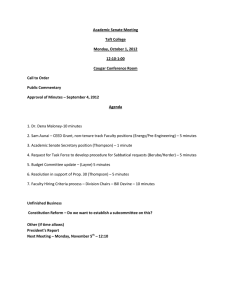

Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, Vol. 14, No. 4, 1995, pp. 325-338 BODY IMAGE AND TELEVISED IMAGES OF THINNESS AND ATTRACTIVENESS: A CONTROLLED LABORATORY INVESTIGATION LESLIE J. HEINBERG Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine J. KEVIN THOMPSON University of South Florida One hundred and thirty-nine women viewed television commercials that con Appearance-related commercials (demonstrating societal ly-endorsed images of thinness and attractiveness) or Non-Appearance-related advertisements. Pre-post measures of depression, anger, anxiety, and body dissatisfaction were examined. Participants were blocked by a median split on dispositional levels of body image disturbance and sociocultural attitudes regarding appearance. Indi viduals high on these measures became significantly more depressed following exposure to the Appearance videotape and significantly less depressed following a viewing of the Non-Appearance advertisements. In addition, individuals high on tained either the level of sociocultural awareness/internalization became more angry and body image disturbance became more dissatisfied with their appearance following exposure to commercials illustrating thinness/attractiveness. Participants who scored below the median on dispositional levels of disturbance either improved or showed no change on dependent measures in both Appearance and Non-Appearance video conditions. The findings are discussed in light of factors that might moderate media-influenced perturbations in body image. participants high on Researchers agree that one of the strongest influences on the develop of body image disturbance is a sociocultural factor (Heinberg, in ment press; Thompson, 1992). A sociocultural model emphasizes that societal standards for attractiveness are often unachievable (Fallon, 1990), but against "unattractive" individuals, a phe "beautyism" by Cash (1990). In contemporary west still lead to discrimination nomenon ern labelled societies, for women, thinness has become almost synonymous with correspondence to J. Kevin Thompson, Ph.D., Department versity of South Florida, Tampa, Florida 33620-8200. Address of Psychology, Uni 325 326 HEINBERG AND THOMPSON & Rodin, 1986; Thompson, 1990). In addition, researchers have found that as thinness is valued, its opposite, obesity, is seriously denigrated (Rodin, Silberstein, & Striegel-Moore, 1985; Spillman & Everington, 1989). beauty (Striegel-Moore, Silberstein, Throughout history, ideals of feminine beauty have varied and changed in accordance with the aesthetic standards of the particular period of time (Ehrenreich & English, 1978; Fallon, 1990; Garner, Gar finkel, Schwartz, & Thompson, 1980; Mazur, 1986). For the last 20-30 years, research suggests that the societal standard of the "ideal" female has been in flux. For example, Garner et al. (1980) examined body reported height America winners from 1960 until 1978 and the pageant waist, and hip and measurements of Miss archival data of measurements of 240 weight Playboy Centerfolds reported bust, over a span of 20 years. After using covariance procedures to control for changes in heights and sizes, they concluded that the weights had decreased signifi cantly. The Playboy data also indicated that bust, waist, and urements have evolved from Interestingly, prevailing female one. a curvaceous Garner et al. standard to hip a more meas tubular (1980) also discovered that while the role models have been getting thinner, average of similar age in the United States have become heavier. similar study, Silverstein, Peterson, and Perdue (1986b) examined women In a changes by measuring body sites of women in photographs Journal and Vogue magazine. A curvaceousness depicted index of the women was computed by taking a bust to waist ratio, in order to control for factors such as height of models and size of picture. Replicating Garner et al. (1980), Silverstein et al. (1986b) also found a trend toward increasing slenderness in women. In another study exam ining sociocultural ideals via magazines, Silverstein, Perdue, Peterson, and Kelly (1986a) examined the occurrence of articles and advertise ments that addressed dietary issues. After examining both men's and women's magazines, they found a female-male ratio of the frequency of occurrence of dietary issues of 159 to 13. In a unique experimental test of the print media influence, Cash, Cash, and Butters (1983) exposed 51 women to pictures of women obtained from magazine ads and articles. Photos were pre-rated for attractiveness level and participants were assigned to three exposure conditions: physi cally attractive, physically attractive/labelled as professional models, and not physically attractive. After viewing the photos, they rated their own level of overall physical attractiveness and body satisfaction. Groups did not differ on body satisfaction (an index of several body sites), however, the participants exposed to the attractive pictorial stim uli rated their own level of physical attractiveness as lower than those who were exposed to the other two conditions (which did not differ from each other). The authors interpreted their findings as supportive of a historical in Ladies Home BODY IMAGE 327 predicted from social comparison theory. only for those individuals exposed to attrac tive peers, rather than photos identified as professional models, Cash et al. (1983) concluded that "peer beauty qualified as a more appropriate standard for social comparison than professional beauty." In a similarly designed study, Irving (1990) had women evaluate slides of models in four conditions: thin, average weight, oversize, and no-ex posure. Using a posttest only design, participants completed measures of self-esteem and body-esteem (weight concern, sexual attractiveness, physical condition) following the manipulation. The results were mixed. negative contrast effect, as Because the effect ocurred The no-exposure group did not differ from other conditions on measures of self-esteem or weight concern, and was lower on sexual attractiveness ratings than the other three groups. However, trend analyses indicated that weight concern increased linearly across exposure group with the highest concern present in the thin condition and lowest in the oversize condition. Across conditions, level of bulimic symptoms was associated with poorer body image on all three measures of the body-esteem scale. Heinberg and Thompson (1992) further tested the relevance of specific comparison targets to body image by asking 297 women and men to rate the importance of six different groups, ranging from particularistic to universalistic (family, friends, classmates, students, celebrities, USA citizens). On similarly, appearance dimension, both producing the following hierarchy of friends classmates > an Thus celebrities are = students given a = celebrities men and women rated comparison importance: > USA citizens weighting equivalent laristic groups of classmates and students, but important than friends. In addition, for women, to are the family. = more particu still rated of as less ratings importance significantly correlated with concurrent levels of body image and eating disturbance. Importantly, the correlations were of the same magnitude as those obtained between classmates/students and indices of body image and eating disturbance. In sum, unlike Cash et al. (1983), Heinberg and Thompson (1992) found evidence for a possible role of media figures (celebrities) as targets that individuals might chose to identify as a relevant comparison group. The role of the broadcast media has also been accorded as having a powerful influence on an individual's body image (Lakoff & Scherr, 1984); however, this sphere of influence has received little empirical analysis. In a recent study, Strauss, Doyle, and Kriepe (1994) examined the effects of television commercials on dietary restraint level. Based on a median split, high restraint and low restraint participants initially received a preload of a "high calorie, nutritionally balanced banana drink" (Strauss et al., 1994). Subsequently, they were given free access to M & Ms and peanuts during the viewing of an excerpt from the movie Terms of Endearment. The movie clip was interrupted by either neutral for celebrities were HEINBERG AND THOMPSON 328 commercials diet-related commercials in two conditions. A third or the movie without any interruption. The results indicated group that participants high in restraint level who viewed the diet commercials saw ate more than those in other conditions. Strauss et al. (1994) established the disinhibiting effect of viewing Interestingly, although a number (Lakoff posit that television may also have a powerful influence on body image, and empirical findings suggest that a negative comparison process may occur in the print medium (Cash et al., 1983; Irving, 1990; Silverstein et al., 1986a,b), researchers have yet to manipulate televised media messages as com parison targets in an effort to determine the effects on body image. Therefore, the present investigation was designed to expose women to societal images of thinness and attractiveness that are communicated through the televised media. This exposure involved viewing a ten minute tape of advertisements that clearly communicated the current dietary commercials of writers on restraint level. & Scherr, 1984; Mazur, 1986) societal ideals of attractiveness. It expected that an intensive exposure to commercials containing reflective of these cultural ideals of attractiveness might elicit was images body image satisfaction and mood than exposure to videotape containing a compilation of non-appearance related ads. Specifically it was hypothesized that dispositional level of negative appearance-related cognitions (an aspect of body image disturbance) would moderate participants' responses to media images of attractive ness, such that only those scoring above the median would experience distress following exposure to appearance-related advertisements. Fur thermore, it was hypothesized that only individuals scoring above the greater changes in a median on a measure would of sociocultural attitudes towards attractiveness experience following exposure to the commercials con of and attractiveness. Finally, subjects exposed thinness taining images a to non-appearance related video stimulus, regardless of dispositional level of disturbance, were not expected to experience significant pertur bations in mood or body image satisfaction. distress METHOD PARTICIPANTS participants were 138 Caucasian female undergraduates attending the University of South Florida (ages 18-48). All participants received extra credit points in exchange for their participation. Seventy-one par ticipants composed the Appearance video group and 67 constituted the Non-Appearance video group. (The decision to narrow the pool to Caucasians was due to two factors: initial randomized assignment left a The 329 BODY IMAGE TABLE 1. Subject Variables: Means and Non (n group Levels = (-value group appearance Variable Significance Appearance 67) (n = 71) (1, 137) Pvalue 21.93 23.77 1.87 .07 129.18 135.73 1.71 .10 Height (in.) 64.75 65.66 0.61 44 Quetlet (wt/ht ) 21.74 22.05 0.16 .69 2.57 2.42 0.54 .59 97.01 97.03 0.01 .99 Age Weight (lbs.) TV viewing (hrs./di*y) Manipulation check (% correct) number of other ethnicities in the neutral group and the video stimulus materials consisted of commercials with primarily disproportionate Caucasian There characters.) were no significant differences found between the two video age, weight, height, level of obesity (Quetelet's Index Wt/Ht ), and average number of hours of daily television viewing. The means, standard deviations, and significance levels of these measures groups are on contained in Table 1. MEASURES Sociocultural Attitudes Towards Appearance Questionnaire (SATAQ; He inberg, Thompson, & Stormer, 1995). The SATAQ is a 14-item, 5-point, Likert-scaled self-report measure that requires individuals to rate state ments (completely agree-completely disagree) that reflect awareness of societal attitudes of thinness and attractiveness (e.g., "Being physically fit is a top priority in today's society") or acceptance of these societal beliefs (e.g., "Photographs of thin women make me wish that I were thin"). Internal consistency (Cronbach's alpha) is .71 for the 6 item Awareness scale and .88 for the 8 item Internalization. The correlation between the two subscales is .34. Cognitive Distortions Scale-Physical Appearance Subscale (BCDSPrange & Gleghorn, 1986). This is a 25-item Likert-scaled self-report measure with an internal consistency (coefficient alpha) of .97. The BCDS-PA measures cognitive distortions related to physical appearance (e.g., My value as a person is related to my weight). Schulman et al. (1986) found similar psychometrics on samples of non-eating disordered controls and individuals with bulimia Bulimia PA; Schulman, Kinder, Powers, nervosa. Visual Analogue Scales created mood (VAS). A number of visual to measure immediate state subsequent to the viewing changes in analogue scales were body satisfaction and of commercials. Because these meas- HEINBERG AND THOMPSON 330 require participants ures to make a slash horizontal line to indicate on a disturbance level, as opposed to responding to a making a numerical rating, it was hoped that the specific question by technique would be (i.e., participants might simply less prone to experimental demand remember previous responses) and thus be more sensitive to a brief constructed: VAS- experimental manipulation. Five measures were Anxiety, VAS-Depression, VAS-Anger, VAS-Body Dissatisfaction, and a VAS-Overall Appearance Dissatisfaction. Participants were instructed to rate how they felt on each of these dimensions by placing a short vertical stroke on a 10 cm millimeter, producing labelled "none" to a "very line. Their responses were scored to the nearest 100-point scale. The range of responses were much." pilot study, the relationship between the VAS measures and more lengthy measures of mood and body image disturbance was determined (N 48). The VAS-depression measure correlated significantly with the Profile of Mood States (POMS)-Depression/ Dejection subscale, r .68, p < .01 (McNair, Lorr & Droppelman, 1971). The VAS-anxiety measure correlated significantly with the POMS-Tension/Anxiety subscale, r .60, p < .01. Additionally, VAS-anger correlated significantly with the POMS- Anger/Hostility subscale, r .53, p < .01. Finally, the VAS-weight In a = = = = dissatisfaction and VAS-overall appearance dissatisfaction both corre lated significantly with the Eating Disorders Inventory-Body Dissatis faction Subscale < .01 and r = (EDI-BD) (Garner, Olmstead, .76, p shared 65% of < .01 respectively. common Because variance, these & Polivy, 1983), r .66, p the two body image VASs = two measures were combined single index of body satisfaction. Although there was a good deal of overlap among the three mood measures, none shared more than 41% into of a common variance, therefore, these measures were treated inde in pendently analyses. Manipulation Checks. In order to ensure that all participants attended to and comprehended the videotape, a five item manipulation check was administered at the end of the experiment. These items consisted of specific questions about the visual stimuli that should have been easily answered. In order to be included in analyses, participants had to answer at least four of the five items correctly (they were not informed that they would be tested in this manner). VIDEOTAPE STIMULI Participants viewed a 10 minute segment containing 20 commercials that approximately 30 seconds in length. In one condition, the Appearance video, commercials contained women who epitomized so- were each 331 BODY IMAGE cietal ideals of thinness and attractiveness. These ads were typically for weight supplements (Slimfast, Weight Watchers), beer, automo biles, fast-food, make-up, and clothing. In contrast, the Non-Appearance loss video was devoid of such messages, and contained advertisements for as pain relievers, household cleaning products, and insur such products ance policies. Both conditions contained advertisements that promi nently featured women, however, the actors were of average or above-average weight and the focus of the advertisement was not on the physical appearance of the individuals in the Non-Appearance condi tion. The commercials videotaped from standard and cable television during day-time and prime-time viewing hours. In the of the development Appearance video compilation, a preliminary 40 commercials were chosen by the experimenters to best reflect media images that emphasized physical appearance (in particular, attractive ness and thinness). The final 10 minute videotape was selected during a in which 42 pilot study undergraduates viewed the advertisements and were carefully interviewed by the experimenter. They were asked what of the stimuli found to be the most powerful in communi aspects they channels were the cating sociocultural standards of thinness and attractiveness. The NonAppearance collection was originally prepared by the experimenters and viewed by nine undergraduates. They were queried about the messages portrayed by the advertisements. None of the nine pilot par ticipants identified issues related to thinness or attractiveness. The actors in the Appearance video were slightly younger than char portrayed in the Non-Appearance video (perhaps selected to represent the societally-endorsed ideal of attractiveness). In addition, there were few Non-Appearance commercials that actually contained actors. These advertisements typically used voice-overs to sell the prod acters ucts. Participants in both conditions viewed the standard color televison set. the study, but were They videotapes on a 13 inch given a specific rationale for if you were watching television in were told to watch "as not your home." PROCEDURE Participants were randomly assigned in groups of 2-8 in the tape sealed envelope, coded to a video condition and viewed small conference They were given a by assigned group. They were first instructed to read and sign two copies of the informed consent, keeping a copy in their possession. The primary experimenter read the instruc tions for completing the packet of measures and encouraged participants a number and room. 332 HEINBERG AND THOMPSON questions regarding the proper completion of the various meas Following the completion of the two dispositional measures, par ticipants completed the visual analogue scales. After the completion of these preliminary measures, the experimenter instructed all participants to return their data packets to the envelope. They were then instructed to view the videotape "as if you were watch ing television in your home." Because there was no break between commercials presented via the videotape, participants were not given the opportunity to interact and contaminate each others reactions to the manipulation. Following the manipulation, participants were asked to take out the last data packet from their envelope, again coded by subject number. This packet contained the visual analogue scales. Following the comple tion of the post measures, the manipulation check was administered. Subsequent to the completion of the manipulation check, experimental points were awarded and a brief verbal description of the purpose of the study was given. Participants were also given information on how to contact the experimenter if they should have any further questions regarding the study. to ask ures. MANIPULATION CHECK All participants successfully conpleted regarding the at least 4 of the 5 items this check, correctly answering content of the experimental or neutral video. DESIGN AND ANALYSES Measures of body image (BCDS-PA) and sociocultural attitudes (SA as independent variables. Although these two scales both measure contructs that are related to body image, they were treated independently in this study. The BCDS-PA assesses appearance-related cognitive distortions, whereas, the SATAQ indexes whether one is (a) aware of societal pressures and/or (b) "buys into" the messages (i.e., accepts and internalizes these pressures, believing it is reasonable to strive to fit the societal stereotype). In addition, although the two scales TAQ) used were positively correlated, the shared common variance is only 23%. Therefore, independent analyses were conducted on the two scales. are A median split was these variables. This is and used to create groups a common procedure high and low in levels of used in research on body disturbance (i.e., restraint, see introduction). For the image BCDS-PA, the median split occurred at a score of 18; for the SATAQ, a eating 333 BODY IMAGE of 55.5 score was used to dichotimize groups into High and Low levels produced the following ns per cell: BCDS-PA Ap of disturbance. This pearance video (High 31; Low 39); Non-Appearance video (High 29; Low 38): SATAQ Appearance video (High 40; Low 31); Non-Appearance video (High 31; Low 36). Time of testing (pre, post) and also served type of video stimulus (Appearance, Non-Appearance) independent variables. VAS measures as variables. A 2 (time of testing) x 2 (video stimulus) dependent x 2 level: (dispositional high, low) MANOVA was conducted across all measures. One MANOVA included BCDS-PA as the third dependent factor and one blocked on overall SATAQ level. (A preliminary analysis as served the individual SATAQ scales revealed a very similar pattern of results, therefore, to reduce the overall number of analyses, the total on SATAQ further score was analyzed used in the final with Fisher's LSD analysis.) Significant post effects were hoc test. RESULTS There significant 3-way interaction for the MANOVA on time, body image disturbance (BCDS-PA), F(4, 127) < An .03. evaluation of the univariates revealed a significant 3-way 2.78, p interaction for the VAS depression, F(l, 130) 9.04, p < .003 and body was a stimulus material, and = = dissatisfaction, F(l, 130) high BCDS-PA women = 4.04, p in the < .05. Post hoc tests revealed that the Appearance condition significantly in creased in depression level from Time 1 to Time 2 (30.8-37.8)) and in body dissatisfaction from Time 1 to Time 2 (55.0-58.5). High BCDS-PA partici pants who viewed the Non-Appearance video significantly decreased in depression from Time 1 (29.1) to Time 2 (24.7) and also significantly decreased in body dissatisfaction level (45.6-40.1). Similarly, low BCDSPA women who viewed either tape significantly decreased in body dissatisfaction from Time 1 to Time 2 pearance: 31.4-28.7). Table 2 contains all analyses. (Non-Appearance: 30.4-28.0; Ap means and standard deviations for The MANOVA with sociocultural awareness/internalization level factor also revealed as significant 3-way interaction, F(4, 127) 3.37, p < .01. Significant univariates emerged for depression level, F(l, 130) 5.23, p < .02, and anger level, F(l, 130) 9.63. p < .002. Post hoc analyses revealed that participants high in sociocultural awareness/internaliza tion level in the Appearance condition increased significantly in depres sion (30.6 36.7) and anger (25.3 29.9). Participants scoring high on this variable who viewed the Non-Appearance tape decreased significantly in level of depression (30.1 27.0) and anger (20.9 16.9). a a = = = 334 HEINBERG AND THOMPSON TABLE 2. Means, Standard Deviations, and Significance Levels for Three-Way Interactions Time 1 Variable Neutral Time 2 Experimental Experimental Neutral Depression (26.3)a (28.7) 30.8 (24.3) 24.7 (28.6)a 37.8 Low BCDS-PA 17.7(16.0) 19.6 (17.7) 18.2 (17.0) 18.7(19.2) High SATAQ 30.1 (28.0) 30.6 (24.8) 27.0 (28.4)a 36.7 (26.5)a Low SATAQ 16.1 (15.0) 18.7 (16.4) 15.9 (15.3) 17.1 (17.8) High SATAQ 20.9 (24.6) 25.3(21.1) 16.9 (21.5)a 29.9 (26.0)a Low 11.8(16.0) 13.8 (17.7) 12.8 (15.6) 10.5 (13.0)a BCDS-PA 45.6 55.0 (21.0) 40.1 (24.2)a 30.4 31.4(23.4) 28.0 (26.7)a (24.4)a 58.5 Low BCDS-PA 28.7 (22.9)a High BCDS-PA 29.1 Anger SATAQ Body Dissatisfaction High Significant changes (25.2) (22.7) from Time 1 to Time 2. Standard deviations are in parentheses. DISCUSSION These findings suggest that media-presented images of thinness and attractiveness may negatively affect mood and body satisfaction. The findings also support a moderating effect of dispositional level of distur bance only participants in the Appearance video condition with high image disturbance and sociocultural awareness/internalization increased in distress following exposure. Women who scored above the median in dispositional level of disturbance exposed to the Non-Appearance video improved in mood and body satisfaction. Partici pants below the median in level of dispositional disturbance in both Appearance and Non-Appearance video conditions either improved or showed no change on the dependent variables. The influence of the Appearance video on women with high levels of dispositional disturbance is of special importance. Although this limits the generalizability of the results, it indicates that, for certain individuals, levels of body the media-communicated messages of thinness and attractiveness are especially salient. It is critical to further examine these individuals in future research. Perhaps they are more sensitive to media-communi they use this high profile group as a social comparison target (Heinberg & Thompson, 1992). The correspondence between laboratory induced changes in body image and mood found in this study replicates earlier findings when participants consumed foodstuffs (Thompson, Coovert, Pasman, & Robb, 1993). The parallel changes in measures of mood (depression level) cated messages because 335 BODY IMAGE and body satisfaction indicate that the effect is not specific to body image, question of whether the findings reflect a more global shift in negative self-evaluation. Within the current design it is impossible to determine whether the two measures body image and mood change independently or synergistically. Cash (1994) has theorized that contex tual events (similar to the video exposure provided in this study) prime and raises the processing of self-evalu appearance" (p. 1169). For individuals at the activation lead to negative self-evaluation of appear high-risk, may in in reflected ance, changes body image ratings. Such cognitive processing approaches to body image have received a great deal of recent attention in the body image literature (e.g., Altabe & Thompson, in press; LaBarge, Cash, & Brown, in press) and provide a plausible explanation for the findings in the current investigation. Per pre-existing "schematic, investment-driven ative information about one's haps the videotape primed appearance evaluative schema, which led participants to compare themselves to the models portrayed in the advertisements, which led to negative feelings about their own body, which led to an overall dysphoric reaction. We are currently evaluating one aspect of this model, by manipulating level of appearance compari son via a direct comparison vs. distraction experimental condition. It is important to note that the findings in the current investigation are limited to the specific advertisements selected for the two conditions and the Caucasian female sample evaluated. As noted earlier, the actors were predominately Caucasian, emphasizing prototypes of thinness and at tractiveness found in these specific types of commercials. It is possible that these standards may differ in advertisements which contain indi viduals of another ethnic background. In addition, body image concerns may not manifest primarily as a desire for thinness in non-Caucasian women (Altabe, press). Therefore, future extensions of this paradigm need to carefully evaluate prevailing societal media messages and spe cific body image concerns as a function of ethnicity. In addition, this same concern is relevant for any investigation of men or individuals of different ages (i.e., adolescents, elderly). In this study, no effort was made to select advertisements that featured only celebrities. Only 2-3 commercials featured well-known personali ties. As noted earlier, Heinberg and Thompson (1992) found similar importance ratings for the targets of celebrities, classmates, and other students. However, Cash et al. (1983) found that self ratings of attractive ness were lower for participants who compared to attractive peers, than those who were exposed to "not attractive" peers and attractive celebri ties. Irving (1990) did not test the peer vs. celebrity issue, using only slides of models taken from fashion magazines and catalogs. Future research might further examine the effects of exposure to a variety of in 336 HEINBERG AND THOMPSON different comparison targets by creating specific each type of reference group. Participants most at-risk for negative high pre-existing a video conditions for reaction to media messages body image distur "buy societally-presented images (as measured by the SATAQ). Interestingly, Irving (1990) blocked individu appear to be those with bance als on or individuals who bulimic levels of into" symptoms, but found no interaction between level of disturbance and exposure condition (thin, average, oversize, no-expo sure). The lack of an interaction in this study, as opposed to the current investigation, might be attributed to the difference in blocking measures (bulimic symptoms vs. body image/sociocultural endorsement). Our blocking measures may have been more sensitive to individuals vulner able to media messages than Irving's (1990) more global measure of eating disturbance. Thus, the appearance-related video stimuli in our study may have been more directly relevant to the concerns of partici pants dichotomized specifically by their level of physical appearance-re lated cognitions and awareness/internalization of societal standards regarding appearance. In addition, even though level of bulimic symp tomatology is associated with body dissatisfaction (Thompson, 1990), we have found a shared variance of only 13% (Scalf-Mclver & the same measure of bulimic symptoms as Thompson, 1989), using Irving (1990). Another potential explanation for the differences between Irving (1990) and the current study may lie in the selection of dependent measures and the research design. The visual analogue scales used in our were chosen study specifically to be state indices of disturbance, sensitive to immediate changes in status. Irving's (1990) body image measure the body-esteem scale taps into a more traitlike aspect of body image (Thompson, 1992, in press). In addition, as noted earlier, Irving (1990) used a posttest only design any presence of a priori group differences may have contributed to the lack of an interaction between bulimic level and exposure condition. Clearly, however, our findings illustrative of a dispositional influence on women's reaction to video- presented images need replication. Studies in the future should work to refine the current experiment. For important to discern which aspect of media messages is the most powerful or distressing to those at risk. Is it possible to disen tangle varying effects due to diet advertisements, commercials focusing on beauty, or images focusing on thinness? A comparison among these various messages may generate important confirmatory evidence for sociocultural theories of disturbance. Projected research should also vary the instructional protocol given to participants prior to the videotape. For example, they could be instructed to "compare yourself," "focus on example, it is BODY IMAGE 337 your body," or alternatively, to "try to disregard images." By altering the instructions, evidence may be found for cognitive strategies facilitative for rejecting societal messages. Future research should also examine how individuals effectively beauty. Perhaps these individuals differ in their body image-related cognitive schemas (Strauman & Glenberg, 1994). How do these individuals cognitively challenge the messages communicated by the media? And, more importantly, can these challenging skills be effectively taught to individuals with initially higher levels of body image disturbance? If clinical samples and/or persons with high levels of body image disturbance differ from relatively asymptomatic persons on schemas, comparison targets and/or cogni tive distortions, perhaps these individuals can be taught skills and strategies to lessen their distress when confronted with the omnipresent societal messages that women must be attractive to be accepted. disregard some societal standards for thinness and REFERENCES Altabe, M.N. (in press). Body image and ethnicity. In J.K. Thompson (Ed.), Body image, eating disorders, and obesity: An integration guide for assessment and treatment. Wash ington, D.C.: American Psychological Association. Altabe, M. N., & Thompson, J. K. (in press). Body image: A cognitive self-schema? Cognitive Therapy and Research. Cash, T. F. (1990). The psychology of physical appearance: Aesthetics, attributes, and images. In T. F. Cash and T. Pruzinsky (Eds.), Body images: Development, deviance, and change. New York: Guilford. Cash, T. F. (1994). Body image attitudes: Evaluation, investment, and affect. Perceptual and Motor Skills, 78, 1168-1170. Cash, T. F Cash, D. W., & Butters, J. W. (1983). "Mirror, mirror, effects and self- evaluations of ogy, 9, 359-364. Ehrenreich, B., & English, D. (1978). For her own good: 150 years New York: Anchor on the wall..?": Contrast physical attractiveness. Personality and Social Psychol of the experts' advice to women. Press/Doubleday. Fallon, A.E. (1990). Culture in the mirror: Sociocultural determinants of body image. In T.F. Cash and T. Pruzinsky (Eds.), Body Images: Development deviance, and change. New , York: Guilford. Garner, D. M., Garfinkel, P. E., Schwartz, D., & Thompson, M. (1980). Cultural expectations of thinness in women. Psychological Reports, 47, 483-491. Garner, D. M., Olmstead, P., & Polivy, J. (1983). Development and validation of mensional eating disorder inventory for anorexia nervosa a multidi and bulimia. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 2, 15-34. Heinberg, L. J. (in press). Theories of body image disturbance. In J. K. Thompson (Ed.), Body image, eating disorders, and obesity: An integrative guide for assessment and treat ment. Washington, D.C.: American Psychological Association. Heinberg, L. J., & Thompson, J. K. (1992). Social comparison: Gender, target importance ratings, and relation to body image disturbance. Journal of Social Behavior and Personality, 7, 335-344. 338 HEINBERG AND THOMPSON L. J., Thompson, J. K., & Stormer, S. (1995). Sociocultural Attitudes Towards Appearance Scale (SATAQ). International Journal of Eating Disorders, 17, 81-89. Irving, L. M. (1990) Mirror images: Effects of the standard of beauty on the self- and body-esteem of women exhibiting varying levels of bulimic symptoms. Journal of Heinberg, Social and Clinical LaBarge, A. Psychology, 9, 230-242. S., Cash, T. F., & Brown, T. A. (in press). Use of examine appearance-schematic information processing Stroop task to Cognitive modified a in college women. and Research. Therapy Lakoff, R. T., & Scherr, R. L. (1984). Face value: The politics of beauty. Routledge & Kegan Paul. Mazur, A. (1986). U.S. trends in feminine beauty and overadaptation. The Journal Research, 22, 281-303. of Sex Profile of Mood States. McNair, D., Lorr, M., San Diego, & Droppleman, L. (1971). EDITS manuals for CA: Education and Industrial Testing the Service. Rodin, J., Silberstein, L. R., & Striegal-Moore, R. H. (1985). Women and weight: A normative discontent. In T.B. Sonderegger (Ed.), Psychology and gender, Nebraska Symposium on Motivation, 1984. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press. Scalf-Mclver, L., & Thompson, J. K. (1989). Family correlates of bulimic characteristics in college Schulman, R. females. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 45, 467-472. G., Kinder, B. N., Powers, P. S., Prange, M., & Glenhorn, A. (1986). The development of a scale to measure cognitive distortions in bulimia. Journal of Personality Assessment, 50, 630-639. Silverstein, B., Perdue, L., Peterson, B., & Kelly, E. (1986a). The role of the mass media in promoting a thin standard of bodily attractiveness for women. Sex Roles, 1 4, 519-532. Silverstein, B., Peterson, B., & Perdue, L. (1986b). Some correlates of the thin standard of bodily attractiveness for women. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 5, 895-905. Spillman, D. M., & Everington, C. (1989). Somatotype revisited: Have the media changed perception of the female body image? Psychological Reports, 64, 887-890. Glenberg, A.M. (1994). Self-concept and body image distrubance: which self-beliefs predict body size overestimation? Cognitive Therapy and Research, 8, our Strauman, T.J., & 105-125. Doyle, A.E. & Kreipe, R.E. (1994). The paradoxical effect of diet commercials on dietary restraint. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 103, 441-444. Striegel-Mooore, R. H., McAvay, G., & Rodin, J. (1986). Psychological and behavioral correlates of feeling fat in women. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 5, 935-947. Striegel-Moore, R., Silberstein, L. R., & Rodin, J. (1986). Toward an understanding of risk factors for bulimia. American Psychologist, 41, 246-263. Thompson, J. K. (1990). Body image disturbance: Assessment and treatment. Elmsford, N.Y.: Strauss, J., reinhibition of Pergaman. Thompson, J.K. (1992). Body image: extent of disturbance, associated features, theoretical models, assessment methodologies, intervention strategies, and a proposal for a new DSM IV diagnostic category body image disorder. In M. Hersen, R. M. Eisler, and P. M. Miller (Eds.), Progress in behavior modification category (pp. 3-54). Sycamore, IL: Sycamore Publishing, Inc. Thompson, J. K. (in press). Body image, eating disorders, and obesity: An integrative guide for assessment and treatment. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. Thompson, J. K., Coovert, D. L., Pasman, L. N., & Robb, J. (1993). Body image and food consumption: Three laboratory studies of perceived caloric content. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 14, 445-457.