English Victorian Literature - Shaw - Mrs Warren's Profession - The Great Social Evil

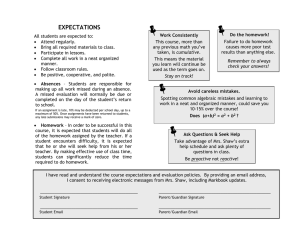

advertisement

1 Essay question: How does Shaw's social criticism link the "Great Social Evil" to capitalism and the question of social responsibility? As of the middle of the nineteenth century, Britain witnessed not only the peak of the Industrial Revolution but also a surge of both prostitution and the awareness of it as a social problem, especially in urban centres. 1 One common term to refer to the issue of prostitution was “The Great Social Evil”, which conveys the demonisation of sex workers, who were commonly considered as detrimental to the moral and virtue of society. Therefore, prostitutes were stigmatised and often served as scapegoats for the spread of sexually transmitted diseases, such as tuberculosis, and were generally treated as personifications of temptation and vice. 2 They fulfilled the stereotype of the “fallen woman”, and thus, the vast majority of middle- and upper-class people did not question these allegations, but made the prostitutes themselves responsible for their bad social position. George Bernard Shaw’s 1893 play Mrs Warren’s Profession provides a point of view radically opposed to that of many of his contemporaries, placing a prostitute in the centre of the story and giving a less superficial explanation for her situation than many other social critics. This essay will examine how Shaw’s social criticism views the “Great Social Evil” in the light of unrestricted capitalism, the unresolved status of the “Woman Question”, and the question of social responsibility. One point of criticism in the play is the duality of moral standards. In the late nineteenth century, it was still widely accepted that men who broke moral rules were not sanctioned as strictly as women who committed the same alleged indecencies. Shaw satirically points out this problem in Frank’s seemingly playful seduction of Mrs Warren. Even though Frank provokes her kiss and refuses to back off after she warns him of keeping flirting (‘Cant help it, my dear Mrs Warren: it runs in the family’)3, he afterwards blames her for her moral transgression: ‘Viv: your mother’s impossible. […] she’s a bad lot, a very bad lot’. 4 The blaming of Mrs Warren for a socially unacceptable act that involves him to the same extent is a handy excuse for Frank. This selfrighteous way of dealing with guilt is only open to him because of his gender in Victorian society. 1 Fraser Joyce, ‘Prostitution and the Nineteenth Century: In Search of the “Great Social Evil”’, Reinvention: an International Journal of Undergraduate Research, 1 (2008), warwick.ac.uk/fac/cross_fac/iatl/reinvention/ archive/volume1issue1/joyce [Accessed 06 December 2020]. 2 W. R. Rogers, ‘The Great Social Evil.’, The Lancet, 71 (1858, republ. ), 568, doi.org/10.1016/S01406736(02)20676-5 [Accessed 03 December 2020]. 3 George Bernard Shaw, Mrs Warren’s Profession, in The Norton Anthology of English Literature, vol. E, tenth edition, ed. by Stephen Greenblatt et al. (1962; repr. New York: Norton, 2018), 873-919, p. 885. 4 Shaw, Mrs Warren, p. 902. 2 According to Anderson, the moral double standards for men and women were based on a widespread woman image depicting women as morally inferior to their male counterparts. This view was justified with the claim that men, allegedly being capable of thinking more rationally, had better control of their sexual impulses than women, which was said to result in more moral behaviour. However, contemporary social critic John Stuart Mill criticised the argument of female moral inferiority, explaining that the evidence for women’s irrationality was a consequence of a lack of higher education, which was denied to many women. Mill, as quoted in Anderson, rejected the argument, stating that the conventional way of raising girls to domestic, obedient and intellectually inactive wives was ‘“artificial”’, i.e. socially constructed.5 The strict measures against prostitution enforced by the Contagious Diseases Act once again exemplify the double standards of Britain in Shaw’s time. While the sexual transgression of men who slept with prostitutes was blamed on the ill-natured seduction through sex workers6, the latter were the only ones suffering from the enforcement of the Act and its extensions. Their clients were not subjected to such discriminatory laws. Some feminist organisations, recognising the injustice of this harassment, rallied against the Act, demanding to repeal the measures because of their one-sidedness. Walkowitz writes that these feminist activists ‘rejected the prevailing social view of “fallen women” as pollutants of men and depicted them instead as victims of male pollution’. 7 Even though these movements revolutionised the public discourse about prostitution, they represented only an intellectual, emancipated minority standing at the start of the larger international feminist movement. Besides giving rise to the acceptance of double standards, the supposed intellectual and moral inferiority of women had far-reaching consequences for their professional lives, as it placed ‘artificial constraints placed on women’s social and economic activity’.8 Women were not thought fit for most professions that required a formal education, leaving only certain branches of massively underpaid manufacturing labour for most working-class women. The “Woman Question”, which emerged in the middle of the Victorian period, refers to the problem of large-scale female unemployment as well as the exploitation of women in factories. Mrs Warren, having a workingclass background, thus justifies her becoming a prostitute with the material need of sustaining a 5 Amanda Anderson, ‘Mid-Victorian Conceptions of Character, Agency, and Reform: Social Science and the “Great Social Evil”’, Tainted Souls and Painted Faces: The Rethoric of Fallenness in Victorian Culture, (New York: Cornell University Press, 1983), 22-65, p. 37-41. 6 Rogers, p. 568. 7 Judith R. Walkowitz, ‘Male Vice and Feminist Virtue: Feminism and the Politics of Prostitution in Nineteenth-Century Britain’, History Workshop Journal, 13 (1982), 79-93, doi.org/10.1093/hwj/13.1.79 [Accessed 03 December 2020], p. 80. 8 Walkowitz, p. 81. 3 minimum standard of living. She vehemently rejects Vivie’s notion that ‘Everybody has some choice’9, upholding that her ‘circumstances’ prevented her from taking a more tolerated employment. As an example of the exploitation and unbearable working conditions of women working in the industrial sector, she tells the story of her half-sister, a young woman trying to stay ‘respectable’ by working in a chemical factory ‘twelve hours a day for nine shillings a week until she died of lead poisoning’.10 Albeit describing an exaggeratedly tragic case, the destiny of her halfsister resembles the lives of thousands of real female factory workers suffering from overwork and underpayment: Ada Nield Chew, a young factory worker in 1884, complains about the enormous amount of working hours required to earn a ‘dying wage’11, a term she uses to emphasise that factory workers cannot lead a humane life can be led with wages barely sufficient to afford food. The anonymous author of the letter ‘The Great Social Evil’ claims to be from a similar background as Chew, but in contrast to her, she reports of her entering the prostitution business in order to achieve a better living standard. She describes prostitutes’ decision to sell their bodies as their last resort from starvation or death in the factories: ‘“Render up your body or die”’. 12 In a similar manner, Mrs Warren recognises her moral dilemma when she says, ‘I was more afraid of the whitelead factory than I was of the river’13: there is social acceptance for factory workers who are in a constant struggle for subsistence, but her material need for a humane standard of living requires more money than she can earn in the socially acceptable jobs available to her. Therefore, being aware of the cruel working conditions in manufacturing, and being prevented from exerting other professions through the social limitations of female work, Mrs Warren sees her only chance to escape the existential threat of poverty in becoming a prostitute, regardless of the consequences for her social status. Despite the majority of critics relied on the traditional image of women, there were some early voices calling for change. Mill identifies the limited access of women to the labour market as the key problem underlying the high prostitution rates. 14 By having the character of Mrs Warren echo the justifications of prostitutes for their profession eloquently, Shaw confronts his 9 Shaw, Mrs Warren, pp. 894-95. ‘The Great Social Evil’, Correspondence with the Times, (24 February 1858), in The Norton Anthology of English Literature, vol. E, ed. by Julia Reidhead and Marian Johnson (1962; repr. New York: Norton, 2018), 666-670, p. 669. 11 Ada Nield Chew, ‘A Living Wage for Factory Girls at Crewe, 5 May 1884’, in The Norton Anthology of English Literature, vol. E, ed. by Julia Reidhead and Marian Johnson (1962; repr. New York: Norton, 2018), 652-53, p. 653. 12 ‘The Great Social Evil’, Correspondence with the Times, (24 February 1858), in The Norton Anthology of English Literature, vol. E, ed. by Julia Reidhead and Marian Johnson (1962; repr. New York: Norton, 2018), 666-670, p. 669. 13 Shaw, Mrs Warren, p. 895. 14 John Stuart Mill, The Subjection of Women (1869; republ. London: The Electric Book Company, 2001), ProQuest Ebook Central, pp. 119-20, ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/abdn/detail.action?docID=3008446 [Accessed 03 December 2020]. 10 4 audience with a macro-sociological perspective on the “Great Social Evil”. He transparently demonstrates how the socially constructed limitations of women’s opportunities cause grinding poverty among the lower class, which in turn contributes to the large-scale retorting to prostitution by young women. At the same time, Shaw depicts prostitutes as morally conscious beings, a notion starkly contrasting the public opinion about them. Through Mrs Warren’s moral justification, Shaw implicitly challenges the morality of the established gender roles. One major instance hereof is Mrs Warren’s questioning the justice of condemning prostitutes for sleeping with men outside of the legal frame of marriage: What is any respectable girl brought up to do but to catch some rich man’s fancy and get the benefit of his money by marrying him?—as if a marriage ceremony could make any difference in the right or wrong of the thing! Oh, the hypocrisy of the world makes me sick!15 Shaw compares the prostitute to the married woman in an unconventional manner, claiming that both women essentially give up their sexual chastity to achieve access to the man’s financial resources. By proposing the striving for financial gain as the common motivation of both prostitution and marriage, Shaw reverts the argument outlawing prostitution as immoral, instead questioning the validity of the established moral standards. In this particular point, Shaw’s criticism resembles very closely Augusta Webster’s stance expressed through the narrating voice in ‘A Castaway’. The prostitute here, too, asks the rhetorical question, ‘what have they [i.e., married wives, note by the editor] done, / what borne, to prove them other than we are?’ 16 Both authors show the arbitrariness of morality in their society. Proceeding from this insight, they criticise moral conventions more deeply: when Mrs Warren tells Vivie that ‘it’s only good manners to be ashamed of [prostituting oneself, note by the editor]’ 17, she indicates that morality is merely acted out according to a set of rules and expectations. Shaw hereby criticises that not morality but social acceptance is the key motivation for people to adhere to social rules. This applies to the condemnation of prostitution as well as to any other aspect of morality. Vivie expresses the criticism of morality as a mere tool of establishing social recognition concisely: ‘I know very well 15 Shaw, Mrs Warren, p. 896. Augusta Webster, ‘A Castaway’, Portraits, 2nd ed. (London: Macmillan and Co., 1870), 35-62, ll. 132-33, Canadian Poetry Online, rpo.library.utoronto.ca/poems/castaway-0 [Accessed 03 December 2020]. 17 Shaw, Mrs Warren, p. 897. 16 5 that fashionable morality is all a pretence’. 18 The term ‘fashionable’ gives the argument an ironic undertone, suggesting that the fundamental principles of ethics are wrongly treated as volatile accessories of etiquette by the middle- and upper-classes. By the Victorian period, capitalism was widely considered the best possible economic model.19 The discrepancy between moral ideals and actual behaviour was very pronounced in capitalists’ justification of their exploitation of the working class which contrasted their selfdepiction as morally superior. As an aristocrat and capitalist, Crofts impersonates these contradictions in the play. His moral leading principle can be illustrated using a quote: when Vivie criticises him for his participation in the exploitation of prostitutes, he openly admits that ‘society doesnt ask any inconvenient questions; and it makes precious short work of the cads who do’. 20 Here, Shaw points out that the upper classes aim to maintain a morally impeccable appearance only outwardly, knowing that they will not be sanctioned by society for any kind of concealed misconduct. Considering the issue of prostitution, this code of conduct does not elicit invariably ethical behaviour but is based on hypocrisy. In addition to the pretentious morality of the higher classes, Shaw criticises the fact that inhumane economic practices in the shape of unregulated capitalism are considered morally acceptable. As Crofts states, he has ‘an honest belief that things are making for good on the whole’21, which is obviously a reference to his anti-regulatory economic views. His support of unregulated market economies could be inspired by Adam Smith’s popular ‘invisible hand’ theory, which states that the desire of every actor in the economy is to maximise their profits, which eventually precipitates the improvement of the economic situation of society as a whole.22 By adopting this economic philosophy, Crofts ignores his responsibility for the poor living conditions of his working-class employees, silencing his conscience with the anticipation of the general good his low-wage policy allegedly contributes to. In reality, many of the biggest employers of cheap workers were factory owners who lived in spatial and ‘social segregation’ from the working-class.23 Therefore, they had hardly any direct contact to the workers and their living conditions, which facilitated their flimsy justifications for paying inadequate wages. By artificially keeping their workforce short on money, they indirectly forced them into prostitution. Through their 18 Shaw, Mrs Warren, p. 917. Geoffrey Russel Searle, Morality and the Market in Victorian Britain, (1998, republ. Oxford Scholarship Online: Oxford, 2011), p. 2, doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780198206989.001.0001 [Accessed 03 December 2020]. 20 Shaw, Mrs Warren, p. 906. 21 Shaw, Mrs Warren, p. 903. 22 Emma Rothschild, ‘Adam Smith and the Invisible Hand’, The American Economic Review, 84 (1994), 319-22, p. 319. 23 Searle, p. 6. 19 6 control of working-class wages, the wage policies of richest members of society had a fundamental influence on the living realities of the poorest. When Vivie, seeing the interconnection of low wages and prostitution, ironically attacks Croft’s idea of promoting social justice through economic egoism, Crofts restates his refusal to accept his social responsibility as the person in charge of his workers’ living conditions: for him, it is ‘Not ourselves [i.e. the upper-class, note of the editor], of course.’24 whose task it is to create fair labour policies. Various contemporary voices criticise the rejection of social responsibility represented by Crofts. The author of ‘The Great Social Evil’ holds society responsible for creating the grievances that forced her into prostitution: ‘If I am a hideous cancer in society, are not the causes of the disease to be sought in the rottenness of the carcass?’. 25 She metaphorically accuses the other classes of moral debauchery for allowing the emergence of the poverty threatening the workingclass. She furthermore laments the fact that people of better social standing are not willing to offer their assistance to prostitutes, suggesting that the other classes knowingly contribute to the miserable position of sex workers: ‘the great gulf you have dug and keep between yourselves and the dregs’.26 The imagery of spatial separation from the prostitutes may allude to both the other classes’ responsibility for the social position of prostitutes and their self-perception as the morally superior groups. The anonymous writer of another letter on the issue of prostitution criticises the moral double standards applied by the upper-class. He says that ‘So long as a man, living in known vice, is at home in society, in families, in the Cabinet, or in Parliament, matters must run on as formerly’27, identifying the uncontested acceptance of structural injustice as the main cause of the high prostitution rates. In conclusion, in Mrs Warren’s Profession, Shaw exerts social criticism relating to the issue of prostitution along four interlocking key factors. Firstly, he refutes the notion that women were morally inferior to men. Secondly, Shaw shows the detrimental implications of Victorian gender roles for women’s employment opportunities and links their limited professional perspective to the financial compulsion of prostitution. Thirdly, he examines the contradictory double standards of morality of the allegedly morally superior social classes towards sex workers. Finally, he criticises capitalists’ ignorance of their responsibility for the social grievances leading to the massive numbers of prostitutes of Victorian Britain. 24 Shaw, Mrs Warren, p. 903. ‘The Great Social Evil’, p. 668. 26 ‘The Great Social Evil’, p. 669. 27 ‘The Greatest Social Evil’, Tait’s Edinburgh Magazine (Edinburgh, February 1858), 110-14, p. 110. 25 7 Word count: 2,736 List of References Primary Texts Shaw, George Bernard. Mrs Warren’s Profession, in The Norton Anthology of English Literature, vol. E, tenth edition, ed. by Stephen Greenblatt et al. (1962; repr. New York: Norton, 2018), 873919 Webster, Augusta, ‘A Castaway’, Portraits, 2nd ed. (London: Macmillan and Co., 1870), 35-62, Canadian Poetry Online, rpo.library.utoronto.ca/poems/castaway-0 [Accessed 03 December 2020] Secondary Texts Anderson, Amanda, ‘Mid-Victorian Conceptions of Character, Agency, and Reform: Social Science and the “Great Social Evil”’, Tainted Souls and Painted Faces: The Rethoric of Fallenness in Victorian Culture, (New York: Cornell University Press, 1983), 22-65 Chesterton, Gilbert Keith, George Bernard Shaw (1909, republ. Project Gutenberg, 2006), https://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/19535 [Accessed 03 December 2020] Joyce, Fraser, ‘Prostitution and the Nineteenth Century: In Search of the “Great Social Evil”’, Reinvention: an International Journal of Undergraduate Research, 1 (2008), warwick.ac.uk/fac/cross_fac/iatl/reinvention/archive/volume1issue1/joyce [Accessed 06 December 2020] Laite, Julia, ‘Women, Prostitution and Work’, Journal of Women’s History, 29 (2017), 169-74 Mill, John Stuart, The Subjection of Women (1869; republ. London: The Electric Book Company, 2001), ProQuest Ebook Central, ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/abdn/detail.action?docID=3008446 [Accessed 03 December 2020] 8 Rogers, W. R., ‘The Great Social Evil.’, The Lancet, 71 (1858, republ. Science Direct, 2003), 568, doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(02)20676-5 [Accessed 03 December 2020] Rothschild, Emma, ‘Adam Smith and the Invisible Hand’, The American Economic Review, 84 (1994), 319-22 Searle, Geoffrey Russel, Morality and the Market in Victorian Britain, (1998, republ. Oxford Scholarship Online: Oxford, 2011), doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780198206989.001.0001 [Accessed 03 December 2020] ‘The Great Social Evil’, The Lancet, 71 (1814, republ. Science Direct, 2013), 568, doi.org/10.1016/ S0140-6736(02)20676-5 [Accessed 03 December 2020] ‘The Greatest Social Evil’, Tait’s Edinburgh Magazine (Edinburgh, February 1858), 110-14 The Norton Anthology of English Literature, vol. E, ed. by Julia Reidhead and Marian Johnson (1962; repr. New York: 2018) Walkowitz, Judith R, ‘Male Vice and Feminist Virtue: Feminism and the Politics of Prostitution in Nineteenth-Century Britain’, History Workshop Journal, https://doi.org/10.1093/hwj/13.1.79 [Accessed 03 December 2020] 13 (1982), 79-93,