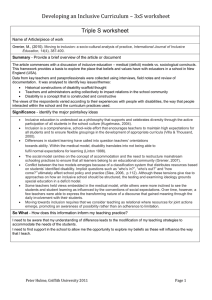

PHILOSOPHY OF INCLUSIVE EDUCATION Inclusive Education Philosophy Participation of students with exceptional needs in inclusive settings is based on the philosophy of equality, sharing, participation and the worth and dignity of individuals. This philosophy is based on the belief that all children can learn and reach their full potential given opportunity, effective teaching and appropriate resources. The Board of Trustees of Palliser Regional Schools supports educating students with special supports and service needs in their regular classrooms in neighbourhood schools as the first placement option, in consultation with students, parents/guardians and school staff. Palliser's mandate reflects this philosophy, and can be found in Board Policy 5 Planning Cycle, Long Term Strategic Plan Palliser Regional Schools agrees that students with exceptional needs must be full participants in school and society. The regular classroom is viewed as the most enabling environment for the student with exceptional needs because of the increased opportunity to participate with same-aged peers without exceptional needs. Inclusion, by definition, refers not merely to setting, but to specially designed instruction and support for students with special supports and service needs in regular classrooms and community schools. Often, meeting the learning needs on either end of the spectrum improves the quality of education for everyone in the classroom, as well as promoting the awareness and acceptance of diversity. INCLUSIVE EDUCATION-PHILOSOPHY, PRINCIPLES, POLICY AND PROGRAMMES “Inclusion is a process. Inclusive education is not merely about providing access into mainstream school for pupils who have previously been excluded. It is not about closing down an unacceptable system of segregated provision and dumping those pupils in an unchanged mainstream system. Existing school systems - in terms of physical factors, curriculum aspects, teaching expectations and styles, leadership roleswill have to change. This is because inclusive education is about the participation of all children and young people and the removal of all forms of exclusionary practice” (Barton, 1998). The murky past in the lives of disabled children has revealed that primitive societies considered them to be wrath of God, symbols of sin or punishment and burden to live in the society. History tells us that they were killed because they were imperfect. During middle ages, these less individuals were brought under the shelter and care of religious establishments, whence actually the threat to their survival decreased. In the late 1700s, it was proved that education and training was possible and during the 19th century, there were schools established for the first time for people with disabilities. These trends towards segregated education soar to peak in size and numbers during the 20th century. Remedial education, special education and integration have had their time in the field and current era is propelled by the term ‘Inclusion’. The definitions of inclusive education are abound. There is no universally accepted definition for ‘Inclusion’. It is shaped by the heterogeneity of inclusive ideas subsumed by history and local cultural perspectives. These ideas and practices across countries sometimes converge and at other times remain isolated. Models of Services The various initiatives for disabled always reflected two primary approaches to rehabilitation i.e., individual pathology and social pathology. In the former approach, the individual is seen as problem while in latter the environment is seen as problem. Within these two approaches, four models of disability emerged, which are: The charity model The bio-centric model The functional model The human rights model (NCERT, 2006). The Charity Model The charity model brought out various welfare measures like providing care, shelter and basic needs. This resulted in establishment of more number of residential units that provided custodial care. These institutions functioned like detention centres and there was no public accountability or comprehensive provisions of services that would enhance the quality of life for individuals with disabilities. Eventually, this model resulted in marginalization and disconnect with the larger society. The Bio-centric Model Evolving from the previous model, bio-centric model regards disability as a medical or genetic condition and prompted to seek medical treatments as only means of management. The role of family, society and government was flippant according to this model. However, medical diagnoses and biological treatments have to be necessarily part of the rehabilitation of the disabled along with the family and social support to participate in the activities of social life. The Functional Model In the functional model, entitlement to rights is differentiated according to judgments of individual incapacity and the extent to which a person is perceived as being independent to exercise his/her rights. For example, a child’s right to education is dependent on whether or not the child can access the school and participate in the classroom, rather than the obligation being on the school system becoming accessible to children with disabilities. Thus, it may not pose obligation to schools for facilitating barrier free education. The Human Rights Model The human rights model positions disability as an important dimension of human culture and it affirms that all human beings are born with certain inalienable rights. According to this model, the principle of respect for difference and acceptance of disability as part of human diversity and humanity is important, as disability is a universal feature of the human condition. It purports to identify those barriers for participation in society and removes them. Advocating for non discrimination, it also calls for reasonable differentiation only to create specialized support services for effective participation in the society. The human rights model to disability on the one hand requires that the States play an active role in enhancing the level of access to public freedoms and on the other requires that the enjoyment of rights by persons with disabilities is not hampered by thirdparty actors in the private sphere. Educational institutions and industry, both in the public and private sectors, should ensure equitable treatment to persons with disabilities. Phases of Services Three phases are evident when looking at the services provided for individuals with disabilities Era of institutionalization In the first period, era of institutionalization, dependence and segregation were impetus and services were underpinned by medical model. This roughly ended in mid 1970s paving way to era of deinstitutionalization. The locus of services for people with disabilities during this period was out of home. As a result, institutional population and nursing home population soared. The services were limited to medical concerns and primary care. Observed by inadequacies and abuse in institutional care, litigation increased and development for standards of services was articulated. The standards were an effort to assure physical, social and psychological well-being of the persons with disabilities in institutional care. Care standards on staffing ratios, daily schedules, professional qualifications, nutritional content of the meals, physical and personal space of the residents, number of residents etc. were spelled out. Era of deinstitutionalization This period prevailed during 1976 to 1986 and was marked by creation of community services and emphasis on provision of specialized services for individuals with disabilities to learn, grow and participate in the activities of society. During this period, day care programs, individualized programming, outpatient centers and accessible housing were part of the reform. The person with disabilities became an object to be trained, habilitated, socialized, screened, assessed and assisted through a continuum of educational, vocational and residential settings. Small intermediate care facilities, half way housing, group homes etc were alternatives to institutionalization. The guiding force was the assumption that all people regardless of the levels of their abilities or severity of their disabilities could grow and develop. This approach was actively applied to interventions for these individuals to acquire skills. Elaborate teaching regimes, pre-articulated learning objectives and careful monitoring of the progress on individual basis became contingent. The new therapeutic and rehabilitation efforts were developed by a growing cadre of mental health professionals. Era of community membership The third and current period, era of community membership, is steered by functional supports to enhance community integration, independence, quality of life, and individualization. The concept of functional supports focused on adapting the environment and supports to the individual instead of adapting the individual to the environment. The emerging emphasis is removing the stigma of “clienthood” from people with disabilities and moving the support to where people lived, i.e., instead of surrounded by professionals and therapists, let them be surrounded by friends, family and community. Perspectives of Inclusive Education • Clough and Corbett (2000) discussed five perspectives in line with historical development of inclusive ideas and practices. The authors in their work have stated that these perspectives are never wholly exclusive of each other nor do they have linear development of ideas. In the course of time, ideas and practices became either overriding to each other or remained exclusive. The Psycho-medical legacy • This is understood as the system of broadly medicalized ideas which essentially saw the individual as being somehow ‘in deficit’ and in turn assumed a need for a ‘special’ education for those individuals. Clinic based assessments were provided by doctors, or psychiatrists mainly to determine if the child needs to be placed in “special education” in a segregated setting. The sociological response • This position broadly represents the critique of the “psycho-medical legacy”, and draws attention to a social construction of special educational needs. It clearly focused on social disadvantage rather than individual deficit. Barton (in interview, 1988) said it is about removal of all forms of oppression. Curricular approaches • Such approaches emphasize the role of the curriculum in both meeting and for some writers, effectively creating - learning difficulties. The above two perspectives however powerful they might be, offered no practical solutions to the teachers in the classrooms. At the same time, a related development of curriculum and teaching approaches, which helped to foster a more inclusive school sprang. It articulated on broad range of interventions delivered through the curriculum. School Improvement Strategies • This movement emphasizes the importance of systemic organization in pursuit of truly comprehensive schooling. Hopkins, West and Ainscow (1996) in their work on “Improving the quality of education for all” developed a notion of ‘school effectiveness’ as a movement. • This approach focused on the role of pedagogy in creating inclusion. Stenhouse (1975) stated that curriculum development involves bringing practice in classrooms and teaching plans closer together through an evaluation by teachers using their own curricula Disability studies critique • These perspectives often from ‘outside’ education elaborate an overtly political response to the exclusionary effects of the psycho-medical model. Disability studies is as much an discipline as educational studies and made unique contributions to debates on inclusive education. It concerns specific issues like social inclusion, inclusion in employment and housing, and educational inclusion in larger contexts. Oliver (1990) has brought out interrelationships between educational and social policy PRINCIPLES OF INCLUSIVE EDUCATION • The education of students with disabilities is based on a number of beliefs and principles. These beliefs and principles guide the policies and services provided for persons with disabilities. • The four key elements of inclusion presented by UNESCO (2005) provide a useful summary of the principles that support inclusive practice. 4 Key Elements • 1. Inclusion is a process. It has to be seen as a neverending search to find better ways of responding to diversity. It is about learning how to live with difference and learning how to learn from difference. Differences come to be seen more positively as a stimulus for fostering learning amongst children and adults. • 2. Inclusion is concerned with the identification and removal of barriers. It involves collecting, collating and evaluating information from a wide variety of sources in order to plan for improvements in policy and practice. It is about using evidence of various kinds to stimulate creativity and problem - solving. • 3. Inclusion is about the presence, participation and achievement of all students. ‘Presence’ is concerned with where children are educated and how reliably and punctually they attend; ‘participation’ relates to the quality of their experiences and must incorporate the views of learners and ‘achievement’ is about the outcomes of learning across the curriculum, not just test and exam results. • 4. Inclusion invokes a particular emphasis on those groups of learners who may be at risk of marginalization, exclusion or underachievement. This indicates the moral responsibility to ensure that those ‘at risk’ are carefully monitored, and that steps are taken to ensure their presence, participation and achievement. Seven inter - connected areas of key principles are put forward by European Agency for Development in Special Needs Education (2009). INCLUSIVE EDUCATIONPOLICY • Prior to 1944, the educational provisions were made based on the type of disabilities and were predominantly welfare measures. It focused more on livelihood training rather than education. However “inclusive education” gained momentum in developed countries like USA, UK and Canada with policy initiatives and researches to promote education. Increased awareness and advocacy among parents on the educational needs of their children also exerted pressure to improve educational provisions (Dash, 2006). An overview of the legal frameworks related to inclusive education from 1948 to 2007 2007 United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples 2006 Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities 2005 Convention on the Protection and Promotion of Diversity in Cultural Expressions 1999 Convention concerning the Prohibition and Immediate Action for the Elimination of the Worst Forms of Child Labour 1990 Convention on the Rights of the Child 1989 Convention concerning Indigenous and Tribal People in Independent Countries 1979 Convention on the Elimination of All forms of Discrimination Against Women 1965 International Convention on the Elimination of All forms of Racial Discrimination 1960 Convention against Discrimination in Education 1948 Universal Declaration of Human Rights Inclusive education means all learners, young people—with or without disabilities being able to learn together in ordinary preschool provisions, schools, and community educational settings with appropriate network of support services. Inclusion is seen as a process of addressing and responding to the diversity of needs of all children, youth and adults through increasing participation in learning, cultures and communities and reducing and eliminating exclusion within and from education. It involves changes and modifications in content, approaches, structures and strategies with a common vision that covers all children of the appropriate age range and a conviction that it is the responsibility of the regular system to educate all children (UNESCO, 2009). PROGRAMMES IN INCLUSIVE EDUCATION • Over the years, although government programmes such as Operation Blackboard8 and Lok Jumbish9 focused mainly on infrastructure, girls, scheduled • Operation Blackboard was launched in 1987 to improve the school environment. It aimed to enhance the retention and learning achievement of children by providing essential facilities in all primary schools. • Lok Jumbish is to promote community mobilization and participation thereby ensuring that village community takes responsibility for providing quality education for every child in their efforts to universalize primary education and improve quality. caste and scheduled tribe children, others had or have inclusive education. Components which ensure the visibility of children with disabilities. Janshala This community schools programme started in 1998 and now replaced by SSA, was a collaboration between the Government of India and the UNDP, UNICEF, UNESCO, the ILO, UNFPA and supported the government drive towards universal primary education. It covered 120, mainly rural blocks in 9 States where there is evidence of low female literacy, child labour and SC / ST children not catered for under DPEP (Mukhopadhyay, 2005).Unfortunately, due to limited availability of data, it is not possible to elaborate on any issues arising on the Janshala programme, which has a component designed to improve the attendance of difficult to reach groups of children including children with disabilities. Sarva Shiksha Abhiyan (SSA) Sarva Shiksha Abhiyan (SSA) is the government’s millennial “Education for All” umbrella program for all education schemes, which aims to universalize elementary education. The goals are that all children aged 6 - 14 - i) will be in some form of education by 2003, ii) will complete 5 years’ primary education by 2007 and iii) will complete 8 years’ education by 2010 (GOI, 2002b). Non Governmental Organizations There are many international, national, and local NGOs involved with disability issues in India. Many local NGOs, while diverse and widespread tend to be based on a charity / welfare approach (Thomas, 2004) and informed by the medical model. Although the exact number is unknown, there are at least 1,000 NGOs and voluntary organizations actively engaged in education of which the government funded 701 with grants in aid in 2004-2005 Private schools • The explosive growth of private schools in recent years in India, in both urban and rural areas is seen by many to be a result of dissatisfaction with the poor quality education provision in government schools (Nambissan, 2003; Singal & Rouse, 2003). However, the private schools which have been voluntarily implementing inclusive education are mostly found in urban areas demonstrating the geographical inequalities so prevalent in the Indian context. In addition, as these private schools require the payment of fees, this inclusive education is not accessible to all and so somewhat exclusive, although some admit ‘bright’ children from deprived backgrounds as a charitable gesture DEPARTMENT OF EDUCATION (DoE) PHILOSOPHY OF INCLUSION FOR STUDENTS WITH DISABILITY DoE values professionalism, respect, innovation, diversity and excellence. Through quality strategies, programs, people, partnerships and systems, the Department of Education is focused on Growing Success Together for all Territorials. We believe that inclusivity embraces the idea that everyone is an individual and their diversity is respected. Inclusion starts from a recognition of the differences between students and works to minimize barriers in education for all students. Inclusion in education means: Valuing all students Recognizing that inclusion in education is one aspect of an inclusive society • Increasing the participation of students in, and reducing their exclusion from, the culture, curricula and communities of schools Restructuring the culture, policies and practices in schools so that they respond to the diversity of students. Inclusion involves adjusting curriculum, assessment practices, teaching styles and the physical environment to provide for the needs of all students. Act and the Northern Territory AntiDiscrimination Act 2014. Policies and resources to support the inclusion of students include: PowerPoint presentations Parent brochure Factsheets A set of support guidelines The Whole School Approach to Improving Student Learning Principals, as leaders of the school, are accountable for student performance and achieving the school’s improvement goals and performance targets through effective, quality education services. In aligning the Students with Disability Policy implementation with the Accountability and Performance Improvement Framework (APIF), principals can: Build the capacity of the school Be accountable for the learning outcomes and wellbeing of students Ensure that all school staff meet expected standards of service provision Ensure the school complies with relevant legislation, regulations and organizational standards including the management of finances, assets and other resource Philosophy of inclusion – problems and challenges Dr. Pallvi Pandit The right of every child to education is proclaimed in The Universal Declaration of Human Right; besides, education is also a fundamental human right. The Universal Declaration of Human Rights and the Convention on the Rights of the Children all stipulate that the right of everyone to education is the responsibility of the whole world. As is well known the most difficult point in universalizing the compulsory education lies in education for the disabled, especially in povertystricken areas. 'Including the Excluded' - "Inclusion is about the intentional building of relationships where difference is welcomed and all benefit." Inclusion is not a new concept in education. Related terms with a longer history include mainstreaming, integration, normalization, least restrictive environment, deinstitutionalization, and regular education initiative. Some use several of these terms interchangeably; others make distinctions Problems or Barriers with Inclusion in the Classroom Despite the principles of inclusion underlying legislation and policy and its inherent presence in the documents research suggests that inclusion in actual practice varies widely from service to service. Children with special needs are often seen as requiring special education separate to the mainstream. This limits their attendance and full participation in the regular life of the service. Separation gives rise to a number of barriers to inclusion, including hostility from other children’s parents, resourcing issues, and a lack of knowledge about how to include children with special needs. The following are some of the external barriers Attitudinal barriers It has been noted that disabled students suffer from physical bullying, or emotional bullying. These negative attitudes results in social discrimination and thus leads to isolation, which produces barriers to inclusion. Regarding disabled children some regions still maintain established beliefs that educating the disabled is pointless. It is sad to note here that these barriers are caused by society, which is more serious to any particular medical impairment. Physical barriers: Along with the attitudinal barriers which are faced by the learners on the daily basis, another important barrier is the physical barriers, which includes school buildings, playgrounds, washrooms, library etc. Apart from this, the majority of schools are physically inaccessible to many learners because of poor buildings, particularly rural areas. Inappropriate Curriculum as a barriers: In any education system, the curriculum is one of the major obstacles or tools to facilitate the development of more inclusive system. Curriculum includes the broad aims of education and has its implications on transactional and evaluation strategies. In our country of diversity, curriculum is designed centrally, hence which leaves little flexibility for local adaptations or for teachers to experiment and try out new approaches Untrained Teachers as barriers: For implementing the inclusive education successfully, it is important that teachers must have positive attitudes towards learners with special needs. But, because of lack of knowledge, education, understanding, or effort the teachers give inappropriate substitute work to the learners, which eventually leads to learners dissatisfaction and poor quality of learning. Organization of the Education System: In our country, there are different types of schools such as private, government; public schools are developing inequality by offering differential levels of facilities and support. Those having an access to private schools have higher possibility of success as compared to those who go to government schools. Therefore, it is important like many developed countries, the common school system policy must be place properly. Funding System: Quite a number of factors can be interpreted as barriers for inclusion. In some countries the funding system is not enhancing inclusive practices (Meijer, 1999). Not only the funding system may inhibit inclusion processes; but also the existence of a large segregated setting itself is a hindrance for inclusion. Problem for Classroom Teachers: A classroom teacher is expected to select educational methodology to best suit each student. This is a challenging goal for one teacher who potentially has more than 30 students in each of five to seven classes. Most students can be grouped with other students whose educational needs are similar. This may reduce the planning required to two or three groups. If you add special needs students who have severe learning delays, developmental issues, or who speak little or no English, this task can feel almost insurmountable – especially if the inclusive classroom does not include a co-teacher Problem for Special Education Teachers: The biggest problem for special education teachers who have students in inclusive classrooms is being available to every student. For example, if a particular subject teacher has 50 students who are distributed through 15 classes during any given period there is no way to assist every student every day. Students may have to be pulled out of class a few times a week for additional services, which also impacts the ability of the child and classroom teacher to maintain pace Problems for Students: Special education and mainstream students both benefit from being in a classroom together. After all, work and life are not segregated by intelligence or ability. However, there are still some problems that need to be recognized. In a classroom of 30, with one or two special education students, it can be difficult for the classroom teacher to give the individual time and attention the students require and deserve. If the teacher is focusing on the special needs students, the students who need a more challenging Parents of other Children: Research indicates that some parents of children who attend services where there are children with special needs enrolled held the view that “if children with disabilities were deemed to be too different, too difficult or too disabled to teach, or their participation in centres was seen as interfering with the learning of other children, and as taking up time, money or attention from the deserving ‘normal’ children, then their enrolment, attendance and participation in early childhood education should be questioned.” Such attitudes can present a very significant deterrent to children with special needs and their families’ sense of belonging and acceptance. "Inclusive education is concerned with removing all barriers to learning, and with the participation of all learners vulnerable to exclusion and marginalization. It is a strategic approach designed to facilitate learning success for all children. It addresses the common goals of decreasing and overcoming all exclusion from the human right to education, at least at the elementary level, and enhancing access, participation and learning success in quality basic education for all." – Susie Miles “Together We Learn Better: Inclusive Schools Benefit All Children”.