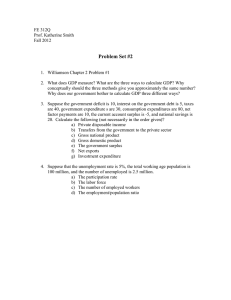

lOMoARcPSD|9845003 EC140 1st Midterm Text Notes Introduction to Macroeconomics (Wilfrid Laurier University) StuDocu is not sponsored or endorsed by any college or university Downloaded by Ali Azim (azim7550@mylaurier.ca) lOMoARcPSD|9845003 Chapter 19 - What Macroeconomics is All About 19.1 - Key Macroeconomic Variables National product = national income ← by definition National Product- most comprehensive measure of a nation’s overall level of economic activity - Value of a nation’s total production of goods and services - Also referred to as o utput National Income Aggregation - add up values of different goods & services produces - Q*P = $ value of production of each good → Nominal national income(current-dollar national income) - Sum = quantity of total output (national income) m easured in $’s - Change in NNI can be caused by physical quantities or prices sold - Real national income(constant-dollar national income) -calculate extent of change - Current output measured at constant prices - sum of quantities valued at prices that prevailed in base period - Prices held constant → changes in real national income of different years only changed in quantities Recent History- g ross domestic product (GDP) → most commonly used measures of national income - GDP can be measured in either real or nominal terms (focus on real) - Path of r eal GDP (increased by over 4 times since 1965 → substantial economic growth) Shows considerable year-to-ear fluctuations in growth rate of GDP Real national income produced by Canadian economy since 1965 (i) → s hort-term fluctuations around the trend - Overall growth dominates real GDP series, so fluctuations are hardly visible - However, in (ii), growth of GDP has never been smooth (ii) → annual % change over the same period Downloaded by Ali Azim (azim7550@mylaurier.ca) lOMoARcPSD|9845003 - - Canadian GDP shows 2 kinds of movement Major movement - positive trend that increased real output by approximately 4 times since 1965 → l ong-term economic growth Recessions- periods where GDP falls Characteristics of both l ong-run trends and s hort-run fluctuations Business cycle- continual ebb and flow of business activity that occurs around the long-term trend - Ex. a single cycle will usually include an interval of quickly growing output, followed by an interval of slowly growing or even falling output - May last for several years - All business cycles are different - variations occur in duration and magnitude - Some expansions are long and drawn out, while others come to an end before high employment and industrial capacity are reached - Fluctuations are similar enough that it’s useful to identify common factors Potential Output and the Output Gap - National output(or income) represents what the economy a ctually produces - Potential output: The real GDP that the economy would produce if its productive resources were fully employed - Potential Output (Y*): estimated using statistical techniques - Actual Output (Y): measured directly - Often disagreement among researchers because of different estimation approaches - Output gap- difference between potential and actual output (Y - Y*) - Y < Y*: R ecessionary gap - Market value of goods and services that aren’t produced - Economy’s resources not fully employed - Y* < Y: I nflationary gap - Market value of production in excess of what the economy can sustainably produce - Workers may work longer hours than normal or factories may operate an extra shift - Upward pressure on wages and prices Applying Economic Concepts Trough- unemployed resources and a level of output that’s low in relation to the economy's capacity to produce - Substantial amount of unused productive capacity - Business profits low (negative for some individual companies) Downloaded by Ali Azim (azim7550@mylaurier.ca) lOMoARcPSD|9845003 - Predicting economic prospects in the near future isn’t clear → many firms unwilling to make new investments due to r isk Recovery- economy’s movement away from trough - Run-down or obsolete equipment is replaced - Employment, income, and consumer spending all begin to rise → expectations become more favourable - Risky investments may be undertaken as firms become more optimistic about future business prospects - Production increased by re-employing existing, unused capacity and unemployed labour Peak- top of the cycle - Existing capacity used to a high degree - Possible labour shortages → key skills, essential raw materials - Costs begin to rise → business remains profitable - Peaks are eventually followed by slowdowns in economic activity - Sometimes slowing of the increase of income - Sometimes turns into r ecession (contraction) Recession- fall in real GDP for 2 successive quarters - Output falls → employment and household incomes fall - Profit falls → some firms encounter financial difficulties - Risky investments look unprofitable - Unused capacity increasing → may not be worth replacing equipment as it wears out - Depression - long and deep recession Slump- entire falling half of the business cycle Boom- entire rising half of the business cycle - Shows path of potential GDP since 1985 - Upward trend reflects productive capacity growth → caused by increases in the labour force, capital stock, level of technological knowledge Shows actual GDP - Kept approximately in step with potential GDP Distance between potential and actual GDP → output gap (ii) Downloaded by Ali Azim (azim7550@mylaurier.ca) lOMoARcPSD|9845003 - Fluctuations in output gap size → fluctuations in economic activity Why National Income Matters - Short-run movements in business cycle receive most attention in politics & press - Long-term growth = more important (reflected by growth of potential GDP) - Actual GDP below potential GDP - Recessions associated with unemployment and lost output → human suffering - Actual GDP above potential GDP - Inflationary pressure → concern for government (committed to keeping inflation low) *Inflation rate = - - CP 1 − CP 2 CP 2 * 100* Long-run trend in real p er capita national income - important determinant of improvements in a society’s overall standard of living - When income/person grows → each generation expects to be better off than the one before - Ex. Figure 19-1: per capita income grown at an average of 1.5%/year - Average person’s lifetime income = t wice of their grandparents Economic growth doesn’t affect everyone in the same way - Ex. Shifting away from agriculture & toward manufacturing - Might reduce some people’s material living standards for extended periods of time 19.2 - Growth vs. Fluctuations Long-Term Economic Growth - Both t otal output and o utput per person have risen for many decades (mostly industrial countries) - Rising average living standards - More important for a society’s living standards from decade to decade & generation to generation - Considerable debate of government policy’s ability to influence the economy’s long-run rate of growth - Some believe a policy designed to keep inflation low & stable → economy’s growth - Some believe there’s danger from having inflation too low → moderate inflation is more conducive to growth than a very low one - Many believe when governments spend less → rise in tax revenue → budget surplus → reduced need for borrowing → less interest rates → more investment by private sector - These increases imply higher stock of physical capital available for future production→ increase in economic growth - Chapter 31 - Growing debate about whether economic growth generates excessive costs (resource depletion & environmental damage) - Many think without appropriate policies, we can have continued growth without damaging the environment - Others argue long-term future is only sustainable with an intentional r eduction in the size of economy - Active debate with role of government in developing new technologies - Some believe that the private sector (on its own) can produce inventions & innovation that will guarantee a satisfactory rate of long-term growth - Others point out that almost all major new technologies in the past 75 years were initially supported by public funds (electronic computer was the creation of governments in WWII) Downloaded by Ali Azim (azim7550@mylaurier.ca) lOMoARcPSD|9845003 Chapter 20 - Measurement of National Income 20.1 - National Output and Value Added Double (multiple) counting- error in estimating a nation’s output by adding all sales of all firms Intermediate goods- all outputs used as inputs by other producers in a further stage of production Final goods- goods that aren’t used as inputs by other firms, but are produced to be sold Value Added- value of a firm’s output - value of the inputs that it purchases from other firms - Used by firms to avoid double counting - Sales revenue - Cost of intermediate goods - Payments owed to the firm’s factors of production - Correct measure of each firm’s contribution to total output - amount of market value produced by the firm and its workers - Net value of its output 20.2 - National Income Accounting: The Basics Value Added(value of domestic output) = value of the expenditure on output = total income claims generated by producing that output Downloaded by Ali Azim (azim7550@mylaurier.ca) lOMoARcPSD|9845003 Gross domestic product (GDP)- total value of goods and services produced in the economy during a given period GDP on the expenditure side- GDP calculated by adding up total expenditure for each of the main components of final output - Total expenditure on final output = sum of 4 categories of expenditure: - Consumption, investment, government purchases, net exports - Consumption Expenditure(C) - Expenditure on all goods and services for final use - Investment Expenditure(I) - E xpenditure on the production of goods not for present consumption - New plant & equipment (factories, computers, machines, warehouses) - Changes in Inventories - stocks of raw materials, goods in process, and finished goods held by firms to mitigate the effect of short-term fluctuations in production or sales - Decummulation - drawing down of inventories; disinvestment (negative investment) - Reduction in the stock of finished goods available to be sold - New Plant and Equipment - Capital Stock- aggregate quantity of capital goods - Fixed Investment- creation of new plant and equipment Downloaded by Ali Azim (azim7550@mylaurier.ca) lOMoARcPSD|9845003 New Residential housing - only appears as residential investment in national accounts when a new house is built - Gross & Net Investment - Depreciation- amount that capital stock is depleted through the production process - Net investment = Gross investment - Depreciation - Rare for net investments to be negative (economy’s capital stock is shrinking) - Total Investment - production of new investment goods is part of a nation's total current output, creating income → all gross investment is included in calculation of national income - Actual total investment expenditure (Ia) Government Purchases(G) - all government expenditure on currently produced goods and services, exclusive of government transfer payments - Cost vs. Market Value- government output valued at cost rather than at market value - Government Purchases vs. Government Expenditure- only government purchases of currently produced goods & services are included as a part of GDP - As a result, a great deal of government spending doesn’t count as part of GDP - Transfer payments - payments to an individual or institution not made in exchange for a good or service, therefore not a part of expenditure on a nation’s total output and not included in GDP Net Exports(NX) - value of total exports - value of total imports - Imports(IM) - value of all goods and services purchased from firms, households, or governments in other countries - Exports(X) - value of all domestically produced goods and services sold to firms, households, and governments in other countries Total Expenditure:GDP = Ca + Ia = Ga + (Xa - IMa) - - - - GDP on the income side- GDP calculated by adding up all the income claims generated by the act of production - Factor incomes- wages & salaries, interest, business profits, N et Domestic Income(sum of previous listed) - Non-Factor Payments- indirect taxes and subsidies, depreciation - Total National Income- factor incomes + depreciation + indirect taxes less subsidies 20.3 - National Income Accounting: Some Further Issues Nominal GDP-total GDP valued at current prices Real GDP- valued at base-period price - Total GDP valued at current prices is called nominal GDP GDP valued at base-period prices is called r eal GDP Downloaded by Ali Azim (azim7550@mylaurier.ca) lOMoARcPSD|9845003 GDP Deflator- an index number derived by dividing nominal GDP by real GDp, change measures the average change in price of all the items in the GDP GDP at current prices GDP - GDP deflator = GDP at base−period prices x 100 = N ominal Real GDP x 100 - Most comprehensive available index of price level because it includes all goods and services produced by the entire economy GDP Deflator vs. CPI - GDP deflator doesn’t necessarily change with changes in CPI - 2 price indices measure different things - Movements in C PI measures change in a verage price of consumer goods - Movements in G DP deflator measures change in average price of goods in Canada - Ex. Changes in world price of coffee would have a larger effect on CPI than the GDP deflator since Canadians drink a lot of coffee, but no coffee is produced here - Ex. Changes in world price of wheat would have an opposite effect since most of Canada’s considerable production of wheat is exported to other countries, leaving a relatively small fraction in the Canadian basket of consumer products - Changes in GDP deflator and CPI similarly reflect overall inflationary trends - Changes in relative prices, however, may lead to the 2 price indices to move in different ways Omissions from GDP- illegal activities, underground economy, home production, volunteering, leisure, economic “bads” Chapter 21 - The Simplest Short-Run Macro Model 21.1 - Desired Aggregate Expenditure - Use the same letters as Chapter 20 (C, I, G, & (X - IM)) without the subscript “a” to indicate desired expenditure in the same categories - Desired Aggregate Expenditure (AE)= C + I + G + (X - IM) - Desired expenditure doesn’t need to equal actual expenditure Downloaded by Ali Azim (azim7550@mylaurier.ca) lOMoARcPSD|9845003 - - Ex. firms might not plan to invest in inventory accumulation this year, but might do so unintentionally if sales are unexpectedly low - unsold goods pile up → undesired inventory accumulation → actual investment expenditure (Ia) exceeds desired investment expenditure (I) National income accounts measure a ctual expenditures in each of the 4 expenditure categories Autonomous vs. Induced Expenditure - Induced Expenditures - Any component of expenditure that is systematically related to national income - Autonomous Expenditures - elements of expenditure that don’t change systematically/depend with national income Important Simplifications - Closed Economy - an economy that has no foreigh trade in goods, services, or assets - There is no government (hence, no taxes), price level constant 21.2 - Equilibrium National Income Desired Consumption Expenditure - Disposable income (YD) - household income after tax - In our model, YD = Y - 2 types of disposable income: consumption & saving - Savings - all disposable income that’s not spent on consumption - Consumption function - the relationship between desired consumption expenditure and all the variables that determine it Downloaded by Ali Azim (azim7550@mylaurier.ca) lOMoARcPSD|9845003 - - - - Simplest case: it’s the relationship between desired consumption expenditure and disposable income - Key factors influencing desired consumption: disposable income, wealth, interest rates, expectations about the future Holding constant other determinants of desired consumption, an increase in disposable income is assumed to lead to an increase in desired consumption C = 30 + 0.8YD - Disposable income (YD) = 0 - Desired aggregate consumption = $30 billion - Autonomous consumption (> 0) - independent of the level of income - For every $1 increase in YD , desired consumption rises by $0.80 - Induced consumption - brought about by a change in income Consumption function (i) - intersection of 45° line, when income is $150 billion → break-even level of income Downloaded by Ali Azim (azim7550@mylaurier.ca) lOMoARcPSD|9845003 Average & Marginal Propensities to Consume Average propensity to consume (APC) - desired consumption divided by the level of disposable income - APC = C/YD Marginal propensity to consume (MPC) - change in desired consumption divided by the change in disposable income that brought it about - MP = ∆C/∆YD Slope of the Consumption Function - Consumption function has a slope of ∆C/∆YD (which is, be definition, MPC) The Saving Function - There are 2 saving concepts that are exactly parallel to the consumption concepts of APC and MPC - APC + APS = 1 - MPC + MPS = 1 - Average propensity to save (APS)- desired saving/disposable income = S/YD - Marginal propensity to save (MPS)- change in desired saving/change in disposable income that brought it about = ∆S/∆YD - Desired consumption > income = desired saving is negative (vice versa) Downloaded by Ali Azim (azim7550@mylaurier.ca) lOMoARcPSD|9845003 - An increase in household wealth shifts the consumption function up at any level of disposable income; a decrease in wealth shifts the consumption function down A Change in Interest Rates - Durable goods - goods that deliver benefits for several years (cars, household appliances) - Most are expensive → purchased on credit (households borrow in order to finance purchases) - Cost of borrowing = interest rate - Fall in interest rate → reduces cost of borrowing → increase in desired consumption expenditure (especially of durable goods) - Non-durable goods - consumption goods that deliver benefits to households for short periods of time (groceries, restaurant meals, clothing) Downloaded by Ali Azim (azim7550@mylaurier.ca) lOMoARcPSD|9845003 - - A fall in interest rates usually leads to an increase in desired aggregate consumption at any level of disposable income; the consumption function shifts up - A rise in interest rates shifts the consumption function down A Change in Expectations - Expectations about the future state of the economy often influences desired consumption - Optimism leads to an upward shift in the consumption function - Pessimism leads to a downward shift in the consumption function Summary 1. Desired consumption is assumed to be positively related to disposable income. In a graph, this relationship is shown by the positive slope of the consumption function, which is equal to the marginal propensity to consume (MPC). 2. There are both autonomous and induced components of desired consumption. A movement along the consumption function shows changes in consumption induced by changes in disposable income. A shift of the consumption function shows changes in autonomous consumption. 3. An increase in household wealth, a fall in interest rates, or greater optimism about the future are all assumed to lead to an increase in desired consumption and thus an upward shift of the consumption function. 4. All disposable income is either consumed or saved. Therefore, there is a saving function associated with the consumption function. Any event that causes the consumption function to shift must also cause the saving function to shift by an equal amount in the opposite direction. Desired Investment Expenditure - 3 categories of investment: inventory accumulation, residential construction, new plant and equipment Downloaded by Ali Azim (azim7550@mylaurier.ca) lOMoARcPSD|9845003 - Investment expenditure = most volatile component of GDP & changes in investment are strongly associated with aggregate economic fluctuations Consumption, government purchases, and net exports are much smoother over the business cycle, each typically changing by less than 1% point What explains fluctuations? Here we examine 3 important determinants of desired investment expenditure - Investment and the Real Interest Rate - Real interest rate represents the real opportunity cost of using money (either borrowed money or retained earnings) for investment purposes - Rise in real interest rate reduces amount of desired investment expenditure - Inventories - Changes in inventories represent only a small percentage of private investment in a typical year - Inventory investment is quite volatile → important influence on fluctuations in investment expenditure - When a firm ties up funds in inventories, those same funds cannot be used elsewhere to earn income. As an alternative to holding inventories, the firm could lend the money out at the going rate of interest. Hence, the higher the real rate of interest, the higher the opportunity cost of holding an inventory of a given size. Other things being equal, the higher the opportunity cost, the smaller the inventories that will be desired. Downloaded by Ali Azim (azim7550@mylaurier.ca) lOMoARcPSD|9845003 - - Residential Construction - Expenditure on newly built residential housing is also volatile. Most houses are purchased with money that is borrowed by means of mortgages. Interest on the borrowed money typically accounts for more than one-half of the purchaser’s annual mortgage payments; the remainder is repayment of the original loan, called the principal. Because interest payments are such a large part of mortgage payments, variations in interest rates exert a substantial effect on the demand for housing. - New Plant and Equipment - The real interest rate is also a major determinant of firms’ investment in factories, equipment, and a whole range of durable capital goods that are used for production. When interest rates are high, it is expensive for firms to borrow funds that can be used to build new plants or purchase new capital equipment. Similarly, firms with cash on hand can earn high returns on interest-earning assets, again making investment in new capital a less attractive alternative. Thus, high real interest rates lead to a reduction in desired investment in capital equipment, whereas low real interest rates increase desired investment. - The real interest rate also influences firms’ decisions to conduct expensive research activities to develop new products or processes. In Figure 21-4, firms’ investment in “intellectual property” products (the result of research activities) is included in the “plant and equipment” category and typically represents about one-sixth of that category or about 2 percent of GDP. - The real interest rate reflects the opportunity cost associated with investment, whether in inventories, residential construction, or new plant and equipment - The higher the real interest rate, the higher the opportunity cost & thus the lower the amount of desired investment Investment and Changes in Sales - Firms hold inventories to meet unexpected changes in sales and production, and they usually have a target level of inventories that depends on their normal level of sales. Because the size of inventories is related to the level of sales, the change in inventories (which is part of the current investment) is related to the change in the level of sales. - For example, suppose a firm wants to hold inventories equal to 10 percent of its monthly sales. If normal monthly sales are $100 000, it will want to hold inventories valued at $10 000. If monthly sales increase to $110 000 and persist at that level, it will want to increase its inventories to $11 000. Over the period during which its stock of inventories is being increased, there will be a total of $1000 of new inventory investment. - The higher the level of sales, the larger the desired stock of inventories - Changes in the rate of sales therefore cause temporary bouts of investment or disinvestment in inventories Downloaded by Ali Azim (azim7550@mylaurier.ca) lOMoARcPSD|9845003 - - - Changes in sales have similar effects on investment in plant and equipment. For example, if there is a general increase in consumers’ demand for products that is expected to persist and that cannot be met by existing capacity, investment in new plant and equipment will be needed. Once the new plants have been built and put into operation, however, the rate of new investment will fall. Investment and Business Confidence - When a firm invests today, it increases its future capacity to produce output. If it can sell the new output profitably, the investment will prove to be a good one. If the new output does not generate profits, the investment will have been a bad one. When it undertakes an investment, the firm does not know if it will turn out well or badly—it is betting on a favourable future that cannot be known with certainty. - When firms expect good times ahead, they will want to invest now so that they have a larger productive capacity in the future ready to satisfy the greater demand. When they expect bad times ahead, they will not invest because they expect no payoff from doing so. - Investment depends on firms’ expectations about the future state of the economy Investment as Autonomous Expenditure - We have seen that desired investment is influenced by many things, and a complete discussion of the determination of national income is not possible without including all of these factors. - For the moment, however, our goal is to build the simplest model of the macro economy in which we can examine the interaction of actual national income and desired aggregate expenditure. To build this simple model, we begin by treating desired investment as autonomous—that is, we assume it to be unaffected by changes in national income. Figure 21-5 shows the investment function as a horizontal line. Downloaded by Ali Azim (azim7550@mylaurier.ca) lOMoARcPSD|9845003 - We are making the assumption that desired investment is autonomous with respect to national income, not that it is constant. It is important that aggregate investment be able to change in our model since in reality investment is the most volatile of the components of aggregate expenditure. As we will soon see, shocks to firms’ investment behaviour that cause upward or downward shifts in the investment function are important explanations for fluctuations in national income. The assumption that desired investment is autonomous, and that the I function is therefore horizontal in F igure 21-5, is mainly for simplification. However, this assumption does reflect the fact that investment is an act undertaken by firms for future benefit, and thus the current level of GDP is unlikely to have a significant effect on desired investment. A “Demand-Determined” Equilibrium(assume firms are able and willing to produce any amount of output that’s demanded of them & that changes in production levels don’t require change in product prices) - Output is d emand determined (extreme assumption - normally when firms increase their output and move upward along individual supply curves, they would require a higher price for their product) - For any level of national income at which desired aggregate expenditure exceeds actual income, there will be pressure for actual national income to rise - Aggregate expenditure (AE) function- function that related desired aggregate expenditure to actual national income (no G or (X - IM) in this function) - AE = C + I Downloaded by Ali Azim (azim7550@mylaurier.ca) lOMoARcPSD|9845003 AE = $105 billion + (0.8) Y National income is in equilibrium when d esired aggregate expenditure = actual national income - For any level of national income at which desired aggregate expenditure > actual income, there will be pressure for actual national income to rise (vice versa) Marginal Propensity to Spend(z) - the change in desired aggregate expenditure on domestic output / change in national income that brought it about - ∆AE/∆Y → slope of aggregate expenditure function - 0<z<1 - The marginal propensity to spend is the amount of extra total expenditure induced when national income rises by $1, whereas the marginal propensity to consume is the amount of extra consumption induced when households’ disposable income rises by $1 Equilibrium: Desired AE = Actual Y Downloaded by Ali Azim (azim7550@mylaurier.ca) lOMoARcPSD|9845003 - - Desired aggregate expenditure > actual GDP → firms’ decisions to increase output will push up GDP (vice versa) These forces in the economy suggest a straightforward equilibrium condition - AE = Y The equilibrium level of national income occurs where desired aggregate expenditure = actual national income Brown line (AE = C + I) - aggregate expenditure function Black line (AE = Y) - equilibrium condition - Often referred to as the 45° line 21.3 - Changes in Equilibrium National Income Shifts of the AE Function - Shift in consumption function or investment function - Upward shifts in the AE function Downloaded by Ali Azim (azim7550@mylaurier.ca) lOMoARcPSD|9845003 Figure 21-8 shows that either kind of upward shift in the AE function increases equilibrium national income. After the shift in the AE curve, income is no longer in equilibrium at its original level because at that level desired aggregate expenditure exceeds actual national income. Given this excess demand, firms’ inventories are being depleted and firms respond by increasing production. Equilibrium national income rises to the higher level indicated by the intersection of the new AE curve with the 45° line. Downward shifts in the AE function - What happens to national income if there is a decrease in the amount of consumption or investment expenditure desired at each level of income? These changes shift the AE function downward, as shown in Figure 21-8 by the movement from the dashed AE curve to the solid AE curve. An equal reduction in desired expenditure at all levels of income shifts AE parallel to itself. A fall in the marginal propensity to spend out of national income reduces the slope of the AE function. In both cases, the equilibrium level of national income decreases; the new equilibrium is found at the intersection of the 45° line and the new AE curve. - - Downloaded by Ali Azim (azim7550@mylaurier.ca) lOMoARcPSD|9845003 - Changes in household wealth, such as those created by large and persistent swings in stock-market values, lead to changes in households’ desired consumption expenditure, thus changing the equilibrium level of national income. Summary - A rise in the amount of desired aggregate expenditure at each level of national income will shift the AE curve upward and increase equilibrium national income. - A fall in the amount of desired aggregate expenditure at each level of national income will shift the AE curve downward and reduce equilibrium national income. In addition, part (ii) of Figure 21-8 suggests a third general proposition regarding the effect of a change in the slope of the AE function: An increase in the marginal propensity to spend, z, steepens the AE curve and increases equilibrium national income. Conversely, a decrease in the marginal propensity to spend flattens the AE curve and decreases equilibrium national income. Chapter 22 - Adding Government and Trade to the Simple Macro Model 22.1 - Introducing Government A government’s fiscal policy (the use of the government’s tax and spending policies to achieve government objectives) is defined by its plans for taxes and spending. Government Purchases In Chapter 20, we distinguished between government purchases of goods and services and government transfer payments. The distinction bears repeating here. When the government hires a public servant, buys office supplies, purchases fuel for the Canadian Armed Forces, or commissions a study by consultants, it is adding directly to the demands for the economy’s current output of goods and services. Hence, desired government purchases, G, are part of aggregate desired expenditure. The other part of government spending, transfer payments, also affects desired aggregate expenditure but only indirectly. Consider welfare or employment-insurance benefits, for example. These government expenditures place no direct demand on the nation’s production of goods and services since they merely transfer funds to the recipients. The same is true of government transfers to firms, which often take the form of subsidies. However, when individuals or firms spend some of these payments on consumption or investment, their spending is part of aggregate expenditure. Thus, government transfer payments do affect aggregate expenditure but only through the effect these transfers have on households’ and firms’ spending. Downloaded by Ali Azim (azim7550@mylaurier.ca) lOMoARcPSD|9845003 In our macro model we make the simple assumption that the level of government purchases, G, is autonomous with respect to the level of national income. That is, we assume that G does not automatically change just because GDP changes. We then view any change in G as a result of a government policy decision. (The government’s transfer payments generally do change as GDP rises or falls, but it is G that is part of desired aggregate expenditure.) 22.2 - Introducing Foreign Trade Canada imports all kinds of goods and services, from French wine and Italian shoes to Swiss financial and American architectural services. Canada also exports a variety of goods and services, including timber, nickel, automobiles, engineering services, computer software, flight simulators, and commuter jets. U.S.–Canadian trade is the largest two-way flow of trade between any two countries in the world today. Of all the goods and services produced in Canada in a given year, roughly a third are exported. A similar value of goods and services is imported into Canada every year. To see how foreign trade is incorporated into our macro model, we need to see how exports (X) and imports (IM) affect desired aggregate expenditure (AE). Recall that AE is desired expenditures on domestically produced goods and services. Exports are purchases by foreigners of Canadian products and so are a component of A E. In contrast, imports are expenditures by Canadians on goods and services produced elsewhere and thus must be subtracted from total expenditures to determine AE. It is therefore net exports (X - IM) that appears in our macro model as part of AE. Net Exports Canada’s imports, however, depend on the spending decisions of Canadian households and firms. Almost all consumption goods have an import content. Canadian-made cars, for example, use large quantities of imported components in their manufacture. Canadian-made clothes most often use imported cotton or wool. And most restaurant meals contain some imported fruits, vegetables, or meats. Hence, as consumption rises, imports will also increase. Because consumption rises with national income, we also get a positive relationship between imports and national income (GDP). In our macro model, we use the following simple form for desired imports: IM=mY Where Y is GDP and m is the marginal propensity to import (m - the increase in import expenditures induced by a $1 increase in national income), the amount that desired imports rise when national income rises by $1. In our model, net exports can be described by the following equation: NX=X−mY Since exports are autonomous with respect to Y but imports are positively related to Y, we see that net exports are negatively related to national income. This negative relationship is called the net export function. Data for a hypothetical economy with autonomous exports and imports that are 10 percent Downloaded by Ali Azim (azim7550@mylaurier.ca) lOMoARcPSD|9845003 of national income (m = 0.1) are illustrated in Figure 22-1. In this example, exports form the autonomous component and imports form the induced component of desired net exports. Downloaded by Ali Azim (azim7550@mylaurier.ca) lOMoARcPSD|9845003 22.3 - Equilibrium National Income - Equilibrium is the level of income at which desired aggregate expenditure = actual national income - The addition of government and net exports changes the calculations that we must make but doesn’t alter the equilibrium concept or the basic workings of the model Adding Taxes to the Consumption Function - Recall: disposable income = national income - net taxes - YD = Y - T - We take several steps to determine the relationship between consumption and national income in the presence of taxes 1. Assume that net tax rate (t) is 10%, so that net tax revenues are 10% of national income (GDP): a. T = 0.1Y 2. Disposable income must therefore be 90% of national income Downloaded by Ali Azim (azim7550@mylaurier.ca) lOMoARcPSD|9845003 a. YD = Y - T = Y - 0.1Y = 0.9 Y 3. The consumption function we used last chapter is given as a. C = 30 + 0.8YD which tells us that the MPC out of disposable income is 0.8 4. We can not substitute 0.9Y for YD in the consumption function a. C = 30 + 0.8(0.9Y) C = 30 + 0.72Y So we can express desired consumption as a function of YD or as different function of Y. In this example, 0.72 = MPC*(1-t), where t is the net tax rate. Whereas 0.8 is the MPC out of disposable income, 0.72 is the MPC to consume out of national i ncome. - In the presence of taxes, the MPC out of national income < MPC to consume out of disposable income 22.4 - Changes in Equilibrium National Income - Changes in any of the components of desired aggregate expenditure will cause changes in equilibrium national income (GDP). In Chapter 21, we investigated the consequences of shifts in the consumption function and in the investment function. Here we take a first look at fiscal policy—the effects of changes in government spending and taxation. We also consider changes in desired exports and imports. First, we explain why the simple multiplier is reduced by the presence of taxes and imports. The Multiplier with Taxes and Imports In Chapter 21, we saw that the simple multiplier, the amount by which equilibrium real GDP changes when autonomous expenditure changes by $1, was equal to 1/(1-z), where z is the marginal propensity to spend out of national income. In the simple model of Chapter 21, with no government and no international trade, z was simply the marginal propensity to consume out of disposable income. But in the more complex model of this chapter, which contains both government and foreign trade, we have seen that the marginal propensity to spend out of national income is slightly more complicated. - The presence of imports and taxes reduces the marginal propensity to spend out of national income and therefore reduces the value of the simple multiplier. Let’s be more specific. In Chapter 21, the marginal propensity to spend, z, was just equal to the marginal propensity to consume. Let ΔY be the change in equilibrium national income brought about by a change in autonomous spending, Δ A. In this case, we have the following relationships: Downloaded by Ali Azim (azim7550@mylaurier.ca) lOMoARcPSD|9845003 - Without government and foreign trade: z = MPC 1 Simple multiplier = ΔY = 1−z ΔA = 1 - MPC In our example, MPC = 0.8, so the simple multiplier was 5: 1 1 - Simple multiplier = 1−0.8 = 0.2 =5 In our expanded model with government and foreign trade, the marginal propensity to spend out of national income must take into account the presence of net taxes and imports, both of which reduce the value of z. - With government and foreign trade: z = MPC(1-t) - m 1 Simple multiplier = ΔY = 1−z ΔA 1 = 1 − [M P C(1−t) − m] In our example, MPC = 0.8, t = 0.1, m = 0.1, making the simple multiplier = 2.63 1 - Simple multiplier = 1 − [0.8(1−0.1) − 0.1] = 1 1 − (0.72 − 0.1) 1 1 − 0.62 1 0.38 = = = 2.63 What is the central point? When we introduce government and foreign trade to our macro model, the simple multiplier becomes smaller. Since some of any increase in national income goes to taxes and imports, the induced increase in desired expenditure on domestically produced goods is reduced. (The AE curve is flatter.) The result is that, in response to any change in autonomous expenditure, the overall change in equilibrium GDP is smaller. - The higher the marginal propensity to import, the lower the simple multiplier. - The higher the net tax rate, the lower the simple multiplier 22.5 - Demand-Determined Output In this and the preceding chapter, we have discussed the determination of the four categories of aggregate expenditure and have seen how they simultaneously determine equilibrium national income in the short run. An algebraic exposition of the complete model is presented in the appendix to this chapter. Our macro model is based on three central concepts, and it is worth reviewing them. Equilibrium National Income Downloaded by Ali Azim (azim7550@mylaurier.ca) lOMoARcPSD|9845003 The equilibrium level of national income is the level at which desired aggregate expenditure equals actual national income (AE = Y). If actual national income exceeds desired expenditure, inventories are rising and so firms will eventually reduce production, causing national income to fall. If actual national income is less than desired expenditure, inventories will be falling and so firms will eventually increase production, causing national income to rise. The Simple Multiplier The simple multiplier measures the change in equilibrium national income that results from a change in the a utonomous part of desired aggregate expenditure. The simple multiplier is equal to 1/(1-z). Where z is the marginal propensity to spend out of national income. In the model of Chapter 21, in which there is no government and no foreign trade, z is simply the marginal propensity to consume out of disposable income. In our expanded model that contains both government and foreign trade, z is reduced by the presence of net taxes and imports. To review: - Simple multiplier = 1/(1-z) - Closed economy with no government: z = MPC - Open economy with government: z = MPC(1-t) - m Demand-Determined Output Our model is so far constructed for a given price level—that is, the price level is assumed to be constant. This assumption of a given price level is related to another assumption that we have been making. We have been assuming that firms are able and willing to produce any amount of output that is demanded without requiring any change in prices. When this is true, national income depends only on how much is demanded—that is, national income is demand determined. Things get more complicated if firms are either unable or unwilling to produce enough to meet all demands without requiring a change in prices. We deal with this possibility in Chapter 23 when we consider supply-side influences on national income. There are two situations in which we might expect national income to be demand determined. First, when there are unemployed resources and firms have excess capacity, firms will often be prepared to provide whatever is demanded from them at unchanged prices. In contrast, if the economy’s resources are fully employed and firms have no excess capacity, increases in output may be possible only with higher unit costs, and these cost increases may lead to price increases. The second situation occurs when firms are price setters. Readers who have studied some microeconomics will recognize this term. It means that the firm has the ability to influence the price of its product, either because it is large relative to the market or, more usually, because it sells a product that is differentiated to some extent from the products of its competitors. Firms that are price setters often respond to changes in demand by altering their production and sales, at least initially, rather than by adjusting their prices. Only after some time has passed, and the change in demand has persisted, do Downloaded by Ali Azim (azim7550@mylaurier.ca) lOMoARcPSD|9845003 such firms adjust their prices. This type of behaviour corresponds well to our short-run macro model in which changes in demand initially lead to changes in output (for a given price level). - Our simple model of national income determination assumes a constant price level. In this model, national income is demand determined. In the following chapters, we complicate the model by making the price level an endogenous variable. In other words, movements in the price level are explained within the model. We do this by considering the supply side of the economy—that is, those things that influence the costs at which firms can produce, such as technology and factor prices. When we consider the demand side and the supply side of the economy simultaneously, we will see that changes in desired aggregate expenditure usually cause both prices and real GDP to change. Downloaded by Ali Azim (azim7550@mylaurier.ca)