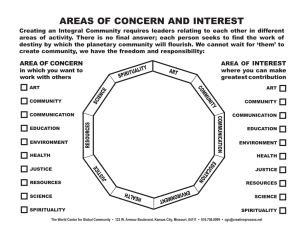

Understanding Spirituality: An Indian Interpretation The enchanting land of Bharat (India) has held an aura of allure and mysticism that is sparkling. While largely ignored by her Western counterparts, the practices and traditions that originated here are abysmal. Even more crucial is the fact that though reduced, the ancient practices of spirituality are still widespread in the lives of Indian people. India is the cradle of spiritualism where several schools of thoughts emerged such as Vedanta, Yoga, Nyaya and Vaisheshika (Goswami, 2017). Over the several thousand years, an overarching metatheoretical framework developed which made no distinction between philosophy, religion and spirituality binding them together in a mosaic representing the Indian ethos. The consequence is, today it is common for a person to intermingle spirituality with religion and in a way, it is true; religion does allow people to gain spirituality. It was the abstractness of spirituality paved the way for the birth of religions (AYUSH, 2015). To understand it better consider spirituality at one end of the spectrum and religion at another end and philosophy as the thread that binds them together. Therefore, while spirituality is the theoretical approach to truth or divine power, religion is the practical approach to it (Goswami, 2017) and both run on a loosely similar philosophy. Figure 1: Representation of interconnection between Spirituality, Philosophy and Religion Spirituality has become increasingly popular over the years, especially in the West, but the problem lies in the fact that several Indians have forgotten their legacy after the increasing influence of colonial rule and modernization while Western thought finds it challenging to process the complexity spirituality holds through their objective lenses of positivism. While the concept is no longer considered unscientific the gap present manifests in the attempt to evaluate and classify spirituality. Further, as I mentioned before, the three concepts of spirituality, religion and philosophy have lost their distinction between them over the years in Indian thought. The consequence is that understanding spirituality becomes difficult. Therefore, the attempt is to explore the meaning of spirituality according to ancient Indian texts. How have Western scholars defined Spiritualism? The concept of spirituality begins from Judeo-Christian tradition with little distinction between it and the religion (Jacobs, 2013). I am referring to Christianity as it is the most followed religion among the Western countries. In 1989, Schnieders reached the word, ‘pneumatikos’ meaning person under the influence of the Spirit of God (Oman, 2013) as the root of the word ‘spirituality’. Another understanding comes from the Hebrew word ‘ruach’ which means spirit. Jacobs (2013) describes spirituality, as “something that broke free from the restricting confines of association with formal religion.” This separation in the West between religion and spirituality, especially in concern with religion Christianity is traced back to the work of psychologist Carl Jung (Benner, 1988 as cited in Jacobs, 2013). For example, Love (n.d.) in his article, “Differentiation Spirituality from Religion” gives a detailed background, definition and understanding of the two constructs and how they are different. Further, he explains religion as an external phenomenon while spirituality as an internal. The distinction has also been given by several other scholars (see Woods & Ironson, 1999; Koenig et al., 2001 as cited in Rao, 2011). Religion is ascribed to rules, conducts, traditions and beliefs developed by humans themselves while spirituality moves away from these, where the quest is to reach the higher being and fulfilment (Jacobs, 2013; Love, n.d.) through connectedness which occurs intra, inter and trans-personally (Meezenbroek, Garssen, Berg, Dierendonck, Visser & Schaufeli, 2010). However, it is also expressed that the two constructs have similarities (Love, n.d.). One view is that spirituality forms an outer circle which encircles the smaller circles of several religions 2 (Koenig et al., 2001 as cited in Rao, 2011). The other view holds religion as the outer circle which encircles spirituality (Miller & Thoreson, 1999 as cited in Rao, 2011). Thus, what is observed is a conflicting view of the relationship between spirituality and religion. Further, little distinction is seen between the two in empirical studies (Rao, 2011) often cited as R/S. Therefore, a clear disagreement exists whether the two are the same or different. The efforts to understand spirituality in Western studies have increased approximately 40-fold by the early 2000s (Oman, 2013). This indicates the revived interest in a once forgotten, unscientific and supernatural concept. But many view it from the confines of scientific view and have divorced several spiritual practices from their roots while adopting eastern practices. Moreover, in qualitative research on ten spiritual questionnaires, it was found that they could not capture the essence of spirituality, failed to discriminate spiritual facets from that of psychological facets such as personality or well-being and the items often had inconsistency (Meezenbroek, Garssen, Berg, Dierendonck, Visser & Schaufeli, 2010). Do similarities exist in the Western and Eastern perspective of Religion and Spirituality? It is imperative to note that when I talk about a Western understanding of spirituality, I do not refer to the scientific philosophy that emerged but spirituality that connects to the religion. Despite differences that have been cited repeatedly between the concepts, one cannot deny the fact that similarities also exist. Further, religion was formed to gain spirituality from a practical path. Especially, for a common man who did not have the time or resources to gain and understand spirituality in its complexity. Unfortunately, as time progressed from antiquity religions became more and more orthodox and the practices once formed to connect with God, or the higher power became increasingly adulterated. In modern times, as a result, it is observed that religion is often viewed in a negative light by the newer generations. Spirituality, on the other hand, is now gaining popularity, especially in the West. Rao (2011) states that Eastern and Western perspectives on religion and spirituality agree that the two merge at one point- sacredness. He further elaborates that the ‘scared’ alludes to several things such as God, divine power, formless entity and so on (Rao, 2011). And the goal is to attain 3 transcendence (Rao, 2011, Love, n.d.) in both West and East. Further, both consider religion as external and spirituality as internal. Spirituality: An ancient Indian concept The philosophy that emerged in the land of India is believed to be much older than that which emerged in ancient Greece. And the difference between the two is while Indian philosophy was an amalgamation of scientific reasoning, spirituality, and religion to some extent. Western philosophy solely rested on objectivity and scientific pursuit. Consequently, the slow acceptance of spirituality in the West can be alluded to the complex systems of philosophies that existed in the subcontinent. India has not one but eight different systems that all have their own understandings and teachings on spirituality. Further, it is comprehensive, holistic, and cyclic. The word philosophy is known to be first used by Greek Philosopher, Pthyogorus. The two words- ‘philo’ which means love and ‘sophia’ which means wisdom come together to form the popular word, ‘philosophy.’ From an Indian perspective, the Sanskrit word, ‘darśana’ translates into seeing or experience (Prabhavananda, 2019). However, this seeing or experience has a deeper meaning- immediate perception. Does that mean absorbing everything through our senses at a given time? No. Darśana according to Indian epistemology refers to super-sensuous transcendental (Prabhavananda, 2019) i.e., witnessing the Absolute truth- the experience of Brahman transcending time, space, and causation (Yvas, 1982 as cited in Gill, 2006). Therefore, experiencing spirituality means the experience of spirit (ātman) or spiritual consciousness permeating into the all of cosmos along with encompassing every human pursuit (Rao, 2011). Vedas The source of all in Indian understandings comes from the Vedas, the Brahmans, the Aranyakas, the Upanishads and the two great Indian epics of Ramayana and Mahabharata. The Vedas it is believed date back to at least 2000 B.C. and passed down through oral tradition. This is the time when you won’t find the followers of ‘Sanatan dharma’, today known as followers of Hinduism, worshipping idols (murtis); but the eternal order (formless) itself revealed by the Vedas. 4 The Vedas comes from Sanskrit root word, ‘Ved’ meaning ‘knowledge’ and is believed to be a non-human (apaurusheya) creation revealed to the Risis, the seers of truth (Kumar & Choudhary, 2020). It is held in the highest regard as the source of knowledge that is sublime and scientific. Historians believe that the Vedas were written down around 5-6th century B.C. The four-great works of Vedic literature Rig Veda (written in honour of deities, concepts around death, life, Atma, Paramatma), the Yajur Veda (hymns to perform Vedic Yajnas), the Sama Veda (ceremonial texts, melodies, and chants), and the Atharva Veda (deals with magic, tantra-mantra, spirits, and medicinal resources of plants etc.) (Roy, 2016; Vyas, 2016; Kumar & Choudhary, 2020). Upanishads “To know Brahman is to be Brahman.” To understand, Upanishads I quote Radhakrishnan (as cited in Jacob, 1975) known for his utmost clarity and work on them. “Though in some sense the Upanishads are the continuation of the Vedic religion, they are in another sense a strong philosophical protest against the religion of the Brahmanas. It is in the Upanishads that the tendency to spiritual monism, which, in one form or another, characterizes much of Indian philosophy, was first established whose intuition rather than reason was first recognized as the true guide of ultimate truth.” The statement makes few things clear: 1) Upanishads present the ancient Indian understanding of spiritualism which is profound and enlightening; 2) They are philosophical interpretations of Vedas but a revolt against the Brahmanas that rose from Vedas; 3) It talks about the ultimate truth which is considered as the end goal in Indian thought; 4) The ultimate truth lies within us. The texts of Upanishads are believed to bring closure to the Vedas and therefore, are also called Vedanta (end of Vedas). Prabhavananda (2019) states another interesting interpretation of ‘anta’ which means the final goal- the highest wisdom (transcendence). Today, a total of 108 Upanishads are extant. Curiously, an undertone of mystery revolves around these ancient sacred texts. Nobody knows when did they emerge, who wrote them or were they more in number than 5 what exists today? (Prabhavananda, 2019) The Upanishads are held in high regard among the followers of Sanatana dharma as they allow an average person to connect more to their philosophy, religion, and connect with the formless. The word ‘Upanishad’ comes from Sanskrit words which together translates as sitting near the spiritual guru to receive and gain the secret spiritual knowledge (Roy, 2016; Prabhavananda, 2019). It is imperative to realize that the Upanishads though a driving force behind the Indian thought, is far from belief. They move away from the ritualistic and sacrificial traditions of the Vedas yet retains the scientific basis. The sacred texts deal with the metaphysical and spiritual aspects which are abstract at their core (posing a challenge to appreciate them from an objective lens). However, Upanishads were just as scientific as their source texts- the Vedas. In the scientific archive, Upanishads took an unparalleled turn towards the medium of knowing- the mind (Easwaran, 2007). The very concept of consciousness which modern science has still not deciphered, forms the very basis of Upanishads. When Philosophy was just rising in the West, the sages in India dealt with a complex understanding of dreams, wakeful state, self-‘I’ and found their answer in consciousness (Brahmavidya)- the science of the Supreme (Easwaran, 2007). The absolute teachings and curiosity these ancient men held in understanding these composite concepts which scientists today are still trying to grasp shows the significance of these texts today as they were in antiquity. Core Concepts of Upanishads Upanishads dealt with questions that captured the fervid aspiration to discover the central principles of the world and human experience (Easwaran, 2007). In doing so the sages came across concepts and experiences which are difficult to understand and believe in today’s modern world. Yet one cannot deny the existence of these great men and their quest for knowledge which though slowly, is being discovered again. Brahman and Ātman The concept of Brahman refers to the formless essence present in every being, things, cosmos, and Gods (Easwaran, 2007). Thus, called as the Supreme reality- the abstract power or the 6 Ultimate reality. Brahman moves away from the practical associations, it cannot be known or explained (Pandit, 1988). Therefore, understanding Brahman can be challenging initially. Pandit (1988) gives a comprehensive understanding of Brahman. Brahman is satyam: truth- idea of existence viewed objectively; absolute reality, jnanam: knowledge- consciousness viewed objectively, anantnam: infinite- idea of bliss viewed objectively; freedom (Pandit, 1988). Further, to give a wholistic picture I quote, Pandit (1988): “Regarded from the view of Time, Brahman is Eternity or Immorality; regarded from the view of Space, Brahman is Infinity or Universality; regarded from the view of Causality, Brahman is absolute Freedom.” The concept of Brahman connects with the concept of Ātman (true self/ spirit). Ātman is the true self which is not adulterated by the Ego (ahaṁkāra). It is immortal, fearless (Prabhavananda, 2019) and indiscernible unlike the empirical body. It is the internal controller (antaryāmin) beyond all of existence with no individualistic characteristics (Lindquist, 2019). Therefore, knowing of the true self connects with knowing of Brahman- transcendence which resides in everyone. The Brahman and the Ātman becomes one and the same (advaita). “so’ham and aham brahmāsmi” (He am I and I am Brahman, the Eternal) The distinction between the subject, object and the act disappears, between knower, known and act of knowing disappears (Rao & Paranjpe, 2016). The disparity of dichotomies and polarities seen while understanding the man’s nature seen in the Western thought, vanishes (Jacob, 1975). The empirical self thus ceases and the higher knowledge (parāvidyā) which is neither subjective nor objective attained (Prabhavananda, 2019) i.e., state of moksha. Ego (Ahamkara) and Tainted reality A nexus model of body, mind and consciousness helps to understand the complex Indian thought (Rao & Paranjpe, 2016; Rao, 2011). Mind is the physical entity which interfaces with both, the physical side (brain and empirical reality) and the subjective side (consciousness/spirit) at two 7 polar ends. Unfortunately, the mind is more connected to the brain (cognitive operations) forming the mind-body nexus (transactional part). The mind (manas) manifests the Ego (ahaṁkāra- empirical self) through mind-body interaction walking humans down the path of ever-increasing attachments, desires, cravings and ultimately anguish and sufferings. The more one identifies with Ego (ahaṁkāra), the more ignorant (avidyā) one becomes; always looking at the tainted reality (empirical reality), never reaching the true self (ātman) and the ultimate reality (brahman). Therefore, to reach the true self (ātman), the relegation of ego is significant to experience consciousness-as-such (Rao, 2011; Jacob, 1975). Mind-Consciousness and Moksha Another nexus that exists apart from mind-body, is mind-consciousness (transcendental part). Curiously, mind according to Upanishads consists of subtler forms of matter making it possible for the light of consciousness to reach it for reflection of contents and mind also has a passive approach to consciousness (Rao, 2011). Therefore, the mind-consciousness nexus allows the trans-cognitive processes to occur for consciousness to be realized in the mind (Rao, 2011). The realization of true self is called ‘moksha’ (samadhi/nirvana) as it liberates self from the conditions of time, space (Easwaran, 2007), existential anguish and sufferings (Rao, 2011). Rao and Paranjpe (2016) describe moksha as, “For the one who realizes reality in its true form, the sensory knowledge we have of the world appears as nothing but an illusion, as a dream appears on waking.” It means achieving transcendental knowledge (parāvidyā). It is either attained during the course of life or at death (Prabhavananda, 2019). The realization of moksha means realization of true self (ātman) and thus, realization of consciousness-as-such (brahman), the transcendental knowledge. Therefore, the path to spirituality lies in moksha. But what is the process of achieving this highest state of spirituality? Especially when the Ego (ahaṁkāra) is unfortunately, blocking the experience of this transcendental reality. 8 Relegating the Ego: Path to Moksha The journey to moksha faces the block of Ego (ahaṁkāra) which controls the being and renders it deeper into the world of empirical reality. To overcome this illusion (maya) there are two pathways. Therefore, one pathway involves meditation (nididhyasana) and other involves walking down the path of knowledge (jñāna mārga), devotion/ faith (bhakti mārga) and work (karma mārga) which are often associated with Hindu religion. However, it is also significant to remember that each school of thought that came to be had developed their own significant meaning and names for moksha and diverse ways to achieve it (Rao & Paranjpe, 2016). The practice of meditation allows for deconditioning from the ego bounds, facilitates effective learning and gains control over mind functions (Rao & Paranjpe, 2016). The act of meditation involves deep intense inward focus where the empirical world ceases to be important and the depths of consciousness can be reached. Thus, normal cognitive functions stop interfering and the mind opens to knowledge, wonders and bliss. The practices of Yoga Sutras of Patanjali are one such medium which helps to control the fluctuating mind states and reach the consciousness-as-such (Rao & Paranjpe, 2016). Conclusion Spirituality, therefore, is a concept common to both West and East. However, a sheer difference in its understanding and complexity exists. Today, Western societies have accepted the importance and validity of spirituality. But understanding spirituality is still in its primitive stages. Further, though scholars have attempted to define and evaluate spirituality, an obvious lack of consensus along with comprehension is seen. An obfuscation is also observed around spirituality and religion. They both are differentiated and coalesced according to convenience. The attempts at measuring spirituality through self-report methods appear questionable. And despite the acceptance of Eastern spirituality practices, a clear misconnection with the process and thoughts is present. On the other hand, though a birthplace of spirituality, the major Indian population has lost touch with its ancient roots and knowledge due to the aftereffects of colonization and escalating 9 capitalization. Today, many consider religion and spirituality the same despite being differentiated concepts in the Indian texts. Many youngsters are seen impassive towards these texts holding profound knowledge. And therefore, despite being home to such intense knowledge, its significance and appreciation is lost. Especially in concern to Indian Psychology which rests on ancient practices and knowledge. It is unfortunate that the psychology in India is a mere replication of that taught in West (Rao, 2011). A strong need exists in Indian Universities to foster young minds to dive in these concepts and appreciate them from an Indian viewpoint. For this, it is imperative to recognize the scientific basis of these texts and developed practices. Further, view spirituality separately from the religion of hinduism because religion came into the picture much later. And realize that spirituality is a complex concept which cannot be suppressed in the restraints of objectivity. It is both objective and subjective. Most importantly, study with an open mind because a closed off mind will only hamper the understanding and acceptance. The source of spirituality lies in the Upanishads. It is a difficult concept as it gets entangled with religious concepts apart from being abstract. It deals with intertwined notions of formless, true self, liberation, paths and practices, several schools of thought that emerged dealing with Supreme form and spirituality disparately. It also brings forth scientific understandings which further, poses difficulty. Thus, spirituality brings together the supernatural and science together. To conclude the knowledge of spirituality is like an old photo album lying in the back of the closet, significant yet overlooked, close to heart yet neglected, waiting to be discovered. References AYUSH. (2015). Spirituality and Health. National Health Portal India. Retrieved from https://www.nhp.gov.in/spirituality-and-health_mty Gill, A. (2006). In search of Intuitive knowledge: A comparison of Eastern and Western Epistemology. Simon Fraser University, 1-189. Goswami, A. (2017). Spiritualism in India. The Pioneer. Retrieved from https://www.dailypioneer.com/2017/sunday-edition/spiritualism-in-india.html 10 Jacob, T. R. (1975). Concept of Self in Indian Thought. Masters Dissertation, Marquette University, Wisconsin, USA. Retrieved from https://www.marquette.edu/library/theses/already_uploaded_to_IR/jacob_t_1975.pdf Jacobs, A. C. (2013). Spirituality: History and contemporary developments – An evaluation. Koers – Bulletin for Christian Scholarship, 78(1). Retrieved from http://dx.doi.org/10.4102/ koers.v78i1.445 Kumar, S., & Choudhary, S. (2020). Ancient Vedic Literature and Human Rights: Resonances and Dissonances. Cogent Social Sciences, 7, 18. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311886.2020.1858562 Lindquist, S. E. (2019). "Transcending the World" in World Literature: The Upanishads. In K. Seigneurie (Ed.), A Companion to World Literature. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. DOI: 10.1002/9781118635193.ctwl0021 Love, P. G. (n.d.). Differentiation Spirituality from Religion. Florida State University. Retrieved from https://characterclearinghouse.fsu.edu/article/differentiating-spirituality-religion Meezenbroek, E. d. J., Garssen, B., Berg, M. v. d., Dierendonck, D. v., Visser, A., & Schaufeli, W. B. (2010). Measuring Spirituality as a Universal Human Experience: A Review of Spirituality Questionnaires. Journal of Religion and Health, 51, 336-354. Retrieved from https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10943-010-9376-1 Oman, D. (2013). Defining religion and spirituality. In R. F. Paloutzian & C. L. Park (Eds.), Handbook of religion and spirituality (2nd ed., pp. 23-47). NY, New York: The Guilford Press. Retrieved from https://books.google.co.in/books?hl=en&lr=&id=GS8cBQAAQBAJ&oi=fnd&pg=PA23 &dq=spirituality+according+to+western+scholars&ots=AQx6iL69Vu&sig=mfol8m_mh_ n_yhkU6_rGlu7xv8s&redir_esc=y#v=onepage&q=spirituality%20according%20to%20w estern%20scholars&f=false Pandit, M. P. (1988). Upanishads: Gateways of Knowledge (1st ed.). Wilmot, WI: Lotus Light Publications. Retrieved from https://www.google.co.in/books/edition/Upanishads/Dnh_qHPfe4IC?hl=en&gbpv=1 11 Prabhavananda, S. (2019). Spiritual Heritage of India (1st ed., Vol. 10). NY, New York: Taylor & Francis. Retrieved from https://www.google.co.in/books/edition/_/hu4xvgEACAAJ?hl=en&sa=X&ved=2ahUKE wj52ILkjrXwAhXNzjgGHcTAA_0Q8fIDMBV6BAgGEA0 Rao, K. R. (2011). Indian Psychology: Implications and applications. In R.M. J. Cornelissen, G. Misra, & S. Verma (Eds.), Foundations of Indian Psychology: Theories and Concepts (Vol. 1, pp. 7-26). Noida, India: Pearson. Rao, K. R., & Paranjpe, A. C. (2016). Psychology in the Indian Tradition. NY, New York: Springer. DOI 10.1007/978-81-322-2440-2 Roy, S. (2016). Vedic literature- A significant literature of ancient India: An introduction. International Journal of Applied Research, 2(6), 161-163. Retrieved from https://www.allresearchjournal.com/archives/2016/vol2issue6/PartC/2-5-122-406.pdf The Upanishads (E. Easwaran, Trans.; 2nd ed.). (2007). Tomales, CA: Nilgiri Press. Retrieved from https://www.google.co.in/books/edition/The_Upanishads/CcnJAAAAQBAJ?hl=en&gbpv =1 Vyas, A. (2016). Indian Philosophy and The Universe [United Nations/Costa Rica Workshop on Human Space Technology]. Retrieved from http://www.unoosa.org/documents/pdf/psa/hsti/CostaRica2016/10-2.pdf 12