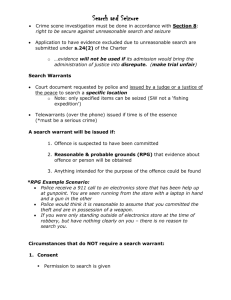

Search and Seizure Clause 1 Katz v. U.S., 389 U.S. 347 (1967) Topic: Meaning of Search Facts: The petitioner was convicted under eight-count indictment charging him with transmitting wagering information by telephone. The FBI agents intercepted his conversation with someone on a public telephone booth by placing a listening device. The recording obtained was used as evidence against him. The court of appeals rejected the contention that the recording was obtained in violation of the provisions of the Fourth Amendment of the Constitution against unreasonable searches and seizures. Issue: Whether the Fourth Amendment of the Constitution protects telephone conversations conducted in a phone booth and secretly recorded from introduction as evidence against a person? Held: The correct solution is not necessarily promoted by incantation of the phrase 'constitutionally protected area. But because of the misleading way the issues have been formulated by the petitioner, the parties have attached great significance to the characterization of the telephone booth from which the petitioner placed his calls. The court proceeded to rule that though the phone booth is a public area, as long as the person did not intend to broadcast his conversation to the world, he is protected of the provisions of the Fourth amendment. For what is protected are persons, not places. Second, the government contention that there was no violation because there was no physical intrusion of the area is not correct. If that’s the case the provisions will be limited only to searches and seizures of tangible property. In effect, the premise that property interests control the right of the Government to search and seize has been discredited. It has been said that the Fourth Amendment protects people and not simply 'areas'—against unreasonable searches and seizures hence it becomes clear that the reach of that Amendment cannot turn upon the presence or absence of a physical intrusion into any given enclosure. The Government's activities in electronically listening to and recording the petitioner's words violated the privacy upon which he justifiably relied while using the telephone booth and thus constituted a 'search and seizure' within the meaning of the Fourth Amendment. The court held that the Fourth Amendment governs not only the seizure of tangible items, but extends as well to the recording of oral statements overheard without any 'technical trespass’. Dissent. Justice Hugo Black (“J. Black”) filed a dissenting opinion. J. Black observed that eavesdropping was an ancient practice that the Framers were certainly aware of when they drafted the United States Constitution (“Constitution”). Had they wished to prohibit this activity under the Fourth Amendment of the Constitution they would have added such language that would have effectively done so. By clever wording, the Supreme Court finds it plausible to argue that language aimed specifically at searches and seizures of things that can be searched and seized may, to protect privacy, be applied to eavesdropped evidence of conversations. Concurrence. Justice John Harlan (“J. Harlan”) filed a dissenting opinion. The Fourth Amendment of the Constitution protects persons, not places. There is a twofold requirement for what protection is afforded to those people. First, that a person has exhibited an actual expectation of privacy and, second, that the expectation be one that society is prepared to recognize as reasonable. The critical fact in this case is that a person who enters a telephone booth shuts the door behind him, pays the toll, and is surely entitled to assume that his conversation is not being intercepted. On the other hand, conversations out in the open public would not be protected against being overheard as the expectation of privacy would not be reasonable. Discussion. The Fourth Amendment of the Constitution provides constitutional protection to individuals and not to particular places. The two-part test for this protection is introduced by J. Harlan. First, the person must have exhibited an actual expectation of privacy and, second, that expectation must be reasonable. People vs. Tuan Topic: Particularity of Description Facts: The RTC convicted Estela Tuan guilty of illegal possession of marijuana in illegal possession of firearms. The Court of Appeals, however, modified the appealed RTC judgment by acquitting accusedappellant of the charge for illegal possession of firearm. The Court of Appeals gave due course to accusedappellant’s Partial Notice of Appeal and accordingly forwarded the records of the case to the Supreme Court. SC then issued a resolution directing the parties to file their respective supplemental briefs. Accused-appellant raised three assignment of errors in her Brief but for the purposes of this discussion, we will only look into one and that is: Issue: Whether or not the trial court erred in not considering as void the search warrant issued against the accused-appellant. Held: The validity of the issuance of a search warrant rests upon the following factors: (1) it must be issued upon probable cause; (2) the probable cause must be determined by the judge himself and not by the applicant or any other person; (3) in the determination of probable cause, the judge must examine, under oath or affirmation, the complainant and such witnesses as the latter may produce; and (4) the warrant issued must particularly describe the place to be searched and persons or things to be seized. There is no dispute herein that the second and third factors for a validly issued search warrant were complied with because there was personal determination of probable cause by Judge Cortes and examination, under oath or affirmation, of the informants, by Judge Cortes. What is left for the Court to determine is compliance with the first and fourth factors, i.e., existence of probable cause; and particular description of the place to be searched and things to be seized. A magistrate’s determination of probable cause for the issuance of a search warrant is paid great deference by a reviewing court, as long as there was substantial basis for that determination. Substantial basis means that the questions of the examining judge brought out such facts and circumstances as would lead a reasonably discreet and prudent man to believe that an offense has been committed, and the objects in connection with the offense sought to be seized are in the place sought to be searched. Such substantial basis exists in this case. The highlight of this case for purposes of the topic to be discussed is the last requisite of a valid search warrant particular description of the place to be searched and things to be seized. Accused-appellant’s assertion that the Search Warrant did not describe with particularity the place to be searched is not correct. A description of the place to be searched is sufficient if the officer serving the warrant can, with reasonable effort, ascertain and identify the place intended and distinguish it from other places in the community. A designation or description that points out the place to be searched to the exclusion of all others, and on inquiry unerringly leads the peace officers to it, satisfies the constitutional requirement of definiteness. In the case at bar, the address and description of the place to be searched in the Search Warrant was specific enough. There was only one house located at the stated address, which was accused-appellant’s residence, consisting of a structure with two floors and composed of several rooms. Malacat v. CA Topic: Search incident to a lawful arrest Touch on: Stop and Frisk Facts: According to the arresting officers, two groups of Muslim-looking men were posted at opposite sides of Quezon Blvd. The men were “acting suspiciously with ‘their eyes moving very fast.’” When the police approached one group, the latter fled into different directions. Upon catching up with them and conducting a search, they found a grenade tucked in Malacat’s waistline. Seven days before the incident, bomb threats were reported. The trial court upheld the search and seizure as a valid “stop-and-frisk” procedure and convicted the petitioner. Issue: Is the trial court correct? Held: The general rule as regards arrests, searches and seizures is that a warrant is needed in order to validly effect the same. The Constitutional prohibition against unreasonable arrests, searches and seizures refers to those effected without a validly issued warrant, subject to certain exceptions. A warrantless arrest may be done "in flagrante delicto," (the person to be arrested has committed, is actually committing, or is attempting to commit an offense) and in "hot pursuit” (an offense has in fact just been committed, and he has personal knowledge of facts indicating that the person to be arrested has committed it). The court held that there can be no warrantless arrest surrounding the circumstances of this case. There could have been no valid in flagrante delicto or hot pursuit arrest preceding the search in light of the lack of personal knowledge on the part of Yu, the arresting officer, or an overt physical act, on the part of petitioner, indicating that a crime had just been committed, was being committed or was going to be committed. Turning to valid warrantless searches, they are limited to the following: (1) customs searches; (2) search of moving vehicles; (3) seizure of evidence in plain view; (4) consent searches; (5) a search incidental to a lawful arrest; and (6) a "stop and frisk." The trial court confused the concepts of a "stop-and-frisk" and of a search incidental to a lawful arrest In a search incidental to a lawful arrest the precedent arrest determines the validity of the incidental search. In this instance, the law requires that there first be a lawful arrest before a search can be made — the process cannot be reversed. Assuming a valid arrest, the arresting officer may search the person of the arrestee and the area within which the latter may reach for a weapon or for evidence to destroy, and seize any money or property found which was used in the commission of the crime, or the fruit of the crime, or that which may be used as evidence, or which might furnish the arrestee with the means of escaping or committing violence. Since the warrantless arrest is invalid in this case, plainly, the search conducted on petitioner could not have been one incidental to a lawful arrest. Moving on to the concept of "stop-and-frisk” . Justification for and allowable scope of a "stop-and-frisk" as a "limited protective search of outer clothing for weapons is where a police officer observes unusual conduct which leads him reasonably to conclude in light of his experience that there is criminal activity and that the persons with whom he is dealing may be armed and presently dangerous, where in the course of investigating this behavior he identifies himself as a policeman and makes reasonable inquiries, and where nothing in the initial stages of the encounter serves to dispel his reasonable fear for his own or others’ safety, he is entitled for the protection of himself and others in the area to conduct a carefully limited search of the outer clothing of such persons in an attempt to discover weapons which might be used to assault him. Probable cause is not required to conduct a "stop and frisk," nevertheless mere suspicion or a hunch will not validate a "stop and frisk." A genuine reason must exist, in light of the police officer’s experience and surrounding conditions, to warrant the belief that the person detained has weapons concealed about him. SC held the “stop and frisk” as invalid in this case for three reasons. First, it is doubtful as to Yu’s claim that petitioner was a member of the group which attempted to bomb Plaza Miranda two days earlier. This claim is neither supported by any police report or record nor corroborated by any other police officer who allegedly chased that group. There is no genuine reason existed so as to arrest and search petitioner. Second, there was nothing in petitioner’s behavior or conduct which could have reasonably elicited even mere suspicion other than that his eyes were "moving very fast". This observation is skeptical since Yu and his teammates were nowhere near petitioner and it was already 6:30 p.m., thus presumably dusk. Petitioner and his companions were merely standing at the corner and were not creating any commotion or trouble. Third, there was at all no ground, probable or otherwise, to believe that petitioner was armed with a deadly weapon. None was visible to Yu, for as he admitted, the alleged grenade was "discovered" "inside the front waistline" of petitioner, and from all indications as to the distance between Yu and petitioner, any telltale bulge, assuming that petitioner was indeed hiding a grenade, could not have been visible to Yu. In fact, as noted by the trial court when the policemen approached the accused and his companions, they were not yet aware that a hand grenade was tucked inside his waistline. They did not see any bulging object in his person. Therefore, the decision of the trail court was reversed by the SC. People v. Malmstedt Topic: Warrantless search during “on-the-spot apprehensions” with probable cause Facts: Malmstedt, a Swedish national, was travelling back from Sagada on board a bus when the vehicle was stopped by NARCOM agents. Said agents noticed a bulge on his waist (which they thought to be a gun but turned out to be a pouch bag) and asked him to produce his passport, which he refused. The agents compelled him to surrender his pouch bag, which contained hashish (a drug made by compressing and processing trichomes of the cannabis plant). More drugs were found in his traveling bags. He was then arrested and brought to headquarters. A few hours before the arrest, NARCOM received a tip that a Caucasian would be transporting drugs from Sagada. Issue: Is the search valid? Held. Yes. Search incidental to lawful warrantless arrests, exception to warrant rule. The general rule is a search, to be valid, must be supported by a search warrant. However, “where the search is made pursuant to a lawful arrest, there is no need to obtain a search warrant.” The accused was search while transporting drugs. Hence, a crime was being committed and he was caught in flagrante delicto. The case falls within the exceptions. Faced with on-the-spot information, the officers did not have time to obtain a warrant. The accused’s suspicious failure to produce his passport gave the authorities probable cause which justified the warrantless searches made on the personal effects of the accused. People v Lacerna Topic: Consented warrantless arrest Facts: Noriel and Marlon Lacerna were inside a taxi when the group of police officers signaled the taxi driver to park by the side of the road in lieu of a police checkpoint. P03 Valenzuela asked permission to search the vehicle. The officers went about searching the luggage in the vehicle. They found 18 blocks wrapped in newspaper with a distinct smell of marijuana emanating from it. When the package was opened, P03 Valenzuela saw dried marijuana leaves. According to Noriel and Marlon, the bag was a “padala” of their uncle. Marlon admitted that he was the one who gave the 18 bundle blocks of marijuana to his cousin Noriel as the latter seated at rear of the taxi with it. He however denied knowledge of the contents of the package. Marlon was charged before the RTC for “giving away” marijuana to another. Noriel on the other hand was acquitted for insufficiency of evidence. The court noticed that Noriel manifested “probinsyano” traits and was, thus, unlikely to have dealt in prohibited drugs. Marlon objected on the RTC’s decision, stating that the lower court erred in saying that the act of “giving away to another” is not defined under R.A. 6425 or the Dangerous Drugs Act. He also said that he was not aware of the contents of the plastic bag given to him by his uncle. Marlon also raised that his right against warrantless arrest and seizure was violated. Issue: Was there a violation of Marlon’s right against warrantless arrest and seizure? Held: It is mandated in the constitution that no person must be reasonably searched without a valid search warrant and any evidence obtained in violation of this shall be inadmissible for any purpose in any proceeding. However, this prohibition is subject to legal exceptions. The Rules of Court provides that a person lawfully arrested may be searched for dangerous weapons or anything which may be used as proof of the commission of an offense, without a search warrant. Five generally accepted exceptions to the rule against warrantless arrest have also been judicially formulated as follows: (1) search incidental to a lawful arrest, (2) search of moving vehicles, (3) seizure in plain view, (4) customs searches, and (5) waiver by the accused themselves of their right against unreasonable search and seizure. Search and seizure relevant to moving vehicles are allowed in recognition of the impracticability of securing a warrant under said circumstances. In such cases however, the search and seizure may be made only upon probable cause, a belief reasonably arising out of circumstances known to the seizing officer that an automobile or other vehicle contains an item, article or object which by law is subject to seizure and destruction. In the case at bar, the taxicab occupied by appellant was validly stopped at the police checkpoint by PO3 Valenzuela. It should be stressed as a caveat that the search which is normally permissible in this instance is limited to routine checks -- visual inspection or flashing a light inside the car, without the occupants being subjected to physical or body searches. A search of the luggage inside the vehicle would require the existence of probable cause. In the case at hand, however, probable cause is not evident. Nonetheless, we hold that appellant and his baggage were validly searched, not because he was caught in flagrante delicto, but because he freely consented to the search. True, appellant and his companion were stopped by PO3 Valenzuela on mere suspicion and not probable cause but Valenzuela expressly sought appellant’s permission for the search. Only after appellant agreed to have his person and baggage checked did the actual search commence. It was his consent which validated the search, waiver being a generally recognized exception to the rule against warrantless search. Roberts v. CA Facts: This case involves the prosecution of petitioners Roberts, et al., corporate officers and members of the Board of Directors of [the former] Pepsi Cola Products Phils., Inc. in connection with the company promotion called “Number Fever.” The private complainants were handlers of the supposedly winning “349” Pepsi crowns. The cases filed against petitioners were (1) estafa under Article 318 of the Revised Penal Code; (2) violation of R.A. No. 7394, (The Consumer Act of the Philippines); (3) violation of E.O. No. 913 (Strengthening the Rule-Making and Adjudicatory Powers of the Minister of Trade and Industry in order to further Protect Consumers); and (d) violation of Act No. 2333 (An Act Relative to Untrue, Deceptive and Misleading Advertisements, as amended). Probable cause was however found by the investigating prosecutor only for the crime of estafa, but not for the other alleged offenses. Petitioners Roberts, et al. filed a petition for review to the Secretary of Justice seeking the reversal of the finding of probable cause by the investigating prosecutor. They also moved for the suspension of the proceedings and the holding in abeyance of the issuance of warrants of arrest against them. Petitioners went to the Court of Appeals (CA), arguing that the respondent judge had not the slightest basis at all for determining probable cause when he ordered the issuance of warrants of arrest. The CA ruled that the Joint Resolution “was sufficient in itself to have been relied upon by respondent Judge in convincing himself that probable cause indeed exists for the purpose of issuing the corresponding warrants of arrest” and that the “mere silence of the records or the absence of any express declaration” in the questioned order as to the basis of such finding does not give rise to an adverse inference, for the respondent Judge enjoys in his favor the presumption of regularity in the performance of his official duty. Roberts, et al. sought reconsideration from the CA, but while this was pending before the CA, the Secretary of Justice affirmed the finding of probable cause by the investigating prosecutor. The CA therefore dismissed the petition for mootness. Issue: May the Supreme Court determine in this [sic] proceedings the existence of probable cause either for the issuance of warrants of arrest against the petitioners or for their prosecution for the crime of estafa?