tragic loss in Keats' poetry and Death of a salesman. A*

advertisement

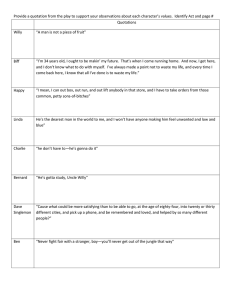

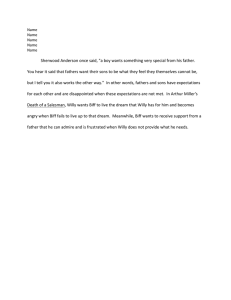

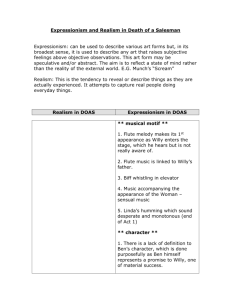

“tragedies typically involve the loss of something that audiences are made to feel is enormously precious”, how far do you agree? I’m really sorry that the essay was too long, its just I struggled to cut down my ideas. I cut a few, but clearly not enough, and then I wanted to at least try to balance the writers to even amounts, as it was very miller heavy. ? However, there are quite a few unproven assertions (so more consistent quotation needed) and your argument is never really clear, it feels at the end that you do not have a straight answer to give. Tragedies involve the feeling of loss and dread as a bad situation spirals out of control. The audience is often presented objects or concepts which get drip-fed to them which they grow attached to, just to lose it, or are shown something lost while giving snippets of when it was still present. Miller in ‘Death of a Salesman’ (DOAS) presents the fractured relationship between Willy and Biff at the forefront. Willy’s wanderings of his mind, where his memories seem to materialise contrast to the strained relationship to an albeit not completely healthy, but a caring relationship between them. Miller himself said that the play “is really a love story between a man and his son”, showing authorial intent for the relationship to be a key element in the story. The tragic loss of something precious is presented as a looming presence over the text, as Willy’s memories present on stage suggest a past relationship where they were on good terms, contrasted with the current one. In the scene where Willy’s mind starts to wander for the first time, Biff has the first line saying, “How’s that, Pop, professional?”, clearly showing that Willy’s mind is wandering back to a time where Biff craved his Father’s approval, as Biff also says “Did you see the new football I got?”, as Biff reveals that he “borrowed” the football, he laughs “confidentially” and Willy “laughs with him” demonstrating to their audience their close bond and how precious it is to lose. In the crucial scene explaining why their current relationship is that way, as he says “you gotta talk to [his teacher] before they close the school. Because if you saw the kind of man you are, and you talked to him in your way, I’m sure he’d come through for me” Other instances of Biff’s admiration to Willy could possibly be down to the memories being In willy’s, possibly exaggerated, mind, and he may be hiding bad elements of the memories (until they emerge by force like Bernard reminding Biff the study for the exam which him not studying ultimately leads to the situation in Boston), but in this scene, Willy is confronting the memory he has been trying to repress, so one can infer that this would be a raw and truthful memory. This makes Biff’s admiration for Willy the most obvious and precious that has ever been seen, and in it, Biff continues to praise willy’s character and skill, not just his attention and praise. This is compared to their current relationship where Willy is torn about his views of his eldest son, calling him a “disgrace”, showing that he is unsure whether or not to believe the divine image of Biff he has in his head, or to believe his opinions on Biff’s lifestyle, however, one may argue that this contradiction is because of Willy’s declining mental capacity, but it may be both, in part, although Willy still deeply cares for Biff and idolises the person he believes him to be as on the stage. Despite there being limited props, “on a shelf over the bed a silver athletic trophy stands”, and as the stage is often seen as the inside of Willy’s mind (Miller previously titled the play “the inside of your head”), it implies that since the bedroom is the most private room of his house, that Willy hold’s Biff and his success to a high degree and treasures it. Biff is also shown to have a negative image of his father as when he is in bed, he mutters “That selfish, stupid…” when he hears his father talking to himself, as well as referring to Willy as a “fake” to his mother showing hostility. Biff also shows that although he has anger and resentment towards Willy, he still cares as after he finds out Willy’s salary was taken away, he calls Willy’s management “ungrateful bastards”. The clear difference “tragedies typically involve the loss of something that audiences are made to feel is enormously precious”, how far do you agree? their past and present relationship looms over the play and in the audience’s heads. The audience is made to feel that the complicated relationship between the two is a loss that is very precious from the visualised memories on stage and the current broken, resentful relationship, as it appears to the audience as a somewhat tragedy of miscommunication. In DOAS another clear instance of loss is monetary. When Willy is first introduced to the audience, he is said to drive a “Studebaker”, but is later reminiscing that he “had that red chevvy”, implying that previously he had a lot more money to spend on a more lavish car. He also says that he had that car in 1928, the year before the wall-street crash, it is implied that Willy continued to work throughout the great depression as Linda says that “[he worked] for a company for thirty-six years” which from 1949 when the play was first performed, it goes beyond the crash, showing that although he continued to work, he would be earning significantly less money, hence the cheaper car. Willy does show that he cares about the car as he remembers Biff polishing/ Simonizing it multiple times “the way Biff used to Simonize that car”, “what a simonizing job”, ”you polish the car so careful”, and as these are happening in Willy’s imaginings that he largely has control over the content of at the beginning of these memories, you can infer that by keeping the car pristine and shiny, it is important to his personal image that he has a gleaming Chevrolet. Willy seems to treasure the car like a trophy of his wealth and success. This is then contrasted to present day, where he has lost his salary (“for five weeks he’s been on straight commission”) and Charley lends him “fifty dollars a week”. This money is contrasted to Willy’s much younger boss Howard, who seems under the illusion that everyone has money and is blissfully ignorant. Howard accidentally flaunts that “only a hundred and a half” is easy money to him, and casually mentioning that Willy should “tell the maid to turn on the radio” and saying “don’t you have a radio in the car?”, seeming genuinely confused that Willy does not have a radio in the car or a maid at his disposal. Although there is a clear loss of money between the imaginings and present day, it is not significantly large as at that time, Willy still never made that much money. He lied to Linda in an imagining and said that he made “five hundred gross in Providence and seven hundred gross in Boston”, when in reality he made “two hundred gross the whole trip” while they had to pay “a hundred and twenty dollars by the fifteenth”. Linda is also seen mending her stockings which were a luxury in Postwar America, suggesting that they can’t afford them. Because the drop in wealth is not that significant as to have caused them to have new debts, it is not that much of a loss. In addition, since Miller was a socialist, he believed that wealth alienates people, like Howard assuming Willy has the money to spend on a new gadget, despite knowing how much he pays him, which turns him into more of a villain. Because of socialism, Miller would have believed that money is not a virtue or a reward for you to lose, rather than the absence of money is a burden to bear. He would not have viewed money as a ‘precious thing to lose’, so it is not presented to the audience as something extremely precious, to be sad to lose, and definitely not comparable to the loss of nature or love. A more subtle instance of loss of something precious in DOAS is the environment and nature surrounding the Lowmans. In the time between the memories taking place and current day, the urban sprawl spread out across America, particularly New York, where the Lowmans live. In the opening stage directions, New York City is described as “towering angular shapes behind it, surrounding it on all sides” which shows an “angry glow of orange”, hinting at the unnatural and aggressive nature of urbanisation and the business world in general. Willy, Biff and somewhat Happy are shown to the audience as admiring nature, which by extension makes in precious to the audience. Willy, “with wonder” says that “it’s so beautiful... the trees are so thick, and the sun is warm… [He] let the warm air bathe over [him]” “tragedies typically involve the loss of something that audiences are made to feel is enormously precious”, how far do you agree? which is a stark contrast to the opening stage directions earlier. The green of the trees and the aggressive orange low are almost contrasting colours, showing the clear juxtaposition to the audience of Willy’s tales in nature and the consuming city. This is a common complaint of Willy’s as he says “the street is lined with cars. There’s not a breath of fresh air in the neighbourhood. The grass don’t grow anymore, you can’t raise a carrot in the backyard. They should’ve had a law against apartment houses. Remember those two beautiful elm trees out there? When I and Biff hung the swing between them?”. When describing nature, he often talks about air in the car in the countryside and now, possibly linking the smoggy air of New York with the crushing sensation stress and exhaustion. Willy clearly yearns for the same outdoor, honest life as Biff, (when all you really desire Is to be outside, with your shirt off”, “there’s nothing more inspiring or- beautiful than the sight of a mare and a new colt”). Miller uses the elm trees to link them Biff and Willy as the two trees were joined together by a swing, and the swing was a bonding moment between the father and son, “Biff…I saw a beautiful hammock. I think I’ll buy it next trip, and we’ll hang it right between those two elms. Wouldn’t that be something? Just swingin’ there under those branches”. Just as willy reaches his lowest point and remembers what happened in Boston and feels a wave of guilt over the affair and the impact on Biff, he rushes to get some seeds (“I’ve got to get some seeds, right away. Nothings planted. I don’t have a thing on the ground.”), showing willy’s association of Nature with success as he wants hard evidence of his achievements of raising something, after his boys left him in the restaurant and he was fired from his job. Willy also associates Ben, and thus success with very rural areas: Alaska and Africa. He even tries to justify living in a city to Ben by saying, “No, Ben, I don’t want you to this… It’s Brooklyn, I know, but we hunt too”. The statement could be said like a desperate plea to Ben and a justification, like living in the Brooklyn is a bad thing, which, in what willy thinks is in Ben’s eyes, is a failure and a sell-out. The guilt makes the situation more tragic to the audience as he seems suffocated by the city, which thus increases the value of the small spots of green and the small chances to breathe amongst the smog. However, it is a more subtle theme so it is not necessarily seen as ‘extremely precious’ as it is not seen that much, so it is not an overbearing sense of loss, like the lost relationship of Biff and Willy, or Lorenzo is Keats’ ‘Isabella’. Attention is lost towards Willy throughout the flashbacks in death of a salesman. Attention is something Willy clearly craves for himself and his boys. One role model he looks up to is Dave Singleman who he idolises because he can work from his room and be “remembered and loved and helped by so many different people”. Supposedly when he died “hundreds of salesman and buyers were at his funeral. Things were sad on a lotta trains for months after that”. This is the reason he went into selling yet, in the present, at work, he is dismissed by Howard. When he wanted to ask his boss for something “Like to ask you a little favour if you…”, yet he gets ignored as Howard is completely fixated on a recording of his daughter which he had presumably heard before. He even tells Willy “sh!” outright dismissing one of his oldest employees with more seniority than him. Once Willy manages to talk about his favour he wants to ask, Howard pushes him aside “starting to go off” and says “I’ve got some people to see kid”. This also happens with ben, another figure he looks up to, as he seems to be constantly “glancing at his watch” and wanting to leave (“raises his hand in farewell” “I’m late for my train” “glancing at his watch”). However, in other imaginings, he tells the boys that he is a beloved salesman“they know me, boys, they know me up and down New England… cause on thing, boys: I have friends. I can park my car in any street in New England, and the cops protect it like their own.” The boys clearly love him and want his around, “Where’d you go this time, dad? Gee we were lonesome for you”, “Gee, id’ love to go with you sometime, Dad”. It is unclear how much of this is genuine, as he does also says the mayor of providence had coffee with him in a hotel lobby, which is very unlikely, but perhaps the “tragedies typically involve the loss of something that audiences are made to feel is enormously precious”, how far do you agree? boys attitudes were genuine, and Willy’s stories were exaggerated to make him seem larger than life for his sons. Attention and familiarity were presented to the audience as extremely precious, at least to Willy, so it is painful to then see him being ignored and deprived of one thing he needs. I think it’s symbolic that the mental illness he has involves memories actualising, meaning he has people to talk to, despite it sometimes being overwhelming as he is talking to imagined and real people at the same time. It happens possibly because it makes Willy feel needed as people optionally come to him, not out of implied obligation, like Ben who visited once, or Biff coming home in between jobs and holidays. Willy is led to being fully ignored, when Happy lies to the girls saying “he’s not my father. He’s just a guy”, when they were encouraging him to go speak to him when he needed his sons the most. He gets “deserted”, and, as Linda says, “his name was never in the paper. He’s not the finest character that ever lived. But he’s a human being, and a terrible thing is happening him. So attention must be paid”, likening money to attention, a surface need of Willy, but presumably, the need for attention runs deep, after being left by his father and his brother. Although Willy never had the level of attention he idolised or expressed that he had, he lost the attention of his sons which hurts the most, especially when the audience has been shown how much it’s needed- making it extremely precious. One thing lost in ‘La Belle Dame sans Merci’ is love between the Knight-at-arms and the mysterious woman. In the cyclical structure, at the start and end of poem, he is said to be “alone2, indicating that the woman is not there, while it is wintertime, as “the sedge has withered” and the “harvest’s done”. The poem that goes back to spring, in the “meads” where flowers were available to make “garlands”. The pathetic fallacy indicates to the reader that while the woman is not in his life, nature id dead and his heart is cold. This is very tied into the romantic movement was nature and love were tied close together. The knight and the woman proceed to fall in love (“she looked at me as if she did love”) in the Knight’s retelling, leading to him “[setting] her on [his] pacing steed”, which is a possible euphemism for sex. The joy of the relationship, and the consistent notes to the warm season (“honey wild, and manna-dew” are seasonal fruits which shows the time jump) contrast with the “cold hill side” he awakes on. This would usually seem like a loss of something precious, love, but it is not that plainly presented to the reader. Her eyes are described as “wild”, suggesting she could not be domesticated to the lifestyle she seems to lead later on when she takes him to her “elfin grot” and feeds him. In addition, the dream the knight has is presented as sinister as “pale kings and princes too, pale warriors, deathpale were they all” indicating her threat. It is heightened by that they all have an honourable position, something the knight has from being a knight, which makes him seem like more of a target. This makes it seem like it was not love that was lost, but the beautiful idea of the woman, that the knight loses. However, I would not say that the woman is really presented as precious, even before the dream, as the heavy handed references to “faerys” indicated something sinister, especially when this was written after Keats went to Scotland and Ireland were there is lots of Gaelic mythology. Knighthood and Chivalry are things lost in Keats’ ‘La Belle Dame sans Merci’. The knight is introduced to the reader as “loitering”, suggesting that he is devoid of purpose and confused, contrasting to the traditional image of the chivalrous ‘knight-at-arms’. He is also described as “haggard and so woe-begone”, but this may not a directly from the loss of purpose. After he meets the ‘lady in the meads’, he “[makes] a garland for her head, and bracelets too, and fragrant zone”, suggesting he is making daisy chains for her. To do this, he would have to remove his armour and chainmail that knights traditionally wear as making flower garlands is fiddly and requires a lot of dexterity and small movements which you can’t usually do in chunky armour. After this, he seems fully enamoured by her “tragedies typically involve the loss of something that audiences are made to feel is enormously precious”, how far do you agree? charms as the next lines are “she looked at me as she did love, and made sweet moan”, which I do not think is a coincidence. She then “found [him] roots of relish sweet, and honey wild, and manna-dew” and “she took [him] to her elfin grot”, showing she has control which is a reversal of the damsel in distress and the knight stereotype. She is giving him food and shelter, therefore is saving him from possible causes of death like starvation, malnutrition, pneumonia etc. The “faery’s child” also tucks him into bed as although he “shut her wild wild eyes with kisses four”, “she lulled [him] asleep”, which visibly tips the power dynamic between them. The loss of knighthood allowed the woman to have the knight rely on her unquestioningly which leads to his tragic ending in the cyclical as he is “palely loitering” without purpose as his life’s meaning of being a knight is taken away. However, this may not be a tragic loss according to Keats as he did not like King George IV, so it is in line for him to suggest that abandoning duty may not be a wholly bad thing, despite the message of the poem. In addition, since he was a romantic poet, Keats was inclined to believe that doing anything for love was correct, even abandoning duty. In keats’ ‘Isabella’, Isabella loses the love of her life, Lorenzo. The audience grows to view their love as enormously precious as Keats gives information on their backstory. They seem to physically need each other as “they could not in the self-same mansion dwell without some stir of heart, some malady; they could not sit at meals but feel how well it soothed each to be the other by”. Although love is seen as a “malady” and a “sick longing” and thus harmful, Keats was a romantic and so viewed young love (their love) as one of the most important things in life. Their story of nervousness and complete fixation on their object of desire can be relatable to the audience. “[she] lispéd tenderly, ‘Lorenzo!’- here she ceased her timid quest, but in her tone and look he read the rest.” Keats perfectly conveys to the reader the tension and anxiety of confessing one’s love, while giving the characters humanising features of Isabel having a lisp and feeling scared but ultimately acting in bravery, and Lorenzo looking physically sick with anxiety as his forehead was “waxing very pale and dead”. Their innocence is meant to be endearing to the reader, especially because of the romanticism movement where youth and instinct are crucial. Keats shows them to the reader as “twin roses by the zephyr blown apart only to meet again more close”. The “zephyr” indicates that their love is very fragile, but they are “twin roses” like they are made for each other and thus very precious and rare. Once Lorenzo goes missing, Keats says “So sweet Isabel by gradual decay from beauty fell/ Because Lorenzo came not”, the enjambment shows how incomplete without her other “twin rose”, as well as it not being a rhyme because it finishes mid-line showing in-completion. It leaves an awkward and alien feeling because she does not have her true love. Isabella then experiences a vision of Lorenzo which informs her about what her brothers did, with lots of references to Greek mythology. Lorenzo is often called a “pale shadow”, “I am a shadow now” which is a reference to Greek Mythology where in the underworld, you were not fully a ghost, only a sub-human/ shade, where you only know that it is better to be alive. The past events are also mentioned to in “while it did unthread the horrid woof of the late darkened time” which is a reference to weaving, and the woof and weft. In mythology, every life is a piece of thread that gets cut once you die, which forms a now ‘darkened’ tapestry, indicating that the horrible murder spreads far beyond one death, but infects other people to the extent that it sullies a part of the tapestry. The references to Greek mythology indicate that their love transcends the mortal realm to Mount Olympus and the underworld, showing to the reader that their love truly is special and should be treasured and protected. Their love is so strong that It was “cold, dead indeed, but not dethroned” in Isabel’s heart and once her lover is gone, she starts to crack. Her nurse, who presumably knew her as a child, acts as a choric character and asks, “what feverous hectic flame burns in thee, child?”, indicating that this is unusual behaviour for her. “tragedies typically involve the loss of something that audiences are made to feel is enormously precious”, how far do you agree? Then, after her basil pot gets taken away from her, she turns into a semi-shadow like Lorenzo. “she looked on dead and senseless things, asking for her lost basil amorously”, her voice is described as “lorn” just like Lorenzo, reminding the reader of the horrible loss they have experienced as something so precious as a fated love is stolen by greed. An implied loss in Keats’ ‘Isabella’, is the loss of wealth. The brothers, en loco parentis, are “enriched from ancestral merchandise” and are repeatedly referred to as both wealthy and selfish, as they are called “money-bags”, “leger-men” and “Hebrews”. They kill Lorenzo out of fear that because Isabella lost her virginity to Lorenzo, they could not “coax her by degrees to some noble and his olive trees”, with olive trees being a lucrative industry, and the pronoun “some”, suggesting that they do not care really who she would marry. But, after they realise that Isabella knows that they murdered Lorenzo, they “left Florence in a moment’s space, never to turn again”, abandoning their work as they owned “mines and factories”, unmoveable assets. They clearly did loose it, but it was never presented as something precious, quite the opposite. Since Keats was left-wing, he would expectedly look down upon hoarders of wealth, who would prioritise economic gains over love. Keats shows the reader that they are selfish and abuse their power. Their workers’ “once proud-quivered loins did melt in blood from stinging whip”, who sent their workers “naked to the hungry shark”. Keats poses the rhetorical question “why were they proud” repeatedly indicating that thy shouldn’t be because they had terrible morals (i.e., murdering someone to get more money despite already being rich), who earnt most their money from being born into “ancestral merchandise”. In conclusion, tragic loss of something extremely precious is customary of tragedies, however, not everything lost is tragic. The term tragic is typically used to indicate something worth monetary value, however, is some tragedies (especially modern ones like ‘Death of a Salesman’), it flips the narrative on its head. In death of salesman, money causes the loss (or better still destruction) of the true precious things: attention, the environment, life, love. In Isabella, money drives Isabella to insanity by extension as Lorenzo was killed for money, leaving her completely alone. I largely agree because the most crucial and clear things that are lost and presented as some of the most important concepts or possessions, although it is often not “something” that is lost, but someone. Death of the person or of the soul is crucial to tragedy, as it provides the high stakes which provide the doom and dread.