CHAPTER 17

Exchange rates and the open

economy

LEARNING OBJECTIVES (LO)

After reading this chapter, you should be able to answer the following questions.

17.1 What is a nominal exchange rate?

a) How is the nominal exchange rate related to the trade weighted index?

17.2 What is the difference between fixed and floating exchange rates?

Copyright © 2019. McGraw-Hill Education (Australia) Pty Limited. All rights reserved.

17.3 What is the difference between a nominal and a real exchange rate?

17.4 What assumptions underlie the purchasing power parity theory of exchange rates?

a) Given purchasing power parity, what should happen to a country’s exchange rate if its inflation rate is

higher than that of its neighbours?

b) Outline the limitations of the purchasing power parity theory of exchange rates.

17.5 What factors determine the supply of dollars/demand for dollars in the international currency market?

17.6 Under a flexible exchange rate:

a) What is the significance of the equilibrium value of the currency?

b) How does monetary policy impact on the exchange rate?

17.7 Under a fixed exchange rate:

a) What is meant by a speculative attack on a currency?

b) How effective is monetary policy?

17.8 What factors influence a country’s choice of fixed or flexible exchange rates?

Bernanke, B., Olekalns, N., & Frank, R. (2019). Principles of macroeconomics. ProQuest Ebook Central <a onclick=window.open('http://ebookcentral.proquest.com','_blank')

href='http://ebookcentral.proquest.com' target='_blank' style='cursor: pointer;'>http://ebookcentral.proquest.com</a>

Created from usyd on 2021-06-23 12:42:18.

ole24015_ch17_431-464.indd

431

02/26/19 07:58 PM

432

PART 4 OPEN-ECONOMY MACROECONOMICS

Copyright © 2019. McGraw-Hill Education (Australia) Pty Limited. All rights reserved.

SET TING THE SCENE

In earlier chapters, we outlined the challenges faced by

policymakers dealing with high rates of inflation. Bringing the

rate of inflation down can be a difficult task and requires a very

disciplined approach to macroeconomic policy, particularly

monetary policy. Moreover, as discussed in Chapter 12,

policy credibility is an important component of an anti-inflation

monetary policy. Unless the central bank is believed to be

serious about running the required tight monetary policy,

attempts to bring the rate of inflation down are unlikely to

succeed.

One way that some countries have used to ensure policy

credibility is through exchange rate policies. Consider the case

of Argentina. In 1989, Argentina’s rate of inflation was 5000

per cent and the inefficiencies associated with this high rate

of inflation were contributing to real gross domestic product

(GDP) falling. Excessive growth in the money supply was held

responsible for the high inflation rate. In response, what became

known as the ‘convertibility plan’ was introduced in April 1991.

Under this plan, an Argentinian peso became convertible into

one US dollar, no matter what the circumstances. To make this

work, Argentina’s Central Bank committed to holding one US

dollar for every peso that was in circulation.

This is an example of a fixed exchange rate system. By

guaranteeing that one peso would always convert into one US

dollar, Argentina committed to an exchange rate with respect

to the United States that was always 1:1. With this system

in place, the freedom to run an independent monetary policy,

or to use the Central Bank’s ability to print money to finance

a budget deficit (which had previously been an often-used

practice in Argentina) was removed. Monetary policy was

severely restricted, being directed to maintain the parity with

LO 17.1, 17.2

nominal exchange rate

The rate at which two

currencies can be traded

for each other.

the US dollar. The hope was that the monetary discipline this

imposed would enable a credible anti-inflation policy to be

implemented.

The results were, initially, as hoped. Inflation fell to single

digits by 1994 and real GDP began to grow. However, by the

end of 2001, the convertibility plan was abandoned, and

Argentina defaulted on its debt to the rest of the world.

What went wrong? One factor was a strengthening of the

US dollar over the second half of the 1990s. As Argentina had

tied its currency to the US dollar, this meant the peso also

strengthened. As you will see in this chapter, a consequence

of this is to make domestic goods less competitive in world

markets, reducing the demand for exports, and at the same

time, enabling easier purchases of imports—both reduce

aggregate demand. To make matters worse, Argentina’s

government continued to be quite profligate with its fiscal

policy, borrowing heavily on international capital markets to

cover its large budget deficits.

A worsening in economic performance led to the

abandonment of the convertibility system, thus allowing the

peso to weaken as a way of boosting exports and discouraging

imports. However, as much of the debt had been borrowed in

US dollars, the effect of allowing the peso to weaken was to

massively increase the burden of debt repayments—a great

many more pesos were needed to repay the debt. Rather

than risk the reoccurrence of high inflation if the pesos were

provided by the Central Bank, the Argentinian Government took

the dramatic step of defaulting, that is, not honouring its debts.

Argentina’s experience shows the key role exchange

rate arrangements can have in affecting macroeconomic

performance. This is a theme we explore in this chapter.

17.1 NOMINAL EXCHANGE RATES

As explained in Chapter 16, trade between nations in goods and services permits greater specialisation and efficiency

brought about by shifting resources into productive activities in which a nation has a comparative advantage. However,

trade between nations usually involves dealing in different currencies, a reality we did not consider in Chapter 16.

So, for example, if an Australian resident wants to purchase a car manufactured in the Republic of Korea, they (or,

more likely, the car dealer) must first trade dollars for the Korean currency, the won. The Korean car manufacturer

is then paid in won. Similarly, an Argentine who wants to purchase shares in an Australian company (an Australian

financial asset) must first trade their Argentinian pesos for dollars and then use the dollars to purchase the shares.

Because international transactions generally require that one currency be traded for another, the relative

values of different currencies are an important factor in international economic relations. The rate at which two

currencies can be traded for each other is called the nominal exchange rate, or more simply the exchange rate,

between the two currencies. For example, if one Australian dollar can be exchanged for 200 Japanese yen, the

nominal exchange rate between the Australian and Japanese currencies is 200 yen per dollar. Each country has

Bernanke, B., Olekalns, N., & Frank, R. (2019). Principles of macroeconomics. ProQuest Ebook Central <a onclick=window.open('http://ebookcentral.proquest.com','_blank')

href='http://ebookcentral.proquest.com' target='_blank' style='cursor: pointer;'>http://ebookcentral.proquest.com</a>

Created from usyd on 2021-06-23 12:42:18.

ole24015_ch17_431-464.indd

432

02/26/19 07:58 PM

Exchange rates and the open economy CHAPTER 17

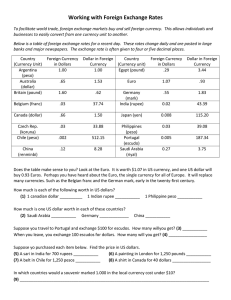

Table 17.1 Nominal exchange rates for the Australian dollar (4pm, 14 November 2018)

FOREIGN CURRENCY PER

AUSTRALIAN $

United States dollar

0.7217

1.3856

Chinese renminbi

5.0164

0.1993

Japanese yen

82.22

European euro

0.6394

South Korean won

818.83

0.0122

1.5640

0.0012

Singapore dollar

0.9959

1.0041

New Zealand dollar

1.0656

0.9384

UK pound sterling

0.5558

1.7992

Malaysian ringgit

3.0239

0.3307

Thai baht

23.76

Indonesian rupiah

10652

0.0421

0.0001

Indian rupee

52.07

0.0192

New Taiwan dollar

22.29

0.0449

Vietnamese dong

Copyright © 2019. McGraw-Hill Education (Australia) Pty Limited. All rights reserved.

AUSTRALIAN $ PER UNIT OF

FOREIGN CURRENCY

16819

0.0001

Hong Kong dollar

5.6524

0.1769

Papua New Guinea kina

2.43

0.4115

Swiss franc

0.727

1.3755

United Arab Emirates dir

2.6504

0.3773

Canadian dollar

0.9559

1.0461

Trade-weighted Index

62.7

0.0159

Source: ©Reserve Bank of Australia 2018, ‘Exchange rates’, https://www.rba.gov.au/statistics/frequency/exchange-rates.html.

All rights reserved.

many nominal exchange rates, one corresponding to each currency against which its own currency is traded.

Thus the Australian dollar’s value can be quoted in terms of US dollars, English pounds, Swedish krona, Israeli

shekels, Russian rubles or dozens of other currencies. Table 17.1 gives exchange rates between the Australian

dollar and selected currencies as at 4 pm on 14 November 2018.

As Table 17.1 shows, exchange rates can be expressed either as the amount of foreign currency needed to purchase

one dollar (left column) or as the number of dollars needed to purchase one unit of the foreign currency (right column).

These two ways of expressing the exchange rate are equivalent: each is the reciprocal of the other. For example, at 4 pm

on 14 November 2018, the Australian–US dollar exchange rate could have been expressed either as 0.7217 US dollars

per Australian dollar or as 1.3856 Australian dollars per US dollar, where 0.7217 = 1/1.3856.

EXAMPLE 17.1 – NOMINAL EXCHANGE RATES

Based on Table 17.1, find the exchange rate between the UK and US currencies. Express the

exchange rate in both US dollars per pound and pounds per US dollar.

continued

Bernanke, B., Olekalns, N., & Frank, R. (2019). Principles of macroeconomics. ProQuest Ebook Central <a onclick=window.open('http://ebookcentral.proquest.com','_blank')

href='http://ebookcentral.proquest.com' target='_blank' style='cursor: pointer;'>http://ebookcentral.proquest.com</a>

Created from usyd on 2021-06-23 12:42:18.

ole24015_ch17_431-464.indd

433

02/26/19 07:58 PM

433

434

PART 4 OPEN-ECONOMY MACROECONOMICS

Example 17.1 continued

From Table 17.1 we see that 0.5558 UK pounds will buy an Australian dollar, and that 0.7217 US

dollars will buy an Australian dollar. Therefore 0.5558 UK pounds and 0.7217 US dollars are equal in

value:

0.5558 UK pounds = 0.7217 US dollars

Dividing both sides of this equation by 0.7217, we get:

0.7701 UK pounds = 1 US dollar

In other words, the United Kingdom–United States exchange rate can be expressed as 0.7701 UK

pounds per US dollar. Alternatively, the exchange rate can be expressed as 1/0.7701 = 1.2984 US

dollars per pound.

CONCEPT CHECK 17.1

Copyright © 2019. McGraw-Hill Education (Australia) Pty Limited. All rights reserved.

From the business section of the newspaper or an online source (try the Reserve Bank of Australia’s website at www.rba.gov.au),

find recent quotations of the value of the Australian dollar against the British pound, the Singapore dollar and the Japanese yen.

Based on these data, find the exchange rate:

a) between the pound and the Singapore dollar

b) between the Singapore dollar and the yen.

Express the exchange rates you derive in two ways (e.g. both as pounds per Singapore dollar and as Singapore dollars per pound).

appreciation

An increase in the value of

a currency relative to other

currencies.

depreciation

A decrease in the value of

a currency relative to other

currencies.

In this chapter we will use the symbol e to stand for a country’s nominal exchange rate. Although the exchange

rate can be expressed either as foreign currency units per unit of domestic currency, or vice versa, as we saw in

Table 17.1, let us agree to define e as the number of units of the foreign currency that the domestic currency will buy.

For example, if we treat Australia as the ‘home’ or ‘domestic’ country and Japan as the ‘foreign’ country, e will

be defined as the number of Japanese yen that one dollar will buy. Defining the nominal exchange rate this way

implies that an increase in e corresponds to an appreciation, or a strengthening, of the home currency, while a

decrease in e implies a depreciation, or weakening, of the home currency.

Figure 17.1 shows the nominal exchange rate for the Australian dollar for the period from 12 December

1983 to14 November 2018. Rather than showing the value of the dollar relative to that of an individual foreign

currency, such as the Japanese yen or the British pound, the figure expresses the value of the dollar as an average

of its values against other major currencies. This is known as the trade weighted index since countries with which

Australia does a lot of international trade are given a relatively higher weight in the calculation of the index than

countries with which Australia does little trade.

The choice of beginning date for this graph is very significant. On that day the Australian dollar was floated.

This meant that, from that day, market forces became the main determinant of Australia’s exchange rate.

Prior to that date the Reserve Bank of Australia intervened on a regular basis in foreign exchange markets

to influence the value of the dollar. We will discuss these issues in more detail later in the next section of

the chapter.

You can see from Figure 17.1 that, since its float, the dollar’s value has fluctuated over time, sometimes

decreasing (as in the period 1983 to 1986), sometimes increasing (as in 2003–04) and sometimes changing quite

dramatically (as in the second half of 2008 during the Global Financial Crisis). An increase in the value of a

currency relative to other currencies is known as an appreciation; a decline in the value of a currency relative to

other currencies is called a depreciation. So we can say that the dollar depreciated in 1983–86 and appreciated

in 2003–04. We will discuss the reasons a currency may appreciate or depreciate later in this chapter.

Bernanke, B., Olekalns, N., & Frank, R. (2019). Principles of macroeconomics. ProQuest Ebook Central <a onclick=window.open('http://ebookcentral.proquest.com','_blank')

href='http://ebookcentral.proquest.com' target='_blank' style='cursor: pointer;'>http://ebookcentral.proquest.com</a>

Created from usyd on 2021-06-23 12:42:18.

ole24015_ch17_431-464.indd

434

02/26/19 07:58 PM

Exchange rates and the open economy CHAPTER 17

Trade weighted index (May 1970 = 100.0)

95

85

75

65

55

45

12

/

12 12

/ /1

12 12 98

/ /1 3

12 12 98

/ /1 4

12 12 98

/ /1 5

12 12 98

/ /1 6

12 12 98

/ /1 7

12 12 98

/ /1 8

12 12 98

/ /1 9

12 12 99

/ /1 0

12 12 99

/ /1 1

12 12 99

/ /1 2

12 12 99

/1 /1 3

12 2 99

/ /1 4

12 12 99

/ /1 5

12 12 99

/ /1 6

12 12 99

/ /1 7

12 12 99

/ /1 8

12 12 99

/ /2 9

12 12 00

/ /2 0

12 12 00

/ /2 1

12 12 00

/ /2 2

12 12 00

/ /2 3

12 12 00

/ /2 4

12 12 00

/ /2 5

12 12 00

/ /2 6

12 12 00

/ /2 7

12 12 00

/ /2 8

12 12 00

/ /2 9

12 12 01

/ /2 0

12 12 01

/ /2 1

12 12 01

/ /2 2

12 12 01

/ /2 3

12 12 01

/ /2 4

12 12 01

/1 /2 5

2/ 01

20 6

17

35

Year

Figure 17.1 Australia’s trade weighted nominal exchange rate

Note: The trade weighted exchange rate is an index of Australia’s exchange rates with all of its trading partner countries. Those

countries with which Australia does a lot of trade receive a relatively higher weight in the calculation of the index.

Copyright © 2019. McGraw-Hill Education (Australia) Pty Limited. All rights reserved.

Source: Based on Reserve Bank of Australia 2018, ‘Historical data’, https://www.rba.gov.au/statistics/historical-data.html#exchange-rates.

17.1.1 FLEXIBLE VERSUS FIXED EXCHANGE RATES

As we saw in Figure 17.1, the exchange rate between the Australian dollar and other currencies is not constant

but varies continually. Indeed, changes in the value of the dollar occur daily, hourly, even minute by minute.

Such fluctuations in the value of a currency are normal for countries like Australia, which have a flexible or

floating exchange rate. The value of a flexible exchange rate is not officially fixed but varies according to

the supply and demand for the currency in the foreign exchange market—the market on which currencies of

various nations are traded for one another. We will discuss the factors that determine the supply and demand

for currencies shortly.

Some countries do not allow their currency values to vary with market conditions but instead maintain a

fixed exchange rate. The value of a fixed exchange rate is set by official government policy. (A government that

establishes a fixed exchange rate typically determines the exchange rate’s value independently, but sometimes

exchange rates are set according to an agreement among a number of governments.) Some countries or regions

fix their exchange rates in terms of the US dollar (e.g. Hong Kong) but there are other possibilities. Some

French-speaking African countries have traditionally fixed the value of their currencies in terms of the French

franc. Under the gold standard, which many countries used until its collapse during the Great Depression,

currency values were fixed in terms of ounces of gold. In the next section we will focus on flexible exchange

rates but we will return later to the case of fixed rates. We will also discuss the costs and benefits of each type of

exchange rate system.

flexible exchange rate

An exchange rate whose

value is not officially fixed,

but varies according to the

supply and demand for

the currency in the foreign

exchange market.

foreign exchange market

The market on which

currencies of various

nations are traded for one

another.

fixed exchange rate

An exchange rate whose

value is set by official

government policy.

Bernanke, B., Olekalns, N., & Frank, R. (2019). Principles of macroeconomics. ProQuest Ebook Central <a onclick=window.open('http://ebookcentral.proquest.com','_blank')

href='http://ebookcentral.proquest.com' target='_blank' style='cursor: pointer;'>http://ebookcentral.proquest.com</a>

Created from usyd on 2021-06-23 12:42:18.

ole24015_ch17_431-464.indd

435

02/26/19 07:58 PM

435

436

PART 4 OPEN-ECONOMY MACROECONOMICS

⊳⊳ RECAP

The nominal exchange rate is the price of one currency in terms of another currency. The trade weighted

exchange rate is an average of one country’s exchange rates with all of its trading partners, where relatively

important trading partners are accorded a relatively larger weight. If the nominal exchange rate is defined

as the amount of foreign currency required to purchase one unit of domestic currency, an increase in the

numerical value of the exchange rate is an appreciation, while a decrease in the numerical value of the

exchange rate is a depreciation.

Exchange rates can be either flexible or fixed. In a flexible exchange rate system, the supply and demand

for a nation’s currency determines the value of the exchange rate. In a fixed exchange rate, interventions

in the internal currency market by the government or central bank are used to influence the level of the

exchange rate.

LO 17.3

17.2 THE REAL EXCHANGE RATE

Copyright © 2019. McGraw-Hill Education (Australia) Pty Limited. All rights reserved.

The nominal exchange rate tells us the price of the domestic currency in terms of a foreign currency. As we will

see in this section, the real exchange rate tells us the price of the average domestic good or service in terms of the

average foreign good or service. We will also see that a country’s real exchange rate has important implications for

its ability to sell its exports abroad and to purchase imports from other countries.

To provide background for discussing the real exchange rate, imagine you are in charge of purchasing for a

company that is planning to acquire a large number of new computers. The company’s computer specialist has

identified two models, one Japanese-made and one Australian-made, that meet the necessary specifications.

Since the two models are essentially equivalent, the company will buy the one with the lower price. However,

since the computers are priced in the currencies of the countries of manufacture, the price comparison is not so

straightforward. Your mission is to determine which of the two models is cheaper.

To complete your assignment you will need two pieces of information: the nominal exchange rate between the

dollar and the yen, and the prices of the two models in terms of the currencies of their countries of manufacture.

Example 17.2 shows how you can use this information to determine which model is cheaper.

EXAMPLE 17.2 – COMPARING PRICES EXPRESSED IN DIFFERENT CURRENCIES

An Australian-made computer costs $2400 and a similar Japanese-made computer costs

242 000 yen. If the nominal exchange rate is 110 yen per dollar, which computer is the better buy?

To make this price comparison we must measure the prices of both computers in terms of the

same currency. To make the comparison in dollars, we first convert the Japanese computer’s price

into dollars. The price in terms of Japanese yen is ¥242 000 (the symbol ¥ means ‘yen’), and we are

told that ¥110 = $1. To find the dollar price of the computer, then, we observe that for any good or

service:

Price in yen = price in dollars × value of dollar in terms of yen

Note that the value of a dollar in terms of yen is just the yen–dollar exchange rate. Making this

substitution and solving, we get:

Price in yen

Price in dollars = _____________________

= __________

242 000 = 2200

Yen : dollar exchange rate

110

Our conclusion is that the Japanese computer is cheaper than the Australian computer at $2200,

or $200 less than the price of the Australian computer, $2400. The Japanese computer is the

better deal.

Bernanke, B., Olekalns, N., & Frank, R. (2019). Principles of macroeconomics. ProQuest Ebook Central <a onclick=window.open('http://ebookcentral.proquest.com','_blank')

href='http://ebookcentral.proquest.com' target='_blank' style='cursor: pointer;'>http://ebookcentral.proquest.com</a>

Created from usyd on 2021-06-23 12:42:18.

ole24015_ch17_431-464.indd

436

02/26/19 07:58 PM

Exchange rates and the open economy CHAPTER 17

CONCEPT CHECK 17.2

Continuing Example 17.2, compare the prices of the Japanese and Australian computers by expressing both prices in terms of yen.

Copyright © 2019. McGraw-Hill Education (Australia) Pty Limited. All rights reserved.

In Example 17.2 the fact that the Japanese computer was cheaper implied that your firm would choose it over

the Australian-made computer. In general, a country’s ability to compete in international markets depends in

part on the prices of its goods and services relative to the prices of foreign goods and services, when the prices

are measured in a common currency. In the hypothetical example of the Japanese and Australian computers,

the price of the domestic (Australian) good relative to the price of the foreign (Japanese) good is $2400/$2200,

or 1.09. So the Australian computer is 9 per cent more expensive than the Japanese computer, putting the

Australian product at a competitive disadvantage.

More generally, economists ask whether on average the goods and services produced by a particular country

are expensive relative to the goods and services produced by other countries. This question can be answered by

the country’s real exchange rate. Specifically, a country’s real exchange rate is the price of the average domestic

good or service relative to the price of the average foreign good or service, when prices are expressed in terms of

a common currency.

To obtain an equation for the real exchange rate, recall that e equals the nominal exchange rate (the number

of units of foreign currency per dollar) and that P equals the domestic price level, as measured, for example,

by the consumer price index. We will use P as a measure of the price of the ‘average’ domestic good or service.

Similarly, let P f equal the foreign price level. We will use P f as the measure of the price of the ‘average’ foreign

good or service.

The real exchange rate equals the price of the average domestic good or service relative to the price of the

average foreign good or service. It would not be correct, however, to define the real exchange rate as the ratio

P/P f because the two price levels are expressed in different currencies. As we saw in Example 17.2, to convert

foreign prices into dollars we must divide the foreign price by the exchange rate. By this rule, the price in dollars

of the average foreign good or service equals P f/e. Now we can write the real exchange rate as:

real exchange rate

The price of the average

domestic good or service

relative to the price of the

average foreign good or

service, when prices are

expressed in terms of a

common currency.

Price of domestic good

Real exchange rate = ________________________

= __

Pf

Price of foreign good in dollars __

Pe

To simplify this expression, multiply the numerator and denominator by e to get:

Real exchange rate = ___

ePf

P

Equation 17.1

which is the equation for the real exchange rate.

To check this equation let us use it to re-solve the computer example, Example 17.2. (For this exercise we

imagine that computers are the only good produced by Australia and Japan, so the real exchange rate becomes

just the price of Australian computers relative to Japanese computers.) In that example the nominal exchange

rate, e, was ¥110/$1, the domestic price, P (of a computer), was $2400 and the foreign price, P f, was ¥242 000.

Applying Equation 17.1, we get:

(¥110 / $1) × 2400

Real exchange rate for computers = _______________

¥242 000

________

= ¥264 000

¥242 000

= 1.09

which is the same answer we derived earlier.

Bernanke, B., Olekalns, N., & Frank, R. (2019). Principles of macroeconomics. ProQuest Ebook Central <a onclick=window.open('http://ebookcentral.proquest.com','_blank')

href='http://ebookcentral.proquest.com' target='_blank' style='cursor: pointer;'>http://ebookcentral.proquest.com</a>

Created from usyd on 2021-06-23 12:42:18.

ole24015_ch17_431-464.indd

437

02/26/19 07:58 PM

437

438

PART 4 OPEN-ECONOMY MACROECONOMICS

The real exchange rate, an overall measure of the price of domestic goods relative to foreign goods, is an important

economic variable. As Example 17.2 suggests, when the real exchange rate is high, domestic goods are on average

more expensive than foreign goods (when priced in the same currency). A high real exchange rate implies that

domestic producers will have difficulty exporting to other countries (domestic goods will be ‘overpriced’), while

foreign goods will sell well in the home country (because imported goods are cheap relative to goods produced

at home). Since a high real exchange rate tends to reduce exports and increase imports, we conclude that net

exports will tend to be low when the real exchange rate is high, all else being equal. Conversely, if the real exchange

rate is low then the home country will find it easier to export (because its goods are priced below those of foreign

competitors), while domestic residents will buy fewer imports (because imports are expensive relative to domestic

goods). Thus net exports will tend to be high when the real exchange rate is low, all else being equal.

Equation 17.1 also shows that the real exchange rate tends to move in the same direction as the nominal

exchange rate, e (since e appears in the numerator of the equation for the real exchange rate). This is especially

the case over relatively short periods of time when average price levels in the respective economies are likely to

change very little, if at all. To the extent that real and nominal exchange rates move in the same direction, we can

conclude that net exports will be hurt by a high nominal exchange rate and helped by a low nominal exchange rate.

Copyright © 2019. McGraw-Hill Education (Australia) Pty Limited. All rights reserved.

THINKING AS AN ECONOMIST 17.1

Does a strong currency imply a strong economy?

Politicians and the public sometimes take pride in the fact that their national currency is ‘strong’, meaning

that its value in terms of other currencies is high or rising. Likewise, policymakers sometimes view a

depreciating (‘weak’) currency as a sign of economic failure. Does a strong currency necessarily imply a

strong economy?

Contrary to popular impression, there is no simple connection between the strength of a country’s

currency and the strength of its economy. For example, Figure 17.1 shows that the value of the Australian

dollar relative to other major currencies was greater in the year 1983 than in the year 2004, though

Australia’s economic performance was considerably better in 2004 than in 1983, a period of recession

and high inflation.

One reason a strong currency does not necessarily imply a strong economy is that an appreciating

currency (an increase in e) tends to raise the real exchange rate (equal to eP/Pf), which may hurt a

country’s net exports. For example, if the dollar strengthens against the yen (i.e. if a dollar buys more yen

than before), Japanese goods will become cheaper in terms of dollars. The result may be that Australians

prefer to buy Japanese goods rather than goods produced at home. Likewise, a stronger dollar implies

that each yen buys fewer dollars, so exported Australian goods become more expensive to Japanese

consumers. As Australian goods become more expensive in terms of yen, the willingness of Japanese

consumers to buy Australian exports declines. A strong dollar may therefore imply lower sales and profits

for Australian industries that export, as well as for Australian industries (like car manufacturers) that

compete with foreign firms for the domestic Australian market.

REVIEW

The real exchange rate is the price of the average domestic good or service relative to the price of the average

foreign good or service, when prices are expressed in terms of a common currency. A formula for the real exchange

rate is eP/P f, where e is the nominal exchange rate, P is the domestic price level and P f is the foreign price level.

An increase in the real exchange rate implies that domestic goods are becoming more expensive relative

to foreign goods, which tends to reduce exports and stimulate imports. Conversely, a decline in the real

exchange rate tends to increase net exports.

Bernanke, B., Olekalns, N., & Frank, R. (2019). Principles of macroeconomics. ProQuest Ebook Central <a onclick=window.open('http://ebookcentral.proquest.com','_blank')

href='http://ebookcentral.proquest.com' target='_blank' style='cursor: pointer;'>http://ebookcentral.proquest.com</a>

Created from usyd on 2021-06-23 12:42:18.

ole24015_ch17_431-464.indd

438

03/06/19 07:58 AM

Exchange rates and the open economy CHAPTER 17

LO 17.4

17.3 THE DETERMINATION OF THE EXCHANGE RATE

Countries that have flexible exchange rates, such as Australia and New Zealand, see the international values

of their currencies change continually. What determines the value of the nominal exchange rate at any point in

time? In this section we will try to answer this basic economic question. Again, our focus for the moment is on

flexible exchange rates, whose values are determined by the foreign exchange market. Later in the chapter we

discuss the case of fixed exchange rates.

17.3.1 A SIMPLE THEORY OF EXCHANGE RATES: PURCHASING POWER PARITY

The most basic theory of how nominal exchange rates are determined is called purchasing power parity, or PPP. To

understand this theory we must first discuss a fundamental economic concept, called the law of one price. The law

of one price states that if transport costs are relatively small, the price of an internationally traded commodity must

be the same in all locations. For example, if transport costs are not too large, the price of a bushel of wheat ought to

be the same in Mumbai and Sydney. Suppose that were not the case—that the price of wheat in Sydney was only half

the price in Mumbai. In that case, grain merchants would have a strong incentive to buy wheat in Sydney and ship it

to Mumbai, where it could be sold at double the price of purchase. As wheat left Sydney, reducing the local supply,

the price of wheat in Sydney would rise, while the inflow of wheat into Mumbai would reduce the price in Mumbai.

If the law of one price were to hold for all goods and services (which is not a realistic assumption, as we will

see shortly), then the value of the nominal exchange rate would be determined, as Example 17.3 illustrates.

law of one price

If transport costs are

relatively small, the price

of an internationally traded

commodity must be the

same in all locations.

EXAMPLE 17.3 – HOW MANY INDIAN RUPEES EQUAL ONE AUSTRALIAN DOLLAR?

Suppose that a bushel of grain costs 5 Australian dollars in Sydney and 150 rupees in Mumbai. If the

law of one price holds for grain, what is the nominal exchange rate between Australia and India?

Because the market value of a bushel of grain must be the same in both locations, we know that

the Australian price of wheat must equal the Indian price of wheat, so that:

Copyright © 2019. McGraw-Hill Education (Australia) Pty Limited. All rights reserved.

5 Australian dollars = 150 Indian rupees

Dividing by 5, we get:

1 Australian dollar = 30 Indian rupees

Thus the nominal exchange rate between Australia and India should be 30 rupees per Australian dollar.

CONCEPT CHECK 17.3

The price of gold is $US300 per ounce in New York and 2500 Swedish krona per ounce in Stockholm. If the law of one price holds for

gold, what is the nominal exchange rate between the US dollar and the Swedish krona?

Example 17.3 and Concept Check 17.3 illustrate the application of the purchasing power parity theory.

According to the purchasing power parity (PPP) theory, nominal exchange rates are determined as necessary

for the law of one price to hold.

A particularly useful prediction of the PPP theory is that, in the long run, the currencies of countries that

experience significant inflation will tend to depreciate. To see why, we will extend the analysis in Example 17.4.

EXAMPLE 17.4 – HOW MANY INDIAN RUPEES EQUAL ONE AUSTRALIAN DOLLAR?

purchasing power parity

(PPP)

The theory that nominal

exchange rates are

determined as necessary

for the law of one price

to hold.

Suppose India experiences significant inflation, so that the price of a bushel of grain in Mumbai

rises from 150 to 300 rupees. Australia has no inflation, so the price of grain in Sydney remains

continued

Bernanke, B., Olekalns, N., & Frank, R. (2019). Principles of macroeconomics. ProQuest Ebook Central <a onclick=window.open('http://ebookcentral.proquest.com','_blank')

href='http://ebookcentral.proquest.com' target='_blank' style='cursor: pointer;'>http://ebookcentral.proquest.com</a>

Created from usyd on 2021-06-23 12:42:18.

ole24015_ch17_431-464.indd

439

02/26/19 07:58 PM

439

440

PART 4 OPEN-ECONOMY MACROECONOMICS

Example 17.4 continued

unchanged at 5 Australian dollars. If the law of one price holds for grain, what will happen to the

nominal exchange rate between Australia and India?

As in Example 17.3, we know that the market value of a bushel of grain must be the same in both

locations. Therefore:

5 Australian dollars = 300 rupees

Equivalently:

1 Australian dollar = 60 rupees

The nominal exchange rate is now 60 rupees per Australian dollar. Before India’s inflation the

nominal exchange rate was 30 rupees per Australian dollar (Example 17.3). So in this example,

inflation has caused the rupee to depreciate against the Australian dollar. Conversely, Australia, with

no inflation, has seen its currency appreciate against the rupee.

The link between inflation and depreciation makes economic sense. Inflation implies that a

nation’s currency is losing purchasing power in the domestic market. Analogously, exchange rate

depreciation implies that the nation’s currency is losing purchasing power in international markets.

Average annual rate of depreciation with respect to the $US (%)

Copyright © 2019. McGraw-Hill Education (Australia) Pty Limited. All rights reserved.

Figure 17.2 shows average annual rates of inflation and nominal exchange rate depreciation for some South

and Central American countries from 1995 to 2013. Inflation is measured as the annual rate of change in the

country’s consumer price index; depreciation is measured relative to the US dollar. Figure 17.2 shows that, as the

PPP theory implies, countries with higher inflation relative to the United States during the 1995–2013 period

tended to experience the most rapid depreciation of their currencies.

1

Chile

0

0

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

–1

–2

Bolivia

–3

Colombia

–4

–5

–6

Dominican

Republic

Costa Rica

–7

Difference between the average annual domestic inflation rate and the US inflation rate (% points)

Figure 17.2 Inflation and currency depreciation in some South and Central American countries, 1995–2013

Note: High inflation relative to the US over this period was associated with rapid depreciation of the nominal exchange rate.

Source: Authors’ calculations based on International Monetary Fund 2018, ‘IMF data: Access to macroeconomic and financial data’,

http://data.imf.org/?sk=388DFA60-1D26-4ADE-B505-A05A558D9A42, accessed November 2018.

Bernanke, B., Olekalns, N., & Frank, R. (2019). Principles of macroeconomics. ProQuest Ebook Central <a onclick=window.open('http://ebookcentral.proquest.com','_blank')

href='http://ebookcentral.proquest.com' target='_blank' style='cursor: pointer;'>http://ebookcentral.proquest.com</a>

Created from usyd on 2021-06-23 12:42:18.

ole24015_ch17_431-464.indd

440

02/26/19 07:58 PM

Exchange rates and the open economy CHAPTER 17

Copyright © 2019. McGraw-Hill Education (Australia) Pty Limited. All rights reserved.

17.3.2 SHORTCOMINGS OF THE PPP THEORY

Empirical studies have found that the PPP theory is useful for predicting changes in nominal exchange rates over

the relatively long run. In particular, this theory helps to explain the tendency of countries with high inflation to

experience depreciation of their exchange rates, as shown in Figure 17.2. However, the theory is less successful in

predicting short-run movements in exchange rates.

An example of a dramatic failure of the PPP theory occurred in Australia over the course of 2003. As

Figure 17.1 indicates, during 2003 the value of the Australian dollar rose over 20 per cent relative to the currencies

of Australia’s trading partners. This strong appreciation was followed in April and May 2004 by a depreciation.

PPP theory could explain this roller-coaster behaviour only if inflation were far lower in Australia than in its

trading partners in 2003 and far higher in April and May of 2004. In fact, inflation was similar in Australia and

its trading partners throughout both periods.

Why does the PPP theory not always work well? Recall that this theory relies on the law of one price, which

says that the price of an internationally traded commodity must be the same in all locations. The law of one price

works well for goods such as grain or gold, which are standardised commodities that are traded widely. However,

not all goods and services are traded internationally, and not all goods are standardised commodities.

Many goods and services are not traded internationally because the assumption underlying the law of one

price—that transport costs are relatively small—does not hold for them. For example, for Indians to export

haircuts to Australia they would need to transport an Indian barber to Australia every time an Australian resident

desired a trim. Because transport costs prevent haircuts from being traded internationally, the law of one price

does not apply to them. Thus, even if the price of haircuts in Australia were double the price of haircuts in India,

market forces would not necessarily force prices towards equality in the short run. (Over the long run, some

Indian barbers might emigrate to Australia.) Other examples of non-traded goods and services are agricultural

land, buildings, heavy construction materials (whose value is low relative to their transportation costs) and

highly perishable foods. In addition, some products use non-traded goods and services as inputs: a McDonald’s

hamburger served in Moscow has both a tradable component (frozen hamburger patties) and a non-tradable

component (the labour of counter workers). In general, the greater the share of non-traded goods and services

in a nation’s output, the less precisely the PPP theory will apply to the country’s exchange rate. (Trade barriers,

such as tariffs and quotas, also increase the costs associated with shipping goods from one country to another.

Thus, trade barriers reduce the applicability of the law of one price in much the same way that physical

transportation costs do.)

The second reason the law of one price and the PPP theory sometimes fail to apply is that not all internationally

traded goods and services are perfectly standardised commodities, like grain or gold. For example, Australianmade cars and Japanese-made cars are not identical: they differ in styling, horsepower, reliability and other

features. As a result, some people strongly prefer one nation’s cars to the other’s. Thus, if Japanese cars cost 10

per cent more than Australian cars, Australian car exports will not necessarily flood the Japanese market, since

many Japanese will still prefer Japanese-made cars even at a 10 per cent premium. Of course, there are limits to

how far prices can diverge before people will switch to the cheaper product. But the law of one price, and hence

the PPP theory, will not apply exactly to non-standardised goods.

To summarise, the PPP theory works reasonably well as an explanation of exchange rate behaviour over the

long run but not in the short run. Because transportation costs limit international trade in many goods and

services, and because not all goods that are traded are standardised commodities, the law of one price (on which

the PPP theory is based) works only imperfectly in the short run. To understand the short-run movements of

exchange rates we need to incorporate some additional factors. In the next section we will study a supply and

demand framework for the determination of exchange rates.

⊳⊳ RECAP

Purchasing power parity implies that the exchange rate between two countries adjusts so that the respective

price levels in the two countries are equal when measured in units of a common currency. A further implication

of PPP is that the rate of depreciation of the exchange rate between two countries reflects the difference in

the inflation rates of the two countries.

Bernanke, B., Olekalns, N., & Frank, R. (2019). Principles of macroeconomics. ProQuest Ebook Central <a onclick=window.open('http://ebookcentral.proquest.com','_blank')

href='http://ebookcentral.proquest.com' target='_blank' style='cursor: pointer;'>http://ebookcentral.proquest.com</a>

Created from usyd on 2021-06-23 12:42:18.

ole24015_ch17_431-464.indd

441

02/26/19 07:58 PM

441

442

PART 4 OPEN-ECONOMY MACROECONOMICS

Purchasing power parity does a reasonable job of describing long-run movements in exchange rates; it

does less well as an explanation of short-run movements in exchange rates. Economists believe this is

because transportation costs and the fact that not all commodities are traded means that PPP works only

imperfectly in the short run.

LO 17.5, 17.6

17.4 T

HE DETERMINATION OF THE EXCHANGE RATE:

A SUPPLY AND DEMAND ANALYSIS

Although the PPP theory helps to explain the long-run behaviour of the exchange rate, supply and demand

analysis is more useful for studying its short-run behaviour. As we will see, dollars are demanded in the foreign

exchange market by foreigners who seek to purchase Australian goods and assets and are supplied by Australian

residents who need foreign currencies to buy foreign goods and assets. The equilibrium exchange rate is the value

of the dollar that equates the number of dollars supplied and demanded in the foreign exchange market. In this

section we discuss the factors that affect the supply and demand for dollars, and thus Australia’s exchange rate.

The principal suppliers of Australian dollars to the foreign exchange market are Australian households and firms.

Why would an Australian household or firm want to supply dollars in exchange for foreign currency? There are

two major reasons. First, an Australian household or firm may need foreign currency to purchase foreign goods or

services. For example, an Australian car importer may need yen to purchase Japanese cars, or an Australian tourist

may need yen to make purchases in Tokyo. Second, an Australian household or firm may need foreign currency

to purchase foreign assets. For example, an Australian superannuation fund may wish to acquire shares issued by

Japanese companies, or an individual Australian saver may want to purchase Japanese government bonds. Because

Japanese assets are priced in yen, the Australian household or firm will need to trade dollars for yen to acquire

these assets.

The supply of dollars to the foreign exchange market is illustrated in Figure 17.3. We will focus on the market

in which dollars are traded for Japanese yen, but bear in mind that similar markets exist for every other pair of

traded currencies. The vertical axis of Figure 7.3 shows the Australian–Japanese exchange rate as measured by

the number of yen that can be purchased with each dollar. The horizontal axis shows the number of dollars being

traded in the yen–dollar market.

Supply of dollars

Yen-dollar exchange rate

Copyright © 2019. McGraw-Hill Education (Australia) Pty Limited. All rights reserved.

17.4.1 THE SUPPLY OF DOLLARS

Figure 17.3 The supply and demand for dollars in

the yen–dollar market

e*

Demand for

dollars

0

Quantity of dollars traded

Note: The supply of dollars to the foreign exchange

market is upward sloping, because an increase in

the number of yen offered for each dollar makes

Japanese goods, services and assets more attractive

to Australian buyers. Similarly, the demand for dollars

is downward sloping, because holders of yen will be

less willing to buy dollars the more expensive they

are in terms of yen. The equilibrium exchange rate,

e*, also called the fundamental value of the exchange

rate, equates the quantities of dollars supplied and

demanded.

Bernanke, B., Olekalns, N., & Frank, R. (2019). Principles of macroeconomics. ProQuest Ebook Central <a onclick=window.open('http://ebookcentral.proquest.com','_blank')

href='http://ebookcentral.proquest.com' target='_blank' style='cursor: pointer;'>http://ebookcentral.proquest.com</a>

Created from usyd on 2021-06-23 12:42:18.

ole24015_ch17_431-464.indd

442

02/26/19 07:58 PM

Exchange rates and the open economy CHAPTER 17

Note that the supply curve for dollars is upward sloping. In other words, the more yen each dollar can buy,

the more dollars people are willing to supply to the foreign exchange market. Why? At given prices for Japanese

goods, services and assets, the more yen a dollar can buy, the cheaper those goods, services and assets will be in

dollar terms. For example, if a video game costs 5000 yen in Japan, and a dollar can buy 100 yen, the dollar price

of the video game will be $50. However, if a dollar can buy 200 yen, then the dollar price of the same video game

will be $25. Assuming that lower dollar prices will induce Australians to increase their expenditures on Japanese

goods, services and assets, a higher yen–dollar exchange rate will increase the supply of dollars to the foreign

exchange market. Thus the supply curve for dollars is upward sloping.

17.4.2 THE DEMAND FOR DOLLARS

In the yen–dollar foreign exchange market, demanders of dollars are those who wish to acquire dollars in

exchange for yen. Most demanders of dollars in the yen–dollar market are Japanese households and firms,

although anyone who happens to hold yen is free to trade them for dollars. Why demand dollars? The reasons

for acquiring dollars are analogous to those for acquiring yen. First, households and firms that hold yen will

demand dollars so that they can purchase Australian goods and services. For example, a Japanese firm that wants

to license Australian-produced software needs dollars to pay the required fees, and a Japanese student studying

in an Australian university must pay tuition in dollars. The firm or the student can acquire the necessary dollars

only by offering yen in exchange. Second, households and firms demand dollars in order to purchase Australian

assets. The purchase of Gold Coast real estate by a Japanese company or the acquisition of Telstra shares by a

Japanese pension fund are two examples.

The demand for dollars is represented by the downward-sloping curve in Figure 17.3. The curve slopes

downwards because the more yen a Japanese citizen must pay to acquire a dollar, the less attractive Australian

goods, services and assets will be. Hence the demand for dollars will be low when dollars are expensive in terms

of yen and high when dollars are cheap in terms of yen.

Copyright © 2019. McGraw-Hill Education (Australia) Pty Limited. All rights reserved.

17.4.3 EQUILIBRIUM VALUE OF THE DOLLAR

As mentioned earlier, Australia, like many countries, maintains a flexible, or floating, exchange rate, which means

that the value of the dollar is determined by the forces of supply and demand in the foreign exchange market. In

Figure 17.3 the equilibrium value of the dollar is e*, the yen–dollar exchange rate at which the quantity of dollars

supplied equals the quantity of dollars demanded. The equilibrium value of the exchange rate is also called the

fundamental value of the exchange rate. In general, the equilibrium value of the dollar is not constant but

changes with shifts in the supply of and demand for dollars in the foreign exchange market.

17.4.4 CHANGES IN THE SUPPLY OF DOLLARS

Recall that people supply dollars to the yen–dollar foreign exchange market in order to purchase Japanese goods,

services and assets. Factors that affect the desire of Australian households and firms to acquire Japanese goods,

services and assets will therefore affect the supply of dollars to the foreign exchange market. Some factors that

will increase the supply of dollars, shifting the supply curve for dollars to the right, include:

1. An increased preference for Japanese goods. For example, suppose that Japanese firms produce some

popular new consumer electronics. To acquire the yen needed to buy these goods, Australian importers will

increase their supply of dollars to the foreign exchange market.

fundamental value of

the exchange rate (or

equilibrium exchange rate)

The exchange rate that

equates the quantities of

the currency supplied and

demanded in the foreign

exchange market.

2. An increase in Australia’s real GDP. This will raise the incomes of Australians, allowing them to consume more goods and services. Some part of this increase in consumption will take the form of goods

imported from Japan. To buy more Japanese goods, Australians will supply more dollars to acquire the

necessary yen.

3. An increase in the real interest rate on Japanese assets. Recall that Australian households and firms acquire

yen in order to purchase Japanese assets as well as goods and services. Other factors, such as risk, being

held constant, the higher the real interest rate paid by Japanese assets, the more Japanese assets Australians

will choose to hold. To purchase additional Japanese assets, Australian households and firms will supply

more dollars to the foreign exchange market. There is an important caveat here concerning the likelihood of

Bernanke, B., Olekalns, N., & Frank, R. (2019). Principles of macroeconomics. ProQuest Ebook Central <a onclick=window.open('http://ebookcentral.proquest.com','_blank')

href='http://ebookcentral.proquest.com' target='_blank' style='cursor: pointer;'>http://ebookcentral.proquest.com</a>

Created from usyd on 2021-06-23 12:42:18.

ole24015_ch17_431-464.indd

443

02/26/19 07:58 PM

443

444

PART 4 OPEN-ECONOMY MACROECONOMICS

future exchange rate movements. If there is an expectation that the Australian dollar will appreciate in value

against the Japanese yen, then it need not be the case that an increase in the real interest rate on Japanese

financial assets translates into increased demand by holders of Australian currency for those Japanese

assets. Australian dollars are expected to be worth more yen, or equivalently yen are expected to be worth

fewer Australian dollars. Financial investors will understand that the apparent higher returns from Japanese

assets may be illusory once those returns are converted into dollars. To guarantee that an increase in the

real interest rate in Japan increases the supply of Australian dollars, therefore, requires an assumption that

no change in the exchange rate is expected.

Conversely, with all else being unchanged, reduced demand for Japanese goods, a lower Australian GDP

or a lower real interest rate on Japanese assets will reduce the number of yen Australians need, in turn

reducing their supply of dollars to the foreign exchange market and shifting the supply curve for dollars

to the left. Of course, any shift in the supply curve for dollars will affect the equilibrium exchange rate, as

Example 17.5 shows.

EXAMPLE 17.5 – VIDEO GAMES, THE YEN AND THE DOLLAR

Suppose Japanese firms come to dominate the video game market, with games that are more

exciting and realistic than those produced in Australia. All else being equal, how will this change

affect the relative value of the yen and the dollar?

S

S′

Yen-dollar exchange rate

Copyright © 2019. McGraw-Hill Education (Australia) Pty Limited. All rights reserved.

The increased quality of Japanese video games will increase the demand for the games in

Australia. To acquire the yen necessary to buy more Japanese video games Australian importers will

supply more dollars to the foreign exchange market. As Figure 17.4 shows, the increased supply

of dollars will reduce the value of the dollar. In other words, a dollar will buy fewer yen than it did

before. At the same time, the yen will increase in value: a given number of yen will buy more dollars

than it did before.

E

e*

e*′

F

D

0

Quantity of dollars traded

Figure 17.4 An increase in the supply of dollars lowers the value of the dollar

Note: Increased Australian demand for Japanese video games forces Australians to supply more dollars to the foreign exchange

market to acquire the yen they need to buy the games. The supply curve for dollars shifts from S to S′, lowering the value of the

dollar in terms of yen. The fundamental value of the exchange rate falls from e* to e*′.

Bernanke, B., Olekalns, N., & Frank, R. (2019). Principles of macroeconomics. ProQuest Ebook Central <a onclick=window.open('http://ebookcentral.proquest.com','_blank')

href='http://ebookcentral.proquest.com' target='_blank' style='cursor: pointer;'>http://ebookcentral.proquest.com</a>

Created from usyd on 2021-06-23 12:42:18.

ole24015_ch17_431-464.indd

444

02/26/19 07:58 PM

Exchange rates and the open economy CHAPTER 17

CONCEPT CHECK 17.4

Suppose Australia goes into a recession and real GDP falls. All else being equal, how is this economic weakness likely to affect the

value of the dollar?

17.4.5 CHANGES IN THE DEMAND FOR DOLLARS

The factors that can cause a change in the demand for dollars in the foreign exchange market, and thus a shift of

the dollar demand curve, are analogous to the factors that affect the supply of dollars. Factors that will increase

the demand for dollars include:

• An increased preference for Australian goods. For example, Japanese firms might find that Australian-built

trucks are superior to others and decide to expand the number of Australian-made trucks in their fleets. To buy the Australian trucks, Japanese firms would demand more dollars on the foreign exchange market.

• An increase in real GDP abroad, which implies higher incomes abroad and thus more demand for imports

from Australia.

• An increase in the real interest rate on Australian assets, which would make those assets more attractive to foreign savers. To acquire Australian assets, Japanese savers would demand more dollars. As in Section 17.4.4, when we discussed the effect of an increase in Japan’s real interest rate on the supply of

dollars, here we assume no expected change in the exchange rate.

Copyright © 2019. McGraw-Hill Education (Australia) Pty Limited. All rights reserved.

⊳⊳ RECAP

Australian dollars are supplied to the international currency market because of Australians acquiring foreign

currency to pay for imports or for purchases of foreign financial assets. As the exchange rate becomes

stronger, the supply of Australian dollars to the international currency market will increase.

Australian dollars are demanded in the international currency market as a result of foreigners acquiring

Australian currency to pay for exports or for purchases of Australian financial assets. As the exchange rate

becomes weaker, the demand for Australian dollars in the international currency market will increase.

The exchange rate will adjust until the supply of and demand for Australian dollars in the international

currency market is equalised.

All else being unchanged, the supply of Australian dollars will increase in the international currency

market if an increase in the level of real GDP in Australia increases the demand for imports or if Australian

interest rates are lower relative to the rest of the world. The supply of Australian dollars will decrease in the

international currency market if a decrease in the level of real GDP in Australia decreases the demand for

imports, or if Australian interest rates are higher relative to the rest of the world.

All else being unchanged, the demand for Australian dollars will increase in the international currency market

if an increase in the level of real GDP in other countries increases the demand for exports or if Australian

interest rates are higher relative to the rest of the world. The demand for Australian dollars will decrease in the

international currency market if a decrease in the level of real GDP in other countries decreases the demand

for exports or if Australian interest rates are lower relative to the rest of the world. Changes in the preference

for Australian-made commodities can also affect the demand for Australian currency.

17.5 MONETARY POLICY AND THE EXCHANGE RATE

LO 17.6

Of the many factors that could influence a country’s exchange rate, among the most important is the monetary

policy of the country’s central bank. As we will see, monetary policy affects the exchange rate primarily through

its effect on the real interest rate.

Suppose the Reserve Bank is concerned about inflation and tightens Australian monetary policy in response.

The effects of this policy change on the value of the dollar are shown in Figure 17.5. Before the policy change,

Bernanke, B., Olekalns, N., & Frank, R. (2019). Principles of macroeconomics. ProQuest Ebook Central <a onclick=window.open('http://ebookcentral.proquest.com','_blank')

href='http://ebookcentral.proquest.com' target='_blank' style='cursor: pointer;'>http://ebookcentral.proquest.com</a>

Created from usyd on 2021-06-23 12:42:18.

ole24015_ch17_431-464.indd

445

02/26/19 07:58 PM

445

446

PART 4 OPEN-ECONOMY MACROECONOMICS

Yen-dollar exchange rate

S′

S

e*′

e*

F

E

Figure 17.5 A tightening of monetary policy

strengthens the dollar

D′

D

0

Copyright © 2019. McGraw-Hill Education (Australia) Pty Limited. All rights reserved.

Quantity of dollars traded

Note: Tighter monetary policy in Australia raises the

domestic real interest rate, increasing the demand

for Australian assets by foreign savers and reducing

the demand for foreign assets by Australian savers.

The demand curve shifts from D to D′ and the supply

curve shifts from S to S′, leading the exchange rate

to appreciate from e* to e*′.

the equilibrium value of the exchange rate is e*, at the intersection of the supply curve, S, and the demand curve,

D (point E in the figure). The tightening of monetary policy raises the domestic Australian real interest rate,

r, making Australian assets more attractive to foreign financial investors. The increased willingness of foreign

investors to buy Australian assets increases the demand for dollars, shifting the demand curve rightwards from

D to D′. At the same time foreign financial assets look less attractive to Australian financial investors, thus

decreasing the supply of dollars, shifting the supply curve leftwards from S to S′. As you can see from Figure 17.5,

the equilibrium point shifts from E to F and the equilibrium value of the dollar rises from e* to e*′. However, the

caveats from Sections 17.4.4 and 17.4.5 still apply; to guarantee that these curves move in this way we assume no

anticipated change in the exchange rate.

In short, all else remaining unchanged, a tightening of monetary policy by the Reserve Bank raises the demand

for dollars and decreases the supply of dollars, causing the dollar to appreciate. By similar logic, an easing of

monetary policy, which reduces the real interest rate, would reduce the demand for the dollar and increase its

supply, causing it to depreciate.

THINKING AS AN ECONOMIST 17.2

Why did the dollar depreciate by 12 per cent over 2018?

Over the period from 25 January 2018 to 23 October 2018, the value of the Australian dollar relative to

the US dollar decreased from 0.8094 to 0.7063. What can explain this change?

Moves towards a relatively tighter monetary policy in the United States, and the associated high

real interest rate, at a time when the interest rate in Australia was on hold, was an important cause of

the Australian dollar’s depreciation during this period. The federal funds rate, which is the interest rate

targeted by the US Federal Reserve, increased three times.The target cash interest rate in Australia over

this period was left unchanged—see Figure 17.6. This meant that US assets became relatively more

attractive to both foreign and domestic asset holders compared with Australian assets.

Bernanke, B., Olekalns, N., & Frank, R. (2019). Principles of macroeconomics. ProQuest Ebook Central <a onclick=window.open('http://ebookcentral.proquest.com','_blank')

href='http://ebookcentral.proquest.com' target='_blank' style='cursor: pointer;'>http://ebookcentral.proquest.com</a>

Created from usyd on 2021-06-23 12:42:18.

ole24015_ch17_431-464.indd

446

02/26/19 07:58 PM

Exchange rates and the open economy CHAPTER 17

2.50

2.00

US target federal funds rate

Australian target cash interest rate

Per cent

1.50

1.00

0.50

25

20

18

-0

9-

25

20

18

-0

8-

25

20

18

-0

7-

25

20

18

-0

6-

25

20

18

-0

5-

25

20

18

-0

4-

25

20

18

-0

3-

25

2-0

18

20

20

18

-0

1-

25

0.00

Year

Figure 17.6 Official interest rates in Australia and the United States

Copyright © 2019. McGraw-Hill Education (Australia) Pty Limited. All rights reserved.

Note: Higher interest rates in the United States relative to Australia meant that Australian assets were relatively less

attractive to both foreign and domestic asset holders, weakening the Australian dollar.

Source: Based on Federal Reserve Bank of St Louis 2018, ‘Federal funds target range: upper limit’, https://fred.stlouisfed.org/

series/DFEDTARU; Reserve Bank of Australia 2018, ‘Statistical tables’, https://www.rba.gov.au/statistics/tables/#interestrates; Federal Reserve Bank of St Louis 2018, ‘Federal Reserve economic data’, https://fred.stlouisfed.org.

17.5.1 THE EXCHANGE RATE AS A TOOL OF MONETARY POLICY

In a closed economy, monetary policy affects aggregate demand solely through the real interest rate. For example,

by raising the real interest rate, a tight monetary policy reduces consumption and investment spending. We will

see next that in an open economy with a flexible exchange rate, the exchange rate serves as another channel for

monetary policy, one that reinforces the effects of the real interest rate.

To illustrate, suppose that policymakers are concerned about inflation and decide to restrain aggregate demand.

To do so they increase the real interest rate, reducing consumption and investment spending. But, as Figure 17.5

shows, the higher real interest rate may also increase the demand for dollars and decrease the supply, causing the

dollar to appreciate. The stronger dollar, in turn, further reduces aggregate demand. Why? As we saw in discussing the

real exchange rate, a stronger dollar reduces the cost of imported goods, increasing imports at the expense of some

expenditure on domestically produced goods and services. It also makes exports more costly to foreign buyers, which

tends to reduce exports—recall that exports is one of the components of aggregate demand. Thus, by reducing exports

and increasing imports, a stronger dollar (more precisely, a higher real exchange rate) reduces aggregate demand.

In sum, when the exchange rate is flexible, a tighter monetary policy reduces exports and increases imports

(through a stronger dollar) as well as consumption and investment spending (through a higher real interest

rate). Conversely, an easier monetary policy weakens the dollar, stimulates exports and discourages imports,

reinforcing the effect of the lower real interest rate on consumption and investment spending. Thus, relative

to the case of a closed economy we studied earlier, monetary policy is more effective in an open economy with a

flexible exchange rate.

Bernanke, B., Olekalns, N., & Frank, R. (2019). Principles of macroeconomics. ProQuest Ebook Central <a onclick=window.open('http://ebookcentral.proquest.com','_blank')

href='http://ebookcentral.proquest.com' target='_blank' style='cursor: pointer;'>http://ebookcentral.proquest.com</a>

Created from usyd on 2021-06-23 12:42:18.

ole24015_ch17_431-464.indd

447

02/26/19 07:58 PM

447

448

PART 4 OPEN-ECONOMY MACROECONOMICS

⊳⊳ RECAP

As monetary policy affects the level of interest rates, it can have an impact on the exchange rate. All else being

unchanged, a tightening of monetary policy, which pushes up interest rates, is likely to strengthen the domestic

currency; a loosening of monetary policy, which pushes down interest rates, is likely to weaken the currency.

LO 17.7

17.6 FIXED EXCHANGE RATES

So far we have focused on the case of flexible exchange rates, the relevant case for most industrial countries

like Australia. However, the alternative approach, fixing the exchange rate, has been quite important historically

and is still used in many countries, especially small or developing nations. In this section we will see how our

conclusions change when the nominal exchange rate is fixed rather than flexible. One important difference is

that when a country maintains a fixed exchange rate, its ability to use monetary policy as a stabilisation tool is

greatly reduced.

Copyright © 2019. McGraw-Hill Education (Australia) Pty Limited. All rights reserved.

17.6.1 HOW TO FIX AN EXCHANGE RATE

devaluation

A reduction in the official

value of a currency

(in a fixed exchange

rate system).

revaluation

An increase in the official

value of a currency

(in a fixed exchange

rate system).

overvalued exchange rate

An exchange rate that

has an officially fixed

value greater than its

fundamental value.

undervalued exchange rate

An exchange rate that has

an officially fixed value less

than its fundamental value.

In contrast to a flexible exchange rate, whose value is determined solely by supply and demand in the foreign

exchange market, the value of a fixed exchange rate is determined by the government (in practice, usually the

finance ministry or treasury department, with the cooperation of the central bank). Today, the value of a fixed

exchange rate is usually set in terms of a major currency (e.g. Hong Kong pegs its currency one-for-one to the

US dollar), or relative to a ‘basket’ of currencies, typically those of the country’s trading partners. Historically,

currency values were often fixed in terms of gold or other precious metals, but in recent years precious metals

have rarely if ever been used for that purpose.

Once an exchange rate has been fixed, the government usually attempts to keep it unchanged for some time.

(There are exceptions to this statement. Some countries employ a crawling peg system, under which the exchange

rate is fixed at a value that changes in a gradual way over time. For example, the government may ensure that the

value of the fixed exchange rate will fall 2 per cent each year. Other countries use a target zone system, in which

the exchange rate is allowed to deviate by a small amount from its fixed value. To focus on the key issues, we will

assume that the exchange rate is fixed at a single value for a protracted period.) However, sometimes economic

circumstances force the government to change the value of the exchange rate. A reduction in the official value

of a currency is called a devaluation; an increase in the official value is called a revaluation. The devaluation of

a fixed exchange rate is analogous to the depreciation of a flexible exchange rate; both involve a reduction in the

currency’s value. Conversely, a revaluation is analogous to an appreciation.

The supply and demand diagram we used to study flexible exchange rates can be adapted to analyse fixed

exchange rates. Let us consider the case of a country called Latinia, whose currency is called the peso. Figure 17.7

shows the supply and demand for the Latinian peso in the foreign exchange market. Pesos are supplied to the

foreign exchange market by Latinian households and firms who want to acquire foreign currencies to purchase

foreign goods and assets. Pesos are demanded by holders of foreign currencies who need pesos to purchase

Latinian goods and assets. Figure 17.7 shows that the quantities of pesos supplied and demanded in the foreign

exchange market are equal when a peso equals 0.1 dollars (10 pesos to the dollar). Hence 0.1 dollars per peso

is the fundamental value of the peso. If Latinia had a flexible exchange rate system, the peso would trade at 10

pesos to the dollar in the foreign exchange market.

But let us suppose that Latinia has a fixed exchange rate and that the government has decreed the value

of the Latinian peso to be 8 pesos to the dollar, or 0.125 dollars per peso. This official value of the peso,

0.125 dollars, is indicated by the solid horizontal line in Figure 17.7. Notice that it is greater than the equilibrium

value, corresponding to the intersection of the supply and demand curves. When the officially fixed value of

an exchange rate is greater than its fundamental value, the exchange rate is said to be overvalued. The official

value of an exchange rate can also be lower than its fundamental value, in which case the exchange rate is said to

be undervalued.

Bernanke, B., Olekalns, N., & Frank, R. (2019). Principles of macroeconomics. ProQuest Ebook Central <a onclick=window.open('http://ebookcentral.proquest.com','_blank')

href='http://ebookcentral.proquest.com' target='_blank' style='cursor: pointer;'>http://ebookcentral.proquest.com</a>

Created from usyd on 2021-06-23 12:42:18.

ole24015_ch17_431-464.indd

448

02/26/19 07:58 PM

Exchange rates and the open economy CHAPTER 17

Dollar-peso exchange rate

Supply of pesos

A

0.125 dollar–

peso

B

Official value

Fundamental

value

0.10 dollar–

peso

Demand for

pesos

0

Quantity of pesos traded

Figure 17.7 An overvalued exchange rate

Copyright © 2019. McGraw-Hill Education (Australia) Pty Limited. All rights reserved.

Note: The peso’s official value ($0.125) is shown as greater than its fundamental value ($0.10), as determined by supply and demand

in the foreign exchange market. Thus the peso is overvalued. To maintain the fixed value, the government must purchase pesos in the

quantity AB each period.

In this example, Latinia’s commitment to hold the peso at 8 to the dollar is inconsistent with the fundamental

value of 10 to the dollar, as determined by supply and demand in the foreign exchange market (the Latinian peso

is overvalued). How could the Latinian Government deal with this inconsistency?

The most widely used approach to maintaining an overvalued exchange rate is for the government to become

a demander of its own currency in the foreign exchange market. Figure 17.7 shows that at the official exchange

rate of 0.125 dollars per peso, the private sector supply of pesos (point B) exceeds the private sector demand for

pesos (point A). To keep the peso from falling below its official value, in each period the Latinian Government

could purchase a quantity of pesos in the foreign exchange market equal to the length of the line segment AB in

Figure 17.7. If the government followed this strategy then at the official exchange rate of 0.125 dollars per peso,

the total demand for pesos (private demand at point A plus government demand AB) would equal the private

supply of pesos (point B). This situation is analogous to government attempts to keep the price of a commodity,