Uploaded by

Arooj Ejaz

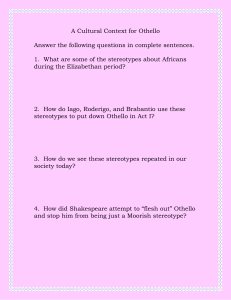

Othello Study Guide: Guthrie Theater Production