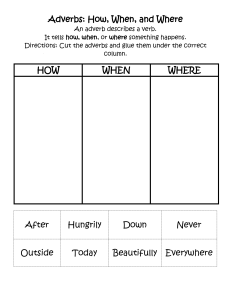

https://www.grammarly.com/blog/adverb/#:~:text=An%20adverb%20is%20a%20word,same %20as%20their%20adjective%20counterparts. What is an adverb? An adverb is a word that modifies (describes) a verb (he sings loudly), an adjective (very tall), another adverb (ended too quickly), or even a whole sentence (Fortunately, I had brought an umbrella). Adverbs often end in -ly, but some (such as fast) look exactly the same as their adjective counterparts. Tom Longboat did not run badly. Tom is very tall. The race finished too quickly. Fortunately, Lucy recorded Tom’s win. It’s easy to identify adverbs in these sentences. Adverbs and verbs Adverbs often modify verbs. This means that they describe the way an action is happening. Phillip sings loudly in the shower. My cat waits impatiently for his food. I will seriously consider your suggestion. The adverbs in each of the sentences above answer the question in what manner? How does Phillip sing? Loudly. How does my cat wait? Impatiently. How will I consider your suggestion? Seriously. Adverbs can answer other types of questions about how an action was performed. They can also tell you when (We arrived early) and where (Turn here). However, there is one type of verb that doesn’t mix well with adverbs. Linking verbs, such as feel, smell, sound, seem, and appear, typically need adjectives, not adverbs. A very common example of this type of mixup is I feel badly about what happened. Because “feel” is a verb, it seems to call for an adverb rather than an adjective. But “feel” isn’t just any verb; it’s a linking verb. An adverb would describe how you perform the action of feeling—an adjective describes what you feel. “I feel badly” means that you are bad at feeling things. If you’re trying to read Braille through thick leather gloves, then it might make sense for you to say “I feel badly.” But if you’re trying to say that you are experiencing negative emotions, “I feel bad” is the phrase you want. Adverbs and adjectives Adverbs can also modify adjectives and other adverbs. Often, the purpose of the adverb is to add a degree of intensity to the adjective. The woman is quite pretty. This book is more interesting than the last one. The weather report is almost always right. The adverb almost is modifying the adverb always, and they’re both modifying right. “Is my singing too loud?” asked Phillip. My cat is incredibly happy to have his dinner. We will be slightly late to the meeting. This bridesmaid dress is a very unflattering shade of puce. Adverbs and other adverbs You can use an adverb to describe another adverb. In fact, if you wanted to, you could use several. Phillip sings rather enormously too loudly. The problem is that it often produces weak and clunky sentences like the one above, so be careful not to overdo it. Adverbs and sentences Some adverbs can modify entire sentences—unsurprisingly, these are called sentence adverbs. Common ones include generally, fortunately, interestingly, and accordingly. Sentence adverbs don’t describe one particular thing in the sentence—instead, they describe a general feeling about all of the information in the sentence. Fortunately, we got there in time. Interestingly, no one at the auction seemed interested in bidding on the antique spoon collection. At one time, the use of the word hopefully as a sentence adverb (e.g., Hopefully, I’ll get this job) was condemned. People continued to use it though, and many style guides and dictionaries now accept it. There are still plenty of readers out there who hate it though, so it’s a good idea to avoid using it in formal writing. Degrees of comparison Like adjectives, adverbs can show degrees of comparison, although it’s slightly less common to use them this way. With certain “flat adverbs” (adverbs that look exactly the same as their adjective counterparts), the comparative and superlative forms look the same as the adjective comparative and superlative forms. It’s usually better to use stronger adverbs (or stronger adjectives and verbs) rather than relying on comparative and superlative adverbs. An absolute adverb describes something in its own right: He smiled warmly A hastily written note To make the comparative form of an adverb that ends in -ly, add the word more: He smiled more warmly than the others. The more hastily written note contained the clue. To make the superlative form of an adverb that ends in -ly, add the word most: He smiled most warmly of them all. The most hastily written note on the desk was overlooked. Placement of adverbs Place adverbs as close as possible to the words they are supposed to modify. Putting the adverb in the wrong spot can produce an awkward sentence at best and completely change the meaning at worst. Be especially careful about the word only, which is one of the most often misplaced modifiers. Consider the difference between these two sentences: Phillip only fed the cat. Phillip fed only the cat. The first sentence means that all Phillip did was feed the cat. He didn’t pet the cat or pick it up or anything else. The second sentence means that Phillip fed the cat, but he didn’t feed the dog, the bird, or anyone else who might have been around. When an adverb is modifying a verb phrase, the most natural place for the adverb is usually the middle of the phrase. We are quickly approaching the deadline. Phillip has always loved singing. I will happily assist you. When to avoid adverbs Ernest Hemingway is often held up as an example of a great writer who detested adverbs and advised other writers to avoid them. In reality, it’s impossible to avoid adverbs altogether. Sometimes we need them, and all writers (even Hemingway) use them occasionally. The trick is to avoid unnecessary adverbs. When your verb or adjective doesn’t seem powerful or precise enough, instead of reaching for an adverb to add more color, try reaching for a stronger verb or adjective instead. Most of the time, you’ll come up with a better word and your writing will be stronger for it. Definition Adverbs are words that modify a verb (He drove slowly. — How did he drive?) an adjective (He drove a very fast car. — How fast was his car?) another adverb (She moved quite slowly down the aisle. — How slowly did she move?) As we will see, adverbs often tell when, where, why, or under what conditions something happens or happened. Adverbs frequently end in -ly; however, many words and phrases not ending in -ly serve an adverbial function and an -ly ending is not a guarantee that a word is an adverb. The words lovely, lonely, motherly, friendly, neighborly, for instance, are adjectives: That lovely woman lives in a friendly neighborhood. If a group of words containing a subject and verb acts as an adverb (modifying the verb of a sentence), it is called an Adverb Clause: When this class is over, we're going to the movies. When a group of words not containing a subject and verb acts as an adverb, it is called an adverbial phrase. Prepositional phrases frequently have adverbial functions (telling place and time, modifying the verb): He went to the movies. She works on holidays. They lived in Canada during the war. And Infinitive phrases can act as adverbs (usually telling why): She hurried to the mainland to see her brother. The senator ran to catch the bus. But there are other kinds of adverbial phrases: He calls his mother as often as possible. Adverbs can modify adjectives, but an adjective cannot modify an adverb. Thus we would say that "the students showed a really wonderful attitude" and that "the students showed a wonderfully casual attitude" and that "my professor is really tall, but not "He ran real fast." Like adjectives, adverbs can have comparative and superlative forms to show degree. Walk faster if you want to keep up with me. The student who reads fastest will finish first. We often use more and most, less and least to show degree with adverbs: With sneakers on, she could move more quickly among the patients. The flowers were the most beautifully arranged creations I've ever seen. She worked less confidently after her accident. That was the least skillfully done performance I've seen in years. The as — as construction can be used to create adverbs that express sameness or equality: "He can't run as fast as his sister." A handful of adverbs have two forms, one that ends in -ly and one that doesn't. In certain cases, the two forms have different meanings: He arrived late. Lately, he couldn't seem to be on time for anything. In most cases, however, the form without the -ly ending should be reserved for casual situations: She certainly drives slow in that old Buick of hers. He did wrong by her. He spoke sharp, quick, and to the point. Adverbs often function as intensifiers, conveying a greater or lesser emphasis to something. Intensifiers are said to have three different functions: they can emphasize, amplify, or downtone. Here are some examples: Emphasizers: o I really don't believe him. o He literally wrecked his mother's car. o She simply ignored me. o They're going to be late, for sure. Amplifiers: o The teacher completely rejected her proposal. o I absolutely refuse to attend any more faculty meetings. o They heartily endorsed the new restaurant. o I so wanted to go with them. o We know this city well. Downtoners: o I kind of like this college. o Joe sort of felt betrayed by his sister. o His mother mildly disapproved his actions. o We can improve on this to some extent. o The boss almost quit after that. o The school was all but ruined by the storm. Adverbs (as well as adjectives) in their various degrees can be accompanied by premodifiers: She runs very fast. We're going to run out of material all the faster This issue is addressed in the section on degrees in adjectives. For this section on intensifiers, we are indebted to A Grammar of Contemporary English by Randolph Quirk, Sidney Greenbaum, Geoffrey Leech, and Jan Svartvik. Longman Group: London. 1978. pages 438 to 457. Examples our own. Using Adverbs in a Numbered List Within the normal flow of text, it's nearly always a bad idea to number items beyond three or four, at the most. Anything beyond that, you're better off with a vertical list that uses numbers (1, 2, 3, etc.). Also, in such a list, don't use adverbs (with an -ly ending); use instead the uninflected ordinal number (first, second, third, fourth, fifth, etc.). First (not firstly), it's unclear what the adverb is modifying. Second (not secondly), it's unnecessary. Third (not thirdly), after you get beyond "secondly," it starts to sound silly. Adverbs that number in this manner are treated as disjuncts (see below.) Adverbs We Can Do Without Review the section on Being Concise for some advice on adverbs that we can eliminate to the benefit of our prose: intensifiers such as very, extremely, and really that don't intensify anything and expletive constructions ("There are several books that address this issue.") Kinds of Adverbs Adverbs of Manner She moved slowly and spoke quietly. Adverbs of Place She has lived on the island all her life. She still lives there now. Adverbs of Frequency She takes the boat to the mainland every day. She often goes by herself. Adverbs of Time She tries to get back before dark. It's starting to get dark now. She finished her tea first. She left early. Adverbs of Purpose She drives her boat slowly to avoid hitting the rocks. She shops in several stores to get the best buys. Positions of Adverbs One of the hallmarks of adverbs is their ability to move around in a sentence. Adverbs of manner are particularly flexible in this regard. Solemnly the minister addressed her congregation. The minister solemnly addressed her congregation. The minister addressed her congregation solemnly. The following adverbs of frequency appear in various points in these sentences: Before the main verb: I never get up before nine o'clock. Between the auxiliary verb and the main verb: I have rarely written to my brother without a good reason. Before the verb used to: I always used to see him at his summer home. Indefinite adverbs of time can appear either before the verb or between the auxiliary and the main verb: He finally showed up for batting practice. She has recently retired. Order of Adverbs There is a basic order in which adverbs will appear when there is more than one. It is similar to The Royal Order of Adjectives, but it is even more flexible. THE ROYAL ORDER OF ADVERBS Verb Beth swims Manner Place Frequency Time Purpose in the pool every morning before dawn to keep in shape. Dad walks impatiently into town every afternoon before supper to get a newspaper. Tashonda naps in her room every morning before lunch. enthusiastically In actual practice, of course, it would be highly unusual to have a string of adverbial modifiers beyond two or three (at the most). Because the placement of adverbs is so flexible, one or two of the modifiers would probably move to the beginning of the sentence: "Every afternoon before supper, Dad impatiently walks into town to get a newspaper." When that happens, the introductory adverbial modifiers are usually set off with a comma. More Notes on Adverb Order As a general principle, shorter adverbial phrases precede longer adverbial phrases, regardless of content. In the following sentence, an adverb of time precedes an adverb of frequency because it is shorter (and simpler): Dad takes a brisk walk before breakfast every day of his life. A second principle: among similar adverbial phrases of kind (manner, place, frequency, etc.), the more specific adverbial phrase comes first: My grandmother was born in a sod house on the plains of northern Nebraska. She promised to meet him for lunch next Tuesday. Bringing an adverbial modifier to the beginning of the sentence can place special emphasis on that modifier. This is particularly useful with adverbs of manner: Slowly, ever so carefully, Jesse filled the coffee cup up to the brim, even above the brim. Occasionally, but only occasionally, one of these lemons will get by the inspectors. Inappropriate Adverb Order Review the section on Misplaced Modifiers for some additional ideas on placement. Modifiers can sometimes attach themselves to and thus modify words that they ought not to modify. They reported that Giuseppe Balle, a European rock star, had died on the six o'clock news. Clearly, it would be better to move the underlined modifier to a position immediately after "they reported" or even to the beginning of the sentence — so the poor man doesn't die on television. Misplacement can also occur with very simple modifiers, such as only and barely: She only grew to be four feet tall. It would be better if "She grew to be only four feet tall." Adjuncts, Disjuncts, and Conjuncts Regardless of its position, an adverb is often neatly integrated into the flow of a sentence. When this is true, as it almost always is, the adverb is called an adjunct. (Notice the underlined adjuncts or adjunctive adverbs in the first two sentences of this paragraph.) When the adverb does not fit into the flow of the clause, it is called a disjunct or a conjunct and is often set off by a comma or set of commas. A disjunct frequently acts as a kind of evaluation of the rest of the sentence. Although it usually modifies the verb, we could say that it modifies the entire clause, too. Notice how "too" is a disjunct in the sentence immediately before this one; that same word can also serve as an adjunct adverbial modifier: It's too hot to play outside. Here are two more disjunctive adverbs: Frankly, Martha, I don't give a hoot. Fortunately, no one was hurt. Conjuncts, on the other hand, serve a connector function within the flow of the text, signaling a transition between ideas. If they start smoking those awful cigars, then I'm not staying. We've told the landlord about this ceiling again and again, and yet he's done nothing to fix it. At the extreme edge of this category, we have the purely conjunctive device known as the conjunctive adverb (often called the adverbial conjunction): Jose has spent years preparing for this event; nevertheless, he's the most nervous person here. I love this school; however, I don't think I can afford the tuition. Authority for this section: A University Grammar of English by Randolph Quirk and Sidney Greenbaum. Longman Group: Essex, England. 1993. 126. Used with permission. Examples our own. Some Special Cases The adverbs enough and not enough usually take a postmodifier position: Is that music loud enough? These shoes are not big enough. In a roomful of elderly people, you must remember to speak loudly enough. (Notice, though, that when enough functions as an adjective, it can come before the noun: Did she give us enough time? The adverb enough is often followed by an infinitive: She didn't run fast enough to win. The adverb too comes before adjectives and other adverbs: She ran too fast. She works too quickly. If too comes after the adverb it is probably a disjunct (meaning also) and is usually set off with a comma: Yasmin works hard. She works quickly, too. The adverb too is often followed by an infinitive: She runs too slowly to enter this race. Another common construction with the adverb too is too followed by a prepositional phrase — for + the object of the preposition — followed by an infinitive: This milk is too hot for a baby to drink. Relative Adverbs Adjectival clauses are sometimes introduced by what are called the relative adverbs: where, when, and why. Although the entire clause is adjectival and will modify a noun, the relative word itself fulfills an adverbial function (modifying a verb within its own clause). The relative adverb where will begin a clause that modifies a noun of place: My entire family now worships in the church where my great grandfather used to be minister. The relative pronoun "where" modifies the verb "used to be" (which makes it adverbial), but the entire clause ("where my great grandfather used to be minister") modifies the word "church." A when clause will modify nouns of time: My favorite month is always February, when we celebrate Valentine's Day and Presidents' Day. And a why clause will modify the noun reason: Do you know the reason why Isabel isn't in class today? We sometimes leave out the relative adverb in such clauses, and many writers prefer "that" to "why" in a clause referring to "reason": Do you know the reason why Isabel isn't in class today? I always look forward to the day when we begin our summer vacation. I know the reason that men like motorcycles. Authority for this section: Understanding English Grammar by Martha Kolln. 4rth Edition. MacMillan Publishing Company: New York. 1994. Viewpoint, Focus, and Negative Adverbs A viewpoint adverb generally comes after a noun and is related to an adjective that precedes that noun: A successful athletic team is often a good team scholastically. Investing all our money in snowmobiles was probably not a sound idea financially. You will sometimes hear a phrase like "scholastically speaking" or "financially speaking" in these circumstances, but the word "speaking" is seldom necessary. A focus adverb indicates that what is being communicated is limited to the part that is focused; a focus adverb will tend either to limit the sense of the sentence ("He got an A just for attending the class.") or to act as an additive ("He got an A in addition to being published." Although negative constructions like the words "not" and "never" are usually found embedded within a verb string — "He has never been much help to his mother." — they are technically not part of the verb; they are, indeed, adverbs. However, a so-called negative adverb creates a negative meaning in a sentence without the use of the usual no/not/neither/nor/never constructions: He seldom visits. She hardly eats anything since the accident. After her long and tedious lectures, rarely was anyone awake. What is an adverb? An adverb is a word that can modify a verb, an adjective, or another adverb. Lots of adverbs end "-ly." For example: She swims quickly. (Here, the adverb "quickly" modifies the verb "swims.") She is an extremely quick swimmer. (The adverb "extremely" modifies the adjective "quick.") She swims extremely quickly. (The adverb "extremely" modifies the adverb "quickly.") What do adverbs do? When an adverb modifies a verb, it tells us how, when, where, why, how often, or how much the action is performed. Here are some examples of adverbs modifying verbs: How: He ran quickly. When: He ran yesterday. Where: He ran here. How often: He ran daily. How much: He ran fastest. Not all adverbs are one word. In the examples above, every adverb is a single word, but an adverb can be made up of more than one word. For example: How: He ran at 10 miles per hour. (The bold text is an adverbial phrase.) When: He ran when the police arrived. (The bold text is an adverbial clause.) Where: He ran to the shops. (adverbial phrase) Why: He ran to fetch some water. (This is an adverbial phrase. Look at the list above. There are no single-word adverbs that tell us why.) How often: He ran every day. (adverbial phrase) How much: He ran quicker than me. (adverbial phrase) Adverbs When beginners first learn about adverbs, they are often told that adverbs end "-ly" and modify verbs. That is, of course, true, but adverbs do far more than that description suggests. Here are three key points about adverbs: (Point 1) Adverbs modify verbs, but they can also modify adjectives and other adverbs. For example: She sang an insanely sad song extremely well. (In this example, "insanely" modifies the adjective "sad," "extremely" modifies the adverb "well," and "well" modifies the verb "sang.") (Point 2) Although many adverbs end "-ly," lots do not. For example: fast, never, well, very, most, least, more, less, now, far, there Adverbs Modifying Verbs An adverb that modifies a verb usually tells you how, when, where, why, how often, or how much the action is performed. (NB: The ones that end "ly" are usually the ones that tell us how the action is performed, e.g., "quickly," "slowly," "carefully," "quietly.") Here are some examples of adverbs modifying verbs: Anita placed the vase carefully on the shelf. (The word "carefully" is an adverb. It shows how the vase was placed.) Tara walks gracefully. (The word "gracefully" is an adverb. It modifies the verb "to walk.") He runs fast. (The word "fast" is an adverb. It modifies the verb "to run.") You can set your watch by him. He always leaves at 5 o'clock. (The word "always" is an adverb. It modifies the verb "to leave.") The dinner guests arrived early. (Here, "early" modifies "to arrive.") She sometimes helps us. (Here, "sometimes" modifies "to help.") Will you come quietly, or do I have to use earplugs? (Comedian Spike Milligan) (Here, "quietly" modifies "to come.") I am the only person in the world I should like to know thoroughly. (Playwright Oscar Wilde) (Here, "thoroughly" modifies "to know.") Adverbs Modifying Adjectives If you examine the word "adverb," you could be forgiven for thinking adverbs only modify verbs (i.e., "add" to "verbs"), but adverbs can also modify adjectives and other adverbs. Here are some examples of adverbs modifying adjectives: The horridly grotesque gargoyle was undamaged by the debris. (The adverb "horridly" modifies the adjective "grotesque.") Peter had an extremely ashen face. (The adverb "extremely" modifies the adjective "ashen.") Badly trained dogs that fail the test will become pets. (The adverb "badly" modifies the adjective "trained.") (Note: The adjective "trained" is an adjective formed from the verb "to train." It is called a participle.) She wore a beautifully designed dress. (The adverb "beautifully" modifies the adjective "designed.") Adverbs Modifying Adverbs Here are some examples of adverbs modifying adverbs: Peter Jackson finished his assignment remarkably quickly. (Here, the adverb "quickly" modifies the verb "to finish." The adverb "remarkably" modifies the adverb "quickly.") We're showing kids a world that is very scantily populated with women and female characters. They should see female characters taking up half the planet, which we do. (Actress Geena Davis) (In this example, the adverb "scantily" modifies the adjective "populated." The adverb "very" modifies the adverb "scantily.") More about Adverbs Types of Adverb When an adverb modifies a verb, it can often be categorized as one of the following: Type Examples Adverb of Manner (how) An adverb of manner tells us how an action occurs. Adverb of Time (when and how often) An adverb of time tells us when an action occurs or how often. The lion crawled stealthily. Will you come quietly, or do I have to use earplugs? (Comedian Spike Milligan) (NB: Lots of adverbs of manner end "-ly.") I tell him daily. What you plant now, you will harvest later. (Author Og Mandino) (NB: Adverbs of time that tell us how often something occurs (e.g., "always," "often," "sometimes") are also known as "adverbs of frequency.") Adverb of Place (where) An adverb of place tells us where an action occurs. Adverb of Degree (aka Adverb of Comparison) (how much) I did not put it there. Poetry surrounds us everywhere, but putting it on paper is, alas, not so easy as looking at it. (Artist Vincent Van Gogh) An adverb of degree tells us to what degree an action occurs. He works smarter. Doubters make me work harder to prove them wrong. (Businessman Derek Jeter) These are the main four categories. We'll discuss the others shortly. Don't forget that adverbs can also modify adjectives and other adverbs. To expect the unexpected shows a thoroughly modern intellect. (Playwright Oscar Wilde) (The adverb "thoroughly" modifies the adjective "modern.") If a thing is worth doing, it is worth doing very slowly. (Burlesque entertainer Gypsy Rose Lee) (The adverb "very" modifies the adverb "slowly.") Even More about Adverbs Adverbial Phrases and Clauses In all the examples above, the adverbs have been single words, but multi-word adverbs are common too. Adverbs commonly come as phrases (i.e., two or more words) or clauses (i.e., two or more words containing a subject and a verb). Below are some examples of multi-word adverbs. This list also includes adverbs of condition, adverbs of concession, and adverbs of reason. Type Examples Adverb of Manner An adverb of manner often starts with a preposition (e.g., "in," "with") or one of the following: "as," "like," or "the way." (These are called subordinating conjunctions.) Money speaks, but it speaks with a male voice. (Author Andrea Dworkin) (This is called a prepositional phrase. It's also an adverbial phrase.) Adverb of Time An adverb of time often starts with a preposition or one of the following subordinating conjunctions: "after," "as," "as long as," "as soon as," "before," "no sooner than," "since," "until," "when," or "while." Adverb of Place A company like Gucci can lose millions in a second. (Gucci CEO Marco Bizzarri) After the game has finished, the king and pawn go into the same box. (Italian proverb) An adverb of place often starts with a preposition or one of the following subordinating conjunctions: "anywhere," "everywhere," "where," or "wherever." Adverb of Degree (aka Adverb of Comparison) People who say they sleep like a baby does usually don't have one. (Psychologist Leo J. Burke) Opera is when a guy gets stabbed in the back and, instead of bleeding, he sings. (Ed Gardner) Some cause happiness wherever they go; others whenever they go. (Playwright Oscar Wilde) An adverb of degree often starts with one of the following subordinating conjunctions: "than," "as...as," "so...as," or "the...the." Nothing is so contagious as enthusiasm. (Poet Samuel Taylor Coleridge) Be what you are. This is the first step toward becoming better than you are. (Writer Julius Charles Hare) Read more about comparatives of adverbs (like "more cleverly"). Adverbs of Condition An adverb of condition tells us the condition needed before the main idea comes into effect. An adverb of condition often starts with "if" or "unless." If the facts don't fit the theory, change the facts. (Theoretical physicist Albert Einstein) Age doesn't matter, unless you're a cheese. (Filmmaker Luis Bunuel) Adverbs of Concession An adverb of concession contrasts with the main idea. An adverb of concession often starts with a subordinating conjunction like "though," "although," "even though," "while," "whereas," or "even if." Although golf was originally restricted to wealthy, overweight Protestants, today it's open to anybody who owns hideous clothing. (Comedian Dave Barry) A loud voice cannot compete with a clear voice, even if it's a whisper. (Writer Barry Neil Kaufman) Adverbs of Reason An adverb of reason gives a reason for the main idea. An adverb of reason usually starts with a subordinating conjunction like "as," "because," "given," or "since." I don't have a bank account because I don't know my mother's maiden name. (Comedian Paula Poundstone) Since we cannot change reality, let us change the eyes which see reality. (Greek author Nikos Kazantzakis) Why Should I Care about Adverbs? Here are the six most common writing issues related to adverbs. (Issue 1) Use adverbs ending "-ly" sparingly. Professional writers (particularly fiction writers) don't like adverbs that end "-ly." They consider them unnecessary clutter. If you were to attend a fiction-writing course, you would be taught to craft words that render "-ly" adverbs redundant. On that course, you would undoubtedly be shown this quote: The road to hell is paved with adverbs. (Author Stephen King) As Stephen King advocates, if you choose the right verb or the right dialogue, you don't need an adverb. Compare these two examples: Extremely annoyed, she stared menacingly at her rival. (Critics on that course would trash this.) Infuriated, she glared at her rival. (This is far sharper.) Here are the three good reasons to kill a "-ly" adverb: (1) The adverb is a tautology (i.e., needless repetition of an idea). She smiled happily. (2) The adverb is "spoon feeding" the reader. She smiled disappointedly. (By the time your readers reach this sentence, they should know from context that it's a disappointed smile. The trick is to show them, not literally tell them, that she's disappointed. It's far more engaging. Less is more.) Spoon-feeding with an adverb happens most commonly with verbs like said, stated, and shouted (known as verbs of attribution). "Ow, pack that in," Rachel shrieked angrily. (You can scrap the adverb if it's implicit from the dialogue or context.) (3) The adverb is only there because of a badly chosen verb. Sitting dejectedly in its cage, the parrot looked utterly unhappy. (This would cause a click-fest as those critics armed their red pens.) Looking miserable, the parrot lay on the floor of its cage. (This is sharper. Your readers will know that parrots don't ordinarily lie on the floor.) Avoiding adverbs is a self-imposed restraint that many writers follow. It's like a game. Upon completing their work, professional writers will often do a text search for "ly " (note the space) to find adverbs and to re-justify their use before submission. Remember though that if your adverb is part of the story, keep it. Your son is surprisingly handsome. (Issue 2) Delete "very" and "extremely." Professional writers hate adverbs such as "extremely," "really," and "very" (called intensifiers). For them, using an intensifier demonstrates a limited vocabulary. It's a fair point. If you choose the right words, you can avoid intensifiers. Don't write… Go for something like… very bad atrocious extremely hungry ravenous really old ancient incredibly tired exhausted Many writers assert that intensifiers are so useless, you should delete them even if you can't find a more descriptive word. Ireland is great for the spirit but very bad for the body. (Actor Hugh Dancy) (The deletion kills a word but no meaning.) Writer Mark Twain shared this view: Substitute "damn" every time you're inclined to write "very". Your editor will delete it, and the writing will be just as it should be. Here's a good tip. Press "CTRL H". Put "very" in the Find box. Put nothing in the Replace box. Click Replace All. (Issue 3) When an adverb modifies an adjective, don't join them with a hyphen. When an adverb modifies an adjective, don't join the two with a hyphen. I don't sleep with happily married men. (Actress Britt Ekland) Ironically, he described himself as "a professionally-qualified grammarian". (Don't join the adverb and the adjective with a hyphen.) Remember that not all adverbs end "-ly." The beginning is the most-important part of the work. (translation of Greek philosopher Plato) As covered next, this no-hyphen rule applies only to adverbs that are obviously adverbs (e.g., ones that end "-ly"). (Issue 4) When an adverb that could feasibly be an adjective modifies an adjective, use a hyphen. A few adverbs (e.g., "well" and "fast") look like adjectives. To make it clear your adverb is not an adjective, you can link it to the adjective it's modifying with a hyphen. The hyphen says "these two words are one entity," making it clear they're not two adjectives. She's a well-known dog. (The hyphen makes it clear that the dog is famous (i.e., well-known) as opposed to well (i.e., healthy) and known (i.e., familiar).) He sold me six fast-growing carp. (The hyphen makes it clear the carp are ones that grow quickly and not growing ones that can swim quickly.) This issue crops up occasionally with "well," and "well" is almost never used as an adjective (meaning healthy) in a chain of other adjectives. So, in real life, there's almost never any ambiguity caused by these adjectivey-looking adverbs. Therefore, the following rule will cover 99% of situations: use a hyphen with "well" when it precedes an adjective. It's a well-known tactic. (This is not really about avoiding ambiguity. It's more about protecting readers from a reading-flow stutter caused by the feasibility of ambiguity.) It's a widely known tactic. (Don't use a hyphen with normal adverbs. They don't cause reading-flow stutters.) Read about hyphens in compound adjectives. (Issue 5) Make it clear what your adverb is modifying. Whenever you use an adverb (a single-word or multi-word one), do a quick check to ensure it's obvious what it refers to. Here are some examples of badly placed adverbs. Singing quickly improved his stammer. (It's unclear whether quickly modifies singing or improved. This is called a squinting modifier.) Peter told us after Christmas that he plans to diet. (Here, after Christmas sits grammatically with told but logically with plans. This is called a misplaced modifier.) I recorded the hedgehog feeding its hoglets cautiously. (It's unclear whether cautiously modifies recorded or feeding.) Usually a badly placed modifier can be fixed by putting it nearer to the verb it's modifying. (The top two examples can be fixed by moving the shaded text to the end. The third can be fixed by moving "cautiously" either to the left of "recorded" or to the left of "feeding," depending on the intended meaning.) Read more about squinting modifiers. Read more about misplaced modifiers. It's worth mentioning limiting modifiers (e.g., "hardly," "nearly," "only") because these commonly create logic flaws or ambiguity. I only eat candy on Halloween. No lie. (Actor Michael Trevino) (Logically, this means all he does on Halloween is eat candy; therefore, he doesn't work, sleep, or drink on that day. In everyday speech, we all get away with misplacing "only," but we should try to be more precise in our writing.) I eat candy only on Halloween. (This is sharper. As a rule of thumb, the best place for "only" is never to the left of a verb.) The two examples below are correct, but they mean different things. Lee copied nearly all 10 of your answers. (This tells us Lee copied most of the answers.) Lee nearly copied all 10 of your answers. (Here, Lee might have copied none to nine.) It's worth spending a second to ensure your limiting modifiers are well positioned. (Issue 6) Use a comma after a fronted adverbial. When an adverbial phrase or clause is at the start of a sentence, it is usual to follow it with a comma. In colonial America, lobster was often served to prisoners because it was so cheap and plentiful. One April day in 1930, the BBC reported, "There is no news." If you're called Brad Thor, people expect you to be 6 foot 4 with muscles. (Author Brad Thor) When the adverbial is at the back, the comma can be left out. Each of these could be rewritten without comma and with the shaded text at the end. When the adverbial is at the front, it's not a serious crime to omit the comma, but you should use one because it aids reading. When the adverbial is short (one or two words), your readers won't need helping, so you're safe to scrap the comma if you think it looks unwieldy. Yesterday I was a dog. Today I'm a dog. Tomorrow I'll probably still be a dog. Sigh! There's so little hope for advancement. (Cartoonist Charles M. Schulz via Snoopy) Read more about adverbial phrases. Read more about adverbial clauses. Key Points Try to render adverbs ending "-ly" redundant with better word choice. Have you used "very"? Yes? Delete it. Don't join an adverb to an adjective unless that adverb is "well." Put your adverbs close to what they're modifying and far from what they're not.