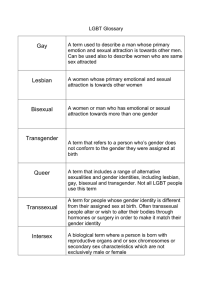

DOI: 10.1002/jclp.22687 RESEARCH ARTICLE Engaging in LGBQ+ affirmative psychotherapies with all clients: Defining themes and practices Bonnie Moradi1 | Stephanie L. Budge2 1 Department of Psychology, Center for Gender, Sexualities, and Women's Studies Research, University of Florida, Gainesville, Florida 2 Department of Counseling Psychology, University of Wisconsin‐Madison, Madison, Wisconsin Correspondence Bonnie Moradi, PhD, Department of Psychology, University of Florida, Gainesville 32611‐2250, PO Box 112250, FL. Email: moradib@ufl.edu Abstract The clinical need for lesbian, gay, bisexual, and queer (LGBQ+) affirmative psychotherapies has been widely recognized; however, empirical research on the outcomes of such psychotherapies is limited. Moreover, key questions about whom such psychotherapies are for and what they comprise require critical consideration. We begin by offering definitions to answer these questions and delineate four key themes of LGBQ+ affirmative psychotherapies. We conceptualize LGBQ+ affirmative psychotherapies not as sexual orientation group‐specific, but rather as considerations and practices that can be applied with all clients. We then summarize our own search for studies to attempt a meta‐analysis and we discuss limitations and directions for research based on our literature review. We end by delineating diversity considerations and recommending therapeutic practices for advancing LGBQ+ affirmative psychotherapy with clients of all sexual orientations. KEYWORDS cultural competence, lesbian, gay, bisexual, and queer affirmative therapy, psychotherapy, psychotherapy relationships, social justice advocacy, social justice competence 1 | INTRODUCTION The need for lesbian, gay, bisexual, and queer (LGBQ+) affirmative psychotherapies is widely recognized, though empirical research on the outcomes of such therapies is nearly nonexistent (e.g., American Psychological Association, 2012). Among the barriers that impede research on the outcomes of LGBQ+ affirmative This article is adapted, by special permission of Oxford University Press, by the same authors in J. C. Norcross & B. E. Wampold (Eds.) (2018), Psychotherapy relationships that work. volume 2 (3rd ed.). New York: Oxford University Press. The Interdivisional APA Task Force on Evidence-Based Psychotherapy Relationships and Responsiveness was cosponsored by the APA divisions of Psychotherapy (29) and Counseling Psychology (17). 2028 | © 2018 Wiley Periodicals, Inc. wileyonlinelibrary.com/journal/jclp J. Clin. Psychol. 2018;74:2028–2042. MORADI AND BUDGE | 2029 psychotherapies are complexities in defining whom LGBQ+ affirmative psychotherapies are for and what key elements these therapies comprise. Wrestling with these “who” and “what” questions is fundamental to forging best practices for LGBQ+ affirmative psychotherapies. In this article, we begin by providing definitions to answer these who and what questions, delineate four key themes of LGBQ+ affirmative psychotherapies, offer measures and assessment recommendations, and describe clinical examples. We then summarize our own search for studies to attempt a meta‐analysis and we discuss limitations and directions for research based on our literature review. We end by delineating diversity considerations and recommending therapeutic practices. 2 | DEFINITIONS A ND ME ASURES 2.1 | Sexual orientation Estimates from population‐based surveys suggest that approximately 3.5% or 8 million adults in the United States identify as LGB, 8.2% or 19 million report having engaged in same‐sex sexual behaviors, and 11% or 25.6 million report having some same‐sex attraction (Gates, 2011). Conceptualizations of sexual orientation and sexual minority status vary across cultural communities. The following definitions of key sexual orientation constructs reflect dominant US cultural discourses (e.g., American Psychological Association, 2012; Dillon, Worthington, & Moradi, 2011; Moradi, 2016). Sexual orientation reflects the sex(es) and/or gender(s) to whom a person is attracted; it includes multiple dimensions such as physical attraction, emotional attraction, and sexual behaviors which may or may not align with one another at a given time or across a person’s life. Sexual identity (or sexual orientation identity) captures a person’s identification or description of their sexual orientation to themselves and others (e.g., asexual, bisexual, gay, lesbian, queer, questionning). Sexual minority is an umbrella term that captures sexual orientations and identities that are stigmatized and oppressed in current sociopolitical systems (i.e., LGBQ+). Despite this multidimensionality, popular conceptualizations of sexual orientation and identity are often grounded in a binary view of sex collapsed with gender (i.e., female = woman, male = man). Such a view has long been critiqued by feminist scholars (e.g., Bem, 1993) who distinguished sex, or the biological and anatomical characteristics used to assign people at birth to sex categories (e.g., female, intersex, male) from gender, as the social meaning and collection of characteristics prescribed to sex categories in a given society or culture. Nevertheless, grounded in the limitations of sex and gender binaries, popular views of sexual orientation assume that a person assigned female at birth identifies as a woman and presents in feminine ways. If she is attracted to other women, she is considered and compelled to identify as lesbian; if she is attracted to other men, she is considered and compelled to identify as heterosexual or straight. Men are categorized in parallel fashion as gay or heterosexual/straight. Problematically, within these binaries, bisexual, queer, and other sexual orientations and identities are often rendered invisible or viewed as transitions toward an ultimate monosexual orientation and identity (i.e., gay/lesbian or heterosexual/straight). Best practices for assessing sexual orientation involve eschewing these binaries and assessing multiple dimensions, such as sexual orientation identity, sexual attraction, and sexual behaviors, and including open response options for people to self‐describe beyond predetermined categories (e.g., Sexual Minority Assessment Research Team [SMART], 2009). For example, intake forms can assess self‐identification with “How do you self‐ identify?” and options of bisexual, gay, heterosexual/straight, lesbian, queer, and an open response. Response options can be alphabetized to avoid conveying a hierarchy of identities. Sexual attraction can be assessed with “People vary in their sexual attraction to other people. Which best describes your attraction?” and options to assess levels of attraction to gender nonbinary people, men, women, and an open response. Sexual behavior can be assessed with “Which best describes your sexual partners?” and options to assess sexual behavior with gender nonbinary people, men, women, no sexual behavior, and an open response. In therapy sessions or intake interviews, it is important to listen carefully to clients’ self‐descriptions and the specific terms they use to refer to themselves (e.g., bisexual, lesbian, queer) and their romantic partners (e.g., 2030 | MORADI AND BUDGE partner, spouse, wife, girlfriend), and to mirror these terms. It is also helpful to check with clients in open ended ways to facilitate their personal descriptions. For example, broad questions such as “what are some important aspects of who you are?” can be a starting point for rich self‐description of personal identities. Such questions can be followed with specific questions about sexual orientation identity and romantic relationships, such as “What terms or identities do you prefer to describe your sexual orientation or romantic attractions?” or “How do you prefer to refer to your partner?” Some clients may resist such identity categories altogether (e.g., “I don’t identify with any sexual orientation label” or “my attractions are not based on gender”) and these are also self‐definitions to be respected and affirmed. Best practices for assessing sexual orientation also require disaggregating sexual orientation, sex, and gender. Assessing sex requires careful consideration to include intersex individuals. One approach is assessing sex assigned at birth with the options available on birth certificates (i.e., female and male), and using a separate question to assess whether individuals are also intersex (The GenIUSS Group, 2014). Assessment of gender identity can include categories for transwoman, transman, and nonbinary gender identities (e.g., genderqueer), and an open response option for respondents to self‐describe (The GenIUSS Group, 2014). The aforementioned in‐session recommendations for facilitating self‐descriptions also apply to assessing sex and gender. Psychotherapists can routinely assess sexual orientation, sex, and gender along with other demographics such as age, class, ethnicity, and race. 2.2 | LGBQ+ affirmative psychotherapies We favor a conceptualization of LGBQ+ affirmative psychotherapy, not as sexual orientation group‐specific, but rather as principles and practices that can be applied with all clients and ultimately, in all psychotherapies (e.g., Matthews, 2007). This inclusive position addresses important pragmatic realities. Specifically, practitioners may not be aware of clients’ LGBQ+ identities. Even if therapists routinely assess LGBQ+ identities, clients may not want to or be ready to disclose these identities, especially in early phases of psychotherapy. In fact, clients’ disclosure of LGBQ+ identities may be predicated on therapists first creating the very conditions of LGBQ+ affirmativeness to facilitate such disclosure (e.g., Dorland & Fischer, 2001). Moreover, many clients who do not identify as LGBQ+ may want (and warrant) LGBQ+ affirmative therapy (e.g., children of LGBQ+ parents). For these reasons, we endorse a conceptualization of LGBQ+ affirmative psychotherapy that acknowledges the unequal power inherent in the client‐therapist dyad, which may prove more pronounced in dyads involving LGBQ+ clients and heterosexual therapists, and that places the responsibility of providing affirmative methods on the clinician rather than on the client. Thus, we contend that the answer to the first question “whom are LGBQ+ Affirmative Psychotherapies for?” is simply, everyone. This vision does not mean that LGBQ+ affirmative psychotherapy is “generic” therapy as currently practiced. Rather, it requires elevating all psychotherapies to integrate the key themes of LGBQ+ affirmative psychotherapy. Drawing from prior conceptualizations of psychotherapy with LGBQ+ people (e.g., American Psychological Association, 2012; Fassinger, 2017; Harrison, 2000; Johnson, 2012; King, Semlyen, Killaspy, Nazareth, & Osborn, 2007), we define LGBQ+ affirmative psychotherapies as comprising four key themes: (a) counteracting anti‐LGBQ+ therapist attitudes and enacting LGBQ+ affirmative attitudes, (b) acquiring accurate knowledge about LGBQ+ people’s experiences and their heterogeneity, (c) calibrating integration of accurate knowledge about LGBQ+ people’s experiences and their heterogeneity into therapeutic actions, and (d) engaging in and affirming challenges to power inequities. Across these themes, it is important not to confuse the absence of inappropriate therapy (e.g., acting on anti‐LGBQ+ bias or inadequate knowledge) with the presence of affirmative therapy. A number of existing measures assess therapists’ or trainees’ self‐reported perceptions of their own competencies in working with LGBQ+ clients (see Table 1). Although these are not measures of LGBQ+ affirmative ingredients per se, these measures are the closest available approximations of operationalizing those ingredients. The Lesbian, Gay, and Bisexual Affirmative Counseling Self‐Efficacy Inventory (Dillon & Worthington, 2003) and its short form (Dillon et al., 2015) are among the fullest in scope, assessing the application of knowledge, therapy MORADI AND | BUDGE 2031 T A B L E 1 Measures of self‐reported LGBQ+ affirmative psychotherapy competencies Refernces Measure name Purpose Sample items Bidell (2005) Sexual Orientation Counselor Competency Scale (SOCCS) 29 items assess counselors’ attitudes, skills, and knowledge in working with LGB clients Attitudes: “The lifestyle of a LGB client is unnatural or immoral” (reversed) Skills: “I have experience counseling gay male clients” Knowledge: “Being born a heterosexual person in this society carries with it certain advantages” Burkard, Pruitt, Medler, and Stark‐Booth (2009) Lesbian, Gay, and Bisexual Working Alliance Self‐Efficacy Scales (LGB‐WASES) 32 items assess counselor‐ trainees self‐efficacy in establishing working alliance with LGB clients Emotional bond: “I can express empathy for an LGB client” Establishing tasks: “I can help LGB clients to establish social relationships in the gay community” Cultural competence: “An LGB client and I can mutually agree on an important purpose for counseling” Crisp (2006) Dillon and Worthington (2003); Dillon et al. (2015) Gay Affirmative Practice Scale (GAP) Lesbian, Gay, and Bisexual Affirmative Counseling Self‐Efficacy Inventory (LGB‐CSI), original and short form 30 items assess clinicians’ beliefs and behaviors in practice with gay and lesbian clients 32 items (original) and 15 items (short form) assess counselors’ self‐efficacy to perform LGB affirmative counseling behaviors Beliefs: “Practitioners should educate themselves about gay/lesbian lifestyles” Behaviors: “I acknowledge to clients the impact of living in a homophobic society” Application of knowledge: “Assist LGB clients to develop effective strategies to deal with heterosexism and homophobia” Relationship: “Establish a safe space for LGB couples to explore parenting” Assessment: “Assess for post‐ traumatic stress felt by LGB victims of hate crimes based on their sexual orientations/ identities” Advocacy skills: “Refer LGB clients to affirmative legal and social supports” Self‐awareness: “Identify my own feelings about my own sexual orientation and how it may influence a client” (Continues) 2032 | TABLE 1 MORADI AND BUDGE (Continued) Refernces Measure name Purpose Sample items Logie, Bridge, and Bridge (2007) LGBT Assessment Scale (LGBTAS) 26 items assess social work graduate students’ “phobias, attitudes, and cultural competence” in working with LGBT clients Phobias: “I would feel comfortable working closely with a gay man” Attitudes: “Bisexuality is merely a different kind of lifestyle that should not be condemned” Cultural competence: “I am knowledgeable about the issues and challenges facing LGBT people and feel competent in my ability to work effectively with this population” Note. LGBQ: lesbian, gay, bisexual, and queer; LGBT: lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender. relationship, assessment, advocacy skills, and self‐awareness. However, the measures outlined in Table 1 also have key limitations. Specifically, they tend to place greater emphasis on assessing anti‐LGBQ+ attitudes and feelings than on assessing LGBQ+ affirmative therapy behaviors, some use problematic language (e.g., referring to LGBQ+ identities as a lifestyle), some have psychometric limitations and gaps, and all rely on therapists’ self‐reports. None of these measures directly assesses the fourth theme of LGBQ+ affirmative psychotherapy ingredients: Engaging in and affirming challenges to power inequities. 3 | CLIN IC AL EXAMP LES Examples of how clinicians can implement LGBQ+ affirmative psychotherapies illustrate the transtheoretical, transdiagnostic, and transpopulation scope of such psychotherapies. One such example illustrates the calibrated integration of accurate knowledge. Specifically, Russell and Hawkey (2017) delineated how clinicians can integrate knowledge about anti‐LGBQ+ stigma in a “stigma‐informed” approach to psychotherapy. They emphasize the client’s appraisal of the stigma along with the use of positive coping strategies to mitigate the impact of stigma on the client. First, this approach requires that the therapist acquire accurate knowledge about the context of stigma that LGBQ+ people experience. In addition to the scholarly literature, public resources are available through national organizations such as the American Psychological Association (APA) Public Interest Directorate, APA Society for the Psychological Study of LGBT Issues, Lambda Legal, National LGBTQ Task Force, and The Williams Institute. Next, grounded in such knowledge, the therapist builds on the individualized understanding of the client to situate stigma and oppression in external contexts rather than in the client’s self‐blaming internalization. The therapist facilitates sociopolitical analysis that connects heterosexism with other systems of stigmatization and oppression (e.g., racism, sexism). Finally, the therapist promotes positive coping and support for the client; this could include the therapist and client engaging in immediate advocacy and in broader social justice activism. Such strategies could include recognizing and challenging signs of internalized stigma in oneself, drawing on social support systems and affirmative communities, and engaging in collective social and political action. Another clinical example of a stigma‐informed psychotherapy is called Effective Skills to Empower Effective Men (ESTEEM). ESTEEM is a 10‐session individual treatment designed as a transdiagnostic minority stress therapy for gay and bisexual cisgender men. Pachankis (2014) and Pachankis, Hatzenbuehler, Rendina, Safren, and Parsons (2015) developed this intervention by drawing from theory that minority stressors, including MORADI AND BUDGE | 2033 discrimination and oppression, vigilance and anticipation of stigma, self‐blaming internalization of stigma, and concealment of stigmatized identity, can tax LGBQ+ people’s mental health (Meyer, 2003). In ESTEEM, psychotherapists work with clients to (a) normalize and acknowledge the adverse impact of minority stressors, (b) facilitate emotion awareness and regulation, (c) reduce avoidance of difficult and painful emotions, (d) promote assertive communication, (e) restructure minority stress cognitions (e.g., anticipation of rejection), (f) validate clients’ strengths, (g) build support relationships, and (h) affirm healthy and rewarding expressions of sexuality. These treatment principles are posited to disrupt the pathways between minority stressors and psychological symptomatology. Across these domains, and especially with restructuring minority stress cognitions, it is important to remain grounded in the reality of clients’ experiences of minority stressors and not to minimize these experiences. Again, LGBQ+ affirmative psychotherapy involves calibrating the integration of such strategies with an individualized understanding of the client’s experiences. As a final example, Fassinger (2017) offers a clinical illustration that moves away from a preoccupation with affirming specific LGBQ+ identities to affirming the client’s transgression of restrictive sexual orientation‐ and gender‐related norms and power inequities. Fassinger described this as a transgression‐affirmative nested‐ narrative identity construction and enactment (NICE) therapy. Consider a client with whom Fassinger (2017) worked for many years. The client was a 34‐year‐old, single, professional African American woman who presented with job‐related stress and psychological symptomatology. Through the course of therapy, the client gradually discussed her attraction to women, and the implications of this for various aspects of her life such as her family, religious community, and career. There was not a single moment of sexual orientation disclosure and invocation of LGBQ+ affirmative psychotherapy behaviors. Rather, the entire process of therapy involved a feminist affirmative approach. Fassinger explained, “I provided openness, collaboration, support, education, and validation of whoever and wherever she was in her identity journey—which eventually led her to romantic relationships with women” (pp. 19–20). She also described that the therapy could have been improved by a more deliberate transgression‐ affirmative approach that involved “collaborative coconstruction of a life story needing some deconstruction‐ examination and possible reconstruction/revision” (Fassinger, 2017, p. 44). Such therapy aims to help clients build a coherent life narrative that includes their gender and sexuality, rather than focusing on a sexual orientation identity label and tailored therapy behaviors. Of paramount importance, this approach reclaims the transgression of systems of inequity (e.g., same‐sex sexual attractions) as a strength and source of power. This affirmation of clients’ transgressions of systems of inequity is a core aim of the therapy and a form of social justice activism. 4 | RES EA RC H RE VI EW To determine the feasibility of a meta‐analysis of the outcomes of LGBQ+ affirmative psychotherapies, we searched for relevant studies. We considered studies that (a) compared the outcomes of LGBQ+ tailored or affirmative psychotherapies with outcomes of another form of psychotherapy, and/or (b) compared psychotherapy outcomes for LGBQ+ people with outcomes for heterosexual people. In defining psychotherapies, we focused on treatments carried out as psychotherapy or counseling, based on psychological principles and addressing psychological symptoms (as opposed to other forms of interventions such as psychoeducation, support groups, or highly specific interventions focusing on HIV or sexual behaviors). We also focused our search on studies reported in English after 1990, given substantial historical shifts in conceptualizations and contexts for psychotherapy with LGBQ+ people. We conducted keyword searches via ProQuest’s PsycINFO. The final search combined two sets of terms to capture (a) psychotherapy trials (e.g., counseling, psychotherapy, “random* control* trial,” “therapy n5 effectiveness”) and (b) LGBQ+ populations (e.g., asexual, bisexual*, gay, homosexual*, lesbian, sexual minority, queer). For LGBQ+ populations, we used terms to capture LGBQ as well as transgender populations because studies often 2034 | MORADI AND BUDGE collapse across these groups. In addition to this search, we distributed a call for unpublished data to the following professional listserves: APA Divisions 12, 29, 17 (overall and LGBT section), 44, 35, 49, and 51, as well as POWR‐L, a feminist psychology list. 4.1 | Results As illustrated in Figure 1, the initial search on June 1, 2017 for psychotherapy trials and LGBTQ+ studies resulted in k = 2,257. The call for data to professional listservs and review of references from key articles yielded an additional three studies. After all duplicates were deleted, the search resulted in k = 2,191. All abstracts were downloaded and screened along the following categories: (a) May meet inclusion for meta‐ analysis, (b) addresses psychotherapy and LGBTQ+ people without data, (c) includes data related to psychotherapy with LGBTQ+ people, (d) addresses nonpsychotherapy interventions with LGBTQ+ people, and (e) discard. A total of 22 abstracts, including all from category (a) and potentially relevant abstracts from category (c) and (d), were retrieved for full‐text evaluation. Full‐text review revealed that these publications did not meet the meta‐analysis inclusion criteria. Specifically, these publications comprised studies that did not use a control Identification or comparison group to evaluate the psychotherapeutic intervention (k = 4), were correlational or nonempirical Records identified through database searching (k = 2,257) Additional records identified through other sources (k = 3) Screening Records after duplicates removed (k = 2,191) Records screened (k = 2,191) Eligibility Full-text articles excluded (k = 22): Full-text articles assessed for eligibility (k = 22) Included Studies included in meta-analysis (k = 0) FIGURE 1 PRISMA flow diagram • k = 4 no control or comparison to evaluate the psychotherapeutic intervention • k = 4 correlational or nonempirical • k = 3 evaluated treatments for HIV risk reduction • k = 3 included only participants with HIV+ status • k = 8 did not meet but approximated inclusion criteria (results described in review) MORADI AND | BUDGE 2035 T A B L E 2 Characteristics of eight psychotherapy studies References Purpose Sample Primary findings Fals‐Stewart, O’Farrell, and Lam (2009) Compared outcomes of individual plus couples’ therapy with outcomes of individual therapy alone Gay and lesbian people with alcohol use disorder Better drinking and relationship adjustment outcomes for those who received individual plus couples therapy than those who received individual therapy alone Mondragon, Lambert, Nielsen, and Erikson (2015) Compared outcomes of psychotherapy for clients categorized as sexual minority with clients not categorized as sexual minority University counseling and career center clients Generally no posttreatment group differences on distress Morgenstern et al. (2007) Compared outcomes of motivational interviewing (four sessions), motivational interviewing plus coping skills training (12 sessions), and declining treatment HIV‐negative MSM with alcohol use disorders Morgenstern et al. (2012) Problem drinking MSM Behavioral self‐control Compared outcomes of seeking to reduce but not quit therapy reduced problem naltrexone, behavioral drinking drinking and there was no self‐control therapy, advantage to adding naltrexone plus behavioral naltrexone self‐control therapy, and placebo Pachankis et al. (2015) Gay and bisexual cisgender Compared outcomes of Compared to the waitlist ESTEEM, a transdiagnostic men, 18–35 years old, English control condition, treatment minority stress adapted fluent, HIV‐negative status, resulted in improvements on engaging in HIV risk psychotherapy with a range of symptomatology, behaviors, experiencing outcomes of waitlist including alcohol use symptoms of depression or control group problems, depressive anxiety, not receiving regular symptoms, sexual mental health services compulsivity, condom use self‐efficacy, and anxiety Higher pretreatment distress for clients reporting distress related to sexual orientation than for control group not matched on pretreatment distress Posttreatment drinking was reduced across all conditions and there was no significant difference between treatment conditions Many improvements maintained at six‐month follow‐up Similar improvement found in pooled analyses comparing all participants pretreatment and posttreatment No treatment effects for minority stress or general risk factors (Continues) 2036 | TABLE 2 MORADI AND BUDGE (Continued) References Purpose Reback and Shoptaw (2014) Compared outcomes of Gay and bisexual men seeking tailored cognitive treatment for behavioral therapy and methamphetamine abuse tailored social support therapy in the samples from Shoptaw et al. (2005) and (2008) with outcomes of a tailored cognitive behavioral therapy plus contingency management treatment in a new sample All treatment conditions were associated with improved outcomes A few advantages in substance use outcomes for the tailored cognitive behavioral therapy A few advantages in sexual risk behavior outcomes for the tailored cognitive behavioral therapy plus contingency management Shoptaw et al. (2005) Compared outcomes of cognitive behavioral therapy, contingency management, cognitive behavioral therapy plus contingency management, and a tailored cognitive behavioral therapy that included group‐specific content for gay and bisexual men All treatments were associated with improved outcomes Shoptaw et al. (2008) Sample Gay and bisexual men seeking outpatient treatment for methamphetamine dependence Gay and bisexual men seeking Compared outcomes of treatment for any stimulant tailored cognitive and/or alcohol abuse behavioral and tailored social support substance use treatments for gay and bisexual men Primary findings A few advantages observed for treatments that included contingency management, though generally few significant differences between treatment conditions Both treatment conditions were associated with reductions in substance use and sexual risk behaviors A few advantages observed for the tailored cognitive behavioral therapy over the tailored social support therapy (k = 4), evaluated treatments for HIV risk reduction (k = 3), and included only participants with HIV+ status thereby precluding disaggregation of sexual orientation from HIV+ status (k = 3). Importantly, 16 of the 22 studies included only men; the studies generally did not specify inclusion or exclusion of transgender people, though one study specifically excluded transgender people. Eight publications came closest to the inclusion criteria, though they did not meet these criteria and were too diverse in focus and methodology for meta‐analysis. Table 2 summarizes the studies that approached our criteria and provided useful research information on the practice of LGBQ+ affirmative psychotherapy. 5 | L I M I T A T I O N S O F TH E R E S E A R C H As the present review reveals, there is a dearth of research on the outcomes of LGBQ+ affirmative psychotherapies. Fundamental to advancing research in this area is the need to move beyond sole reliance on therapists’ self‐report measures of their own attitudes and knowledge, and to design and evaluate measures of client, therapist, and observer appraisals of the presence of the key LGBQ+ affirmative themes. MORADI AND BUDGE | 2037 In addition, the implicit assumption that LGBQ+ psychotherapies are tailored specifically for LGBQ+ people and not others can be challenged. Research is needed to investigate the outcomes of LGBQ+ affirmative psychotherapies with all clients, across the spectrum of sexual orientations and identities. In such research, analyses would compare the outcomes of psychotherapies with and without LGBQ+ affirmative ingredients, though ethical practice limits experimental manipulation of some ingredients with clients (e.g., anti‐LGBQ+ attitudes). Similarly, research is needed to broaden the range of presenting problems for which (a) psychotherapies are examined with LGBQ+ populations and (b) LGBQ+ affirmative psychotherapies are examined with all populations. While sexual risk behaviors and substance abuse are important foci, there is a near exclusive focus on treatment evaluations with these presenting concerns. Research is needed to investigate the full range of psychological symptoms and life challenges (e.g., depression, body image, relationship distress, vocational issues). Moreover, the centrality of the context of oppression requires expanding the range of psychotherapy outcomes considered. Traditional conceptualizations of favorable outcomes include decreases in symptomatology and increases in psychological well‐being. However, a functional response to anti‐LGBQ+ discrimination and oppression may include increased anger, sadness, and discontent. In fact, these “symptoms” may prove indicators of the important emotional work involved in recognizing oppressive systems, taking constructive action, and developing a social justice orientation (e.g., Hercus, 1999; Moradi, 2012). Thus, such outcomes can be measured and conceptualized as favorable psychotherapy outcomes. Measures of symptom reduction can also be supplemented with measures of targeted outcomes, such as minority stressors, including anticipation of stigma, internalized prejudice, and concealment of sexual orientation (e.g., Pachankis et al., 2015). Additional outcomes could include clients’ perceptions of key mechanisms for change, engagement in everyday activism and collective action, and social justice orientation. Finally, sociodemographic and other forms of diversity among LGBQ+ populations remain underexamined in psychotherapy research. Nearly all of the studies that emerged for full‐text examination in our review focused on cisgender men, mostly recruited for HIV+ status and/or substance use problems. In these studies, the inclusion or exclusion of transgender men was generally unacknowledged or transgender men were explicitly excluded. Similarly, women (transgender inclusive) and people with nonbinary or other gender identities were not included. Psychotherapy research that includes LGBQ+ people of all genders and LGBQ+ populations beyond only those with HIV+ status and substance abuse is needed. Strategies delineated for recruiting diverse samples across age, class, gender, ethnicity, race, and other sociodemographics can be used (e.g., DeBlaere, Brewster, Sarkees, & Moradi, 2010). Beyond sociodemographic diversity, individual differences in levels of minority stressors (e.g., experiences of discrimination, internalized stigma) could interact with LGBQ+ affirmative psychotherapy ingredients to shape outcomes. Similarly, LGBQ+ affirmative psychotherapy ingredients may interact with clients’ expressed sexual orientation such that outcomes differ for LGBQ+ identified and nonidentified clients. Moderators such as sexual orientation identities and levels of minority stressors may be points for calibrating psychotherapy ingredients across clients. 6 | D IV E R S I T Y C O N S I D E R A T I O N S LGBQ+ identities are diverse, culturally situated, and dynamic, as reflected in the expanding inclusivity of sexual identity labels (e.g., L, G, B, Q). Moreover, LGBQ+ people as a group represent all ages, classes, genders, ethnicities, races, and other sociodemographic characteristics. Acknowledging this diversity among LGBQ+ populations is critical. To this end, it is helpful to distinguish strong intersectional analysis from superficial considerations of multiple/ intersecting identities that involve blanket application of group‐level information or presumed cultural characteristics to individual clients (Moradi, 2017; Moradi & Grzanka, 2017). Strong feminist intersectional analysis (e.g., Collins, 1990/2000; Crenshaw, 1989) requires understanding how multiple systems of oppression and 2038 | MORADI AND BUDGE privilege function simultaneously in clients’ lives and enacting interventions that attend to and challenge these inequities. Psychotherapy practice and research informed by intersectional analysis articulates, assesses, and analyzes the system‐level constructs (e.g., experiences of classism, heterosexism, racism, sexism) for which demographic variables are implicit proxies. Intersectional analysis may also challenge the epistemology and power inequities in how we evaluate psychotherapy outcomes (Moradi & Grzanka, 2017). This includes valuing statistical significance of outcomes along with (rather than in lieu of) clients’ experiences and the benefits of psychotherapy to clients in real‐world contexts. While RCTs are considered a gold standard, they present limitations in evaluating LGBQ+ affirmative psychotherapies. For example, LGBQ+ affirmative ingredients are to be applied across psychotherapy methods, diagnoses, and populations. This breadth can conflict with the pressures for a high degree of control in RCTs, for example, in ensuring fidelity of interventions or in defining patient populations in terms of demographics and/or diagnoses. A complementary alternative is practice‐based evidence (Barkham & Mellor‐Clark, 2000), which focuses on high‐ quality data derived from clients and practitioners in naturalistic settings with their contextual complexities intact. Indeed, data that capture rather than control the complexity of LGBQ+ people and their presenting concerns can address many of the limitations of prior research (e.g., inclusion criteria that focus narrowly on cisgender men living with HIV). Practice‐based evidence is also consistent with intersectional analysis and the defining themes of LGBQ+ affirmative psychotherapies in that it foregrounds diversity in context, clients, practitioners, and real‐world complexity as integral to evaluating psychotherapy, rather than as confounds to be controlled. 7 | THERAPEUT IC PRACTICES We conclude by advancing therapeutic practices along the four key themes of LGBQ+ affirmative psychotherapies based on the available literature. 7.1 | Counteracting anti‐LGBQ+ therapist attitudes and enacting LGBQ+ affirmative attitudes 1. Counteract biases that may pathologize and oppress LGBQ+ identities and people. Examples of such behaviors include assuming that sexual orientation is the cause of presenting concerns, avoiding or minimizing discussions of sexual orientation, overidentifying with LGBQ+ clients in ways that are defensive or objectifying (e.g., “I have a gay friend”), operating on stereotypes about LGBQ+ people or on heteronormative assumptions and biases, and enacting pathologizing assumptions that LGBQ+ people need therapy or that LGBQ+ identities are dangerous or problematic (Shelton & Delgado‐Romero, 2011). 2. Use inclusive language and clients’ preferred language. In clinical contacts and measures, until the client’s preferred terminology is assessed, use inclusive language such as “your partner or spouse” rather than language that assumes partner/spouse gender. Use of inclusive language is associated with LGB people’s positive views of therapists, greater willingness and comfort to disclose sexual orientation identity, and greater likelihood to return to psychotherapy (Dorland & Fischer, 2001). Moreover, contrary to speculation that LGBQ+ inclusive language might confuse or alienate heterosexual clients, inclusive language was unrelated to heterosexual people’s perceptions of therapist credibility and utilization intent, and was related positively to their willingness to disclose (Ross, Waehler, & Gray, 2013). In addition, pay attention to and inquire about the language clients prefer to describe themselves and their relationships (e.g., “How do you prefer to describe your sexual orientation or romantic attractions?” “How do you prefer to refer to your partner?”), and mirror clients’ preferred language. MORADI AND BUDGE | 2039 3. Demonstrate an inclusive stance in professional materials and in the therapy environment. There is evidence that LGBQ+ clients notice heteronormative bias in the therapy environment, for example, in the absence of LGBQ+ representation in displays and materials, and experience such bias as a form of subtle discrimination in therapy (Shelton & Delgado‐Romero, 2011). Examples of strategies for demonstrating an inclusive stance include assessing sexual orientation using best practices (see Section 2), and using brochures, displays, and artwork that are inclusive and affirmative of LGBQ+ people. 7.2 | Acquiring accurate knowledge about LGBQ+ people’s experiences and their heterogeneity 1. Acquire accurate knowledge about the sociopolitical oppression of LGBQ+ people and about their broader life experiences. It is important to acquire knowledge about anti‐LGBQ+ stigma, minority stress, identity formation and management (e.g., concealment and disclosure strategies and their consequences), family structures (e.g., families of choice, marriage, partnerships, consensual nonmonogomy, parenting within and outside of legal status), workplace experiences (discriminatory and antidiscrimination policies and laws, hostile or affirming careers), LGBQ+ affirmative support communities, and the heterogeneity of LGBQ+ people and their needs across dimensions of sociodemographic diversity (e.g., American Psychological Association, 2012). 2. Recognize LGBQ+ strengths and resilience that may promote well‐being and mitigate minority stress and engage these strengths in psychotherapy. LGBQ+ people describe developing a number strengths, including actively pursuing authenticity in self‐definition, developing freedom from gender‐specific roles, cultivating cognitive flexibility, and being involved in social justice activism (e.g., Brewster, Moradi, DeBlaere, & Velez, 2013; Riggle, Whitman, Olson, Rostosky, & Strong, 2008). As one example, cognitive flexibility buffered bisexual people’s mental health against experiences of antibisexual prejudice (Brewster et al., 2013). Thus, therapists can explore how LGBQ+ clients’ life experiences may foster cognitive flexibility and how this strength can be integrated in interventions to promote positive psychotherapy outcomes. 7.3 | Calibrating integration of accurate knowledge about LGBQ+ people’s experiences and their heterogeneity into therapeutic actions 1. Individualize understanding and treatment of a given client, without overemphasizing or underemphasizing the centrality of LGBQ+ status. We caution against an “apply knowledge and stir” approach in which knowledge about LGBQ+ populations is invoked uncritically with all (assumed) LGBQ+ clients. Such an approach objectifies clients as a stereotypic monolith. Instead, the integration of group‐specific knowledge can be calibrated to the experiences and needs of the specific client. Individualization of knowledge about LGBQ+ people is consistent with an “informed not‐knowing stance” (Laird, 2000) whereby the therapist expresses genuine curiosity to understand the client more deeply, rather than assume a preconceived understanding. This ability to understand the client is coupled with, and in fact predicated on, therapists taking responsibility to acquire accurate background knowledge about LGBQ+ people, rather than expecting clients to educate them. 2. Consider individual differences in how stigma and minority stressors shape clients’ lives and psychotherapy. Draw from the stigma‐informed approach to therapy (Russell & Hawkey, 2017) and the promising empirical evidence for ESTEEM (Pachankis, 2014, 2015) to assess and integrate individual differences in minority stress experiences. In these approaches, practitioners first acquire knowledge about anti‐LGBQ+ stigma and oppression, then work with clients to develop an individualized understanding of how such stigma manifests in clients’ experiences. 2040 | MORADI AND BUDGE 7.4 | Engaging in and affirming challenges to power inequities 1. Affirm clients’ challenging of power inequities and engage in such challenging outside of therapy. Consider using the transgression‐affirming NICE model (Fassinger, 2017), which emphasizes fostering an affirmative stance toward the client’s transgression of restrictive norms and power inequities. In our view, it is important to couple LGBQ+ affirmative attitudes, knowledge, and actions in the therapy room with practicing the themes of LGBQ+ affirmation in everyday actions outside of the therapy room. Drawing from Steinem’s (1983) examples of anti‐sexist “outrageous acts and everyday rebellions,” LGBQ+ affirmative actions in and outside of psychotherapy might include challenging anti‐LGBQ+ humor and discourse, displaying LGBQ+ affirming images and information in the office, using LGBQ+ inclusive language consistently, asking one’s organizations and communities about their stance and actions toward LGBQ+ people, refusing to contribute to or participate in organizations with anti‐LGBQ+ practices, or publicizing or joining local social justice efforts (e.g., bookstore, community center). 2. Engage in sociopolitical analysis as a necessary component of LGBQ+ affirmative psychotherapies, distinct from cultural tailoring. Without careful sociopolitical analysis, cultural tailoring efforts may blur into cultural stereotyping identified by LGBQ+ clients as subtle biases in psychotherapy (Shelton & Delgado‐Romero, 2011). For example, culturally tailored substance use treatments may discuss LGBQ+ bars and clubs as cultural triggers for substance abuse or draw parallels between disclosing one’s drug problems and disclosing one’s sexual identity. Instead, sociopolitical analysis in psychotherapy would situate LGBQ+ bars as outcomes of heterosexist systems that necessitate such safer social spaces, destigmatize these spaces by acknowledging that heterosexual‐dominant bars also trigger substance use, and frame coming out as an outcome of heteronormative assumptions that make it necessary for LGBQ+ people, but not heterosexual people, to constantly judge the context of anti‐LGBQ+ threat. 3. Apply LGBQ+ affirmative principles to all clients. All clients have a narrative—articulated or not—about how their life is shaped by gender, sexualities, and other sociopolitical systems; all clients’ life narratives and how they transgress systems of inequity can be examined constructively and collaboratively in therapy; and transgressions that challenge systems of inequity can be affirmed in all clients. This approach can help all clients strive for more self and collective authenticity, actualization, and equity. REFERENC ES American Psychological Association (2012). Guidelines for psychological practice with lesbian, gay, and bisexual clients. American Psychologist, 67, 10–42. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0024659 Barkham, M., & Mellor‐Clark, J. (2000). Rigour and relevance: Practice‐based evidence in the psychological therapies. In N. Rowland, & S. Goss (Eds.), Evidence‐based counselling and psychological therapies (pp. 127–144). London, England: Routledge. Bem, S. L. (1993). The lenses of gender: Transforming the debate on sexual inequality. New Haven, CT: Yale. Bidell, M. P. (2005). The Sexual Orientation Counselor Competency Scale: Assessing attitudes, skills, and knowledge of counselors working with lesbian, gay, and bisexual clients. Counselor Education and Supervision, 44, 267–279. https://doi. org/10.1002/j.1556‐6978.2005.tb01755.x Brewster, M. E., Moradi, B., DeBlaere, C., & Velez, B. L. (2013). Navigating the borderlands: The roles of minority stressors, bicultural self‐efficacy, and cognitive flexibility in the mental health of bisexual individuals. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 60, 543–556. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0033224 Burkard, A. W., Pruitt, N. T., Medler, B. R., & Stark‐Booth, A. M. (2009). Validity and reliability of the lesbian, gay, bisexual working alliance self‐efficacy scales. Training and Education in Professional Psychology, 3, 37–46. https://doi.org/10.1037/ 1931‐3918.3.1.37 Collins, P. H. (2000). Black feminist thought: Knowledge, consciousness, and the politics of empowerment. New York, NY: Routledge. (Original work published 1990) Crenshaw, K. W. (1989). Demarginalizing the intersection of race and sex: A Black feminist critique of antidiscrimination doctrine, feminist theory and antiracist politics. University of Chicago Legal Forum, 140, 139–167. MORADI AND BUDGE | 2041 Crisp, C. (2006). The Gay Affirmative Practice Scale (GAP): A new measure for assessing cultural competency with gay and lesbian clients. Social Work, 51, 115–126. https://doi.org/10.1093/sw/51.2.115 DeBlaere, C., Brewster, M. E., Sarkees, A., & Moradi, B. (2010). Conducting research with LGB people of color: Methodological challenges and strategies. The Counseling Psychologist, 38, 331–362. https://doi.org/10.1177/ 0011000009335257 Dillon, F. R., Alessi, E. J., Craig, S., Ebersole, R. C., Kumar, S. M., & Spadola, C. (2015). Development of the lesbian, gay, and bisexual affirmative counseling self‐efficacy inventory–short form (LGB‐CSI‐SF). Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity, 2(1), 86–95. https://doi.org/10.1037/sgd0000087 Dillon, F. R., & Worthington, R. L. (2003). The lesbian, gay, and bisexual affirmative counseling self‐efficacy inventory (LGB‐CSI): Development, validation, and training implications. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 50, 235–251. https://doi. org/10.1037/0022‐0167.50.2.235 Dillon, F. R., Worthington, R. L., & Moradi, B. (2011). Sexual identity as a universal process. In S. J. Schwartz, K. Luyckx, & V. L. Vignoles (Eds.), Handbook of identity theory and research (Vols 1 and 2, pp. 649–670). New York, NY: Springer. Dorland, J. M., & Fischer, A. R. (2001). Gay, lesbian, and bisexual individuals’ perceptions: An analogue study. The Counseling Psychologist, 29, 532–547. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011000001294004 Fals‐Stewart, W., O’Farrell, T. J., & Lam, W. K. K. (2009). Behavioral couple therapy for gay and lesbian couples with alcohol use disorders. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 37, 379–387. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsat.2009.05.001 Fassinger, R. E. (2017). Considering constructions: A new model of affirmative therapy. In K. A. DeBord, A. R. Fischer, K. J. Bieschke, & R. M. Perez (Eds.), Handbook of sexual orientation and gender diversity in counseling and psychotherapy (pp. 19– 50). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. Gates, G. J. (2011). How many people are lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender? Los Angeles, CA: Williams Institute. Harrison, N. (2000). Gay affirmative therapy: A critical analysis of the literature. British Journal of Guidance and Counselling, 28, 37–53. https://doi.org/10.1080/030698800109600 Hercus, C. (1999). Identity, emotion, and feminist collective action. Gender and Society, 13, 34–55. https://doi.org/10.1177/ 089124399013001003 Johnson, S. D. (2012). Gay affirmative psychotherapy with lesbian, gay, and bisexual individuals: Implications for contemporary psychotherapy research. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 82, 516–522. https://doi.org/10.1111/j. 1939‐0025.2012.01180.x King, M., Semlyen, J., Killaspy, H., Nazareth, I., & Osborn, D. (2007). A systematic review of research on counseling and psychotherapy for lesbian, gay, bisexual & transgender people. Lutterworth, Leicestershire: British Association for Counseling and Psychotherapy. Retrieved from https://www.peter‐ould.net/wp‐content/uploads/king‐systematic‐ review‐1.pdf Laird, J. (2000). Theorizing culture: Narrative ideas and practice principles. Journal of Feminist Family Therapy, 11, 99–114. https://doi.org/10.1300/J086v11n04_08 Logie, C., Bridge, T. J., & Bridge, P. D. (2007). Evaluating the phobias, attitudes, and cultural competence of Master of Social Work students toward the LGBT populations. Journal of Homosexuality, 53, 201–221. https://doi.org/10.1080/ 00918360802103472 Matthews, C. R. (2007). Affirmative lesbian, gay, and bisexual counseling with all clients. In K. J. Bieschke, R. M. Perez, & K. A. DeBord (Eds.), Handbook of counseling and psychotherapy with lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender clients (2nd ed, pp. 201–219). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. Meyer, I. H. (2003). Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: Conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychological Bulletin, 129, 674–697. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033‐2909.129.5.674 Mondragon, S. A., Lambert, M. J., Nielsen, S. L., & Erikson, D. (2015). Comparative psychotherapy outcomes of sexual minority clients and controls. International Journal of Education & Social Science, 2(4), 14–30. Retrieved from http://www. ijessnet.com Moradi, B. (2012). Feminist social justice orientation: An indicator of optimal functioning? The Counseling Psychologist, 40, 1133–1148. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011000012439612 Moradi, B. (2016). Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender issues. In H. S. Friedman (Ed.), Encyclopedia of Mental Health (2nd ed., Vol. 3, pp. 19–24). Oxford, England: Elsevier. Moradi, B. (2017). (Re)focusing intersectionality in psychology: From social identities back to systems of oppression and privilege. In K. DeBord, R. M. Perez, A. R. Fischer, & K. J. Bieschke (Eds.), The handbook of sexual orientation and gender diversity in counseling and psychotherapy (3rd ed., pp. 105–127). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. Moradi, B., & Grzanka, P. R. (2017). Using intersectionality responsibly: Toward critical epistemology, structural analysis, and social justice activism. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 64, 500–513. https://doi.org/10.1037/cou0000203 Morgenstern, J., Irwin, T. W., Wainberg, M. L., Parsons, J. T., Muench, F., Bux, D. A., … Schulz‐Heik, J. (2007). A randomized controlled trial of goal choice interventions for alcohol use disorders among men who have sex with men. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 75, 72–84. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022‐006X.75.1.72 2042 | MORADI AND BUDGE Morgenstern, J., Kuerbis, A. N., Chen, A. C., Kahler, C. W., Bux, D. A., & Kranzler, H. R. (2012). A randomized clinical trial of naltrexone and behavioral therapy for problem drinking men who have sex with men. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 80, 863–875. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0028615 Pachankis, J. E. (2014). Uncovering clinical principles and techniques to address minority stress, mental health, and related health risks among gay and bisexual men. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 21, 313–330. https://doi.org/10.1111/ cpsp.12078 Pachankis, J. E. (2015). A transdiagnostic minority stress treatment approach for gay and bisexual men’s syndemic health conditions. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 44, 1843–1860. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508‐015‐0480‐x Pachankis, J. E., Hatzenbuehler, M. L., Rendina, H. J., Safren, S. A., & Parsons, J. T. (2015). LGB‐affirmative cognitive‐ behavioral therapy for young adult gay and bisexual men: A randomized controlled trial of a transdiagnostic minority stress approach. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 83, 875–889. https://doi.org/10.1037/ccp0000037 Reback, C. J., & Shoptaw, S. (2014). Development of an evidence‐based, gay‐specific cognitive behavioral therapy intervention for methamphetamine‐abusing gay and bisexual men. Addictive Behaviors, 39, 1286–1291. https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.addbeh.2011.11.029 Riggle, E. D. B., Whitman, J. S., Olson, A., Rostosky, S. S., & Strong, S. (2008). The positive aspects of being a lesbian or gay man. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 39, 210–217. https://doi.org/10.1037/0735‐7028.39.2.210 Ross, A. D., Waehler, C. A., & Gray, T. N. (2013). Heterosexual persons’ perceptions regarding language use in counseling: Extending Dorland and Fischer (2001). The Counseling Psychologist, 41, 918–930. Russell, G. M., & Hawkey, C. G. (2017). Context, stigma, and therapeutic practice. In K. A. DeBord, A. R. Fischer, K. J. Bieschke, & R. M. Perez (Eds.), Handbook of sexual orientation and gender diversity in counseling and psychotherapy (pp. 75104). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. Shelton, K., & Delgado‐Romero, E. A. (2011). Sexual orientation microaggressions: The experience of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and queer clients in psychotherapy. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 58, 210–221. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0022251 Shoptaw, S., Reback, C. J., Larkins, S., Wang, P. C., Rotheram‐Fuller, E., Dang, J., & Yang, X. (2008). Outcomes using two tailored behavioral treatments for substance abuse in urban gay and bisexual men. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 35, 285–293. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsat.2007.11.004 Shoptaw, S., Reback, C. J., Peck, J. A., Yang, X., Rotheram‐Fuller, E., Larkins, S., … Hucks‐Ortiz, C. (2005). Behavioral treatment approaches for methamphetamine dependence and HIV‐related sexual risk behaviors among urban gay and bisexual men. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 78, 125–134. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2004.10.004 SMART Sexual Minority Assessment Research Team (SMART) (2009). Best practices for asking questions about sexual orientation on surveys. Los Angeles, CA: The Williams Institute. Steinem, G. (1983). Far from the opposite shore. In Outrageous acts and everyday rebellions (pp. 341–362). The GenIUSS Group (2014). Best practices for asking questions to identify transgender and other gender minority respondents on population‐based surveys. J. L. Herman (Ed.). Los Angeles, CA: The Williams Institute. How to cite this article: Moradi B, Budge SL. Engaging in LGBQ+ affirmative psychotherapies with all clients: Defining themes and practices. J. Clin. Psychol. 2018;74:2028–2042. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.22687