ICSA

CSQS: Corporate Governance

Course Notes

(1H /2019)

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Introduction to ICSA CSQS Corporate Governance .............................................................. iii

Corporate Governance Syllabus ............................................................................................ ix

SECTION 1: Concepts in Corporate Governance ................................................................. 1

Achievement Ladder Step 1 ............................................................................................... 28

SECTION 2: Governance: Principles v Rules ....................................................................... 29

SECTION 3: The Board of Directors ..................................................................................... 52

SECTION 4: Governance Practice ....................................................................................... 81

Achievement Ladder Step 2 ............................................................................................. 107

Section: Extra: Revision ...................................................................................................... 108

SECTION 5: Remuneration ................................................................................................ 114

SECTION 6: Reporting ....................................................................................................... 133

SECTION 7: Shareholders .................................................................................................. 171

Achievement Ladder Step 3 ............................................................................................. 190

SECTION 8: Internal Control .............................................................................................. 191

SECTION 9: Risk Management .......................................................................................... 209

SECTION 10: Corporate Social Responsibility ................................................................... 233

Achievement Ladder Step 4 ............................................................................................. 257

APPENDIX 1: Readings ...................................................................................................... 258

APPENDIX 2: Answers to Lecture Examples ..................................................................... 287

i

INTRODUCTION

ii

INTRODUCTION TO ICSA CSQS CORPORATE

GOVERNANCE

1 Resources

Important course dates

Syllabus & Course notes

Exam questions and quiz at the end of some sections

1st course mock exam

2nd course mock exam

Final mock exam is only revealed close to the final mock date.

2 The Course Notes

Please note that "This study material contains material copyright ICSA"

These course notes are designed to be used both in the classroom and outside the

classroom to help with your home study acting as a framework to add your own

notes.

They are not a precis of the ICSA study text, this is an integrated course of study,

which together with the study text, MyStudy recording, practice and revision kit, mock

exams and past exam papers forms a comprehensive assistance to learning,

understanding and then finally attempting the actual ICSA exam.

During each Section there are Lecture Examples, these have been designed to assist your

learning, please attempt them.

There are also a few areas to “complete” from the descriptions provided by your tutor during

the class, so please listen, ask questions and annotate the notes provided.

Some Sections have a Quick Quiz at the end, with answers provided. There are also some

longer answer questions. Don’t cheat and look at the answers before you try the questions!

Some of the questions in the Quick Quiz may require use of the text book to look up further

information.

It is vital that the major part of your learning is practising old exam questions. Just making

notes and reading is not enough to ensure a pass, question practice is essential.

•

Sections roughly follow the order of chapters in the study text, however the final

chapter in the study text (other!) is integrated into various different sections of the

notes.

•

Essentials that you must know

•

Quiz & questions for home study use

iii

•

Followed in class, with lecture examples throughout

•

A few home study sections

Answers to lecture examples in Appendix 2

Reading material in Appendix 1

ICSA suggest that you will need a minimum of 150 hours of study to successfully complete

and pass this course. You will need to develop effective study techniques, just reading the

notes or copying out the study text is not an effective technique. However there are effective

techniques and one of these is using your own mind maps.

Lecture example 1: Reading: Mind Maps

Please read the short article in appendix 1

3 The Study Text

The recommended text book:

Brian Coyle and Trina Hill

ICSA Study Text Corporate Governance

ICSA Publishing

As many students never get to the end of the study text book until it is too late! below is a list

of useful information that is in the appendices in the study text:

The appendices of the study text are very useful!!

Appendix 1: The UK Governance Code (replaced: please download the new 2018

version from FRC website)

Appendix 2: The G20 / OECD Principles

Appendix 3: FRC code and other guidance

Appendix 4: FRC guidance board effectiveness (replaced: please download the new

version from FRC website)

Appendix 5: FRC guidance on Audit Committees

iv

Appendix 6: FRC guidance on Risk Management, Internal Control and Related

Reporting (formally the Turnbulll Guidance)

Appendix 7: The UK Stewardship Code

Appendix 8: FRC Corporate Culture and The Role of Boards

Appendix 9: King Code IV

Glossary of terms

Directory of further reading

4 The exam

As with all ICSA CSQS exams the structure is as follows:

3 hours 15 minutes exam with a 50% pass mark

The first 15 minutes is reading time, you may write on the exam question paper only

There will be a choice of 6 questions, 4 must be attempted, each worth 25 marks.

All questions are long answer style, and may be divided into sub sections.

Each question will also have a small scenario associated with it.

5 Extra reading

It is important that you are reasonably up to date with new developments in Corporate

Governance as it is a constantly evolving subject. This is noted by the examiner in the

comments shown below. A useful website for guidance on corporate governance issues is

ICSAs own website

www.icsa.org.uk

ICSA publish a wide range of guidance notes on this subject, the study text does reproduce

some of the guidance in the text, but you should download some of the more important

guidance material for extra reading. The examiner often refers to specific ICSA guidance in

exam model answers.

6 Exam issues

Examiner comments

In answering the questions candidates need to show good analytical ability in discussing the

issues raised by the questions and how these issues applied to the case study.

Weaker answers are usually were either short of ideas or lacked common sense and

judgement.

v

Points that are made in an answer should be explained. It is not sufficient to make a

statement without justifying it or explaining your reasoning. Corporate governance should not

be a box-ticking exercise, but a large number of candidates write answers in a box-ticking

style, and fail to earn as many marks as they otherwise might do.

Bullet points?

A point that has been made in the past is that many candidates use brief lists of bullet points,

and their answers read like a hasty list of incomplete notes.

Comments from other exam reports on this topic have included

“Lists are acceptable as long as the answers present the points sufficiently clearly and

completely for the marker to understand the point. If candidates make „bullet points‟ that fail

to explain sufficiently the point they are trying to make, and leave it to the reader to „fill in the

gaps‟, they will not get credit and will not earn marks.”

Candidates who may think they „got the answer right‟ might well have earned inadequate

marks by failing to make their points sufficiently full and clear.

Structure answers

There is considerable time pressure on candidates in the exam. Even so, some candidates

might have scored higher marks if they had taken a short time to think about how to answer

a question and to plan the points they could make. Without some answer planning, there

may be a tendency to become repetitive, or to present rambling answers that lack structure.

Some additional comments from a previous examiner of this paper that echo the ones

above:

Stay on track

Take time to read the question carefully and to plan your answer to address the points

raised, not just cover the topic generally – or, worse still, waffle at length and at random.

Good candidates, and all those achieving merit or distinction, showed ability to analyse

problems and to set out the issues involved in a particular topic clearly, often giving points

both in favour and against the proposition. The better candidates showed awareness of

current debates in corporate governance, especially in their own country.

Very basic exam technique makes marking less stressful!

7 Model answers

Due to the nature of this subject there are often various “right” answers to a question,

therefore the answers suggested may be slightly different to the answer you have written,

that does not mean your answer is incorrect.

vi

The length of the suggested answers is also often somewhat exaggerated from what might

be achieved in the reality of an unseen three hour examination. Each answer explores

several areas that might be covered, but is intended as an indication of what is required

rather than as a definitive “right” answer.

At this level, candidates are expected to reason and to apply their varied experience to date

to the issues raised. Please do not be discouraged. Shorter answers, with less narrative but

clear evidence of knowledge, understanding and analytical ability, are well rewarded if

relevant points are covered adequately and the question set is addressed.

Course mock exams

Course mock exams general information

Please start each question on a new sheet of paper, write on both sides of the paper in blue

or black ink only, however if you are going to scan your answers then it may be better to

write on one side as it will be a clearer scan.

Complete all the detail on the front sheet, i.e. Name, return address, then detach it and

attach it to your answers,(you keep the questions), then send to BPP.

Typed answers, unless with prior permission, are NOT acceptable.

Return completed exams by due date, you can scan & covert to pdf and then email, but this

must be legible, if it is not it may not get marked.

Email address: Jerseyenquiries@bpp.com

Postal address:

ICSA Administration, BPP Professional, Whiteley Chambers, 39, Don Street St Helier,

Jersey, Channel Islands, JE2 4TR

Course exam 1

The exam is 1 hour and 40 minutes (1 hour 30 minutes writing, 10 minutes reading time)

There are two compulsory questions

You can use your notes / study text

Course exam 2

The exam is 2 hours and 30 minutes including 15 minutes reading time

There are three compulsory questions

You can use your notes / study text

vii

Final Mock exam

The exam is 3 hours 15 minutes with 15 minutes reading time at the start of the exam and

then 3 hours writing. You may write on the exam paper only in the reading time.

Candidates should attempt FOUR QUESTIONS ONLY from the choice of six, all of which

carry 25 marks each.

The exam should be completed under exam conditions, for “Face to Face” students this will

be at BPP offices.

NO BOOKS or NOTES should be used

viii

CORPORATE GOVERNANCE SYLLABUS

Module outline and aims

The aim of the Corporate Governance module is to equip the Chartered Secretary with the

knowledge and key skills necessary to act as adviser to governing authorities across the

private, public and voluntary sectors. The advice of the Chartered Secretary will include all

aspects of the governance obligations of organisations, covering not only legal duties, but

also applicable and recommended standards of best practice.

The module will enable the development of a sound understanding of corporate governance

law and practice in a national and international context. It will also enable you to support the

development of good governance and stakeholder dialogue throughout the organisation,

irrespective of sector, being aware of legal obligations and best practice.

Learning outcomes

On successful completion of this module, you will be able to:

Appraise the frameworks underlying governance law and practice in a national and

international context.

Advise on governance issues across all sectors, ensuring that the pursuit of strategic

objectives is in line with regulatory developments and developments in best practice.

Analyse and evaluate situations in which governance problems arise and provide

recommendations for solutions.

Demonstrate how general concepts of governance apply in a given situation or given

circumstances.

From the perspective of a Chartered Secretary, provide authoritative and professional

advice on matters of corporate governance.

Assess the relationship between governance and performance within organisations.

Apply the principles of risk management and appraise the significance of risk

management for good governance.

ix

Compare the responsibilities of organisations to different stakeholder groups, and

advise on issues of ethical conduct and the application of principles of sustainability

and corporate responsibility.

Syllabus content

Candidates will be required to discuss in detail statutory rules and the principles or

provisions of governance codes, and apply them to specific situations or case studies.

Candidates will also be expected to understand the role of the company secretary in

providing support and advice regarding the application of best governance practice.

Although the syllabus presents governance issues mainly from the perspective of

companies, candidates may be required to apply similar principles to non-corporate entities,

such as those in the public and voluntary sectors.

Governance is a continually developing subject, and good candidates will be aware of any

major developments that have occurred at the time they take their examination.

The detailed syllabus set out here has a strong UK emphasis, and it is expected that UK

corporate governance will be the focus of study for most candidates. A good knowledge of

the principles and provisions of the UK Corporate Governance Code will therefore be

required, together with any supporting Guidance on the Code published from time to time by

the Financial Reporting Council. However, a good knowledge and understanding of the code

of corporate governance in another country will be acceptable in answers, provided that

candidates indicate which code they are referring to in their answer.

The UK Corporate Governance Code (‘the Code’; formerly ‘the UK Combined Code’) is

subject to frequent review and amendment by the Financial Reporting Council. You are

advised to check the student newsletter and student news area of the ICSA website to find

out when revisions to the Code will first be examined.

Candidates will not be required to learn in detail codes of governance in countries other than

the UK, although they will be given credit for referring to the code in their own country

outside the UK. Similarly they will not be required to learn in detail codes of governance for

unquoted companies, public sector bodies or not-for-profit organisations. However they must

be prepared to discuss governance issues in these organisations, and be aware of how

these issues differ from corporate governance in listed companies.

x

General principles of corporate governance – weighting 10%

The nature of corporate governance and purpose of good corporate governance

Separation of ownership and control

Agency theory and corporate governance

Stakeholder theory and corporate governance

Key issues in corporate governance

Leadership and effectiveness of the board; accountability; risk management and

internal control; remuneration of directors and senior executives; relations with

shareholders and other stakeholders; sustainability

Principles of good corporate governance

OECD Principles of Corporate Governance

Framework of corporate governance

Legal framework

Rules-based and principles-based approaches

Codes of corporate governance and their application: UK Corporate Governance

Code

Concept of ‘comply or explain’

Governance and ethics

Potential consequences of poor corporate governance

The board of directors and leadership – weighting 10%

Role of the board

Division of responsibilities on the board

Matters reserved for the board

Role and responsibilities of the board chairman

Role and responsibilities of the Chief Executive Officer

xi

Role and responsibilities of non-executive directors

Independence and non-executive directors

Role of the Senior Independent Director

Statutory duties of directors

Rules on dealing in shares by directors: insider dealing; Model Code

Liability of directors: directors’ and officers’ liability insurance

Unitary and two-tier boards

Effectiveness of the board of directors – weighting 15%

Role of the company secretary in governance

Size, structure and composition of the board: board balance

Board committees

Appointments to the board: role of the Nomination Committee; succession and board

refreshment

Induction and development of directors

xii

Information and support for board members

Performance evaluation of the board, its committees and individual directors

Re-election of board members

Governance and accountability – weighting 10%

Financial and business reporting and corporate governance

The need for accountability and transparency

The need for reliable financial reporting: true and fair view, going concern statement

Responsibility for the financial statements and discovery of fraud

Role of the external auditors

Auditor independence; threats to auditor independence; auditors and non-audit work

The Audit Committee: roles, responsibilities, composition; FRC Guidance

Reporting on non-financial issues: narrative reporting; strategic report

Remuneration of directors and senior executives – weighting 10%

Principles of remuneration structure: elements of remuneration

xiii

Remuneration policy

Elements of a remuneration package and the design of performance-related remuneration

Candidates will not be required to discuss performance targets in detail, but need to be

aware of short-term incentives (e.g. cash bonuses) and longer term bonuses (share

grants, share options).

Difficulties in designing a suitable remuneration structure

Role of the Remuneration Committee

Compensation for loss of office

Disclosures of directors’ remuneration

Candidates will be expected to show an awareness of issues relating to the disclosure

of directors’ remuneration in the annual report and accounts, but not the detail (e.g. not

the detail of the directors’ remuneration report)

Shareholder approval of incentive schemes and voting rights with regard to remuneration

The recommendations or guidelines of institutional investor groups on matters relating to

directors’ remuneration

Relations with shareholders – weighting 10%

The equitable treatment of shareholders; protection for minority shareholders

Rights and powers of shareholders

Dialogue and communications with institutional shareholders (companies) or major

stakeholders

Role of institutional investor organisations (or major stakeholders)

xiv

In the UK, the role of the ABI and PLSA and the relevance for corporate governance

UK Stewardship Code

Constructive use of the annual general meeting

Shareholder activism

Candidates will be required to have an awareness of the benefits of electronic

communications between companies and their shareholders, but will not be required to know

the detailed law and regulations on electronic communications.

Risk management and internal control – weighting 15%

The nature of risks facing companies and other organisations: categories of risk

The difference between ‘business risk’ and ‘governance risk’ (internal control risk)

Internal control risks: financial, operational and compliance risks

Elements in an internal control system: FRC guidance

Risk and return; identifying, monitoring and reporting key risk areas; risk appetite and risk

tolerance; responsibility of the board of directors

Responsibilities for risk management and internal control: board of directors, executive

management, audit committee, internal and external auditors

Risk Committees of the board

Risk management committees

Role of internal audit within an internal control system

Disaster recovery plans

Whistle-blowing policy and procedures

ICSA best practice on whistle-blowing procedures

Reviewing and reporting on the effectiveness of the risk management and internal control

systems

xv

Corporate social responsibility and sustainability – weighting 10%

The nature of sustainability

The nature of corporate responsibility and corporate citizenship

Corporate responsibility and stakeholders

Internal and external stakeholders

Elements of corporate social responsibility: employees, the environment, human rights,

communities and social welfare, social investment, ethical conduct

Reputation risk: placing a value on reputation

Formulating and implementing a policy for corporate social responsibility

Reporting to stakeholders on sustainability and corporate social responsibility issues

Voluntary social and environmental reporting

Sustainability reporting: triple bottom line; GRI Guidelines

Integrated reporting

Other governance issues– weighting 10%

International aspects of corporate governance

Governance problems for large global groups of companies

Corporate governance: unquoted companies and small quoted companies

xvi

Governance in the public sector

Governance in the not-for-profit sector

End of introduction

xvii

COURSE NOTES

xviii

SECTION 1: Concepts in Corporate Governance

SECTION 1: CONCEPTS IN CORPORATE

GOVERNANCE

Lecture Example 1a: Class Exercise/Discussion: Corporate Governance?

Required

Brainstorm the following: What is Corporate Governance?

You may want to think about the origins of governance including scandals, risk, reputation,

regulation, principles, and ethics.

What Is

Corporate

Governance?

Governance?

1

SECTION 1: Concepts in Corporate Governance

1 Introduction

The subject of corporate governance leapt into the global news limelight from obscurity after

a string of collapses and scandals involving high profile companies. In the early 90’s in the

UK these were companies such as the Mirror Group and Barings Bank.

Some leading figures recognised the rising importance of corporate governance:

“The proper governance of companies will become as crucial to the world economy as the

proper governing of countries”

James Wolfensohn – Former President of the World Bank

The Economist 2nd January 1999

Then later in the USA, Enron, the Texas based energy giant, and WorldCom, so dominant in

the U.S. telecom industry, shocked the business world with both the scale and age of their

unethical and illegal operations.

The subject has stayed firmly on the front pages with the financial difficulties in 2007 of

Lehman Brothers with the resulting world-wide repercussions. More recently the problems at

News International and other newspapers show that it is not just financial considerations that

are part of the subject, business ethics being also an important element.

2 The Enron Issues

The Enron scandal illustrates some of the poor governance issues that will be dealt with in

more detail in the course:

1. Misleading transactions in accounts with approval of executives

2. Audit committee approved fraudulent accounts

3. Auditors and others employed by Enron profited from transactions with Enron.

4. Totally ineffective board, lots of non-executives, but most not independent and

dominated by executives

5. Board ignored whistleblowers

6. Inappropriate remuneration and rewards for directors

7. Unethical business practices

2

SECTION 1: Concepts in Corporate Governance

Lecture example 1b: reading: Scandals

Please read the articles in appendix 1

The subject has become part of everyday language, so much so that it now features in Pub

Quizzes…………….

Lecture example 2: Class Exercise / Discussion: Pub Quiz

The Pub Quiz

1) Which executive chairman disappeared off his boat in 1991?

2) Which company, listed on AIM (the alternative investment market) had an issue with

fraud concerning its accounts in 2018?

3) What job did Sir Adrian Cadbury of the Cadbury report have at Cadbury Schweppes

and Sir Richard Greenbury of the Greenbury report have at M&S?

4) What is a golden parachute?

5) What is retirement by rotation?

3

SECTION 1: Concepts in Corporate Governance

3 Definitions of corporate governance

“Governance” refers to the way “something” is governed. This could include a vast range of

“something’s” from a country to a local council, a charity, a school to a Parish Church.

Therefore the concepts of Governance cover a vast range of organisations from those firmly

in the profit making sector to those in the not for profit areas and public service domains.

General definition

A more general definition by Sir Adrian Cadbury, Chairman of the Cadbury Committee, 1992

which features some of the principles of corporate governance:

“Corporate Governance, the system by which organisations are directed and controlled, is

based on concepts of transparency, independence, accountability and integrity”

Local Government

The Chartered Institute of Public Finance and Accountancy (CIPFA) adapted the Cadbury

definition for the local government sector. It defines corporate governance as

“the systems and processes, the cultures and values, by which local government bodies are

directed and controlled and through which they account to, engage with and, where

appropriate, lead their communities”.

Governance of companies

The governance of companies tends to dominate the subject so a definition with regards to

this area is below

Corporate governance can be defined as:

A set of relationships between a company’s directors, its shareholders and other

stakeholders. It also provides structure through which the objectives of the company

are set, and the means of obtaining these objectives and monitoring performance are

determined.

At a basic level, governance is a fundamental internal control system, consisting of the

culture of the company and the policies and procedures operating within that culture,

ensuring the best interests of the company are serviced in the most effective manner.

Lecture example 3: Class Exercise (exam standard): Benefits & Drawbacks

Required

Assess the benefits and drawbacks to a business of applying a framework for corporate

governance.

4

SECTION 1: Concepts in Corporate Governance

Solution

Benefits

Drawbacks

For corporate governance to be effective it must be a feature of the inherent business

culture, i.e. the way business is conducted. However the challenge is to find a way in which

the interests of shareholders, directors and other stakeholders can be sufficiently satisfied.

4 Stakeholders in corporate governance

A definition

Stakeholders are people, groups or organisations that can affect or be affected by the

actions or policies of an organisation. Each stakeholder group has different expectations

about what it wants, and therefore different claims upon the organisation.

5

SECTION 1: Concepts in Corporate Governance

5 Classifying Stakeholders

Stakeholders can be classified in various ways,

Proximity

The method shown below is based on proximity to the organisation

Financial

Another method of grouping stakeholders is based on their financial interest in the

organisation.

Financial stakeholders with a direct financial stake in the organisation would be shareholders

and providers of loan capital such as banks and bond holders. All other stakeholders would

be classified as non-financial.

Shareholders: sub divisions

Institutional shareholders can be long term or short term investors. Short term investors such

as hedge funds are mainly looking for short term profit. There are various organisations that

act in the interests of the investment market.

The Association of British Insurers (ABI)

The Pension and Lifetime Savings Association (PLSA) (formerly The National Association of

Pension Funds (NAPF))

Pensions Investment Research Consultants Limited PIRC (www.PIRC.co.uk) an

independent investors advisory body and pressure group

A worldwide organisation:

The International Corporate Governance Network (ICGN)

6 How powerful are stakeholder groups?

A useful mapping tool for the analysis of stakeholder power and interest in an organisation is

the Mendelow matrix.

6

SECTION 1: Concepts in Corporate Governance

Mendelow classifies stakeholders on a matrix [below] whose axes are power held and

likelihood of showing an interest in the organisation’s activities. These factors will help define

the type of relationship the organisation should seek with its stakeholders, and how it should

view their concerns.

Stakeholder theory proposes corporate accountability to a broad range of stakeholders. It is

based on companies being so large, and their impact on society being so significant that

they cannot just be responsible to their shareholders. Stakeholders should be seen not as

just existing, but as making legitimate demands upon an organisation. The relationship

should be seen as a two-way relationship FORWARD

What stakeholders want from an organisation will vary. Some will actively seek to influence

what the organisation does and others may be concerned with limiting the effects of the

organisation's activities upon themselves.

There is considerable dispute about whose interests should be taken into account. The

legitimacy of each stakeholder's claim will depend on your ethical and political perspective

on whether certain groups should be considered as stakeholders.

The OECDs (The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development) principles of

corporate governance specifically recognises the rights and roles of stakeholders.

Provision 5 of the UK Corporate Governance Code 2018 now makes it a requirement for

boards to understand the views of stakeholders, in particular employees. It states

The board should understand the views of the company’s other key stakeholders and

describe in the annual report how their interests and the matters set out in section 172 of the

Companies Act 2006 have been considered in board discussions and decision-making.

The board should keep engagement mechanisms under review so that they remain effective.

For engagement with the workforce, one or a combination of the following methods should

be used:

7

SECTION 1: Concepts in Corporate Governance

• a director appointed from the workforce;

• a formal workforce advisory panel;

• a designated non-executive director.

If the board has not chosen one or more of these methods, it should explain what alternative

arrangements are in place and why it considers that they are effective.

Lecture example 4: Exam standard question: Stakeholders

Corporate governance reports worldwide have concentrated significantly on the roles,

interests and claims of the internal and external stakeholders involved in a publically listed

company.

Required

List some of these stakeholders and their claims on the organisation

Solution

8

SECTION 1: Concepts in Corporate Governance

7 Instrumental and normative views of stakeholders

Donaldson and Preston suggested that there are two motivations for organisations

responding to stakeholder concerns.

8 Instrumental view of stakeholders

This reflects the view that organisations have mainly economic responsibilities (plus the legal

responsibilities that they have to fulfil in order to keep trading). In this viewpoint fulfilment of

responsibilities towards stakeholders is desirable because it contributes to companies

maximising their profits, or fulfilling other objectives such as gaining market share or meeting

legal or stock exchange requirements. Therefore a business does not have any moral

standpoint of its own. It merely reflects whatever the concerns are of the stakeholders it

cannot afford to upset, such as customers looking for green companies or talented

employees looking for pleasant working environments. The organisation is using

shareholders instrumentally to pursue other objectives.

9 Normative view of stakeholders

This is based on the idea that organisations have moral duties towards stakeholders in

addition to the economic ones. Thus accommodating stakeholder concerns is an end in

itself. This suggests the existence of ethical and philanthropic responsibilities as well as

economic and legal responsibilities.

10 Theoretical frameworks of Governance

We have already dealt with stakeholder theory as a frame work of corporate governance;

however there are two other frameworks that should be considered

11 Agency Theory (Jensen and Mekling)

Agency theory is used to study the problems of motivation and control when a principal

needs the help of an agent to carry out activities. Agency theory would describe the

shareholders in a company as the principals, with the board their agents who are

empowered to act in their interests.

9

SECTION 1: Concepts in Corporate Governance

In practice the powers of shareholders tend to be very restricted. They normally have no

right to inspect the books of account, and forecasts of future prospects are gleaned from the

annual report and accounts, stockbrokers’ reports and media sources.

There is an information asymmetry; the agent has more information than the principal.

The diagram below illustrates how agency works in practice:

Agency theory assumes that agent and principal act in their own self-interest. These

interests may conflict. The separation of ownership from management can cause issues if

there is a breach of trust by directors either by intentional action, omission, neglect, or

incompetence.

Lecture example 5 Class discussion: Shareholder concerns

Required

Briefly suggest some reasons why shareholders might become concerned about the

management of an organisation in which they hold an investment.

Solution

10

SECTION 1: Concepts in Corporate Governance

12 The agency solution

One power that shareholders possess is the right to remove the directors from office. But

shareholders have to take the initiative to do this, and in many companies, the shareholders

lack the energy and organisation to take such a step. Ultimately they can vote in favour of a

takeover or removal of individual directors or entire boards, but this may be undesirable.

Shareholders can take steps to exercise control, but such action will be expensive, time

consuming and difficult to manage because it is difficult to:

(a) Verify what the board is doing, partly because the board has access to more information

about its activities than the principal does; and

(b) Introduce mechanisms to control the activities of the board, without preventing it from

functioning effectively.

Any steps taken by shareholders are likely to incur agency costs.

Lecture example 6 Exam question: Controlling the board

Required

Suggest some ways in which shareholders can monitor and control a board of directors.

(and likely to incur agency costs in doing so)

Solution

Monitoring systems

11

SECTION 1: Concepts in Corporate Governance

Controls

13 Exam practice question analysis

Briefly explain agency theory, and how it relates to corporate governance. (5 marks)

Question analysis:

The question is in 2 parts: Briefly explaining (making clear) a theory and then explaining how

it is connected to governance.

Should be answered in two sections, so two distinct paragraphs.

Marking scheme: 3 marks can be awarded for each section, but maximum 5 marks for the

question.

Time: 5 marks x 1.8 minutes a mark = 9 minutes max

Typical Answer

Agency theory (as applied to companies) was developed by Jensen and Meckling. The

theory is based on the concept of the separation of ownership of companies (equity

shareholders) from control (executive management or the board of directors). With the

managers/directors being the agents of the principals, the shareholders.

In the context of corporate governance, agency theory defines the relationship between

directors and the shareholders. It clearly illustrates that both expressed and implied authority

is given to the board to deal with any third party. Such actions should always be conducted

in the manner of promoting the success of the company in best interests of the shareholders.

14 Approaches to Corporate Governance

There has been considerable debate about what the objectives of sound Corporate

Governance should be. The different views can be divided into 3 broad approaches:

a)

Shareholder value approach

Traditional approach

12

SECTION 1: Concepts in Corporate Governance

b)

Directors should run companies with the maximisation of shareholder wealth as their

principle focus

Shareholders should have the power to remove directors if this isn’t achieved

In pursuit of wealth maximisation, directors will act fairly in the interests of other

stakeholders.

Stakeholder approach (pluralist approach)

c)

Public policy perspective: directors should be permitted or required to balance the

interests of shareholders and stakeholders.

The balance social and economic goals

Problem: company law biased towards shareholder rights. However there are many

other aspects of law protecting the rights a various stakeholders groups

Enlightened shareholder approach

Directors should pursue the interests of their shareholders, but in an enlightened and

inclusive way.

Look L/T not S/T

Create and maintain dialogue with other stakeholder groups

Shareholders as ‘enlightened’ investors?

Institutional investors will need to listen more to their beneficiaries

15 The King Reports

The South African King Reports (King 2, 2004, King 3, 2009 & King IV 2015) reject the

enlightened shareholder approach in favour of the stakeholder approach, stating that the

shareholders do not have predetermined position above the other stakeholder groups.

The King Report defined the following two terms:

Accountability:

the liability to render account to someone else.

Responsibility:

the liability of a person to be called to account when he is responsible.

Main points:

Directors should only be accountable to shareholders

Accountable to too many groups would restrict enterprise and flair.

Directors should be responsible to other stakeholders.

13

SECTION 1: Concepts in Corporate Governance

16 Principles of good corporate governance

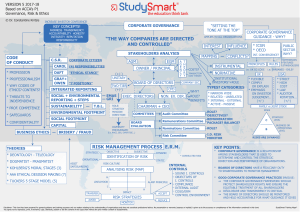

The following diagram illustrates the 9 core principles that underlie good corporate governance

16 Brief definitions of these principles

Integrity: Straightforward dealing and completeness; high moral character; honesty.

Fairness: Respecting the rights and views of any group with a legitimate interest.

Judgement: Making decisions that enhance the organisation’s prosperity.

Independence: Having only limited or strictly controlled links to the organisation.

Openness: Disclosure, including voluntary disclosure of reliable information.

Probity: Truthful and not misleading.

Responsibility: Systematic correction of errors, failures or mismanagement.

Accountability: Answerable for the consequences of actions.

Reputation: Stakeholders perception or expectations. A valuable asset of the

organisation.

17 Ethics and governance

Ethics is concerned with right and wrong and how conduct should be judged to be good or

bad. It is about how we should live our lives and, in particular, how we should behave

towards other people. It is therefore relevant to all forms of human activity.

Business life is a fruitful source of ethical dilemmas because its whole purpose is material

gain, the making of profit. Success in business requires a constant, avid search for potential

14

SECTION 1: Concepts in Corporate Governance

advantage over others and in business, people are under pressure to do whatever yields

such advantage.

It is important to understand that if ethics is applicable to corporate behaviour at all, it must

therefore be a fundamental aspect of mission, since everything the organisation does flows

from that. Managers responsible for strategic decision making cannot avoid responsibility for

their organisation's ethical standing. They should consciously apply ethical rules to all of

their decisions in order to filter out potentially undesirable developments. The question is

however what ethical rules should be obeyed. Those that always apply or those that hold

only in certain circumstances?

Ethical assumptions underpin all business activity as well as guiding behaviour. The

continued existence of capitalism makes certain assumptions about the 'good life' and the

desirability of private gain, for example.

Managing stakeholders: Corporate ethical codes

Organisations have responded to wide and varied pressures from external stakeholders to

be seen to act ethically by publishing ethical codes, actually a requirement of Sarbanes

Oxley in the USA

Ethical codes contain a series of statements setting out the organisation's core values and

explaining how it sees its responsibilities towards its stakeholders. They cover specific areas

such as gifts, anti-competitive behaviour and so on.

The typical features of an ethical code could be as follows:

Guidance on acceptable and unacceptable behaviour

Specific examples of company expectations

Links to the organisation's mission and objectives

Clear guidance on consequences and sanctions

Standards for the ethical treatment of suppliers, customers, employees

A corporate code of ethics has no value unless it has the full support of the board of

directors and senior management.

To reinforce this, the company secretary should ensure the board reviews the code of ethics

regularly and that it is issued annually to all employees to remind them of its requirements. It

might also be appropriate for the managers to sign up to the code annually to confirm their

observance and that it is being followed in their areas.

If it is fully supported by the board and senior management, a code of ethics has several

potential benefits to a company:

(i) It establishes policies for conduct and behaviour within an organisation that all employees

know they are expected to observe. A code should set out clearly what forms of behaviour

are, or are not, required.

15

SECTION 1: Concepts in Corporate Governance

(ii) It helps to ensure compliance with laws and regulations: this is important because noncompliance could result in legal action against the company, resulting possibly in additional

costs and loss of reputation

(iii) A code of ethics should also ensure that a high quality of service is provided to external

stakeholders, particularly suppliers and customers. This should help to improve the

company’s dealings with them and may, in the longer term, give it a strong reputation and

help to attract customers. In addition, if suppliers are made aware the existence of the code

of ethics, they should be discouraged from attempting unethical/illegal behaviour.

(iv) Following a code of ethical behaviour should also help manage stakeholder relations

with employees and shareholders. Ethical conduct by management in their dealings with

employees and employee representatives may help to improve industrial relations within the

company. Ethical conduct in relations with shareholders, including openness and

transparency, should help to reinforce the accountability of the board to its shareholders, and

so improve the quality of corporate governance.

(v) Although there is no conclusive evidence, it could be argued that a strong code of ethics

helps to create an organisation with a strong sense of values, and that this in the long term

will help to promote its commercial success.

Home Study: For further information on various aspects of ethics, please read chapter

1 in study text

18 Key issues in Corporate Governance

The scope of corporate governance is vast and we shall expand on the following key issues

during this course of study.

Major issues pertaining to corporate governance, that could arise in an exam question, are

illustrated below.

16

SECTION 1: Concepts in Corporate Governance

19 The History of Corporate Governance

Corporate governance issues came to prominence in the UK and Europe In the late 1980s.

One of the main drivers for improvement was an increasing number of high profile corporate

scandals and collapses including Polly Peck International, BCCI, and Maxwell

Communications Corporation

17

SECTION 1: Concepts in Corporate Governance

20 Other counties response to governance issues

.

21 South Africa and the King Reports

South Africa's major contribution to the corporate governance debate has been the King

report, first published in 1994. The King report differs in emphasis from other guidance by

advocating an integrated approach to corporate governance in the interest of a wide range

of stakeholders – embracing the social, environmental and economic aspects of a

company's activities. The report encourages active engagement by companies,

shareholders, business and the financial press and relies heavily on disclosure as a

regulatory measure.

22 The Singapore Code

The Singapore Code (published 2001, revised 2005 and again 2018) of Corporate

Governance takes a similar approach to the UK Corporate Governance Code, comply or

explain why not. Some guidelines, particularly on directors' remuneration, go beyond what is

in UK guidance.

23 The USA and The Sarbanes-Oxley Act 2002

In the US the response to the breakdown of stock market trust caused by the Enron scandal

and others was the Sarbanes-Oxley Act 2002. The Act applies to all companies that are

required to file periodic reports with the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC),

effectively any company in the world listed on the New York Stock Exchange. SOX is a rule

based regime and rule-making authority was delegated to the SEC on many provisions.

24 Governance in the public sector

In addition to the high profile corporate scandals in the early 90’s such as Polly Peck and

BCCI, there were also various scandals involving people in public life such as that revealed

by the Guardian Newspaper in 1994 of MP’s taking bribes to ask questions in the House of

Commons.

This prompted the Prime Minister, John Major, to set up The Committee on Standards in

Public Life headed by Chairman Lord Nolan in 1995. The Committee still meets as it is a

standing committee, generally monthly throughout the year

The committee reported the following year, publishing a set of seven principles

18

SECTION 1: Concepts in Corporate Governance

25 The Seven Principles of Public Life (The Nolan Principles)

Selflessness – Holders of public office should act solely in terms of the public

interest. They should not do so in order to gain financial or other benefits for

themselves, their family or their friends.

Integrity – Holders of public office should not place themselves under any financial

or other obligation to outside individuals or organisations that might seek to influence

them in the performance of their official duties.

Objectivity – In carrying out public business, including making public appointments,

awarding contracts, or recommending individuals for rewards and benefits, holders of

public office should make choices on merit.

Accountability – Holders of public office are accountable for their decisions and

actions to the public and must submit themselves to whatever scrutiny is appropriate

to their office.

Openness – Holders of public office should be as open as possible about all the

decisions and actions they take. They should give reasons for their decisions and

restrict information only when the wider public interest clearly demands.

Honesty – Holders of public office have a duty to declare any private interests

relating to their public duties and to take steps to resolve any conflicts arising in a

way that protects the public interest.

Leadership – Holders of public office should promote and support these principles

by leadership and example.

The committee then published a wide variety of reports concerning specfic areas from Local

Public Spending Bodies, to Local Government and Standards of Conduct in Executive

NDPBs,(Non Departmental Public bodies) and NHS Trusts. Its remit was extended in 1997

to political parties.

There are major differences between corporate governance in the private sector and public

sector, the main one is the public sector is non profit making and accountable to different

stakeholders, there are no shareholders in the public sector.

26 Stakeholders in the not-for-profit sector (example charities)

Primary stakeholders of charities include not only donors and regulators, but also grant

providers, service users and the general public. There may be a conflict between the

objectives of these different stakeholders. Some stakeholders have demanded that charities

should be run on more commercial lines, attempting to make the most of resources and with

chief executives drawn from the private sector. Other stakeholders (volunteers, some

donors) have objected that this has meant charities moving too far away from their charitable

objectives

27 Disclosure by charities

In some regimes charities face a light disclosure regime which allows them to provide

minimal financial detail. Charities have been criticised for this and some has responded by

making fuller disclosures than required by law.

19

SECTION 1: Concepts in Corporate Governance

Good Governance: A Code for the Voluntary and Community Sector was written in 2005 by

representatives from all over the sector, supported by the charities commission in 2005,

Trustees should:

Identify those stakeholders with a legitimate interest in their work.

Have a strategy for regular and effective communication with them about the

organisation's achievements and work.

Communicate planned developments, account for feedback and complaints, and

report performance, impacts and outcome.

The Code sees openness and accountability as meaning:

Being clear about what information is available and what must remain confidential

Complying with reasonable outside requests for information

Being open about the organisation's governance and its strategic reviews

Ensuring stakeholders have the knowledge & opportunity to hold trustees to account

Ensuring the principles of equality and diversity are applied, and that information and

meetings are accessible to all sectors of the community

Some charities demonstrate that they are delivering value to donors and users of the service

by measuring and publishing the contribution they make. Some use a social or

environmental reporting framework, this includes details of how the charity is run and how it

delivers against its terms of reference and its objectives. This can demonstrate

accountability and transparency and increase the confidence of primary stakeholders.

A governance code for charities: Basic principles

The main principles of a good governance code for charitable organisations should set out

the ways in which the board of directors or trustees provide leadership to the organisation.

Members of the board should understand their role and responsibilities, both

collectively and individually. They must understand their legal duties and their

responsibilities with regard to the governing document of the charity. As trustees,

they have a duty to act in the best interests of the beneficiaries of the trust, and all

the trustees must have a clear idea of who are the intended beneficiaries of the

charity.

The trustees of a charity should ensure that the organisation delivers its purpose or

aim. To do this, they must ensure that the purpose remains valid and that this is

delivered by means of a long-term strategy, an agreed operational budget and

monitoring of outcomes and performance.

The board of trustees should work effectively both as individuals and as a team.

There should be arrangements for identifying and recruiting new trustees.

Once appointed, trustees should be given induction so that they understand what the

charity does, how it operates and how it is funded. Where necessary, trustees should

also be given on-going training in relevant issues. A good governance code for

charities should also require that directors or trustees are subject to regular

performance reviews into their effectiveness.

20

SECTION 1: Concepts in Corporate Governance

The trustees should exercise effective control over the charity, and ensure that it

complies with all legal and regulatory requirements, has good financial and

management controls, identifies the major risks facing the charity and has a good risk

management system in place to deal with them. The trustees should also ensure that

authority is delegated to management, committees or volunteers and that the charity

is operating effectively.

The board of a charity should behave with integrity and promote the integrity of the

charity. A charity should also be open and accountable, both internally and

externally. This requirement includes open communications, informing people about

the charity and its work.

Governance away from the public sector and listed companies

Reading: Governance in Unlisted and Private companies

Please read the section in the study text at the end of chapter 5 and the principles suggested

by the Institute of Directors

The BHS scandal

BHS was originally listed and in the FTSE 100, but was purchased outright in 2000 by Sir

Philip Green and taken private, so it became a private limited company again, but a rather

large one.

The business failed, and left a large deficit in the company pension fund, the resulting

scandal concerning how this had occurred meant the Government decided that large limited

companies needed to improve their corporate governance.

They engaged James Wates CBE, who was head of one of the largest privately owned

construction companies in UK. Formed a committee to look at governance of large private

companies and published proposals in July 2018, with the FRC publishing Large Ltd code in

December 2018.

Based on a comply or explain basis, basic governance requirements were suggested for

large limited companies

On 11 June 2018 The Companies (Miscellaneous Reporting) Regulations 2018

were laid in Parliament

This new reporting requirement will apply to financial years beginning 1 January 2019 with

reporting to start in 2020.

Companies will be able to apply the Wates Corporate Governance Principles for Large

Private Companies and meet the requirement.

21

SECTION 1: Concepts in Corporate Governance

It will require private companies of a significant size to disclose their corporate governance

arrangements in their directors’ report and on their website, including whether they follow a

formal code such as the Wates Corporate Governance Principles.

The following criteria apply

•

(i) more than 2,000 employees; or

•

(ii) turnover above 200 million pounds ($267 million) and a balance sheet of more

than 2 billion pounds.

•

Where companies meet these criteria they must publish a statement of their

corporate governance arrangements in their directors' report and website.

The Six Wates Principles were as below:

Purpose – An effective board promotes the purpose of a company, and ensures that

its values, strategy and culture align with that purpose.

Composition – Effective board composition requires an effective chair and a balance

of skills, backgrounds, experience and knowledge, with individual directors having

sufficient capacity to make a valuable contribution. The size of a board should be

guided by the scale and complexity of the company.

Responsibilities – A board should have a clear understanding of its accountability

and terms of reference. Its policies and procedures should support effective decisionmaking and independent challenge.

Opportunity and Risk – A board should promote the long-term success of the

company by identifying opportunities to create and preserve value and establish

oversight for the identification and mitigation of risk.

Remuneration – A board should promote executive remuneration structures aligned

to sustainable long-term success of a company, taking into account pay and

conditions elsewhere in the company.

Stakeholders – A board has a responsibility to oversee meaningful engagement with

material stakeholders, including the workforce, and have regard to that discussion

when taking decisions. The board has a responsibility to foster good relationships

based on the company’s purpose.

22

SECTION 1: Concepts in Corporate Governance

Summary

Key areas

Introduction

Definitions of corporate governance

Stakeholders

Agency theory

Approaches to corporate governance

Principles of governance

Ethics and governance

History of governance

The public sector

Governance of charities

The private sector

23

SECTION 1: Concepts in Corporate Governance

Quick Quiz

1. Name five principles that underlie corporate governance.

2. Fill in the blank, using one of the principles you named above.

........................................ means straightforward dealing and completeness

3. In one sentence “Why is agency a significant issue in corporate governance?”

Longer questions

4 Summarise the main features of agency theory in relation to corporate governance.

(6 marks)

24

SECTION 1: Concepts in Corporate Governance

5 What do you understand by ‘fairness’ in a corporate governance context? (4 marks)

25

SECTION 1: Concepts in Corporate Governance

Answers to Quick Quiz

1 Any five of:

Fairness, Openness/Transparency, Independence,

Accountability, Reputation, Judgement and Integrity

Probity/Honesty,

Responsibility,

2. Integrity

3 Because of the separation of ownership (principal) from management (agent), the

information asymmetry between them and resultant lack of goal congruence.

Answers to longer questions

4 Summarise the main features of agency theory in relation to corporate governance.

(6 marks)

Agency theory may be summarised as follows:

In large companies, ownership is separated from control of the company. Control is

exercised by managers, who act as agents on behalf of the shareholders.

Managers should therefore act in the interests of shareholders, but are actually

driven by self-interest.

Conflicts of interest therefore arise between managers and shareholders, and

managers cannot be relied on to act in the best interests of shareholders, without

controls or incentives.

These problems create costs to shareholders (agency costs). These might be costs

of monitoring (for example, costs of external audits), costs of incentivising

management (bonuses etc.) or costs arising from the fact that managers take some

decisions in their self-interest anyway.

An aim of corporate governance should be to minimise these agency costs.

Credit was given to any mention of the originators of agency theory, Jensen and Mekling.

EXAMINER’S COMMENTS

It is difficult to explain a theory briefly within a short answer, and candidates were given

credit for displaying an awareness of the various key issues. Some candidates, however, did

not know what agency theory was, although this did not prevent them writing at length about

something completely different, such as the shareholder approach to corporate governance.

26

SECTION 1: Concepts in Corporate Governance

5 What do you understand by ‘fairness’ in a corporate governance context? (4 marks)

Fairness in a corporate governance context requires giving equal consideration to each

shareholder and ensuring that the rights of minorities are protected. This involves the

provision of information to all shareholders and providing access to general meetings and

voting arrangements.

Examiner’s comments

This question was often better answered by students outside the UK. Perhaps long tradition

and legislation in the UK has made equal treatment of all investors the natural thing to do?

27

Achievement Ladder Step 1

ACHIEVEMENT LADDER STEP 1

You have now covered the topics that will be assessed in Step 1 of your Achievement

Ladder.

You should now attempt and pass Step 1 of the Achievement Ladder on the online

VLE platform BEFORE moving on to the next part of the course.

It is vital in terms of your progress towards 'exam readiness' that you attempt this Step in the

near future.

You will receive feedback on your performance, and you can use the ongoing BPP support

to help address any improvement areas. This will help you to tailor your learning exactly to

your own individual requirements

Achievement ladder Step 1

10 multiple choice questions

Followed by

Debrief of questions

28

SECTION 2: Principles v Rules

SECTION 2: GOVERNANCE: PRINCIPLES V RULES

1 Development of corporate governance codes

To combat governance problems many jurisdictions have developed voluntary codes of best

practice. Some of the main provisions of codes have been clear attempts to deal with difficult

situations. For example: An individual dominating a company has been countered by

recommendation that different directors occupy the positions of CEO and chairman.

However in certain jurisdictions, notably the USA, the voluntary approach did not seem to be

successful, and in response to the Enron scandal and others, in a move to promote

confidence among investors and the markets, the USA went down the regulatory route. The

Sarbanes-Oxley Act became statute in 2002.

2 Principles or rules?

A continuing debate on corporate governance is whether the guidance should predominantly

be in the form of principles, or whether there is a need for detailed laws or regulations.

The UK Cadbury report suggested that a voluntary code coupled with disclosure would

prove more effective than a statutory code in promoting the key principles of openness,

integrity and accountability.

The Cadbury report also acknowledged the need for codes to go beyond broad principles

and provide some specific guidelines.

Lecture Example 1: Class Exercise/Discussion: Principles or rules

Many international companies are listed on both a US stock exchange (with a rules based

approach) and a European stock exchange (with a principles based approach).

Briefly bullet point a list of the issues facing such a company. (Use the table on the next

page comparing principles v rules to assist)

Solution

29

SECTION 2: Principles v Rules

3 A comparison of the two approaches

30

SECTION 2: Principles v Rules

Although the UK is a principles based regime, there are some aspects of governance that

are regulated, a few examples of these regulations are found in:

a) UK Company law

Powers and duties of directors

Disclosure of directors remuneration

b) EU Directives concerning UK company law

Shareholder rights

Requirement to have an audit committee

c) Insolvency Law and directors liability

Fraudulent trading (CA2006)

Wrongful Trading (IA1986)

d) Criminal Law

Insider dealing (CJA 1993)

Money Laundering

4 Characteristics of a principles-based approach

(a) The approach focuses on objectives (for example: shareholders holding a minority of

shares in a company should be treated fairly) rather than the mechanisms by which these

objectives will be achieved.

(b) A principles-based approach can lay stress on those elements of corporate governance

to which rules cannot easily be applied, such as the requirement to maintain sound systems

of internal control.

(c) Principles-based approaches can applied across different legal jurisdictions rather being

founded in the legal regulations of one country. The OECD guidelines, which we shall cover

later in this section, are a good example of guidance that is applied internationally.

(d) Where principles-based approaches have been established in the form of corporate

governance codes, the recommendations are generally enforced on a comply or explain

basis. However some countries have adopted an apply or explain basis, stating that it will

31

SECTION 2: Principles v Rules

lead to companies applying the principles rather than box ticking. King Code 3 specifically

mentions this issue.

(e) Principles-based approaches have often been adopted in jurisdictions where the

governing bodies of stock markets have had the prime role in setting standards for

companies to follow. Listing rules include a requirement to comply with codes, but because

the guidance is in a form of a code, companies have more flexibility than they would if the

code was underpinned by legal requirements.

The UK governance code states that any explanations given should be adequate and clear:

‘It is recognised that an alternative to following a provision may be justified in particular

circumstances if good governance can be achieved by other means. A condition of doing

so is that the reasons for it should be explained clearly and carefully to shareholders …

In providing an explanation, the company should aim to illustrate how its actual practices

are consistent with the principle to which the particular provision relates, contribute to good

governance and promote delivery of business objectives.’

5 The UK Corporate Governance Code

The origins of the current Code stem from the report of the Committee on the Financial

Aspects of Corporate Governance (the Cadbury Report, 1992) to which was attached a

Code of Best Practice.

It became the Combined Code in 1998, and in 2010 a revised code was published and

renamed The UK Governance Code. There were various revisions notably 2014 and 2016,

then after much consultation the Financial Reporting Council, (FRC has responsibility for the

code), published a very heavily revised code in 2018.

The Code is divided into main principles and provisions. For the main principles a company

has to state how it applies those principles. In relation to the Code provisions a company has

to state whether they comply with the provisions or – where they do not – give an

explanation.

The FRC has also published a revised Guidance on Board Effectiveness document to back

up the code.

Lecture example 1a Reading: Highlights of the 2018 UK Governance Code by

FRC in appendix 1

There are 5 main sections, with 18 principles and 41 provisions, examples of a principle and

some of the provisions are shown below from each section.

1 Board Leadership and Company Purpose

Principles A to E and Provisions 1 to 8

Principle A. A successful company is led by an effective and entrepreneurial board, whose

role is to promote the long-term sustainable success of the company, generating value for

shareholders and contributing to wider society.

32

SECTION 2: Principles v Rules

Provision 1. The board should assess the basis on which the company generates and

preserves value over the long-term. It should describe in the annual report how opportunities

and risks to the future success of the business have been considered and addressed, the

sustainability of the company’s business model and how its governance contributes to the

delivery of its strategy.

2 Division of Responsibilities

Principles F to I and Provisions 9 to 16

Principle F. The chair leads the board and is responsible for its overall effectiveness in

directing the company. They should demonstrate objective judgement throughout their

tenure and promote a culture of openness and debate. In addition, the chair facilitates

constructive board relations and the effective contribution of all non-executive directors, and

ensures that directors receive accurate, timely and clear information.

Provision 9. The chair should be independent on appointment when assessed against the

circumstances set out in Provision 10. The roles of chair and chief executive should not be

exercised by the same individual. A chief executive should not become chair of the same

company. If, exceptionally, this is proposed by the board, major shareholders should be

consulted ahead of appointment. The board should set out its reasons to all shareholders at

the time of the appointment and also publish these on the company website.

Provision 10. The board should identify in the annual report each non-executive director it

considers to be independent. Circumstances which are likely to impair, or could appear to

impair, a non-executive director’s independence include, but are not limited to, whether a

director:

• is or has been an employee of the company or group within the last five years;

• has, or has had within the last three years, a material business relationship with the

company, either directly or as a partner, shareholder, director or senior employee of a body

that has such a relationship with the company;

• has received or receives additional remuneration from the company apart from a director’s

fee, participates in the company’s share option or a performance-related pay scheme, or is a

member of the company’s pension scheme;

• has close family ties with any of the company’s advisers, directors or senior employees;

• holds cross-directorships or has significant links with other directors through involvement in

other companies or bodies;

• represents a significant shareholder; or

• has served on the board for more than nine years from the date of their first appointment.

Where any of these or other relevant circumstances apply, and the board nonetheless

considers that the non-executive director is independent, a clear explanation should be

provided.

Provision 11. At least half the board, excluding the chair, should be non-executive

directors whom the board considers to be independent.

3 Composition, Succession and Evaluation.

Principles J to L and Provisions 17 to 23

33

SECTION 2: Principles v Rules

Principle J. Appointments to the board should be subject to a formal, rigorous and

transparent procedure, and an effective succession plan should be maintained for board and

senior management. (Meaning exec committee or 1st layer below board level inc. co. sec.)

Both appointments and succession plans should be based on merit and objective criteria.

(Ref. equality Act 2010), and, within this context, should promote diversity of gender, social

and ethnic backgrounds, cognitive and personal strengths.

Provision 17. The board should establish a nomination committee to lead the process for

appointments, ensure plans are in place for orderly succession to both the board and senior

management positions, and oversee the development of a diverse pipeline for succession.

A majority of members of the committee should be independent non-executive directors. The

chair of the board should not chair the committee when it is dealing with the appointment of

their successor.

Provision 18. All directors should be subject to annual re-election. The board should set out

in the papers accompanying the resolutions to elect each director the specific reasons why

their contribution is, and continues to be, important to the company’s long-term sustainable

success.

Provision 19. The chair should not remain in post beyond nine years from the date of their

first appointment to the board. To facilitate effective succession planning and the

development of a diverse board, this period can be extended for a limited time, particularly in

those cases where the chair was an existing non-executive director on appointment. A clear

explanation should be provided.

4 Audit, Risk and Internal Control

Principles M to O and Provisions 24 to 31

Principle M. The board should establish formal and transparent policies and procedures to

ensure the independence and effectiveness of internal and external audit functions and

satisfy itself on the integrity of financial and narrative statements (includes interim reports)

Provision 24. The board should establish an audit committee of independent non-executive

directors, with a minimum membership of three, or in the case of smaller companies, two.

(below FTSE 350 throughout the year prior to the reporting year i.e. all of 2019 if reporting

year is 2010) The chair of the board should not be a member. The board should satisfy itself

that at least one member has recent and relevant financial experience. The committee as a

whole shall have competence relevant to the sector in which the company operates.

5 Remuneration

Principles P to R and Provisions 32 to 41

Principle P. Remuneration policies and practices should be designed to support strategy

and promote long-term sustainable success. Executive remuneration should be aligned to