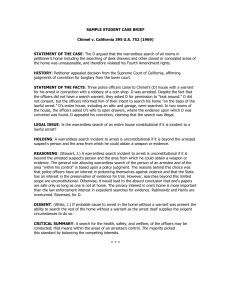

Warrantless Arrests & Drug Offenses: Case Analysis

advertisement

SIMEON LAPI Y MAHIPUS v. PEOPLE, GR No. 210731, 2019-02-13 Facts: The trial court found Simeon M. Lapi (Lapi) guilty beyond reasonable doubt of having violated Article II, Section 15 of Republic Act No. 9165 In an Information dated April 20, 2006, Lapi, Allen Sacare (Sacare), and Kenneth Lim (Lim) were charged with violation of Article II, Section 15 of Republic Act No. 9165. T On arraignment, Lapi, Sacare, and Lim pleaded not guilty to the crime charged. At pretrial, Sacare and Lim changed their pleas to guilty, and were sentenced to rehabilitation for six (6) months at a government-recognized center. Only Lapi was subjected to trial on the merits. According to the prosecution, at around 1:50 p.m. on April 17, 2006, operatives of the Bacolod City Anti-Illegal Drug Special Operation Task Group conducted a stake-out operation in Purok Sigay, Barangay 2, Bacolod City. During the operation, Police Officer 2 Ronald Villeran (PO2 Villeran) heard noises from one (1) of the houses. He "peeped through its window"[8] and saw Lapi, Sacare, and Lim "having a pot session." PO2 Villeran tried to enter the house through the main door, but the door was locked. He then tried to enter through the kitchen door. Upon entry, he met someone trying to flee, but PO2 Villeran restrained the person. Then, PO2 Villeran "peeked into the adjacent room"[11] and saw that the pot session was ongoing. He entered the room and introduced himself as a police officer. Lapi, Sacare, and Lim tried to escape, but were caught b PO2 Villeran's team members, who were waiting by the main door. the Regional Trial Court found Lapi guilty. It ruled that the warrantless arrest against him was legal since he was caught in flagrante delicto. Lapi appealed to the Court of Appeals. the Court of Appeals denied the Appeal and affirmed the Regional Trial Court Decision The Court of Appeals ruled that PO2 Villeran, upon seeing the pot session, "had reasonable ground to believe that [Lapi was] under the influence of dangerous drugs. Thus, he was justified and even obligated by law to subject him to drug screening laboratory examination." Lapi filed a Motion for Reconsideration,[24] but it was denied by the Court of Appeals Petitioner asserts that while he failed to question the validity of his arrest before entering his plea, his warrantless arrest was illegal from the start. Hence, any evidence obtained cannot be used against him. He argues that PO2 Villeran committed "a malevolent intrusion of privacy"[28] when he peeped through the window; had he not done so, he would not see what the people in the house did.[29] He contends that this intrusion into his privacy "cannot be equated in plain view[;] therefore[,] petitioner cannot be considered caught in flagrante delicto."[30] He submits that to "rule otherwise would be like giving authority to every police officer to intrude into the private homes of anyone in order to catch suspended drug offenders." Respondent,... asserts that the warrantless arrest was valid, as "[t]he act of having a pot session is clearly the overt act required under the law, which indicates that petitioner is actually committing an offense."[33] It argues that what prompted PO2 Villeran to enter the house was not the noise from one (1) of the houses, but what he saw petitioner and his companions were doing in the house where they were apprehended. Further, respondent claims that since petitioner was not the owner of that house, he had no "reasonable expectation of privacy that must be upheld."[35] It submits that "[a] houseguest who was merely present in the house with the consent of the householder cannot claim a reasonable expectation of privacy in his host's home." Issues: This Court is asked to resolve the Issue of whether or not the warrantless arrest against petitioner Simeon M. Lapi was valid. Ruling: The Constitution guarantees against "unreasonable" warrantless searches and seizures. This presupposes that the State may do so as long as they are reasonable. People v. Aruta[49] outlines the situations where a warrantless search and seizure may be declared valid:Warrantless search incidental to a lawful arrest recognized under Section 12, Rule 126 of the Rules of Court and by prevailing jurisprudence;Seizure of evidence in "plain view," the elements of which are: (a) a prior valid intrusion based on the valid warrantless arrest in which the police are legally present in the pursuit of their official duties; (b) the evidence was inadvertently discovered by the police who had the right to be where they are; (c) the evidence must be immediately apparent[;] and (d) "plain view" justified mere seizure of evidence without further search;Search of a moving vehicle. Highly regulated by the government, the vehicle's inherent mobility reduces expectation of privacy especially when its transit in public thoroughfares furnishes a highly reasonable suspicion amounting to probable cause that the occupant committed a criminal activity;Consented warrantless search;Customs search;Stop and Frisk; andExigent and Emergency Circumstances. Here, petitioner was seen by police officers participating in a "pot session." Here, however, petitioner admits that he failed to question the validity of his arrest before arraignment.[56] He did not move to quash the Information against him before entering his plea.[57] He was assisted by counsel when he entered his plea.[58] Likewise, he was able to present his evidence. What he questions is the alleged illegality of his arrest.Petitioner, however, has already waived the right to question the validity of his arrest. No items were seized from him during his arrest as he was not charged with possession or sale of illegal drugs. Thus the trial court and the Court of Appeals did not err in finding him guilty beyond reasonable doubt in violation of Article II, Section 15 of Republic Act No. 9165. MARIO VERIDIANO vs. PEOPLE G.R. No. 200370 June 7, 2017 (warrantless searches, requisites) Facts: 1.) At about 7:20am of 15 January 2008, a concerned citizen called a certain PO3 Esteves, police radio operator of the Nagcarlan Police Station, informing him that a certain alias “Baho” who was later identified as Veridiano, was on the way to San Pablo City to obtain illegal drugs. PO3 Esteves immediately relayed the information to PO1 Cabello and PO3 Alvin Vergara who were both on duty. Chief of Police June Urquia instructed PO1 Cabello and PO2 Vergara to set up a checkpoint at Barangay Taytay, Nagcarlan, Laguna. The police officers at the checkpoint personally knew Veridiano. They chanced upon Veridiano at around 10PM inside a passenger jeepney coming from San Pablo, Laguna. They flagged down the jeepney and asked the passengers to disembark. The police officers instructed the passengers to raise their t-shirts to check for possible concealed weapons and to remove the contents of their pockets. The police officers recovered from Veridiano “a tea bag containing what appeared to be marijuana.” PO1 Cabello confiscated the tea bag and marked it with his initials. Veridiano was arrested and apprised of his constitutional rights. He was then brought to the police station. At the police station, PO1 Cabello turned over the seized tea bag to PO1 Solano, who also placed his initials. PO1 Solano then made a laboratory examination request, which he personally brought with the seized tea bag to the Philippine National Police crime laboratory. The contents of the tea bag tested positive for marijuana. 2.) RTC found Veridiano guilty beyond reasonable doubt for the crime of illegal possession of marijuana. 3.) Veridiano appealed the decision of the trial court asserting that "he was illegally arrested." The CA rendered a Decision affirming the guilt of Veridiano. 4.) The Court of Appeals found that "Veridiano was caught in flagrante delicto" of having marijuana in his possession. 5.) Veridiano moved for reconsideration which was denied. 6.) Veridiano filed a Petition for Review on Certiorari. Petition was granted. Issue: Whether there was a valid warrantless search against petitioner Ruling: Petitioner's warrantless arrest was unlawful. A search incidental to a lawful arrest requires that there must first be a lawful arrest before a search is made. Otherwise stated, a lawful arrest must precede the search; "the process cannot be reversed." 78For there to be a lawful arrest, law enforcers must be armed with a valid warrant. Nevertheless, an arrest may also be effected without a warrant. There are three (3) grounds that will justify a warrantless arrest. Rule 113, Section 5 of the Revised Rules of Criminal Procedure provides:chanRoblesvirtualLawlibrary Section 5. Arrest Without Warrant; When Lawful. — A peace officer or a private person may, without a warrant, arrest a person:chanRoblesvirtualLawlibrary (a) When, in his presence, the person to be arrested has committed, is actually committing, or is attempting to commit an offense; (b) When an offense has just been committed and he has probable cause to believe based on personal knowledge of facts or circumstances that the person to be arrested has committed it; and (c) When the person to be arrested is a prisoner who has escaped from a penal establishment or place where he is serving final judgment or is temporarily confined while his case is pending, or has escaped while being transferred from one confinement to another. The first kind of warrantless arrest is known as an in flagrante delicto arrest. The validity of this warrantless arrest requires compliance with the overt act test79 as explained in Cogaed: [F]or a warrantless arrest of in flagrante delicto to be affected, "two elements must concur: (1) the person to be arrested must execute an overt act indicating that he [or she] has just committed, is actually committing, or is attempting to commit a crime; and (2) such overt act is done in the presence or within the view of the arresting officer.” Failure to comply with the overt act test renders an in flagrante delicto arrest constitutionally infirm. In Cogaed, the warrantless arrest was invalidated as an in flagrante delicto arrest because the accused did not exhibit an overt act within the view of the police officers suggesting that he was in possession of illegal drugs at the time he was apprehended. Rule 113, Section 5(b) of the Rules of Court pertains to a hot pursuit arrest. 92 The rule requires that an offense has just been committed. It connotes "immediacy in point of time." 93 That a crime was in fact committed does not automatically bring the case under this rule. 94 An arrest under Rule 113, Section 5(b) of the Rules of Court entails a time element from the moment the crime is committed up to the point of arrest. In this case, petitioner's arrest could not be justified as an in flagrante delicto arrest under Rule 113, Section 5(a) of the Rules of Court. He was not committing a crime at the checkpoint. Petitioner was merely a passenger who did not exhibit any unusual conduct in the presence of the law enforcers that would incite suspicion. In effecting the warrantless arrest, the police officers relied solely on the tip they received. Reliable information alone is insufficient to support a warrantless arrest absent any overt act from the person to be arrested indicating that a crime has just been committed, was being committed, or is about to be committed. The warrantless arrest cannot likewise be justified under Rule 113, Section 5(b) of the Revised Rules of Criminal Procedure. The law enforcers had no personal knowledge of any fact or circumstance indicating that petitioner had just committed an offense. A hearsay tip by itself does not justify a warrantless arrest. Law enforcers must have personal knowledge of facts, based on their observation, that the person sought to be arrested has just committed a crime. This is what gives rise to probable cause that would justify a warrantless search under Rule 113, Section 5(b) of the Revised Rules of Criminal Procedure. Moreover, petitioner's silence or lack of resistance can hardly be considered as consent to the warrantless search. Although the right against unreasonable searches and seizures may be surrendered through a valid waiver, the prosecution must prove that the waiver was executed with clear and convincing evidence.134 Consent to a warrantless search and seizure must be "unequivocal, specific, intelligently given . . . [and unattended] by duress or coercion." In the present case, the extensive search conducted by the police officers exceeded the allowable limits of warrantless searches. They had no probable cause to believe that the accused violated any law except for the tip they received. They did not observe any peculiar activity from the accused that may either arouse their suspicion or verify the tip. Moreover, the search was flawed at its inception. The checkpoint was set up to target the arrest of the accused. The warrantless search conducted by the police officers is invalid. Consequently, the tea bag containing marijuana seized from petitioner is rendered inadmissible under the exclusionary principle in Article III, Section 3(2) of the Constitution. There being no evidence to support his conviction, petitioner must be acquitted. WHEREFORE, the Decision dated July 16, 2010 of the Regional Trial Court in Criminal Case No. 16976-SP and the Decision dated November 18, 2011 and Resolution dated January 25, 2012 of the Court of Appeals in CA-GR. CR. No. 33588 are REVERSED and SET ASIDE. Petitioner Mario Veridiano y Sapi is hereby ACQUITTED and is ordered immediately RELEASED from confinement unless he is being held for some other lawful cause. PEOPLE OF THE PHILIPPINES, vs.JERIC PAVIA Y PALIZA @ "JERIC" Facts: On 29 March 2005, at around 6:00 in the evening, a confidential informant reported to SPO3 Melchor delaPeña (SPO3 Dela Peña) of the San Pedro Municipal Police Station, San Pedro, Laguna, that a pot session was taking place at the house of a certain "Obet" located at Barangay Cuyab, San Pedro, Laguna. Upon receipt of the information, SPO3 Dela Peña formed a team to conduct police operations against the suspect. The team was composed of the confidential informant, PO2 Rommel Bautista (PO2 Bautista), PO3 Jay Parunggao (PO3 Parunggao), PO1 Jifford Signap and SPO3 Dela Peña as team leader.3 At around 9:00 in the evening of the same date, the team proceeded to the target area. When the team arrived, the members saw that Obet’s house was closed. Since the house was not surrounded by a fence, PO2 Bautista approached the house and peeped through a small opening in a window where he saw four persons in a circle having a pot session in the living room. PO3 Parunggao then tried to find a way to enter the house and found an unlocked door. He entered the house,followed by PO2 Bautista and they caught the four persons engaged in a pot session by surprise. After they introduced themselves as police officers, they arrested the four suspects and seized the drug paraphernalia found at the scene.4 Among those arrested were herein appellants, from each of whom a plastic sachet containing white crystalline substance were confiscated by PO3 Parunggao after he conducted a body search on their persons.5 PO3 Parunggao marked the plastic sachet he seized from appellant Pavia with "JP," representing the initials of Jeric Pavia while that taken from appellant Buendia was marked, also by PO3 Parunggao, with "JB," representing the initials of Juan Buendia.6 These plastic sachets were transmitted tothe crime laboratory for qualitative examination where they tested positive for "shabu."7 Consequently, appellants were charged with violation of Section 13, Article II of R.A. No. 9165 in two separate but identically worded informations which read: That on or about 29 March 2005, in the Municipality of San Pedro, Province of Laguna, Philippines, and within the jurisdiction of this Honorable Court accused without authority of the law, did then and there willfully, unlawfully and feloniously have in his possession, control and custody [of] METHAMPHETAMINE HYDROCHLORIDE, commonly known as shabu, a dangerous drug, weighing zero point zero two (0.02) gram, in the company of two persons.8 When arraigned, both appellants pleaded not guilty to the offense.9 A joint trial of the cases ensued. In defense, appellants provided a different version of the incident. According to them, on the questioned date and time, they were roaming the streets of Baranggay Cuyab, selling star apples. A prospective buyer of the fruits called them over to his house and requested them to go inside, to which they acceded. Whenthey were about to leave the house, several persons who introduced themselves as policemen arrived and invited appellants to go with them to the precinct. There, they were incarcerated and falsely charged with violation of the Comprehensive Drugs Act of 2002.10 The Ruling of the RTC The trial court found that the prosecution was able to prove the offense charged through the spontaneous, positive and credible testimony of its witness. Thus, the testimony of PO2 Bautista on the witness stand, narrating the events leading to the apprehension of appellants, deserves full faith and credit.11 The Ruling of the Court of Appeals On appeal, the CA affirmed the decision of the RTC, upon a finding that the evidence on record support the trial court’s conclusion that a lawful arrest, search and seizure took place, and that the prosecution fully discharged its burden of establishing, beyond reasonable doubt, all the elements necessary for the conviction of the offense charged. On the contention of appellants that their warrantless arrest was illegal and, therefore, the items seized from them as a result of that arrest were inadmissible in evidence against them, the CA held that this argument totally lacks merit. Issue: WON warrantless arrest was illegal Held; Paragraph (a) of Section 5 is commonly known as an in flagrante delicto arrest. For a warrantless arrest of an accused caught in flagrante delictoto be valid, two requisites must concur: (1) the person to be arrested must execute an overt act indicating that he has just committed, is actually committing, or is attempting to commit a crime; and (2) such overt act is done in the presence or within the view of the arresting officer. After a careful evaluation of the evidence in its totality, we hold that the prosecution successfully established that the petitioner was arrested in flagrante delicto. We emphasize that the series of events that led the police to the house where the pot session was conducted and to their arrest were triggered by a "tip" from a concerned citizen that a "pot session" was in progress at the house of a certain "Obet" at Baranggay Cuyab, San Pedro, Laguna. Under the circumstances, the police did not have enough time to secure a search warrant considering the "time element" involved in the process (i.e., a pot session may not bean extended period of time and it was then 9:00 p.m.). In view of the urgency, SPO3 Melchor dela Peña immediately dispatched his men to proceed to the identified place to verify the report. At the place, the responding police officers verified through a small opening in the window and saw the accused-appellants and their other two (2) companions sniffing "shabu" to use the words of PO2 Bautista. There was therefore sufficient probable cause for the police officers to believe that the accused-appellants were then and there committing a crime. As it turned out, the accused-appellants indeed possessed and were even using a prohibited drug, contrary to law. When an accused is caught in flagrante delicto, the police officers are not only authorized but are duty-bound to arrest him even without a warrant. In the course of the arrest and in accordance with police procedures, the [appellants] were frisked, which search yielded the prohibited drug in their possession. These circumstances were sufficient to justify the warrantless search x x x thatyielded two (2) heat-sealed plastic sachets of "shabu Contrary to what the [appellants] want to portray, the chain of custody of the seized prohibited drug was shown not to have been broken. After the seizure of the plastic sachets containing white crystalline substance from the [appellants'] possession and of the various drug paraphernalia in the living room, the police immediately brought the [appellants] to the police station, together with the seized items. PO3 Parunggao himself brought these items to the police station and marked them. The plastic sachets containing white crystalline substance was marked "JB" and "JP". These confiscated items were immediately turned over by PO2 Bautista to the PNP Regional Crime Laboratory Office Calabarzon, Camp Vicente Lim, Calamba City for examination to determine the presence of dangerous drugs. After a qualitative examination conducted on the specimens, Forensic Chemist Lorna Ravelas Tria concluded that the plastic sachets recovered from the accused-appellants tested positive for methylamphetamine hydrochloride, a prohibited drug, per Chemistry Report Nos. D-0381-05 and D-0382-05. When the prosecution presented these marked specimens in court, PO2 Baustista positively identified them to be the same items they seized from the [appellants] and which PO3 Parunggao later marked at the police station, from where the seized items were turned over to the laboratory for examination based on a duly prepared request. Thus, the prosecution established the crucial link in the chain of custody of the seized items from the time they were first discovered until they were brought for examination. Besides, as earlier stated, the [appellants] did not contest the admissibility of the seized items during the tria1. The integrity and the evidentiary value of the drugs seized from the accused-appellants were therefore duly proven not to have been compromised. PESTILOS VS GENEROSO FACTS: The petitioners were indicted for attempted murder. Petitioners filed an Urgent Motion for Regular Preliminary Investigation on the ground that there no valid warrantless arrest took place. The RTC denied the motion and the CA affirmed the denial. Records show that an altercation ensued between the petitioners and Atty. Moreno Generoso. The latter called the Central Police District to report the incident and acting on this report, SPO1 Monsalve dispatched SPO2 Javier to go to the scene of the crime and render assistance. SPO2, together with augmentation personnel arrived at the scene of the crime less than one hour after the alleged altercation and saw Atty. Generoso badly beaten. Atty. Generoso then pointed the petitioners as those who mauled him which prompted the police officers to “invite” the petitioners to go to the police station for investigation. At the inquest proceeding, the City Prosecutor found that the petitioners stabbed Atty. Generoso with a bladed weapon who fortunately survived the attack. Petitioners aver that they were not validly arrested without a warrant. ISSUE: Are the petitioners validly arrested without a warrant when the police officers did not witness the crime and arrived only less than an hour after the alleged altercation? HELD: YES, the petitioners were validly arrested without a warrant. Section 5(b), Rule 113 of the Revised Rules of Criminal Procedure provides that: When an offense has just been committed, and he has probable cause to believe based on personal knowledge of facts or circumstances that the person to be arrested has committed it. The elements under Section 5(b), Rule 113 of the Revised Rules of Criminal Procedure are: first, an offense has just been committed; and second, the arresting officer has probable cause to believe based on personal knowledge of facts or circumstances that the person to be arrested has committed it. The Court’s appreciation of the elements that “the offense has just been committed” and ”personal knowledge of facts and circumstances that the person to be arrested committed it” depended on the particular circumstances of the case. The element of ”personal knowledge of facts or circumstances”, however, under Section 5(b), Rule 113 of the Revised Rules of Criminal Procedure requires clarification. Circumstances may pertain to events or actions within the actual perception, personal evaluation or observation of the police officer at the scene of the crime. Thus, even though the police officer has not seen someone actually fleeing, he could still make a warrantless arrest if, based on his personal evaluation of the circumstances at the scene of the crime, he could determine the existence of probable cause that the person sought to be arrested has committed the crime. However, the determination of probable cause and the gathering of facts or circumstances should be made immediately after the commission of the crime in order to comply with the element of immediacy. In other words, the clincher in the element of ”personal knowledge of facts or circumstances” is the required element of immediacy within which these facts or circumstances should be gathered. With the facts and circumstances of the case at bar that the police officers gathered and which they have personally observed less than one hour from the time that they have arrived at the scene of the crime, it is reasonable to conclude that the police officers had personal knowledge of the facts and circumstances justifying the petitioners’ warrantless arrests. Hence, the petitioners were validly arrested and the subsequent inquest proceeding was likewise appropriate. PEOPLE VS VILLAREAL MARCH 2013 On December 25, 2006 at around 11:30 in the morning, as PO3 Renato de Leon (PO3 de Leon) was driving his motorcycle on his way home along 5th Avenue, he saw appellant from a distance of about 8 to 10 meters, holding and scrutinizing in his hand a plastic sachet of shabu. Thus, PO3 de Leon, a member of the Station Anti-Illegal Drugs-Special Operation Unit (SAIDSOU) in Caloocan City, alighted from his motorcycle and approached the appellant whom he recognized as someone he had previously arrested for illegal drug possession.4 Upon seeing PO3 de Leon, appellant tried to escape but was quickly apprehended with the help of a tricycle driver. Despite appellant’s attempts to resist arrest, PO3 de Leon was able to board appellant onto his motorcycle and confiscate the plastic sachet of shabu in his possession. Thereafter, PO3 de Leon brought appellant to the 9th Avenue Police Station to fix his handcuffs, and then they proceeded to the SAID-SOU office where PO3 de Leon marked the seized plastic sachet with "RZL/NV 12-25-06," representing his and appellant’s initials and the date of the arrest.5 Subsequently, PO3 de Leon turned over the marked evidence as well as the person of appellant to the investigator, PO2 Randulfo Hipolito (PO2 Hipolito) who, in turn, executed an acknowledgment receipt6 and prepared a letter request7 for the laboratory examination of the seized substance. PO2 Hipolito personally delivered the request and the confiscated item to the Philippine National Police (PNP) Crime Laboratory, which were received by Police Senior Inspector Albert Arturo (PSI Arturo), the forensic chemist.8 Upon qualitative examination, the plastic sachet, which contained 0.03 gram of white crystalline substance, tested positive for methylamphetamine hydrochloride, a dangerous drug. 9 Consequently, appellant was charged with violation of Section 11, Article II of RA 9165 for illegal possession of dangerous drugs in an Information10 which reads: That on or about the 25th day of December, 2006 in Caloocan City, Metro Manila and within the jurisdiction of this Honorable Court, the above-named accused, without being authorized by law, did then and there willfully, unlawfully and feloniously have in his possession, custody and control, METHYLAMPHETAMINE HYDROCHLORIDE (Shabu) weighing 0.03 gram which, when subjected to chemistry examination gave positive result of METHYLAMPHETAMIME HYDROCHLORIDE, a dangerous drug. CONTRARY TO LAW. When arraigned, appellant, assisted by counsel de oficio, entered a plea of not guilty to the offense charged.11 In his defense, appellant denied PO3 de Leon’s allegations and instead claimed that on the date and time of the incident, he was walking alone along Avenida, Rizal headed towards 5th Avenue when someone who was riding a motorcycle called him from behind. Appellant approached the person, who turned out to be PO3 de Leon, who then told him not to run, frisked him, and took his wallet which contained ₱1,000.00.12 Appellant was brought to the 9th Avenue police station where he was detained and mauled by eight other detainees under the orders of PO3 de Leon. Subsequently, he was brought to the Sangandaan Headquarters where two other police officers, whose names he recalled were "Michelle" and "Hipolito," took him to the headquarters’ firing range. There, "Michelle" and "Hipolito" forced him to answer questions about a stolen cellphone, firing a gun right beside his ear each time he failed to answer and eventually mauling him when he continued to deny knowledge about the cellphone.13 Thus, appellant sustained head injuries for which he was brought to the Diosdado Macapagal Hospital for proper treatment.14 The following day, he underwent inquest proceedings before one Fiscal Guiyab, who informed him that he was being charged with resisting arrest and "Section 11."15 The first charge was eventually dismissed. The RTC Ruling After trial on the merits, the RTC convicted appellant as charged upon a finding that all the elements of the crime of illegal possession of dangerous drugs have been established, In its assailed Decision, the CA sustained appellant’s conviction, finding "a clear case of in flagrante delicto warrantless arrest"17 as provided under Section 5, Rule 113 of the Revised Rules of Criminal Procedure. The CA held that appellant "exhibited an overt act or strange conduct that would reasonably arouse suspicion,"18 aggravated by the existence of his past criminal citations and his attempt to flee when PO3 de Leon approached him. ISSUE HELD The appeal is meritorious. Section 5, Rule 113 of the Revised Rules of Criminal Procedure lays down the basic rules on lawful warrantless arrests, either by a peace officer or a private person, as follows: Sec. 5. Arrest without warrant; when lawful. – A peace officer or a private person may, without a warrant, arrest a person: (a) When, in his presence, the person to be arrested has committed, is actually committing, or is attempting to commit an offense; (b) When an offense has just been committed and he has probable cause to believe based on personal knowledge of facts or circumstances that the person to be arrested has committed it; and (c) When the person to be arrested is a prisoner who has escaped from a penal establishment or place where he is serving final judgment or is temporarily confined while his case is pending, or has escaped while being transferred from one confinement to another. xxx For the warrantless arrest under paragraph (a) of Section 5 to operate, two elements must concur: (1) the person to be arrested must execute an overt act indicating that he has just committed, is actually committing, or is attempting to commit a crime; and (2) such overt act is done in the presence or within the view of the arresting officer.19 On the other hand, paragraph (b) of Section 5 requires for its application that at the time of the arrest, an offense had in fact just been committed and the arresting officer had personal knowledge of facts indicating that the appellant had committed it.20 In both instances, the officer’s personal knowledge of the fact of the commission of an offense is absolutely required. Under paragraph (a), the officer himself witnesses the crime while under paragraph (b), he knows for a fact that a crime has just been committed. In sustaining appellant’s conviction in this case, the appellate court ratiocinated that this was a clear case of an "in flagrante delicto warrantless arrest" under paragraphs (a) and (b) of Section 5, Rule 113 of the Revised Rules on Criminal Procedure, as above-quoted. However, a previous arrest or existing criminal record, even for the same offense, will not suffice to satisfy the exacting requirements provided under Section 5, Rule 113 in order to justify a lawful warrantless arrest. "Personal knowledge" of the arresting officer that a crime had in fact just been committed is required. To interpret "personal knowledge" as referring to a person’s reputation or past criminal citations would create a dangerous precedent and unnecessarily stretch the authority and power of police officers to effect warrantless arrests based solely on knowledge of a person’s previous criminal infractions, rendering nugatory the rigorous requisites laid out under Section 5. It was therefore error on the part of the CA to rule on the validity of appellant’s arrest based on "personal knowledge of facts regarding appellant’s person and past criminal record," as this is unquestionably not what "personal knowledge" under the law contemplates, which must be strictly construed. People v. Martinez et al. G.R. No. 191366, December 13, 2010 FACTS: On September 2, 2006 at around 1245 PM, PO1 Bernard Azarden was on duty at the Police Community Precinct along Arellano St., Dagupan City when a concerned citizen reported that a pot session was underway in the house of accused Rafael Gonzales in Trinidad Subdivision, Dagupan City. PO1 Azardan, PO1 Alejandro dela Cruz and members of Special Weapons and Tactics (SWAT) proceeded to aforesaid house. Upon inquiry from people in the area, the house of Gonzales was located. As the team entered the house, accused Orlando Doria was arrested while coming out. Inside the house were Gonzales, Arnold Martinez, Edgar Dizon, and Rezin Martinez. Seized from the accused were open plastic sachets (containing shabu residue), pieces of rolled used aluminum foil and pieces of used aluminum foil. The accused were arrested and brought to police station, seized items were sent to the Pangasinan Provincial Police Crime Laboratory. All accused, except for Doria, were found positive for methylamphetamine HCL. On February 13, 2008, RTC found Arnold Martinez, Edgar Dizon, Rezin Martinez and Rafael Gonzales guilty beyond reasonable doubt under Sec. 13 in relation to Sec. 11, Art. II of RA 9165 and sentenced each to life imprisonment and fined PHP 500,000 plus cost of suit. The CA supported the findings of the lower court. ISSUE: Were the guilt of the accused proven beyond reasonable doubt? RULING: No, the Court finds that the prosecution failed to prove the guilt of the accused beyond reasonable doubt because (1) evidence against the accused are inadmissible and (2) even if the evidence were admissible, the chain of custody was not duly established . The evidence is inadmissible because of the illegal arrest, search and seizure. Searches and seizures without a warrant are valid in (1) incidence of lawful arrest, (2) “plain view” search of evidence, (3) moving vehicle search, (4) consented search, (5) customs search, (6) stop and frisk, (7)exigent and emergency cases. Under Rule 113, Sec. 5 of RRCP warrantless arrest can only be done in in flagrante cases, hot pursuit cases, and fugitive cases. The arrest of the accusedappellants were based solely on the report of a concerned citizen, no surveillance of the place was conducted. Under Rule 113, fugitive case does not apply. In flagrante and hot pursuit case may apply only upon probable cause, which means actual belief or reasonable ground of suspicion. It is reasonable ground of suspicion when suspicion of a person to be arrested is probably guilty of the offense based on actual facts, that is, supported by circumstances. In case at bar, this is not the case since the entire arrest was based on uncorroborated statement of a concerned citizen. The chain of custody as outlined in Sec. 21, Art. II of RA 9165 was not observed as no proper inventory, photographing, was done in the presence of the accused nor were there representatives from the media, the DOJ and any popularly elected official present, although in warrantless seizures, marking and photographing of evidence may be done at the nearest police station. Court sets aside and reverses the decision of the CA dated August 7, 2009, acquits the accused and orders their immediate release.