Anorectal Abscesses: Causes, Diagnosis, & Treatment

advertisement

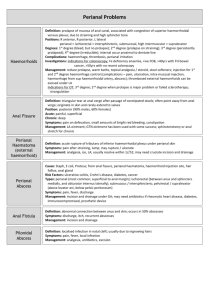

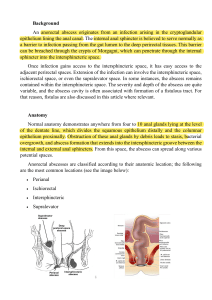

Anorectal abscesses are commonly caused by obstruction of the anal ducts, the ducts that drain the anal glands in the anal wall, helping to ease the passage of fecal matter through mucus secretion. My patient suffered from fluid stasis as a result of an obstruction of the anal duct, which could have caused his 18.2 WBC. Most pain patients have severe anal pain that can be connected to or unrelated to constipation, but is nonetheless constant. I have found this to be true for my patient since his pain intensity level ranges from 7 to 10. This is due to infection of the anal glands, which are not adequately draining through the anal crypts. The anal glands empty into ducts that traverse the internal sphincter and drain into the anal crypts at the level of the dentate line. Without adequate draining, infection of these glands can result in an abscess that can spread along multiple planes, such as the perianal, as in my patient's case, or the perirectal space. Around the anus, the perianal space connects with the fat of the buttock. After fluid collects, it can spread along the path of least resistance, which is commonly the intersphincteric space and other potential spaces, such as the supralevator or ischiorectal space. The organisms responsible for these abscesses include Clostridium species, Staphylococcus aureus, Streptococcus, and Escherichia coli. In most cases, a physical exam is all that is needed to diagnose. Patients with abdominal pain that does not seem to have an explanation or those with compromised immune systems who might not mount an immune response may benefit from computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging in the absence of the above symptoms and signs of infection. As was evident in my patient's case, laboratory testing usually reveals an elevated white blood cell count. In my patient's case, antibiotic therapy was initiated with Vancomycin and Zosyn. A proper analgesic should also be administered to the patient. Incision and drainage are the most common treatments for perianal abscesses. These can heal themselves with the secondary intention. In order to detect potential fistulasin-ano, protoscopy should be performed following drainage. The surgeon should consider inserting a seton if a fistula is identified; however, the tract should be clearly identifiable without unnecessary probing if a fistula is found. There is limited evidence to suggest that postoperative antibiotics following drainage of anorectal abscesses may lower the risk of fistula formation, a huge complication of perianal abscess. Other complications include Sepsis and recurrent abscesses. References: Banasik, J. L. (2018). Pathophysiology - E-book. Elsevier Health Sciences. Leeuwen, A. M., & Bladh, M. L. (2021). Davis's comprehensive manual of laboratory and diagnostic tests with nursing implications. F.A. Davis.