A Decade of Development Aid in Indonesia after Reformasi - Hoelman, Mickael B, Tifa Foundation, 2012

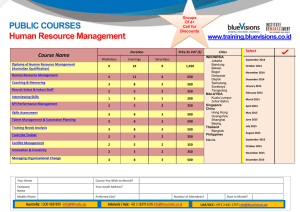

advertisement