Grant Era & New South: Reconstruction, Scandals, & Politics

advertisement

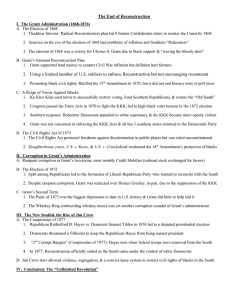

THE GRANT ERA AND THE NEW SOUTH In 1868, the Republican Party nominated General Ulysses S. Grant, the foremost northern military hero of the Civil War, as their candidate for President. The Democratic candidate was former New York Governor Horatio Seymour, a strong opponent of Radical Reconstruction. Grant defeated Seymour, but in what proved to be a surprisingly close election, perhaps the result of public uneasiness at Grant's political inexperience or growing dissatisfaction with the Radical Republicans in the wake of the attempt to impeach President Andrew Johnson. In truth, Grant was inexperienced. A career soldier who had proven unsuccessful in business during a short pre-war civilian career, he had never before held an elective office. He relied heavily on party leaders for guidance, and, not surprisingly, came to support Radical Reconstruction. He also relied on a number of personal friends and army subordinates, whom he appointed to high ranking government positions. He also proved to be an able practitioner of the "Spoils System," rewarding political supporters with government jobs, a policy which critics labeled "Grantism." All of these factors led to accusations of corruption and favoritism. One incident that could have erupted into a major scandal took place early in his administration. In what became known as "Black Friday," a group of speculators headed by noted financiers James Fisk and Jay Gould, using insider information and influence from government officials and Grant's own brother-in-law, managed to corner the limited available market on gold, driving the prices up and making huge profits. When Grant found out what was happening, he authorized the sale of four million dollars in gold from the Treasury, driving the price back down and thwarting the speculators. Although some blamed the incident on Grant's reliance on the Spoils System, others praised his personal integrity in breaking up the scheme. Reconstruction continued to dominate the political arena, and, unlike his predecessor, Grant worked well with Congress. He enforced a series of laws known as the “Ku Klux Klan Acts" of 1870 and 1871, using martial law against the Klan and other similar anti-Reconstruction terror groups in South Carolina. Both the Grant and Johnson administrations made notable achievements in the field of diplomacy, which are often overlooked. During the Civil War, the French Emperor Napoleon III had established a puppet government in Mexico in violation of the Monroe Doctrine, knowing that the United States was powerless to stop him. With the war over, the Johnson administration sent troops to the border and issued diplomatic protests, which, combined with internal resistance in Mexico, expelled the French. In 1867, Johnson's Secretary of State, William H. Seward, engineered the purchase of Alaska from Russia for $7.2 million. The purchase was ridiculed at the time as "Seward's Folly" or "Seward's Ice Box," but proved to be a wise acquisition. Grant's administration successfully settled the so-called "Alabama Claims" in 1871. During the Civil War, several ships built in Britain, most notably the Alabama, were sold to the Confederacy for use as "commerce raiders," attacking northern commercial shipping. Unable to recover damages from the defunct Confederacy, the United States sued the British government. American diplomatic pressure forced the British to sign the Treaty of Washington in 1871, agreeing to submit the claims to international arbitration. The following year, an international court in Geneva, Switzerland, ordered Britain to pay $15,500,000 in damages. After a relatively successful first term in office, Grant was renominated in 1872. A group of dissatisfied members of his own party, known as the "Liberal Republicans," broke away from the party and united with the Democrats to support the joint candidacy of famed New York newspaper publisher and editor Horace Greeley. The Liberal Republicans included a diverse alliance of anti-Spoils System reformers, moderates, and disillusioned former Radicals. Greeley, a former abolitionist, supported of a variety of reform movements deemed by many as impractical. With his wispy fringe of chin whiskers, "granny" glasses, wide-brimmed hat and long white coat, he made a perfect target of ridicule in the political cartoons of the day. Grant won in a landslide, and Greeley, unfortunately, died just weeks after the election. However, Grant's second term would not prove as successful as his first, as charges of "Grantism" mounted, and scandal after scandal involving Grant's appointees emerged. Three of the most noteworthy scandals were the Credit Mobilier, the Whiskey Ring, and the Indian Ring. The Credit Mobilier was a dummy, French-incorporated construction company set up to collect government subsidies being awarded to companies contracted to build the Union Pacific Railroad, part of the Transcontinental Railroad. The organizers of the scheme, including a Massachusetts congressman, then bribed other members of Congress and government officials with company stock to forestall an investigation. The fraud had been going on since before Grant took office, but was first brought to public attention during the 1872 election campaign. By the time the investigation was complete, officials implicated included several Congressmen and Grant's vice president, Schuyler Colfax. The Whiskey Ring, which was exposed in 1875, involved distillers bribing Treasury officials for cut-rate tax stamps, and also implicated President Grant's private secretary and former Civil War aide, Orville Babcock. The Indian Ring, exposed in 1876, consisted of trading companies bribing the War Department to secure appointments to run Indian trading posts in the West. Secretary of War William Belknap, a former Civil War general and friend of President Grant, was impeached for his part in the scandal. Although not the President's fault, another event which caused his popularity to decline was an economic depression known as the Panic of 1873. One of the nation's largest investment houses, Jay Cooke & Co., over-invested in railroads and collapsed, dragging with it scores of other investment companies and banks. The nation entered a four-year depression. The economic hard times inspired calls for more paper money, "Greenbacks," to be issued to inflate the economy. By 1875, Congress passed the Specie Resumption Act, requiring a gold standard and a gradual reduction in greenbacks. For the next two decades, "hard money" (a strict gold standard) and softer money (paper currency, credit and a greater use of silver in the nation's money reserve) would be a major political issue. By the mid-1870s, several factors led to a growing abandonment of Reconstruction. The Panic of 1873 certainly drew public attention away from the issue of reconstructing the South. Many Northerners were losing interest, wishing to put the Civil War and its concerns behind them. The election of 1872 had mostly completed the dissolution of the Radical Republicans as a national force, and many felt that with the readmission of all southern states, the process of Reconstruction was complete. In the South, most southern whites had regained the vote by 1872, and set about wresting control of state governments from the "Carpetbaggers," "Scalawags," and blacks, a process known as “Redemption.” To do this, they used their votes, economic pressure, and often intimidation and violence through groups like the Ku Klux Klan. In 1874, partly due to growing Democratic power in the South, that party gained control of the U.S. House of Representatives for the first time since 1861. By 1876, seven of the eleven former Confederate states had been "redeemed." Only Louisiana, South Carolina, and Florida remained under Radical Reconstruction control (the eleventh state, Tennessee, had never had a Radical government). As the next presidential election approached in 1876, both parties nominated moderate northern reformers with strong reputations for integrity. The Republicans nominated Governor Rutherford B. Hayes of Ohio, a former Civil War general, and the Democrats nominated Governor Samuel Tilden of New York, known for his battles against New York City's Tammany Hall political machine. When the election was over, Tilden won the popular votes, and also appeared to have captured the close electoral votes. However, four states--the three "unredeemed" southern states plus Oregon--submitted disputed sets of electoral votes, so no official winner could be proclaimed. Hayes would need to be awarded all of the disputed votes to win the election, and there was no clear Constitutional procedure to deal with the situation. Finally, Congress established a special Electoral Commission composed of five Senators (all Republicans), five members of the House (all Democrats), and five Supreme Court Justices (two Democrats, 2 Republicans, and one independent) to settle the matter. Not until two days before the scheduled inauguration did the Commission decide eight to seven in favor of giving all disputed votes to Hayes, the one "neutral" vote swinging to the Republican side. Some observers predicted the result could ignite a second Civil War, but Tilden graciously stepped aside, and Democratic leaders acquiesced to Hayes's election. It soon became obvious that some kind of "deal" had been struck by leaders of both parties. A persistent legend tells that the Democrats agreed to give the Republicans the White House in return for withdrawing the last federal troops from the South, but the reality was more complicated. Hayes had already publicly stated his intention to withdraw the troops. In fact, in a series of complex arrangements known as the "Compromise of 1877," Republican leaders agreed to insure that a Southerner would sit in Hayes's cabinet, that a number of other government appointments would go to Southerners, and that a larger share of federal funding for internal improvements would go to the South, most notably for the Texas & Pacific Railroad. It was ironic that the election of probably one of the most honest presidents was secured by a "back room deal," a fact which subjected Hayes to unfair charges of corruption. As he had promised, Hayes did withdraw the last troops from the South and attempted to implement a Lincoln-style Reconstruction policy with fairness to both former Confederates and former slaves. Unfortunately, the bitterness of Reconstruction made this impossible. Reconstruction left a mixed legacy. It made possible the passage of the Thirteenth, Fourteenth, and Fifteenth amendments to the Constitution, but in the long run it failed to resolve the race issue or to overcome the bitterness between the North and the South. In the next decades, southern society would become increasingly segregated and discriminatory. If Reconstruction failed to reunite North and South, economic interest achieved greater success in that regard. The old planter aristocracy, which continued to consolidate power after 1877, were known as the "Bourbon Democrats," not after the whiskey, but after the family name of the last kings of France, since they too represented an "old regime" returned to power. Highly conservative, they believed in government with minimal taxation, spending, and services. In this regard, they had much in common with conservative Republican industrial and financial interests in the North, and indeed these two factions often united in opposition to economic reformers, including "Greenbackers" and "Populists," who demanded an inflated money supply and greater government intervention in improving life for poor farmers and working people. Bourbon Democrats and Northern money interests also united in their desire to create a "New South” built on industrialization and championed by southern writers such as Henry Grady. The Bourbons hoped to benefit from an infusion of northern investment in the South, while northern businessmen hoped to take advantage of cheap southern labor. As a result of this partnership, textile manufacturing, using native southern cotton, multiplied nine times between 1880 and 1900. Tobacco processing also became a major industry. Iron and steel production grew until the southern states produced one fifth of the nation's total by 1890. Railroad mileage doubled in the South during the 1880s, and continued to increase afterwards, as demonstrated in Florida by the projects of northern railroad magnates like Henry Flagler and Henry Plant. By the mid-1880s almost all southern railroads of any size operated on the standard gauge. Of course the negative sides to this system were that the South remained largely dependant on the North for its economy, and relatively little of this new wealth filtered down to poor Southerners. The fact that workers were desperate for any money at all and would work for low wages was one factor attracting investment. Much of the workforce in the textile industry for example, was composed of women, who were routinely paid lower wages than men. Blacks filled many jobs in tobacco, iron, and lumber, and drew lower pay than whites. The convict lease system, a system of leasing prisoners to employers, meant that some workers received no pay at all. And if southern industry was on the rise, southern agriculture remained depressed. During Reconstruction, approximately thirty percent of southern farmers were tenants or sharecroppers. By 1900, that figure had risen to seventy percent. In backcountry areas where subsistence farming had once predominated, introduction of cash crops to overcome debt created many of the same problems already affecting the “Deep South.” Industry also exploited the region's resources, such as coal and timber, with no thought of the future. With the end of the Freedman's Bureau and other Reconstruction programs, black southerners were left to their own devices. Many proved remarkably successful, operating small businesses, and excelling in the fields of banking, insurance, medicine, law, and education. Education was key to black success, and the leading black spokesman of the late nineteenth century, Booker T. Washington, emphasized the value of practical, industrial training, as well as the virtues of thrift, manners, and cleanliness. His school, the Tuskegee Institute in Alabama, put these ideas into practice. But southern blacks discovered that they faced challenges to their fundamental rights as well. By the 1880s, an increasing number of states and local jurisdictions passed "Jim Crow" laws, enforcing segregation in everything from education to housing to public transportation, and they seemed to have the backing of the nation's highest courts. In a series of civil rights cases in 1883, the Supreme Court ruled that the Fourteenth Amendment prohibited governments but not private businesses or individuals from discriminating along racial lines. And in the famous Plessy vs. Ferguson case of 1896, the court ruled that separate facilities for blacks and whites were legal as long as they were "equal." By 1900, a variety of voting limitation laws, ranging from poll taxes to property and literacy requirements decreased the black vote by over sixty percent, and the poor white vote by over twenty-five percent. In the famous “Atlanta Compromise” of 1895, Booker T. Washington argued that if blacks would seek economic improvement, political rights would naturally follow. But this argument seemed hollow to many blacks who saw their rights steadily eroded. The beginning of the twentieth century saw black rights at their lowest point since the end of slavery, with strict segregation laws in effect and dissenters facing violence and lynching. And "Jim Crow" laws were not unique to the South, but spread to other areas of the country with sizable black populations as well. The Grant Era and The New South Ulysses S. Grant Soils System/”Grantism” “Black Friday” French in Mexico “Seward’s Folly” Alabama Claims Liberal Republicans Horace Greeley Credit Mobilier Whiskey Ring Indian Ring Panic of 1873 Enforcement Acts/Ku Klux Klan Acts Redemption Compromise of 1877 Bourbon Democrats New South “Jim Crow” Laws Booker T. Washington Atlanta Compromise Lynching Plessy vs. Ferguson Case