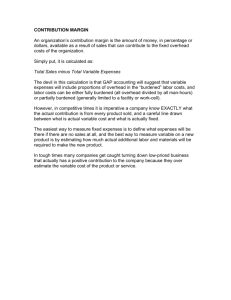

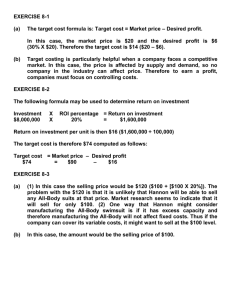

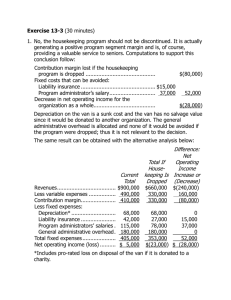

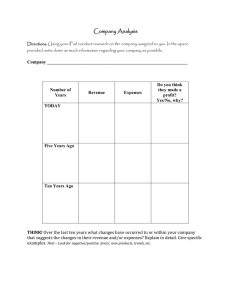

Relevant Costs for Decision Making: Managerial Accounting Chapter

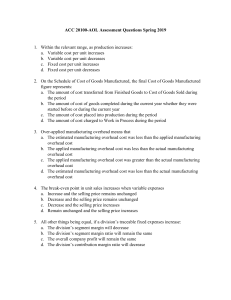

advertisement