pubs.acs.org/EF

Article

Oxidative Dehydrogenation of n‑Butane to C4 Olefins Using Lattice

Oxygen of VOx/Ce-meso-Al2O3 under Gas-Phase Oxygen-Free

Conditions

Muhammad Y. Khan, Sagir Adamu, Rahima A. Lucky, Shaikh A. Razzak, and Mohammad M. Hossain*

Downloaded via WESTERN UNIV on July 8, 2020 at 19:37:29 (UTC).

See https://pubs.acs.org/sharingguidelines for options on how to legitimately share published articles.

Cite This: Energy Fuels 2020, 34, 7410−7421

ACCESS

Read Online

Metrics & More

Article Recommendations

ABSTRACT: High-performance, fluidizable VOx/Ce-meso-Al2O3 catalysts were prepared by an excessive solvent approach. The

prepared catalysts were characterized using various physicochemical techniques in order to secure desired properties. XRD, Raman,

and FTIR analyses indicated the presence of amorphous VOx phases on Ce-meso-Al2O3. Nitrogen adsorption isotherm analysis

confirmed a mesoporous framework with a high surface area of the catalysts. H2-TPR reduction showed an active and stable behavior

of the catalysts in repeated reduction and oxidation cycles. The NH3-TPD and NH3 desorption kinetics analysis revealed that the

synthesized catalysts have moderate acidities and low activation energies of NH3 desorption, suggesting weak metal−support

interactions. The VOx/Ce-meso-Al2O3 catalysts were evaluated for n-butane oxidative dehydrogenation (BODH) using a fluidized

CREC riser simulator under gas-phase oxygen-free conditions. The reaction time and reaction temperature were varied between 5

and 25 s and 450−575 °C, respectively. It was found that BODH with 0.2 wt % cerium-doped VOx/meso-Al2O3 catalysts gives the

highest selectivity (62.3%) of C4 olefins with a conversion of 10.6% at 450 °C and 5 s. Furthermore, the fluidizable VOx/Ce-mesoAl2O3 catalyst showed a stable performance over repeated feed injections followed by catalyst regeneration cycles for BODH.

catalysts stand as good candidates for BODH.9,11−16 However,

there are still critical issues related to vanadium catalysts that

need to be addressed. For example, the availability of the

desired amorphous vanadium oxide species is one of the key

aspects for achieving high selectivity of desired C4 olefins.11−16

On the other hand, the support type, vanadium oxide−support

interaction, amount of vanadium oxide loading, and method of

catalyst synthesis play important roles in achieving highly

selective catalysts. It has been shown that high vanadium

loadings may yield a nonselective crystalline V2O5 phase for

BODH.17 As a result, limited VOx loadings (5−10 wt %) are

recommended.18 Similarly, it is reported that the doping of NiMoO4 catalysts with highly basic elements of the IA or IIA

groups tends to increase olefin selectivity.19,20 In this respect, it

is speculated that the metal−support interactions and the

acid−basic nature of the support are key factors affecting C4

olefin selectivity.21 To clarify these matters, nickel oxides and

vanadium oxides have been impregnated on the following

supports: Al2O3, SiO2, MCM-41, MgO, ZrO2, USY, Ti-HMS,

and NaY.12,22−27 Among these materials, magnesium oxide

stands as a good support for VOx-based catalysts.28 However,

given the need of improving mechanical strength properties for

fluidizable catalysts, γ-Al2O3 has been considered as a

1. INTRODUCTION

C4 olefins, which include C4 alkenes (1-butene, iso-butene,

and cis-butene) and 1,3-butadiene, are important feedstocks

for the petrochemical industries. These olefins are processed in

the production of variety of polymers and chemicals such as

styrene rubber, nitrile butadiene rubber, polybutadiene,

polyamides, alkylates, and maleic anhydride.1−3 With the

growing world population and improvements in the quality of

human life, demands for the aforementioned products/

chemicals (so does the C4 olefins) have increased significantly,

which are projected to grow further in the coming years.4

Conventionally, C4 olefins are obtained from various sources,

including (i) dehydrogenation of light alkanes, (ii) fluid

catalytic cracking of heavy oils, and (iii) hydrocracking of

hydrocarbon feedstocks.5 Despite their technical maturity, the

conventional processes experience several disadvantages,6−8

such as (i) high-temperature reaction conditions due to the

highly endothermic nature of involved reactions, (ii)

limitations by thermodynamic constraints and low product

selectivity, (iii) severe catalyst deactivation by coke formation,

and (iv) energy-intensive product separations. In this regard,

C4 olefin production via n-butane oxidative dehydrogenation

(BODH) has been considered to be very promising, given the

possibility of addressing the issues related to the conventional

processes.9−11 Nevertheless, the critical challenge for BODH is

to overcome the low yields of the desired C4 olefin products

by developing more selective BODH catalysts.

Keeping the above into consideration, there are studies in

the open literature investigating the various aspects of BODH

catalysts. Among the studied catalysts, vanadium oxide-based

© 2020 American Chemical Society

Received: January 22, 2020

Revised: April 24, 2020

Published: May 1, 2020

7410

https://dx.doi.org/10.1021/acs.energyfuels.0c00220

Energy Fuels 2020, 34, 7410−7421

Energy & Fuels

pubs.acs.org/EF

preferable support for BODH.29−31 Nevertheless, alumina has

a strong acidic character, which leads to low V 2 O 5

dispersions.16 Thus, modification of the γ-Al2O3 support by

doping it with group IIA alkaline elements, such as Mg, Ca, Sr,

and Ba, has been proposed.12 The effect of the addition of

transition metals (Ni, Fe, and Co) on the BiO-γ-Al2O3 support

was also investigated as a catalyst modifier.29−31 It was shown

that the ternary system (including all-metal species Ni, Fe, and

Co) impregnation on the BiO-γ-Al2O3 support improved the

selectivity of butadiene reasonably. An increase in catalyst

activity was linked to the improved basicity of the alumina

support.29 One should, however, notice that this type of γAl2O3 doping remains intrinsically limited given the lack of

catalyst stability.

Furthermore, the selectivity to the desired C4 olefin

products can also be improved by selecting adequate reactor

operating conditions. In this regard, BODH under gas-phase

oxygen-free conditions could be an interesting alternative to

enhance C4 olefin selectivity by suppressing COx formation,

which is similar to the ODH of propane (to propylene) and

ethane (to ethylene), as demonstrated by the present research

group.8,33 This process involves twin interconnected fluidized

bed reactors, (i) a ODH reactor and (ii) catalyst regenerator,

and solid catalyst particles can be circulated between the

fluidized beds. In this approach, the feed n-butane will be

dehydrogenated by reacting with the lattice oxygen of the solid

metal oxide catalyst. The oxygen-depleted catalyst will be sent

to the catalyst regenerator to be reoxidized in contact with air

and recycled back to the ODH reactor.

Given all the abovementioned facts, a new Ce-doped

fluidizable VOx/meso-Ce-Al2O3 catalyst for BODH under

gas-phase oxygen-free conditions has been investigated. The

proposed catalyst is specially tailored for its dual roles: (i)

catalyze the BODH reaction and (ii) act as an oxygen carrier

for the BODH reaction. To accomplish this, cerium is used for

alumina support modification, which upon oxidation, gives a

CeO2 phase. Cerium oxide has outstanding properties to limit

support acidity. Also, ceria tends to increase catalyst thermal

stability and reduces BODH catalyst deactivation. In this

respect, Solsona et al.32 and Khan et al.33 reported improved

catalyst activity of NiO and VOx, respectively, due to the

incorporation of cerium. It is thus proposed that the vanadium

oxide impregnation on cerium-modified alumina in the present

study be prepared using the excessive solvent impregnation

method.34 It is also considered to characterize the developed

BODH catalyst using the following state-of-the-art characterization techniques: XRD, nitrogen adsorption isotherms, TGA,

TPR/TPO, NH3-TPD, FTIR, and Raman as well as NH3

desorption kinetics. Finally, the superior BODH catalyst

performance for n-butane conversion and C4 selectivity

experimental runs were developed in a specially designed

fluidized CREC riser simulator under gas-phase oxygen-free

conditions. This reactor has the special feature of mimicking

the operating conditions of circulating fluidized beds, possible

reactor candidates for this BODH process.

Article

were used without any further purification. Both meso-Al2O3 (MAs)

and Ce-meso-Al2O3 (Ce-MAs) catalyst supports were synthesized

using the facile free method,35,36 which has also been adopted in our

previous work.33,37,38 In the MAs preparation, a 1.0 molar solution of

ammonium carbonate was used to partially hydrolyze 0.1 molar

solution of aluminum nitrate nonahydrate under continuous stirring.

The hydrolysis of the aluminum nitrate solution was continued until a

monolithic gel formation was obtained, which was dried at 30 °C for

24 h. Afterward, the dried gel was heated at a rate of 1 °C/min to 150

and 200 °C for 12 h. Subsequently, MAs crystals were calcined at 300

°C at the same heating rate of 1 °C/min for 12 h. Cerium-doped

alumina supports (Ce-MAs) were synthesized using the same

procedure. However, before the hydrolysis step, an appropriate

amount of cerium nitrate solution (yielding 0.2, 1.0, 3.0, and 5.0 wt %

Ce in MAs) was added to the aluminum salt solution.

The excessive solvent impregnation technique was employed to

impregnate 5 wt % vanadium oxide on all synthesized supports. In a

typical impregnation of VOx, an appropriate weight of vanadium

acetylacetonate salt was dissolved in the excessive volume of toluene

under vigorous stirring. The prepared supports (MAs and Ce-MAs)

were added to this vanadium salt solution and were allowed to mix

under continuous magnetic stirring. After 6 h, the catalyst was

separated from toluene in a centrifuge rotating at 4000 rpm. The

separated catalyst was then heated to 30 °C for 24 h. The dried

sample was then heated (0.5 °C/min) in the furnace at 140 °C for 6

h. The powder catalysts were then reduced in the fluidized conditions

using a gas mixture of H2 and Ar in a vertically mounted Thermocraft

furnace. Subsequently, the reduced catalysts were calcined in the same

furnace at 750 °C for 10 h at a ramping rate of 0.5 °C/min. Table 1

Table 1. Catalyst Designation

VOx/Ce-meso-Al2O3 catalyst composition

no.

wt % V

wt % Ce

wt % meso-Al2O3

nomenclature

1

2

3

4

5

6

0.0

5.0

5.0

5.0

5.0

5.0

0.0

0.0

0.2

1.0

3.0

5.0

100

95

94.8

94

92

90

MAs

0.0 Ce

0.2 Ce

1.0 Ce

3.0 Ce

5.0 Ce

presents the wt % values of different species present in the six different

catalysts prepared in the present study. The wt % values shown in

Table 1 are determined as per the synthesis method. As we can see, all

the cerium-doped catalysts have the same amount of vanadium (5 wt

%) over them; hence, they can be named such that they indicate the

amount of Ce present in them. For the sake of convenience, we have

used the vocabulary of Table 1 throughout this document. For

example, the 0.2 Ce acronym represents the 5.0 wt % VOx/0.2 wt %

Ce-γ-Al2O3 catalyst. The particle size of all the synthesized catalysts

was in a range of 15−110 μm and a Sauter mean diameter of 95 μm.

The sizes of the synthesized catalysts are within the range of group A

of Geldart’s powder classification, which is similar to commercial fluid

catalytic cracking catalysts.

2.2. Catalyst Characterization. The catalysts’ BET (Brunauer−

Emmett−Teller) surface areas and pore properties were measured on

Quantachrome ASIQwin equipment. In the typical experimental

procedure, approximately 150 mg of a catalyst sample was loaded into

a U-tube sample holder, and it was preheated under N2 for 3 h at 350

°C. In the adsorption analysis, the bath temperature was maintained

at 77 K using liquid N2. The specific surface area was determined

using the BET method, and the pore volume and diameter were

derived from the BET isotherm using the Barret−Joyner−Halanda

(BJH) procedure.

X-ray diffraction (XRD) measurements were conducted on a MiniFlex II Rigaku. The equipment is provided with nickel-filtered Cu Kα

radiation with a wavelength =0.15406 nm, 15 mA, and 30 kV. The

2. EXPERIMENTAL SECTION

2.1. Catalyst Synthesis. Cerium nitrate hexahydrate (Ce(NO3)3·

6H2O), aluminum nitrate nonahydrate (Al(NO3)3·9H2O), vanadium

acetylacetonate, toluene, and ammonium carbonate were used in the

synthesis of VOx/Ce-meso-Al2O3 catalysts. The aforementioned

chemicals were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich except for ammonium

carbonate, which was obtained from Fisher Limited. These chemicals

7411

https://dx.doi.org/10.1021/acs.energyfuels.0c00220

Energy Fuels 2020, 34, 7410−7421

Energy & Fuels

pubs.acs.org/EF

Article

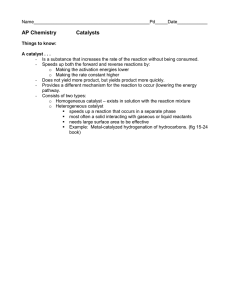

Figure 1. (a) Pictorial view of the main parts of the riser simulator. (b) Schematic diagram of the CREC riser simulator experimental setup.39

°C min−1. The thermal conductivity detector (TCD) was employed

to analyze the exit gas composition. Similarly, NH3-TPD measurements help to determine the total acidity of the powdered samples. In

all TPD analyses, 100 mg of the calcined catalyst was loaded into the

sample holder and was pretreated at 300 °C using He gas for 3 h (30

cm3 min−1). In the subsequent step, the catalyst was heated to 100 °C

in a gas mixture of 5% NH3/He at a flow rate of 50 cm3 min−1 for 1 h.

The gaseous NH3 molecules were flushed out of the catalyst bed by

purging He for an hour at 50 cm3 min−1. NH3 desorption was studied

up to 750 °C with a heating rate of 10 °C min−1 under a He flow rate

of 50 cm3 min−1. NH3 in the effluent stream was monitored using a

TCD detector.

Raman spectrums of the synthesized catalysts were determined on

a Horiba Raman spectrometer (iHR 320). The apparatus is equipped

with a CCD detector that helps to minimize the elastic beam

scattering. In a typical experimental procedure, the following settings

angle of the incident beams was set between 10 and 90° and a step

size of 0.02 with a scanning rate of 3°/min.

Thermogravimetric analyses (TGA) were performed on a TA SDTQ600. TGA measurements help in determining the thermal stability

of the prepared catalysts. In a typical experimental procedure, 10 mg

of the sample was heated at a rate of 10 °C min−1 to 950 °C with a N2

purging flow rate of 100 cm3 min−1.

The H2-TPR (temperature-programmed reduction) and NH3-TPD

(temperature-programmed desorption) experiments were conducted

on a Micromeritics (AutoChem-II) apparatus. Along with the redox

properties, TPR/TPO analyses also help in evaluating the catalyst

stability. In each experimental run, an equal amount of the catalyst

sample (100 mg) was placed in the quartz U-tube. Before the

reduction step, the samples were pretreated in argon (99.9%) at 300

°C for 3 h (50 cm3 min−1). A gas mixture of 5% H2/Ar (50 cm3

min−1) was used for the reduction at 850 °C at a ramping rate of 10

7412

https://dx.doi.org/10.1021/acs.energyfuels.0c00220

Energy Fuels 2020, 34, 7410−7421

Energy & Fuels

pubs.acs.org/EF

were used: excitation λ = 532 nm and laser intensity = 50% at 50−

2500 spectrums. Before the collection of spectrums, each catalyst was

dehydrated for 1 h at 500 °C.

2.3. Reactor System. The n-butane ODH (BODH) reactions

were carried in the fluidized bed CREC riser simulator using only the

lattice oxygen of the catalyst. This mini-batch reactor has a 53 cm3

reaction volume and is specially designed to investigate the ODH

catalyst’s activity and reaction kinetics in a fluidized condition (riser/

downer).39 The reactor is shown in Figure 1, illustrating that the

reactor has two major sections: (a) the upper part and (b) the lower

part. The complete reactor assembly includes the following principal

parts: grids, impellers, heaters, retaining rings, thermocouples, and

cooling jackets. The reactor is connected to the vacuum chamber via

an automatic four-port valve that directs the reaction products to be

collected to the vacuum chamber. An online GC−MS was connected

to the vacuum chamber through a six-port valve to analyze these

reaction effluents.22,40

In all the BODH experiments, 1.0 g of the synthesized catalyst was

loaded into the reactor. Prior to each run, the reactor and vacuum

chamber were purged with Ar gas for 15 min, and a leak test was

conducted. Then, the leakproof reactor’s temperature was increased in

a stepwise manner to a desired reaction temperature value under

continuous flushing with Ar gas to eliminate hot spots and the

atmospheric gas-phase oxygen interface. Upon reaching the temperature set point, the reactor was degassed to 1 atm pressure using a

vacuum pump. Finally, the reaction vessel was disconnected from the

vacuum chamber with the help of an isolation valve. In the following

step, the vacuum chamber pressure was further decreased to 0.26 atm

using a vacuum pump. Before the BODH reactions, the catalyst bed

was fluidized using an impeller rotating at a speed of 5000 rpm. All

BODH experiments were performed in the fluidized bed condition

with no gas-phase oxygenthis is to make sure that only the lattice

oxygen of the catalysts is used. It is possibly important to mention

here that the intense mixing of the small catalyst particles (15−110

μm) and gaseous n-butane (feed) eliminates any possibility of mass

transfer limitations. The BODH reactions were studied in a

temperature range of 450−600 °C, and the resident time was varied

within 5−25 s. The reactor temperature was gradually raised from the

ambient temperature to the desired temperature value under a

continuous flow of Ar. After each experimental run, the spent catalyst

was oxidized with zero air at 575 °C for 10 min, and upon completion

of the regeneration step, the supply of air was stopped. Subsequently,

the reactor was cleaned with argon gas for 15 min. The pure n-butane

(99.97%) is used as a feed in all BODH experiments. All experiments

were performed at a pressure = 1 atm, impeller speed = 4000 rpm

(used for fluidization), and feed-to-catalyst ratio = 1 mL of n-butane/

1.0 g of catalyst. One milliliter or the equivalent of 2.48 mg of pure nbutane was then fed into the reaction chamber via a preloaded airtight syringe.

Upon the completion of the reaction, a valve automatically

connected the reactor with the vacuum chamber. Thus, this allowed

the reaction effluents to be analyzed by an online GC (Agilent

7890A) equipped with FID and TCD detectors. After each BODH

reaction, the used catalyst was reoxidized at 575 °C for 10 min using

zero air. The products of n-butane ODH (BODH) reaction were

identified using an online GC. Further computation with the GC

results enables us to calculate conversion (X) and selectivity (Si) with

the help of the following formulas:

i moles of feed reacted yz

zz × 100

conversion, X (%) = jjj

k moles of n − butane fed {

Article

desorption isotherms of the bare calcined meso-Al2O3 support

and 0.2 Ce and 1.0 Ce catalysts are displayed in Figure 2. The

Figure 2. N2 adsorption isotherms of bare MAs, 0.2 Ce, and 1.0 Ce

samples.

complete nitrogen adsorption isotherm analysis, namely, BET

surface area, BJH pore size, and pore volume, are given in

Table 2 with a cross-correlation coefficient value of >0.99 and

Table 2. BET Surface Area, Pore Volume, and Pore Size of

the Bare Support

catalyst

SBETa (m2/g)

VBJHb (cm3/g)

rBJHc (nm)

MAs

0.0 Ce

0.2 Ce

1.0 Ce

3.0 Ce

5.0 Ce

296

231

152

142

99

88

0.8

0.6

0.4

0.4

0.3

0.2

10.2

9.3

8.4

5.6

4.2

3.6

a

SBET, surface area of the catalyst bVBJH, pore volume crBJH, average

pore width

95% confidence interval. All the analyzed samples showed a

type IV isotherm, assigned to the mesoporous materials that

typically form a monolayer, which is followed by the

multilayers, finally resulting in the capillary condensation that

starts at a relative pressure of ∼0.6. The surface area of the

calcined meso-Al2O3 catalyst support was found to be 296.5

m2g−1, which is within the range of surface area as reported in

the literature35,36 and consistent to the value that the authors

found in previous works.33,34,37 As can be observed in Table 2,

the surface area of the bare MAs decreases from 296.5 to 88.4

m2g−1 for the 5.0 Ce catalyst. Therefore, with an increase in

cerium wt % and an overlayer of vanadium in the catalyst

matrix, the BET surface area, BJH pore width, and BJH pore

volume of all the samples decrease. Thus, more highly doped

catalysts will have a smaller BET surface area. This adverse

effect is due to the breakdown and blockage of the MAs pores,

which are due to the presence of dopant (cerium) and

impregnated overlayer of VOx. The average pore sizes of the

MAs (meso-Al2O3 support) and all other catalysts are in a

range of 2−50 nm, which according to IUPAC nomenclature,

is classified as mesoporous.41 The BET analysis has confirmed

the formation of the high surface area of mesoporous catalysts.

(1)

i moles of product i yz

zzz × 100

selectivity of product i, Si (%) = jjjj

k moles of feed reacted {

(2)

3. RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

3.1. Catalyst Characterizations. 3.1.1. Nitrogen Adsorption Isotherm Analysis. As a reference, the adsorption/

7413

https://dx.doi.org/10.1021/acs.energyfuels.0c00220

Energy Fuels 2020, 34, 7410−7421

Energy & Fuels

pubs.acs.org/EF

Article

This could be related to the excellent performance of the

catalysts in ODH reactions.

3.1.2. X-ray Diffraction. The XRD patterns of the prepared

support and catalysts are shown in Figure 3. The XRD patterns

Figure 4. TPR profiles of the freshly prepared catalysts with varying

amounts of dopant wt %: (a) 0.2 Ce, (b) 1.0 Ce, (c) 3.0 Ce, and (d)

5.0 Ce samples.

Figure 3. XRD patterns of MAs, 0.0 Ce, 0.2 Ce, 1.0 Ce, 3.0 Ce, and

5.0 Ce samples.

of CeO2 in γ-Al2O3 also inhibits the transformation of the γAl2O3 phase to α-Al2O3 phase.46

The H2-TPR profile for the calcined 0.0 Ce catalyst (0.0 wt

% Ce, 5.0 wt % V, and 95.0 wt % γ-Al2O3) showed only one

asymmetric peak extending from 270 to 475 °C. The reduction

observed in the preceding temperature range is assigned to the

monomeric and polymeric reduction of the amorphous VOx

with the oxidation states of V+5 and V+4, respectively.8 A

similar observation of VOx reduction in a temperature range of

280−500 °C was also reported by Reddy and Varma,47

Martinezhuerta et al.,48 and our previous articles.33,47,48 The

cerium-doped 0.2 Ce, 1.0 Ce, 3.0 Ce, and 5.0 Ce catalysts also

displayed low-temperature H2-uptake peaks. However, due to

the presence of both VOx and CeO2 phases (as seen in XRD),

the TPR peak at low temperatures is assigned to the reduction

of both VOx and CeO2 phases. The contribution of CeO2 in

the consumption of H2 is because of the surface reduction of

the CeO2 phase having an oxidation state of Ce+4, as also

observed by Kaŝpar et al.49 Furthermore, the temperature of

the maximal H2-TPR consumption (Tmax1) has increased with

the amount of cerium (dopant) in the support. The increase in

reduction temperature is believed to be due to the formation of

stable monomeric surface species.50 The TGA analysis also

exhibited a similar trend where higher-cerium-containing (3.0

Ce and 5.0 Ce) catalysts showed more excellent thermal

stability.51 Furthermore, in XRD characterizations, 3.0 Ce and

5.0 Ce catalysts showed intense diffraction peaks for the CeO2

phase.

The reduction at high temperatures with the maximum at

800 °C is solely attributed to the bulk reduction of the CeO2

phase, which is only noticeable in 3.0 Ce and 5.0 Ce catalysts,

as presented in Figure 4. The catalyst reduction at high

temperatures shows a strong metal−support interaction.51,52

This high-temperature reduction peak is absent in both 0.2 Ce

and 1.0 Ce catalysts due to a very low Ce concentration

(CeO2) in these catalysts.33 However, as the loading of cerium

increases, so does the formation of the crystalline CeO2 phase,

as previously confirmed by XRD analysis. The increase in

CeO2 formation results in the high-temperature H2 consumption peak.

of the bare MAs exhibit peaks at 2θ = 37.0°, 45.5°, and 67.0°,

corresponding to mesoporous γ-Al2O3 (JCPDS 10-0425).35

The modification of MAs with different cerium wt % values

leads to a change of intensity and shape of XRD peaks of γAl2O3, except for the 0.2 Ce catalyst. As evident in Figure 3, no

diffraction lines for the crystalline CeO2 phase were noticed for

the 0.2 Ce catalyst (0.2 wt % cerium-doped catalyst),

suggesting the amorphous CeO2 phase formation at a low

loading of cerium. With increasing the cerium loading beyond

0.2 wt %, the intensity of the cerium oxide diffraction lines also

increased. According to JCPDS 34-0394, the diffraction lines at

2θ = 28°, 33°, 47.2°, 56.1°, 58.5°, 76.5°, and 79.0° are the

characteristic spectrum of the cubic crystal structure of the

CeO2 phase.42 At a higher loading of cerium (>3.0 wt %) in

the catalyst, the diffraction peaks corresponding to the ceria

phase become well resolved and sharper. The presence of the

intense peaks of CeO2 at higher loadings, i.e., 1.0 Ce, 3.0 Ce,

and 5.0 Ce, decreases the intensity of the main lines of the γAl2O3 support at 2θ = 37.0° and 45.5°.43 Meanwhile, no

diffraction lines were observed for crystalline VOx (besides

MAs, every catalyst is impregnated by 5 wt % vanadium; Table

1), suggesting either crystalline VOx particles are very small

(size of ≤3 nm) and highly dispersed or there is amorphous

VOx phase formation.8,44,45 This will be further discussed in

section 3.1.6 of this article (Raman spectroscopy). Finally, no

diffraction peaks were observed for AlV3O9, which means that

the prepared catalysts are free of solid solution formation

between VOx and MAs, or we can say that there is no solid

reaction between the VOx and MAs.

3.1.3. Reduction of Catalysts by H2-TPR. The H2-TPR

profiles of the calcined samples with different loadings of

cerium (0, 1, 2, 3, and 5 wt %) are depicted in Figure 4.

According to the TPR peaks of the catalysts in Figure 4, 0.0

Ce, 0.2 Ce, and 1.0 Ce catalysts showed only one broad lowtemperature H2 reduction peak in a temperature range of 270−

475 °C, while 3.0 Ce and 5.0 Ce catalysts also showed a hightemperature H2 uptake peak centering at 800 °C. The presence

7414

https://dx.doi.org/10.1021/acs.energyfuels.0c00220

Energy Fuels 2020, 34, 7410−7421

Energy & Fuels

pubs.acs.org/EF

Article

The detailed parameters of the maximum reduction

temperature and total H2 consumption are illustrated in

Table 3. The low-temperature H2 consumption peaks were

Table 3. H2 Consumption of Calcined Catalysts with

Different wt % Values of Cerium (0.0, 0.2, 1.0, 3.0, and 5.0)

low-temperature

samples reduction (Tmax1, °C)

0.0

0.2

1.0

3.0

5.0

Ce

Ce

Ce

Ce

Ce

424.0

430.0

456.5

463.6

473.8

high-temperature

reduction (Tmax2, °C)

total H2

consumption

(cm3 g−1)

796.5

797.0

39.2

35.8

44.3

45.0

48.37

located between 270 and 475 °C, while the higher-temperature

reduction peaks were centered at ∼802 °C. The total H2

consumption for all the synthesized catalysts is the summation

of reductions by VOx and CeO2 phases except for the 0.0 Ce

catalyst. The complete H2 oxidation of 0.0 Ce, 0.2 Ce, and 1.0

Ce is almost comparable due to the presence of the same

loading of VOx (5 wt %) on each cerium-modified support.

However, the highly doped catalysts (3.0 Ce and 5.0 Ce) also

result in the secondary high-temperature reduction peak, which

contributes to more H2 uptake. As previously discussed, H2

consumption at this temperature is due to the bulk reduction

of the CeO2 phase, and from a BODH perspective, the high

percentage of CeO2 is generally unfavorable as it is reported to

promote the complete combustion reactions (CO and CO2).53

The total H2 consumption values given in Table 3 are the

average of the five repeated reduction cycles. All the catalysts

showed a higher H2 consumption during the first cycle of the

reduction, and this is because of a decrease in nitrate species

on the freshly prepared catalysts that tends to increase the H2

consumption. However, with the completion of the first cycle

of reduction, the surface nitrate species are eliminated; thus,

the H2 uptake becomes constant in the rest of the TPR cycles.

Thus, one can predict that 5.0 Ce will be more reactive (will

give the highest HC conversion), but because of the presence

of a high percentage of easily reducible CeO2 species, it may

not be selective for olefin production.

3.1.4. NH3-TPD Analysis. It is generally believed that olefin

selectivity in the ODH reaction mainly depends on the overall

acidity of the catalysts.54,55 NH3-TPD was thus employed to

calculate the total acidity and metal−support interactions. NH3

is widely used for the determination of the aforementioned

properties because of its smaller size and a wide range of

temperature applications.56

The effect of cerium doping on the overall acidity of the

VOx/γ-Al2O3 catalysts can be viewed via NH3-TPD profiles,

displayed in Figure 5. The typical values of maximal desorption

temperatures and total acidity of all samples are summarized in

Table 4. The acidic sites are classified into three main

categories (weak, medium, and strong) based on the maximal

desorption temperature.57,58 All the tested samples showed an

initial broad low-temperature desorption peak at around 195

°C, which is attributed to NH3 desorption from weak acid

sites, whereas a high-temperature desorption peak at ∼544 °C

indicates the NH3 adsorbed on acidic sites with strong acidic

strength.

The synthesized γ-Al2O3 support showed a total acidity of

11.4 cm3 g−1, while the acidity of the unmodified VOx/γ-Al2O3

(0.0% Ce) catalyst was found to be 13.1 cm3 g−1, which is due

Figure 5. NH3-TPD profiles of 0.2 Ce, 1.0 Ce, 3.0 Ce, and 5.0 Ce.

Table 4. NH3-TPD Analyses of MAs and 0.0 Ce, 0.2 Ce, 1.0

Ce, 3.0 Ce, and 5.0 Ce

total acidity

catalysts (cm3 NH3/g cat)

γ-Al2O3

0.0 Ce

0.2 Ce

1.0 Ce

3.0 Ce

5.0 Ce

11.4

13.1

7.6

8.1

10.1

10.7

maximum desorption

temperature for weak

acid sites (°C)

maximum desorption

temperature for

strong acid sites (°C)

200

196

200

196

193

192

395

550

547

543

542

to the acidic nature VOx (Table 4). However, the total acidity

of cerium-modified catalysts (0.2 Ce, 1.0 Ce, 3.0 Ce, and 5.0

Ce) was found to be lower than those of both bare γ-Al2O3 and

VOx/γ-Al2O3. A similar trend of increasing acidity of the

alumina support upon impregnation of VOx has previously

been reported by Al-Ghamdi and de Lasa8 and Datka et al..59

The total acidity of the 0.2 Ce catalyst is 7.64 cm3 g−1; in

comparison with the 0.0 Ce catalyst, the presence of cerium in

the catalyst has significantly reduced the overall acidity of the

VOx/Ce-γAl2O3 catalyst. However, a further increase in the

loading of cerium to 1.0 wt % slightly increases the total

acidity, but still the acidity is lower than those of the bare

support (γ-Al2O3) and cerium-free VOx/γAl2O3 catalyst (0.0

Ce). The slight increase in acidity upon addition of cerium is

assigned to the synergetic effect of both CeO2 and VO2 phases,

promoting more strong acidic sites in comparison to weak

acidic sites, which is reflected by the significant shift of the

high-temperature peak (also the area under the curve). This is

in agreement with our previous work33 and was also observed

by Wu et al.60 and Lee et al.,61 suggesting that a higher loading

of cerium creates new strong acidic sites on the support’s

surface and increases the overall acidity.

3.1.5. NH3-TPD Kinetics. The activation energy (Edes) and

the pre-exponential factor (kdesO) of NH3 desorption were

determined by fitting the NH3-TPD data into the kinetics

model. The knowledge of Edes and kdesO is essential to

understand the metal−support interaction and ease of product

(C4 olefin) desorption from the catalyst pores, respectively.

The estimated kinetics parameters are applicable under the

following assumptions: the single activation energy of

desorption (Arrhenius equation) and Edes are independent of

7415

https://dx.doi.org/10.1021/acs.energyfuels.0c00220

Energy Fuels 2020, 34, 7410−7421

Energy & Fuels

pubs.acs.org/EF

abundant amount of lattice oxygen,45 making them potentially

more active for the reactions (higher conversion in BODH).

However, at a much higher loading of cerium, the catalysts will

become less selective toward BODH reactions due to more

loosely bound lattice oxygen and higher acidity.66 On the other

hand, the catalysts having less cerium wt % (0.2 Ce and 1.0

Ce) require greater energy to desorb NH3, showing relatively

stronger metal−support interactions than the one having a

higher cerium wt % (3.0 Ce and 5.0 Ce). These make them, in

turn, less reactive but highly selective for the BODH reaction

(higher olefin selectivity). Sedor et al. have also demonstrated

a similar trend for the Ni/Al2O3 catalysts, which is the fact that

a catalyst having a small amount of metal oxide results in

higher activation energy, which corresponds to a strong metal−

support interaction.40

It must be pointed out that these TPD kinetics modeling

results agree with the TPR characterization, which showed

higher reactivity for the catalysts with more cerium wt %,

resulting in a higher H2 uptake (see Table 3). XRD

characterization also agrees with the NH3-TPD results by

presenting sharp peaks of CeO2 for 3.0 Ce and 5.0 Ce catalysts

(see Figure 3). According to Trovarelli, the higher concentration of CeO2 wt % in the catalyst, the greater the availability

of the lattice oxygen.46

3.1.6. Raman Spectroscopy. Figure 6 reports the Raman

spectrum of the synthesized catalyst in the range of 100−1200

the surface coverage of adsorbates; there is a uniform

distribution of NH3 concentration over the catalyst bed;

NH3 desorption from the catalyst surface is governed by the

second-order rate process; the desorption process is irreversible (no readsorption); molecular transport and convection

transport resistances are negligible; and the catalyst bed

temperature increases linearly with time.60,62 NH3-TPD

experiments were performed by considering the aforementioned assumptions. The desorption constant (Kd) is given by

Arrhenius’ eq 3. By performing an ammonia balance across the

catalyst bed and after mathematical simplifications, the rate of

desorption (rdes) is given by eq 4

i −E y

Kd = kdesO expjjj des zzz

k RT {

(3)

ij −E ij 1

i dθ y

1 yzyz

n

rdes = −Vmjjjj des zzzz = kdesO θdes

expjjjj des jjj − zzzzzzz

j

Tn z{{

k dT {

k R kT

and

(4)

The change in volume of desorbed NH3 with respect to

temperature can be obtained as63,64

2

ij E ij 1

kdesO ijj

Vdes yzz

ij dVdes yz

1 yzyz

jj

zz =

jjj1 −

zzz expjjjj− des jjjj − zzzzzzzz

β k

Vm {

Tn {{

k dT {

k R kT

Article

(5)

where θdes, Vm, Tn, n, and β represent the catalyst surface

coverage, monolayer volume, centering temperature, order of

desorption process, and heating rate, respectively. Equation 5

was fitted to experimental data by a NonlinearModelFit builtin function in Mathematica. All NH3-TPD data were obtained

using a catalyst mass = 0.1 g and β = 10 °C min−1. The

desorption parameters given in Table 5 were estimated with a

correlation constant value (R2) > 0.99, confidence interval =

95%, degree of freedom = 3769, and large negative Akaike

Information Criterion (AIC) value.

Table 5. Estimated Kinetics Parameters at a Heating Rate of

β = 10 °C min−1

samples

0.0

0.2

1.0

3.0

5.0

Ce

Ce

Ce

Ce

Ce

Edes (kJ/mol)

R2

AIC

Vdes (mL/g cat)

±

±

±

±

±

0.99

0.99

0.99

0.99

0.99

−46,361

−45,379

−41,149

−44,664

−38,882

13.1

7.6

8.1

10.1

10.7

28.0

19.7

14.3

11.6

11.3

0.1

0.1

0.1

0.1

0.1

Figure 6. Raman spectrums of MAs, 0.0 Ce, 0.2 Ce, 3.0 Ce, and 5.0

Ce catalysts.

cm−1. The absence of Raman peaks for MAs is because of the

ionic characteristic of the Al−O bond.67 The VOx spectrum

not only is a function of the vanadium loading but also

depends on the type and concentration of the surface species.

In the 0.2 Ce catalyst, the only weak band is detected at 1130

cm−1. This spectrum of VOx at 1130 cm−1 is almost invisible in

the 0.0 Ce catalyst. The transmittance in the 1130 cm−1 region

is assigned to the widely spread surface species of

monovanadate with an isolated tetrahedral geometry. The

3.0 Ce and 5.0 Ce catalysts also exhibit a similar Raman band

at 1130 cm−1 but with a much higher intensity of the line. The

5.0 Ce catalyst also shows the second Raman band in 950 cm−1

due to the V−O−V bond, suggesting crystalline V2O5 phase

formation. However, no XRD lines were detected for V2O5

crystals, possibly due to their tiny sizes. Thus, the 5.0 Ce

catalyst showed the presence of both polyvanadate and

monovanadate surface species.17 Raman spectroscopic analysis

In Table 5, lower desorption energies for all cerium-doped

catalysts (0.2 Ce, 1.0 Ce, 3.0 Ce, and 5.0 Ce) are noticed as

compared with the cerium-free catalyst (0.0 Ce). Furthermore,

the calculated desorption energies are also lower than those

reported in the literature by Bakare et al. for VOx/γ-Al2O3

catalysts.45 The lower desorption energies mean that less

energy is required to desorb the absorbed NH3 molecules from

the catalyst’s pores, suggesting weaker metal−support interactions. The estimated desorption energies in the present study

lie between the range reported in the literature.45,64,65 In

comparison to the 0.0 Ce catalyst, cerium-doped catalysts

generally will be more selective for the BODH because it will

easily desorb the olefins. The catalysts with more cerium wt %

(3.0 Ce and 5.0 Ce) relatively require the least activation

energy for desorption, which in turn corresponds to the

7416

https://dx.doi.org/10.1021/acs.energyfuels.0c00220

Energy Fuels 2020, 34, 7410−7421

Energy & Fuels

pubs.acs.org/EF

Article

is in complete harmony with XRD analysis (see Figure 3) and

H2-TPR experiments (see Table 3). The increase in cerium

loading in the catalysts reduces the dispersion of the VOx that

promotes the formation of the VOx crystalline phase. The

Raman spectrum for the CeO2 phase appeared at 460 cm−1

wavenumbers, and the intensity of the CeO2 line increases with

cerium wt % in the catalyst; a good resolve peak can be easily

seen in the spectra of 3.0 Ce and 5.0 Ce catalysts. The band at

460 cm−1 corresponds to the CeO2 phase with a fluorite

structure, which was also confirmed by the XRD characterization (see Figure 3).68

3.2. ODH in the CREC Riser Simulator. Prior to the

actual BODH experiments, different thermal runs were

conducted to determine the possible contribution of pyrolysis

to the total yield of desired products. These blank runs were

performed on the empty reactor at 10 s residence time and

within the temperature range of 450−600 °C. Figure 7

Figure 8. Effect of cerium loading on n-butane conversion, C4 olefin

selectivity (including all the isomers, iso-butylene, 1-butene, 2-butene,

etc.), and COx selectivity at 500 °C (standard deviation within ±2.5%

of replicate experiments (w = 1.0 g, feed = 1 mL, t = 10 s)).

the 0.2 Ce catalyst (50.2%). The lower C4 olefin selectivity

over the 0.0 Ce (5.0 wt % VOx/γ-Al2O3) catalyst is mainly due

to its higher acidity, which promotes cracking reactions. On

the contrary, the 0.2 Ce catalyst had previously shown the least

acidic nature (see Table 4), so it minimizes the cracking

reactions and, in return, promotes C4 olefin selectivity. That is

why a higher C4 olefin yield is observed over the 0.2 Ce

catalyst (7.7%) as compared with the 0.0 Ce catalyst (6.2%).

Among the Ce-promoted VOx/Ce-γ-Al2O3 catalysts, the

highest C4 olefin selectivity of 50.2% with 15.4% conversion is

obtained by the 0.2 Ce catalyst (0.2 wt % cerium-doped VOx/

γ-Al2O3). With a further increase in cerium content, there is

both an augmented n-butane conversion and COx selectivity.

One can also notice a trend toward lower C4 olefin selectivity

at a higher amount of cerium-containing catalysts. For

example, the 5.0 Ce catalyst showed the lowest C4 olefin

selectivity of 30.1% with the highest n-butane conversion of

22%.

Figure 8 results can be supported using both TPD and TPR

characterization data. TPR demonstrates that higher CeO2

leads to more reducible species on the surface of the catalyst

and higher lattice oxygen availability (as shown in Table 3 with

the higher H2 uptake). The higher H2 consumption means

more reactivity. Also, TPD provides lower desorption energies,

suggesting less metal−support interactions, making them more

reactive for n-butane conversion. That is why a higher

conversion is observed on 5.0 Ce and 3.0 Ce catalysts as

compared to 0.2 Ce and 1.0 Ce catalysts. Raman and XRD

analyses revealed a greater concentration of the CeO2 phase on

5.0 Ce and 3.0 Ce catalysts. The contact of these catalysts with

n-butane results in the formation of more COx because of the

easily reducible CeO 2 phase, which favors complete

combustion reactions. Similarly, trends of lower alkane

selectivity with higher loadings of cerium have also been

reported by Martin et al.,19 Maldonado-Hodar et al.,20 and Xu

et al.12 The higher-cerium-containing catalysts have revealed

higher acidity (see TPD Table 4), which favors the cracking

reactions and gives <C4 hydrocarbons (HC). Once <C4 HC

have formed, these degraded fractions react in an unselective

manner with the lattice oxygen and result in the formation of

Figure 7. n-Butane conversion vs temperature for thermal blank runs

(standard deviation within ±2.5% of replicate experiments (w = 1.0 g,

feed = 1 mL, t = 10 s)).

illustrates a direct correlation between n-butane conversion

and reaction temperature, provided that the reaction is

performed anaerobically. The lower conversion values

(<3.5%) depicted in Figure 7 suggest that pyrolysis of nbutane would have a negligible effect on BODH reactions. In

particular, also for a selected temperature of 450 °C and

reaction time of 10 s, it was noticed that the thermal n-butane

conversion was limited to 1.2%. Therefore, based on the

thermal blank runs, n-butane conversion in the BODH

reactions will solely be attributed the VOx/Ce-MAs catalysts.

Figure 8 reports the effect of cerium loading on VOx/Ce-γAl2O3 performance under anaerobic conditions at 500 °C and

10 s. It can be observed that the 0.0 Ce (VOx/γ-Al2O3) catalyst

gives a 17.4% n-butane conversion with a 35.5% C4 olefin

selectivity (including all the isomers, iso-butylene, 1-butene, 2butene, etc.) and 42% COx selectivity. Coke was not

considered in selectivity calculation because of its minimal

concentration. The availability of oxygen in the catalyst helps

to minimize coke formation.45 It appears that the 0.0 Ce

catalyst shows a slightly higher n-butane conversion (2%) than

the 0.2 Ce catalyst, which is due to a higher BET surface area

of this catalyst (230.8 m2 g−1). However, C4 olefin selectivity

of the 0.0 Ce catalyst is significantly lower (35.5%) than that of

7417

https://dx.doi.org/10.1021/acs.energyfuels.0c00220

Energy Fuels 2020, 34, 7410−7421

Energy & Fuels

pubs.acs.org/EF

more COx.12,19,20 The indirect formation of COx on 5.0 Ce

and 3.0 Ce catalysts also contributes to higher COx selectivity.

On the other hand, the catalysts containing lesser cerium

(0.2 Ce and 1.0 Ce catalysts) have strong metal−support

interactions, as shown by the small uptake of H2 and higher

desorption energy (see TPD kinetics Table 5), suggesting

lower conversion due to more compactness for lattice

oxygen.8,9,17 However, higher C4 olefin production on 0.2

Ce and 1.0 Ce catalysts is again due to lower acidity (less

formation of <C4 HC) and more selective surface oxide

species.66 Based on the highest C4 olefin yield/selectivity

observed on the 0.2 Ce catalyst, as revealed in Figure 8, only

the 0.2 Ce catalyst will be investigated in the subsequent part

of the present study.

The typical product distribution for the BODH over the two

extreme conditions of the temperature (450 and 600 °C) on

the 0.2 Ce catalyst is shown in Figure 9. The BODH products

Article

Owens, Owen et al., Patel and Andersen, and Armendariz et

al.16,66,69,70 Therefore, the elevated reactor’s temperature

makes both n-butane and C4 olefins more vulnerable to

form cracking products (<C4 hydrocarbons), which upon

complete oxidation, result in COx.71

The performance of the 0.2 Ce catalyst is further assessed by

studying the effect of residence time on the selectivity of C4

olefins, keeping constant reaction temperatures (450 °C and

550 °C), as shown by Figure 10. A similar trend is noted, as

Figure 10. C4 olefin selectivity and n-butane conversion vs reaction

time at various reaction temperatures (deviation within ±2.5% of

replicate experiments; w = 1.0 g, feed = 1 mL).

previously represented by the effect of temperature on product

selectivity (see Figure 9). Although C4 olefins are the main

reaction product, their selectivity decreased significantly with

an increase in contact time. At a reaction time of 5 s and 450

°C, the maximum selectivity of 62.4% is obtained for C4

olefins; whereas, the 25 s and 550 °C reaction conditions give

the lowest C4 olefin selectivity of 28.1%. We can conclude that

long residence times favor conversion of the feed; that is, the

longer contact time of the hydrocarbons with the lattice

oxygen of the catalyst, the higher the concentration of

byproducts (COx and <C4 hydrocarbons). A similar trend is

also reported by Volpe et al. and Cavani et al. that at long

residence times, there is more possibility of direct and indirect

complete combustion of n-butane and C4 olefins, respectively.22,72 It is obvious that the selectivity of COx follows the

reverse trend (higher concentration COx at higher residence

time), as compared with the selectivity of C4 olefins. It was

found in the present study that elevated reaction temperatures

and longer residence contact times favor the COx formation.

As mentioned before, this is because of an increase in the rate

of (1) direct complete oxidation of n-butane, (2) combustion

of formed C4 olefins to COx, and (3) indirect formation of

COx by complete oxidation of cracked products (<C4 HC)

with the unselective lattice oxygen of the catalyst.

Figure 11 illustrates four successive BODH reactions

performed at the same operating conditions (residence time

= 5 s, temperature = 450 °C, and catalyst = 0.2 Ce). As in

BODH reactions, only the lattice oxygen of the catalyst is

consumed; therefore, after each experimental run, the spent

catalyst was regenerated (oxidized in air at 575 °C for 10 min),

which is used for subsequent BODH runs. These experiments

are important as they demonstrate the reproducibility of results

and, hence, the consistent nature of catalysts. Previously, the

Figure 9. Typical product distribution of BODH reaction at 450 and

600 °C over 0.2 Ce (standard deviation within ±2.5% of replicate

experiments (w = 1.0 g, feed = 1 mL, t = 10 s)).

include methane, ethane, ethylene, propane, propylene, COx,

and C4 olefins, while it is clear that C4 olefins and COx (CO +

CO2) are the main reaction products. Figure 9 illustrates the

negative effect of reaction temperature on the selectivity of C4

olefins. This is a typical trend in BODH reactions, as stated by

Madeira and Portela that low temperatures result in higher

olefin selectivity.6 We have also noticed a similar behavior in

which a low temperature corresponds to a lower feed

conversion but results in higher selectivity of C4 olefins.

Therefore, we can conclude, as said in previous literature, that

a low reaction temperature favors olefin formation over the 0.2

Ce catalyst. However, at high reaction temperatures, exactly an

opposite trend was observed. An elevated reaction temperature

supports the feed conversion at the expense of olefin

selectivity. As seen in Figure 9, the higher n-butane conversion

at 600 °C contributes more toward COx and cracking product

(<C4 hydrocarbons) formation, indicating that higher reaction

temperatures make catalysts more selective for unwanted

products (COx and <C4 hydrocarbons).9 The reason for

higher conversion is because of the more activation of C−H

bonds of n-butane and C4 olefins, which results in a higher

concentration of COx and degradation products in the effluent

stream. This behavior has also been reported by Kung and

7418

https://dx.doi.org/10.1021/acs.energyfuels.0c00220

Energy Fuels 2020, 34, 7410−7421

Energy & Fuels

pubs.acs.org/EF

520 °C displaying a 56% C4 olefin selectivity at a 5% n-butane

conversion in a fixed-bed reactor under a gas-phase oxygen-free

environment.27 Comparable selectivity results were achieved

by Lemonidou et al.,73Rubio et al.,75 Dejoz et al. using

magnesium-based catalysts.76

It is however argued that in order to achieve a stable BODH

catalytic process, its implementation in circulating fluidized

beds requires a limitation on the catalyst flow. Table 5 shows

that the VOx/Ce-γAl2O3 (0.2 Ce) catalyst of the present study

achieves at 450 °C a 62.4% C4 olefin selectivity at a 10.7% nbutane conversion. The promising performance is accomplished under gas-phase oxygen-free conditions and low coke

formation (less than 1.3 wt %). Thus, this BODH catalyst

displays great stability under repeated n-butane injections. This

commendable activity of BODH at 450 °C, confirmed using

TPR analysis, can be assigned to the high catalyst specific

surface area and high density of active sites. As a result, this

BODH catalyst appears to be very suitable for continuous

circulating fluidized operation at 450 °C, with minimal catalyst

regeneration in between BODH cycles.

Figure 11. C4 olefin selectivity and n-butane conversion for

successive BODH with interstage catalyst reoxidation over 0.2 Ce

(standard deviation within ±2.5% of replicate experiments (w = 1.0 g,

feed = 1 mL, T = 450 °C, t = 5 s)).

4. CONCLUSIONS

The effect of cerium doping on fluidizable VOx/γ-Al2O3

catalysts was investigated both using surface science characterization and the gas-phase oxygen-free BODH in a CREC riser

simulator batch reactor. The following are the main findings:

(i) BET analysis revealed a mesoporous framework with a

high specific surface area. An inverse relationship

between the specific surface area and cerium content

was also noticed.

(ii) XRD and Raman analyses show no peaks for the

crystalline V2O5 phase, confirming the formation of a

highly dispersed amorphous phase. For cerium, a

crystalline CeO2 phase was confirmed in the 3.0 and

5.0 Ce-doped catalysts.

(iii) TPR/TPO characterization displayed low- and hightemperature H2 reduction peaks for all the prepared

catalysts, while the cyclic TPR/TPO and TGA showed a

stable catalytic performance and thermal stability for the

synthesized catalysts, respectively.

(iv) The coexistence of both strong and weak acidic sites has

been observed during NH3-TPD characterization. The

NH3-TPD kinetics studies have shown a relatively weak

metal−support interaction for the synthesized catalysts

with activation energy of ammonia desorption following

the subsequent trend: 5.0 Ce < 3.0 Ce < 1.0 Ce < 0.2 Ce

< 0.0 Ce.

(v) Among the synthesized catalysts, the 0.2 Ce catalyst

showed a maximum selectivity of 62.4% (C4 olefin) at

450 °C and 5 s. Furthermore, the best catalytic

performance was observed at low reaction temperatures

and shorter residence times.

(vi) The cerium-modified VOx/γ-Al2O3 displayed very low

coke levels at 450 °C and 5 s reaction time, making it

very adequate for its applications in continuous

circulating fluidized bed operation.

repeated TPR/TPO characterizations of the catalysts have also

indicated the stable performance of the catalysts (see Table 3).

Table 6 reports the comparison of the performance of the

BODH catalyst of the current work with others reported in the

Table 6. Comparison of BODH Catalyst Performance

catalyst

VOx/CeγAl2O3

VOx/MCM41

V2O5/MgOAl2O3

V2O5/MgOZrO2

VOx/USY

VOx/USY

Xa

(%)

Tb

(°C)

tc

Sd

(%)

reactor

system

10.7

450

5s

62.4

47.4

550

1h

57

fluidized

bed

fixed bed

Wang et al.25

30.3

600

64.3

fixed bed

Xu et al.12

32.9

500

6h

43.1

fixed bed

Lee et al.74

5

520

4

56

fixed bed

Garcia et al.27

68

fixed bed

Volpe et al.22

Lemonidou et

al.73

Rubio et al.75

Dejoz et al.76

min

8.2

520

4

min

V2O5/MgO

29.5

520

54

fixed bed

V2O5/MgO

MoO3V2O5/

MgO

31.8

24.2

500

550

55.8

69.5

fixed bed

fixed bed

Article

reference

this work

a

X, n-butane conversion bT, reaction temperature ct, reaction time dS,

selectivity of C4 olefins

literature. The comparison is based on C4 olefin production.

Wang et al. obtained 57% C4 olefin selectivity at 47.4% nbutane conversion at 550 °C using VOx/MCM-41 catalysts in

a fixed-bed reactor.25 Similarly, Xu et al. have revealed 30.3% nbutane conversion with 64.3% C4 olefin selectivity using a 5%V2O5/MgO-Al2O3 catalyst at 600 °C in a fixed-bed reactor.12

In a separate study by Volpe et al., VOx as an active metal was

impregnated on the surface of USY, α-Al2O3, NaY, and γ-Al2O3

catalyst supports. Among these catalysts, VOx/USY showed

the best catalytic activity of 68% C4 alkene selectivity with a

8.2% n-butane conversion at 520 °C. In their analysis, gasphase O2-free conditions in a fixed-bed reactor were used.22

Furthermore, Garcia et al. also reported a VOx/USY catalyst at

■

AUTHOR INFORMATION

Corresponding Author

Mohammad M. Hossain − Department of Chemical

Engineering and Center of Research Excellence in

Nanotechnology, King Fahd University of Petroleum and

7419

https://dx.doi.org/10.1021/acs.energyfuels.0c00220

Energy Fuels 2020, 34, 7410−7421

Energy & Fuels

pubs.acs.org/EF

(15) Rischard, J.; Antinori, C.; Maier, L.; Deutschmann, O.

Oxidative dehydrogenation of n-butane to butadiene with Mo-VMgO catalysts in a two-zone fluidized bed reactor. Appl. Catal. A Gen.

2016, 511, 23−30.

(16) Owens, L.; Kung, H. H. The Effect of Loading of Vanadia on

Silica in the Oxidation of Butane. J. Catal. 1993, 144, 202.

(17) Wachs, I. E.; Weckhuysen, B. M. Structure and reactivity of

surface vanadium oxide species on oxide supports. Appl. Catal. A Gen.

1997, 157, 67−90.

(18) Chaar, M. A.; Patel, D.; Kung, M. C.; Kung, H. H. Selective

oxidative dehydrogenation of butane over V-Mg-O catalysts. J. Catal.

1987, 105, 483−498.

(19) Martin-Aranda, R. M.; Portela, M. F.; Madeira, L. M.; Freire, F.;

Oliveira, M. Effect of alkali metal promoters on nickel molybdate

catalysts and its relevance to the selective oxidation of butane. Appl.

Catal. A, Gen. 1995, 127, 201−217.

(20) Maldonado-Hódar, F. J.; Palma Madeira, L. M.; Farinha

Portela, M. The Effects of Coke Deposition on NiMoO4Used in the

Oxidative Dehydrogenation of Butane. J. Catal. 1996, 164, 399−410.

(21) Blasco, T.; Nieto, J. M. L.; Dejoz, A.; Vazquez, M. I. Influence

of the Acid-Base Character of Supported Vanadium Catalysts on

Their Catalytic Properties for the Oxidative Dehydrogenation of nButane. J. Catal. 1995, 157, 271−282.

(22) Volpe, M.; Tonetto, G.; de Lasa, H. Butane dehydrogenation

on vanadium supported catalysts under oxygen free atmosphere. Appl.

Catal. A Gen. 2004, 272, 69−78.

(23) Bhattacharyya, D.; Bej, S. K.; Rao, M. S. Oxidative

dehydrogenation of n-butane to butadiene. Appl. Catal. A Gen.

1992, 87, 29−43.

(24) Wan, C.; Cheng, D.; Chen, F.; Zhan, X. Characterization and

kinetic study of BiMoLax oxide catalysts for oxidative dehydrogenation of 1-butene to 1,3-butadiene. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2015, 135, 553−

558.

(25) Wang, X.; Zhou, G.; Chen, Z.; Jiang, W.; Zhou, H. In-situ

synthesis and characterization of V-MCM-41 for oxidative dehydrogenation of n-butane. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2016, 261−267.

(26) Setnička, M.; Č ičmanec, P.; Bulánek, R.; Zukal, A.; Pastva, J.

Hexagonal mesoporous titanosilicates as support for vanadium oxide Promising catalysts for the oxidative dehydrogenation of n-butane.

Catal. Today 2013, 204, 132−139.

(27) Garcia, E. M.; Sanchez, M. D.; Tonetto, G.; Volpe, M. A.

Preparation of USY zeolite supported catalysts from V(AcAc)3 and

NH4VO3. Catalytic eproperties for the dehydrogenation of n-butane

in oxygen-free atmosphere. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2005, 292, 179−

185.

(28) Corrna, A.; Nieto, J. M. L.; Parades, N.; Dejoz, A.; Vazquez, I.

Oxidative Dehydrogenation of Propane and N-Butane on V-Mg Based

Catalysts. Stud. Surf. Sci. Catal. 1994, 82, 113−123.

(29) Tanimu, G.; Jermy, B. R.; Asaoka, S.; Al-Khattaf, S.

Composition effect of metal species in (Ni, Fe, Co)-Bi-O/gammaAl2O3 catalyst on oxidative dehydrogenation of n-butane to butadiene.

J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 2017, 45, 111−120.

(30) Rabindran Jermy, B.; Asaoka, S.; Al-Khattaf, S. Influence of

calcination on performance of Bi−Ni−O/gamma-alumina catalyst for

n-butane oxidative dehydrogenation to butadiene. Catal. Sci. Technol.

2015, 5, 4622−4635.

(31) Jermy, B. R.; Ajayi, B. P.; Abussaud, B. A.; Asaoka, S.; AlKhattaf, S. Oxidative dehydrogenation of n-butane to butadiene over

Bi−Ni−O/γ-alumina catalyst. J. Mol. Catal. A: Chem. 2015, 400,

121−131.

(32) Solsona, B.; Concepción, P.; Hernández, S.; Demicol, B.; Nieto,

J. M. L. Oxidative dehydrogenation of ethane over NiO−CeO2 mixed

oxides catalysts. Catal. Today 2012, 180, 51−58.

(33) Khan, M. Y.; Al-Ghamdi, S.; Razzak, S. A.; Hossain, M. M.; de

Lasa, H. Fluidized bed oxidative dehydrogenation of ethane to

ethylene over VOx/Ce-γAl2O3 catalysts: Reduction kinetics and

catalyst activity. Mol. Catal. 2017, 443, 78−91.

(34) Elbadawi, A. H.; Khan, M. Y.; Quddus, M. R.; Razzak, S. A.;

Hossain, M. M. Kinetics of oxidative cracking of n-hexane to olefins

Minerals, Dhahran 31261, Saudi Arabia; orcid.org/00000002-7780-5910; Phone: +966-13-860-1478;

Email: mhossain@kfupm.edu.sa; Fax: +966-13-860-4234

Authors

Muhammad Y. Khan − Department of Chemical Engineering,

King Fahd University of Petroleum and Minerals, Dhahran

31261, Saudi Arabia

Sagir Adamu − Department of Chemical Engineering, King Fahd

University of Petroleum and Minerals, Dhahran 31261, Saudi

Arabia

Rahima A. Lucky − Department of Chemical and Biochemical

Engineering, University of Western Ontario, London, Ontario

N6A 3K7, Canada

Shaikh A. Razzak − Department of Chemical Engineering, King

Fahd University of Petroleum and Minerals, Dhahran 31261,

Saudi Arabia

Complete contact information is available at:

https://pubs.acs.org/10.1021/acs.energyfuels.0c00220

Notes

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

■

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The author(s) would like to acknowledge the support provided

by the Deanship of Scientific Research (DSR) at King Fahd

University of Petroleum & Minerals (KFUPM) for funding this

work through project no. IN161022.

■

Article

REFERENCES

(1) White, W. C. Butadiene production process overview. Chem.Biol. Interact. 2007, 166, 10−14.

(2) Yan, W.; Kouk, Q. Y.; Luo, J.; Liu, Y.; Borgna, A. Catalytic

oxidative dehydrogenation of 1-butene to 1,3-butadiene using CO2.

Catal. Commun. 2014, 46, 208−212.

(3) Grasselli, R. K. Fundamental principles of selective heterogeneous oxidation catalysis. Top. Catal. 2002, 21, 79−88.

(4) Sattler, J. J. H. B.; Ruiz-Martinez, J.; Santillan-Jimenez, E.;

Weckhuysen, B. M. Catalytic Dehydrogenation of Light Alkanes on

Metals and Metal Oxides. Chem. Rev. 2014, 114, 10613−10653.

(5) Bender, M. An Overview of Industrial Processes for the

Production of Olefins - C4 Hydrocarbons. ChemBioEng Rev. 2014, 1,

136−147.

(6) Madeira, L. M.; Portela, M. F. Catalytic oxidative dehydrogenation ofn-butane. Catal. Rev. 2002, 44, 247−286.

(7) Fahim, M. A.; Alsahhaf, T. A.; Elkilani, A. Fundamentals of

Petroleum Refining; Elsevier: 54, , 2010.

(8) Al-Ghamdi, S. A.; de Lasa, H. I. Propylene production via

propane oxidative dehydrogenation over VOx/γ-Al2O3 catalyst. Fuel

2014, 128, 120−140.

(9) Kung, H. H. Oxidative Dehydrogenation of Light (C2 to C4)

Alkanes. in Advances in Catalysis; 1994, volume 40, 1−38.

(10) Cavani, F.; Trifirò, F. Partial oxidation of C2 to C4 paraffins. in

Basic Principles in Applied Catalysis; 2004, 75, 19−84.

(11) Blasco, T.; Nieto, J. M. L. Oxidative dyhydrogenation of short

chain alkanes on supported vanadium oxide catalysts. Appl. Catal. A

Gen. 1997, 157, 117−142.

(12) Xu, B.; Zhu, X.; Cao, Z.; Yang, L.; Yang, W. Catalytic oxidative

dehydrogenation of n-butane over V2O5/MO-Al2O3 (M = Mg, Ca, Sr,

Ba) catalysts. Chinese J. Catal. 2015, 36, 1060−1067.

(13) Vedrine, J. C. Heterogeneous catalytic partial oxidation of lower

alkanes (C1−C6) on mixed metal oxides. J. Energy Chem. 2016, 25,

936−946.

(14) Wang, C.; et al. Vanadium Oxide Supported on Titanosilicates

for the Oxidative Dehydrogenation of n-Butane. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res.

2015, 54, 3602−3610.

7420

https://dx.doi.org/10.1021/acs.energyfuels.0c00220

Energy Fuels 2020, 34, 7410−7421

Energy & Fuels

pubs.acs.org/EF

over VOx/Ce-Al2O3 under gas phase oxygen-free environment. AIChE

J. 2017, 63, 130−138.

(35) Shang, X.; et al. Facile strategy for synthesis of mesoporous

crystalline γ-alumina by partially hydrolyzing aluminum nitrate

solution. J. Mater. Chem. 2012, 22, 23806.

(36) Wang, J.; Shang, K.; Guo, Y.; Li, W.-C. Easy hydrothermal

synthesis of external mesoporous γ-Al2O3 nanorods as excellent

supports for Au nanoparticles in CO oxidation. Microporous

Mesoporous Mater. 2013, 181, 141−145.

(37) Adamu, S.; Khan, M. Y.; Razzak, S. A.; Hossain, M. M. Ceriastabilized meso-Al2O3: synthesis, characterization and desorption

kinetics. J. Porous Mater. 2017, 24, 1343−1352.

(38) Elbadawi, A. H.; Khan, M. Y.; Quddus, M. R.; Razzak, S. A.;

Hossain, M. M. Kinetics of oxidative cracking of n-hexane to olefins

over VOx /Ce-Al2O3under gas phase oxygen-free environment. AIChE

J. 2017, 63, 130−138.

(39) De Lasa, H. I. Canadian Patent 1,284,017,(1991). USA Pat 5,

(1992).

(40) Sedor, K. E.; Hossain, M. M.; de Lasa, H. I. Reactivity and

stability of Ni/Al2O3 oxygen carrier for chemical-looping combustion

(CLC). Chem. Eng. Sci. 2008, 63, 2994−3007.

(41) Do, D. D. Adsorption Analysis: Equilibria and Kinetics. Chemical

Engineering; 2, (Imperial College Press: 1998).

(42) Bortolozzi, J. P.; Weiss, T.; Gutierrez, L. B.; Ulla, M. A.

Comparison of Ni and Ni−Ce/Al2O3 catalysts in granulated and

structured forms: Their possible use in the oxidative dehydrogenation

of ethane reaction. Chem. Eng. J. 2014, 246, 343−352.

(43) Sun, Q.; et al. Studies on the improved thermal stability for

doped ordered mesoporous γ-alumina. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2013,

15, 5670.

(44) Khodakov, A.; Yang, J.; Su, S.; Iglesia, E.; Bell, A. Structure and

properties of vanadium oxide-zirconia catalysts for propane oxidative

dehydrogenation. J. Catal. 1998, 177, 343−351.

(45) Bakare, I. A.; et al. Fluidized bed ODH of ethane to ethylene

over VOx−MoOx/γ-Al2O3 catalyst: Desorption kinetics and catalytic

activity. Chem. Eng. J. 2015, 278, 207−216.

(46) Trovarelli, A. Catalytic Properties of Ceria and CeO 2

-Containing Materials. Catal. Rev. 1996, 38, 439−520.

(47) Reddy, E. P.; Varma, R. S. Preparation, characterization, and

activity of Al2O3-supported V2O5 catalysts. J. Catal. 2004, 221, 93−

101.

(48) Martinezhuerta, M.; et al. Oxidative dehydrogenation of ethane

to ethylene over alumina-supported vanadium oxide catalysts:

Relationship between molecular structures and chemical reactivity.

Catal. Today 2006, 118, 279−287.

(49) Kašpar, J.; Fornasiero, P.; Graziani, M. Use of CeO2-based

oxides in the three-way catalysis. Catal. Today 1999, 50, 285−298.

(50) Koranne, M. M.; Goodwin, J. G.; Marcelin, G. Characterization

of Silica- and Alumina-Supported Vanadia Catalysts Using Temperature Programmed Reduction. J. Catal. 1994, 148, 369−377.

(51) Nakajima, Y.; et al. Ingestion of Hijiki seaweed and risk of

arsenic poisoning. Appl. Organomet. Chem. 2006, 20, 557−564.

(52) Sasikala, R.; Gupta, N. M.; Kulshreshtha, S. K. Temperatureprogrammed reduction and CO oxidation studies over Ce-Sn mixed

oxides. Catal. Letters 2001, 71, 69−73.

(53) Yao, H. Ceria in automotive exhaust catalysts I Oxygen storage.

J. Catal. 1984, 86, 254−265.

(54) Bartholomew, C. H. Fundamentals of industrial toxicology. Food

and Chemical Toxicology; 20, (1982).

(55) Cvetanović, R. J.; Amenomiya, Y. Application of a Temperature-Programmed Desorption Technique to Catalyst Studies. in Adv.

Catal. 1967, 17, 103−149.

(56) Topsoe, N. Infrared and temperature-programmed desorption

study of the acidic properties of ZSM-5-type zeolites. J. Catal. 1981,

70, 41−52.

(57) Chen, W.-H.; et al. A solid-state NMR, FT-IR and TPD study

on acid properties of sulfated and metal-promoted zirconia: Influence

of promoter and sulfation treatment. Catal. Today 2006, 116, 111−

120.

Article

(58) Yan, W.; et al. Improving oxidative dehydrogenation of 1butene to 1,3-butadiene on Al2O3 by Fe2O3 using CO2 as soft

oxidant. Appl. Catal. A Gen. 2015, 508, 61−67.

(59) Datka, J.; Turek, A. M.; Jehng, J. M.; Wachs, I. E. Acidic

properties of supported niobium oxide catalysts: An infrared

spectroscopy investigation. J. Catal. 1992, 135, 186−199.

(60) Wu, Z.; Jin, R.; Liu, Y.; Wang, H. Ceria modified MnOx/TiO2

as a superior catalyst for NO reduction with NH3 at low-temperature.

Catal. Commun. 2008, 9, 2217−2220.

(61) Lee, K. J.; et al. Ceria added Sb-V2O5/TiO2 catalysts for low

temperature NH3 SCR: Physico-chemical properties and catalytic

activity. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2013, 142-143, 705−717.

(62) Cvetanović, R. J.; Amenomiya, Y. A Temperature Programmed

Desorption Technique for Investigation of Practical Catalysts. Catal.

Rev. 1972, 6, 21−48.

(63) Tonetto, G.; Atias, J.; De Lasa, H. FCC catalysts with different

zeolite crystallite sizes: Acidity, structural properties and reactivity.

Appl. Catal. A Gen. 2004, 270, 9−25.

(64) Al-Ghamdi, S.; Volpe, M.; Hossain, M. M.; De Lasa, H. VOx/cAl2O3 catalyst for oxidative dehydrogenation of ethane to ethylene:

Desorption kinetics and catalytic activity. Appl. Catal. A Gen. 2013,

450, 120−130.

(65) Hossain, M. M.; de Lasa, H. I. Reactivity and stability of CoNi/Al2O3 oxygen carrier in multicycle CLC. AIChE J. 2007, 53,

1817−1829.

(66) Owen, O. S.; Kung, M. C.; Kung, H. H. The effect of oxide

structure and cation reduction potential of vanadates on the selective

oxidative dehydrogenation of butane and propane. Catal. Letters 1992,

12, 45−50.

(67) Boullosa-Eiras, S.; Vanhaecke, E.; Zhao, T.; Chen, D.; Holmen,

A. Raman spectroscopy and X-ray diffraction study of the phase

transformation of ZrO2−Al2O3 and CeO2−Al2O3 nanocomposites.

Catal. Today 2011, 166, 10−17.

(68) Francisco, M. S. P.; Mastelaro, V. R.; Nascente, P. A. P.;

Florentino, A. O. Activity and Characterization by XPS, HR-TEM,

Raman Spectroscopy, and BET Surface Area of CuO/CeO2 -TiO2

Catalysts. J. Phys. Chem. B 2001, 105, 10515−10522.

(69) Patel, D.; Andersen, P. J. Oxidative Dehydrogenation of Butane

over Orthovanadates. J. Catal. 1990, 125, 132−142.

(70) Armendariz, H.; et al. Oxidative dehydrogenation of n-butane

on zinc-chromium ferrite catalysts. J. Mol. Catal. 1994, 92, 325−332.

(71) Soler, J.; López Nieto, J. M.; Herguido, J.; Menéndez, M.;

Santamaría, J. Oxidative Dehydrogenation ofn-Butane in a Two-Zone

Fluidized-Bed Reactor. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 1999, 38, 90−97.

(72) Cavani, F.; Ballarini, N.; Cericola, A. Oxidative dehydrogenation of ethane and propane: How far from commercial

implementation? Catal. Today 2007, 127, 113−131.

(73) Lemonidou, A.; Tjatjopoulos, G.; Vasalos, I. Investigations on

the oxidative dehydrogenation of n-butane over VMgO-type catalysts.

Catal. Today 1998, 45, 65−71.

(74) Lee, J. K.; et al. Oxidative dehydrogenation of n-butane over

Mg3(VO4)2/MgO−ZrO2 catalysts: Effect of oxygen capacity and

acidity of the catalysts. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 2012, 18, 1758−1763.

(75) Rubio, O.; Herguido, J.; Menéndez, M.; Grasa, G.; Abanades, J.

C. Oxidative dehydrogenation of butane in an interconnected

fluidized-bed reactor. AIChE J. 2004, 50, 1510−1522.

(76) Dejoz, A.; López Nieto, J. M.; Márquez, F.; Vázquez, M. I. The

role of molybdenum in Mo-doped V−Mg−O catalysts during the

oxidative dehydrogenation of n-butane. Appl. Catal. A Gen. 1999, 180,

83−94.

7421

https://dx.doi.org/10.1021/acs.energyfuels.0c00220

Energy Fuels 2020, 34, 7410−7421