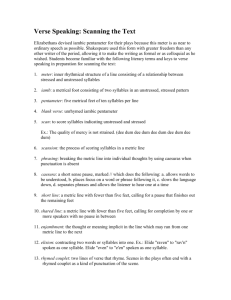

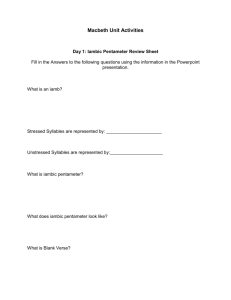

This document is designed as a resource for teachers which can be adapted to use with your students. Shakespeare's Language Introduction In Shakespeare's words lie all the clues to character and situation that any reader or actor needs. It's simply a matter of knowing how to find them. The clues are not necessarily in the meanings of the words - the rhythms of the language and the patterns and sounds of the words contain a great deal of valuable information. Here are some suggestions for finding the clues in Shakespeare's language: Blank verse Both written and spoken language use rhythm - a pattern of stressed and unstressed syllables. Most forms of poetry or verse take rhythm one step further and regularise the rhythm into a formal pattern of stressed and unstressed syllables. A formal pattern of rhythm is called metre. Shakespeare writes either in blank verse, in rhymed verse or in prose. Blank verse is unrhymed but uses a regular pattern of rhythm or metre. In the English language, blank verse is iambic pentameter. Pentameter means there are five poetic feet. In iambic pentameter each of these five feet is composed of two syllables: the first unstressed; the second stressed. The opening line of Twelfth Night, is a perfect iambic line : 'If music be the food of love play on' With its unstressed and stressed syllables marked or 'scanned', it looks like this: ں/ ں/ ں/ 'If mu sic be the food = ںweak ں/ ں/ of love play on' / = strong The rhythm of blank verse is conversational and with its dee DUM, dee DUM, dee DUM, dee DUM, dee DUM rhythm, it imitates the heartbeat. In conversation, we often break the rhythmic pattern and this throws specific words into focus. Shakespeare does the same with blank verse: he often deviates from the perfect iambic line. When he does, it's a clue to a change in the character's feelings or thoughts or a change in situation or both. When the rhythm is changed, the energy and dynamic of the language have been changed. Feel how abrupt, uneven and ragged the rhythm is in the final scenes of Macbeth – here, Macbeth's last hope is dashed and Birnam Wood is seen to move to Dunsinane: MACBETH ں / ں/ ں/ ں/ ں/ Throw physic to the dogs; I'll none of it. / / ں / ں/ ں/ ں/ Come, put mine armour on; give me my staff. / ں ں / / ں ں / ں/ ں Seyton, send out. Doctor, the thanes fly from me. / / ں/ Come, sir, dispatch. Page 1 © RSC King Lear's anguished protest against the murder of Cordelia (and perhaps of the Fool as well) reverses the rhythmic order of the syllables as Lear's world itself has been incomprehensibly upended: KING LEAR / ں/ ں/ ں/ ں/ ں Never, never, never, never, never. In addition to the repetition of 'never,' the emphasis on the first syllables of each foot suggests a blocking, a refusal to accept the unacceptable. The unstressed syllable ending each foot communicates a sense of hopelessness. When the line ends in an unstressed syllable rather than a stressed one, as is usual with iambic pentameter, this is sometimes called a feminine or weak ending. Several lines ending in unstressed syllables in a speech call for investigation on the part of the reader. Consider the opening lines of Othello's speech to the Venetian Senate: OTHELLO ں / ں / ں / ں / ں Most potent, grave and reverend signiors, ں/ ں/ ں/ ں/ ں / ں My very noble and approved good masters, ں/ ں / ں/ ں/ ں / ں That I have ta'en away this old man's daughter, ں/ ں / ں/ ں / ں / It is most true; true I have married her. ں/ ں/ ں / ں/ ں/ ں The very head and front of my offending ں / ں/ ں/ Hath this extent, no more... What accounts for this series of weak endings? Is Othello feeling defensive in putting his case to the senators? Or is he, with irony, subtly undermining their power and status? Or is there another reason? This is an actor's choice, but a choice that will have vital implications for characterisation. Just as an actor will 'beat through' the verse (for example, by clapping), when looking for clues to his character's state of being, so students of Shakespeare can benefit from beating out the rhythms of the verse and considering what might explain deviations from the iambic line. Rhymed verse While blank verse forms the basis of Shakespeare's writing, he often uses rhyme. Frequently a rhymed couplet (a pair of lines whose end words rhyme) closes the scene and sometimes suggests what will come next: HAMLET The play's the thing Wherein I'll catch the conscience of the King. Shakespeare uses rhyme and a variety of rhythm patterns to distinguish special characters such as the witches in Macbeth and Puck in A Midsummer Night's Dream. 'Double, double, toil and trouble / Fire burn and cauldron bubble,' chant the witches . In addition to the rhyme, notice that this is not an iambic line, being only four feet long and with the stresses reversed from the iambic. Shakespeare has created a special musical rhythm for these supernatural characters. Page 2 © RSC Shakespeare’s Famous Last Words CLARENCE Which of you, if you were a prince's son, Being pent from liberty, as I am now, if two such murderers as yourselves came to you, Would not entreat for life? My friend, I spy some pity in thy looks: O, if thine eye be not a flatterer, Come thou on my side, and entreat for me, As you would beg, were you in my distress A begging prince what beggar pities not? —Richard III YOUNG SIWARD Thou liest, abhorred tyrant; with my sword I'll prove the lie thou speak’st. —MacBeth Son He has kill'd me, mother: Run away, I pray you! —MacBeth OTHELLO I kiss'd thee ere I kill'd thee: no way but this; Killing myself, to die upon a kiss. —Othello HOTSPUR O, Harry, thou hast robb'd me of my youth! I better brook the loss of brittle life Than those proud titles thou hast won of me; They wound my thoughts worse than sword my flesh: But thought's the slave of life, and life time's fool; And time, that takes survey of all the world, Must have a stop. O, I could prophesy, But that the earthy and cold hand of death Lies on my tongue: no, Percy, thou art dust And food for— —Henry IV Part 1 EMILIA Moor, she was chaste; she loved thee, cruel Moor; So come my soul to bliss, as I speak true; So speaking as I think, I die, I die. —Othello HASTINGS O bloody Richard! miserable England! I prophesy the fearful'st time to thee That ever wretched age hath look'd upon. Come, lead me to the block; bear him my head. They smile at me that shortly shall be dead. —Richard III First Servant O, I am slain! My lord, you have one eye left To see some mischief on him. O! —King Lear CORNWALL I have received a hurt: follow me, lady. Turn out that eyeless villain; throw this slave Upon the dunghill. Regan, I bleed apace: Untimely comes this hurt: give me your arm. —King Lear OSWALD O, untimely death! —King Lear TYBALT Thou, wretched boy, that didst consort him here, Shalt with him hence. —Romeo and Juliet REGAN My sickness grows upon me —King Lear GONERIL Ask me not what I know. —King Lear CLAUDIUS O, yet defend me, friends; I am but hurt. —Hamlet