Jim Crow and the Ku Klux Klan

advertisement

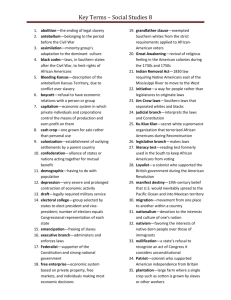

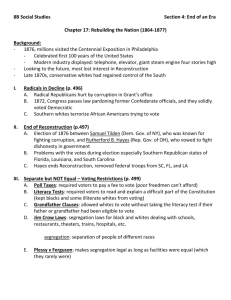

Reconstruction and Its Aftermath: Change in the South Reconstruction Declines During the Grant administration, Northerners began losing interest in Reconstruction as many believed it was too costly and time for the South to solve its own problems. Southerners protested what they called “bayonet rule” – the use of federal troops to support Reconstruction governments. As more freed African Americans moved north, prejudice there grew, and some believed that African Americans should simply return to plantation work in the South. In 1872, Congress closed the Freedman’s Bureau. That same year, it passed the Amnesty Act which pardoned most former Confederates and allowed them to vote and hold office again. Democrats quickly began to regain power across the South. Democrats Regain Power In 1873 a series of political scandals came to light involving the vice president and the secretary of war. At the same time, the nation suffered an economic depression, and blame for the hard times fell on the Republicans and on Grant’s administration in particular. Democrats gained seats in the Senate and won control of the House for the 1st time since before the Civil War. The situation further weakened Congress’s commitment to Reconstruction and protecting the rights of newly freed African Americans. The Election of 1876 The 1876 presidential election between Republican Rutherford B. Hayes and Democrat Samuel Tilden was difficult to decide due to widespread voting fraud. In January 1877, Congress created a special commission of 7 Republicans, 7 Democrats, and 1 Independent to review the election results. The Independent resigned, however, and was replaced with another Republican, so the election was decided in favor of Hayes. The Democrats in Congress threatened to fight the verdict, but they soon struck a deal. In exchange for Hayes becoming president, the federal government agreed to give more aid to the South and also to withdraw all remaining troops from the region. The End of Reconstruction Hayes kept his word, and during a goodwill trip to the South, he announced his intention of letting Southern whites handle their own racial issues. In Atlanta he told an African American audience, “Your rights and interests would be safer if this great mass of intelligent white men were left alone by the general government.” Hayes’s message was clear. The federal government would no longer attempt to reshape Southern society or help Southern African Americans. Reconstruction was over. Redeemer Governments White supremacists, calling themselves Redeemers, regained power in every Southern state. Once in office, the Redeemers reversed improvements made in education by cutting spending for public schools, particularly those open to African-Americans. By the 1880s, only about half of all black children in the South attended school. New legislation drew a “color line” between blacks and whites in public life. Whites called these new acts Jim Crow Laws, an insulting reference to a black character in a popular song. Those who resisted faced the possibility of lynching by groups like the Ku Klux Klan. Once they accomplished their original goals of removing Union troops and putting Democrats back in power, the KKK turned its focus toward maintaining a social order in which whites reigned superior. Unfair Voting Requirements Many states also passed laws requiring citizens who wanted to vote to pay a poll tax. The tax was set high enough to make voting, like schooling, a luxury most blacks could not afford. Some states also required potential voters to pass a literacy test which were difficult for even the well-educated to pass. In theory, poll taxes and literacy tests applied equally to both black and white citizens, but in practice, whites were excused from both by a grandfather clause. This clause exempted citizens whose ancestors had voted before January 1, 1867. Because no African-Americans could vote in the South before that day, the grandfather clause applied only to whites. Plessy v. Ferguson Homer Plessy, a black man arrested for sitting in a whitesonly railroad car in Louisiana, looked to the courts for help. When his case reached the Supreme Court in 1896, however, the justices ruled that segregation was constitutional as long as the facilities provided to blacks were equal to those provided to whites. This “separate but equal” doctrine was soon applied to almost every aspect of life in the South, however these separate facilities were rarely equal. For the next half century, segregation would rule life in the South. Southern Industries Industry in the South made dramatic gains after Reconstruction. Some of the strongest advances were in the textile industry, although tobacco and lumber were also profitable. The iron and steel industry also grew rapidly as well as railroad construction. A cheap and reliable workforce helped Southern industry grow. Sometimes whole families, including children, worked in the factories, although most of these jobs were still off-limits to African Americans. Rural Economies Still, the South did not develop an industrial economy as strong as the North’s, and it remained primarily agricultural. After the war, some plantations were broken up, but many large landowners kept control of their property. When estates were divided, much of the land went to sharecropping and tenant farming, neither of which was profitable. An oversupply of cotton forced prices down, and poor farmers had to buy on credit to get the food and supplies they needed. Sharecropping and overreliance on cotton hampered the development of a more modern agricultural economy, and the rural South sank deeper into poverty and debt.