court or a government officer to perform mandatory or purely ministerial duties correctly. a. Latin for "we command." A writ of mandamus is a court order that requires another court, government official, public body, corporation, or individual to perform a certain act. For example, after a hearing, a court might issue a writ of mandamus forcing a public school to admit certain students on the grounds that the school illegally discriminated against them when it denied them admission. A writ of mandamus is the opposite of an order to cease and desist, or stop doing something (an injunction). Also called a "writ of mandate." 42. injunction- a court order charging a party NOT to do something. Considered the opposite of mandamus. 43. the Marshall Court: (1801-1835)(chief justice) famous cases include Marbury v Madison, McCullugh v Maryland, and Gibbons v Ogden. 44. the Field Court: (1863-1897)(was an associate justice) famous cases include Slaughterhouse cases, Munn v Illinois, and Plessy v Ferguson. 45. the Hughes Court (1910-1916) (was an associate justice) famous cases include Bailey v Alabama. 46. the Roosevelt Court (1933-1945)(was the president of the United States) famous cases include Schecter v United States and West Coast Hotel v Parrish. 47. originalism: In the context of United States constitutional interpretation, originalism is a principle of interpretation that tries to find out the original meaning or intent and not impose new interpretations foreign to the original intention of the authors. It is based on the principle that the judiciary is not supposed to create, amend or repeal laws (which is the realm of the legislative branch) but only to uphold them. The term is a neologism, which is a formalist theory of law and a corollary of textualism. 48. nonoriginalism: A principle of constitutional interpretation that does not necessarily try to find the original meaning of the text being reviewed. Instead, societal changes of the modern era are weighed in determining how the text should be interpreted. 49. interpretivist: one who interprets. Regarding the constitution, this would relate to a judge who derives meaning beyond the words written in the document being reviewed. 50. noninterpretivist: one who does not interpret. Regarding the constitution, this would relate to a judge who reads words in the constitution literally, and aims to maintain the original meaning of the document being reviewed. 51. “The switch in time that saved nine” is the name given to what was perceived as the sudden jurisprudential shift by Associate Justice Owen J. Roberts of the U.S. Supreme Court in West Coast Hotel Constitutional Law Selected Terms and Cases Co. v. Parrish.[1] Conventional historical accounts portrayed the Court's majority opinion as a strategic political move to protect the Court's integrity and independence from President Franklin Roosevelt's court-reform bill (also known as the "court-packing plan"), which would have expanded the size of the bench up to 15 justices.The term itself is a reference to the aphorism "A switch in time saves nine," meaning that preventive maintenance is preferable.[2] 52. Cases: a. Marbury i. · Brief Fact Summary. William Marbury (Marbury) requested the Supreme Court of the United States (Supreme Court) to issue a Writ of Mandamus ordering the President, Thomas Jefferson (Jefferson) to appoint him Justice of the Peace. ii. Synopsis of Rule of Law. The Supreme Court has judicial review over acts of Congress. This power allows the Supreme Court to declare those acts that fall outside the legislature’s enumerated powers unconstitutional. iii. Facts. William Marbury was named Justice of the Peace for the District of Columbia. This appointment was part of a series of last minute appointments by President John Adams (Adams) before the end of his administration. The incoming Jefferson Administration chose not to honor those appointments because formal commissions had not been delivered by the end of Adam’s term. Marbury petitioned the Supreme Court for a Writ of Mandamus ordering his appointment by the Jefferson Administration. iv. Issue. Does Marbury have a right to the appointment he demands? If Marbury has this right, and the right has been violated, do the laws of the United States afford him a remedy? If the law does afford Marbury a remedy, is it a mandamus issuing from the Supreme Court? v. Held. Marbury has a right to resort to the protection of the law and a writ of mandamus is an appropriate action. However, the Supreme Court does not have original jurisdiction over this matter. If a power granted to the President, is intended solely to be used at the will of the President in his own discretion, it is not examinable by the courts. If a specific duty is assigned by law and individual rights depend upon performance of that duty, an individual with vested rights that has been injured may resort to the laws of the country for redress. Marbury’s appointment is a specific duty, not a political question, and therefore may be addressed by the courts. A Writ of Mandamus is a demand from the court to do a particular thing specified within the writ. A mandamus from a court directed at an officer of the government to appoint Marbury would be an appropriate remedy. Congress had attempted to grant the Supreme Court original jurisdiction to issue Writs of Mandamus through a legislative act. The Court determined through Constitutional interpretation that Congress did not have the authority to grant this power and that the Supreme Court held only appellate jurisdiction over this matter. Therefore, the legislative act was overturned as unconstitutional and Marbury must resort first to the lower courts. vi. Discussion. Judicial review is not a power expressly granted to the Supreme Court in the United States Constitution (Constitution). The Supreme Court has determined it has the power to review acts of the other branches of government to determine their constitutionality and to overrule those acts that fall outside of the powers granted within the Constitution. b. McCulloch i. Brief Fact Summary. The state of Maryland enacted a tax that would force the United States Bank in Maryland to pay taxes to the state. McCulloch, a cashier for the Baltimore, Maryland Bank, was sued for not complying with the Maryland state tax. ii. Synopsis of Rule of Law. Congress may enact laws that are necessary and proper to carry out their enumerated powers. The United States Constitution (Constitution) is the Constitutional Law Selected Terms and Cases c. supreme law of the land and state laws cannot interfere with federal laws enacted within the scope of the Constitution. iii. Facts. Congress chartered the Second Bank of the United States. Branches were established in many states, including one in Baltimore, Maryland. In response, the Maryland legislature adopted an Act imposing a tax on all banks in the state not chartered by the state legislature. James McCulloch, a cashier for the Baltimore branch of the United States Bank, was sued for violating this Act. McCulloch admitted he was not complying with the Maryland law. McCulloch lost in the Baltimore County Court and that court’s decision was affirmed by the Maryland Court of Appeals. The case was then taken by writ of error to the United States Supreme Court (Supreme Court). iv. Issue. Does Congress have the authority to establish a Bank of the United States under the Constitution? v. Held. Yes. Judgment reversed. Counsel for the state of Maryland claimed that because the Constitution was enacted by the independent states, it should be exercised in subordination to the states. However, the states ratified the Constitution by a two-thirds vote of their citizens, not by a decision of the state legislature. Therefore, although limited in its powers, the Constitution is supreme over the laws of the states. There is no enumerated power within the Constitution allowing for the creation of a bank. But, Congress is granted the power of making “all laws which shall be necessary and proper for carrying into execution the foregoing powers.” The Supreme Court determines through Constitutional construction that “necessary” is not a limitation, but rather applies to any means with a legitimate end within the scope of the Constitution. Because the Constitution is supreme over state laws, the states cannot apply taxes, which would in effect destroy federal legislative law. Therefore, Maryland’s state tax on the United States Bank is unconstitutional. vi. Discussion. This Supreme Court decision establishes the Constitution as the supreme law of the land, taking precedent over any state law incongruent with it. Gibbons v. Ogden i. Brief Fact Summary: Ogden was given an exclusive license, pursuant to a New York Statute, to run a ferry between New York and New Jersey. Gibbons obtained a license, pursuant to federal law, to run a ferry in New York waters, thus, running in interference with Ogden’s license. Ogden sought an injunction against Gibbons. ii. Ruling: Congress’s power to regulate interstate commerce does not stop at the external boundary line of a State. Congress’ power to regulate within it’s sphere is exclusive. iii. Facts on the Case: The New York legislature enacted a statue granting Fulton and Livingston an exclusive right to operate a steamboat in New York waters. Thereupon, Fulton and Livingston licensed Ogden to operate a ferry between New York and New Jersey. Later, Gibbons began operating a ferry, licensed under a statue enacted by Congress that necessarily entailed Gibbons entering into New York Waters, thereby violating Ogden’s monopoly. Ogden obtained an injunction against Gibbons from a New York court. iv. Issue: Was the New York court’s injunction against Ogden’s license lawful? v. Held:The Court stated that the New York monopoly was invalid under the Supremacy Clause. Gibbons was given a license to move within the New York waterway, i.e to navigate. Article I, Section 8 of the Constitution grants Congress to power to regulate commerce among several states. Contrary to Ogden’s assertion, “commerce” means more than traffic. It also encompasses navigation. The phrase “among the several states” means “intermingled with Constitutional Law Selected Terms and Cases d. e. f. them.” Therefore, Congress’ power to regulate “among the several states” must not stop at the external boundary line of each State. Congress’ power must also extend to each States’ interior. Moreover, the power of Congress to regulate within its proper sphere, e.g. interstate commerce, is exclusive. vi. Discussion: Chief Justice John Marshall in holding is not sayin that commerce that is completely internal and that does not affect other States is subject to regulation by Congress under the Commerce Clause. Hammer v. Dagenheart (1917) i. Fact summary: keating-owen child labor act prohibited the interstate shipment of goods produced by child labor. Reuben Dagenheart’s father sued on behalf of his freedom to allow his 14 year old son to work in a textile mill ii. Constitutional question: Does the congressional act violate the commerce clause, the tenth amendment, or the fifth amendment iii. Held: day spoke for the court majority and found 2 grounds to invalidate the law. production was not commerce, and thus outside the power of congress to regulate. and the regulation of production was reserved tby the tenth amendment to the states. day wrote “powers not expressly delegated to the national government are reserved” t the states and the people.-- DAY revised the constitution slightly and changed the intent of the framers; the tenth amendment does not say “expressly” the framers purposely left the word expressly out of the amendment because they believed they could not possibly specify every power that might be needed in the future to run the govt. Schechter i. Brief Fact Summary. A.L.A. Schechter Poultry Corporation (Petitioners) were convicted in the District Court of the United States for the Eastern District of New York for violating the Live Poultry Code, promulgated under Section:3 of the National Industrial Recovery Act. ii. Synopsis of Rule of Law. Congress is not permitted to abdicate or transfer to others the essential legislative functions with which it is vested by Article I of the Constitution of the United States. iii. Facts. Section:3 of the Act authorized the President to approve “codes of unfair competition” for trades and industries, and a violation of any code provision in any transaction in or affecting interstate or foreign commerce was made a misdemeanor punishable by a fine. The Live Poultry Code was approved by the President on April 13, 1934. Petitioners were convicted in the District Court for violating the Live Poultry Code, and contended that the Code had been adopted pursuant to an unconstitutional delegation by Congress of legislative power. iv. Issue. Did Congress, in authorizing the “codes of unfair competition” establish the standards of legal obligation, thereby performing its essential legislative function? v. Held. No. The code-making authority conferred was an unconstitutional delegation of legislative power. Under Title 1, Section:1 of the Act there was a broad “Declaration of Policy,” and the President’s approval of a code was simply conditioned on his finding that it would “tend to effectuate the policy of this title.” The Act imposed no limitations on the scope of the new laws, and there was a very wide field of legislative possibilities. Dissent. None. Concurrence. The delegated power of legislation was unconfined and vagrant. vi. Discussion. Section:3 of the Act was without precedent in that it supplied no standards for any trade, industry or activity. Instead of prescribing rules of conduct, it authorized the President to make the codes to prescribe them. Congress made an unconstitutional delegation because it vested in the President a clearly legislative function without imposing necessary standards and restrictions. Jones & Laughlin i. Brief Fact Summary. This case challenges the constitutionality of the National Labor Constitutional Law Selected Terms and Cases g. Relations Act of 1935 (the Act) when the Act regulates activity that occurs solely within the boundaries of one state. ii. Synopsis of Rule of Law. Congress has the power to regulate intrastate activities that potentially could have a significant impact on interstate commerce. iii. Facts. This case challenged the constitutionality of the Act. The National Labor Relations Board (NLRB) found that Jones & Laughlin Steel Corp. (Jones & Laughlin) engaged in unfair labor practices by firing employees involved in union activity. Jones & Laughlin failed to comply with an order to end the discriminatory practices. The NLRB sought enforcement of its order in the Court of Appeals. The Court of Appeals found the order was outside of the range of federal power. The matter was appealed to the Supreme Court of the United States (Supreme Court). iv. Issue. Does the federal government have the power to regulate local employment practices in companies whose business effects interstate commerce? v. Held. Yes. Judgment reversed. The Supreme Court found that Jones & Laughlin does significant business outside of the state of Pennsylvania. The majority of its products were sold outside of the state. Congress retains the power to control and regulate interstate commerce. Although the employee discharges may be an intrastate activity, the repercussions from such discharges have the potential to significantly affect interstate commerce. Therefore, Congress has the power of legislation over such activities. vi. Dissent. The employee discharges are too remote from interstate commerce to justify Congressional regulation. vii. Discussion. Congress passed the Act under its commerce power. The commerce power is a broad ranging power, which is the basis for a significant amount of Congressional legislation. Slaughterhouse i. Brief Fact Summary. A Louisiana statute granting a monopoly over the butchering trade in three areas of the state was unsuccessfully challenged by Plaintiffs, butchers not included in the monopoly, under the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Amendments. ii. Synopsis of Rule of Law. The Thirteenth Amendment does not empower individuals when their rights are taken, but rather is limited only to slavery. The purpose of the Fifteenth Amendment is to enforce the Thirteenth Amendment. The Privileges and Immunities clause only protects United States citizens, not state citizens. Thus, only states can protect the rights of state citizens. iii. Facts. Louisiana passed a statute creating a monopoly over the butchering trade in three areas of the state in order to promote health and safety of the state citizens. The Plaintiffs, butchers who were excluded, sued claiming that the state law created an “involuntary servitude” in violation of the Thirteenth Amendment and that the law violated the Fourteenth Amendment by abridging the “privileges and immunities” of the citizens of the United States, thereby denying the Plaintiffs “the equal protection of the laws,” as well as “deprivation of their property without due process of law.” The highest state court sustained the law. iv. Issue. Whether state law created an “involuntary servitude” in violation of the Thirteenth Amendment. Whether the law violated the Fourteenth Amendment by abridging the “privileges and immunities” of the citizens of the United States, thereby denying Plaintiffs “the equal protection of the laws,” as well as “deprivation of their property without due process of law.” v. Held. No. Judgment of the highest state court affirmed. The purpose of the Thirteenth Amendment was to abolish slavery and to guarantee freedom to the “slave race.” The word “servitude” is personal in nature and can only be applied to slavery. No. Judgment of the highest state court affirmed. There is a distinction between citizenship of the United Constitutional Law Selected Terms and Cases h. i. States and citizenship of a state. Based on this distinction, the Privileges and Immunities Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment, which protects the “privileges and immunities of the United States citizens,” must differ from the content of the Article IV Section:2 Privileges and Immunities Clause, which protects the “privileges and immunities of citizens of the several states.” The federal privileges and immunities does not protect those rights protected by Article IV Section:2. Rather, the federal privileges and immunities clause merely required states to apply its laws equally to non-state residents, as well as state residents. Therefore, the Privileges and Immunities Clause under which the Plaintiffs sued does not provide protection for their claims. vi. Dissent. The privileges and immunities referred to in the Fourteenth Amendment include “the right to pursue lawful employment.” Since the Plaintiffs were denied such employment, the Clause should provide them with protection. The Fourteenth Amendment was meant to secure fundamental rights of any citizen against discrimination by his state. vii. Discussion. By holding that the Fourteenth Amendment Privileges and Immunities Clause did not afford protection to state citizens, the majority substantially limited the application of that Amendment. Lochner i. Freedom of Contract is a basic right ii. was a landmark United States Supreme Court case which held that "liberty of contract" was implicit in the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. The case involved a New York law that limited the number of hours that a baker could work each day to ten, and limited the number of hours that a baker could work each week to 60. By a 5–4 vote, the Supreme Court rejected the argument that the law was necessary to protect the health of bakers, deciding it was a labor law attempting to regulate the terms of employment, and calling it an "unreasonable, unnecessary and arbitrary interference with the right and liberty of the individual to contract." iii. Holme’s Dissent 1. He thinks that public opinion does matter. 2. Acuses the majority of being politically bias. iv. Tension between democratic legitimacy and the court West Coast Hotel i. Brief Fact Summary: Washington instituted a state wage minimum for women and minors. The Appellant, West Coast Hotel (Appellant), paid the Appellee, Parrish (Appellee), less than this minimum. ii. Synopsis of Rule of Law. Wage and hour laws generally do not violate the Due Process Clause of the United States Constitution (Constitution). iii. Facts. The Appellee was a maid who worked for less than the state minimum of $14.50 per 48-hour week. She brought suit to recover the difference in pay from the Appellant. iv. Issue. Is the fixing of minimum wages for women and minors constitutional? v. Held. Yes. This case overrules Adkins v. Children’s Hospital. vi. The exploitation of a class of workers who are at a disadvantaged bargaining position is in the best interest of the health of the worker and economic health of the community. vii. Discussion. The Supreme Court of the United States (Supreme Court) reverts to reasoning that women are in an inferior position and need to be protected from those who might try to take advantage of the situation. Furthermore, the state is justified in adopting such legislation to protect the rest of the community from the burden of supporting economically disadvantaged workers. It is important to note that the Depression colored the Supreme Court’s analysis. 53. Carolene Products footnote: The Carolene Products footnote introduced the different levels of scrutiny. Constitutional Law Selected Terms and Cases 54. First Amendment- Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof; or abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press; or the right of the people peaceably to assemble, and to petition the Government for a redress of grievances. 55. Fourth Amendment- The right of the people to be secure in their persons, houses, papers, and effects, against unreasonable searches and seizures, shall not be violated, and no Warrants shall issue, but upon probable cause, supported by Oath or affirmation, and particularly describing the place to be searched, and the persons or things to be seized. 56. Fifth Amendment-No person shall be held to answer for a capital, or otherwise infamous crime, unless on a presentment or indictment of a Grand Jury, except in cases arising in the land or naval forces, or in the Militia, when in actual service in time of War or public danger; nor shall any person be subject for the same offence to be twice put in jeopardy of life or limb; nor shall be compelled in any criminal case to be a witness against himself, nor be deprived of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law; nor shall private property be taken for public use, without just compensation. 57. Sixth Amendment-In all criminal prosecutions, the accused shall enjoy the right to a speedy and public trial, by an impartial jury of the State and district wherein the crime shall have been committed, which district shall have been previously ascertained by law, and to be informed of the nature and cause of the accusation; to be confronted with the witnesses against him; to have compulsory process for obtaining witnesses in his favor, and to have the Assistance of Counsel for his defence. 58. Ninth Amendment- The enumeration in the Constitution, of certain rights, shall not be construed to deny or disparage others retained by the people. 59. Exclusionary rule- rule that forbids the use of illegally obtained evidence. 60. “the freedom of speech”a. protected under the first amendment of the constitution 61. “the free exercise of religion”protected under the first amendment of the constitution 62. the Establishment Clause: The Establishment Clause prohibits the government from interfering with individual religious beliefs. The government cannot enact laws aiding any religion or establishing an official state religion. The courts have interpreted the Establishment Clause to accomplish the separation of church and state on both the national and state levels of government. 63. immediately followed by the free exercise clause, which states, "or prohibiting the free exercise thereof". These two clauses make up what are called the "religion clauses" of the First Amendment. The Establishment Clause has generally been interpreted to prohibit a. the establishment of a national religion by Congress b. the preference by the U.S. government of one religion over another. The first approach is called the "separation" or "no aid" interpretation, while the second approach is called the "non-preferential" or "accommodation" interpretation. The accommodation interpretation prohibits Congress from preferring one religion over another, but does not prohibit the government's entry into religious domain to make accommodations in order to achieve the purposes of the Free Exercise Clause. 64. the right to privacy 65. the Warren Court: The Warren Court refers to the Supreme Court of the United States between 1953 and 1969, when Earl Warrenserved as Chief Justice. Warren led a liberal majority that used judicial power in dramatic fashion, to the consternation of conservative opponents. The Warren Court expanded civil rights, civil liberties, judicial power, and the federal power in dramatic ways. The court was both applauded and Constitutional Law Selected Terms and Cases criticized for bringing an end to racial segregation in the United States, incorporating the Bill of Rights (i.e. applying it to states), and ending officially sanctioned voluntary prayer in public schools. The period is recognized as a high point in judicial power that has receded ever since, but with a substantial continuing impact 66. “with all deliberate speed”- mentioned in the Brown decision which declared the system of legal segregation unconstitutional. However, the court only mentioned that the states should enforce the ruling “with all deliberate speed” rather than by a given deadline. The vagueness of this enforcement and allowed the segregationists to take as much time in following the brown ruling. 67. the Due Process Revolution: The Due Process Revolution was the process, carried out mostly by the Supreme Court under Chief Justice Earl Warren, of providing more due process rights to criminal defendants and others. The Due Process Revolution involved, among other things the "selective incorporation" of the Bill of Rights. This process required the states to adhere to the Bill of Rights even as the federal government did. The Due Process Revolution also added to the idea of what due process was. It added, for example, the idea that people who were arrested had to be read their rights (Miranda v. Arizona) before they could be interrogated. The Due Process Revolution, then, was a process of expanding the due process protections enjoyed by American citizens. 68. suspect classisfication: The suspect classification doctrine has its constitutional basis in the Fifth Amendment and the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment, and it applies to actions taken by federal and state governments. When a suspect classification is at issue, the government has the burden of proving that the challenged policy is constitutional. Race is the clearest example of suspect classification. 69. The Lemon test: The Court's decision in this case established the "Lemon test", which details the requirements for legislation concerning religion. It consists of three prongs:The government's action must have a secular legislative purpose; The government's action must not have the primary effect of either advancing or inhibiting rxeligion; The government's action must not result in an "excessive government entanglement" with religion. 70. Cases: a. Filburn, i. Background: The Agricultural Adjustment Act of 1938 limited the area that farmers could devote to wheat production. The stated purpose of the act was to stabilize the price of wheat in the national market by controlling the amount of wheat produced. This was a nationwide thing in which production can be regulated by the federal government. ii. Facts: Roscoe Filburn was a farmer who admitted producing wheat in excess of the amount permitted. He maintained, however, that the excess wheat was produced for his private consumption on his own farm. Since it never entered commerce at all, much less interstate commerce, he argued that it was not a proper subject of federal regulation under the Commerce Clause 1. Even though he was supposedly growing it himself it did affect the economy. 2. Because it was for his personal consumption it didn’t constitute interstate commerce. iii. Opinion: Intrastate commerce inevitably affects interstate commerce and because of the surplus, he wouldn’t be participating in the market because he has it all for himself. This was the Depression era. Intention to get people involved in the economy and if he isn’t participating he isn’t doing his jobs. Had a right to regulate because it effects interstate commerce. It is a national problem. iv. If the aggregate of activity has an effect on the economy Constitutional Law Selected Terms and Cases b. c. 1. Aggregation and substantial effect. v. They reject the former way of defining power. Whitney i. Brief Fact Summary. The California Criminal Syndicalism Act (the Act) prohibited any person to knowingly become a member of any organization that advocates “Criminal Syndicalism.” The Defendant, Anita Whitney (Defendant), was affiliated with an organization that adopted a “Left Wing Manifesto” and therefore convicted under the act. ii. Synopsis of Rule of Law. A State may constitutionally prohibit its citizens from knowingly being or becoming a member of an organization that advocates criminal syndicalism consistently with the First Amendment of the United States Constitution (Constitution). iii. Facts. The Act prohibited any person to knowingly become a member of any organization that advocates the commission of unlawful acts as a means of accomplishing a change in industrial ownership or effecting a political change. The Defendant was a member of the Oakland branch of the Socialist Party, which later formed the Communist Labor Party (”CLP”). The CLP adopted a Left Wing Manifesto similar to that at issue in Gitlow. Shortly thereafter, the Defendant attended a conference in Oakland for the purpose of organizing a California branch of the CLA. As a result, the Appellant was charged under the Act. iv. Issue. Did the Defendant’s knowingly being or becoming a member of an organization that advocated “criminal syndicalism” involve sufficient danger to the public peace that the State could constitutionally penalize her for it? v. Held. Yes. The lower court is affirmed. Justice Edward Sanford (J. Sanford) Because united and joint action involves even greater danger to the public peace and security than does single utterances and acts of individuals, it is not an unreasonable or arbitrary exercise of the police power of the State to prohibit the type of activity prohibited by the Act. Concurrence. Justice Louis Brandeis (J. Brandeis) Although the right to free speech is fundamental, it is not absolute. The right is subject to such restrictions as are required to protect the public from clear and imminent dangers. The Supreme Court of the United States (Supreme Court) has not yet fixed a standard by which to determine when such a degree of danger exists, but it has articulated the following guidelines: (1) fear of serious injury alone cannot justify suppression of free speech and assembly; (2) Even imminent danger cannot justify prohibitions on speech, unless the dangers apprehended are relatively serious. vi. Discussion. The Supreme Court is drawing a line here between expression rights exercised in the form of a conspiracy (i.e., rights of association) and expression rights exercised in the form of utterances. At issue in this case is the same type of statute that was at issue in Gitlow. The Supreme Court here, once again, upholds the statute but on different reasoning. J. Brandeis’ concurring opinion evinces a movement to a more stringent and contemporaneous regulation of free speech standard. Cohen i. Brief Fact Summary. The Defendant, Cohen’s (Defendant) conviction, for violating a California law by wearing a jacket that had “f— the draft” on it was reversed by the Supreme Court of the United States (Supreme Court) which held such speech was protected. ii. Synopsis of Rule of Law. Emotive speech that is used to get attention is protected by the constitution. iii. Facts. The Defendant was convicted under a California law for wearing a jacket that had on it, “F— the draft” outside the municipal courthouse during the Vietnam War. The Defendant did not threaten or engage in any act of violence. The state court affirmed his conviction holding that “offensive conduct” means “behavior which has a tendency to provoke others to acts of violence or to in turn disturb the peace.” Constitutional Law Selected Terms and Cases iv. d. Issue. Whether California can excise, as “offensive conduct,” one particular scurrilous epithet from the public discourse, either upon the theory of the court below that its use is inherently likely to cause violent reactions or upon a more general assertion that the states, acting as guardians of the public morality, may properly remove this offensive word from the public vocabulary? v. Held. No. Judgment of the lower courts reversed. Defendant’s speech is protected by the First Amendment of the United States Constitution (Constitution). The only conviction that the state sought to punish was communication. Thus, this case rests solely upon “speech.” The state lacks power to punish Defendant for the content of his message because he showed no intent to incite disobedience to the draft. Thus, his conviction rests upon his exercise of the “freedom of speech” and can only be justified as a valid regulation of the manner in which he exercised that freedom. This is not an obscenity case because his message is not erotic. This case does not involve “fighting words” because his message is not directed at another person. Further, the public is free to avert their eyes from the distasteful message. His message constitutes emotive speech because it seeks to get our attention. This speech is protected by the First Amendment of the Constitution. Therefore, his conviction must be overturned. vi. Dissent. Defendant’s conviction should be sustained because his antic was mainly conduct and the case involves “fighting words.” vii. Discussion. This case categorizes a new kind of speech, emotive speech. It also holds that it is not enough to find speech unprotected merely because it creates a disturbance to the public. Morse i. Brief Fact Summary: Joseph Frederick, a senior at Juneau-Douglas High School, unfurled a banner saying "Bong Hits 4 Jesus" during the Olympic Torch Relay through Juneau, Alaska on January 24, 2002. Frederick's attendance at the event was part of a school-supervised activity. The school's principal, Deborah Morse, told Frederick to put away the banner, as she was concerned it could be interpreted as advocating illegal drug activity. After Frederick refused to comply, she took the banner from him. Frederick originally was suspended from school for 10 days for violating school policy, which forbids advocating the use of illegal drugs. ii. Procedure: The U.S. District Court for the District of Alaska ruled for Morse, saying that Frederick's action was not protected by the First Amendment. The U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit reversed and held that Frederick's banner was constitutionally protected. The U.S. Supreme Court granted certiorari. iii. Issues: Whether a principal violates the Free Speech Clause of the First Amendment by restricting speech at a school-supervised event when the speech is reasonably viewed as promoting illegal drug use. iv. Ruling: No. v. Reasoning: In Tinker v. Des Moines (1969), the Court stated that students do not "shed their constitutional rights to freedom of speech or expression at the schoolhouse gate." Tinker held that the wearing of armbands by students to protest the Vietnam War was constitutionally protected speech because it was political speech. Political speech is at the heart of the First Amendment and, thus, can only be prohibited if it "substantially disrupts" the educational process. On the other hand, the Court noted in Bethel v. Fraser, 478 U.S. 675, 682 (1986) that "the constitutional rights of students at public school are not automatically, coextensive with the rights of adults." The rights of students are applied "in light of the special characteristics of the school environment," according to the U.S. Supreme Court in Hazelwood School District v. Kuhlmeier, 484 U.S. 260, 266 (1988). In the present case, the majority acknowledged that the Constitution affords lesser Constitutional Law Selected Terms and Cases e. f. protections to certain types of student speech at school or school-supervised events. Finding that the message Frederick displayed was by his own admission not political in nature, as was the case in Tinker, the Court said the phrase "Bong Hits 4 Jesus" reasonably could be viewed as promoting illegal drug use. As such, the state had an "important" if not "compelling" interest in prohibiting/punishing student speech that reasonably could be viewed as promoting illegal drug use. The Court, therefore, held that schools may "take steps to safeguard those entrusted to their care from speech that can reasonably be regarded as encouraging illegal drug use" without fear of violating a student's First Amendment rights. Korematsu i. Brief Fact Summary. During World War II, a military commander ordered all persons of Japanese descent to evacuate the West Coast. The Petitioner, Korematsu (Petitioner), a United States citizen of Japanese descent, was convicted for failing to comply with the order. ii. Synopsis of Rule of Law. Legal restrictions that curtail the civil rights of a single racial group are subject to the most rigid scrutiny. But, pressing public necessity may sometimes justify such restrictions. iii. Facts. President of the United States Franklin Roosevelt (President Roosevelt) issued an executive order authorizing military commanders to prescribe military areas from which any or all persons may be excluded. Thereupon, a military commander ordered all persons of Japanese descent, whether or not they were United States citizens, to leave their homes on the West Coast and to report to “Assembly Centers.” The Petitioner, a United States citizen of unchallenged loyalty, but of Japanese descent, was convicted under a federal law making it an offense to fail to comply with such military orders. iv. Issue. Was it within the power of Congress and the Executive to exclude persons of Japanese ancestry from the West Coast at the time that they were excluded? v. Held. Yes. At the time the exclusion was ordered, it was justified. Justice Hugo Black stated that although the exclusion order imposed hardships upon a large number of American citizens, hardships are part of war. When, under conditions of warfare, our shores are threatened by hostile forces, the power to protect them must be commensurate with the threatened danger. vi. Dissent. Justice Frank Murphy (J. Murphy) argued that the exclusion at issue here goes over the brink of constitutional power and falls into the abyss of racism. Although we must extend great deference to the judgments of the military, it is essential that there be definite limits to military discretion. Moreover, the military order is not reasonably related to the dangers it seeks to prevent. Justice Robert Jackson (J. Jackson) stated he would not distort the United States Constitution (Constitution) to approve everything the military may deem expedient. vii. Discussion. Ironically, this case establishes the “strict scrutiny” standard of review, thereby leading to the invalidation of much race-based discrimination in the future. Barnette i. Brief Fact Summary. The Respondent, Barnette (Respondent), is a Jehovah’s Witness who refused to pledge allegiance the United States flag while in public school. According to the Petitioner, the West Virginia State Board of Education’s (Petitioner), rule, the Respondent was expelled from school and charged with juvenile delinquency. ii. Synopsis of Rule of Law. The right to not speak is as equally protected under the First Amendment of the United States Constitution (Constitution) as the right to free speech. iii. Facts. In 1942, the Petitioner adopted a rule that forced all teachers and pupils to pledge allegiance the nation’s flag each day. If the student refused he would be found insubordinate and expelled from school. He would not be readmitted to school until he Constitutional Law Selected Terms and Cases g. h. conformed. Meanwhile, he was considered to be “unlawfully absent” and subject to delinquency hearings. The parents could be fined $50 per day with a jail term not to exceed 30 days. The Respondent asked for an exception for all Jehovah’s Witnesses because this pledge goes against their religious belief. But he was denied an exception. iv. Issue. Does this rule compelling a pledge violate the First Amendment of the Constitution? Is this a case about the freedom of speech or the freedom of religion? v. Held. Yes. Compelling a salute to the flag infringes upon an individual’s intellect and right to choose their own beliefs. vi. Dissent. This legislation is well within the states purview to encourage good citizenship. vii. Discussion. The majority focuses on the right of persons to choose beliefs and act accordingly. As long as the actions do not present a clear and present danger of the kind the state is allowed to prevent, then the Constitution encourages diversity of thought and belief. The state has not power to mandate allegiance in hopes that it will encourage patriotism. This is something the citizens will choose or not. Sweatt i. Facts: In 1946, Heman Marion Sweatt, a black man, applied for admission to the University of Texas Law School. State law restricted access to the university to whites, and Sweatt's application was automatically rejected because of his race. When Sweatt asked the state courts to order his admission, the university attempted to provide separate but equal facilities for black law students. They made another law school but he refused to go there because of ii. Question: Did the Texas admissions scheme violate the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment? iii. Conclusion:In a unanimous decision, the Court held that the Equal Protection Clause required that Sweatt be admitted to the university. The Court found that the "law school for Negroes," which was to have opened in 1947, would have been grossly unequal to the University of Texas Law School. The Court argued that the separate school would be inferior in a number of areas, including faculty, course variety, library facilities, legal writing opportunities, and overall prestige. The Court also found that the mere separation from the majority of law students harmed students' abilities to compete in the legal arena. Sweatt was admitted. Brown v. Board I i. Brief Fact Summary: Black children were denied admission to schools attended by white children under laws that permitted or required segregation by race. The children sued. ii. Ruling: Separate but equal educational facilities are inherently unequal iii. Facts: The Plantiffs, various black children, were denied admission to schools attended by white children under laws that permitted or required segregation by race. Plantiffs sued, seeking admission to public schools in their communities on a nonsegregated basis. iv. Issue: Do separate but equal laws in the area of public education deprive black children of the equal protection of the laws guaranteed by the Fourteenth Amendment of the Constitution? v. Held: Yes. Chief Justice Earl Warren stated that even if the “tangible” factors of segregated schools are equal, to separate black children from others of similar age and qualfications solely on the basis of race, genereates a feeling of inferiority with respect to their status in the community and may affect their hearts and minds in a way unlikely to ever be undone. vi. Discussion: The Supreme Court of the United States (Supreme Court) is relying on the same rationale to invalidate the segregation laws here that it did in Sweatt v. Painter (ordering the admission of a black student to the University of Texas Law School, despite the fact that a parallel black facility was available). The rationale is that it’s the intangible Constitutional Law Selected Terms and Cases i. j. k. factors that make segregation laws in the area of public education “inherently unequal.” Whether stigma or the perception of stigma alone is sufficient injury to invalidate a law supported by a valid, neutral purpose is an open question. Brown v. Board II Cooper v. Aaron i. Synopsis of Rule of Law. The Constitution is the Supreme Law of the Land; Supreme Court Cases are binding upon all the States. ii. Facts. A state governor wishes to have the state legislature make it legal to segregate children in school based on his or her race. The Governor’s argument is one that the case is only binding until the state legislates otherwise, and that the case of Brown v. Board of Education should not be binding on the state. iii. Issue. Whether a state is bound by all Supreme Court Case decisions. iv. Held. Yes. Every state is bound by not only the United States Constitution, but also all cases decided by the United State Supreme Court. While each state has its own sovereignty, that sovereignty is granted by the United States Constitution. That is where the State derives its power from. In that same document it states that the United States Constitution is the Supreme law of the Land. In 1803 the bench stated that federal law is the fundamental and paramount law of the nation. The United States Constitution under the 14th amendment will not allow States to discriminate against children based on their race. Also no state may wage war against the federal government. v. Discussion. Not only was the Brown decision unanimously reached in the original decision, even today, with three new justices, that decision is still affirmed unanimously today. A state through its legislature may not use evasive schemes to achieve segregation. Brown v. Mississippi i. Brief Fact Summary. Two individuals were convicted of murder, the only evidence of which was their own confessions that were procured after violent interrogation. ii. Synopsis of Rule of Law. The Fourteenth Amendment Due Process Clause is violated when a confession obtained via physical torture is used to convict a defendant. iii. Facts. The Petitioners were indicted for a murder that occurred on March 30, 1934. The Petitioners were indicted on April 4, 1934, arraigned thereafter and then pleaded not guilty. The Petitioners were found guilty after a trial solely on the basis of their confessions. During the trial, the Petitioners testified that the confessions were untrue and procured after physical torture. The Petitioners appealed to the Supreme Court of Mississippi arguing that their Fourteenth Amendment rights were violated. The Supreme Court of Mississippi affirmed the trial court’s judgment. The Mississippi Supreme Court concluded “(1) that immunity from self- incrimination is not essential to due process of law; and (2) that the failure of the trial court to exclude the confessions after the introduction of evidence showing their incompetency, in the absence of a request for such exclusion, did not deprive the defendants of life or liberty without due process of law; and that even if the trial court had erroneously overruled a motion to exclude the confessions, the ruling would have been mere error reversible on appeal, but not a violation of constitution right.” The state’s highest court also observed “[a]fter the state closed its case on the merits, the appellants, for the first time, introduced evidence from which it appears that the confessions were not made voluntarily but were coerced.” iv. Issue. “[W]hether convictions, which rest solely upon confessions shown to have been extorted by officers of the state by brutality and violence, are consistent with the due process of law required by the Fourteenth Amendment of the Constitution of the United States[?]” v. Held. The state argued that pursuant to Twining v. New Jersey the “exemption from Constitutional Law Selected Terms and Cases l. compulsory self-incrimination in the courts of the states is not secured by any part of the Federal Constitution”. The state also relied on Snyder v. Massachusetts where the Supreme Court of the United States (”Supreme Court”) found “the privilege against self-incrimination may be withdrawn and the accused put upon the stand as a witness for the state.” The majority disregarded these arguments and observed “[b]ut the question of the right of the state to withdraw the privilege against self-incrimination is not here involved. The compulsion to which the quoted statements refer is that of the processes of justice by which the accused may be called as a witness and required to testify. Compulsion by torture to extort a confession is a different matter.”Further, “[t]he state is free to regulate the procedure of its courts in accordance with its own conceptions of policy, unless in so doing it ‘offends some principle of justice so rooted in the traditions and conscience of our people as to be ranked as fundamental.’ ” However, “the freedom of the state in establishing its policy is the freedom of constitutional government and is limited by the requirement of due process of law.” Here, “the trial equally is a mere pretense where the state authorities have contrived a conviction resting solely upon confessions obtained by violence.” Accordingly, “[t]he due process clause requires ‘that state action, whether through one agency or another, shall be consistent with the fundamental principles of liberty and justice which lie at the base of all our civil and political institutions.” Moreover, “[i]t would be difficult to conceive of methods more revolting to the sense of justice than those taken to procure the confessions of these petitioners, and the use of the confessions thus obtained as the basis for conviction and sentence was a clear denial of due process.” The majority observed, “the trial court was fully advised by the undisputed evidence of the way in which the confessions had been procured. The trial court knew that there was no other evidence upon which conviction and sentence could be based. Yet it proceeded to permit conviction and to pronounce sentence. The conviction and sentence were void for want of the essential elements of due process, and the proceeding thus vitiated could be challenged in any appropriate manner.” vi. Discussion. This case illustrates how federal constitutional rights also often times apply to the states through the Fourteenth Amendment Due Process Clause. Mapp i. Brief Fact Summary. Police officers sought a bombing suspect and evidence of the bombing at the petitioner, Miss Mapp’s (the “petitioner”) house. After failing to gain entry on an initial visit, the officers returned with what purported to be a search warrant, forcibly entered the residence, and conducted a search in which obscene materials were discovered. The petitioner was tried and convicted for these materials. ii. Synopsis of Rule of Law. All evidence discovered as a result of a search and seizure conducted in violation of the Fourth Amendment of the United States Constitution (”Constitution”) shall be inadmissible in State court proceedings. iii. Facts. Three Cleveland police officers arrived at the petitioner’s residence pursuant to information that a bombing suspect was hiding out there and that paraphernalia regarding the bombing was hidden there. The officers knocked and asked to enter, but the petitioner refused to admit them without a search warrant after speaking with her attorney. The officers left and returned approximately three hours later with what purported to be a search warrant. When the petitioner failed to answer the door, the officers forcibly entered the residence. The petitioner’s attorney arrived and was not permitted to see the petitioner or to enter the residence. The petitioner demanded to see the search warrant and when presented, she grabbed it and placed it in her shirt. Police struggled with the petitioner and eventually recovered the warrant. The petitioner was then placed under arrest for being belligerent and taken to her bedroom on the second floor of the residence. The officers then conducted a widespread search of the residence wherein obscene materials were Constitutional Law Selected Terms and Cases found in a trunk in the basement. The petitioner was ultimately convicted of possessing these materials. iv. Issue. Whether evidence discovered during a search and seizure conducted in violation of the Fourth Amendment of the Constitution shall be admissible in a State court? v. Held. Justice Tom Clark (”J. Clark”) filed the majority opinion. No, the exclusionary rule applies to evidence obtained in violation of the Fourth Amendment’s search and seizure clause in all State prosecutions. Since the Fourth Amendment’s right of privacy has been declared enforceable against the States through the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment, the same sanction of exclusion is also enforceable against them. The purpose of the exclusionary rule is to deter illegally obtaining evidence and to compel respect for the constitutional guarantee in the only effective manner. Otherwise, a State, by admitting illegally obtained evidence, disobeys the Constitution that it has sworn to uphold. A federal prosecutor may make no use of illegally obtained evidence, but a State prosecutor across the street may, although he supposedly is operating under the enforceable prohibitions of the same Amendment. If the criminal is to go free, then it must be the law that sets him free. Our government is the potent, omnipresent teacher. For good or for ill, it teaches the whole people by its example. If the government becomes a lawbreaker, it breeds contempt for law. vi. Dissent. Justice John Harlan (”J. Harlan”) filed a dissenting opinion joined by Justice Felix Frankfurter (”J. Frankfurter”) and Justice Charles Whittaker (”J. Whittaker”). A recent study shows that one half of the States still adhere to the common-law non-exclusionary rule. The main concern is not the desirability of the rule, but whether the States should be forced to follow it. This Court should continue to forbear from fettering the States with an adamant rule which may embarrass them in coping with their own peculiar problems in criminal law enforcement. vii. Concurrence.Justice Hugo Black (”J. Black”) filed a concurring opinion. When the Fourth Amendment’s ban against unreasonable searches and seizures is considered together with the Fifth Amendment’s ban against compelled self-incrimination, a constitutional basis emerges which not only justifies, but actually requires the exclusionary rule. Justice William Douglas (”J. Douglas”) filed a concurring opinion. He believed this to be an appropriate case in which to put an end to the asymmetry which Wolf imported into the law. viii. Discussion. This case explicitly overrules Wolf v. Colorado, 338 U.S. 25 (1949). The federal exclusionary rule now applies to the States through application of the Fourteenth Amendment of the Constitution. All illegally obtained evidence under the Fourth Amendment of the Constitution must now be excluded. m. Gideon v. Wainright i. Brief Fact Summary. Gideon was charged with a felony in Florida state court. He appeared before the state Court, informing the Court he was indigent and requested that the Court appoint him an attorney. The Court declined to appoint Gideon an attorney, stating that under Florida law, the only time an indigent defendant is entitled to appointed counsel is when he is charged with a capital offense. ii. Synopsis of Rule of Law. This case overruled Betts and held that the right of an indigent defendant to appointed counsel is a fundamental right, essential to a fair trial. Failure to provide an indigent defendant with an attorney is a violation of the Fourteenth Amendment of the United States Constitution (”Constitution”). iii. Facts. Gideon was charged in a Florida state court with breaking and entering into a poolroom with the intent to commit a misdemeanor. Such an offense was a felony under Florida law. When Gideon appeared before the state Court he informed the court that he was indigent and requested the Court appoint him an attorney, asserting that “the United Constitutional Law Selected Terms and Cases n. States Supreme Court says I am entitled to be represented by counsel.” The se Court informed Gideon that under Florida law only indigent clients charged with capital offenses are entitled to court appointed counsel. Gideon proceeded to a jury trial; made an opening statement, cross-examined the State’s witnesses, called his own witnesses, declined to testify himself; and made a closing argument. The jury returned a guilty verdict and Gideon was sentenced to serve five years in state prison. While serving his sentence, Gideon filed a petition for habeas corpus attacking his conviction and sentence on the ground that the trial court’s refusal to appoint counsel denied his constitutional rights and rights guaranteed him under the Bill of Rights. The Florida State Supreme Court denied relief. Because the problem of a defendant’s constitutional right to counsel in state court continued to be source of controversy since Betts v. Brady, the United States Supreme Court (”Supreme Court”) granted certiorari to again review the issue. iv. Issue. Whether the Sixth Amendment constitutional requirement that indigent defendants be appointed counsel is so fundamental and essential to a fair trial that it is made obligatory on the states by the Fourteenth Amendment of the Constitution? v. Held. The right to counsel is a fundamental right essential to a fair trial and due process of law. Concurrence. Justice Tom Clark (”J. Clark”) concurred and recognized that the Sixth Amendment of the Constitution clearly required appointment of counsel in “all criminal prosecutions” and that the Fourteenth Amendment of the Constitution requires appointment of counsel in all prosecutions for capital crimes. The instant decision does no more than erase an illogical distinction. J. Clark further concludes that the Constitution makes no distinction between capital and noncapital cases. The Fourteenth Amendment requires due process of law for the deprivation of liberty just as equally as it does for deprival of life. Accordingly, there cannot be a constitutional distinction in the quality of the process based merely upon the sanction to be imposed. Justice John Harlan (”J. Harlan”): Agrees that Betts v. Brady should be overruled, but argues that Betts recognized that there might be special circumstances in non capital cases requiring the appointment of counsel. In non capital cases the special circumstances continued to exist, but have been substantially and steadily eroded, culminating in the instant decision. J. Harlan clarified his view that he does not believe that the Fourteenth Amendment of the Constitution incorporates the entire Sixth Amendment resulting in all federal law applies to all the States. J. Harlan still wants to preserve to the States their independence to make law and procedures consistent with the divergent problems and legitimate interests that the States face that are difference from each other and different from the Federal Government. vi. Discussion. The Supreme Court, in reaching its conclusion that the right to counsel is a fundamental right imposed upon the states pursuant to the Fourteenth Amendment of the Constitution, engages in an analysis of its previous decisions holding that other provisions of the Bill of Rights are fundamental rights made obligatory on the States. The Supreme Court accepts the Betts v. Brady assumption that a provision of the Bill of Rights which is fundamental and essential to a fair trial is made obligatory on the states by the Fourteenth Amendment of the Constitution. The Supreme Court diverges from Betts in concluding that the right to assistance of counsel is a fundamental right. The Supreme Court found that the Betts Court’s conclusion that assistance of counsel is not a fundamental right was an abrupt break from its own well-considered precedent. The Supreme Court further reasons that the right to be heard at trial would be, in many cases, of little avail without the assistance of counsel who is familiar with the rules of court, the rules of evidence and the general procedure of the court system. Without the assistance of counsel “though he be not guilty, he faces the danger of conviction because he does not know how to establish his innocence.” Terry v. Ohio Constitutional Law Selected Terms and Cases i. o. Brief Fact Summary. The Petitioner, John W. Terry (the “Petitioner”), was stopped and searched by an officer after the officer observed the Petitioner seemingly casing a store for a potential robbery. The officer approached the Petitioner for questioning and decided to search him first. ii. Synopsis of Rule of Law. An officer may perform a search for weapons without a warrant, even without probable cause, when the officer reasonably believes that the person may be armed and dangerous. iii. Facts. The officer noticed the Petitioner talking with another individual on a street corner while repeatedly walking up and down the same street. The men would periodically peer into a store window and then talk some more. The men also spoke to a third man whom they eventually followed up the street. The officer believed that the Petitioner and the other men were “casing” a store for a potential robbery. The officer decided to approach the men for questioning, and given the nature of the behavior the officer decided to perform a quick search of the men before questioning. A quick frisking of the Petitioner produced a concealed weapon and the Petitioner was charged with carrying a concealed weapon. iv. Issue. Whether a search for weapons without probable cause for arrest is an unreasonable search under the Fourth Amendment to the United States Constitution (”Constitution”)? v. Held. The Supreme Court of the United States (”Supreme Court”) held that it is a reasonable search when an officer performs a quick seizure and a limited search for weapons on a person that the officer reasonably believes could be armed. A typical beat officer would be unduly burdened by being prohibited from searching individuals that the officer suspects to be armed. vi. Dissent. Justice William Douglas (”J. Douglas”) dissented, reasoning that the majority’s holding would grant powers to officers to authorize a search and seizure that even a magistrate would not possess. vii. Concurrence. Justice John Harlan (”J. Harlan”) agreed with the majority, but he emphasized an additional necessity of the reasonableness of the stop to investigate the crime. Justice Byron White (”J. White”) agreed with the majority, but he emphasized that the particular facts of the case, that there was suspicion of a violent act, merit the forcible stop and frisk. viii. Discussion. The facts of the case are important to understand the Supreme Court’s willingness to allow the search. The suspicious activity was a violent crime, armed robbery, and if the officer’s suspicions were correct then he would be in a dangerous position to approach the men for questioning without searching them. The officer also did not detain the men for a long period of time to constitute an arrest without probable cause. Muller i. Brief Fact Summary. The Petitioner, Muller (Petitioner), was found guilty of violating Oregon state statute that limited the length of the workday for women in laundry facilities. ii. Synopsis of Rule of Law. The general right to contract is protected by the United States Constitution (Constitution), but this liberty is not absolute. iii. Facts. In 1903, Oregon passed a statute limiting the hours a woman can work to just 10 hours if she was employed in a laundry, factory or mechanical manufacturer. The reasoning for the law was, “the physical organization of women, her maternal functions, the rearing and education of children and the maintenance of the home.” iv. Issue. Is a state statute limiting the length of a woman’s workday constitutional? v. Held. Yes. Women, like minors, are a special class of worker that needs protection. This statute is within the state’s police power to protect the health of the general public because the physical well-being of women is paramount to the production of healthy Constitutional Law Selected Terms and Cases p. q. offspring. vi. Discussion. The Supreme Court of the United States (Supreme Court) defines women as a class needing protection based on the traditional concepts of a woman’s role in society. The discussion focuses heavily on the physical weakness of women and their inherent reliance on men for support. Women are compared to children and implied not completely competent to enter into their own labor contracts. Hogan i. Brief Fact Summary. The Respondent, Hogan (Respondent), was denied admission to Mississippi University for Women’s (MUW) nursing program solely on the basis of gender. He now alleges this is a denial of equal protection. ii. Synopsis of Rule of Law. A state may not preclude one gender or the other from participating in a unique educational environment solely on the basis of gender. iii. Facts. MUW is the only single-sex collegiate institution maintained by the State of Mississippi. The Respondent was otherwise qualified for admission to the school’s nursing program, but he was denied admission on the basis of being male. iv. Issue. Does the operation of a female only nursing school by a State violate Equal Protection? v. Held. Yes. Appeals Court ruling affirmed. Applying intermediate scrutiny, Justice Sandra Day O’Connor (J. O’Connor) notes that the State of Mississippi has not advanced an important state interest for operating a single sex nursing school. In particular, she notes that women did not lack opportunities to be trained as nurses in Mississippi without the presence of MUW. J. O’Connor also argues that the means to achieving even an important governmental objective (although she found none) are absent, as MUW allows male auditors in the nursing classes. If men are already in the classroom, the state is not technically operating a single-sex nursing program. vi. Dissent. Justice Lewis Powell (J. Powell) argues that the Respondent has not suffered a cognizable injury, as there were state-operated nursing programs that accepted men elsewhere in the state and there is no right to attend a state-run university close to one’s hometown. vii. Discussion. The majority focuses on whether Mississippi may discriminate against men in admission to nursing programs. However, there are two powerful arguments brought up by the dissent. The first is the lack of injury argument – without injury a case is not ripe, and the constitutional issue may not be reached. There is also the argument that as there is no unique educational opportunity here (there are nursing programs accepting men in the State college system), the state is not denying opportunities to men. US v Virginia i. Brief Fact Summary. Virginia Military Institute (VMI) was the only single-sexed school in Virginia. VMI used a highly adversarial method to train (male) leaders of the future. There was no equal educational opportunity to that of VMI in the State for women. ii. Synopsis of Rule of Law. Gender-based classifications of the government can be defended only by exceedingly persuasive justifications. The State must show that its classification serves important governmental objectives and that the means employed are substantially related to those objectives. The justification must be genuine, not hypothesized. And it must not rely on overbroad generalizations about the differences between males and females. iii. Facts. VMI was the sole single-sexed school among Virginia’s 15 public institutions. VMI’s mission is to produce “citizen soldiers”, (male) leaders of the future. VMI achieves its mission through its “adversative method”, which is characterized by physical rigor, mental stress, absolute equality of treatment, absence of privacy, etc. At trial, the District Court acknowledged that women were missing out on a unique educational opportunity, but Constitutional Law Selected Terms and Cases r. upheld the school’s policy on the rationale that admitting women could not be done without compromising the school’s adversative method. Pursuant to a decision by the Court of Appeals, the State established the Virginia Women’s Institute for Leadership (VWIL) for women. VWIL offered fewer courses than VMI and was run without the adversative method. iv. Issue. Did VMI represent a violation of the Fourteenth Amendment’s Equal Protection Clause? v. Held. Yes. The Fourth Circuit’s initial judgment is affirmed. Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg (J. Ginsburg) stated that Virginia has shown no “exceedingly persuasive justification” for excluding all women. “Benign” justifications offered in defense of absolute exclusions will not be accepted automatically. The notion that admitting women would downgrade VMI’s stature and destroy the school’s adversity system was hardly proved.Generalizations about the way women are or what is appropriate for them will no longer serve to justify denying opportunity to those whose talents and capabilities make them exceptions to the average description. Moreover, VWIL does not qualify as VMI’s substitute. VWI’s student body, faculty, course offerings and facilities do not match VMI’s. vi. Dissent. Justice Antonin Scalia (J. Scalia) said the virtue of a democratic system is that it enables people over time to be persuaded that the things they took for granted are not so and to change their laws accordingly. That system is destroyed if such types of decisions are removed from the democratic process and written into our United States Constitution (Constitution). vii. Concurrence. Chief Justice William Rehnquist (J. Rehnquist) argued that while he agreed with the Supreme Court’s conclusion, he disagreed with its analysis. The Supreme Court says here for the first time the state must show an “exceedingly persuasive” justification for gender-based classifications, thereby introducing uncertainty regarding the appropriate test. In addition, VWIL only fails as a remedy because it is of inferior quality to VMI. viii. Discussion. This case calls into question what differences between men and women are real, i.e., legitimate basis upon which to draw distinctions, for constitutional purposes. Griswold i. Brief Fact Summary. Appellants were charged with violating a statute preventing the distribution of advice to married couples regarding the prevention of conception. Appellants claimed that the statute violated the 14th Amendment to the United States Constitution. ii. Synopsis of Rule of Law. The right of a married couple to privacy is protected by the Constitution. iii. Facts. Appellant Griswold, Executive Director of the Planned Parenthood League of Connecticut and Appellant Buxton, a licensed physician who served as Medical Director for the League at its Center in New Haven, were arrested and charged with giving information, instruction, and medical advice to married persons on means of preventing conception. Appellants were found guilty as accessories and fined $100 each. Appellants appealed on the theory that the accessory statute as applied violated the 14th Amendment to the United States Constitution. Appellants claimed standing based on their professional relationship with the married people they advised. iv. Issue. Does the Constitution provide for a privacy right for married couples? v. Held. The First Amendment has a penumbra where privacy is protected from governmental intrusion, which although not expressly included in the Amendment, is necessary to make the express guarantees meaningful. The association of marriage is a privacy right older than the Bill of Rights, and the State’s effort to control marital activities in this case is unnecessarily broad and therefore impinges on protected Constitutional freedoms. Constitutional Law Selected Terms and Cases s. vi. Dissent. Justice Stewart and Justice Black. Although the law is silly, it is not unconstitutional. The citizens of Connecticut should use their rights under the 9th and 10th Amendment to convince their elected representatives to repeal it if the law does not conform to their community standards. vii. Concurrence. Justice Goldberg, the Chief Justice, and Justice Brennan. The right to privacy in marriage is so basic and fundamental that to allow it to be infringed because it is not specifically addressed in the first eight amendments is to give the 9th Amendment no effect. Justice Harlan. The relevant statute violates the Due Process Clause of the 14th Amendment because if violates the basic values implicit in the concept of ordered liberty. viii. Discussion. The right to privacy in marriage is not specifically protected in either the Bill of Rights or the Constitution. Nonetheless, it is a right so firmly rooted in tradition that its protection is mandated by various Constitutional Amendments, including the 1st, 9th and 14th Amendments. Roe v. Wade i. Brief Fact Summary. Appellant Jane Roe, a pregnant mother who wished to obtain an abortion, sued on behalf of all woman similarly situated in an effort to prevent the enforcement of Texas statutes criminalizing all abortions except those performed to save the life of the mother. ii. Synopsis of Rule of Law. Statutes that make criminal all abortions except when medically advised for the purpose of saving the life of the mother are an unconstitutional invasion of privacy. iii. Facts. Texas statutes made it a crime to procure or attempt an abortion except when medically advised for the purpose of saving the life of the mother. Appellant Jane Roe sought a declaratory judgment that the statutes were unconstitutional on their face and an injunction to prevent defendant Dallas County District Attorney from enforcing the statutes. Appellant alleged that she was unmarried and pregnant, and that she was unable to receive a legal abortion by a licensed physician because her life was not threatened by the continuation of her pregnancy and that she was unable to afford to travel to another jurisdiction to obtain a legal abortion. Appellant sued on behalf of herself and all other women similarly situated, claiming that the statutes were unconstitutionally vague and abridged her right of personal privacy, protected by the First, Fourth, Fifth, Ninth, and Fourteenth Amendments. iv. Issue. Do the Texas statutes improperly invade a right possessed by the appellant to terminate her pregnancy embodied in the concept of personal liberty contained in the Fourteenth Amendment’s Due Process Clause, in the personal marital, familial, and sexual privacy protected by the Bill of Rights or its penumbras, or among the rights reserved to the people by the Ninth Amendment? v. Held. The right to personal privacy includes the abortion decision, but the right is not unqualified and must be considered against important state interests in regulation. The abortion laws in effect in the majority of the States are of relatively recent vintage, deriving from statutory changes generally enacted in the latter half of the 19th century. At common law abortion performed before quickening (the first recognizable movement of the fetus in utero) was not an indictable offense, and it is doubtful that abortion was ever a firmly established common law crime even when it destroyed a quick fetus. Three reasons have been advanced for the historical enactment of criminal abortion laws. The first is that the laws are the product of a Victorian social concern to discourage illicit sexual conduct, but this argument has been taken seriously by neither courts nor commentators. The second reason is that the abortion procedure is hazardous, therefore the State’s concern is to protect pregnant women. However, modern medical techniques have altered the situation, with abortions being relatively safe particularly in the first trimester. The third reason is the Constitutional Law Selected Terms and Cases t. u. State’s interest is in protecting the prenatal life. However, this is somewhat negated by the fact that the pregnant woman cannot be prosecuted for the act of abortion. For the stage prior to the approximate end of the first trimester, the abortion decision must be left to the medical judgment of the pregnant woman’s attending physician, and may not be criminalized by statute. For the stage subsequent to the approximate end of the first trimester, the State may regulate abortion in ways reasonably related to maternal health based upon the State’s interest in promoting the health of the mother. For the stage subsequent to viability, the State may regulate and even proscribe abortion, except where necessary for the preservation of the mother’s life, based upon the State’s interest in the potential of the potential life of the unborn child. vi. Dissent. Justice Rehnquist. The right to an abortion is not universally accepted, and the right to privacy is thus not inherently involved in this case. vii. Discussion. The Court finds that an abortion statute that forbids all abortions except in the case of a life saving procedure on behalf of the mother is unconstitutional based upon the right to privacy. However, it does allow for regulation and proscription of abortion when the statute is narrowly tailored to uphold a compelling state interest, such as the health of the mother or the viable fetus. The court declined to address the question of when life begins. Akron- (1982) the city of akron provided 17 provisions attempting to regulate the performance of women’s abortions (examples of the provision included: no abortions after the first trimester, disposing of fetus in a “humane and sanitary manner” 1. Question 2. Did several provisions of the Akron ordinance violate a woman's right to an abortion as guaranteed by the Court's decision in Roe v. Wade and the rightto-privacy doctrine as implied by the Fourteenth Amendment? 3. The Court affirmed its commitment to protecting a woman's reproductive rights by invalidating the provisions of Akron's ordinance. Generally, Justice Powell's opinion reiterates the Court's findings in Roe and reasons that certain provisions of the ordinance violated the Constitution because they were clearly intended to direct women away from choosing the abortion option. They were not implemented out of medical necessities. The fetal disposal clause was struck down because its language was too vague to determine conduct subject to criminal prosecution. Casey 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. Facts of the Case The Pennsylvania legislature amended its abortion control law in 1988 and 1989. Among the new provisions, the law required informed consent and a 24 hour waiting period prior to the procedure. A minor seeking an abortion required the consent of one parent (the law allows for a judicial bypass procedure). A married woman seeking an abortion had to indicate that she notified her husband of her intention to abort the fetus. These provisions were challenged by several abortion clinics and physicians. A federal appeals court upheld all the provisions except for the husband notification requirement. Question Can a state require women who want an abortion to obtain informed consent, wait 24 hours, and, if minors, obtain parental consent, without violating their right to abortions as guaranteed by Roe v. Wade? Conclusion Decision: 5 votes for Planned Parenthood, 4 vote(s) against Constitutional Law Selected Terms and Cases 7. 8. v. z. Legal provision: Due Process In a bitter, 5-to-4 decision, the Court again reaffirmed Roe, but it upheld most of the Pennsylvania provisions. For the first time, the justices imposed a new standard to determine the validity of laws restricting abortions. The new standard asks whether a state abortion regulation has the purpose or effect of imposing an "undue burden," which is defined as a "substantial obstacle in the path of a woman seeking an abortion before the fetus attains viability." Under this standard, the only provision to fail the undue-burden test was the husband notification requirement. The opinion for the Court was unique: It was crafted and authored by three justices. ii. Everson Facts of the Case i. A New Jersey law allowed reimbursements of money to parents who sent their children to school on buses operated by the public transportation system. Children who attended Catholic schools also qualified for this transportation subsidy. ii. Question iii. Did the New Jersey statute violate the Establishment Clause of the First Amendment as made applicable to the states through the Fourteenth Amendment? iv. Conclusion v. No. A divided Court held that the law did not violate the Constitution. After detailing the history and importance of the Establishment Clause, Justice Black argued that services like bussing and police and fire protection for parochial schools are "separate and so indisputably marked off from the religious function" that for the state to provide them would not violate the First Amendment. The law did not pay money to parochial schools, nor did it support them directly in anyway. It was simply a law enacted as a "general program" to assist parents of all religions with getting their children to school. w. x. Engel y. Schempp Lemon i. Facts of the Case ii. This case was heard concurrently with two others, Earley v. DiCenso (1971) and Robinson v. DiCenso (1971). The cases involved controversies over laws in Pennsylvania and Rhode Island. In Pennsylvania, a statute provided financial support for teacher salaries, textbooks, and instructional materials for secular subjects to non-public schools. The Rhode Island statute provided direct supplemental salary payments to teachers in non-public elementary schools. Each statute made aid available to "church-related educational institutions." iii. Question iv. Did the Rhode Island and Pennsylvania statutes violate the First Amendment's Establishment Clause by making state financial aid available to "church- related educational institutions"? v. Argument vi. Lemon v. Kurtzman - Oral ArgumentLemon v. Kurtzman - Oral Argument (No. 569) vii. Conclusion viii. Decision: 8 votes for Lemon, 0 vote(s) against ix. Legal provision: Establishment of Religion x. Yes. Writing for the majority, Chief Justice Burger articulated a three-part test for laws dealing with religious establishment. To be constitutional, a statute must have "a secular legislative purpose," it must have principal effects which neither advance nor inhibit Constitutional Law Selected Terms and Cases religion, and it must not foster "an excessive government entanglement with religion." The Court found that the subsidization of parochial schools furthered a process of religious inculcation, and that the "continuing state surveillance" necessary to enforce the specific provisions of the laws would inevitably entangle the state in religious affairs. The Court also noted the presence of an unhealthy "divisive political potential" concerning legislation which appropriates support to religious schools. aa. Edwards 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. Facts of the Case A Louisiana law entitled the "Balanced Treatment for Creation-Science and Evolution-Science in Public School Instruction Act" prohibited the teaching of the theory of evolution in the public schools unless that instruction was accompanied by the teaching of creation science, a Biblical belief that advanced forms of life appeared abruptly on Earth. Schools were not forced to teach creation science. However, if either topic was to be addressed, evolution or creation, teachers were obligated to discuss the other as well. Question Did the Louisiana law, which mandated the teaching of "creation science" along with the theory of evolution, violate the Establishment Clause of the First Amendment as applied to the states through the Fourteenth Amendment? Legal provision: Establishment of Religion Yes. The Court held that the law violated the Constitution. Using the threepronged test that the Court had developed in Lemon v. Kurtzman (1971) to evaluate potential violations of the Establishment Clause, Justice Brennan argued that Louisiana's law failed on all three prongs of the test. First, it was not enacted to further a clear secular purpose. Second, the primary effect of the law was to advance the viewpoint that a "supernatural being created humankind," a doctrine central to the dogmas of certain religious denominations. Third, the law significantly entangled the interests of church and state by seeking "the symbolic and financial support of government to achieve a religious purpose." 71. Brandeis brief: A brief with relevant facts for a case. First used in Muller v. Hogan in regards to women’s work hours. 72. New York City Bar Ass’n 73. Jehovah’s Witnesses- (restorationist Christian denomination -- distinct from mainstream christianity) Their beliefs are based on their interpretation of the bible and they prefer to use their own translation-- Numerous cases involving Jehovah’s witnesses have been heard revolving around 3 subjects-- practice of their religion, displays of patriotism and military service, and blood transfusions 74. ACLU- AMERICAN CIVIL LIBERTIES UNION 75. NAACP- NATIONAL ASSOCIATION FOR THE ADVANCEMENT OF COLORED PEOPLE