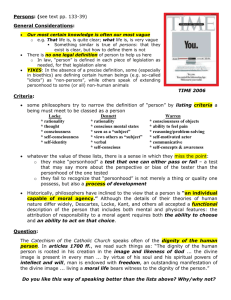

SCHOOL OF THEOLOGY AND MISSIONS THEOLOGY DEPARTMENT MPTS650 AFRICAN TRADITIONAL RELIGION, PHILOSOPHY AND CULTURAL VALUES LECTURER: DR. MRS. DORIS YALLEY BAFFOE PRINCE GRS/TMP/20/0/2612 TOPIC: AFRICAN IDEAS OF COMMUNITY - PERSONHOOD, SOLIDARITY & COMMUNALISM TITLE: EXAMINING THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN PERSONHOOD AND COMMUNITY INTRODUCTION It is mostly the case of research work or study trying to strike the differences between the concept of personhood and community which leads to finding which of the ideologies or moral thought is superior. This research work will try to rather draw views to establish a connection between the two concepts. The individual is the issue or problem that occupied Rawls' neo-Kantianism in A theory of justice (1971), as well as other individualist thinkers including Robert Nozick, David Gauthier, Ronald Dworkin, and, to a lesser degree, Kymlicka. From his Hegelian traditions, contemporary ‘communitarian authors' like Alasdair MacIntyre, Michael Sandel, Michael Walzer, and Charles Taylor focus fundamentally on this same notion of ‘the person.' To ask the question, “does the individual's existence belong to him or does it belong to the community?” for Menkiti, for example, would be incomprehensible and obnoxious, if not abominable, because, in his opinion, “it is the community which defines the person as person, not some isolated static quality of reason, will, or memory” (1984, pp. 171-172) and that, “a community defines the person as person not some isolated static quality of rationality, will or memory” (1984, pp. 171-172) and that as far as Africans are concerned, the reality of the communal world takes precedence over the reality of individual life histories, whatever these may be,” says the author. (Page 180). The aim of this paper is to illustrate the "relationship between personhood and communalism within the African culture. In this research work, I will analyse the concept of personhood and community based on what some scholars proposed and opposed whiles sharing my views on these concepts. Also I will then finally try to examine the relationship between these two concepts. “Wisdom is like a baobab tree; no one person can accept it,” says an African proverb. LITERATURE REVIEW “Negro-African society places more emphasis on the collective than on the individual, more on unity than on the individual's action and needs, more on the communion of persons than on their autonomy,” writes Senghor. “We live in a community.” (p. 49, 1964). He backs up his point by saying that "NegroAfrican culture is collectivist or, more specifically collective, since it is ratified." “If you want to go far, go alone,” says an African proverb. Go together if you want to go far.” The culture, according to Wiredu and Gyekye, “alone constitutes the background, social or cultural space, in which the actualization of the individual person's possibilities will take place, providing the individual person with the opportunity to express his individuality, to acquire and grow his personality and to fully become the kind of person he wants”. (1992, p. 106) According to Mbiti, the person is created by the community, and without the community, the individual will not exist. ‘I am, since we are; and because we are, so I am,' the person can only say. (1970, p. 141; emphasis mine). According to this way of thinking, a human being becomes real only through her interactions with others in a community or group, and as a result, the growth of an individual is limited. So, in Kenyatta's words, "nobody is an isolated person." Or, to put it another way, his individuality is a secondary reality about him; first and foremost, he is the relative and contemporary of many people.” (p. 297, 1965). Instead of the Cartesian individualistic concept of a human, such an African communitarian interpretation of being would be better captured as “I am connected, therefore we are.” Other scholars have noted that African moral philosophy contains strands of individualism. For example, in defending an African environmental ethics, Kevin Behrens (2011) notes some strains of individualism in African moral thinking, but ultimately prefers a communalistic account. In his influential essay, Thad Metz (2007) ”Toward an African Moral Theory” had stated that he had discovered that most of the literature in African moral thinking takes an individualist orientation, but he goes on to defend a community-based moral theory as the most logical way to interpret African ethics in his survey of the literature (Metz, 2007; 2010). THE CONCEPT OF COMMUNATARIANISM A well-known term, ‘communitarianism,' often comes up in current philosophical debates about the arrangement of the African nation. Communitarianism is described as "the belief that the community (i.e., society) is the focal point of the actions of individual members of the society." Many African thinkers regard the African culture as communitarian, as will be demonstrated shortly. Many African thinkers consider the African social structure to be communitarian, but there have been some differences between Gyekye and other scholars about how correct this description of the African social structure is. African thinking tends to offer a variety of viewpoints on existence, as well as the world and what it comprises. Given this, as well as the current situation in Africa, where many of its educated people are being exposed to Western concepts of individual rights, there is the potential for differing interpretations of how the African social system can compensate for or conceive of the common or community good (and how to achieve it). Despite the fact that they are members of a community, fundamental cultural characteristics and allegiances are believed to be shared by a group of people. The concept of a community can thus be described as "the concept of a group of people living together in a specific location and sharing certain commonalities of history, philosophy, belief system, beliefs, lineage, kinship, or political system" (Ikuenobe 2006: 1) Because of the aforementioned differences among Africa's educated people, especially philosophers, and the fact that they can each defend their positions with strong arguments, the African (sense of) community cannot be easy. The term "culture" in this paper refers to a "cultural community." As formulated by African academics, the general perspective of the African cultural community's overall perspective, as formulated by African scholars, must be grasped in its entirety, including all historical underpinnings. For example, shortly after the official end of the Cold War, some African states' founding fathers, such as Kaunda, Nkrumah, Nyerere, and Senghortilt, changed their allegiances to socialism. Socialism could be expressed in African words, and the socialist state's social system was comparable to, if not identical to, the African social structure. Mbiti and Menkiti also argued for the African social system's enormously social character and its ontological primacy over the person (Mbiti 1989: 141; Menkiti 1984: 171- 173). Nonetheless, with Gyekye's theory of "moderate communitarianism" (Gyekye 1995: 154-162), the discussion of the idea took a significant philosophical turn, with a more detailed exposition in his Tradition and Modernity. Any minor disruption in the social equilibrium is bound to lead to this lack of confidence in group life in a social setting where the person sees himself as supreme, independent, and self-governing. In a similar way, when a person is confronted with life problems that he cannot solve on his own, he becomes distraught; feeling existentially alone in the world, the individual becomes cranky and comes to conclude that community is a clog, obstructive and encumbering, Unlike the attitude mentioned above, Africans are unlikely to give absolute power to someone who is at odds with the party. Africans, on the other hand, conclude that a person's life is only important in the sense of their culture. To put it another way, it is in interacting with other members of society rather than living in isolation. The potent force of what is known as "the will of the nation" provides the evident curtailment of a person's power to do as he wills among the Igbo people of Nigeria, as well as among other African peoples in general. In Africa, as T. U. Nwala points out, “the being of the community is greater than, and prior to, that of any of its individual members, since the being of the community as a whole is larger than, and prior to, that of any of its individual members.” Opoku (1978: 92) argues that the saying “a man is a man because of others, and life is when you are together, alone you are an animal” is a common one in Africa, emphasizing this notion of the social essence of creation. Community life contributes to a sense of belonging and security among society's members. But it does so much more: it also contributes to the development of respect for all members of society. And, according to W. E. Abraham, in Africa, society is traditionally conceived as having "a sacral unity, which includes its living members, its dead members" (who survive in less substantial form) (Abraham 1992:25). Similarly, culture serves as a bulwark for the people' common interests to a large degree. J. S. Mbiti's argument that "the personality does not and cannot exist alone except corporately" in Africa supports Abraham's viewpoint (Mbiti 1969:108) It is important to note that the communitarian concept of community is not to be confused with the character portrayed in social contract theories, in which agreed collaboration is centered on the quest for mutual benefits. Such a notion of community, in the communitarian view, is understood as causal dependence between "the person" and her "community." defended by individualists like Gauthier, (1986, pp. 330-355) not only undermines the very identity. THE PERSONHOOD CONCEPT Ifeanyi Menkiti, a Nigerian philosopher, was the first to identify the normative concept of personhood. It applies to people who live morally upright lives (Menkiti 1984, 2004) In Akan philosophy, personhood is described in moral terms, according to Gyekye. According to him, someone is called a ‘person' if she has a disposition that is largely ethical in the group.( Gyekye 1992: 109-110) By virtue of the person experiences or relationships with other members of the community, as well as her general choices of behavior in life, such an individual is deemed to be a source of goodness to the community. Menkiti is based on Mbiti's concept of , "I am because we are, and because we are, so I am," says an African. "It is through rootedness in an ongoing human culture that the individual comes to see himself as man, and it is through first understanding this community as a stubborn perduring truth of the psychological universe that the individual also comes to know himself as man." (Menkiti 1984:171-172) Kwasi Wiredu and Kwame Gyekye are without a doubt two of the most prominent moral thinkers in African philosophy. Both of them, interestingly, defend humanism (Molefe, 2015). "Humanism" is a metaethical thesis that moral properties are better interpreted in natural terms, specifically in terms of some human property (Wiredu, 1992; Gyekye, 1995). Wiredu (1992: 194) uses the Akan maxim "onipa na ohia" to promote personhood, interpreting it to mean "all human meaning derives from human interests." “The first axiom of all Akan axiological philosophy is that man or woman is the indicator of all value,” he writes elsewhere (1996: 65) Individualism is perfectly evident in Wiredu's moral philosophy. The fact that Wiredu defends humanism as a meta-ethical philosophy and posits human interests or wellbeing as the universal moral standard answers the question of whether his moral theory is thoroughly individualistic. Gyekye's moral philosophy is in the same boat. He is also a humanist, which means he would base morality on certain human property because he excludes God from morality in certain ways (Gyekye, 2010). “All other values are reducible fundamentally to the meaning of well-being... all things are important insofar as they improve... well-being... as a „master value,” says Gyekye emphatically (Gyekye, 2004: 41). So, Gyekye is a Wiredu fan. As a result, we have two powerful moral theorists defending a humanistic meta-ethics that locates morality in certain human property. As a result, Akan morality, as embodied by these two prominent African philosophers, is individualistic in that it is based on certain human property, specifically well-being. The difference is that if communality is conceived as "the collective," it becomes a matter of personal preference as to whether or not people choose to be a member of "the community." Personism, on the other hand, defends the viewpoint that communality, like individuality, is not a choice for the individual. To put it another way, according to the personist study, an individual does not choose to be special. He doesn't want to be communal (i.e. relational) either. As a result, it will not be a matter of mediating between two distinct bodies in order to give rise to liberalist or "moderate communitarian" claims like those advanced by Gyekye, a renowned African philosopher (1995, pp. 154-162). The primary focus of morality becomes how individuals react to this individualistic aspect of life. Gyekye's normative theory, for example, is consequentialist in the sense that it allows us to encourage individual well-being, but these three religious thinkers may be construed as defending a self-realization approach to ethics, which requires agents to develop or maintain their vitality through perfecting their characters, or so I understand them (Bujo, 2001: 88; Shutte, 2001: 14). In light of the above, we can see that in both secular and religious approaches to ethics, there is a tendency in an African tradition to regard individualism as a hallmark of moral theorization. As a consequence, the following findings by Metz are not surprising. ”It's a cliché to claim that dominant Western moral views are "individualistic," while African moral views are "communitarian," so it's odd that the most popular theoretical interpretations of ubuntu, which I've examined above, are all more "individualistic" than "communitarian." (Metz, 2007:333) However, according to African scholars, normative considerations are "germane" or "more prevalent" in this tradition (Ikuenobe, 2006: 117; Wiredu, 2009: 13). “There is an African conception of personhood that is not only distinct from Western notions, but also foundational and characteristic of African philosophical thought,” according to Behrens (2013: 105) This idea, we are told, is different from what one might find in the West. It is also said to be both fundamental and distinctive in African philosophical thinking. As a result, it is unsurprising that Metz's review of African ethics literature concludes that "This is possibly the prevailing understanding of African ethics" (2007: 331). It's also worth noting that African scholars have repeatedly stated that the best way to understand communitarianism is through the concept of personhood (Gyekye, 1992: 102; Gyekye, 1997: 49; Mbigi, 2005: 75; Wiredu 2008: 336) ‘Moderate communitarianism,' according to Gyekye, expresses the concept that, while African culture is communitarian in nature, it still allows for certain autonomy and/or individual rights. However, Gyekye's position has been criticized for incoherence in his conceptions of "individual, personhood, and culture" as a result of "difficulties existent in Gyekye's own claims" that result in a lack of clarification (Majeed, 2018, p. 36). The difficulty of subsuming individuality into ‘community' is faced by the same. The argument here is that Gyekye's version of "moderate communitarianism" is not as moderate as he claims; that the supposed divide between his viewpoint and the "radical communitarian" viewpoint he criticizes might not be as broad as he claims (Famakinwa, 2011). THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN PERSONHOOD AND COMMUNITY/COMMUNITARIANISM The positions of Mbiti and Menkiti on personhood and Community can be summarized as follows: a person has a propensity to behave morally and has the general social good or the community's interest at heart. The group depends on its members' goodness, which is provided by the individual. This is an example of how personhood and culture are connected. Yet, it is Gyekye's description of Mbiti and Menkiti as "radical" communitarians that has led him to label them as "radical" communitarians. Gyekye's roles on Mbiti and Menkiti, on the other hand, are difficult to come by. This has influenced Martin Ajei's presentation of Gyekye's criticism of Menkiti, for example. Gyekye considers Menkiti as a "radical communitarian," according to Ajei (2015: 497). (extreme communitarian). However, his claim that Gyekye regards Menkiti as such is debatable, given Menkiti's belief that society in the African social setting "defines the individual as person... and personhood is something that must be earned, not given simply because one is born of human seed." This interrogation will focus not only on Ajei's interpretations, but also on the flaws in Gyekye's own claims against Menkiti. To begin with, Gyekye, contrary to Ajei's belief, sometimes affirms (but does not deny) that personhood must be achieved, and he (Gyekye) does not deny that not everyone is considered a person. According to Gyekye, "much is anticipated" in Akan culture. The promotion or practice of moral virtue is seen as fundamental to a person's identity. (1992: 109). As a result, the Akan will describe such a person as a "true (human) person" (ye onipa paa) who is "absolutely pleased with, and deeply appreciative of, the high standards of morality of a person's behavior." (1992:109). This means that, since not all humans would be able to demonstrate high moral standards in order to be considered "persons" or "true human persons," Gyekye indicates that personhood would not be achieved by all. This implies that personhood can be attained and that human beings do not automatically achieve this moral status. Indeed, Gyekye admits that ‘some expressions in Akan language, as well as judgments or evaluations made about people's lives and actions, give the impression that the society defines and confers personhood' (1992: 108-109). And that there are certain "common standards and values" in the Akan culture to which "a person's conduct, if he is a person, ought to adhere" (Gyekye 1992: 109). The ultimate communal character of morals, norms, and moral virtues can be seen in Gyekye's list of actions: "generosity, kindness, sympathy, benevolence, respect, and empathy for others; in short, any action or behavior that promotes the welfare of others" (1992: 109). In contrast to Menkiti, Gyekye offers an additional explanation of the moral conception of the individual in Akan philosophy: the human being is ‘considered to possess an inherent capacity for goodness, for performing morally correct acts...' (1992: 109). ‘Moral capacities as such cannot be said to be implanted by, catered for, or bestowed by the society,' Gyekye observes. (1992, page 111). Gyekye acknowledges that the community can play a part in a person's spiritual life, such as through "moral teaching, guidance, admonition, and the application of sanctions" (1992: 111). Gyekye's change is partially an effort to reduce the force or consequences of the communal obligation of moral values conformity (which he has committed to in the preceding paragraph). He correctly predicts that if the preceding paragraph's logic is maintained, it would be difficult to dismiss Menkiti's version of communitarianism. Because, if following moral principles and communal values ensures personhood, and the community enforces this and determines which individuals are doing so, then the community is the determinant of personhood in some way. Gyekye's presentation of the inherent dimension of personhood, on the other hand, is somewhat vague. He sets out to present it in contrast to the concept of communal conferment of personhood, which is based on the ‘processual' acquisition of moral personhood. That a human being is a human being regardless of age or social status. Personhood may be fully realized in a culture, but it is not gained or accomplished as one progresses through society.' (1992: 108) Menkiti's idea that the community "fully defines or confers personhood" is something Gyekye rejects and regards as extreme (1992: 111). In comparison to Menkiti, Gyekye gives another understanding of the moral conception of the person in Akan philosophy: identifying the human being as a person (onipa), He's thought to have an inherent potential for virtue, for carrying out morally correct acts... (Ibid., p. 109). However, as Gyekye points out, “[m]oral capacities as such cannot be assumed to be implanted, catered for, or bestowed by the community.” (1992: 111). Gyekye acknowledges that the community can play a part in a person's spiritual life, such as through "moral teaching, guidance, admonition, and the application of sanctions" (1992: 111). Gyekye's change is partially an effort to reduce the force or consequences of the communal obligation of moral values conformity. He correctly predicts that if the preceding paragraph's logic is maintained, it would be difficult to dismiss Menkiti's version of communitarianism. Because, if following moral principles and communal values ensures personhood, and the community enforces this and determines which individuals are doing so, then the community is the determinant of personhood in some way. As a result, he adds to the communal aspect the individual's right to "execute" her own "life style and ventures" – primarily due to her rationality – to determine who he or she is (1992: 111-112). Another manner in which personhood is linked to communitarianism is that a person who wishes to be labeled as a communitarian or as having achieved the status of personhood can only do so by achieving the status of personhood. These are granted to an individual (onipa) by the way she behaves. Furthermore, communitarianism and personhood tend to be linked in quality and direction as a philosophy of action. If one is or is not respecting the tenets of communitarianism, it is determined by the nature (goodness or badness) of one's actions; and the direction in which the requirements of both personhood and communitarianism lead an individual. CONCLUSION In terms of personhood, I believe that the prospect of moderate communitarian morality still lies in communal moral expectations for the common good and the upholding of moral norms. It isn't within the realm of moral capability. An entity is considered a ‘person' (onipa) in this sense when she, for example, contributes to moral acts and the promotion of the well-being of others. This sense of personhood is complex and distinct from the static sense of the moral person, which Gyekye briefly touches on in his discussion of the normative conception of the person. Personhood, in the static sense, is merely a capacity for moral action (which a human being still possesses even if she has not acted) that cannot be obtained in the future (since the human being has it) But, if all people have the potential for moral action because they are already individuals, what is the intellectual and practical value of proposing this definition of personhood as a communitarian ethical theory? Indeed, since one cannot choose not to be an individual, it cannot be a basis for human ethical choices in the world, and it cannot be affirmed or rejected that it leads humans to make ethical choices. The complex sense of personhood is the only sense of personhood that confirms the spiritual foundations of communitarianism while still having realistic ethical meaning. Finally, an individual's personhood and communitarian orientation may be gained and lost throughout their lives. In comparison to the connection between the definition of an individual (onipa1) and communitarianism, all of this suggests a more clear link between personhood and communitarianism. REFERENCES Gyekye, K. 1992. ‘Person and Community in Akan Thought’. In: Wiredu, K., Gyekye K. (eds). Person and Community: Ghanaian Philosophical Studies, I. Washington DC:The Council for Research in Values and Philosophy. pp. 101- 122 Gyekye, K. 1995. An Essay on African Philosophical Thought: The Akan Conceptual Scheme (revised edn.). Philadelphia: Temple University Press Ikuenobe, P. 2006. Philosophical Perspectives on Communalism and Morality in African Traditions. Lanham Md.: Rowman & Littlefield Mbiti, J.S. 1989. African Religions and Philosophy (2nd revised and enlarged edn.) Heinemann: New Hampshire. Nkrumah, K. 1964. Consciencism: Philosophy and Ideology for Decolonization and Development with Particular Reference to the African Revolution. London: Heinemann Senghor, L. 1964. On African Socialism. Cook, M. (trans.). New York: Praegar Menkiti, I. A. 1984. ‘Person and Community in African Traditional Thought’. In: Wright, R.A. (ed.). African Philosophy: An Introduction (3rd edn.). Lanham, Md.: University Press of Americas. pp. 171-181. Wiredu, Kwasi 1983. ‘The Akan Concept of Mind’, Ibadan Journal of Humanistic Studies 3: pp. 113-134. Metz, Thad. “Toward an African Moral Theory”. The Journal of Political Philosophy 15, 2007: 321-341. Metz, Thad. “Human Dignity, Capital Punishment and an African Moral Theory: Toward a New Philosophy of Human Rights”. Journal of Human Rights 9, 2010: 8199. Behrens, Kevin. African Philosophy, Thought and Practice and Their Contribution to Environmental Ethics. Johannesburg: University of Johannesburg, 2011. Behrens, Kevin. “Two Normative Conceptions of „Personhood‟”. Quest 25, 2013: 103-119. Submitted By: ……………………….. Baffoe Prince Submission Date: 25th March 2021.