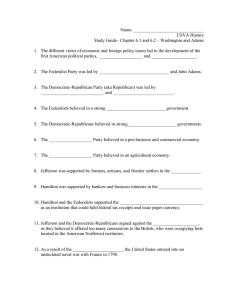

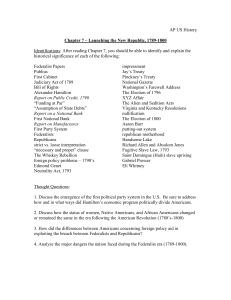

07 - Launching the New Republic 1789-1800

advertisement