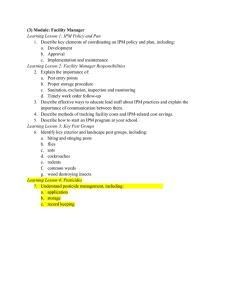

MenzleretalImplementationofIPMstrategiescontraintsandmotivationstochangefarmingInternSymponIPMinOSR2006Gttingen

advertisement

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/281117043 Implementation of IPM strategies: constraints and motivations to change farming practices Conference Paper · April 2006 CITATIONS READS 0 429 8 authors, including: Heikki Hokkanen Wolfgang Buechs University of Helsinki Universität Hildesheim 91 PUBLICATIONS 3,711 CITATIONS 106 PUBLICATIONS 817 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE SEE PROFILE Zdzislaw Klukowski Anne Luik Wrocław University of Environmental and Life Sciences Estonian University of Life Sciences 34 PUBLICATIONS 438 CITATIONS 32 PUBLICATIONS 218 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE SEE PROFILE Some of the authors of this publication are also working on these related projects: Pesticide residues in food and environment. Organic food quality View project Migration and early population development of aphids (Hemiptera: Aphididae) in winter cereals View project All content following this page was uploaded by Wolfgang Buechs on 21 August 2015. The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file. Implementation of IPM strategies: constraints and motivations to change farming practices I Menzler-Hokkanen, H M T Hokkanen University of Helsinki, Box 27, FIN-00014, Helsinki, Finland Email: ingeborg.menzler-hokkanen@helsinki.fi W Büchs BBA, Messeweg 11 / 12, D-38104 Braunschweig, Germany Z Klukowski, Agricultural University of Wroclaw, 50-205 Wroclaw, Cybulskiego str. 32, Poland A Luik Estonian Agricultural University, Kreutzwaldi 64, Tartu 51 014, Estonia C Nilsson Swedish University of Agriculture, PO Box 44, S-230 53 Alnarp, Sweden B Ulber Georg-August University Göttingen, Grisebachstraße 6, D-37077 Göttingen, Germany I H Williams Rothamsted Research, Harpenden, Hertfordshire, AL5 2JQ, UK INTRODUCTION The adoption rate of integrated pest management (IPM) techniques by growers in large-scale field crops has been disappointingly low, whereas in protected crops they have gained spectacular acceptance and success (van Lenteren, 2000). Of the total growing area of cereals in Europe, only 10% is considered to be under IPM, but this proportion is even less for maize (4%) and field vegetables (5%) (van Lenteren, 1993). Data for oilseed rape (OSR) were not included in that study, but can be expected to be close to that of cereals. Interestingly, 50– 60% of European OSR growers currently consider by themselves that they practise IPM (Menzler-Hokkanen et al., 2006) – a clear contrast with the earlier data, indicating possibly a more liberal interpretation of the IPM concept rather than a true expansion in the adoption of IPM by growers. As OSR is a very large crop in the EU, second only to the cereals in cropping area, and because it is one of the most plant-protection intensive of the major crops, we decided in the MASTER project to analyse the European growers’ attitudes to IPM, and motivations for and constraints to changing their growing practise. This we hope will help in designing improved policy measures to support government efforts to encourage IPM adoption for the crop throughout Europe. MATERIALS AND METHODS A questionnaire for OSR growers concerning their current cropping practices in the 2002–2003 growing season was disseminated in each of the six partner countries. In total, 1,005 replies were obtained for analysis. The main survey produced 216 responses from Germany, 179 from Finland, 165 from Estonia, 154 from Poland, 136 from Sweden, and 115 from the UK. An additional 40 replies were obtained from pilot studies in Finland and Estonia. Random postal surveys (Finland, Estonia, UK partly) produced return rates of from 25% (UK) to 46% (Estonia), while targeted surveys provided higher returns: 61% for Germany, 65% for Sweden, and ‘over 90%’ for Poland. Different sampling methods had to be used, because the ideal method of random sampling in each country was possible only in Finland and Estonia, where centralised data on growers are available. We do not believe that the slight differences in the sampling resulted in any inherent biases; in fact, analysis of the data showed that they are robust and reliable. RESULTS AND DISCUSSION Conventional OSR growers were asked whether certain policy or market mechanisms would encourage them to change to IPM. The clear favourite in replies from all countries was a higher price for the seed (Table 1a). Only 1% of farmers from Estonia, and only 3% of UK and 4% of Polish and German farmers would not at least consider changing farming practice. However, an astonishing 14% of Finnish farmers replied ‘no’ to this question: they would not change to IPM even if it gave them a higher price for the seed (Table 1a). In general, farmers in Germany and Poland appear to be more ‘price sensitive’ than those in Finland or Sweden. The second most favoured measure was special economic support for IPM production; in Germany, however, this was a lesser incentive than higher seed price, whereas in other countries these two were almost equally selected (data not shown here). If changing to IPM required increased crop inspection, but production costs remained the same, many more farmers would hesitate to change. Poland is here a clear exception: 64% of conventional farmers would still change, and only 3% replied ‘no’ (Table 1b). A similar question specifying a requirement to count insects in traps once or twice, produced similar results, but reduced the attractiveness to change still further (Table 1c). An interesting difference, however, between German and Polish responses (Table 1b and 1c) is that while German farmers did not favour increased crop inspection, they did not reject counting insects in traps. For Polish farmers the result was the opposite. This difference probably reflects the greater familiarity of German than Polish farmers with the concept of placing yellow water traps in their OSR fields; such traps are used more routinely in Germany than in Poland. Based on survey responses, farmers did not yet fully trust the usefulness of a computer-based decision support systems (Table 1d). Even a ‘reliable computer decision support system’ would apparently not convince most farmers to change to IPM; however, about 50% did reply ‘maybe’, indicating that they would be open to adopt such a system if convinced of its value first (Table 1d). Table 1. OSR farmers’ replies to the question: Would you change your pest management if: (a) this gave you a higher market value for your product? Estonia Finland Germany Poland Sweden UK Proportion (%) of replies (by conventional growers) ‘Yes’ ‘Maybe’ ‘No’ 64 35 1 38 49 14 88 7 4 80 16 4 56 38 7 63 33 3 (b) crop inspection increased but costs remained the same? Estonia Finland Germany Poland Sweden UK Proportion (%) of replies (by conventional growers) ‘Yes’ ‘Maybe’ ‘No’ 22 65 12 26 53 21 17 55 29 64 33 3 38 49 14 36 50 14 (c) you had to count insects in traps once or twice? Estonia Finland Germany Poland Sweden UK Proportion (%) of replies (by conventional growers) ‘Yes’ ‘Maybe’ ‘No’ 17 55 28 20 57 23 46 34 19 43 40 17 36 40 24 39 50 11 (d) you had a reliable computer decision support system? Estonia Finland Germany Poland Sweden United Kingdom Proportion (%) of replies (by conventional growers) ‘Yes’ ‘Maybe’ ‘No’ 21 59 20 22 51 27 36 45 19 46 38 16 24 48 28 32 43 25 Another set of questions elaborated further the farmers’ readiness to change their practices (details not shown here). Questions relating to the ‘stick-approach’ included increased prices for insecticides, as well as a ban on broad-spectrum insecticides. It appeared that this approach would work better in Poland and Estonia, than in Germany or Finland, although everywhere, the carrot approach was preferred. Estonian and Polish farmers appear surprisingly well educated in questions relating to IPM components and the related ecological questions, generally agreeing with the experts better than farmers from the other surveyed countries (Menzler-Hokkanen et al., 2006). Also, their readiness to adopt IPM techniques appears much higher than that of the farmers from other countries. Positive economic incentives (e.g. higher product prices, special support for IPM) were favoured in all countries, but also the ‘stick-approach’ (e.g. higher prices for pesticides, narrower selection of pesticides) might encourage farmers in Poland and Estonia more than those in other surveyed countries. Maybe surprisingly, the attitude responses were almost never affected by variables such as the age group of the farmer, or by the size of the farm. The only exception appeared to be among Estonian farmers: older farmers were less willing to change their practices than young farmers – in other countries there was no difference at all based on age group. Quite surprisingly, in all countries, a group of 10–20% of farmers would not even consider starting to use IPM, even when it would improve their profits and would not cause any more work than their current conventional practise, BUT if at the same time on the crop there would be a larger number of pests than before. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Support from the EU-project MASTER: MAnagement STrategies for European Rape pests (QLK5-CT-2001-01447) is gratefully acknowledged. However, without the cooperation of 1,005 OSR growers as respondents to the survey, and the help of many federal and regional agricultural officers in the six survey countries, this study would not have been possible. REFERENCES Lenteren J C van (1993). Integrated pest management: the inescapable future. In Modern crop protection: developments and perspectives, ed. J C Zadoks, pp. 217-225. Wageningen Press: Wageningen. Lenteren J C van (2000). A greenhouse without pesticides: fact or fantasy? Crop Protection, 19, 375-384. Menzler-Hokkanen I; Hokkanen H M T; Büchs W; Klukowski K; Luik A; Nilsson C; Ulber B; Williams I H (2006). Oilseed rape growers’ knowledge of and attitudes towards IPM. CD-ROM Proceedings of the International Symposium ‘Integrated Pest Management of Oilseed Rape Pests’, Göttingen, Germany, 3-5 April 2006. View publication stats