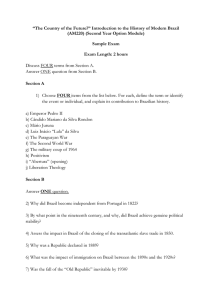

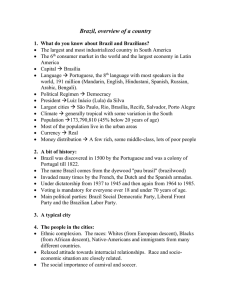

Class Action in Brazil Overview, Current Trends and Case Studies (2)

advertisement