Palestine Mapping Controversy: Letters to Harper's Magazine

advertisement

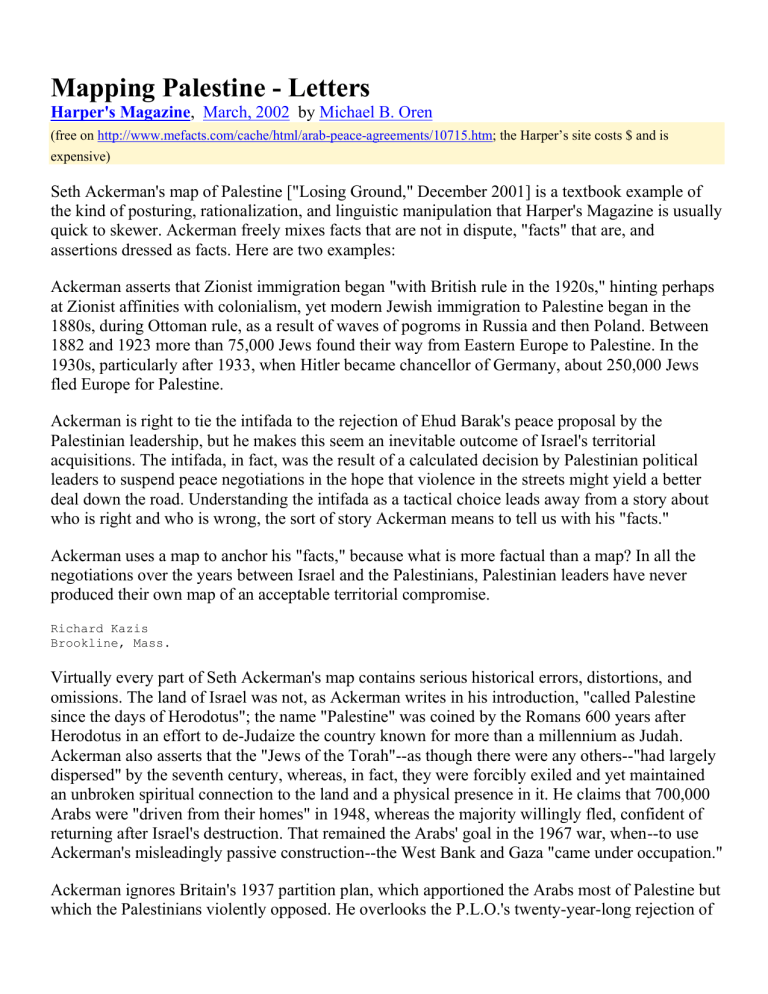

Mapping Palestine - Letters Harper's Magazine, March, 2002 by Michael B. Oren (free on http://www.mefacts.com/cache/html/arab-peace-agreements/10715.htm; the Harper’s site costs $ and is expensive) Seth Ackerman's map of Palestine ["Losing Ground," December 2001] is a textbook example of the kind of posturing, rationalization, and linguistic manipulation that Harper's Magazine is usually quick to skewer. Ackerman freely mixes facts that are not in dispute, "facts" that are, and assertions dressed as facts. Here are two examples: Ackerman asserts that Zionist immigration began "with British rule in the 1920s," hinting perhaps at Zionist affinities with colonialism, yet modern Jewish immigration to Palestine began in the 1880s, during Ottoman rule, as a result of waves of pogroms in Russia and then Poland. Between 1882 and 1923 more than 75,000 Jews found their way from Eastern Europe to Palestine. In the 1930s, particularly after 1933, when Hitler became chancellor of Germany, about 250,000 Jews fled Europe for Palestine. Ackerman is right to tie the intifada to the rejection of Ehud Barak's peace proposal by the Palestinian leadership, but he makes this seem an inevitable outcome of Israel's territorial acquisitions. The intifada, in fact, was the result of a calculated decision by Palestinian political leaders to suspend peace negotiations in the hope that violence in the streets might yield a better deal down the road. Understanding the intifada as a tactical choice leads away from a story about who is right and who is wrong, the sort of story Ackerman means to tell us with his "facts." Ackerman uses a map to anchor his "facts," because what is more factual than a map? In all the negotiations over the years between Israel and the Palestinians, Palestinian leaders have never produced their own map of an acceptable territorial compromise. Richard Kazis Brookline, Mass. Virtually every part of Seth Ackerman's map contains serious historical errors, distortions, and omissions. The land of Israel was not, as Ackerman writes in his introduction, "called Palestine since the days of Herodotus"; the name "Palestine" was coined by the Romans 600 years after Herodotus in an effort to de-Judaize the country known for more than a millennium as Judah. Ackerman also asserts that the "Jews of the Torah"--as though there were any others--"had largely dispersed" by the seventh century, whereas, in fact, they were forcibly exiled and yet maintained an unbroken spiritual connection to the land and a physical presence in it. He claims that 700,000 Arabs were "driven from their homes" in 1948, whereas the majority willingly fled, confident of returning after Israel's destruction. That remained the Arabs' goal in the 1967 war, when--to use Ackerman's misleadingly passive construction--the West Bank and Gaza "came under occupation." Ackerman ignores Britain's 1937 partition plan, which apportioned the Arabs most of Palestine but which the Palestinians violently opposed. He overlooks the P.L.O.'s twenty-year-long rejection of Resolution 242 (Israel accepted it) and the refusal of most Arab leaders even to negotiate with Israel. He notes Israel's objection to re-admitting Palestinian refugees but neglects Israel's 1949 offer to resettle 100,000 refugees and to compensate the rest as part of a peace settlement that the Arabs universally rejected. He stresses the "building" of Israeli settlements in the territories since the 1993 Oslo Accords--in fact, existing settlements were thickened in conformity with those agreements--but fails to cite the P.L.O.'s relentless incitement and arming of the Palestinian population in flagrant violation of the accords. Most egregiously, Ackerman omits any word of the Palestinian terror that has taken 248 Israeli lives since the outbreak of the intifada. Ackerman reproduces a map of a truncated Palestinian state allegedly proposed by Israelis in 2000. In fact, Israel finally offered to withdraw from at least 90 percent of the West Bank and to make up the difference with Israeli territory, to relocate 50,000 settlers, and to divide sovereignty over Jerusalem. This unprecedented package, including a viable solution to the refugee problem, elicited no Palestinian response other than suicide bombings. The Palestinian leadership insisted on provisions that would have inundated Israel with refugees and thus destroyed it demographically. The peace process collapsed not over land but because of the Palestinians' refusal to accept Israel's existence. Historically, it has been that refusal, rather than Israel's resistance to compromise, that has led to the Palestinians "losing ground." Cleaving to it will only cost them more. Michael B. Oren Senior Fellow The Shalem Center Jerusalem Seth Ackerman responds: I did not claim that Zionist immigration to Palestine began in the 1920s; I wrote that "a wave of Zionist immigration" began with the 1920 British mandate. "Palestine" was indeed the term used by Herodotus to denote the land we now call either Palestine or Israel. More pertinent to presentday troubles is the matter of the 700,000 Palestinian Arabs who fled during the 1948 war. As with other instances of twentieth-century political mass expulsion, the Palestinian exodus still has its coterie of deniers. The uprooting happened spontaneously, they insist, or by some other deus ex machina device--"a miraculous clearing of the land," as Chaim Weizmann, Israel's first president, mystically put it. We find a different account in Israeli government archives: "At least 55 percent of the total of the exodus was caused by our operations," estimated an Israeli army intelligence document dated June 30, 1948, and headed "The emigration of Palestinian Arabs in the period 1/12/1947-1/6/1948." It judged an additional 15 percent to have been the work of the other Jewish paramilitaries and 22 percent to have been caused by a general Palestinian "crisis of confidence." According to the document, only about 5 percent of the Arabs fled because their leaders told them to. "There were some fellows who refused to take part in the expulsion action," then-general Yitzhak Rabin recalled in a censored passage of his 1979 memoirs. "Prolonged propaganda activities were required after the action, to remove the bitterness of these [soldiers] and explain why we were obliged to undertake such a harsh and cruel action." This was the seminal dilemma of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict: What Israel's founders desired--a democratic Jewish state in Palestine--required a Jewish majority. Yet less than a third of the population was Jewish. There was only one durable solution, as the head of the Jewish National Fund's Lands Department perceived as early as 1940: "It must be clear," wrote Yosef Weitz, "that there is no room in the country for both people ... The only solution is a Land of Israel, at least a western Land of Israel, without Arabs. There is no room here for compromise.... There is no way but to transfer the Arabs from here to the neighboring countries.... Not one village must be left, not one [Bedouin] tribe." The result has been fifty years of war. COPYRIGHT 2002 Harper's Magazine Foundation COPYRIGHT 2002 Gale Group