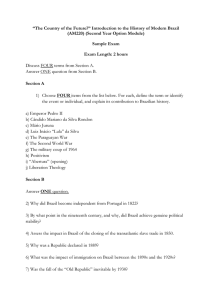

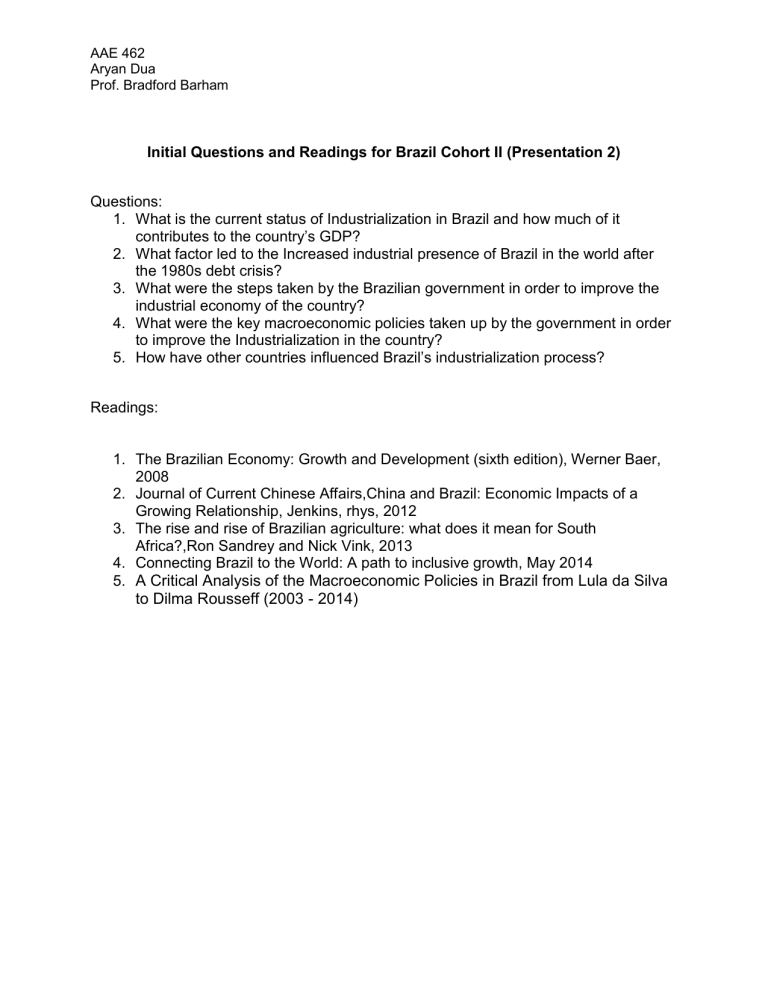

AAE 462 Aryan Dua Prof. Bradford Barham Initial Questions and Readings for Brazil Cohort II (Presentation 2) Questions: 1. What is the current status of Industrialization in Brazil and how much of it contributes to the country’s GDP? 2. What factor led to the Increased industrial presence of Brazil in the world after the 1980s debt crisis? 3. What were the steps taken by the Brazilian government in order to improve the industrial economy of the country? 4. What were the key macroeconomic policies taken up by the government in order to improve the Industrialization in the country? 5. How have other countries influenced Brazil’s industrialization process? Readings: 1. The Brazilian Economy: Growth and Development (sixth edition), Werner Baer, 2008 2. Journal of Current Chinese Affairs,China and Brazil: Economic Impacts of a Growing Relationship, Jenkins, rhys, 2012 3. The rise and rise of Brazilian agriculture: what does it mean for South Africa?,Ron Sandrey and Nick Vink, 2013 4. Connecting Brazil to the World: A path to inclusive growth, May 2014 5. A Critical Analysis of the Macroeconomic Policies in Brazil from Lula da Silva to Dilma Rousseff (2003 - 2014) AAE 462 Aryan Dua Prof. Bradford Barham Initial Draft Individual Presentation Notes Notes – - - - - - - - - - Between 1982 and 1994, Brazil experienced crippling hyperinflation that was typical of Latin America during the last decades of the twentieth century. Between 1990 and 1995, for example, inflation averaged 764% a year. The debate on the role of government in economic growth has not lost its momentum, even though recent experiences have caused it to refocus from yes/no questions about government involvement in the market to questions concerning the efficiency and long-term consequences of state intervention. Moreover, measures inspired by the Washington Consensus – which covered all kinds of economic activities and included macroeconomic adjustment, rearrangement of the financial sector, privatization of state-owned enterprises (SOEs), liberalization of trade, and welfare and labor reforms – have changed the Brazilian economy immensely and fostered a new approach to development. Neoliberal reforms were carried out in tandem with a political transformation from authoritarianism to democracy, a transition common to many Latin American countries. This may serve as a partial explanation for the failure of the initial stages of liberalization in the region because a fledgling democracy not deeply rooted in the institutional system usually offers more opportunities for special-interest groups to pursue their goals. Nevertheless, structural reforms created a new base for a modern Brazilian economy and strongly tied the country to the global marketplace. An important question that should be addressed here is what role the industrial policies implemented by the government in the 21st century has played in the structural adjustment and the economic turmoil of Brazil from the 1990s. In order to deal with this turmoil, Brazil used a mix of Monetarism and Structuralist strategies that include tight monetary policy at times and efforts to break inertial inflation by measures that include introducing new currency, austerity, and privatepublic compacts to stop indexing. In the 1990s, the efforts by President Collar had a devasting impact on the country where he tried to curb the inflation by freezing all the liquid assets of the country overnight and once and for all to beat the inflation levels in the country by borrowing over a sum of $45.7 billion and not repaying until the next 18 months. The "Collor plan" left citizens penniless, threw the economy into chaos, drove companies crazy and helped cause one of the worst recessions ever in this vast country with the Southern Hemisphere's largest economy. After the orthodox macroeconomic plan implementations in the early 1990s, Collor was overthrown and Fernando Henrique Cardoso, Finance Minister in Brazil between May 1993 and April 1994 and President from 1995 to 2003, introduced the “Plano AAE 462 Aryan Dua Prof. Bradford Barham - - Real” that saved Brazil from the inflation that had plagued the nation. The main components of the plan included introducing a new currency, the Real, and keeping the currency exchange-rate pegged until 1999, when it was deemed stable enough to float. By 2006, for the first time in over 50 years, Brazil’s GDP growth was greater than its average inflation. The most notable achievement in the 1990s was the attainment of price stability shortly after the introduction of the Real Plan. As indicated in Table 2, the general price increase, after having peaked at 2,406 per cent in 1994, dramatically declined in the subsequent years, not exceeding one digit from 1997 onwards. This accomplishment mainly resulted from the imposition of a very tight monetary policy, combined with the delayed effects of opening the economy to international competition. One of the most striking disappointments of the 1990s was the anaemic growth performance of the economy. The average yearly growth rate in the 1990s was 1.82 per cent which was lower than the average growth rate in the so-called ‘lost decade’ of the 1980s which stood at 3.03 per cent. Table 4a indicates that the weakest performance was displayed by the industrial sector. In part, the poor output performance of industry is reflective of increasing import penetration which forced domestic enterprises to cede market share to foreign producers. The poor industrial output performance had serious distributional consequences as firms shed labor. (refer to graph below) AAE 462 Aryan Dua Prof. Bradford Barham - - - - - Following the Cardoso Presidency, President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, who was in office between 2003 and 2010, enacted a series of policies that continued to bolster the Brazilian economy by supporting a growth of the middle class. Lula reduced poverty in Brazil by 24% between 2003 and 2010 through a series of distributional programs, subsidized housing loans, and significant increases in the minimum wage that allowed 13 million Brazilians to escape poverty and an additional 12 million to escape severe economic deprivation. On August 2, 2011, Brazilian President Dilma Rousseff announced the so-called Greater Brazil Plan (Plano Brasil Maior), an industrial policy aimed at improving local industry competitiveness to sustain growth and job creation in a time of economic uncertainty. The Greater Brazil Plan is the third industrial policy announced by the Brazilian federal government in the past decade, following the 2004 Industrial, Technological, and Foreign Trade Policy (PITCE) and the 2008 Productive Development Policy (PDP). The first incentive of this plan was to generate investments and innovation which have been implemented by tax relief, financing for investment and innovation and a new legal framework of innovation. The second action is centered on improving the foreign trade and includes a battery of tax relief on exports, trade remedies, financing and guarantee for exports, and trade promotion. Finally, the last action aims at industry and domestic market defense and compromises a new special automotive regime, tax exemptions on payrolls, government procurement and harmonization of funding policies Despite the application of these programs, the performance of the industrial sector, especially manufacturing, fell short of expectations during the application of the plan. One of the reasons was the poor performance of GDP growth and the appreciation of the real, which negatively impacted in the manufacturing competitiveness. As a result, the manufacturing’s share to GDP had followed its long run tendency to decline in contrast to services’ increasing share. From 2005 to 2012, Brazil’s commodities exports increased from $11 billion to $64 billion—but over the same period, a trade surplus of $20 billion in AAE 462 Aryan Dua Prof. Bradford Barham manufactured goods turned into a trade deficit of $45 billion (Exhibit E5). As the commodities boom caused the real to appreciate sharply, Brazilian goods have become less cost competitive in global markets. Brazil’s exports are equivalent to 13 percent of GDP, far below India (24 percent) or Mexico (33 percent). - Despite Brazil’s success and growth, it finds itself at a critical crossroads. The country has never successfully sustained a democracy, low rates of inflation, and significant economic growth simultaneously for any significant period. Furthermore, bad growth productivity due to a weak infrastructure and notoriously high interest rates continue to plague the country. Violent crime, irresponsible government spending and corruption, and an education system in need of reform are reminders of how far Brazil must go before it can truly declare itself a stable, first world nation with a strong economy.