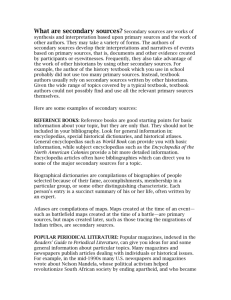

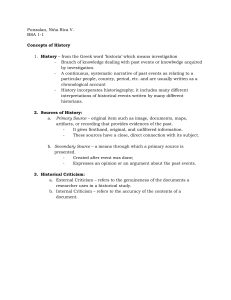

PRIMARY AND SECONDARY SOURCES Primary Sources What is a primary source? Primary sources are materials directly related to a topic by time or participation. These materials include letters, speeches, diaries, newspaper articles from the time, oral history interviews, documents, photographs, artifacts, or anything else that provides first hand accounts about a person or event. Some materials might be considered primary sources for one topic but not for another. For example, an article about the Japanese bombing in Pearl Harbor written in December 1941 written by a participant or eyewitness of the event would be a primary source; an article about the same event written in June 2017 probably was not written by an eyewitness or participant cannot be considered a primary source. Similarly, an article about the execution of Jose Rizal written by an eyewitness of the event is a primary source, but an article about the 120 anniversary of Jose Rizal’s execution written by a contemporary historian is not a primary source for the event. If, however, the topic was how Filipinos commemorate the event, then the 120th anniversary article would be a primary source for that topic. If there's any doubt about whether a source should be listed as primary or secondary, there should be an explanation annotated in the bibliography about the categorization. th Researchers usually consider the following locations when looking for primary source material: Public and College Libraries National Local Historical Societies Museums National Archives City/Town Hall Records City Planning Offices Schools Churches Community Residents Secondary Sources What are secondary sources? Secondary sources are works of synthesis and interpretation based upon primary sources and the work of other authors. They may take a variety of forms. The authors of secondary sources develop their interpretations and narratives of events based on primary sources, that is, documents and other evidence created by participants or eyewitnesses. Frequently, they also take advantage of the work of other historians by using other secondary sources. For example, the author of the history textbook which you use in school probably did not use too many primary sources. Instead, textbook authors usually rely on secondary sources written by other historians. Given the wide range of topics covered by a typical textbook, textbook authors could not possibly find and use all the relevant primary sources themselves. Examples of secondary sources: Reference books Reference books are good sources of basic information for a research. They are not necessarily included in the bibliography. Encyclopedias, special historical dictionaries, and historical atlases provides general information. Subject encyclopedias such as the Encyclopedia of World War II provide a bit more detailed information. Encyclopedia articles often have bibliographies which can direct you to some of the major secondary sources for a topic. Biographical dictionaries are compilations of biographies of people selected because of their fame, accomplishments, membership in a particular group, or some other distinguishing characteristic. Each person's entry is a succinct summary of his or her life, often written by an expert. Atlases are compilations of maps. Maps created at the time of an event—such as battlefield maps created at the time of a battle—are primary sources, but maps created later, such as those tracing the migrations of Indian tribes, are secondary sources. Popular Periodical Literature Popular magazines, indexed in the Readers' Guide to Periodical Literature provide ideas for and some general information about particular topics. Many magazines and newspapers publish articles dealing with individuals or historical issues. For example, in the late 1980s many newspapers and magazines wrote about Corazon Aquino, was the most prominent figure of the 1986 People Power Revolution, which toppled the 21-year authoritarian rule of President Ferdinand E. Marcos and restored democracy to the Philippines. History Textbooks Textbooks can be great materials to get ideas and find out about the general context of a given topic. If the topic for example is about the invention of the telescope as it revolutionized astronomy, it is essential to do some background reading on the scientific revolution as a whole, perhaps in a general textbook on European history. This gives a better understanding on how the topic fits in with the "big picture." General Historical Works and Monographs: Researchers can move from general to specific. A book on Comfort Women during the Japanese Occupation the Philippines will provide more details than a general text on World War II. A keyword search at a larger library can led to dozens, if not hundreds, of books and journals. Another way to find secondary sources is to check the notes and bibliographies of books that are already found. It is possible to find an entire book which is a bibliography of a topic; these books will be in the reference section, especially at university libraries. Monographs are full-length books dealing with a relatively narrow topic and typically are intended for people with some background in the subject. Monographs typically rely on primary sources and are well-documented, with numerous citations. Journal Articles: Historians don't always write books. Smaller essays on specific topics can be found in scholarly journals. These are periodicals similar to magazines, only they are specifically focused on history topics. Academic journals can usually be found at college and university libraries, and there are often indexes that provide links to find an article on a specific topic. Choosing Reliable Sources Historical source material consists of primary and secondary sources. Historians carefully select the events and people that they consider important. Choosing reliable sources is an important role of historical research, in order to create reliable narratives about the past. Any source material collected should be subjected to both external and internal criticism. External Criticism The authenticity of the evidence is determined by external criticism. The researcher checks the genuineness or validity of the source. The following questions fall under External Criticism: 1. Is the source really what it appears or claims to be? 2. Is it admissible as evidence? Internal Criticism The credibility of the source is established by internal criticism. The use of external criticism involves establishing whether a document can be traced back to the purported originator, establishing whether it is consistent with known facts, and studying the form of the document. Internal criticism consists of trying to establish the author’s meaning and making a judgement as to the intentions and prejudices of the writer. Internal Criticism primarily asks the following questions: 1. Is the source accurate? 2. Was the writer or creator competent, honest, and unbiased? 3. How long after the event happened until it was reported? Does the witness agree with other witnesses?