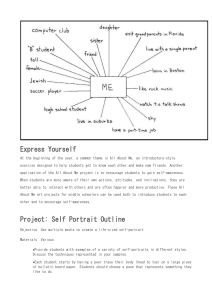

The current issue and full text archive of this journal is available on Emerald Insight at: www.emeraldinsight.com/0262-1711.htm Self-efficacy and self-awareness: moral insights to increased leader effectiveness Cam Caldwell Department of Human Resource Management, Purdue University Northwest, Calumet, Indiana, USA, and Linda A. Hayes Self-efficacy and selfawareness 1163 Received 27 January 2016 Revised 13 June 2016 Accepted 1 July 2016 Department of Management and Marketing, University of Houston – Victoria, Sugar Land, Texas, USA Abstract Purpose – The purpose of this paper is to identify the relationships between self-efficacy and selfawareness and the moral obligations of leaders in understanding and developing these personal qualities. As leaders strive for excellence, self-efficacy and self-awareness can empower them to unlock their own potential and the potential of their organizations and those with whom they work. Design/methodology/approach – The paper integrates research of self-efficacy and self-awareness as they pertain to ethical leadership and presents six propositions that increase leadership effectiveness, create value for the organization, and develop leaders considered my trusted by others. Findings – The authors argue that greater understanding of self-efficacy and self-awareness is important for individual growth and can enable ethical leaders to empower themselves, their colleagues, and the organization in which they work. Research limitations/implications – This research presents six propositions concerning self-efficacy and self-awareness and their influence on effective leadership that can be tested in future research. The ethically based nature of self-efficacy and self-awareness merits additional academic research and practitioner application. Practical implications – This paper provides valuable insights to scholars and practitioners by proposing six propositions that will allow leaders to increase their effectiveness and add value to the organization. Social implications – Ethical leaders add value by continuously improving themselves. Ethical leaders owe it to others and themselves to be more effective through a greater understanding of selfefficacy and self-awareness. Originality/value – Self-efficacy and self-awareness are moral duties associated with the identities of leaders and important for leaders in understanding their own capabilities and identities. Greater knowledge of self-efficacy and self-awareness can enable ethical leaders to be more effective and create value. Keywords Ethics, Self-awareness, Leadership, Self-development, Emotional intelligence, Self-efficacy Paper type Research paper In Aleichem’s enchanting tale, Fiddler on the Roof, the milkman, Tevye, explains that for each person in the village of Anatevka it is vital to understand who he is and without that knowledge, “our lives would be as shaky […] As a fiddler on the roof” (Stein and Bock, 2004, Prologue). In today’s chaotic and constantly evolving world (Cameron, 2003), effective leaders must also know who they are (Covey, 2004) and how to achieve their desired goals (DePree, 2004). As leaders strive to achieve excellence, they recognize that developing self-efficacy and self-awareness can empower them to unlock the potential of their organizations and those with whom they work (Chatterjee, 1998). Journal of Management Development Vol. 35 No. 9, 2016 pp. 1163-1173 © Emerald Group Publishing Limited 0262-1711 DOI 10.1108/JMD-01-2016-0011 JMD 35,9 This paper identifies the relationships between self-efficacy and self-awareness and the moral obligations of leaders in developing these personal qualities. We begin by providing a literature review of the constructs and identify six propositions about leadership effectiveness associated therewith. We conclude by identifying five contributions of this paper to understanding effective leadership. 1164 Review of the literature Although management scholars differ in the nuances of their definitions, we identify integrated definitions of key constructs as they relate to the leader’s responsibilities. Effective leadership requires profound personal insight (Lussier, 2013, pp. 66-71), and leaders owe a complex set of moral duties to themselves and others (Caldwell, 2012). Moral duties of leaders Cameron (2003), Pfeffer (1998), and Kouzes and Posner (2012) are representative of the highly regarded scholars who emphasize that leaders owe moral duties to stakeholders to create long-term wealth and assist employees to achieve their highest potential. DePree (2004, p. 11) described leaders as “servants and debtors” in honoring duties. Paine (2002) emphasized that leaders achieved superior performance only when they merge normative social and instrumental financial imperatives in creating value-based and principle-centered organizations. Other scholars have emphasized the obligation of leaders to be “stewards” who serve others (Hernandez, 2012). Trevino and colleagues (2000) explained that ethical leaders were both “moral persons” and “moral managers” who exemplified virtues while seeking optimal organizational outcomes. Cameron (2011) argued that leaders have the duty to be truly “virtuous” in creating wealth, honoring duties, and adding value. Shao et al. (2008) emphasized that the personal identity and moral identity of leaders must merge to be perceived as trustworthy and authentic. Leaders must balance conflicting ethical perspectives to arrive at a morally sound framework in weighing ethical, legal, and financial consequences (Hosmer, 2010, Ch. 1). Moral leaders do no harm, create value in the short term, and create value in the long term (Lennick and Kiel, 2008). The ability to balance conflicting expectations and complex demands requires that leaders understand who they are, what they value, and the consequences of their actions (Covey, 2004). Identity and moral leadership Identity encompasses that which is central, distinctive, and enduring, and one’s moral choices reflect the way in which (s)he views the self (Caldwell, 2012). For millennia, moral philosophers have encouraged man to pursue the highest good within themselves (Kant and Walker, 2009). Implicit in this pursuit of one’s highest potential is the obligation to constantly review one’s standards and the extent to which one meets them (Stets and Burke, 2014). Those who fail to formally examine and reflect upon their personal values, establish personal standards, and compare those standards with their actions are subject to the common error of self-deception and the erosion of both their own moral identities and the trust in which they are regarded by others (Arbinger Institute, 2010; Burke and Stets, 2009). Those who lead have a duty to make a better world, to improve themselves, to optimize rather than to compromise, and to live life in crescendo rather than in diminuendo (Covey, 2012). A moral leader recognizes that (s)he has the absolute duty to create wealth for society while honoring duties owed to others. The moral leader knows that good is never good enough, and is the enemy of great (Collins, 2001, p. 1). Self-efficacy and the self-concept Self-efficacy refers to one’s belief that (s)he can perform well within the parameters of a specific situation (Bandura, 1995). Fast et al. (2014, p. 1017) defined managerial self-efficacy as “the perceived capacity to be effective and influential within the organizational domain in which one is a manager.” Self-efficacy is a cognitive and affective belief in one’s personal competence and an assessment of one’s ability to confidently act (Pajares, 2002). Judge and Bono (2001) found that self-efficacy was significantly related to successful task performance. One’s self-beliefs allow a person to “apply self-control over who they are, and what they want to be” ( Jayawardena and Gregar, 2013, p. 377). Self-efficacy has a direct positive impact on “the initiation, intensity, and persistence of behavior” (Paglis, 2010, p. 771) Self-efficacy is a key element of a leader’s competence or ability (Mayer et al., 1995), and a leader who lacks an accurate understanding of those competencies puts self and others at risk (Pfeffer, 1998). Smith and Woodworth (2012) explained that a leader’s perceptions of his/her values, duties, and roles are directly related to making a difference in the lives of others. Self-worth and self-efficacy are implicitly connected and impact one’s perceptions about expectations that roles encompass (Burke and Stets, 2009), and affect the choices that individuals make regarding tasks, goals, and roles that they perform (Razek and Coyner, 2014). One’s self-concept evolves as individuals enhance their abilities or recognize that they have previously been operating under false assumptions about competencies (Bandura and Wood, 1989). Lent (2004) explained that life satisfaction increases when individuals feel a sense of personal capability about their goals, when those goals are aligned with their personal values, and when their environment supports goal achievement. Although Bandura (1977, p. 193) originally defined self-efficacy in terms of achieving specific task-related outcomes, Wang and Hsu (2014) reported that self-efficacy was important for both task and role performance. Success in personal accomplishments leads to expectations of successful future outcomes (Fitzgerald and Schutte, 2010, p. 497). Self-efficacy is influenced by beliefs about the degree to which one controls his/her own destiny (Lussier, 2013, p. 31). One’s perceptions about their own personal power affects both their self-esteem and their self-efficacy (Wojciszke and Struzynska-Kujalowicz, 2007). Self-awareness and emotional intelligence Goleman (1995) declared that self-awareness is the keystone of emotional intelligence. Without self-awareness, leaders are unable to demonstrate empathy with others (Richards, 2004). Self-awareness requires “a deep understanding of one’s emotions, as well as one’s strengths and limitations and one’s values and motives” (Goleman et al., 2002, p. 40). Emotional intelligence combines self-awareness with crafting an authentic personal response that demonstrates that one is able to understand others, their needs, and the context of a situation (Goleman, 1995). The degree to which leaders are self-aware enables them to select the most effective responses for working with others (Albrecht, 2009). Church (1997) defined workplace self-awareness in terms of one’s competencies, behaviors, and skills. Self-awareness requires a leader to accurately self-observe (Manz, 2015) and to compare one’s behavior with norms that define oneself (Burke, 1991). Burke and Reitzes (1991) emphasized that one’s view of self correlates with the Self-efficacy and selfawareness 1165 JMD 35,9 1166 commitment in which one engaged in chosen tasks. Social comparison and self-appraisal are the means by which self-awareness occurs (Showry and Manasa, 2014). Goleman (1995) explained that self-awareness involves not only understanding one’s role and relationships but the ability to be authentic in representing oneself and in dealing ethically with others (see Sur and Prasad, 2011). The Stanford University Business Advisory Council identified self-awareness as “the superior competency that leaders must develop” (Showry and Manasa, 2014, p. 16). These definitions frame self-efficacy and self-assessment as moral duties associated with the identities of leaders and the importance of leaders in understanding their own capabilities and identities. Having defined the key constructs of this paper, we now present six propositions. Presenting the propositions As Schmidt and Hunter (2000) explained, a leader’s capability associated with their self-perception lies not only in the ability to solve problems but to continuously learn. This commitment to learning and a focus on application and execution increase a leader’s self-efficacy and are recognized as distinguishing differences between successful and unsuccessful leaders (Rynes et al., 2007). Leaders increase self-efficacy by constantly learning about key elements of their roles – both within their organizations and with customers and competitors outside their organization (Schein, 2010). By looking beyond “conventional wisdom” that is often the cause of organizational dysfunction (Pfeffer, 1998, Ch. 1), leaders develop confidence by increasing their emphasis on evidence-based solutions founded on empirically sound information (Rynes, et al., 2007; Pfeffer and Sutton, 2000). Focusing on evidence-based execution is a critical requirement for successful leaders and organizations (Franken et al., 2009). In a business world where poor decision-making can be disastrous, today’s leader should adopt an approach to making decisions by “translating principles based on best evidence into organizational practice” (Rousseau, 2006, p. 256). Consistent with this discussion of evidence as related to self-efficacy, we offer our first proposition: P1. Leaders who adopt an evidence-based approach to their roles and who constantly learn more about their responsibilities have higher self-efficacy than leaders who do not adopt this approach. Self-efficacy and the increasing of one’s capabilities to lead are enhanced by the process of formally assessing: what one loves to do; one’s strengths or what one does best; what the marketplace will pay for; and what one’s conscience dictates is the best use of one’s time. Covey (2004) explained that the overlapping area of these four critical dimensions constitutes one’s ”voice,” or that unique area in which one should devote his or her efforts to create value for the world. Collins (2001) also identified what one does best, what one loves to do, and what the market will compensate as key elements of organizational success. Knowing where to focus one’s efforts and skills to compete at a world class level enables each one of us to maximize our potential (Collins, 2001). In keeping with this relationship between one’s voice and self-efficacy, we present our second proposition: P2. Leaders who formally assess what they do best, what they love to do, what the marketplace will pay for, and what their conscience then dictates create greater organizational value than leaders who do not conduct such a self-assessment. Self-awareness enables leaders to more fully understand their values and the events that have shaped their lives. Recognizing these factors enables leaders to define how they wish to lead their lives, how they will interact with others, and the standards by which they measure their accomplishments (Covey, 2004). Self-awareness enables individuals to establish an overarching purpose for their lives that serves as an ongoing motivation for their priorities. Authentic leaders strive to become aware of their strengths and limitations, their resources, and the context of their situations (Avolio and Gardner, 2005). With regard to the importance of self-awareness as a duty that leaders owe themselves, we present our third proposition: P3. Leaders who are aware of their own feelings are more effective in dealing with others than leaders who do not recognize the importance of self-awareness. The ability to control one’s responses associated in a specific relationship are key elements of emotional intelligence (Goleman, 1995, 2007) and acknowledges to be an important element of leadership success (Sturm et al., 2014). The desire for control is a universal personality trait associated with self-awareness (Burger, 1992). Although our ability to control is limited within our sphere of influence, we seek to control ourselves and others in an effort to maintain stability and predictability (Viorst, 1998). As an element of emotional intelligence, self-control includes an understanding of: one’s intended objectives; one’s own feelings and responses; the context of a situation and the needs of others; the likely responses of others to one’s individual actions and behaviors; and the degree to which one can regulate his or her response to achieve the desired result (Goleman et al., 2002). Self-awareness requires the integration of responsibility and control in leading oneself (Ross, 2014). Leaders who effectively manage their emotions and impulses and channel them in useful ways demonstrate high empathy for others and use that insight to craft a response that engenders the best possible cooperative relationship (Goleman et al., 2002, pp. 254-255). Monitoring oneself and responding effectively is a refined ability that differentiates emotionally intelligent leaders from others and reflects the degree to which one understands his or her own identity (Mascolo and Fischer, 1998). Our fourth proposition identifies the importance of self-control as a key element of self-awareness and emotional intelligence: P4. Leaders who monitor their own behaviors and actively strive to control their responses are trusted by others more than leaders who do not demonstrate these behaviors. Those who lead are clear about their goals and recognize that they are ineffective if they are not perceived as involved in the pursuit of outcomes that achieve an organization’s purpose while also meeting the needs of others (see Barnard and Andrews, 1971). Self-reflection about why one pursues a course of action also enables individuals to examine their underlying motives and values that drive their actions (Natsoulas, 1998). This increased self-awareness requires comparing one’s personal standard for behavior with one’s actions (Peus et al., 2012). One’s actions are ultimately the consequence of core beliefs and values (Fishbein and Ajzen, 2009), and we constantly evaluate ourselves at the conscious and unconscious levels (Stets and Burke, 2014). By acting consistently with their espoused values, leaders whose behaviors demonstrate integrity earn the followership of others (Schein, 2010). Associated with the nature of self-assessment and how it is formed, we present our fifth proposition: P5. Leaders whose behaviors are consistent with their articulated beliefs, values, and identity standards are perceived as better leaders than those who have not adopted consistent behaviors. Self-efficacy and selfawareness 1167 JMD 35,9 1168 In writing about the importance of seeing oneself as (s)he truly is, Marianne Williamson (1992, pp. 190-191) explained: […] . Our deepest fear is not that we are inadequate. Our deepest fear is that we are powerful beyond measure. It is our light, not our darkness, that most frightens us. We ask ourselves, who am I to be brilliant, gorgeous, talented, fabulous? Actually, who are you not to be? You are a child of God. Your playing small doesn’t serve the world. There’s nothing enlightened about shrinking so that other people won’t feel insecure around you. We are all meant to shine, as children do. We were born to make manifest the glory of God that is within us. It’s not just in some of us; it’s in everyone. And as we let our own light shine, we unconsciously give other people permission to do the same. As we’re liberated from our own fear, our presence automatically liberates others. The ability to view oneself and others as truly great is a key attribute of great leadership (Havard, 2014) and recognizing one’s unlimited individual potential is a fundamental element of self-awareness (see Tsuchiya, 1996). Consistent with these insights, we offer our sixth proposition: P6. Leaders who have high self-awareness have a greater appreciation of their own capabilities than leaders with lower self-awareness. Insights for application Self-efficacy and self-awareness are constructs that define one’s identity, promote selfdevelopment, and enhance “environmental mastery, connection to ideals, and mind and heart-based actions” that are critical to effective leadership (Karp, 2012, p. 128). Effective leaders earn trust by demonstrating personal integrity, high levels of competence, and a commitment to the welfare of others (Dirks and Ferrin, 2002). Enhancing self-awareness and increasing self-efficacy enable leaders to create trustbased relationships and increase their impact in a world desperately seeking leaders (Bennis and Nanus, 2007). Contributions of the paper The importance of leaders examining themselves and assessing their obligation to optimize personal effectiveness are important leadership factors in a world where leaders struggle to be perceived as trustworthy (Maritz Research, 2010). This paper makes five insights for application in examining the moral duties associated with self-efficacy and self-awareness: (1) We focus on duties of self-efficacy and self-awareness as important parts of individual growth, with specific application to the roles of leaders. We affirm that those who lead owe an array of duties which enable them to live more fulfilling and successful lives and be more effective in dealing with others. Understanding the moral and ethical responsibilities of leadership associated with self-efficacy and self-awareness will enable leaders to be more successful in building followership, trust, and commitment. (2) We identify testable propositions about improving leadership effectiveness which can be used by both academic scholars and individual practitioners. We encourage practitioners to reflect on the six propositions and to test them in practical ways in their own organizations. We note that recent research has affirmed that self-awareness and leadership effectiveness can be enhanced by well-structured training and suggest that such training is of great potential value to those who would lead (Gill et al., 2015). We also encourage additional academic research about the nature of self-efficacy and self-awareness. Self-efficacy and selfawareness (3) We emphasize the importance of leaders regularly evaluating their beliefs, values, goals, assumptions, and behaviors which match key elements of their individual identities. Understanding oneself and the core beliefs that frame one’s actions and decisions is a key step for leaders in making integrated decisions and being perceived as trustworthy (Schein, 2010). We encourage leaders to constantly examine the degree to which they are congruent in aligning their behaviors with what they espouse and with their personal identities. 1169 (4) We emphasize the importance of leaders reflecting on and identifying the moral criteria which motivates them as they seek to lead. Leaders who formally conduct such a moral self-assessment are more likely to honor those criteria and lead with greater integrity. By emphasizing the importance of examining their moral standards and understanding their personal motivation to lead, leaders will not only increase their self-awareness but improve their ability to explain the justification for moral decisions (see Hosmer, 2010). (5) We describe leaders as moral stewards and provide added insights about that role and its moral implications. As a stewardship responsibility to create wealth and honor duties owed to stakeholders, leadership imposes obligations that rise to the level of a covenantal responsibility (Pava, 2003). We encourage leaders to reflect on the duties that they owe to others as ethical stewards (Caldwell et al., 2010). Conclusion Like Fiddler on the Roof’s Tevye, leaders who have a clear understanding of who they are will be prepared to deal with the inevitable vicissitudes of life and feel a sense of stability and confidence despite the turmoil that may surround them. Although the focus of leadership and the success of organizations have tended to be based upon cost effectiveness, profitability, and competitive advantage, we join with a growing group of scholars who suggest that normative values in organizations can lead to greater profits than focusing simply on achieving instrumental or financial goals (Collins, 2001; Collins and Porras, 2004; Paine, 2002; Cameron and Spreitzer, 2013). We encourage scholars to empirically test the propositions presented in this paper, but we also encourage practitioners to commit themselves to the self-reflection and assessment suggested herein as well. In a world increasingly struggling to make decisions viewed as quality of life enhancing, wealth creating, and beneficial to mankind, leaders may need to begin with the outside-in approach of self-assessment to understand themselves, their values, and the principles to which they are committed as they fulfill their moral responsibilities (see Covey, 2004). References Albrecht, K. (2009), Social Intelligence: The New Science of Success, Jossey-Bass, San Francisco, CA. Arbinger Institute (2010), Leadership and Self-deception: Getting out of the Box, 2nd ed., Berrett-Koehler Publishers, San Francisco, CA. Avolio, B.J. and Gardner, W.L. (2005), “Authentic leadership development: getting to the root of positive forms of leadership”, Leadership Quarterly, Vol. 16 No. 3, pp. 343-372. JMD 35,9 1170 Bandura, A. (1995), Self-efficacy in Changing Societies, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge. Bandura, A. (1977), “Self-efficacy: toward a unifying theory of behavioral change”, Psychological Review, Vol. 84 No. 2, pp. 191-215. Bandura, A. and Wood, R. (1989), “Effect of perceived controllability and performance standards on self-regulation of complex decision-making”, Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, Vol. 56 No. 5, pp. 805-814. Barnard, C.I. and Andrews, K.R. (1971), The Functions of the Executive: 30th Anniversary Edition, Harvard Business School Press, Boston, MA. Bennis, W. and Nanus, B. (2007), Leaders: Strategies for Taking Charge, 2nd ed., Harper-Collins, New York, NY. Burger, J.M. (1992), “Desire for control and academic performance”, Canadian Journal of Behavioural Science, Vol. 24, April, pp. 147-155. Burke, P.J. (1991), “Identity processes and social stress”, American Sociological Review, Vol. 56 No. 6, pp. 836-849. Burke, P.J. and Reitzes, D.C. (1991), “An identity theory approach to commitment”, Social Psychology Quarterly, Vol. 54 No. 3, pp. 239-251. Burke, P.J. and Stets, J.E. (2009), Identity Theory, Oxford University Press, New York, NY. Caldwell, C. (2012), Moral Leadership: A Transformative Model for Tomorrow’s Leaders, Business Expert Press, New York, NY. Caldwell, C., Hayes, L. and Long, D. (2010), “Leadership, trustworthiness, and ethical stewardship”, Journal of Business Ethics, Vol. 96 No. 4, pp. 497-512. Cameron, K.S. (2003), “Ethics, virtuousness, and constant change”, in Tichy, N.M. and McGill, A.R. (Eds), The Ethical Challenge: How to Lead with Unyielding Integrity, Jossey-Bass, San Francisco, CA, pp. 185-194. Cameron, K.S. (2011), “Responsible leadership as virtuous leadership”, Journal of Business Ethics, Vol. 98 No. 1, pp. 25-35. Cameron, K.S. and Spreitzer, G.M. (Eds) (2013), The Oxford Handbook of Positive Organizational Scholarship, Oxford University Press, Oxford. Chatterjee, D. (1998), Leading Consciously: A Pilgrimage Toward Self-mastery, Routledge, New York, NY. Church, A.H. (1997), “Managerial self-awareness in high-performing individuals in organizations”, Journal of Applied Psychology, Vol. 82 No. 2, pp. 281-292. Collins, J. (2001), Good to Great: Why Some Companies Make the Leap … and Others Don’t, HarperCollins, New York, NY. Collins, J. and Porras, J.I. (2004), Built to last: Successful Habits of Visionary Companies, Harper Business, New York, NY. Covey, S.R. (2004), The 8th Habit: From Effectiveness to Greatness, Free Press, New York, NY. Covey, S.R. (2012), The 3rd Alternative: Solving Life’s Most Difficult Problems, Free Press, New York, NY. DePree, M. (2004), Leadership is an Art, Doubleday, New York, NY. Dirks, K.T. and Ferrin, D.L. (2002), “Trust in leadership: meta-analysis findings and implications for organizational research”, Journal of Applied Psychology, Vol. 87 No. 4, pp. 611-628. Fast, N.J., Burris, E.R. and Bartel, C.A. (2014), “Managing to stay in the dark: managerial selfefficacy, ego defensiveness, and the aversion to employee voice”, Academy of Management Journal, Vol. 57 No. 4, pp. 1014-1034. Fishbein, M. and Ajzen, I. (2009), Predicting and Changing Behavior: The Reasoned Action Approach, Psychology Press, New York, NY. Fitzgerald, S. and Schutte, N.S. (2010), “Increasing transformational leadership through enhancing self-efficacy”, Journal of Management Development, Vol. 29 No. 5, pp. 495-505. Franken, A., Edwards, C. and Lambert, R. (2009), “Executing strategic change: understanding the critical management elements that lead to success”, California Management Review, Vol. 51 No. 3, pp. 49-73. Gill, L., Ramsey, P. and Leberman, S. (2015), “A systems approach to developing emotional intelligence using the self-awareness engine of growth model”, Systemic Practice and Action Research, Vol. 28 No. 6, pp. 575-594. Goleman, D. (1995), Emotional Intelligence: Why It Can Matter more than IQ, Bantam, New York, NY. Goleman, D. (2007), Social Intelligence: The New Science of Human Relationships, Bantam, New York, NY. Goleman, D., Boyatzis, R. and McKee, A. (2002), The New Leaders – Transforming the Art of Leadership into the Science of Results, Time-Warner, London. Havard, A. (2014), Created for Greatness: The Power of Magnanimity, Scepter Publications, New York, NY. Hernandez, M. (2012), “Toward an understanding of the psychology of stewardship”, Academy of Management Review, Vol. 37 No. 2, pp. 172-193. Hosmer, L.T. (2010), The Ethics of Management, 7th ed., McGraw-Hill/Irwin, New York, NY. Jayawardena, C. and Gregar, A. (2013), “Transformational leadership, occupational self-efficacy, and career success of managers”, Proceedings of the European Conference on Management, Leadership, & Governance, pp. 376-383. Judge, T.A. and Bono, J.E. (2001), “Relationship of core self-evaluation traits – self-esteem, generalized self-efficacy, locus of control, and emotional stability – with job satisfaction and job performance: a meta-analysis”, Journal of Applied Psychology, Vol. 86 No. 1, pp. 80-92. Kant, I. and Walker, N. (2009), Critique of Judgment, Oxford University Press, Oxford. Karp, T. (2012), “Developing oneself as a leader”, Journal of Management Development, Vol. 32 No. 1, pp. 127-140. Kouzes, J.M. and Posner, B.Z. (2012), The Leadership Challenge: How to Make Extraordinary things Happen in Organizations, Jossey-Bass, San Francisco, CA. Lennick, D. and Kiel, F. (2008), Moral Intelligence: Enhancing Business Performance and Leadership Success, Wharton School Publishing, Upper Saddle River, NJ. Lent, R.W. (2004), “Toward a unifying theoretical and practical perspective on well-being and psychosocial adjustment”, Journal of Counseling Psychology, Vol. 51 No. 4, pp. 482-509. Lussier, R.N. (2013), Human Relations in Organizations: Applications and Skill Building, 9th ed., McGraw-Hill/Irwin, New York, NY. Manz, C.C. (2015), “Taking the self-leadership high road: smooth surface or potholes ahead”, Academy of Management Perspectives, Vol. 29 No. 1, pp. 132-151. Maritz Research (2010), “Managing in an era of mistrust: Maritz poll reveals employees lack trust in their workplace”, April 14, available at: www.maritz.com/Maritz-Poll/2010/Maritz-PollReveals-Employees-Lack-Trust-in-their-Workplace (accessed January 10, 2016). Mascolo, M.E. and Fischer, K.W. (1998), “The development of self-through the coordination of component systems”, in Ferrari, M. and Sternberg, R.J. (Eds), Self-awareness: Its Nature and Development, The Guilford Press, New York, NY, pp. 332-384. Self-efficacy and selfawareness 1171 JMD 35,9 1172 Mayer, R.C., Davis, J.H. and Schoorman, F.D. (1995), “An integrative model of organizational trust”, Academy of Management Review, Vol. 20 No. 3, pp. 709-734. Natsoulas, T. (1998), “Consciousness and self-awareness”, in Ferrari, M. and Sternberg, R.J. (Eds), Self-Awareness: Its Nature and Development, The Guilford Press, New York, NY, pp. 12-33. Paglis, L.L. (2010), “Leadership self-efficacy: research findings and practical implications”, Journal of Management Development, Vol. 29 No. 9, pp. 771-782. Paine, L.S. (2002), Values Shift: Why Companies must Merge Social and Financial Imperatives to Achieve Superior Performance, McGraw-Hill, New York, NY. Pajares, F. (2002), “Gender and perceived self-efficacy in self-regulated learning”, Theory into Practice, Vol. 41 No. 2, pp. 116-125. Pava, M.L. (2003), Leading with Meaning: Using Covenantal Leadership to Build a Better Organization, Palgrave Macmillan, New York, NY. Peus, C., Wesche, J.S., Streicher, B., Braun, S. and Frey, D. (2012), “Authentic leadership: an empirical test of its antecedents, consequences, and mediating mechanisms”, Journal of Business Ethics, Vol. 107 No. 3, pp. 331-348. Pfeffer, J. (1998), The Human Equation: Building Profits by Putting People First, Harvard Business School Press, Cambridge, MA. Pfeffer, J. and Sutton, R.I. (2000), The Knowing-Doing gap: How Smart Companies Turn Knowledge into Action, Harvard Business School Press, Boston, MA. Razek, N.A. and Coyner, S.C. (2014), “Impact of self-efficacy on Saudi students’ college performance”, Academy of Educational Leadership Journal, Vol. 18 No. 4, pp. 85-96. Richards, D. (2004), The Art of Winning Commitment: 10 Ways Leaders Can Engage Minds, Hearts, and Spirits, ANACOM, New York, NY. Ross, S. (2014), “A conceptual model for understanding the process of self-leadership development and action-steps to promote personal leadership development”, Journal of Management Development, Vol. 33 No. 4, pp. 299-323. Rousseau, D.M. (2006), “Is there such a thing as ‘evidence-based management’?”, Academy of Management Review, Vol. 31 No. 2, pp. 256-266. Rynes, S.L., Giluk, T.L. and Brown, K.G. (2007), “The very separate worlds of academic and practitioner periodicals in human resource management: implications for evidence-based management”, Academy of Management Journal, Vol. 50 No. 5, pp. 987-1008. Schein, E.H. (2010), Organizational Culture and Leadership, 4th ed., Jossey-Bass, San Francisco, CA. Schmidt, F.L. and Hunter, J.E. (2000), “Select on intelligence”, in Locke, E.A. (Ed.), Handbook of Principles of Organizational Behavior, Blackwell, Oxford, pp. 3-14. Shao, R., Aquino, K. and Freeman, D. (2008), “Beyond moral reasoning: a review of moral identity research and its implications for business ethics”, Business Ethics Quarterly, Vol. 18 No. 4, pp. 513-540. Showry, M. and Manasa, K.V.L. (2014), “Self-awareness – key to effective leadership”, IUP Journal of Soft Skills, Vol. 8 No. 1, pp. 15-26. Smith, I.H. and Woodworth, W.P. (2012), “Developing social entrepreneurs and social innovators: a social identity and self-efficacy approach”, Academy of Management Learning & Education, Vol. 11 No. 3, pp. 390-407. Stein, J. and Bock, J. (2004), Fiddler on the Roof: Based on Sholom Aleichem’s Stories, Limelight Editions, New York, NY. Stets, J.E. and Burke, P.J. (2014), “Self-esteem and identities”, Sociological Perspectives, Vol. 67 No. 4, pp. 409-433. Sturm, R.E., Taylor, S.N., Atwater, L.E. and Braddy, P.W. (2014), “Leader self-awareness: an examination and implications of women’s under-prediction”, Journal of Organizational Behavior, Vol. 35 No. 5, pp. 657-677. Sur, V. and Prasad, V. (2011), “Relationship between self-awareness and transformational leadership: a study in IT industry”, IUP Journal of Organizational Behavior, Vol. X No. 1, pp. 7-17. Trevino, L.K., Hartman, L.P. and Brown, M. (2000), “Moral person and moral manager: How executives develop a reputation for ethical leadership”, California Management Review, Vol. 42 No. 4, pp. 128-142. Tsuchiya, T. (1996), “Self-awareness of unlimited potential and its development: the underlying philosophy of the management/staff development programme in Yaohan International Group”, Journal of Management Development, Vol. 15 No. 8, pp. 47-52. Viorst, J. (1998), Necessary Losses: The Loves, Illusions, Dependencies, and Impossible Expectations that All of Us Have to Give up in Order to Grow, Fireside, New York, NY. Wang, S. and Hsu, I.-C. (2014), “The effect of role ambiguity on task performance through self-efficacy-A contingency perspective”, IEEE Transactions on Engineering Management, Vol. 61 No. 4, pp. 681-689. Williamson, M. (1992), A Return to Love, Harper Collins, New York, NY. Wojciszke, B. and Struzynska-Kujalowicz, A. (2007), “Power influences self-esteem”, Social Cognition, Vol. 25 No. 4, pp. 472-494. Further reading Bandura, A. (1997), Self-efficacy: The Exercise of Control, Worth Publishers, New York, NY. Corresponding author Linda A. Hayes can be contacted at: HayesL@uhv.edu For instructions on how to order reprints of this article, please visit our website: www.emeraldgrouppublishing.com/licensing/reprints.htm Or contact us for further details: permissions@emeraldinsight.com Self-efficacy and selfawareness 1173