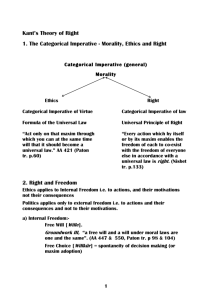

Amelia Westmoreland Dr. Thomas PHI 195 5 October 2019 Theory Essay 2: Deontology Another ethical theory that, like Utilitarianism, became articulated in the 18th century, is Deontology. Deontology states that we are “morally obligated to act in accordance with a certain set of principles and rules regardless of outcome” (Shakil, 2013). In essence, deontological ethics focuses on how we as human beings are duty bound to act. This does not in any way disregard our rights but does however give a clear path to follow in order that we are morally good. Deontology originally was addressed by utilitarianist Jeremy Bentham, who coined the term deontological. His description of deontology was a “knowledge of what is right or proper” (MacKinnon, 2018). This allowed it to be somewhat incorporated into his originally drafted theory of Utilitarianism. This description has since been developed by philosophers to directly contrast Utilitarianism. Contemporary philosophers emphasize deontology’s focus on duties and obligations, despite the consequences. A simple way of putting this is that deontology emphasizes the “right over the good” (MacKinnon, 2018). The benefits of actions are disregarded in favor of the morality of the motive/ the rightness of the action behind them. Many current philosophers believe that it is easiest to understand the core definition of deontology as it compares to consequentialism. In comparison to the theory of consequentialism, the category of which the previously discussed theory of Utilitarianism falls under, Deontology is a foil. Consequentialists believe that "choices are to be morally assessed solely by the state of affairs they bring about” (Stanford, 2016). Deontology, however, believes that the actions themselves are what should be held under judgement. Further, the motive behind those actions must be evaluated as a portion of what determines if that action is morally good. Every set of actions must follow certain moral rules, regardless of the situation. Consequentialism is universally easier to follow as an ethical theory because it allows more human opinion and decision to occur. Deontology is steadfast in its rules and does not regard the outcome as a term of measurement. Deontology branches out into two separate theories: the Categorical Imperative Theory and Divine Command Theory.Both of these theories are similar under the basic definition of deontology relating to duty but vary in the type of duties they adhere by. The Divine Command Theory falls under deontology under the justification that obeying God’s command is a form of duty and obligation. Essentially, something is right because a higher power deemed it right. This theory is present in many religions across the world. Each religion believes that their specified book written by God (i.e. the Bible or the Torah), or written through God’s voice (I.e. the Book of Mormon) contains the commands that God has given. For example, the ten commandments are strictly followed by the Christianity religion. However, the degree to which these are followed depends on the subtype of Christianity; Baptists are stricter in following certain ‘commands’ than Methodist are, so, hypothetically, they follow the Divine Command Theory better than Methodists. The Categorical Imperative Theory is most commonly associated with philosopher Immanuel Kant. Kant referred to the Categorical Imperative as the “supreme principle of morality” (Anscombe, 2001). Imperatives are a type of command, such as “drink your milk” or “clean the dishes.” There are two types of imperatives: hypothetical and categorical. A hypothetical imperative is an imperative that can be structured in an ‘if, then’ statement; an example would be “if you want to make good grades, then you must study.” For the hypothetical imperative, one thinks more of in a future tense. Categorical imperatives,however, are unconditional. If analyzing through the lens of a categorical imperative, one regards it more as if how they were using that imperative in the moment. These types of imperatives are irrefutable and are not specific or changed to suit any one situation. Categorical imperatives could include “don’t cheat” or “don’t kill.” Kant believes that morality should be based on the categorical imperative, as it would disable people from opting out of certain difficult rules or commands, simply because they wished to avoid the difficulty of living by that duty. Within the categorical imperative, there are two subtypes, called formulations. The first is the Formula of Universal Law (or the Formula of the Law of Nature). Under this formulation, one acts as if the maxim (rule) of your action were to become, through your will, a universal law of nature. Thus, everyone in the world would follow this maxim. Kant states that any maxim formulated through this lens must be able to “become a universal law without contradiction” (Shakil, 2013). This framework proves quite difficult to follow, because for every maxim that humans attempt to conform to the Universal Law, a situation can be found that might be the exception for that maxim. For example, many could claim that the maxim “don’t kill” should be accepted as a universal law. However, if one were to analyze the impacts of that maxim in reference to the debate of euthanization, it would be hard to justify keeping a person who wishes to die in the amount of pain they are in, in order that that universal law is followed. Truly, though it is supposed to be a literal formulation, it is better to regard this formulation as hypothetical. Kant doesn’t necessarily appear to need the world to adopt a universal maxim, but rather to just imagine what would happen if they did. You act as if you are living in a world following that universal maxim, even though it does not literally occur. The second formulation is the Formula of the End in Itself. This formula states that one should “Always treat humanity, whether in your own person or that of another, never simply as a means but always at the same time as an end” (MacKinnon, 2018). Kant believes that if we focus on treating each other as ends and not as means only, that that will affect who we are as human beings; being treated well will be elevating in a sense. This formulation is not difficult to put into literal action, rather than viewing it hypothetically as the Universal Law should be viewed. It is often used as a second step to evaluate an example created by the first form of the categorical imperative. Any one maxim should never, after evaluation, be found to be using a person as a means rather than an end. Overall, deontology is hypothetically easy to follow. However, there are many loopholes for deontology that makes it easy to ‘cheat the system’. These loopholes lie in how you formulate your maxim; the specificity of your maxim is determined by the human being, and we as human beings always find a way to put our own wellbeing into the maxims we formulate. For example, if your maxim is starts from the line of thought “I want to lie about something”, and then you picture a world where everyone lied, you would find that that world would not succeed. However, if you are more specific, such as “I should lie to protect an innocent refugee”, and imagine the world doing that, then the world looks more beneficial. Further, following deontology also means accepting that you will live by an ideal of how everyone should live but must understand that others around you might not. In reflection of the appliance of deontology to our Daybreak project, I have found it can be applied in terms of the motive (and duty) behind our project. At the beginning of this course, this project was, to me, simply a requirement for the class, that was a means to an end (the end being the grade). Though I do have a heart for service, truthfully, my duty was simply to my GPA, and I regarded the project in terms of a checklist. Now, however, my heart and obligation is to the people at Daybreak. Even though I have only been there twice briefly, I have found myself viewing the impact of this project as the end, rather than the project as a means to achieve a good grade. My motive and sense of duty has shifted, and thus, I am accurately abiding by the rules of the deontological theory. The maxim I follow is no longer following the hypothetical imperative of “if I do well on this project, then I will get a good grade.” Rather, it is following the categorical imperative “I should do this project for the people at Daybreak”, with the motive being that I wish to do good. This maxim, I believe, wouldwithstand both formulations of the categorical imperative. I believe, based on both the discussion within our class, and individual conversations that have been held, my team has also shifted their views of this project in analyzing this theory. We are no longer doing this project simply as a requirement, but because we believe it is morally good. I am eager to view our first visit to daybreak this coming Thursday through the lens of deontology, as I believe our project will conform to the framework of deontology more than it does the framework of utilitarianism. This ethical theory, while overall difficult to apply to every situation, is an accurate approach to this project, and I am anxious to see how our team uses it in the coming weeks. Works Cited Alexander, Larry, and Michael Moore. “Deontological Ethics.” Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, Stanford University, 17 Oct. 2016, https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/ethicsdeontological/#DeoFoiCon. Anscombe, Elizabeth. “Kantian Ethics.” CSUS, 2001, https://www.csus.edu/indiv/g/gaskilld/ethics/kantian ethics.htm. MacKinnon, Barbara, and Andrew Fiala. Ethics: Theory and Contemporary Issues. Cengage, 2018. Shakil, Ali. “Kantian Duty Based (Deontological) Ethics.” Seven Pillars, 29 Jan. 2013, https://sevenpillarsinstitute.org/kantian-duty-based-deontological-ethics/.