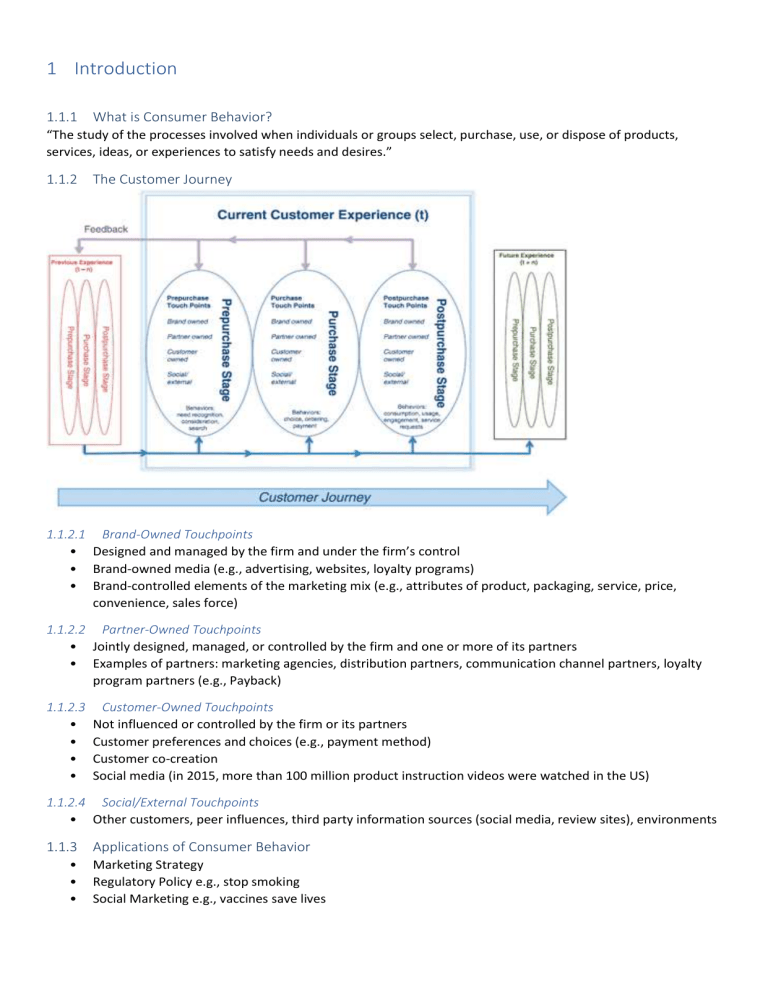

1 Introduction 1.1.1 What is Consumer Behavior? “The study of the processes involved when individuals or groups select, purchase, use, or dispose of products, services, ideas, or experiences to satisfy needs and desires.” 1.1.2 The Customer Journey 1.1.2.1 Brand-Owned Touchpoints • Designed and managed by the firm and under the firm’s control • Brand-owned media (e.g., advertising, websites, loyalty programs) • Brand-controlled elements of the marketing mix (e.g., attributes of product, packaging, service, price, convenience, sales force) 1.1.2.2 Partner-Owned Touchpoints • Jointly designed, managed, or controlled by the firm and one or more of its partners • Examples of partners: marketing agencies, distribution partners, communication channel partners, loyalty program partners (e.g., Payback) 1.1.2.3 • • • • Customer-Owned Touchpoints Not influenced or controlled by the firm or its partners Customer preferences and choices (e.g., payment method) Customer co-creation Social media (in 2015, more than 100 million product instruction videos were watched in the US) 1.1.2.4 Social/External Touchpoints • Other customers, peer influences, third party information sources (social media, review sites), environments 1.1.3 Applications of Consumer Behavior • • • Marketing Strategy Regulatory Policy e.g., stop smoking Social Marketing e.g., vaccines save lives 1.1.4 Marketing Strategy and Consumer Behavior Consumer Decision Process Market segmentation Market Analysis Problem recognition Identify productrelated need sets Marketing Strategy Information search Conditions Group customes with similar need sets Alternative evaluation Consumers Describe each group Product, Price, Distribution, Promotion, Service Company Competitors Outcomes Individual Firm Social Purchase Select attractive segment(s) to target Use Evaluation 1.1.4.1 Market Analysis Company Recognizing firms’ (marketing) abilities (strength/ weaknesses), including NPD, channel, advertising, service, research, consumer knowledge, … Competitors Knowledge of competitors’ capabilities and strategies Conditions State of economy, physical environment, government regulations, technological developments Consumers Knowledge of consumers’ needs and desires and anticipate their reactions 1.1.4.2 Market Segmentation Market segmentation involves four steps: 1. 2. 3. 4. Identifying product-related need sets. Grouping customers with similar need sets. Describing each group. Selecting an attractive segment(s) to serve. A market segment is a portion of a larger market whose needs differ somewhat from the larger market. Since a market segment has unique needs, a fi rm that develops a total product focused solely on the needs of that segment will be able to meet the segment’s desires better than a firm whose product or service attempts to meet the needs of multiple segments. 1.1.4.3 Marketing Strategy Marketing strategy is basically the answer to the question, How will we provide superior customer value to our target market? The answer to this question requires the formulation of a consistent marketing mix. The marketing mix is the product, price, communications, distribution, and services provided to the target market. It is the combination of these elements that meets customer needs and provides customer value. Product Consumers buy need satisfaction, not a physical product Price Consumer cost: everything a consumer must surrender to receive the benefits of owning/using a product Communication With whom? What? Where? When? What effect? Distribution How? Where? When? Service Auxiliary or peripheral activities that are performed to enhance the primary product 1.1.4.4 Consumer Decision Process Need Recognition Information Search Evaluate Alternatives Purchase Decision 1.1.4.5 Outcomes Firm outcomes Product/Brand position Sales and profits Customer satisfaction Post-purchase Evaluation Individual outcomes Need satisfaction Injurious consumption Society outcomes Economic Physical environment social welfare 1. Firm outcome: a. Product position: Is the most basic outcome of a firms marketing strategy. Meaning the image or concept of the product in any form which does not require purchase or use for it to develop. It is determined by various forms of communication by the brand and other sources. Most marketing firms prefer to measure their product position on a regular basis because a brand whose position matches matches the desired position of a market it is more likely to be purchased. b. Sales and profits: A critical outcome, in terms of sales revenues and profits firms virtually evaluate the success of their marketing strategies and if the initial consumer analysis is correct and marketing mix matches the consumer decision process results in sales and profit. c. Customer Satisfaction: Retaining customers by ensuring satisfactory purchases than making new ones is more profitable. Initial sale is made by convincing customers that the firms offer is of superior value. It is important to offer more than the customers expectations to make them loyal to your firm and it requires immense understanding of consumer behavior. 2. Individual outcome: Whether a purchase is made or not, a level of satisfaction of the need that initiated the consumption process is necessary. Customer satisfaction can be achieved by balancing between the actual need fulfillment and the perceived need fulfillment. However, at times they differ. For example, people might take food supplements because they believe the supplements are enhancing their health while, they could have no direct health effects or even negative effects. One objective of government regulation and a frequent goal of consumer groups is to ensure that consumers can adequately judge the extent to which products are meeting their needs. a. Injurious consumption occurs when the consumption can result in negative effects on the wellbeing of a person. 3. Society outcome: Society outcomes have three phases, Economic outcomes, Physical environment outcome and social welfare. a. Economic Outcome: The state of a given country’s economy basically depends on the overall consumer's purchase decision including the decision of not buying something. Consumers’ decisions on whether to buy or to save affect economic growth, the availability and cost of capital, employment levels, and so forth. The types of products and brands purchased influence the balance of payments, industry growth rates, and wage levels. Decisions made in one society, particularly large, wealthy societies such as those of the United States, Western Europe, and Japan, have a major impact on the eco- nomic health of many other countries. b. Physical Environment outcomes: The cumulative impact of consumer decision has impact on its own and other societies as well. E.g., The decision of consuming meat as a primary source of protein in most developed or developing countries results in the clearing of rainforests for grazing land, the pollution of many watersheds due to large-scale feedlots, and an inefficient use of grain, water, and energy to produce protein. c. Social Welfare: The cumulative impact of consumer decisions also hampers social welfare to a great extent. E.g., Injurious consumption such as cigarettes, alcohol, and drugs and so many more has a great social cost. Also, the impact of private goods (personal purchases) representatives d. However, the same authors conclude: “Although these problems appear daunting, they are all problems that are solvable through altruistic [social] marketing.” Thus, marketing and consumer behavior can both aggravate and reduce serious social problems. 1.1.5 Consumer Research The fields closer to the top of the pyramid concentrate on the individual consumer (micro issues), and those toward the base are more interested in the collective activities that occur among larger groups of people, such as consumption patterns members of a culture or subculture share (macro issues). You can find people with training in a wide range of disciplines—from psychophysiology to literature—doing consumer research. Universities, manufacturers, museums, advertising agencies, and governments employ consumer researchers. 1.2 Now you know 1. 2. 3. 4. what consumer behavior is how consumer behavior shapes marketing strategy the scientific disciplines that study consumer behavior consumer trends to look out for 1.3 Science Insight Barasch, A., Zauberman, G., & Diehl, K. (2018). How the intention to share can undermine enjoyment: Photo-taking goals and evaluation of experiences. Journal of Consumer Research, 44(6), 1220-1237. https://doi.org/10.1093/jcr/ucx112 1.3.1 Abstract People often share their experiences with others who were not originally present, which provides them with both personal and interpersonal benefits. However, most prior work on this form of sharing has examined the decision to share one’s experience only after the experience is over. We investigate a distinct, unexplored aspect of the sharing process: when the decision to share is already salient during an experience and hence can impact the experience itself. We examine this research question within the context of photo-taking, an increasingly ubiquitous and integral part of people’s experiences. Across two field and three laboratory studies, we find that relative to taking pictures for oneself (e.g., to preserve one’s memories), taking pictures with the intention to share them with others (e.g., to post on social media) reduces enjoyment of experiences. This effect occurs because taking photos with the intention to share increases self-presentational concern during the experience, which can reduce enjoyment directly, as well as indirectly by lowering engagement with the experience. We identify several factors that moderate the effect of photo-taking goals on enjoyment, such as individual differences in the extent to which individuals care about how others perceive them and the closeness of the intended audience. 2 Consumer wellbeing 2.1.1 Business Ethics and Consumer Rights • The majority of consumers around the world say they are willing to pay more for products and services from companies that are committed to positive social and environmental impact. Younger consumers express this • • • preference even more strongly: About 3/4 of them feel this way, and 81% of them even expect their favorite companies to declare publicly what they are doing to make the world a better place. Business ethics are rules of conduct that guide actions in the marketplace; these are the standards against which most people in a culture judge what is right and what is wrong, good, or bad. Because each culture has its own set of values, beliefs, and customs, companies around the world define ethical business behaviors quite differently. Regardless of whether they do it intentionally, some marketers do violate their bonds of trust with consumers Business ethics are rules of conduct that guide actions in the marketplace; these are the standards against which most people in a culture judge what is right and what is wrong, good or bad. Because each culture has its own set of values, beliefs, and customs, companies around the world define ethical business behaviors quite differently. 2.1.2 Manipulative Marketing Allegation Allegation: The marketing system creates artificial needs—demand that only its products can satisfy! Response Response: Needs are biological motives and are thus already there. Marketing recommends easy to satisfy these needs Allegation: Marketing manipulates the masses by making promises products cannot meet. Response: Marketing helps to communicate the availability of products than can satisfy existing needs, thereby reducing consumers’ search costs. 2.1.3 Consumer Rights Dissatisfied consumers… • • • appeal directly to the seller for redress (e.g., refund) engage in negative word-of-mouth and boycott include third parties Kennedy’s Declaration of Consumer Rights” (1962) Consumers have the right to… • • • • • • • • the satisfaction of basic needs be protected against hazardous products have the facts needed to make an informed decision choose between a variety of products and services be heard in making and execution of government policy a fair settlement of justice claims acquire the skills and knowledge to be an informed and responsible consumer to live in a healthy and sustainable environment 2.1.4 Market Access For many consumers, the ability to have access (find and purchase) goods and services is limited because of physical, mental, economic, or social barriers. • • • Disabilities o There are 54 million adults with disabilities who spend almost $200 billion annually, yet companies pay remarkably little attention to the unique needs of this vast group. Fully 11 million U.S. adults have a condition that makes it difficult for them to leave home to shop, so they rely almost exclusively on catalogs and the internet to purchase products. Food deserts o Department of Agriculture defines a food desert as a census tract where 33 percent of the population or 500 people, whichever is less, live more than a mile from a grocery store in an urban area or more than 10 miles away in a rural area. Healthy food options in these communities are hard to find or are unaffordable. Media literacy o refers to a consumer’s ability to access, analyze, evaluate, and communicate information in a variety of forms, including print and nonprint messages. It empowers people to be both critical thinkers and creative producers of an increasingly wide range of messages using image, language, and sound. 2.1.5 Dark Consumer Behavior • • • • Addictive Consumption o Consumer addiction is a physiological or psychological dependency on products or services. Many companies profit from selling addictive products or from selling solutions for kicking a bad habit. (Social) Media Addiction o Psychologists compare social media addiction to chemical dependency, to the point of inducing symptoms of withdrawal when users are deprived of their fix. As one noted, “Everyone is a potential addict—they’re just waiting for their drug of choice to come along, whether heroin, running, junk food, or social media.” Compulsive consumption o Compulsive consumption refers to repetitive and often excessive shopping performed as an antidote to tension, anxiety, depression, or boredom Consumed consumers o People who are used or exploited, willingly or not, for commercial gain in the marketplace. E.g., prostitutes, organ blood or hard donors, babies for sale 2.2 Now you know • • • what ethical business is o that consumers have the right for safe and functional products that consumer behavior can harm themselves, other individuals, and society 2.3 Science Insight Mogilner, C. (2010). The pursuit of happiness: Time, money, and social connection. Psychological Science, 21(9), 1348-1354. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797610380696 2.3.1 Abstract Does thinking about time, rather than money, influence how effectively individuals pursue personal happiness? Laboratory and field experiments revealed that implicitly activating the construct of time motivates individuals to spend more time with friends and family and less time working behaviors that are associated with greater happiness. In contrast, implicitly activating money motivates individuals to work more and socialize less, which (although productive) does not increase happiness. Implications for the relative roles of time versus money in the pursuit of happiness are discussed. 3 Perception 3.1 The Stages of Perception Figure 1 Figure 3.1 AN OVERVIEW OF THE PERCEPTUAL PROCESS three stages of exposure, attention, and interpretation make up the process of perception. 3.1.1 Exposure Exposure occurs when a stimulus comes within the range of someone’s sensory receptors. Consumers concentrate on some stimuli, are unaware of others, and even go out of their way to ignore some messages. 3.1.2 Attention Attention refers to the extent to which processing activity is devoted to a particular stimulus. As you know from sitting through both interesting and “less interesting” lectures, this allocation can vary depending on both the characteristics of the stimulus (i.e., the lecture itself) and the recipient (i.e., your mental state at the time). 3.1.3 Interpretation Interpretation refers to the meanings we assign to sensory stimuli. Just as people differ in terms of the stimuli that they perceive, the meanings we assign to these stimuli vary as well. Many of these meanings depend on our socialization within a society: Even sensory perception is culturally specific. 3.1.4 Vision Hue: the perceptual attribute corresponding to a color’s dominant wavelength in the electromagnetic visible spectrum, resulting in our perceptions of red, green, blue, and so on. Value: the color’s level of darkness, with low value tending toward black. Saturation: the color’s purity, sometimes described as colorfulness relative to brightness. 3.1.5 Scents Odors stir emotions or create a calming feeling. Marketing examples: Consumers who were exposed to chocolaty odors were more likely to try different alternatives Warm scents as opposed to cool scents enhance shoppers’ purchases of premium brands we process fragrances in the limbic system and is one of the most ancient system human brain has→ fragrances are connected to memory 3.1.6 Sound BMW using audio watermark at the end of the ads Consumers are more likely to recognize names that begin with a hard consonant like K (Kellogg’s) or P (Pepsi) sound symbolism: the process by which the way a word sounds influences our assumptions about what it describes and attributes such as size. 3.1.7 Touch Natural User Interface o philosophy of computer design that incorporates habitual human movements Endowment Effect o The mere ownership effect, or the endowment effect, is the tendency of an owner to evaluate an object more favorably than a nonowner. This occurs almost immediately upon acquiring an object and increases with time of ownership. Thus, people tend to value an object more after acquiring it than before. Branding 3.1.8 Taste: Tomato juice is not popular but on airplane 25% of the passengers drink it because exposure to high levels of noise dulls the ability to taste sweet things electronic mouth to test products gastrophysics: the science that focuses on how physics, chemistry, and perception, influence how we experience what we put in our mouths basic taste: sweetness, sourness, bitterness, saltiness, and umami 3.1.9 Exposure It occurs when a stimulus is in the range of our sensory receptors. We may concentrate on some stimuli and ignore others. Stimuli might be above or under a sensory threshold Psychophysics: focuses on how people integrate environment into their personal subjective worlds 3.1.9.1 Sensory Thresholds a stimulus comes within the range of someone’s sensory receptor Absolute threshold: the minimum amount of stimulation a person can detect on a given sensory channel. Differential threshold: the ability of a sensory system to detect changes in or differences between two stimuli 3.1.9.2 Selective exposure The highly selective nature of consumer exposure is a major concern for marketers since failure to gain exposure results in lost communication and sales opportunities. For example, consumers are highly selective in the way they shop once they enter a store 3.1.10 Attention Stimulus Selection Factors • Size o • • • The size of the stimulus itself in contrast to the competition helps to determine if it will command attention. Readership of a magazine ad increases in proportion to the size of the ad Color o As we’ve seen, color is a powerful way to draw attention to a product or to give it a distinct identity. Black & Decker developed a line of tools it called DeWalt to target the residential construction industry. The company colored the new line yellow instead of black; this made the equipment stand out against other “dull” tools Position o we stand a better chance of noticing stimuli that are in places where we’re more likely to look. Novelty o Stimuli that appear in unexpected ways or places tend to grab our attention. 3.1.11 Interpretation 3.1.11.1 Perceptual Relativity it is generally a relative process rather than absolute, often referred to as perceptual relativity. It is often difficult for people to make interpretations in the absence of some reference point. Interpretation tends to be relative rather than absolute (perceptual relativity) and subjective rather than objective. 3.1.11.2 Cognitive Interpretation • The process whereby stimuli are placed into existing categories of meaning. • Cognitive interpretation is a process whereby stimuli are placed into existing categories of meaning. As we saw earlier, ads are categorized as expected or unexpected, a process that can vary by culture and individual. • In countries like France where ads are more sexually explicit, nudity may be seen as more appropriate than in the United States. • Products are also categorized. When DVD players were first introduced, most consumers probably grouped them in the same category as VCRs, but with further experience put them in separate categories. 3.1.11.3 Affective Interpretation • The emotional or feeling response triggered by a stimulus such as an ad. Emotional response can range from positive (upbeat, exciting, warm) to neutral (disinterested) to negative (anger, fear, frustration). • Like cognitive interpretation, there are “normal” (within-culture) emotional responses to many stimuli (e.g., most Americans experience a feeling of warmth when seeing pictures of young children with kittens). • Likewise, there are also individual variations to this response (a person allergic to cats might have a negative emotional response to such a picture). 3.1.11.4 Semiotics • The study of signs and symbols • semiotics, a discipline that studies the correspondence between signs and symbols and their roles in how we assign meanings. Semiotics is a key link to consumer behavior because consumers use products to express their social identities. 3.2 Now you know • • • how products and commercials often (try to) appeal to our senses that perception is a three-stage process that reality (the meaning we assign to sensations) may not be as objective as you might think 3.3 Science Insight Schroll, R., Schnurr, B., & Grewal, D. (2018). Humanizing products with handwritten typefaces. Journal of Consumer Research, 45(3), 648-672. https://doi.org/10.1093/jcr/ucy014 3.3.1 Abstract The loss of a sense of humanness that stems from increasing mechanization, automation, and digitization gives firms an impetus to develop effective ways to humanize products. On the basis of knowledge activation theory, this article systematically investigates a novel humanization approach: the use of typefaces that appear to be handwritten. Across several laboratory and field studies, the authors provide evidence of the positive effect of handwritten typefaces, reveal the mechanisms that lead to these outcomes, and outline some boundary conditions. Specifically, the results show that handwritten typefaces create perceptions of human presence, which lead to more favorable product evaluations (and behavior) by enhancing the emotional attachment between the consumer and the product. However, these effects are mitigated for brands to which consumers already feel a sense of attachment. Finally, the effects reverse when the products are functionally positioned or functional in nature. The present article thus extends understanding of humanization processes and provides guidelines for how and when brands should use handwritten typefaces. Typefaces that appear handwritten are perceives as • • friendly and personal unprofessional and childish that handwritten typeface alters product perception that using handwritten typefaces can enhance product evaluation and purchase that using handwritten typefaces may backfire when products are rather functional in nature 4 Learning & memory 4.1.1 How Do We Learn? • • (Intentional) Learning o is a relatively permanent change in behavior caused by experience. Incidental Learning o we can also learn when we observe events that affect others. We learn even when we don’t try: We recognize many brand names and hum many product jingles, for example, even for products we don’t personally use 4.1.2 Learning Theories 4.1.2.1 Behavioral Learning Theories Behavioral learning theories assume that learning takes place as the result of responses to external events. • Learning takes place as the results of responses to external events • • The mind is a ‘black box’ o Psychologists approach the mind as a “black box” and emphasize the observable aspects of behavior. The observable aspects consist of things that go into the box (the stimuli or events perceived from the outside world) and things that come out of the box (the responses, or reactions to these stimuli). Classical vs. instrumental conditioning o Classical conditioning occurs when a stimulus that elicits a response is paired with another stimulus that initially does not elicit a response on its own. Over time, this second stimulus causes a similar response because we associate it with the first stimulus. Pavlov induced classically conditioned learning when he paired a neutral stimulus (a bell) with a stimulus known to cause a salivation response in dogs (he squirted dried meat powder into their mouths). The powder was an unconditioned stimulus (UCS) because it was naturally capable of causing the response. Over time, the bell became a conditioned stimulus (CS); it did not initially cause salivation, but the dogs learned to associate the bell with the meat powder and began to salivate at the sound of the bell only. The drooling of these canine consumers because of a sound, now linked to feeding time, was a conditioned response (CR). o Family branding Many products capitalize on the reputation of a company name. Companies such as Campbell’s, Heinz, and General Electric rely on their positive corporate images to sell a variety of product lines. Product line extension Marketers add related products to an established brand. Dole, which we associate with fruit, introduced refrigerated juices and juice bars, whereas Sun Maid went from raisins to raisin bread. Licensing Companies often “rent” well-known names, hoping that the learned associations they have forged will “rub off” onto other kinds of products. Zippo Manufacturing Co., long known for its “windproof” cigarette lighters, markets a men’s fragrance. Look-alike packaging Distinctive packaging designs create strong associations with a particular brand. Companies that make generic or private-label brands and want to communicate a quality image often exploit this linkage when they put their products in packages similar to those of popular brands. Instrumental conditioning (or operant conditioning) occurs when we learn to perform behaviors that produce positive outcomes and avoid those that yield negative outcomes. E.g., teaching pigeons and other animals to dance, play Ping-Pong, and perform other activities when he systematically rewarded them for desired behaviors. Shaping We may learn the desired behavior over a period of time as a shaping process rewards our intermediate actions. For example, the owner of a new store may award prizes to shoppers who simply drop in; she hopes that over time they will continue to drop in and eventually even buy something. Gamification turns routine actions into experiences as it adds gaming elements to tasks that might otherwise be boring or routine. Gamification is simply about providing rewards to customers to encourage them to buy even more. 4.1.2.2 Cognitive Learning Theories • Learning is the result of internal mental processing • People actively use information to master the world around them o views people as problem-solvers who actively use information from the world around them to master their environments. • Observational learning & analytical reasoning o Observational learning occurs when we watch the actions of others and note the reinforcements they receive for their behaviors. In these situations, learning occurs because of vicarious rather than direct experience. o o Analytical reasoning occurs when we engage in creative thinking to restructure and recombine existing information to form new associations and concepts. The most complex form of cognitive learning is analytical reasoning. In reasoning, individuals engage in creative thinking to restructure and recombine existing information as well as new information to form new associations and concepts. Information from a credible source that contradicts or challenges one’s existing beliefs will often trigger reasoning. MHK Cognitive learning encompasses all the mental activities of humans as they work to solve problems or cope with situations. Three types of cognitive learning are important to marketers. 1. Iconic Rote Learning. Learning a concept or the association between two or more concepts in the absence of conditioning is known as iconic rote learning. 2. Vicarious Learning or Modeling It is not necessary for consumers to directly experience a reward or punishment to learn. Instead, they can observe the outcomes of others’ behaviors and adjust their own accordingly. 3. Analytical Reasoning The most complex form of cognitive learning is analytical reasoning. In reasoning, individuals engage in creative thinking to restructure and recombine existing information as well as new information to form new associations and concepts. 4.1.3 Learning to Be a Consumer 4.1.3.1 Consumer Socialization Consumer socialization is the process “by which young people acquire skills, knowledge, and attitudes relevant to their functioning in the marketplace.” Research supports the proposition that the brand preferences and product knowledge that occur in childhood persist into the later stages of consumers’ lives. 4.1.4 Strength of Learning • Importance refers to the value that consumers place on the information to be learned. Importance might be driven by inherent interest in the product or brand or might be driven by the need to make a decision in the near future. • • • • Message involvement When a consumer is not motivated to learn the material, processing can be increased by causing the person to become involved with the message itself. Mood Get happy, learn more? Research indicates that this is indeed true. A positive mood during the presentation of information such as brand names enhances learning. Reinforcement Anything that increases the likelihood that a given response will be repeated in the future is considered reinforcement. While learning frequently occurs in the absence of reinforcement, reinforcement has a significant impact on the speed at which learning occurs and the duration of its effect. Repetition enhances learning and memory by increasing the accessibility of information in memory or by strengthening the associative linkages between concepts. Quite simply, the more times people are exposed to information or engage in a behavior, the more likely they are to learn and remember it. 4.1.5 Memory Memory is a process of acquiring information and storing it over time so that it will be available when we need it. • • • • Sensory memory stores the information we receive from our senses. This storage is temporary; it lasts a couple of seconds at most. For example, a man who walks past a donut shop gets a quick, enticing whiff of something baking inside. Short-term memory (STM) also stores information for a limited period of time, and it has limited capacity. Similar to a computer, this system is working memory; it holds the information we are currently processing. A cognitive process of elaborative rehearsal allows information to move from STM into LTM. This involves thinking about the meaning of a stimulus and relating it to other information already in memory. Marketers assist in the process when they devise catchy slogans or jingles that consumer repeat on their own. Long-term memory (LTM) is the system that allows us to retain information for a long period of time. 4.1.5.1 Long-term memory Schemas Both concepts and episodes acquire depth of meaning by becoming associated with other concepts and episodes. A pattern of such associations around a particular concept is termed a schema or schematic memory, sometimes called a knowledge structure. Scripts Memory of how an action sequence should occur, such as purchasing and drinking a soft drink to relieve thirst, is a special type of schema known as a script 4.1.6 Information Storing 4.1.6.1 Associative Networks According to activation models of memory, an incoming piece of information gets stored in an associative network that contains many bits of related information. We each have organized systems of concepts that relate to brands, manufacturers, and stores stored in our memories; the contents, of course, depend on our own unique experiences. 4.1.6.2 Spreading Activation This process of spreading activation allows us to shift back and forth among levels of meaning. The way we store a piece of information in memory depends on the type of meaning we initially assign to it. • • • • • Brand specific - Memory is stored in terms of claims the brand makes (it’s macho) Ad-specific - Memory is stored in terms of the medium or content of the ad itself (sexist appeals) Brand identification - Memory is stored in terms of the brand name (Axe) Product category - Memory is stored in terms of how the product works or where it should be used (makes me more attractive) Evaluative reaction - Memory is stored as positive or negative emotions (looks cool) 4.1.7 Forgetting 4.1.7.1 Decay The structural changes that learning produces in the brain simply go away. In a process of decay, the structural changes that learning produces in the brain simply go away 4.1.7.2 interference Forgetting also occurs as a result of interference; as we learn additional information, it displaces the previous information. Consumers may forget stimulus–response associations if they subsequently learn new responses to the same or similar stimuli; we call this process retroactive interference. Or prior learning can interfere with new learning, a process we term proactive interference. 4.1.7.3 State-Dependent-Retrieval The phenomenon of state-dependent retrieval illustrates that we are better able to access information if our internal state is the same at the time of recall as when we learned the information. So, we are more likely to recall an ad if our mood or level of arousal at the time of exposure is similar to that in the purchase environment. 4.1.7.4 von Restorff Effect The von Restorff Effect is well-known to memory researchers; it shows that almost any technique that increases the novelty of a stimulus also improves recall. This explains why unusual advertising or distinctive packaging tends to facilitate brand recall. 4.1.8 BRAND IMAGE AND PRODUCT POSITIONING 4.1.8.1 Brand Image Brand image refers to the schematic memory of a brand. It contains the target market’s interpretation of the product’s attributes, benefits, usage situations, users, and manufacturer/ marketer characteristics. It is what people think of and feel when they hear or see a brand name. It is, in essence, the set of associations consumers have learned about the brand. Company image and store image are similar except that they apply to companies and stores rather than brands 4.2 Now you know • • • • that conditioning results in learning that we learn about products by observing others’ behavior that our brains store information in various ways that we will not retrieve everything we have stored in memory 4.3 Science Insight Patrick, V. M., Atefi, Y., & Hagtvedt, H. (2017). The allure of the hidden: How product unveiling confers value. International Journal of Research in Marketing, 34(2), 430-441 10.1016/j.ijresmar.2016.08.009 4.3.1 Abstract Different package designs call for different ways of revealing the product. In this research, we demonstrate that packaging that calls for unveiling—the removal of the cover of a concealed, stationary object—enhances the perceived value of the product compared to other forms of product revelation. Drawing on theories of grounded associations, shared meaning, and contagion, we theorize that the act of unveiling is associated with revealing a protected and thus pristine object, which is consequently perceived to be valuable. We begin the empirical investigation by exploring consumer associations with product unveiling across American and South Korean consumers (pilot study 1). We then demonstrate that the unveiling effect arises with both imagined (pilot study 2) and real objects and is mediated by beliefs about the pristine condition of the object (studies 1–3). We conclude with a discussion of the theoretical contributions, implications for managers, and directions for future research. 4.3.2 Implications • • • A package designed to unveil an object must meet two key criteria: (a) the product must be concealed within a protective package, connoting its pristine nature, and (b) should remain stationary within the packaging when the cover is removed to reveal the product. Contrasting unveiling with other forms of product revelation: unveiling has a favorable influence on a product's perceived value and beliefs about the pristine nature of the product mediate the unveiling effect. Extends the notion of contagion to the visual domain. 4.3.3 Now, You Know… • • • that learned associations impact how we evaluate products that are packaged a certain way how marketers and designers might use this knowledge to drive perceptions of product value that people feel products to be contaminated even when products are merely looked at by others 5 Motivation Motivation is the reason for behavior (why we do what we do) Motivation refers to the processes that lead people to behave as they do. It occurs when a need that the consumer wishes to satisfy is aroused. The need creates a state of tension that drives the consumer to attempt to reduce or eliminate it. This need may be utilitarian (i.e., a desire to achieve some functional or practical benefit, as when a person loads up on green vegetables for nutritional reasons) or it may be hedonic (i.e., an experiential need, involving emotional responses or fantasies as when a person feels “righteous” by eating kale). The desired end state is the consumer’s goal. Marketers try to create products and services to provide the desired benefits and help the consumer to reduce this tension. 5.1.1 Motivational Strength 5.1.1.1 Drive Theory • Biological needs cerate an unpleasant state of arousal • Homeostasis: balanced state (stability) within the biological system • Retail therapy: shopping can restore a sense of personal control over one’s environment 5.1.1.2 Expectancy Theory Expectancy theory suggests that expectations of achieving desirable outcomes—positive incentives—rather than being pushed from within motivate our behavior. We choose one product over another because we expect this choice to have more positive consequences for us. Thus, we use the term drive here loosely to refer to both physical and cognitive processes. • • Expectations of achieving a desirable outcome motivate behavior o Expectancy theory suggests that expectations of achieving desirable outcomes—positive incentives—rather than being pushed from within motivate our behavior. We choose one product over another because we expect this choice to have more positive consequences for us. Thus, we use the term drive here loosely to refer to both physical and cognitive processes. Placebo effect: tendency of the brain to convince you that a fake treatment is real o The placebo effect vividly demonstrates the role that expectations play on our feelings, thoughts, and behaviors. This term refers to the well-documented tendency for your brain to convince you that a fake treatment is the real thing—and thus a sugar pill or other placebo can reduce pain, treat insomnia, and provide other benefits. 5.1.2 Motivational Direction a need reflects a basic goal such as keeping yourself nourished or protected from the elements. In contrast a want is a specific pathway to achieving this objective that depends a lot on our unique personalities, cultural upbringing, and our observations about how others we know satisfy the same need. Needs 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. Necessities/essentials Essential for survival Do not change over time Non-fulfillment can lead to adverse outcomes Same across people Differ between people Clothing, shelter, medicine, food, education, social contact Wants 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. Desires Not essential for survival Change over time Non-fulfilment may result in mental distress Fancy suit, leather shoes, pool, television, Ferrari, home décor 5.1.3 Motivational Conflict • • • A person has an approach–approach conflict when he or she must choose between two desirable alternatives. A student might be torn between going home for the holidays and going on a skiing trip with friends. Or he or she might have to choose between going to listen to two bands that are playing at different clubs on the opposite sides of town. o The theory of cognitive dissonance is based on the premise that people have a need for order and consistency in their lives and that a state of dissonance (tension) exists when beliefs or behaviors conflict with one another. We resolve the conflict that arises when we choose between two alternatives through a process of cognitive dissonance reduction, where we look for a way to reduce this inconsistency (or dissonance) and thus eliminate unpleasant tension. An approach–avoidance conflict occurs when we desire a goal but wish to avoid it at the same time. Some solutions to these conflicts include the proliferation of fake furs, which eliminate guilt about harming animals to make a fashion statement, and the success of diet programs such as Weight watchers that promise good food without the calories. Many marketers try to help consumers overcome guilt by convincing them that they deserve these luxuries. Sometimes we find ourselves caught “between a rock and a hard place.” We may face a choice with two undesirable alternatives: for instance, the option of either spending more money on an old car or buying a new one. Don’t you hate when that happens? Marketers frequently address an avoidance–avoidance conflict with messages that stress the unforeseen benefits of choosing one option (e.g., when they emphasize special credit plans to ease the pain of car payments). 5.2 Consumer Needs 5.2.1 Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs Figure 2 MASLOW’S HIERARCHY OF NEEDS Maslow’s hierarchy of needs is based on four premises: 1. 2. 3. 4. All humans acquire a similar set of motives through genetic endowment and social interaction. Some motives are more basic or critical than others. The more basic motives must be satisfied to a minimum level before other motives are activated. As the basic motives become satisfied, more advanced motives come into play. Example: • • • • • Physiological— “I eat what I grow.” Safety— “I feel safe in the garden.” Social— “I can share my produce with others.” Esteem— “I can create something of beauty.” Self-actualization— “My garden gives me a sense of peace.” 5.2.2 McGuire’s Psychological Motives Classification system that organizes theories of motives into 16 categories: 1. Cognitive or affective mode of motivation o Cognitive motives focus on the person’s need for being adaptively oriented toward the environment and achieving a sense of meaning. o Affective motives deal with the need to reach satisfying feeling states and to obtain personal goals 2. Focused on preservation of the status quo or on growth o Preservation-oriented motives emphasize the individual as striving to maintain equilibrium, o while growth motives emphasize development. 3. Behavior actively initiated or in response to the environment (passive) o distinguishes between motives that are actively or internally aroused versus those that are a more passive response to circumstances 4. Behavior helps achieve a new internal or external relationship to the environment o used to categorize outcomes that are internal to the individual and those focused on a relationship with the environment. Internal Cognitive Preservation motive Active Need for consistency A basic desire is to have all facets of oneself consistent with each other. External 5.2.2.1 Need for attribution This set of motives deals with our need to determine who or what causes the things that happen to us and relates to an area of research called attribution theory. External Internal 5.2.2.2 Need for autonomy The need for independence and individuality is a characteristic of the American culture. All individuals in all cultures have this need at some level. Need for stimulation People often seek variety and difference out of a need for stimulation. Internal Affective Preservation motives Active Need for Tension Reduction People encounter situations in their daily lives that create uncomfortable levels of stress. To effectively manage tension and stress, people are motivated to seek ways to reduce arousal. External 5.2.2.3 Cognitive Growth motives Active Need for Expression This motive deals with the need to express one’s identity to others. People feel the need to let others know who and what they are by their actions, which include the purchase and use of goods. 5.2.2.4 Affective Growth motives Active Passive Need to categorize People have a need to categorize and organize the vast array of information and experiences they encounter in a meaningful yet manageable way. So they establish categories or mental partitions to help them do so. Need for objectification These motives reflect needs for observable cues or symbols that enable people to infer what they feel and know. Passive Teleological need Consumers are pattern matchers who have images of desired outcomes or end states with which they compare their current situation. Behaviors are changed and the results are monitored in terms of movement toward the desired end state. This motive propels people to prefer mass media such as movies, television programs, and books with outcomes that match their view of how the world should work (e.g., the good guys win). Utilitarian need These theories view the consumer as a problem solver who approaches situations as opportunities to acquire useful information or new skills. Thus, a consumer watching a situation comedy on television not only is being entertained but is learning clothing styles, lifestyle options, and so forth. Passive Need for Ego Defense The need to defend one’s identity or ego is another important motive. When one’s identity is threatened, the person is motivated to protect his or her self-concept and utilize defensive behaviors and attitudes. Need for Reinforcement People are often motivated to act in certain ways because they were rewarded for behaving that way in similar situations in the past. This is the basis for operant learning. Passive Internal Need for assertion Many people are competitive achievers who seek success, admiration, and dominance. Important to them are power, accomplishment, and esteem. External Need for Affiliation Affiliation refers to the need to develop mutually helpful and satisfying relationships with others. It relates to altruism and seeking acceptance and affection in interpersonal relations. Need for Identification The need for identification results in the consumer’s playing various roles. A person may play the role of college student, sorority member, bookstore employee, fiancée, and many others. One gains pleasure from adding new, satisfying roles and by increasing the significance of roles already adopted. Need for Modeling The need for modeling reflects a tendency to base behavior on that of others. Modeling is a major means by which children learn to become consumers. 5.3 Purchase Motives Motives that are known and freely admitted are called manifest motives. motives that conform to a society’s prevailing value system are more likely to be manifest than are those in conflict with such values. Latent motives described above either were unknown to the consumer or were such that she was reluctant to admit them. 5.4 Involvement Involvement is “a person’s perceived relevance of the object based on their inherent needs, values, and interests.” Figure 3 CONCEPTUALIZING INVOLVEMENT Figure 5.3 illustrates that different factors may create involvement. These factors can be something about the person, something about the object, or something about the situation. 5.4.1 Increasing Product Involvement Mass Customization: the personalization of products and services for individual customers at a massproduction price. DIY: When we have the opportunity to personalize a product, our involvement increases because the item reflects our unique preferences. Co-Creation: the company works jointly with customers to create value. This approach is catching on in B2B environments, where organizations partner with their biggest clients to envision new solutions to their problems. Gamification: the application of gaming principles to non-gaming contexts. This approach offers a way to dramatically increase involvement, especially for activities that can benefit from a bit of motivation. 5.4.2 Increasing Message Involvement A marketer can boost a person’s motivation to process relevant information via one or more of the following techniques: Prominent Stimuli: such as loud music and fast action, to capture attention. In print formats, larger ads increase attention. Also, viewers look longer at colored pictures than at black-and-white ones. Celebrity Endorsers: people process more information when it comes from someone they admire or at least know about, whether Michael Jordan, Bill Gates, or maybe even Kim Kardashian. New Media: Invent new media platforms to grab attention. Procter & Gamble printed trivia questions and answers on its Pringles snack chips with ink made of blue or red food coloring. Provide value: Provide value that customers appreciate. Charmin bathroom tissue set up public toilets in Times Square that hordes of grateful visitors used. 5.4.3 Increasing Situational Involvement Situational involvement describes engagement with a store, website, or a location where people consume a product or service. Many retailers and event planners today focus on enhancing customers’ experiences in stores, dealerships, and stadiums. Industry insiders refer to this as a “butts-in-seats” strategy. Personalization: retailers can personalize the messages shoppers receive at the time of purchase. For example, a few marketers tailor the recommendations they give shoppers in a store based on what they picked up from a shelf. High-Tech: Exciting new technologies such as augmented reality, virtual reality, and beacons allow retailers to turn the shopping experience into an adventure. Subscription Boxes: Subscription company websites attract about 37 million visitors a year, and that number has grown by over 800% in just three years. 5.5 Now you know what motivation is that products (and services) can satisfy a range of different consumer needs that the way we evaluate and choose products depends on our degree of involvement with the product, the marketing message, or the purchase situation strategies that can help you change your behavior 5.6 Science Insight Norton, M. I., Mochon, D., & Ariely, D. (2012). The IKEA effect: When labor leads to love. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 22(3), 453-460. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1016/j.jcps.2011.08.002 5.6.1 Abstract In four studies in which consumers assembled IKEA boxes, folded origami, and built sets of Legos, we demonstrate and investigate boundary conditions for the IKEA effect—the increase in valuation of self-made products. Participants saw their amateurish creations as similar in value to experts' creations and expected others to share their opinions. We show that labor leads to love only when labor results in successful completion of tasks; when participants built and then destroyed their creations, or failed to complete them, the IKEA effect dissipated. Finally, we show that labor increases valuation for both “do-it-yourselfers” and novices. (PsycINFO Database Record (c) 2018 APA, all rights reserved) 5.6.2 Implications Likely underlying process: effort, sense of accomplishment Consumer Involvement: companies actively involve consumers in the design, marketing and testing of products Motivation of employees: motivational benefits of assigning employees to tasks they feel capable of completing 5.6.3 Now, You Know… that labor can-–paradoxically—lead to love why it can make sense for companies to have their customers work for them 6 Self-concept 6.1 The Self The independent self-concept emphasizes personal goals, characteristics, achievements, and desires. Individuals with an independent self-concept tend to be individualistic, egocentric, autonomous, self-reliant, and self-contained. They define themselves in terms of what they have done, what they have, and their personal characteristics. The interdependent self-concept emphasizes family, cultural, professional, and social relationships. Individuals with an interdependent self-concept tend to be obedient, sociocentric, holistic, connected, and relation oriented. They defi ne themselves in terms of social roles, family relationships, and commonalities with other members of their groups. Independent Self-Concept Individualistic Egocentric Autonomous Self-reliant Interdependent Self-Concept Obedient Sociocentric Holistic Connected Self-contained Relation-oriented 6.1.1 Self-concept summarizes the beliefs a person holds about his own attributes and how he evaluates the self on these qualities. Dimensions of Self-Concept Private self Social self Actual Self-Concept How I actually see myself How others actually see me Ideal Self-Concept How I would like to see myself How I would like others to see me The self-concept can be divided into four basic parts, as shown in Table 12–1 : actual versus ideal, and private versus social. 1. The actual–ideal distinction refers to the individual’s perception of who I am now (actual self-concept) and who I would like to be (ideal self-concept). 2. The private self refers to how I am or would like to be to myself (private self-concept), and the social self is how I am seen by others or how I would like to be seen by others (social self-concept). 6.1.2 Using Self-Concept to Position Products People’s attempts to obtain their ideal self-concept, or maintain their actual self-concept, often involve the purchase and consumption of products, services, and media. Figure 4 The Relationship between Self-Concept and Brand Image Influence 6.1.3 The Extended Self many of the props and settings consumers use to define their social roles become parts of their selves. Those external objects that we consider a part of us constitute the extended self. In some cultures, people literally incorporate objects into the self: they lick new possessions, take the names of conquered enemies (or in some cases eat them), or bury the dead with their possessions. Extended Self = The Self + Possessions Individual Family Community Group Embodied cognition: states of the body modify states of the mind. our behaviors and observations of what we do and buy shape our thoughts rather than vice versa. One of the most powerful examples is the idea that our body language actually changes how we see ourselves. Wearable computing: Whether devices we wear on our wrist like the Apple Watch, or woven into our clothing, increasingly our digital interactions will become attached to our bodies—and perhaps even inserted into our bodies as companies offer ways to implant computer chips into our wrists. 6.1.4 Self-Esteem Self-esteem refers to the positivity of a person’s self-concept. People with low self-esteem expect that they will not perform very well, and they will try to avoid embarrassment, failure, and rejection. 6.1.4.1 Social Comparison Theory (Festinger 1954) Upward (You > Me) Downward (You < Me) Positive effects Inspiration, Motivation, Hope Gratitide Negative effects Envy, Dissatisfaction, Self-criticism Scorn, Pity How do marketers influence self-esteem? Exposure to ads such as the ones Lisa checked out can trigger a process of social comparison, in which the person tries to evaluate her appearance by comparing it to the people depicted in these artificial images. 6.1.5 The Body as Product Body image refers to consumers’ subjective evaluations of their physical self. Body image refers to a consumer’s subjective evaluation of his or her physical self. Our evaluations don’t necessarily correspond to what those around us see. A man may think of himself as being more muscular than he really is, or a woman may feel she appears fatter than is actually the case. 6.1.6 Ideals of Beauty • • • • • • Physical features (Attractive faces, good health and youth, balance/symmetry, feminine curves/hourglass body shape, “strong” male features) Clothing styles Cosmetics Hairstyles Skin tone Body type Our desires to match up to these ideals—for better or worse—drive a lot of our purchase decisions. 6.1.7 Body Decoration and Mutilation • • • • • • • Separate group members from non-members Place the individual in the social organization Place the person in a gender category Enhance sex-role identification Indicate desired social conduct Indicate high status or rank Provide a sense of security 6.2 Now you know • • • that the self-concept strongly influences consumer behavior that marketing/advertising can distort our self-concept (but also help to maintain it) that the way we think about our bodies (and the way our culture tells us we should think) is a key component of self-esteem 6.3 Science Insight Leung, E., Paolacci, G., & Puntoni, S. (2018). Man versus machine: Resisting automation in identity-based consumer behavior. Journal of Marketing Research, 55(6), 818-831. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0022243718818423 6.3.1 Abstract Automation is transforming many consumption domains, including everyday activities such as cooking or driving, as well as recreational activities like fishing or cycling. Yet little research in marketing examines consumer preferences for automated products. Automation often provides obvious consumption benefits, but six studies spanning a variety of product categories show that automation may not be desirable when identity motives are important drivers of consumption. Using both correlational and experimental designs, these studies demonstrate that people who strongly identify with a particular social category resist automated features that hinder the attribution of identity-relevant consumption outcomes to themselves. The findings have substantial theoretical implications for research on identity and technology, as well as managerial implications for targeting, product innovation, and communication. 6.3.2 Implications For theory • • Automation may increase the outcome utility of a product but decrease its self-signaling utility (Bodner and Prelec 2003), which is particularly relevant for identity-motivated consumers. Action-oriented perspective (Oyserman 2009b) highlighting that identity-based consumption relies on consumers being able to attribute the consumption outcomes to their own skills. For Practice • • • Targeting: risk of targeting strong identifiers with product innovations that involve the automation of identity-relevant tasks Product innovation: which tasks are good candidates for being automated Communication: automated products are not always preferable relative to their nonautomated counterparts 7 Personality 7.1 Freudian Systems ID: The id is about immediate gratification; it is the “party animal” of the mind. It operates according to the pleasure principle; that is, our basic desire to maximize pleasure and avoid pain guides our behavior. The id is selfish and illogical. It directs a person’s psychic energy toward pleasurable acts without any regard for consequences. Superego: The superego is the counterweight to the id. This system is essentially the person’s conscience. It internalizes society’s rules (especially as parents teach them to us) and tries to prevent the id from seeking selfish gratification. Ego: the ego is the system that mediates between the id and the superego. It’s basically a referee in the fight between temptation and virtue. The ego tries to balance these opposing forces according to the reality principle, which means it finds ways to gratify the id that the outside world will find acceptable. (Hint: This is where Freudian theory primarily applies to marketing.) 7.2 The Big Five Personality Traits most widely recognized approach to measuring personality traits is the socalled Big Five (also known as the Neo-Personality Inventory). Description Openness to experience Conscientiousness Extroversion Agreeableness Neuroticism (emotional instability) The degree to which a person is open to new ways of doing things The level of organization and structure a person needs How well a person tolerates stimulation from people The degree to which we defer to other people How well a person copes with stress Example of Measurement Items (agree/disagree) Love to think up new ways of doing things Am always prepared Talk to a lot of different people at parties Take time out for others Get upset easily 7.2.1 Traits and Consumer Behavior The Influence of Personality Traits on Consumer Behavior: Superstition: Sports fan behavior such as “lucky socks,” the direction of one’s cap on the head, purchase of good luck charms, refusal to purchase particular items because of bad luck (e.g., opals, peacock feathers, apricots) Romanticism: Movie genre choice, more likely to take risks, prefer warm countries to visit, prefer luxury travel. Need for control: The need to personally exert control over one’s surrounding environment and life outcomes acts as a barrier to new product acceptance. But framing new products as potentially enhancing one’s sense of control increases acceptance of new products by those high in desire for control. Need for Uniqueness: People who want to “stand out from the crowd” tend to be opinion leaders; they are more likely to be sources of information about brands and products for other people. Extroversion: Extroverts experience more positive emotions when consuming. Agreeableness: The degree to which we defer to other people 7.2.2 Brand Personality Brand personality is a set of human characteristics that become associated with a brand. Consumers perceive brand personalities in terms of five basic dimensions, each with several facets Figure 5 Dimensions of Brand Personality 7.2.3 Brand Resonance Marketers who can create brand resonance cement a bond with the consumer that is very difficult to break.34 This occurs when a brand truly speaks to some aspect of a consumer’s individual life or the culture in which he or she lives. Resonance Type Interdependency Intimacy Personal co-creation Emotional vibrancy Currency value Role resonance Category resonance Impact Facilitates habits, rituals, and routines that entwine the brand’s meanings seamlessly into the consumer’s everyday life Has “insiders” who know details of its history, including significant product development particulars, myths about product creators, and obscure “brand trivia” or facts Encourages consumers to create their own stories about it and how it impacted their lives Elicits strong emotional reactions such as happiness or excitement Evokes a “hot” meaning that defines a major trend in popular culture Emblematic of a social role A benchmark customers use to evaluate other brands Brand Example Starbucks Nike Air Jordan Levi Strauss 501s Disney Uber Birkenstocks Harley-Davidson 7.2.4 Lifestyle A lifestyle defines a pattern of consumption that reflects a person’s choices of how to spend his or her time and money, and these choices are essential to define consumer identity. Lifestyle defines a pattern of consumption that reflects a person’s choices of how to spend his or her time and money. These choices play a key role in defining consumer identity. 7.2.5 Psychographics Psychographics go beyond simple demographics to help marketers understand and reach different consumer segments. Psychographics involves the “use of psychological, sociological, and anthropological factors . . . to determine how the market is segmented by the propensity of groups within the market—and their reasons—to make a particular decision about a product, person, ideology, or otherwise hold an attitude or use a medium.” 7.2.5.1 AIO Dimensions Most contemporary psychographic research attempts to group consumers according to some combination of three categories of variables: activities, interests, and opinions, which we call AIOs for short. Figure 6 AIO Dimensions To group consumers into AIO categories, researchers give respondents a long list of statements and ask them to indicate how much they agree with each one. Thus, we can “boil down” a person’s lifestyle by discovering how he or she spends time, what he or she finds interesting and important, and how he or she views himself or herself and the world around him or her. 7.3 Now you know that a consumer’s personality influences the way they respond to marketing stimuli that brands have personalities that a lifestyle defines a pattern of consumption that reflects a person’s choices of how to spend their time and money, and these choices are essential to define consumer identity that psychographics go beyond simple demographics to help marketers understand and reach different consumer segments 7.4 Science Insight 7.4.1 Abstract Five studies using a variety of experimental approaches and secondary data sets show that a visual property present in all brand logos—the degree of (a)symmetry—can interact with brand personality to affect brand equity. Specifically, compared with symmetrical logos, asymmetrical logos tend to be more arousing, leading to increased perceptions of excitement. As such, consumers tend to perceive asymmetrical logos as more congruent with brands that have an exciting personality. This can boost consumers’ evaluations and the market’s financial valuations of such brands, a phenomenon referred to as the “visual asymmetry effect.” The studies also show that this interplay between brand personality and logo design occurs only for the personality of excitement and the visual property of asymmetry. These findings add to theories of visual design and branding and offer actionable insights to marketing practitioners. 7.4.2 Implications For theory • • Examines the joint effect of logo asymmetry and brand personality Highlights the importance of considering congruence among brand elements that are more sensory (e.g., logos) versus more cognitive (e.g., brand personality) in nature For Practice • • Design properties that are generally considered favorable for brands (e.g., visual symmetry) may backfire when they are not congruent with brand personality Implications likely extend to other visual brand elements, such as packaging, advertisements, and webpage and app interface designs 7.4.3 Now, You Know… • • that logo design affects perceptions of brand personality that visual design elements need to be carefully selected based on a brand’s existing brand personality 8 Persuasion 8.1 Attitudes 8.1.1 Components An attitude is an enduring organization of motivational, emotional, perceptual, and cognitive processes with respect to some aspect of our environment. It is a learned predisposition to respond in a consistently favorable or unfavorable manner with respect to a given object. Thus, an attitude is the way one thinks, feels, and acts toward some aspect of his or her environment, such as a retail store, television program, or product. Figure 7 Attitude Components and Manifestations • • • The cognitive component consists of a consumer’s beliefs about an object. For most attitude objects, people have a number of beliefs. Feelings or emotional reactions to an object represent the affective component of an attitude. A consumer who states “I like Diet Coke’’ or “Diet Coke is a terrible soda” is expressing the results of an emotional or affective evaluation of the product. The behavioral component of an attitude is one’s tendency to respond in a certain manner toward an object or activity. A series of decisions to purchase or not purchase Diet Coke or to recommend it or other brands to friends would reflect the behavioral component. 8.1.2 Multi-attribute model The most influential multiattribute model is called the Fishbein Model, named after its primary developer.28 The model measures three components of attitude: • • • Salient beliefs people have about an Ao (i.e., those beliefs about the object a person considers during evaluation). Object-attribute linkages, or the probability that a particular object has an important attribute. Evaluation of each of the important attributes. When we combine these three elements, we compute a consumer’s overall attitude toward an object (we’ll see later how researchers modify this equation to increase its accuracy). • • • • • • i = attribute j = brand k = consumer I = the importance weight given attribute i by consumer k b = consumer k’s belief regarding the extent to which brand j possesses attribute i A = a particular consumer’s (k’s) attitude score for brand j Basic multiattribute models contain three specific elements: • • • • Attributes Beliefs Object-attribute linkages Evaluation 8.2 Attitude Formation • • • Consistency Principle: According to the principle of cognitive consistency, we value harmony among our thoughts, feelings, and behaviors, and a need to maintain uniformity among these elements motivates us. This desire means that, if necessary, we change our thoughts, feelings, or behaviors to make them consistent with other experiences. Self-Perception Theory: Do we always change our attitudes to be in line with our behavior because we’re motivated to reduce cognitive dissonance? Self-perception theory provides an alternative explanation of dissonance effects. It assumes that we observe our own behavior to determine just what our attitudes are, much as we assume that we know what another person’s attitude is when we watch what he does. The theory states that we maintain consistency as we infer that we must have a positive attitude toward an object if we have bought or consumed it (assuming that we freely made this choice). Balance Theory: Balance theory considers how people perceive relations among different attitude objects, and how they alter their attitudes so that these remain consistent (or “balanced”). One study even found that when a person observes two other individuals who are eating similar food, they assume they must be friends! 8.3 Persuasion Persuasion is the active attempt to change attitudes in today’s dynamic world of interactivity, where consumers have many more choices available to them and greater control over which messages, they choose to process e.g., through social media. Video-on-demand services are a good example of being able to control out media environment. 8.4 The Source 8.4.1 Source credibility Source credibility refers to a communicator’s expertise, objectivity, or trustworthiness. This dimension relates to consumers’ beliefs that this person is competent and that he or she will provide the necessary information we need when we evaluate competing products. • • • • • • • • • Disclaimers: you often hear at the end of a commercial message that supply additional information the advertiser is required to provide (“possible side effects may include nausea, diarrhea, or death”). Although people tend to assume that people who speak faster are more intelligent, they may trust them less. Fake News: hoaxes spread by hackers or other outsiders—has caused many people to question the trustworthiness of even the most respected traditional and social media outlets. Although the term has been around for more than a century, it has only recently come into the spotlight especially due to Russia’s attempts to influence the 2016 U.S. presidential election. Sleeper Effect: in general more positive sources tend to increase attitude change, there are exceptions to this rule. In some instances, the differences in attitude change between positive sources and less-positive sources become erased over time. After a while, people appear to “forget” about the negative source and change their attitudes anyway. We call this process the sleeper effect. Native Advertising: This term refers to digital messages designed to blend into the editorial content of the publications in which they appear. The idea is to capture the attention of people who might resist ad messages that pop up in the middle of an article or program. These messages may look a lot like a regular article, but they often link to a sponsor’s content. Knowledge Bias: implies that a source’s knowledge about a topic is not accurate. Reporting Bias: occurs when a source has the required knowledge but we question his or her willingness to convey it accurately—as when a racket manufacturer pays a star tennis player to use its products exclusively. The source’s credentials might be appropriate, but the fact that consumers see the expert as a “hired gun” compromises believability. Source Attractiveness: refers to the social value recipients attribute to a communicator. This value relates to the person’s physical appearance, personality, social status, or similarity to the receiver (we like to listen to people who are like us). Star Power: Star power works because celebrities embody cultural meanings—they symbolize important categories like status and social class. These messages are more effective when there’s a logical connection between the star and the product. Spokescharacters: some marketers seek alternative sources to celebrities, including cartoon characters and mascots. As the marketing director for a company that manufactures costumed characters for sports teams and businesses points out, “You don’t have to worry about your mascot checking into rehab.”72 Researchers report that spokes characters, such as the Pillsbury Doughboy, Chester Cheetah, and the GEICO Gecko, do, in fact, boost viewers’ recall of claims that ads make and also yield higher brand attitudes 8.5 The Message Pictures vs. Words • • • Repetition: Advertisers find positive effects for repetition even in mature product categories: Repeating product information boosts consumers’ awareness of the brand, even though the marketer says nothing new. Too much repetition creates habituation, whereby the consumer no longer pays attention to the stimulus because of fatigue or boredom. o people tend to like things that are more familiar to them, even if they were not that keen on them initially. Psychologists call this the mere exposure phenomenon. Structure of the Argument: Many marketing messages are like debates or trials: A source presents an argument and tries to convince the receiver to shift his or her opinion. As you’ve no doubt guessed, the way we present the argument may be as important as what we say. Comparative Ads: refers to a message that compares two or more recognizable brands and weighs them in terms of one or more specific attributes. Sometimes these attempts at persuasion attack the brand’s own messages rather than specifics of the product. 8.5.1 Message Appeals • • • • Emotional vs. Rational: which is better: to appeal to the head or to the heart? The answer often depends on the nature of the product and the type of relationship consumers have with it. It’s hard to gauge the precise effects of rational versus emotional appeals. Sex Appeals: a recent study’s findings sum up the impact of sex appeals: Yes, they get noticed and remembered but many viewers don’t recall what the ad was plugging. And, males do like provocative messages more than females, but this doesn’t translate into stronger brand attitudes Humor Appeals: Do humor appeals work? Overall, funny advertisements do get attention. One study found that recognition scores for humorous liquor ads were better than average. However, the verdict is mixed as to whether humor affects recall or product attitudes in a significant way. o A funny ad inhibits counterarguing (in which a consumer thinks of reasons why he or she doesn’t agree with the message); this increases the likelihood of message acceptance because the consumer doesn’t come up with arguments against the product. Fear Appeals: Fear appeals emphasize the negative consequences that can occur unless the consumer changes a behavior or an attitude. These types of messages are fairly common in advertising, although they are more common in social marketing contexts in which organizations encourage people to convert to healthier lifestyles by quitting smoking, using contraception, or relying on a designated driver. 8.6 Elaboration Likelihood Model Figure 8 THE ELABORATION LIKELIHOOD MODEL (ELM) OF PERSUASION 8.7 Now you know • hat attitudes have a cognitive, affective, and behavioral component • • we form attitudes in several ways how marketers try to change our attitudes 8.8 Science Insight Kim, T. W., & Duhachek, A. (2020). Artificial Intelligence and persuasion: A construal-level account. Psychological Science, 31(4), 363-380. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F0956797620904985 8.8.1 Abstract Although more individuals are relying on information provided by nonhuman agents, such as artificial intelligence and robots, little research has examined how persuasion attempts made by nonhuman agents might differ from persuasion attempts made by human agents. Drawing on construal-level theory, we posited that individuals would perceive artificial agents at a low level of construal because of the agents’ lack of autonomous goals and intentions, which directs individuals’ focus toward how these agents implement actions to serve humans rather than why they do so. Across multiple studies (total N = 1,668), we showed that these construal-based differences affect compliance with persuasive messages made by artificial agents. These messages are more appropriate and effective when the message represents low-level as opposed to high-level construal features. These effects were moderated by the extent to which an artificial agent could independently learn from its environment, given that learning defies people’s lay theories about artificial agents. Construal: In social psychology, a construal is a way that people perceive, comprehend, and interpret their world, particularly the acts of others toward them. • • High construal action: emphasizes why an action is performed Low construal action: emphasizes how an action is performed 8.8.2 Conclusion • • AAs are perceived as low-construal agents because of the fact that people hold a lay theory that AAs do not have superordinate goals and cannot learn from their experiences or possess consciousness like humans do. Individuals perceive greater appropriateness and are more persuaded when an AA’s persuasive messages highlight low-construal as opposed to high-construal features. à People rely on AAs more in contexts that induce low construal: events or objects that are temporally, socially, and spatially proximate and occurring with high probability (e.g., short-term investments) 8.8.3 Now, You Know… • • that digital agents are perceived to have no autonomous goals that this perception affects how persuasive messages by digital agents are 9 Consuming 9.1 The Consumption Situation A consumption situation includes a buyer, a seller, and a product or service—but also many other factors, such as the reason we want to make a purchase and how the physical environment makes us feel. Figure 9 ISSUES RELATED TO PURCHASE AND POSTPURCHASE ACTIVITIES 9.2 Situational Factors and Usage Situation gives one example of how a marketer fine-tunes its segmentation strategy to the usage situation. When we list the major contexts in which people use a product (e.g., snow skiing and sunbathing for a sun screen lotion) and the different types of people who use the product, we can construct a matrix that identifies specific product features we should emphasize for each situation. 9.3 Time poverty Many consumers believe they are more pressed for time than ever before; marketers label this feeling time poverty. The problem appears to be more perception than fact. The reality is that we simply have more options for spending our time, so we feel pressured by the weight of all of these choices. In 1965, the average U.S. woman spent about 32 hours per week on housework; the time today is about half of that. 9.3.1 Consequences Time poverty increases… Frequency of buying pre-prepared and take-away foods Use of medication to cope with demands and avoid visits to doctors Depression Emotional exhaustion Negative mood Work-vs-family conflict Trouble concentrating at work Physical inactivity Time poverty decreases… Job satisfaction Self-assessed mental health Frequency of physical activity Life satisfaction 9.4 Retail Environment 9.5 Postpurchase behavior As the figure indicates, some purchases are followed by a phenomenon called postpurchase dissonance. This occurs when a consumer doubts the wisdom of a purchase he or she has made. Other purchases are followed by nonuse. The consumer keeps or returns the product without using it. Most purchases are followed by product use, even if postpurchase dissonance is present. Figure 10 Postpurchase Consumer Behavior 9.5.1 Postpurchase Dissonance Postpurchase Dissonance occurs when a consumer has doubts or anxiety regarding the wisdom of a purchase made and is a function of the following: • • • The degree of commitment or irrevocability of the decision. The easier it is to alter the decision, the less likely the consumer is to experience dissonance. The importance of the decision to the consumer. The more important the decision, the more likely dissonance will result. The difficulty of choosing among the alternatives. The more difficult it is to select from among the alternatives, the more likely the experience and magnitude of dissonance. Decision difficulty is a function of the number of alternatives considered, the number of relevant attributes associated with each alternative, and the extent to which each alternative offers attributes not available with the other alternatives. • The individual’s tendency to experience anxiety. Some individuals have a higher tendency to experience anxiety than do others. The higher the tendency to experience anxiety, the more likely the individual will experience post purchase dissonance. 9.5.2 Postpurchase Dissonance Reduction After the purchase is made, the consumer may use one or more of the following approaches to reduce dissonance: • • • • Increase the desirability of the brand purchased Decrease the desirability of rejected alternatives Decrease the importance of the purchase decision Reverse the purchase decision (return before use) 9.5.3 Product Disposition illustrates the various alternatives for disposing of a product or package. Unfortunately, while “throw it away” is only one of many disposition alternatives, it is by far the most widely used by consumers. Figure 11 Disposition Alternatives 9.6 Now you know • • • • that many factors influence what we buy how marketers and designers try to ‘trick’ us making unplanned purchases how consumers can resolve postpurchase dissonance that recycling might not be the best way to go to solve the waste problem 9.7 Science Insight Mookerjee, S., Cornil, Y., & Hoegg, J. (2021). From waste to taste: How “ugly” labels can increase purchase of unattractive produce. Journal of Marketing, 85(3), 62-77. 9.7.1 Abstract Food producers and retailers throw away large amounts of perfectly edible produce that fails to meet appearance standards, contributing to the environmental issue of food waste. The authors examine why consumers discard aesthetically unattractive produce, and they test a low-cost, easy-to-implement solution: emphasizing the produce’s aesthetic flaw through “ugly” labeling (e.g., labeling cucumbers with cosmetic defects “Ugly Cucumbers” on store displays or advertising). Seven experiments, including two conducted in the field, demonstrate that “ugly” labeling corrects for consumers’ biased expectations regarding key attributes of unattractive produce—particularly tastiness—and thus increases purchase likelihood. “Ugly” labeling is most effective when associated with moderate (rather than steep) price discounts. Against managers’ intuition, it is also more effective than alternative labeling that does not exclusively point out the aesthetic flaw, such as “imperfect” labeling. This research provides clear managerial recommendations on the labeling and the pricing of unattractive produce while addressing the issue of food waste. 9.7.2 Conclusion • • • Clear guidance to managers on whether and how to label unattractive produce, and which price discount will maximize sales. “Ugly” labeling may also further increase the effective- ness of more labor-intensive and costly interventions that rely on educating consumers about the environmental consequences of food waste. “Ugly” labeling may also overcome retailers’ reluctance to sell unattractive produce, whether it is because they fear a lack of consumer in or they are concerned that steep price discounts would hurt their bottom line. 10 Social Class 10.1 Economic Inequality 10.1.1 The Global Pyramid of Wealth The Highest-Earning 20% of U.S. Households Make More Than Half of all U.S. Income. Gini Coefficient Among G7 Countries. To compare income inequality across countries, the OECD uses the Gini coefficient, a commonly used measure ranging from 0, or perfect equality, to 1, or complete inequality. 10.2 Social Stratification • • Social Stratification: Processes in a social system by which scarce and valuable resources are distributed unequally to status positions that become more or less permanently ranked in terms of the share of valuable resources each receives (a creation of artificial divisions). o The process of social stratification refers to this creation of artificial divisions, “those processes in a social system by which scarce and valuable resources are distributed unequally to status positions that become more or less permanently ranked in terms of the share of valuable resources each receives. Societal Rank: One’s position relative to others on one or more dimensions valued by society, also referred to as social class and social standing. Figure 12 Social Standing Is Derived and Influences Behavior 10.3 Status Symbols Invidious distinction / consumption: we buy things to create invidious distinction; this means that we use them to inspire envy in others through our display of wealth or power. Conspicuous consumption: to refer to people’s desires to provide prominent visible evidence of their ability to afford luxury goods. o that is, they purchase and use automobiles, homes, yachts, clothes, and so forth primarily to demonstrate their great wealth. Leisure class: phenomenon of conspicuous consumption was, for Veblen, most evident among what he termed the leisure class; people for whom productive work is taboo. In Marxist terms, such an attitude reflects a desire to link oneself to ownership or control of the means of production, rather than to the production itself. Those who control these resources, therefore, avoid any evidence that they actually have to work for a living, as the term idle rich suggests. Trophy wives: wives are an economic resource. He criticized the “decorative” role of women, as rich men showered them with expensive clothes, pretentious homes, and a life of leisure as a way to advertise their own wealth (note that today he might have argued the same for a smaller number of husbands). Cougars: In recent years the tables have turned as older women—who increasingly boast the same incomes and social capital as their male peers—seek out younger men as arm candy. These so-called cougars (a term popularized by the TV show Cougar Town) are everywhere; surveys estimate that about one-third of women older than age 40 date younger men. Brand prominence: brand prominence as the extent to which a product has visible markings that help ensure observers recognize the brand. Manufacturers can produce a product with “loud” or conspicuous branding or tone it down to “quiet” or discreet branding to appeal to different types of consumers Status signaling: 10.4 Status Signaling One set of researchers labels these differences brand prominence. They assign consumers to one of four consumption groups (patricians, parvenus, poseurs, and proletarians) based on their wealth and need for status. When they looked at data on luxury goods, the authors found different classes gravitated toward different types of brand prominence. Brands like Louis Vuitton, Gucci, and Mercedes vary in terms of how blatant their status appeals (e.g., prominent logos) are in advertisements and on the products themselves— or in other words, in the type of status signaling they employ. Figure 13 A TYPOLOGY OF STATUS SIGNALING 10.5 Upward Pull describes the upward-pull strategy often associated with the class to mass approach (Companies, in a strategy termed class to mass, have responded by expanding opportunities for less affluent consumers to afford luxury). Figure 14 Figure 14 Upward-Pull Strategy Targeted at Middle Class 10.6 Now you know that income is distributed extremely unequally across the globe and why we seem to be ok with that that we group consumers into social classes that say a lot about where they stand in society individuals like to make a statement about where their societal standing, or the class they aspire to belong to o Conspicuous consumption 10.7 Science Insight Hagerty, S. F., & Barasz, K. (2020). Inequality in socially permissible consumption. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 117(25), 14084-14093. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2005475117 10.7.1 Abstract Lower-income individuals are frequently criticized for their consumption decisions; this research examines why. Eleven preregistered studies document systematic differences in permissible consumption—interpersonal judgments about what is acceptable (or not) for others to consume—such that lower-income individuals’ decisions are subject to more negative and restrictive evaluations. Indeed, the same consumption decisions may be deemed less permissible for a lower-income individual than for an individual with higher or unknown income (studies 1A and 1B), even when purchased with windfall funds. This gap persists among participants from a large, nationally representative sample (study 2) and when testing a broad array of “everyday” consumption items (study 3). Additional studies investigate why: The same items are often perceived as less necessary for lower- (versus higher-) income individuals (studies 4 and 5). Combining both permissibility and perceived necessity, additional studies (studies 6 and 7) demonstrate a causal link between the two constructs: A purchase decision will be deemed permissible (or not) to the extent that it is perceived as necessary (or not). However, because—for lower-income individuals—fewer items are perceived as necessary, fewer are therefore socially permissible to consume. This finding not only exposes a fraught double standard, but also portends consequential behavioral implications: People prefer to allocate strictly “necessary” items to lower-income recipients (study 8), even if such items are objectively and subjectively less valuable (studies 9A and 9B), which may result in an imbalanced and inefficient provision of resources to the poor. 10.7.2 Conclusion • • Lower-income people are socially permitted to consume less because they are presumed to need less Not only do lower-income individuals face harsher interpersonal judgment for deviating from “necessary” purchases, but there are fewer items that fit within the permissible categorization of “necessary” in the first place. à People appear more comfortable directing (and limiting) the decisions of the poor.