Japanese City vs. Countryside: Culture & Questionnaires

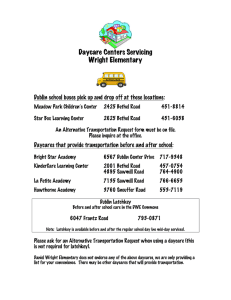

advertisement

UNIVERSITI TEKNOLOGI MARA ASASI TESL PROGRAMME TSL025 – ACADEMIC WRITING APPENDICES TITLE: The Japanese: in the City vs in the Countryside Name : NAYLI BATRISYIA AN-NASIHA BINTI NOR’AZLAN (2020463758) Group : T03 Lecturer : FATIMAH AZZAHRA BT MD RAUS Submission Date : 5th MARCH 2021 Theme: : CULTURE QUESTIONNAIRES AND RESPONSES SIMILARITIES DIFFERENCES The people in the city has less interest in their neighbours than in the countryside. There must be differences depending on where, but I believe the countryside is more conservative in general, which means tighter (or narrower) group thinking than the city. Overall well-manneredness and orderliness in behavior (These are general tendencies of the Japanese as a whole. Can be both merits and demerits.) Average level of basic education (Almost all of the people in Japan read and write thousands of Chinese characters smoothly, even from poor backgrounds. Most Japanese citizens raised in whatever area can calculate basic arithmetic quickly by heart, even when dealing with multi tasks like choosing what to buy at shops.) Quality hospitality of all kinds of shops and stores (The beautiful Japanese “omotenashi” spirit is prevalent anywhere. You can receive meticulous, pleasantly courteous services even at a convenience store in a deserted village.) Scarcity of fluent, communicable English speakers (Of course, in cities you can meet a somewhat larger number of people who can make understood themselves to you in English, but overall, anywhere in Japan, we can see only few speaking the world’s universal language eloquently.) Level and quality of supplementary and higher education (we can receive far more resourceful and effective education in the cities). Average amount of salary (Those in the countryside on average earn less than a half of their city counterparts.) Number of prevalence of well-paid jobs. (Local government staffs and public school teachers are the two most lucrative jobs available in the countryside.) Proportion of youngsters and elderlies. (Japan as a whole is aging, but the young-old ratio is unbelievably slanted to the latter in the countryside. Youngsters are almost imaginary beings there.) Housing environments (This might be the sole strength of the countryside. We can get accommodated in a spacious apartment or house for far lower rents.) Styles of reporting to work (The majority of country dwellers report to work by car while city folks mostly use trains.) Density of human relationship (This May apply to most remote communities all around the world, but Japan is unique in that all the neighbors are of the same one race and subconsciously expect others to behave on the unwritten social norms. So suffocating.) Level of safety (You May think of this as an advantage of living in the depopulated countryside. Cities like Tokyo are full of evil-minded con artists, malicious criminals, and pugnacious hoodlums.) Their hardworking traits, willing to give everything to produce the best result. People in the city tend to be less friendly than the one in the countryside They share the same social codes. They Not many differences actually. Most of the usually also appreciate the same range of food. Japanese living in the countryside are either elders, or factory employees. Lots of Japanese in both, a limited number of foreigners in the cities, very few in the countryside. Elementary, Middle and High Schools are run by the central government and are good in both places. Economic opportunity is in the cities, the towns and villages in the countryside are aging, decaying and dying. Average age of residents is much older in rural areas. One similar is contry side and city are good people and respect people. Contry and city is cheerful people. Contry is usual live a healthy life and have many good advice and culture life from old people, but city is many fast food. Contry also have more frend people but city not so frend because not know each other. My name is Naoko Tamura. I'm 18 years old living in Japan. The similarity is that we can receive information from the internet or TV. Anyone can get anything with a delivery service, even if there is no store nearby(amazon etc). The difference is 1, There are many elderly people in the countryside and many young people in the city,because there are more universities in the city and more job vacancies. Once in the city, young people rarely do not come back to their hometown. 2, There is an educational gap. As a result, Japan which is an educational background socity, there are more rich people in the city.There are more cram schools in the city. We need money to go to high school and college.Especially, universities cost a lot, so rich families have an advantage. 3, Countryside people are deeply connected.On the other hand, there are many nuclear families in the city. Due to this, the discovery was delayed, and many elderly people died lonely. Young people do not live with their grandparents, so they have to leave their children in a nursery.The lack of nursery schools is one of the social problems. I hope it helps you. They are both polite and respectful The countryside people are calm and peaceful and the city people are busy and occupied They both are friendly and polite One's in the countryside are less money minded and more religious The same between them is that they both live respectful and work with eachother The country is much calmer, not as busy, collectivist and relaxing lives compared to the city where it is much busier, people are on the go, they have a busy scheduled daily lives strong sense of self countryside more considerate, less money orientated and nicer Not a lot of similarities. Maybe a little bit of pride for the country. Citizens that reside in cities tend to be more progressive, while citizens that live in the countryside tend to be more traditional. Everybody works really hard Japanese who lives in the city are more social than people who live on the countryside 3 MAIN IDEAS (1 SIMILARITY AND 2 DIFFERENCES) SIMILARITY: Japanese common traits DIFFERENCES: 1. Economic and academic inequalities 2. Youth and elders quota ANNOTATED ARTICLES Japan’s rural schools run out of students https://www.theguardian.com/world/2015/may/11/japan-rural-schools-dwindling-students Urban migration, dwindling birthrates and an ageing society are combining to present Japanese education authorities with a big problem. In Aone’s historic wooden schoolhouse, decked out in the kind of bright artwork done by kids the world over, there are two classrooms, each containing three desks that sit marooned in the middle of a space made for many more. At breaktime, a boy kicks a football around the yard by himself. “It’s a little bit lonely,” said Taiki Kato, 11, who said he was looking forward to going to middle school next year. “It’s a bit bigger and there might be kids from other elementary schools.” The middle school has eight students. The elementary school, where Kato started sixth grade last month, has six. And two of them, the only girls, are from the same family. That meant Yukari Sudo could easily master everyone’s names in her first week as principal of the elementary school in this small village, nestled in mountains 80km but a world away from the tightly packed metropolis of Tokyo. “When I was greeting 900 kids in the morning, I could recognise them, but I might not be able to remember their names,” said Sudo, who recently moved to Aone after being vice-principal at a much bigger school. Now almost a third of Japan’s 127 million people live in the greater Tokyo area Learning the staff members’ names would take longer — after all, there were twice as many of them. Aone, population 638, has two small general stores and a grimy restaurant that could make a claim for serving the worst food in Japan. The average age here is 62. One of the most common modes of transport is a walker with wheels that doubles as a shopping cart and mobile seat. This scene is played out across Japan, from the sparsely populated island of Hokkaido in the north to the alps along the west coast to here, commuting distance from the capital. For decades, Japanese people have been deserting these regions in droves, heading to the bright lights and job opportunities of Tokyo. Now, almost a third of Japan’s 127 million people live in the greater Tokyo area. With a rapidly ageing society and miserable birthrate, Japan has not been able to replace the people leaving outlying towns and cities as quickly as they’ve departed. And the situation is only going to get worse. The number of children younger than 14 is expected to almost halve by 2050, according to government projections, as fewer people have fewer children and the proportion of the population at child-bearing age shrinks. (There are expected to be 5 million Japanese in their 90s by the middle of the century). Like this one, nearly half the public elementary and junior high schools in Japan are smaller than the education ministry’s guidelines. The government in Tokyo would like to close these small schools and fold them into others nearby. Used in the third paragraph. “The government in Tokyo would like to close these small schools and fold them into others nearby,” tells us how the government has started the inequality treatment in terms of education to their citizens who live in the countryside. Due to the speedily aging society and lack of birthrate, Japan has not been able to catch up to the number of people leaving the countryside to live in the city. Then, the youngsters there, despite them being in a small amount, having a hard time getting to the nearest school. This may seem the best solution but the government could have advanced the facilities in the countryside and add more job opportunities so that people will not have to leave their homes. “If a small school has less than five classes, it should seriously and aggressively consider integrating with another school with a sense of urgency,” said Hiroto Iwaoka, chief of compulsory education reform at the ministry. This is not just about economics. It’s also driven by concern that kids at small schools don’t develop the social skills they’ll need in the wider world with the same handful of classmates every day, year in and year out. In Hokkaido, some children are already commuting 50km by bus every day because of school closures, while one tiny school in Nagano, in the alps, can’t close because the nearest alternative is a 90-minute drive away. But the central government faces a significant level of local resistance, and although it holds almost all the purse strings, it must defer to district authorities. Kyoko Inoue, chief of educational affairs in Sagamihara, the municipality that incorporates Aone, says there’s no plan to close the elementary school here, even though there’s a much bigger school, with about 80 kids, 8km away, albeit down a windy narrow mountain road. “A school often functions as a core of a community,” she said. “We want a school to be something a local community desires.” Aone’s elementary school certainly has strong links to the community. It has been here for 142 years. At its peak, in 1945, 254 students sat in its classrooms. In the 1960s, it still had close to 200. Then a gradual but steady decline set in. Even now, the whole building – with its music room complete with grand piano, science room stocked with lab equipment and well-appointed library – is operational, although the rooms are heated only when they are used. For “integrated life studies” one day recently, the six kids walked up the road to a field where they planted potato seeds to a soundtrack of birdsong, then traipsed back along a forest path. Next they had lunch – grilled fish, rice, and soup with tofu, bamboo shoots and mountain asparagus – while classical music played in the background. Afterwards the six of them collected shiitake mushrooms from the forest, then did an impressive array of stretching exercises in the frigid gym. The school does manage to have sports days, even though there aren’t enough players to form a whole football team and the teachers have to be careful not to put too many kids in the cheering squad at once or there will be no one to spur on. There are educational constraints, too. Kotoe Arakawa, who teaches the younger class, has to teach a lesson to three kids of different ages within a 45-minute time slot. And she can’t exactly tell them to discuss a subject with their peers while she teaches a different grade level. In a bigger school, children learn how to live in the real world, these kids sometimes find it hard to speak out Sachiko Kaneko, who teaches the three sixth-graders, said she worries that her students are not exposed to a variety of ideas. “When you have a bigger class, you can divide them into small groups and get them to come up with ideas, present them to the class,” Kaneko said. “But when they’re only one student in each grade, you can’t do that.” Indeed, throughout the day, the students were barely unsupervised for a minute, having a teacher over their shoulders correcting them while they were drawing cherry blossoms during art class and closely monitoring them as they spaced out their potato seeds. “In a bigger school, children learn social skills and how to live in the real world,” said Arakawa. “These kids are so well behaved and so gentle, so when they get into a bigger group they sometimes find it hard to speak out.” But there are upsides to having such a small school, the teachers say. “There are no students that get left behind here, because we stick to the subject until each kid gets it,” Arakawa said. The education ministry in Tokyo suggests two courses of action for these small schools. One is to integrate them with bigger ones, which the local district has ruled out for now. The second is to cooperate with nearby schools by holding joint lessons and by using technology. The Aone school has only three joint classes with its closest neighboring school each year — though it’s just 20 minutes away – and decided IT was too complicated, even in high-tech Japan. There are no computers in the classrooms. Masaaki Hayo, a professor at Bunkyo University, said this stems from an entrenched belief that education must entail direct communication, that using technology is a form of neglect. “If schools follow government-approved curriculums, some activities can only be done in a [bigger] group. IT can be a way to create a bigger group of children and have them be more active,” he said. And that would help keep endangered schools open. Chiharu Yamaguchi, the mother of the only two girls, moved to Aone nine years ago when she got married. She was shocked at how small the town was. “I was worried about sending my kids to the school, but we decided to try it and I got to know the school and the parents and the teachers,” she said, as she waited by the school gate to walk her daughters home. “And that got rid of my worries.” URBAN AND RURAL LIFE IN JAPAN Urban Life in Japan Many Japanese customs, values and personality traits arise from the fact that Japanese live so close together in such a crowded place. Everyday the Japanese are packed together like sardines on subways and in kitchen-size yakatori bars and sushi restaurants. A dozen lap swimmers may squeeze into single lane at a swimming pool. Bicycles and pedestrians fight for space on crowded sidewalks, which are especially packed on rainy days and sunny days, when umbrellas are out in force. If there weren't such strict rules and strong pressures to obey them people would be all over each other, in each other's face, and at each other's throats. In Japanese cities there are recorded messages everywhere telling you what to do: at crosswalks, on buses, on subways. Regular announcements warn subway riders to stand back from the edge of the platform. Sometimes they tell you things like "don't forget your umbrellas," "please refrain form using mobile phones" and "keep the city clean and tidy." There are flagmen for sidewalks near construction sites. Japan has managed to keep major department stores and shopping areas downtown rather than relying suburban shopping malls, which have kept downtown alive and prosperous. Urban activity is often concentrated around the train and subway stations. Japanese cities are very clean. Graffiti is hard to find and when it found it often has an upbeat message like “Find Your Dream." It is not uncommon to see a uniformed man down on his knees scrapping a wad of gum the pavement or a policeman issue a ticket to someone for smoking on the streets. Even so the number of rats in the cities appears to be on the rise. They have been blamed for starting fires by nibbling through electrical wires and making nests in vending machines. Many of the rats are roof rats which are harder to control than the more common Norway rat. The volume ratio for high-rise residential building promotion areas was raised, and in measuring the volume ratio for condominiums, steps and halls for common use were dropped from the items to be counted in the volume. This measure substantially increased the volume that could be used for living space itself. A 1998 revision to the Architectural Standards Law permitted designated private organizations to perform building inspections previously performed only by local government bodies. [Source: Web-Japan, Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Japan] In a survey in 2011 by human resources consultant ECA International, Tokyo was listed as the world's most expensive place to live with a typical two-bedroom apartment renting for $4,352 a month Used in the third paragraph. “Tokyo was listed as the world’s most expensive place” shows us that while living in a convenient city like Tokyo where you have got it all, it also comes with a high-priced living style you are going to have to bear. , ahead of Moscow at No. 2 where two-bedroom apartments rented for $3,500 a month. As for 2012, The Guardian reported: “Tokyo has regained the dubious honour of being the world's most expensive city, where a cup of coffee will set you back £5.25, a newspaper £4 and a litre of milk £2. The Japanese capital topped the annual cost-of-living survey by the HR consultants Mercer, which ranks cities according to the needs of expatriates. Luanda, in Angola, where more than half the population of 5 million live in poverty and where the Foreign Office advises visitors not to venture out at night, was the second most expensive. The cheapest city was Karachi, in Pakistan, where the cost of living was a third of that in Tokyo, closely followed by Islamabad. [Source: The Guardian, June 13, 2012] Japan’s Free Childcare Program No Panacea for Daycare Waitlists Politics Society Lifestyle Jun 11, 2019 Suzuki Wataru [Profile] Free preschool education and childcare starting in October 2019 could increase the number of children waiting for daycare places, already a serious problem, and make things difficult for families with young children. An economist who experienced the daycare hunt for his own three children offers a prescription for eliminating waitlists. A new government program offering free preschool education and childcare is slated for launch in October 2019. Beginning that month, for all families with children aged 3 to 5, and for low-income families with children up to age 2, the use of all preschool education or childcare facilities—not just ninka hoikuen, or licensed daycare centers, for which the central government covers operating costs—will be free. Government and daycare officials have been optimistic that free preschool will not substantially increase the number of children waiting for daycare places, since daycare fees for low-income families are very low to start with, and most 3- to 5-year-olds already attend daycare or kindergarten. Used in the fourth paragraph. “A new government program offering free preschool education and childcare…..free preschool will not substantially increase the number of children waiting for daycare places” tells us that the government has taken actions regarding the concern “lacking in nursery schools” but turns out it is still not enough as other new problems have arisen such as the subsidy given is not enough and fair to every childcare at every place. The solution may have only benefits to one side only. However, I don’t share their optimism. Even though the program has not started yet, municipalities are reporting that applications for licensed daycares as of April are already running higher than at the same time last year, and that more parents of 3-year olds, for which waitlists have generally been shorter than for younger children, are applying to place their children in licensed daycare centers than ever before. Meanwhile, muninka institutions, which are not formally certified by the government but are generally equal in quality to their ninka counterparts, will not be entirely free; instead, parents using these daycares will receive subsidies to defray a substantial part of the fees they pay. That has spurred more parents to opt for licensed daycares, which will be completely free: as a result, some muninka daycares are already closing. It’s expected that the new program will create much higher demand for licensed daycare places and that more parents will be eager to avail their children of this free service. Fewer noncertified daycare places may lead to longer waitlists in 2020, so the policy is having a distorting effect. Waitlists and the Financial Issue This situation highlights the close connection between daycare fees, be they high or low, and the number of children waitlisted for places at daycare facilities. Politicians, thinking they were doing families with preschoolers a good turn, vied to lower or completely eliminate fees, as will be the case starting later this year. Instead, though, the new program is leading to longer waitlists for daycare and increasing the burden on families with young children. The road to hell is indeed paved with good intentions. Actually, the waitlist issue itself has its roots in the fact that daycare fees are very low to begin with. Let me give you the example of the situation in Tokyo, based on what I observed when I previously served as a special advisor to Tokyo Governor Koike Yuriko for measures to shorten daycare waitlists. Fees for licensed daycares differ based on household income; monthly fees average around ¥20,000 to ¥30,000. On the other hand, monthly fees at noncertified daycares can easily be double that or more. Tokyo has numerous muninka daycares called ninshō facilities—daycares certified by the Tokyo metropolitan government that receive subsidies from the TMG or cities in greater Tokyo. While these facilities offer the same quality of care as licensed daycares, average monthly fees are over ¥65,000. Consequently, licensed daycares attract many more applicants because of their much lower fees, which means long waitlists for those facilities. Some say that the waitlist issue can be taken care of by increasing the number of licensed daycares to meet demand. But that is easier said than done, given the state of municipal finances. Operating costs for licensed daycares in cities in greater Tokyo run to ¥150,000 to ¥200,000 per month per child. Infant care, in particular, is very costly at ¥400,000 per month per child. In many municipalities, monthly per-child operating costs for public daycare facilities come to ¥500,000 to ¥600,000. Meanwhile, parents are charged only a fraction of this cost, and cities must use tax money to bridge the gap. One radical solution might be for municipalities to pay each family with the youngest children, up to the age of two—a group for whom waitlists are especially long—a direct monthly stipend of ¥200,000 so that those children can be looked after at home. That would certainly be less costly than the current system: no matter how affluent many cities in greater Tokyo are, financial constraints make it difficult for them to open more licensed daycares Daycare as a Form of Negative Income Redistribution Parents with children in licensed daycares focus mainly on the fees they pay; few probably realize that the service is heavily tax-supported. Those parents are in fact already receiving what could be called a “child-rearing subsidy” amounting to several hundred thousand yen per month, so they are the lucky ones. Meanwhile, parents with children in muninka daycares receive very low or no subsidies at all. And those who give up on trying to find daycare for their children and end up keeping them at home don’t receive a single yen in subsidies. This is not only unfair, it is a major failing of a welfare policy intended to help the weaker members of the community. The current system for assigning daycare places is score-based, with points assigned according to the need for daycare in each family. Selections are made in descending order of scores, with children from families with the highest scores selected first. Except in the case of low-income families receiving welfare support, the point system favors families with two parents working as full-time regular employees. This places parents who are nonregular employees at a disadvantage, and in cities with long daycare waitlists, many nonregular employee parents are forced to use muninka daycares or to look after their children at home. Generally speaking, regular employees enjoy considerably higher family incomes than nonregular employees. This means that under the current licensed daycare system, better-off families where the parents are regular employees receive generous subsidies while other families are left out in the cold. To me, this system, which supports the strong and disadvantages the weak, is truly perverse. Will the free preschool program do anything to improve the situation? It’s true that users of noncertified daycares will receive a certain amount in subsidies to help offset fees. But those with children in licensed daycares will not need to pay at all, and moreover, it is higher-income families, who pay somewhat higher fees, that will stand to benefit the most. The end result is worsened income distribution, since the money for free preschool will come from the consumption tax set to increase in October this year, a regressive taxation scheme that imposes a bigger burden on low-income earners. Subsidies for All What is the solution? If it proves politically impossible for the government to reverse its policy of funding free preschool through the consumption tax increase, I propose tweaking the program to keep unfairness to a minimum. The easiest way to do this would be to pay the money for free preschool directly to parents rather than channel it to cities or daycares. At the same time, part of the monies cities use to subsidize licensed daycares could be used to subsidize users instead, with the government paying each family with eligible children a child-rearing subsidy of ¥65,000 per month. Just taking this step would dramatically improve the situation. If fees for licensed daycares were set at ¥65,000 per month for all users, regardless of income, families could simply use the child-rearing subsidy to pay the daycare fee, essentially making daycare free. However, since the same subsidy would be paid to all parents of eligible children, not just licensed daycare users, but also parents using muninka daycares and kindergartens, and parents looking after their children at home, doing so would go a long way toward eliminating unfairness and inequality. Would that mean longer waitlists? Probably not. Able to charge ¥65,000 in monthly fees, noncertified daycares could be profitable while still offering quality childcare. Since users would be paying the same fees whether their children were in licensed daycares or not, many families might opt for the muninka option because of distinctive features or convenient services they offer. In other words, although constraints on building more licensed daycares would remain, the number of noncertified daycares could grow substantially under such an arrangement. Some may worry about the quality of care at these muninka facilities. In that case, they could be more closely regulated with passage of a law requiring that they meet the standards of Tokyo-certified ninshō daycares. This would be a common-sense measure, given that muninka daycares would now also be supported by tax money through the subsidies paid to users. Furthermore, some parents who placed their children in licensed daycares simply because the fees were low might opt to look after their children at home and keep the subsidy. Or even if they sent their children to kindergarten, they would still have money left over after paying kindergarten fees. Ultimately, the program would reduce the number of families wishing to use licensed daycares and could help reduce waitlists. The problem, of course, is where to find the money. I think it could come from gradually cutting back on the subsidies now being paid to licensed daycares. These facilities have a very high cost structure, so there is plenty of room for cutting expenses. As ninka daycares compete with their muninka and ninshō counterparts, licensed facility operators should learn from the private sector and reduce their operating costs. It might even be desirable for the latter types of daycare to replace licensed facilities if they aren’t cost-competitive. In fact, to do away with the unfair advantage of government-supported daycares over privately-run facilities, which stifles competition, all public daycares should be privatized. Continuing to give only licensed daycares special treatment simply isn’t fair. The new free preschool program should be seen as an opportunity to not just do away with the existing scattershot tax support but also to improve the daycare system. If the government can demonstrate that this is being done, the public may be more receptive to the coming increase in the consumption tax. Diaper rush: Conquering a $9 billion incontinence market no one wants to talk about BY RICHA NAIDU AND RITSUKO ANDO REUTERS https://www.japantimes.co.jp/news/2019/10/24/business/adult-diapers-9-billion-market/ Oct 24, 2019 CHICAGO/TOKYO – The time may not be far off when more adults need diapers than babies as the population grows older, potentially a huge opportunity for manufacturers of incontinence products — if they can lift the stigma that has long constrained sales. The market for adult diapers, disposable underwear and absorbent pads is growing fast, up 9 percent last year to $9 billion, having doubled in the last decade, according to Euromonitor. But manufacturers like market leaders Essity and Kimberly-Clark Corp. reckon only half of the more than 400 million adults likely to be affected by weak bladders are buying the right products, because they are too embarrassed. Companies are trying various methods to change attitudes, including making products more discreet, avoiding terms like diapers or nappies, and placing items in the personal care aisle, next to deodorants and menstrual pads, rather than in the baby products section. They are also trying to normalize discussions around the subject through advertising. In Japan, where adult incontinence products have outsold baby diaper sales since around 2013 due to a rapidly aging population and low birthrate, Used in the fourth paragraph. “Adults incontinence products have outsold baby diaper sales” shows that in Japan, the diapers that conquer their market are not baby diapers but adults diapers. This is due to the amount of elderlies that keep increasing more than the birth of newborn babies each day. market leader Unicharm Corp has adopted the phrase choi more in its advertising, which translates as “lil’ dribble,” to make light of the problem. “What we are doing is trying to let people know that incontinence, even among young people, is normal,” said Unicharm spokesman Hitoshi Watanabe. The company is focusing particularly on people with mild bladder issues where it sees the biggest growth as people lead more active lives. Unicharm’s sales of absorbent pads and liners that target this market were up 8 percent last year. In the U.S., market leader Kimberly-Clark has this year given its 35-year-old Depend brand a makeover, introducing thinner, softer and more fitted products that can be worn discreetly, in an effort to make them more acceptable. The changes are just the latest in a decade-long attempt to win over consumers, which started with manufacturers dropping the “diaper” label, to loosen the association older customers might have with a loss of control in their life. Yet it is still difficult for companies to persuade people they should buy specially made incontinence products. “People keep the fact that they have incontinence secret from their loved ones, from their husbands, brothers and sisters — this is a deep secret for many consumers and yet it’s just a fact of life, it’s a physiological reality,” said Fiona Tomlin, who leads Kimberly-Clark’s adult and feminine care division. Manufacturers have been particularly keen to win over women, who are more than twice as likely as men to experience bladder weakness, due to childbirth. Kimberly-Clark has reached out to them directly over the years in light-hearted ad campaigns featuring actresses Whoopi Goldberg and Kirstie Alley. Kimberly-Clark’s Poise brand is aimed at younger women like Ellie Foster, a 31-year-old from Maine, who has struggled with leaks since having her first child 1½ years ago but is too embarrassed to buy products that might help her. “At first I did, but it was definitely weird picking out adult diapers to wear,” said Foster. “You feel like you’re in the old lady section.” Sweden’s Essity, the global industry leader, is also trying to reach a younger audience with its Tena brand and a new line of black, low-rise disposable underwear called Silhouette Noir. The ad’s tagline reads: “Secret’s out: 1 in 3 women have incontinence.” Around 12 percent of all women and 5 percent of men experience some form of urinary incontinence, although conditions vary from mild and temporary to serious and chronic, according to the Global Forum on Incontinence, which is backed by Essity. Essity said it tries to package and market its products in a way that avoids associations with aging. “Designing products and packaging it as feminine and discreet as possible for females and as masculine and discreet as possible for men helps,” said Ulrika Kolsrud, president of Essity’s health and medical solutions. Getting the message across to potential customers can sometimes be a tricky path to tread. A few years ago, SCA — from which Essity was spun off in 2017 — mailed samples of its products to Swedish men above 55, only to receive a barrage of complaints. But efforts are starting to pay off. Five years ago, adult incontinence products were used by around 13 percent of the target adult female audience in France and the U.K. and that is now closer to 20 percent, according to research firm Kantar. That does, of course, leave huge potential for further sales growth. As Kolsrud puts it: “If incontinence was a country, it would be the third-largest country in the world.