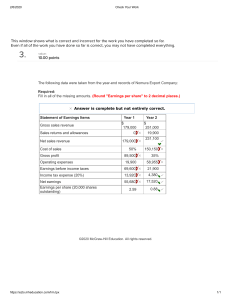

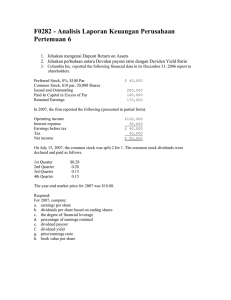

Earnings Announcement Disclosures and Changes in Analysts’ Information* ORIE E. BARRON, Pennsylvania State University DONAL BYARD, Baruch College – CUNY YONG YU, University of Texas at Austin ABSTRACT This study examines how financial disclosures with earnings announcements affect sell-side analysts’ information about future earnings, focusing on disclosures of financial statements and management earnings forecasts. We find that disclosures of balance sheets and segment data are associated with an increase in the degree to which analysts’ forecasts of upcoming quarterly earnings are based on private information. Further analyses show that balance sheet disclosures are associated with an increase in the precision of both analysts’ common and private information, segment disclosures are associated with an increase in analysts’ private information, and management earnings forecast disclosures are associated with an increase in analysts’ common information. These results are consistent with analysts processing balance sheet and segment disclosures into new private information regarding nearterm earnings. Additional analysis of conference calls shows that balance sheet, segment, and management earnings forecast disclosures are all associated with more discussion related to these items in the questions-and-answers section of conference calls, consistent with analysts playing an information interpretation role with respect to these disclosures. Information livree dans les communiques sur les resultats et modification de l’information produite par les analystes RESUM E Les auteurs se demandent comment l’information financiere livree dans les communiques sur les resultats influe sur l’information produite par les analystes de maisons de courtage en ce qui a trait aux resultats futurs, en s’interessant plus particulierement aux renseignements contenus dans les etats financiers et les previsions de resultats de la direction. Les auteurs constatent que les renseignements que contiennent les bilans et les donnees sectorielles sont associes a une augmentation de la mesure dans laquelle les previsions des analystes quant aux resultats trimestriels a venir s’appuient sur de l’information privilegiee. * Accepted by Sudipta Basu. We thank the editor for many helpful suggestions and comments. We also thank two anonymous reviewers, Linda Bamber, Anna Brown, Masako Darrough, Andy Leone, Melissa Lewis, Edward Li, Pat O’Brien, Min Shen, Jim Vincent, Eric Wang, Ryan Wynne, Chris Yust, and conference participants at the AAA Annual Meetings, the Accounting and Financial Economics conference at the University of Texas – Austin, and seminar participants at Baruch College – CUNY, the University of Queensland, and the University of Technology, Sydney. We are grateful to Irfan Ahmed, Monil Doshi, Xiaoge Fan, Hao Li, Ruodan Lin, Shijian Liu, Hanna Rosen, Zhiyuan Tu, Ritesh Veera, and Eric Wang for their help in collecting the data. In addition, we acknowledge the contribution of 10-K Wizard for providing 8-K transcripts, CallStreet for providing conference call transcripts, and I/B/E/S International Inc. for providing earnings per share forecast data. Donal Byard gratefully acknowledges the financial support provided by a Lang Fellowship from Baruch College, and a PSC-CUNY grant from the City University of New York (PSC-CUNY # 69729-00 38). Contemporary Accounting Research Vol. 34 No. 1 (Spring 2017) pp. 343–373 © CAAA doi:10.1111/1911-3846.12275 344 Contemporary Accounting Research Des analyses plus poussees revelent que les renseignements contenus dans les bilans sont associes a une augmentation de la precision de l’information tant commune et que privilegiee dont disposent les analystes, que les renseignements sectoriels sont associes a une augmentation de l’information privilegiee dont disposent les analystes, et que l’information relative aux previsions de resultats de la direction est associee a une augmentation de l’information commune dont disposent les analystes. Ces resultats confirment que les analystes transforment l’information contenue dans les bilans et l’information sectorielle en nouvelle information privilegiee relative aux resultats a court terme. Une analyse supplementaire des conferences telephoniques revele que l’information contenue dans les bilans, l’information sectorielle et les previsions de resultats de la direction sont toutes associees a de plus amples discussions de ces elements dans la portion des conferences telephoniques consacree aux questions et reponses, ce qui confirme que les analystes jouent un r^ ole d’interpretation de l’information relativement a ces informations. 1. Introduction This study examines how financial disclosures with firms’ quarterly earnings announcements affect financial analysts’ information about future earnings. It is common practice now for firms to include various financial disclosures in addition to “bottom line” earnings information in their earnings announcement press releases (see Chen, DeFond, and Park 2002; Francis, Schipper, and Vincent 2002). However, to date there is little evidence as to whether and how these financial disclosures are useful to sell-side analysts. We fill this gap by examining how disclosures of financial statements and management earnings forecasts, the most common types of financial disclosures included in firms’ earnings announcements, affect financial analysts’ information about upcoming earnings, as reflected in their quarterly earnings forecasts. Analysts discover new information that preempts subsequent public disclosures, and interpret and process public disclosures into new insights (Chen, Cheng, and Lo 2010). We expect the information interpretation role to dominate for financial statement disclosures. Financial statements are complex, disaggregated disclosures, and analysts apply their knowledge and skills to process the data contained in these statements into forecasts of future earnings. Because analysts vary in their backgrounds, knowledge, and skills, the insight analysts extract from their interpretations of a financial statement disclosure are also likely to differ. Hence, financial statement disclosures are likely to facilitate more private information regarding future earnings, causing analysts’ earnings forecasts to be based relatively more on private information. In contrast, we expect analysts’ information discovery role before an earnings announcement to dominate the effect of management earnings forecasts on analysts’ information at the time of the announcement. Unlike financial statements, management earnings forecasts are a relatively simple form of disclosure requiring less processing by analysts forecasting future earnings, and are thus more likely to be commonly interpreted by analysts. As a result, management earnings forecasts are more likely to substitute for analysts’ private information discovered before the announcement, causing analysts’ earnings forecasts after earnings announcements to be based relatively more on common information. We hand-collect data on disclosures of financial statements and management earnings forecasts for a sample of 1,445 quarterly earnings announcements from 2003 to 2004. We use the analyst consensus measure developed by Barron, Kim, Lim, and Stevens (1998, hereafter BKLS) to gauge the degree to which analysts’ forecasts are based on common vs. private information. If, when forecasting earnings, analysts primarily play an information interpretation (discovery) role with respect to a disclosure, then we expect the disclosure to trigger more private (common) information, resulting in a decrease (increase) in analyst consensus regarding future earnings. CAR Vol. 34 No. 1 (Spring 2017) Disclosures and Analysts’ Information 345 We find that balance sheet and segment disclosures are associated with a decrease in analyst consensus about upcoming quarterly earnings, indicating that analysts’ quarterly earnings forecasts incorporate relatively more private information after these disclosures are released.1 Further, we find that balance sheet disclosures are associated with an increase in the precision of both analysts’ common and private information, segment disclosures are associated with an increase in analysts’ private information, and management earnings forecast disclosures are associated with an increase in analysts’ common information. We also find that both balance sheet and segment disclosures are associated with an increase in the accuracy of analysts’ average forecasts. Overall, these results are consistent with analysts processing balance sheet and segment disclosures into new insights regarding near-term earnings and analysts primarily playing an information interpretation role with respect to balance sheet and segment disclosures. To provide more general evidence on analysts’ information interpretation role, we examine the relation between the same financial disclosures and the content of the questions-and-answers (Q&A) section of conference calls. Since each analyst is typically only allowed to ask a limited number of questions in a conference call, we expect analysts to ask questions about important inputs to their various forecasting and valuation models. If a disclosure provides useful inputs for any of analysts’ models and analysts focus on interpreting the disclosure, then we expect the disclosure to trigger more analysts questioning management about the content of that disclosure in the conference call Q&A. Because analysts can ask questions to extract information they need for any of their forecasting and valuation tasks (rather than just forecasting next quarter’s earnings), this analysis sheds light on analysts’ information interpretation role more generally. We find that balance sheet, segment, and management earnings forecast disclosures are all associated with more discussion related to these items in the conference call Q&A, consistent with these disclosures generally providing useful inputs for analysts’ research and analysts playing an information interpretation role with respect to these disclosures. Our results are robust to using alternative disclosure measures that consider disclosure quality, controlling for other qualitative disclosures that firms may also include in their earnings announcements, and controlling for the tone of language used in press releases. Our results are also robust to controlling for firm characteristics associated with firms’ disclosure policies, and correcting for the endogeneity of firms’ disclosure choices using a two-step Heckman model. Our study contributes to our understanding of the relation between financial disclosures and analysts’ informational roles by showing that balance sheet and segment disclosures enhance the information interpretation role of analysts and help analysts produce new private information about upcoming quarterly earnings. Our study also adds to research examining the usefulness of the financial disclosures firms increasingly include in their earnings announcements. The rest of the paper is organized as follows. Section 2 reviews related research and develops our hypotheses. Section 3 describes our data and design. Sections 4–6 report our main tests, additional analyses, and robustness checks, respectively. Section 7 concludes. 2. Related research and hypothesis development Related research Prior research examining the informational roles of financial analysts has largely focused on the relation between firms’ aggregate disclosures and analysts’ information, and does not differentiate among different types of disclosures. Using different settings and different 1. We do not examine income statement disclosures because all of the earnings announcements in our sample contain an income statement. CAR Vol. 34 No. 1 (Spring 2017) 346 Contemporary Accounting Research methodologies, these studies provide evidence consistent with analysts fulfilling both an information discovery role and an information interpretation role. On the one hand, consistent with an information discovery role, some studies find a negative relation between the information content of financial disclosures and that of analyst research. For example, Shores (1990) finds that market reactions to earnings announcements are smaller for firms with larger analyst following, consistent with analysts’ reports preempting earnings announcement disclosures.2 Ayers and Freeman (2003) report that current stock returns are more strongly associated with future earnings for firms with higher analyst following, suggesting that analysts’ reports preempt the information contained in firms’ future earnings. Studies examining analysts’ activities for high-intangible firms also show that analysts exert more effort and provide more informative reports for high-intangible firms, which tend to have poorer-quality financial disclosures (Barth, Kasznik, and McNichols 2001; Barron, Byard, Kyle, and Riedl 2002). On the other hand, supporting the information interpretation role, other studies find a positive relation between the information content of financial disclosures and that of analysts’ research. For example, Lang and Lundholm (1996) find that firms with higherquality disclosures tend to attract more analyst following. Barron, Byard, and Kim (2002) find a decrease in analyst consensus around earnings announcements, consistent with earnings announcements on average triggering private information production by analysts. Both Francis, Schipper, and Vincent (2002) and Frankel, Kothari, and Weber (2006) find a positive association between the absolute abnormal returns associated with analyst reports and the absolute abnormal returns associated with earnings announcements, suggesting that more informative earnings announcements enhance the information content of analysts’ reports.3 In a recent study, Chen et al. (2010) show that a different informational role dominates depending on the timing of analysts’ reports with respect to firms’ earnings announcements. They find a negative (positive) relation between the information content of earnings announcements and that of analysts’ reports issued in the week prior (subsequent) to earnings announcements, indicating that the information discovery (interpretation) role dominates in the period before (after) earnings announcements. They also examine all weeks around earnings announcements and report an overall negative relation between the information content of earnings announcements and that of analyst reports. They show that the overall positive relation reported in Francis et al. (2002) could be attributable to the research design employed. While prior studies have largely focused on the aggregate relation between firms’ overall disclosures and analysts’ information, a notable exception is prior work that examines changes in analysts’ information around a regulatory change in segment reporting (i.e., the adoption of Statement of Financial Accounting Standard (SFAS) 131). Berger and Hann (2003) find that analysts have access to some of the new segment information before it was made public by the adoption of SFAS 131. Botosan and Stanford (2005) show that, after the adoption of SFAS 131, analysts tend to rely relatively more on common information when forecasting future earnings. These results are consistent with the disclosure of additional segment information under SFAS 131 replacing private information acquired by analysts prior to the rule change. 2. 3. Bhushan (1994) finds no relation between analyst following and the magnitude of the post-earningsannouncement drift after controlling for share price and trading volume. But Zhang (2008) finds a negative relation between analyst responsiveness and the post-earnings-announcement drift. Altinkilicß and Hansen (2009) find that confounding news events can introduce noise into daily return-based measures of the information contents of analysts’ stock recommendations (see also Li, Ramesh, Shen, and Wu 2015). CAR Vol. 34 No. 1 (Spring 2017) Disclosures and Analysts’ Information 347 Hypothesis development Theoretical models of information acquisition and processing can help illustrate analysts’ two informational roles. Consistent with the information discovery role, theory suggests that a public disclosure can decrease private information that analysts acquire before the disclosure (e.g., Kim and Verrecchia 1991; Demski and Feltham 1994). In such a model, a public disclosure serves to provide common information that substitutes for the private information acquired before the disclosure, thereby increasing common information and reducing private information. On the other hand, consistent with the information interpretation role, a public disclosure can also trigger private information production (e.g., Indjejikian 1991; Kim and Verrecchia 1994; Harris and Raviv 1993). These models stress the role of unique knowledge and skills in interpreting and processing public disclosures. For example, an analyst with accounting expertise can better understand the impact of changes in accounting methods on future earnings, while an analyst with a background in international trade can better predict the impact of growth in emerging markets on future earnings. When analysts apply their heterogeneous knowledge and skills to process the same disclosure, they are likely to obtain unique interpretations and insights. We posit that, when forecasting future earnings, analysts’ information interpretation role is likely to dominate for disclosures of financial statements. Financial statement disclosures convey useful information regarding future earnings. For example, fundamental analysis research provides evidence consistent with balance sheet components predicting future earnings and returns (e.g., Ou and Penman 1989a,b; Lev and Thiagarajan 1993; Abarbanell and Bushee 1997, 1998; Piotroski 2000). However, financial statement components are also complex, disaggregated financial disclosures. In order to transform the useful information contained in financial statements into specific forecasts of future earnings, analysts need to process these disclosures using their own (unique) knowledge and skills. Because analysts have heterogeneous backgrounds, knowledge, and skills, the information (about future earnings) that each analyst is able to extract from the same financial statement is likely to differ, causing analysts’ earnings forecasts to contain relatively more private information after such disclosures.4 Thus, we expect financial statement disclosures to be associated with a decrease in the degree to which analysts base their earnings forecasts on common information. Our first hypothesis, stated in the alternative form, is: H1. The disclosure of financial statements in earnings announcements is associated with a decrease in the degree to which analysts base their earnings forecasts on common information. We expect analysts’ information discovery role before the announcement to dominate the effect of management earnings forecasts on the change in analysts’ information at the time of the announcement. Compared with financial statements, management earnings forecasts are a relatively straightforward disclosure that directly predicts future earnings. Management earnings forecasts are thus likely to require less processing and interpretation by analysts when they are forecasting future earnings. As a result, analysts are more likely to agree upon the meaning of a management earnings forecast (as it relates to future earnings), such that the common information it conveys serves mainly to substitute for analysts’ predisclosure private information regarding future earnings. Thus, we expect that the disclosure of management earnings forecasts will be associated with an increase in the 4. Alternatively, to the extent that financial statement disclosures serve as common inputs to analysts’ forecasting models and/or analysts focus on searching for common information in response to those disclosures, financial statement disclosures could also cause analysts’ earnings forecasts to rely relatively more on common information. CAR Vol. 34 No. 1 (Spring 2017) 348 Contemporary Accounting Research degree to which analysts base their earnings forecasts on common information.5 Our second hypothesis, stated in the alternative form, is: H2. The disclosure of management earnings forecasts in earnings announcements is associated with an increase in the degree to which analysts base their earnings forecasts on common information. 3. Sample selection and research design Sample selection We hand-collect press releases for a sample of quarterly earnings announcements between March 30, 2003 and September 30, 2004. Our sample period represents a window immediately after new Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) disclosure rules came into effect. Directed by the Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002, the SEC adopted new disclosure rules including the addition of Item 12 to Form 8-K, amendments to Item 10 of Regulation S-K, and the adoption of Regulation G. These new rules require companies―for the first time―to file their earnings announcement press releases with the SEC on Form 8-K and provide more information about any non-GAAP financial information.6 These new rules subjected earnings announcement press releases to SEC oversight for the first time and are thus likely to have altered firms’ reporting incentives with respect to their earnings announcement disclosures. Additionally, these new rules increased the transparency of any non-GAAP financial information included in earnings announcements. Selecting a sample period after these new rules came into effect benefits our study in a number of ways. First, it provides a sample of earnings announcements subject to a consistent regulatory regime. Second, the availability of earnings announcement press releases through 8-K filings significantly reduces costs and errors in data collection. Third, to the extent that the new rules enhance the quality of earnings announcement disclosures (e.g., Kolev, Marquardt, and McVay 2008), we are able to conduct more powerful tests of the effects of these disclosures. We focus our sample period immediately after the enactment of the new rules because the cross-sectional variation in firms’ earnings announcement disclosures is much lower in later periods.7 Specifically, we select a sample of quarterly earnings announcements made between 30 March 2003 and 30 September 2004 that meet the following requirements: • 5. 6. 7. The earnings announcement date for quarter q is available from COMPUSTAT and I/B/E/S. When the two sources disagree, we use the earlier of the two dates (Dellavigna and Pollet 2009); Alternatively, it is also possible that in order to differentiate themselves and stimulate trading, analysts may react to simple disclosures like management earnings forecasts by searching for more private information. Another possibility is that analysts may disagree on how to interpret management earnings forecasts because they differ in how credible they perceive these management earnings forecasts to be (Hutton and Stocken 2009). Regulation G requires companies releasing non-GAAP financial information to provide “a presentation of the most directly comparable GAAP financial measure and a reconciliation of the disclosed non-GAAP financial measure to the most directly comparable GAAP financial measure” (see http://www.sec.gov/rules/ final/33-8176.htm). The over-time increase in the incidence of disclosures made with earnings announcements significantly reduces the cross-sectional variation in firms’ disclosures in later periods. For example, for our 2003–2004 sample period, we find that 86 percent of the earnings announcements in our sample include a balance sheet. Using the same sample-selection criteria but a sample period confined to the first fiscal quarter of 2008, we find that 98 percent of the earnings announcements in this later sample period contain a balance sheet disclosure (untabulated). CAR Vol. 34 No. 1 (Spring 2017) Disclosures and Analysts’ Information • • • • • 349 Data to calculate market capitalization and the book-to-market ratio at the end of quarter q are available from COMPUSTAT; Data are available from the I/B/E/S unadjusted detail file for at least three individual analysts who issue a forecast of quarter q+1 earnings in the 45-day period before the quarter q earnings announcement date, and who also revise these forecasts in the period between the quarter q earnings announcement and the 10-K/Q filing date.8 Matching individual analysts before and after the quarter q earnings announcement date ensures that we compute the change in BKLS consensus using forecasts from the same set of individual analysts. We use I/B/E/S unadjusted data to avoid potential measurement errors resulting from rounding (see Payne and Thomas 2003); Actual earnings per share for quarter q+1 are available from the I/B/E/S unadjusted database; Data are available to calculate the surprise in quarter q earnings: at least one forecast of quarter q earnings is available from the 45-day period immediately before the quarter q earnings announcement date, and actual earnings per share for quarter q are available from the I/B/E/S unadjusted detail file; and A copy of the 8-K earnings announcement press release for quarter q is available from the 10-K Wizard database. We use the 8-Ks to hand-collect data for the disclosure of financial statements (i.e., an income statement, a balance sheet, a statement of cash flows, and segment data) and management earnings forecasts in the earnings press release. Our final sample consists of 1,445 quarterly earnings announcements. Study design To test our hypotheses, we estimate the following regression model: Dqiq ¼ u0 þ u1 BSiq þ u2 SCFiq þ u3 SEGiq þ u4 MEFiq þ CONTROLSiq þ eiq ; ð1Þ where Dqiq is the change in analyst consensus around the quarter q earnings announcement for firm i. Following prior research (e.g., Barron et al. 2002; Barron, Byard, and Yu 2008; Botosan and Stanford 2005; Byard, Li, and Yu 2011), we estimate analyst consensus using the BKLS model. BKLS show that consensus (q) can be expressed in terms of the variance of forecasts (D), the squared error in the mean forecast (SE), and the number of SED=N forecasts (N) as follows q ¼ ð11=N ÞDþSE specifically, using matched individual forecasts of quarter q+1 earnings made before and after the quarter q earnings announcement, we estimate analyst consensus (q) both before and after the quarter q earnings announcement for firm i and then calculate the change in consensus (Δqiq). Consensus (q) captures the degree to which analysts’ forecasts are based on common information, that is, the ratio of common-to-total information in analysts’ forecasts. In other words, consensus (q) is equal to one minus the proportion of private information in analysts’ forecasts. The change in consensus (Δq) thus measures the change in the degree to which analysts’ earnings forecasts are based on common information. One caveat of this consensus measure is that the BKLS model assumes that any difference between analysts’ forecasts reflects analysts’ private information and not noise. As a result, in section 4 below, we examine the robustness of our inferences to using a non-BKLS measure (i.e., analysts’ forecast accuracy). 8. If the 10-K/Q is filed more than 30 days after the earnings announcement date, the post-announcement period is capped at 30 days. This ensures that earnings forecasts issued in the post-announcement window reflect the earnings announcement disclosures. Prior research shows that analysts’ forecast revisions tend to be concentrated in the days immediately after earnings announcements (e.g., Stickel 1989; Ivkovic and Jegadeesh 2004). CAR Vol. 34 No. 1 (Spring 2017) 350 Contemporary Accounting Research Our explanatory variables are as follows. BSiq is an indicator variable equal to one if the earnings announcement press release for firm i in quarter q contains a balance sheet, and zero otherwise. SCFiq is an indicator variable equal to one if the earnings announcement press release for firm i in quarter q contains a statement of cash flows, and zero otherwise. SEGiq is an indicator variable equal to one if the earnings announcement press release for firm i in quarter q contains segment data, and zero otherwise.9 MEFiq is an indicator variable equal to one if the earnings announcement press release for firm i in quarter q contains a management earnings forecast, and zero otherwise. H1 predicts that the disclosure of balance sheets, cash flow statements, and segment data will all be associated with a decrease in the degree to which analysts’ forecasts are based on common information, that is, a decrease in consensus, so we expect that: u1, u2 and u3 < 0. H2 predicts that management earnings forecasts will be associated with an increase in the degree to which analysts’ forecasts are based on common information, that is, an increase in consensus, so we expect that: u4 > 0. CONTROLSiq refer to a number of control variables we include in equation (1) to capture earnings announcement and firm characteristics that are likely to affect the change in analyst consensus. Specifically, we define the quarter q earnings surprise (SURP) as the actual quarter q earnings minus the mean forecast of quarter q earnings issued in the 45day period immediately before the quarter q earnings announcement, scaled by stock price at the end of quarter q. We control for the absolute size of SURP (|SURP|). We also include an indicator variable to control for the sign of the earnings surprises: SIGN is equal to one if SURP is negative, and zero otherwise. Barron et al. (2008) find that analyst consensus decreases more around earnings announcements that report a larger absolute earnings surprise (|SURP|) or a negative earnings surprise (SIGN). We also control for firm size (SIZE), defined as market capitalization at the end of quarter q, since there is likely more demand for analysis of larger firms (Bhushan 1989). Additionally, we include the book-to-market ratio (BM) measured at the end of quarter q to control for the effect that analysts’ forecasts may contain relatively more private information for firms with earnings that are more difficult to forecast (Barth et al. 2001). Finally, we control for calendar quarter fixed effects. 4. Main results Descriptive statistics and correlations Table 1 reports descriptive statistics (panel A) and correlations (panel B) for our sample of 1,445 quarterly earnings announcements. Panel A shows that our sample is composed of relatively large firms: mean (median) market capitalization (SIZE) is $14.4 billion ($3.6 billion). This is not surprising given our requirement that at least three analysts issue forecasts both before and after each earnings announcement. However, this likely reduces the power of our tests since earnings announcements for larger firms tend to be less informative (e.g., Freeman 1987; Collins, Kothari, and Rayburn 1987). Our sample firms have a mean (median) book-to-market ratio (BM) of 0.436 (0.409). The earnings surprise is negative for 27.5 percent of the earnings announcements in our sample (see SIGN, an indicator variable equal to one when an earnings surprise is negative); the mean (median) value of |SURP|, the absolute price-scaled earnings surprise, is 0.003 (0.001). Consistent with Barron et al. (2002), we find that on average there is a decrease in consensus around earnings announcements―the mean (median) change in analyst consensus (Δq) is: 0.006 (0.001). The mean of BS (0.86) indicates that 86 percent of the earnings announcements in our sample include a 9. Our sample includes 156 earnings announcement by single segment firms. We verify that our inferences are unaffected if we drop these observations from our sample. CAR Vol. 34 No. 1 (Spring 2017) TABLE 1 Descriptive statistics and correlations Panel A: Descriptive statistics Variable Mean 25th percentile Median 75th percentile 0.442 2.603 13.210 0.008 0.182 0.262 0.564 0.002 0.001 0.626 1.021 0.001 0.196 2.609 7.539 0.000 0.348 0.500 0.472 0.499 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 1.000 1.000 0.000 1.000 1.000 1.000 1.000 1.000 0.016 0.447 34.877 0.383 0.000 0.000 1.321 0.259 0.001 0.000 3.558 0.409 0.002 1.000 11.071 0.584 Δq ΔCOMMON ΔPRIVATE Δq ΔCOMMON ΔPRIVATE ΔABSMFE BS SCF SEG MEF |SURP| SIGN SIZE BM 1.000 0.315 (<0.001) 1.000 0.767 (<0.001) 0.080 (0.003) 1.000 0.592 (<0.001) 0.179 (<0.001) 0.688 (<0.001) 0.027 (0.299) 0.057 (0.044) 0.084 (0.002) 0.010 (0.697) 0.006 (0.819) 0.010 (0.705) 0.044 (0.094) 0.021 (0.433) 0.051 (0.038) 0.008 (0.759) 0.034 (0.211) 0.006 (0.834) 0.075 (0.075) 0.037 (0.083) 0.056 (0.037) 0.033 (0.210) 0.002 (0.932) 0.041 (0.128) 0.026 (0.317) 0.046 (0.084) 0.021 (0.439) 0.021 (0.415) 0.027 (0.312) 0.001 (0.963) 0.146 (<0.001) 0.291 (<0.001) 0.005 (0.845) (The table is continued on the next page.) 351 CAR Vol. 34 No. 1 (Spring 2017) Panel B: Spearman correlations (above the diagonal) and Pearson correlations (below the diagonal) Disclosures and Analysts’ Information Dependent variables Δq 0.006 ΔCOMMON 1.596 ΔPRIVATE 7.334 ΔABSMFE 0.002 Earnings announcement financial disclosures BS 0.860 SCF 0.504 SEG 0.334 MEF 0.536 Control variables |SURP| 0.003 SIGN 0.275 SIZE ($billion) 14.354 BM 0.436 SE CAR Vol. 34 No. 1 (Spring 2017) 0.189 (<0.001) 0.039 (0.110) 0.020 (0.445) 0.027 (0.310) 0.004 (0.894) 0.034 (0.139) 0.044 (0.095) 0.014 (0.587) 0.019 (0.472) 0.004 (0.894) 0.025 (0.341) 0.025 (0.344) 0.046 (0.078) 0.013 (0.623) 0.032 (0.223) 0.024 (0.358) 0.014 (0.456) 0.025 (0.147) ΔCOMMON 0.108 (<0.001) 0.034 (0.202) 0.015 (0.349) 0.042 (0.112) 0.011 (0.851) 0.005 (0.852) 0.017 (0.499) 0.075 (0.004) 0.033 (0.206) ΔPRIVATE 0.043 (0.080) 0.005 (0.839) 0.018 (0.450) 0.016 (0.498) 0.550 (<0.001) 0.117 (<0.001) 0.060 (0.024) 0.028 (0.289) 1.000 ΔABSMFE 0.241 (<0.001) 0.111 (<0.001) 0.059 (0.025) 0.025 (0.438) 0.001 (0.971) 0.172 (<0.001) 0.135 (0.004) 0.125 (<0.001) 1.000 BS 0.105 (<0.001) 0.241 (<0.001) 0.021 (0.434) 0.019 (0.465) 0.024 (0.373) 0.067 (0.011) 0.017 (0.524) 0.241 (<0.001) 1.000 SCF 0.111 (<0.001) 0.001 (0.960) 0.029 (0.274) 0.151 (<0.001) 0.072 (0.006) 0.055 (0.026) 0.111 (<0.001) 0.105 (<0.001) 1.000 SEG 0.023 (0.388) 0.091 (<0.001) 0.004 (0.879) 0.041 (0.119) 0.005 (0.844) 0.059 (0.025) 0.241 (<0.001) 0.111 (<0.001) 1.000 MEF 0.006 (0.678) 0.040 (0.128) 0.021 (0.245) 0.168 (<0.001) 0.040 (0.129) 0.021 (0.419) 0.028 (0.296) 0.095 (<0.001) 1.000 |SURP| 0.047 (0.076) 0.056 (0.031) 0.078 (0.003) 0.001 (0.971) 0.019 (0.465) 0.029 (0.274) 0.091 (<0.001) 0.001 (0.982) 1.000 SIGN 0.094 (<0.001) 0.157 (<0.001) 0.160 (<0.001) 0.090 (<0.001) 0.299 (<0.001) 0.001 (0.981) 0.178 (<0.001) 0.075 (0.004) 1.000 SIZE 0.069 (0.010) 0.140 (<0.001) 0.104 (<0.001) 0.097 (<0.001) 0.044 (0.094) 0.241 (<0.001) 0.094 (<0.001) 0.200 (<0.001) 1.000 BM This table reports descriptive statistics (panel A) and Spearman (above the diagonal) and Pearson (below the diagonal) correlations (panel B) for our sample of 1,445 quarterly earnings announcements. For each earnings announcement q, we require a minimum of three analysts to issue forecasts of quarter q+1 earnings in the 45-day period before the quarter q earnings announcement and also revise the forecasts in the period between the quarter q earnings announcement date and the 10-Q/K filing date. We use these analyst earnings forecasts to calculate our dependent variables (Δq is our main dependent variable). See the Appendix for variable definitions. Two-tailed p-values are reported in parentheses for the Spearman correlations. Notes: BM SIZE SIGN |SURP| MEF SEG SCF BS ΔABSMFE Δq Panel B: Spearman correlations (above the diagonal) and Pearson correlations (below the diagonal) TABLE 1 (continued) 352 Contemporary Accounting Research Disclosures and Analysts’ Information 353 balance sheet. Similarly, 50.4 percent, 33.4 percent, and 53.6 percent of the earnings announcements in our sample include a cash flow statement, segment data, and a management earnings forecast, respectively.10 Panel B of Table 1 reports both Spearman and Pearson correlations. Of the four indicator variables for the financial disclosures we examine, the Spearman correlations show that only SEG is marginally significantly negatively (0.044, p = 0.094, two-tailed) associated with the change in consensus, Δq, indicating that SEG is associated with a decrease in consensus; the Pearson correlations show no significant relations. These pairwise correlations do not indicate that BS and SCF are associated with a decrease in consensus, or that MEF is associated with an increase in consensus. However, these pairwise correlations should be interpreted with caution as they do not control for other determinants of analysts’ consensus. Results of examining changes in analyst consensus Columns (1) and (2) of Table 2 show our predictions from H1 and H2 and our results from estimating equation (1) respectively. Consistent with prior research (see Lang and Lundholm 1993, 1996; Barron et al. 2008), we use a decile rank specification in all of our regression analyses to mitigate the influence of skewness and outliers.11 All of the continuous variables are transformed to [0, 1] decile ranks (i.e., we rank the original variables into 0–9 deciles and then divide the ranks by 9). Our inferences are, however, robust to using regular rank regressions. We report p-values in parentheses based upon two-way (firm and calendar quarter) clustering; we report one-tailed (two-tailed) p-values for explanatory variables with (without) predictions. We find that balance sheets (BS) and segment disclosures (SEG) are both negatively associated with Δq (0.036 and 0.041, p = 0.032 and 0.020, one-tailed). Consistent with H1, these results suggest that balance sheet and segment disclosures are associated with a decrease in the degree to which analysts’ forecasts (of next quarter’s earnings) are based upon common information. However, we find no evidence that the disclosure of cash flow statements (SCF) is associated with a significant decrease in consensus (0.016, p = 0.805, one-tailed). Similarly, we find no evidence that the disclosure of management earnings forecasts (MEF) is associated with a significant increase in consensus (0.001, p = 0.467, one-tailed), providing no support for H2. To assess the economic significance of our findings, we benchmark the effects of balance sheet (BS) and segment (SEG) disclosures with those of the magnitude and sign of earnings surprises (|SURP| and SIGN, respectively). Table 2 shows that consistent with Barron et al. (2008), larger and negative earnings surprises are both associated with a decrease in analyst consensus (the coefficients on |SURP| and SIGN are both negative). 10. 11. The relatively low frequency of segment disclosures is partly due to the fact that our sample includes 156 earnings announcements from single segment firms (see also footnote 9). Our sample also has a relatively high frequency of management earnings forecasts. As a comparison, we merge the I/B/E/S and FirstCall databases and find that over our sample period about 27 percent of firm-quarters have at least one management earnings forecast issued on the earnings announcement date. The higher frequency of management earnings forecasts in our sample is likely because: (i) our sample contains relatively larger firms, which may be more likely to issue more management earnings forecasts or data providers like FirstCall may be more likely to collect forecasts by these firms (Chuk, Matsumoto, and Miller 2013); (ii) since analysts are more likely to revise their forecasts in response to management earnings forecasts, the data requirement for computing analyst consensus (three or more matched analysts before and after an earnings announcement) may tilt our sample more toward earnings announcements that contain management earnings forecasts; and (iii) management earnings forecasts are increasingly “bundled” with earnings announcements (Anilowski, Feng, and Skinner 2007; Rogers and Van Buskirk 2013). The raw dependent variables (i.e., BKLS variables and forecast errors) and control variables (|SURP| and SIZE) are highly skewed with a significant number of extreme values. CAR Vol. 34 No. 1 (Spring 2017) 354 Contemporary Accounting Research TABLE 2 Main regression analysis Main analysis Δq Additional analyses ΔCOMMON ΔPRIVATE ΔABSMFE Dependent variable: Predict (1) Financial disclosures BS SCF SEG MEF + Controls |SURP| SIGN SIZE BM Coeff. (p-value) (2) 0.036 (0.032) 0.016 (0.805) 0.041 (0.020) 0.001 (0.467) 0.055 (0.007) 0.029 (0.061) 0.025 (0.237) 0.033 (0.862) Calendar quarter fixed effects Adjusted R2 (%) Yes 0.75 Predict (3) ? ? ? + + + ? ? Coeff. (p-value) (4) 0.068 (0.001) 0.008 (0.644) 0.003 (0.857) 0.020 (0.041) 0.051 (0.095) 0.001 (0.476) 0.014 (0.449) 0.011 (0.693) Yes 1.97 Predict (5) + + + + + ? ? Coeff. (p-value) (6) 0.080 (<0.001) 0.016 (0.828) 0.052 (0.001) 0.002 (0.553) 0.057 (0.040) 0.035 (0.008) 0.021 (0.497) 0.021 (0.338) Yes 1.63 Predict (7) ? ? ? Coeff. (p-value) (8) 0.098 (<0.001) 0.027 (0.265) 0.043 (0.008) 0.015 (0.181) 0.147 (<0.001) 0.054 (0.001) 0.109 (<0.001) 0.014 (0.603) Yes 6.82 Notes: This table shows the results for our main regression analysis where we estimate equation (1) to examine the relation between the change in analyst consensus (Δq) around earnings announcements and the financial disclosures made with earnings announcements (BS, SCF, SEG, and MEF). This table also shows (i) the results of estimating equation (2), which examines the change in the precision of analysts’ common (ΔCOMMON) and private information (ΔPRIVATE) around earnings announcements, and (ii) the results of estimating equation (3), which examines the change in the absolute error in the mean forecast (ΔABSMFE) around earnings announcements. The financial disclosure variables are BS, SCF, SEG and MEF, and the control variables are |SURP|, SIGN, SIZE, and BM. See the Appendix for variable definitions. All regressions include calendar quarter fixed effects. Additionally, all models are estimated using decile rank regressions where all the continuous variables are transformed into [0,1] decile ranks by ranking the original variables into 0–9 deciles and then dividing the ranks by 9. The sample is comprised of 1,445 quarterly earnings announcements from 2003 to 2004. We report one-tailed p-values for explanatory variables where we make a directional prediction; otherwise we report two-tailed p-values. All p-values reported are based upon standard errors that use two-way (firm and calendar quarter) clustering. Tests comparing the coefficients on BS and SEG with those on |SURP| and SIGN indicate that they are not statistically different (two-tailed p-values = 0.60, 0.79, 0.62, and 0.64 for comparing BS with |SURP|, BS with SIGN, SEG with |SURP|, and SEG with SIGN, CAR Vol. 34 No. 1 (Spring 2017) Disclosures and Analysts’ Information 355 respectively). Since we estimate equation (1) using decile rank regressions, these results suggest that the impacts of balance sheet and segment disclosures (SEG or BS) on the change in consensus are comparable to those of a change from the bottom to the top decile (i.e., from decile 0 to decile 1) of absolute earnings surprise or a change in the sign of the earnings surprise. Results of examining changes in analysts’ common and private information In this subsection, we further examine the relation between the disclosure of financial statements and management earnings forecasts at earnings announcements and changes in the precision of analysts’ common and private information (COMMON and PRIVATE). BKLS show that COMMON and PRIVATE can be measured using the variance of analysts’ forecasts (D), the squared error in the mean forecast (SE), and the number of forecasts (N) as follows: COMMON ¼ SE D=N ½ð1 1=NÞD þ SE 2 and PRIVATE ¼ D ½ð1 1=NÞD þ SE2 : However, one caveat to keep in mind when using the precision measures of BKLS is that these measures require the additional assumption that all analysts possess private information of equal precision (see Barron et al. 2002). This additional assumption may not hold when analysts have unequal abilities or issue forecasts sequentially after observing other analysts’ forecasts. Using the same matched individual forecasts (of quarter q+1 earnings) used to calculate Δq, we estimate COMMON and PRIVATE before and after the quarter q earnings announcement and then calculate the change in COMMON and PRIVATE for firm i in quarter q, denoted ΔCOMMONiq and ΔPRIVATEiq. Consistent with prior research (e.g., Barron et al. 2008; Byard et al. 2011), for comparability across firms, we scale ΔCOM MONiq and ΔPRIVATEiq by their respective preannouncement levels. We examine the relation between the same financial disclosures (BS, SCF, SEG, and MEF) and changes in both the precision of analysts’ common and private information (ΔCOMMON and ΔPRIVATE) using the following model: DCOMMONiq or DPRIVATEiq ¼ u0 þ u1 BSiq þ u2 SCFiq þ u3 SEGiq þ u4 MEFiq þ CONTROLSiq þ eiq ; ð2Þ where CONTROLSiq refers to the same control variables used in equation (1). Panel A (B) of Table 1 shows descriptive statistics (correlations) for ΔCOMMON and ΔPRIVATE. Our hypotheses predict that BS, SCF and SEG are positively associated with ΔPRIVATE, and MEF is positively (negatively) associated with ΔCOMMON (ΔPRIVATE). Columns (3) to (6) of Table 2 report results from estimating equation (2) for both ΔCOMMON and ΔPRIVATE. We find that BS is significantly positively associated with both ΔCOMMON (0.068, p = 0.001, two-tailed) and ΔPRIVATE (0.080, p < 0.001, onetailed), suggesting that the disclosure of balance sheets increases the precision of both analysts’ common and private information. In contrast, SEG is significantly positively associated with ΔPRIVATE (0.052, p = 0.001, one-tailed) but is not significantly associated with ΔCOMMON (0.003, p = 0.857, two-tailed), suggesting that the disclosure of segment data increases the precision of analysts’ private information only.12 These results show that balance sheet and segment disclosures have different effects on the precision of analysts’ common vs. private information regarding upcoming quarterly earnings: balance sheet disclosures trigger an increase in both analysts’ common and private information, 12. These results are robust to restricting our sample to only multisegment reporting firms. CAR Vol. 34 No. 1 (Spring 2017) 356 Contemporary Accounting Research while segment disclosures primarily spur analysts’ private information production.13 However, these prior studies do not examine the effect of segment disclosures on changes in analysts’ common and private information. Additionally, we find that MEF is positively associated with ΔCOMMON (0.020, p = 0.041, one-tailed), providing evidence that management earnings forecasts help increase analysts’ common information regarding upcoming quarterly earnings. We find no evidence that the disclosure of cash flow statements is associated with changes in either analysts’ common or private information about next quarter’s earnings.14 Results of examining changes in analysts’ forecast accuracy Our analyses so far use the BKLS measures of analysts’ consensus and the precision of analysts’ common and private information. As discussed earlier, a potential concern using these measures is that the BKLS model assumes that differences in analysts’ earnings forecasts only reflect analysts’ private information; if, however, differences in analysts’ earnings forecasts reflect noise rather than private information, then a decrease in analyst consensus may reflect more idiosyncratic noise (rather than more private information) in analysts’ forecasts. Therefore, to test the robustness of our inferences based upon BKLS measures, we also examine changes in the accuracy of analysts’ average forecasts. If balance sheet, segment, and management earnings forecast disclosures increase analysts’ common and/or private information, then we would expect these disclosures to also be associated with an increase in analysts’ forecast accuracy. In contrast, if changes in the BKLS measures merely reflect noise or confusion on the part of analysts, then we would expect these disclosures to be associated with a decrease in the accuracy of analysts’ average forecasts. We test the association between the same earnings announcement disclosures and changes in the absolute error in analysts’ average forecasts (ΔABSMFE) using the following model: DABSMFEiq ¼ u0 þ u1 BSiq þ u2 SCFiq þ u3 SEGiq þ u4 MEFiq þ CONTROLSiq þ eiq ; ð3Þ where ΔABSMFEiq is the change in the absolute error in the mean forecast (using the same matched forecasts of quarter q+1 earnings made before and after the quarter q earnings announcement) around the quarter q earnings announcement, scaled by stock price at the end of quarter q. CONTROLS refers to the same control variables included in equations (1) and (2). Panel A (B) of Table 1 shows descriptive statistics (correlations) for ΔABSMFE. Based upon our findings for ΔCOMMON and ΔPRIVATE in Table 2, we expect BS, SEG and MEF to be negatively associated with ΔABSMFE (u1, u3, and u4 < 0). Our predictions and results from estimating equation (3) are shown in columns (7) and (8) of Table 2 respectively. Consistent with our expectations, we find that BS and SEG are both significantly negatively related with ΔABSMFE (0.098 and 0.043, p < 0.001 and p = 0.008, one-tailed, respectively), indicating that balance sheet and segment disclosures are associated with a decrease in the absolute error in the mean forecast, that is, an increase in the accuracy of analysts’ average forecasts. We also find that the coefficient on MEF is negative (0.015), though it is not significant at the conventional level (p = 0.181, one-tailed).15 We find no evidence that the disclosure of cash flow 13. 14. 15. This result is consistent with prior findings that segment disclosures improve analyst forecast accuracy (see Baldwin 1984; Swaminathan 1990; Duru and Reeb 2002; Berger and Hann 2003). However, Previts, Bricker, Robinson, and Young (1994) find that, in their research reports, analysts do sometimes discuss cash flow-related items and produce non-GAAP cash flow schedules (see also Asquith, Mikhail, and Au 2005; Brown, Call, Clement, and Sharp 2015). Note that tests of the effect of common information on mean forecast errors are less powerful than tests of the effect of private information. Equation (20) of BKLS (p. 427) shows that common information has relatively less of an effect on mean forecast errors because, unlike private information, common information contains error that is not diversified away from the mean forecast. CAR Vol. 34 No. 1 (Spring 2017) Disclosures and Analysts’ Information 357 statements (SCF) is negatively related to ΔABSMFE. These results using analysts’ forecast accuracy mitigate concerns that our inferences could be confounded by potential violations of assumptions underlying the BKLS model and that the decrease in BKLS consensus is driven by more noise in analysts’ forecasts. Overall, the results in Table 2 are consistent with balance sheet and segment disclosures playing an important part in analysts’ information interpretation role and analysts developing new insights regarding near-term earnings from interpreting and processing these disclosures. In contrast, we fail to find any significant relation between disclosures of cash flow statements and changes in analysts’ information regarding upcoming quarterly earnings. Our failure to find a significant relation for cash flow statement disclosures seems somewhat surprising. Cash flow statements are an important financial statement that standard setters believe conveys useful information to investors. There is also evidence that the cash flow statement is incrementally value-relevant (see Livnat and Zarowin 1990; Cheng, Liu, and Schaefer 1997). One possible explanation is that our tests do not have sufficient power to detect the effects of the disclosure of cash flow statements. Another possible explanation is that cash flow statements may not be a key input to analysts’ earnings forecasting models: when forecasting earnings, analysts may use a “balance sheet approach” that primarily focuses on information contained in the income statement and balance sheet. Consistent with such a “balance sheet approach,” analysts typically focus on earnings (e.g., EBITDA) and balance sheet items in their forecasting and valuation analyses, and financial statement analysis textbooks commonly emphasize balance sheet and income statement items in earnings forecasting models (see, e.g., Palepu and Healy 2008; Penman 2010). Additionally, while we find that disclosures of management earnings forecasts bundled with earnings announcements are associated with an increase in analysts’ common information regarding upcoming quarterly earnings, we fail to find strong evidence that they are associated with an increase in the accuracy of the mean forecast. One likely reason is that our tests may lack power due to our relatively smaller sample size compared with prior research and our focus on only bundled management earnings forecasts, which may be routine disclosures that are well anticipated by analysts and thus convey relatively less new information compared to nonbundled forecasts (see Rogers and Van Buskirk 2013).16,17 One caveat of our Table 2 tests is that our regression models have low explanatory power (the adjusted R2 is 0.75 percent, 1.97 percent, 1.63 percent, and 6.82 percent for the Δq, ΔCOMMON, ΔPRIVATE, and ΔABSMFE regressions, respectively), though we note that these low adjusted R2s are comparable with prior research using similar measures (e.g., Barron et al. 2008; Byard et al. 2011). Further comparisons of the adjusted R2s in Table 2 to “baseline” regressions (i.e., regressions including only control variables) 16. 17. We also examine management earnings forecasts issued at the end of fiscal quarters over the period of 1995–2011. Such forecasts can be more informative because they are more likely to be unexpected and are issued at a time when managers typically have more insider information regarding current period results. We identify management earnings forecasts issued in the 10-day window ending on each fiscal quarter-end (results are similar when we use a 5-day or 30-day window), and test the relation between the issuance of management earnings forecasts in this window and changes in analysts’ information. Using a large sample of 11,519 observations with required I/B/E/S/FirstCall/COMPUSTAT data for measuring analysts’ information, management forecast, and control variables, we find that the issuance of management earnings forecasts is associated with a significant increase in analysts’ common and private information and a significant decrease in analysts’ forecast errors (untabulated). To test whether our results for management earnings forecasts vary with managers’ forecast credibility, we rerun our tests allowing the coefficient on MEF to vary with prior management forecast accuracy (measured using management earnings forecasts issued over the prior quarter or the prior four quarters), and find that the coefficient on the interaction between MEF and the prior accuracy variables is insignificant (untabulated). CAR Vol. 34 No. 1 (Spring 2017) 358 Contemporary Accounting Research indicate that our test variables as a whole provide significant (marginal) incremental explanatory power for ΔPRIVATE and ΔABSMFE (Δq and ΔCOMMON).18 Results using alternative disclosure variables Our analyses so far are based upon indicator variables (BS, SCF, SEG and MEF) that identify the presence or absence of a disclosure in earnings announcements. We also examine multiple alternative disclosure measures that further take into account disclosure quality: • • For the balance sheet and cash flow statement disclosures, we create alternative measures (BS_ALT and SCF_ALT) which are defined as the number of line items in the disclosure included in the earnings announcement divided by the number of line items in the same disclosure included in the subsequent 10-K/Q filing (see D’Souza, Ramesh, and Shen 2010).19 We also include the number of line items in the income statement disclosed in the earnings announcement divided by the number of line items in the income statement disclosed in the subsequent 10-K/Q filing (IS_#LINES) as an additional control variable. We construct an alternative measure of management earnings forecasts (MEF_ALT) based upon forecast precision, which equals 4 for a point forecast, 3 for a range forecast, 2 for single-bound forecast, 1 for a qualitative forecast, and 0 if no forecast is provided.20 Table 3 reports the results of reestimating equation (1) using the above alternative disclosure measures. The results are similar to our main results using indicator variables.21 5. Additional analysis of the content of the Q&A section of conference calls Our main analyses focus on analysts’ information about upcoming quarterly earnings. To provide more general evidence on analysts’ informational role as it relates to earnings announcement disclosures, we also examine the relation between earnings announcement disclosures and the content of the questions-and-answers (Q&A) section of conference calls. Conference calls have become a standard disclosure medium for public companies over the past two decades. Prior research finds that the Q&A section of conference calls, in particular, conveys useful information to analysts (Tasker 1998; Hollander, Plonk, and Roelofsen 2010; Matsumoto, Pronk, and Roelofsen 2011). Participation in the Q&A section of conference calls has been shown to be important to an analyst’s own analysis and private information production (Mayew 2008; Mayew, Sharp, and Venkatachalam 2012). Because it affords analysts an opportunity to question management, the Q&A section of 18. 19. 20. 21. The adjusted R2s of the baseline regressions (two-tailed p-value from the Vuong test comparing the Table 2 regressions with their corresponding baseline regressions) are: 0.58 percent (0.21), 1.34 percent (0.10), 0.75 percent (0.02), and 5.68 percent (0.01) for Δq, ΔCOMMON, ΔPRIVATE, and ΔABSMFE, respectively. For cash flow statement disclosures, we also test a second alternative measure based upon the preparation method. Cash flow statements prepared using the direct method are more likely to convey new information incremental to balance sheets and income statements. We create a new measure equal to 2 if the direct method is used, 1 if the indirect method is used, and 0 if no cash flow statement is disclosed at the earnings announcement. Of the 728 cash flow statement disclosures in our sample, 3 (725) are prepared using the direct (indirect) method. Our inferences remain unchanged using this alternative measure for cash flow statement disclosures. Among the 774 management earnings forecast disclosures in our sample, 80 are point forecasts, 573 are range forecasts, 2 are single-bound forecasts, and 119 are qualitative forecasts. Results are similar if we group single-bound forecasts with either range forecasts or with qualitative forecasts. We also reestimate equations (2) and (3) using these alternative disclosure measures and find similar results. CAR Vol. 34 No. 1 (Spring 2017) Disclosures and Analysts’ Information 359 TABLE 3 Results using alternative disclosure measures Predict Financial disclosures BS_ALT SCF_ALT SEG MEF_ALT + Controls |SURP| SIGN SIZE BM IS_#LINES ? Calendar quarter fixed effects Adjusted R2 (%) Δq Coeff. (p-value) 0.055 (0.051) 0.011 (0.691) 0.040 (0.043) 0.002 (0.333) 0.054 (0.009) 0.028 (0.063) 0.024 (0.247) 0.037 (0.897) 0.126 (0.863) Yes 0.82 Notes: This table shows the results of reestimating equation (1) using alternative measures of the financial disclosures (i.e., disclosures of balance sheets, statements of cash flows, segment data, and management earnings forecasts) made with earnings announcements. The dependent variable is the change in analyst consensus (Δq). For the financial disclosure variables, we replace BS with BS_ALT, SCF with SCF_ALT, and MEF with MEF_ALT. See the Appendix for variable definitions. All regressions include calendar quarter fixed effects. Additionally, all models are estimated using decile rank regressions where all the continuous variables are transformed into [0,1] decile ranks by ranking the original variables into 0–9 deciles and then dividing the ranks by 9. The sample is comprised of 1,445 quarterly earnings announcements from 2003 to 2004. We report one-tailed p-values for explanatory variables where we make a directional prediction; otherwise we report two-tailed p-values. All p-values reported are based upon standard errors that use two-way (firm and calendar quarter) clustering. conference calls provides a rare opportunity for researchers to observe the types of information analysts are seeking. Since analysts are typically only allowed to ask a limited number of questions, it is natural to expect analysts to ask questions related to the most important information they need for their forecasting and valuation tasks. If a disclosure provides important inputs to analysts’ forecasting or valuation models and analysts focus on interpreting the disclosure, then we expect the disclosure to trigger more related discussion in the Q&A section of conference calls. If, for example, balance sheet disclosures are used as an important input in any of analysts’ models and analysts can extract new insights from interpreting balance sheet disclosures, then we expect balance sheet CAR Vol. 34 No. 1 (Spring 2017) 360 Contemporary Accounting Research disclosures to be associated with more analysts questioning management about the content of the balance sheet in the Q&A section of conference calls. Because analysts can ask questions to extract information they need for any of their forecasting and valuation tasks (rather than just forecasting next quarter’s earnings), this conference call analysis complements our main tests by providing more general evidence on the relation between earnings announcement disclosures and analysts’ information interpretation role. All earnings announcements in our sample are accompanied by a conference call. To measure the content of the Q&A section of conference calls related to financial statement disclosures, we first analyze the text of financial statement disclosures (e.g., the balance sheet disclosure) to generate lists of the most common keywords and phrases that occur exclusively in each type of financial statement disclosure.22 Next, we use a PERL program to search the transcripts of the Q&A section of conference calls to identify the number of times these keywords and phrases occur in the Q&A section of conference calls. This yields four numerical scores (CCQA_BS, CCQA_SCF, CCQA_SEG, and CCQA_IS) that represent the number of times the most common keywords or phrases contained in balance sheets, cash flow statements, segment data, and income statements disclosed in earnings announcements occur in the Q&A section of conference calls. To identify analysts questioning management regarding management earnings forecasts, we first apply a search string similar to Chuk et al. (2013, footnote 1) to the transcript of the Q&A section of conference calls to identify possible places containing discussions about management earnings forecasts; we then manually check each place to identify analysts questioning managements regarding a management earnings forecast. We create an indicator variable (CCQA_MEF) equal to one if the conference call Q&A includes analysts questioning management about a management earnings forecast (e.g., questions about earnings “guidance”). To examine the relation between financial disclosures and the content of the Q&A section of conference calls, we estimate the following OLS (CCQA_BS/SCF/SEG) or logistic (CCQA_MEF) model: CCQA BSiq ; CCQA SCFiq ; CCQA SEGiq or CCQA MEF ¼ d0 þ d1 BSiq þ d2 SCFiq þ d3 SEGiq þ d4 MEFiq þ CONTROLSiq þ eiq ; ð4Þ where CONTROLS includes the control variables used in equations (1–3), the word count of the Q&A section of conference calls (CCQA_#WORDS), and the word count for the number of unique income statement-related terms in the conference call Q&A (CCQA_IS). Table 4 shows the results for estimating equation (4). Columns (1) and (3) show that BS is significantly positively related to CCQA_BS (0.180, p < 0.001, two-tailed), and SEG is significantly positively related to CCQA_SEG (0.152, p < 0.001, two-tailed), indicating that balance sheet and segment disclosures are associated with more analysts questioning and management discussion related to these disclosures in the conference call Q&A. Further, column (4) shows that MEF is significantly positively related to CCQA_MEF (0.577, p = 0.035, two-tailed), indicating that disclosures of management earnings forecasts are associated with a higher likelihood of analysts questioning management about a management earnings forecast in the conference call Q&A. In contrast, column (2) shows no evidence that the disclosure of cash flow statements (SCF) is related to analysts questioning and management discussion of cash flow statement items (CCQA_SCF) in the conference call Q&A. These results are consistent with disclosures of balance sheets, segment data 22. Please see supporting information, “Appendix S1: Creation of Unique Word/Phrase Lists for Each Financial Disclosure” as an addition to the online article for details of the method we use to identify the keywords/phrase and the lists of the unique words/phrases. CAR Vol. 34 No. 1 (Spring 2017) Disclosures and Analysts’ Information 361 TABLE 4 Association between financial disclosures and the content of the conference call Q&A Dependent variables: Financial disclosures BS SCF SEG MEF Controls |SURP| SIGN SIZE BM CCQA_#WORDS CCQA_IS Calendar quarter fixed effects Adjusted R2 (%) Pseudo R2 (%) CCQA_BS Coefficient (p-value) (1) CCQA_SCF Coefficient (p-value) (2) CCQA_SEG Coefficient (p-value) (3) CCQA_MEF Coefficient (p-value) (4) 0.180 (<0.001) 0.017 (0.468) 0.001 (0.950) 0.029 (0.138) 0.017 (0.505) 0.025 (0.158) 0.014 (0.494) 0.001 (0.948) 0.051 (0.065) 0.032 (0.124) 0.152 (<0.001) 0.005 (0.651) 0.056 (0.888) 0.149 (0.580) 0.390 (0.298) 0.577 (0.035) 0.111 (<0.001) 0.008 (0.703) 0.086 (0.030) 0.153 (<0.001) 0.125 (<0.001) 0.051 (0.092) Yes 11.31 0.010 (0.761) 0.040 (0.049) 0.002 (0.944) 0.010 (0.737) 0.055 (0.064) 0.077 (0.008) Yes 1.55 0.026 (0.195) 0.038 (0.003) 0.116 (<0.001) 0.009 (0.397) 0.136 (<0.001) 0.365 (<0.001) Yes 14.91 0.522 (0.218) 0.658 (0.053) 0.303 (0.944) 0.030 (0.944) 0.257 (0.550) 0.500 (0.245) Yes 4.03 Notes: This table shows the results from estimating equation (4), which tests the association between the content of the questions-and-answers (Q&A) section of earnings conference calls and the financial disclosures made with earnings announcements. See the Appendix for variable definitions. All regressions include calendar quarter fixed effects. Additionally, we estimate equation (4) as an OLS (for CCQA_BS/SCF/SEG) or a logistic model (for CCQA_MEF) using decile rank regressions where all the continuous variables are transformed into [0,1] decile ranks by ranking the original variables into 0–9 deciles and then dividing the ranks by 9. The sample is comprised of 1,445 quarterly earnings announcements from 2003 to 2004. We report one-tailed p-values for explanatory variables where we make a directional prediction; otherwise we report two-tailed p-values. All p-values reported are based upon standard errors that use two-way (firm and calendar quarter) clustering. and management earnings forecasts generally providing useful inputs for analysts’ research, and analysts performing an information interpretation role with respect to these disclosures. Consistent with our main analyses using analysts’ earnings forecasts, our conference call analysis yields no evidence that analysts perform a similar information interpretation role with respect to cash flow statement disclosures. Further comparison of the adjusted R2s in Table 4 to the baseline regressions with only control variables indicates CAR Vol. 34 No. 1 (Spring 2017) 362 Contemporary Accounting Research that our test variables provide significant incremental explanatory power for CCQA_BS and CCQA_SEG.23,24 6. Robustness analyses Controlling for other disclosures made with earnings announcements Our analyses so far focus on the disclosure of financial statements and management earnings forecasts. However, firms also include many other supplemental disclosures in their earnings announcements (see Watts 1973; Kane, Lee, and Marcus 1984; Hoskin, Hughes, and Ricks 1986; Brown and Kim 1993; Kerstein and Kim 1995; Amir and Lev 1996; Chen et al. 2002; Wasley and Wu 2006). To ensure that our results are not driven by omitting some other disclosures made with earnings announcements, we also hand-collect data from earnings announcement press releases for an additional 16 qualitative disclosures firms may include in their earnings announcements.25 In addition, we also control for the tone of language used in earnings announcement press releases using the measure developed by Davis, Piger, and Sedor (2012). These additional 17 disclosure/tone variables are listed in panel A of Table 5 and defined in the Appendix. Panel A of Table 5 shows the descriptive statistics for these additional 17 disclosure/ tone variables. Few qualitative disclosures are common. For example, 18.3 percent of earnings announcements include a discussion of production-related issues (the mean value of this variable is 0.183). Panel B of Table 5 shows the results of reestimating equation (1) after including these additional 17 disclosure/tone variables as additional controls. We find that our main results continue to hold. We also reestimate equations (2)–(4) including those additional disclosure/tone variables and find that our inferences remain unaffected (untabulated).26 Controlling for the endogeneity of disclosures The earnings announcement disclosures we examine are endogenously determined, raising concerns that our results may be confounded by some correlated omitted variable problem. To mitigate this concern, we examine the robustness of our findings to controlling for a variety of firm characteristics and to correcting for self-selection using a two-stage Heckman model. Theory suggests a number of underlying factors that determine firms’ disclosure policy choices, including: (i) the level of uncertainty; (ii) fundamental firm characteristics like firm 23. 24. 25. 26. The adjusted R2s of the baseline regressions (two-tailed p-value from the Vuong test comparing the Table 4 regressions with the baseline regressions) are: 7.19 percent (<0.01), 1.53 percent (0.95), and 9.70 percent (<0.01) for CCQA_BS, CCQA_SCF, and CCQA_SEG, respectively. The pseudo R2 for the baseline regression for CCQA_MEF is 3.78 percent. As another additional test, we also consider the relation between the inclusion of forecasts of financial statements in analysts’ research reports and the disclosure of the same financial statements in firms’ earnings announcements. For an announcement including a particular statement, issuance of a forecast of this statement by analysts only before (after) the announcement would be more consistent with an information discovery (interpretation) role. We randomly select 100 announcements from our sample, and hand-collect matched analysts’ reports issued before and after these announcements from the ThomsonOne database. We find little variation in the inclusion of financial statement forecasts between an analyst’s preannouncement reports and her post-announcement reports. In addition to these 16 items, we also collected data for the disclosure of (i) comprehensive income, and (ii) a new restatement. We find only one (six) earnings announcement that includes a statement of comprehensive income (a restatement announcement). Our results are robust to controlling for these two additional disclosures. Our results are unlikely to be driven by the fair value disclosures included in balance sheets. Of the 1,445 earnings announcements in our sample, only one announcement includes a statement of comprehensive income, and only 13 include a discussion of changes in fair values. Results are similar if we exclude these observations. CAR Vol. 34 No. 1 (Spring 2017) Disclosures and Analysts’ Information 363 TABLE 5 Analysis including additional qualitative disclosure variables Panel A: Univariate statistics for additional qualitative disclosure variables Fair Value Back Order Capex Dividends Stock Split Cash Flow Forecast Revenue Forecast Restatement Litigation New Products Restructuring Unusual Items Accounting Changes Shipment Contract Issues Production Issues NETOPT Mean SE 25th percentile Median 75th percentile 0.009 0.063 0.070 0.006 0.006 0.019 0.162 0.004 0.046 0.018 0.089 0.009 0.003 0.080 0.109 0.183 0.993 0.094 0.243 0.255 0.079 0.078 0.138 0.369 0.064 0.209 0.133 0.284 0.094 0.058 0.271 0.311 0.387 0.737 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.498 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.900 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 1.364 Panel B: Reestimating equation (1) including controls for additional qualitative disclosure variables Dependent variable: Δq Financial disclosures BS SCF SEG MEF Controls |SURP| SIGN SIZE BM Additional qualitative disclosure variables Fair Value Back Order Capex Dividends Stock Split Cash Flow Forecast Revenue Forecast Restatement Litigation New Products Restructuring Unusual Items Predict Coefficient p-value + 0.028 0.017 0.038 0.000 0.068 0.843 0.036 0.518 0.061 0.029 0.017 0.037 0.006 0.076 0.285 0.947 0.070 0.042 0.031 0.011 0.047 0.055 0.003 0.003 0.036 0.009 0.010 0.060 0.448 0.393 0.371 0.937 0.516 0.360 0.869 0.978 0.246 0.909 0.801 0.518 (The table is continued on the next page.) CAR Vol. 34 No. 1 (Spring 2017) 364 Contemporary Accounting Research TABLE 5 (continued) Panel B: Reestimating equation (1) including controls for additional qualitative disclosure variables Dependent variable: Δq Predict Accounting Changes Shipment Contract Issues Production Issues NETOPT Calendar quarter fixed effects Adjusted R2 (%) Coefficient p-value 0.132 0.006 0.039 0.036 0.013 Yes 0.19 0.130 0.820 0.246 0.205 0.655 Notes: This table shows the results from reestimating equation (1) after including additional control variables for qualitative disclosures firms may include in their earnings announcements. The dependent variable is Δq, the change in analyst consensus. See the Appendix for variable definitions. All regressions include calendar quarter fixed effects. Additionally, all models are estimated using decile rank regressions where all the continuous variables are transformed into [0,1] decile ranks by ranking the original variables into 0–9 deciles and then dividing the ranks by 9. The sample is comprised of 1,445 quarterly earnings announcements from 2003 to 2004. We report one-tailed p-values for explanatory variables where we make a directional prediction; otherwise we report two-tailed p-values. All p-values reported are based upon standard errors that use two-way (firm and calendar quarter) clustering. size (i.e., market capitalization); (iii) firm complexity; (iv) firm performance; (v) performance variability; (vi) proprietary costs; and (vii) whether or not a firm is about to issue stock. Following prior studies (e.g., Lang and Lundholm 1993; Tasker 1998; Chen et al. 2002; Miller 2002; Botosan and Stanford 2005; Francis, Nanda, and Olsson 2008), we construct a total of 17 variables that proxy for these underlying factors that determine firms’ disclosure policy choices (these additional firm characteristics are listed in Table 6; see the Appendix for variable definitions). Requiring data to measure these additional controls reduces our sample to 1,258 earnings announcements. We first reestimate equation (1) after including these additional controls. As shown in Table 6, our main results continue to hold. We also estimate two-stage Heckman models to correct for potential endogeneity of the disclosures, and find that our inferences remain unchanged (untabulated).27 These results mitigate concerns that our findings are affected by the endogeneity or self-selection of disclosures. Additional robustness tests Our results still hold when we: • 27. Control for information leakage by including the number of days between the earnings announcement date and the 10-K/Q filing date, the actual (raw or market adjusted) returns between these two dates, or both. In the first stage, we estimate a probit model for each of the four disclosure variables (BS, SEG, SCF and MEF) as a function of the control variables in equation (1) plus the additional 17 firm characteristics (defined in the Appendix), and construct an inverse Mills ratio for each of the four variables (see Heckman 1979). In the second stage, we then reestimate equation (1) including these four inverse Mills ratios (e.g., see Song 2004). CAR Vol. 34 No. 1 (Spring 2017) Disclosures and Analysts’ Information 365 TABLE 6 Reestimating equation (1) controlling for firm characteristics that determine firms’ disclosure policy Dependent variable: Δq Predict Financial disclosures BS SCF SEG MEF + Controls |SURP| SIGN SIZE BM Firm characteristics (that determine firms’ disclosure policy) LOSS DISP RET_VOL ROA A_CAR Q_CAR QTRS_UP FOLLOW HTECH AGE #_SEG AQ CORR_ER IND_HHI IND_PROFITADJ M&A ISSUE Include calendar quarter fixed effects Adjusted R2 (%) Coefficient p-value 0.040 0.021 0.043 0.004 0.073 0.816 0.034 0.463 0.103 0.040 0.105 0.024 0.003 0.007 0.036 0.714 0.011 0.109 0.089 0.011 0.037 0.050 0.019 0.040 0.042 0.043 0.023 0.039 0.017 0.040 0.012 0.029 0.049 Yes 1.53 0.614 0.002 0.041 0.772 0.403 0.386 0.283 0.509 0.166 0.234 0.360 0.207 0.591 0.163 0.827 0.289 0.657 Notes: This table shows the results from reestimating equation (1) after including additional control variables for firm characteristics that determine firms’ disclosure choices. See the Appendix for variable definitions. All regressions include calendar quarter fixed effects. Additionally, all models are estimated using decile rank regressions where all the continuous variables are transformed into [0,1] decile ranks by ranking the original variables into 0–9 deciles and then dividing the ranks by 9. The sample consists of 1,258 quarterly earnings announcements (requiring data to calculate the additional 17 controls reduces the sample size from 1,445 quarterly earnings announcements). We report one-tailed p-values for explanatory variables where we make a directional prediction; otherwise we report two-tailed p-values. All p-values reported are based upon standard errors that use are two-way (firm and calendar quarter) clustering. • Control for pro forma reporting by including a dummy variable for the presence of a reconciliation between pro forma and GAAP in the earnings announcement press release. CAR Vol. 34 No. 1 (Spring 2017) 366 • • • • • Contemporary Accounting Research Split our samples into larger and smaller firms (based upon median market capitalization) and rerun our analyses separately for the two subsamples. We find that our results are similar across both subsamples, mitigating concerns that our results are driven only by very large firms and may not generalize to smaller firms. Use I/B/E/S split-adjusted data to construct our BKLS and forecast accuracy variables. Include additional management earnings forecasts disclosed in conference calls. We also collect data for new management earnings forecasts disclosed in conference calls and recode the MEF variable one if either the earnings announcement press release or the conference call transcript contains a management earnings forecast. Use unscaled COMMON and PRIVATE or scale the change in COMMON and PRIVATE by stock price (rather than scale by their respective preannouncement levels). Adjust standard errors in the regressions using two-way clustering by firm and year (rather than clustering on firm and calendar quarter). 7. Conclusion This study examines the relation between disclosures of financial statements and management earnings forecasts at earnings announcements and changes in analysts’ information about future earnings. Using a sample of 1,445 earnings announcements, we find that balance sheet and segment disclosures are associated with an increase in the degree to which analysts’ forecasts of upcoming quarterly earnings are based on private information. Further analyses show that balance sheet disclosures are associated with an increase in the precision of both analysts’ common and private information, segment disclosures are associated with an increase in the precision of analysts’ private information, and management earnings forecasts are associated with an increase in analysts’ common information. We also find that balance sheet and segment disclosures are associated with an increase in the accuracy of analysts’ average forecasts. In contrast, we fail to find evidence that the disclosure of cash flow statements is associated with changes in analysts’ information about upcoming quarterly earnings. These results are consistent with analysts processing balance sheet and segment disclosures at earnings announcements into new private information regarding upcoming quarterly earnings. Additional analysis of the questions-and-answers (Q&A) section of conference calls shows that disclosures of balance sheets, segment data, and management earnings forecasts are all associated with more related discussion in the conference call Q&A, consistent with these disclosures enhancing the information interpretation role of analyst research in general. Our study increases our understanding of the relation between financial disclosures and the informational role of financial analysts. To the extent that our tests have sufficient power, our failure to find a significant relation between the disclosure of cash flow statements and analysts’ information could suggest that cash flow statement disclosures may not be an important input to analysts’ forecasting and valuation models. One possibility is that analysts primarily use a “balance sheet approach” (e.g., see Palepu and Healy 2008; Penman 2010) to predict earnings, which tends to focus on the information contained in balance sheets and income statements. However, it remains unclear whether analysts use such a balance sheet approach because cash flow statements do not provide significant information about future earnings incremental to balance sheets (in combination with income statements), or analysts fail to fully understand and use the information contained in cash flow statements when forecasting earnings. CAR Vol. 34 No. 1 (Spring 2017) Disclosures and Analysts’ Information 367 Appendix Definition of variables Main dependent variables Δq Change in analyst consensus (q), which measures the degree to which analysts’ forecasts are based on common (public) information. BKLS express q in terms of the variance of forecasts (D), the squared error in the mean forecast (SE), and the number of forecasts (N) (see Barron et al., 1998, 426, SED=N Proposition 2) as follows: q ¼ ð11=N ÞDþSE : Using three or more forecasts of quarter q+1 earnings that are matched before and after the quarter q earnings announcement, we calculate q (for q+1 earnings) both before and after the quarter q earnings announcement. Therefore, Δq is the change in q regarding quarter q+1 earnings around the quarter q earnings announcement ΔCOMMON and Change in the precision of analysts’ common and private information calculated ΔPRIVATE using the BKLS model. COMMON and PRIVATE are expressed in terms of the variance of forecasts (D), the squared error in the mean forecast (SE), and the number of forecasts (N) (see Barron et al., 1998, 428, Corollary 1) SED=N as follows: COMMON ¼ ½ð11=N and PRIVATE ¼ ½ð11=NDÞDþSE2 : ÞDþSE2 Using three or more matched analysts’ forecasts (of quarter q+1 earnings) made before and after the quarter q earnings announcement, we estimate COMMON and PRIVATE (for quarter q+1 earnings) both before and after the quarter q earnings announcement and then compute the change in COMMON and PRIVATE (i.e., ΔCOMMON and ΔPRIVATE). We scale ΔCOMMON and ΔPRIVATE by their preannouncement levels for comparability across firms ΔABSMFE Change in the absolute error in the mean forecast of quarter q+1 earnings around the quarter q earnings announcement, scaled by stock price. Using three or more forecasts of quarter q+1 earnings that are matched before and after the quarter q earnings announcement, we first calculate the change in the absolute error in the mean forecast (of quarter q+1 earnings) around the quarter q earnings announcement. We then scale this change in the absolute error in the mean forecast by stock price at the end of quarter q Financial disclosure variables BS Indicator variable equal to one if the quarter q earnings announcement press release contains a balance sheet, and zero otherwise SCF Indicator variable equal to one if the quarter q earnings announcement press release contains a statement of cash flows, and zero otherwise SEG Indicator variable equal to one if the quarter q earnings announcement press release contains segment data, and zero otherwise MEF Indicator variable equal to one if the quarter q earnings announcement press release contains a management earnings forecast, and zero otherwise Main control variables |SURP| Calculated as: j Actual EPS Mean EPS Forecast j = Stock Price; where actual and forecasted EPS are for quarter q earnings. The mean forecast is calculated as the mean of the forecasts of quarter q earnings made in the 45-day period before the quarter q earnings announcement. Stock price is at the end of quarter q (The Appendix is continued on the next page.) CAR Vol. 34 No. 1 (Spring 2017) 368 Contemporary Accounting Research Indicator variable equal to one if the earnings surprise for quarter q is negative (i.e., if the quarter q actual earnings is less than the mean forecast made in the 45-day period before the quarter q earnings announcement), and zero otherwise SIZE Market capitalization (in $m) at the end of quarter q BM Book-to-market ratio at the end of quarter q Alternative disclosure measures BS_ALT The ratio of the number of line items in the balance sheet disclosed in the quarter q earnings announcement press release to the number of line items in the balance sheet disclosed in the subsequent 10-K/Q filing for quarter q (see D’Souza et al. 2010) SCF_ALT The ratio of the number of line items in the cash flow statement disclosed in the quarter q earnings announcement press releases to the number of line items in the cash flow statement disclosed in the subsequent 10-K/Q filing for quarter q (see D’Souza et al. 2010) MEF_ALT Coded 4 for point forecasts, 3 for range forecasts, 2 for single bound forecasts, 1 for qualitative forecasts, 0 if no management earnings forecast is disclosed in the quarter q earnings announcement press release IS_#LINES Control variable that is the number of line items in the income statement included in the quarter q earnings announcement press release scaled by the number of line items in the income statement in the subsequent 10K/Q for quarter q (see D’Souza et al. 2010) Variables used in the conference call Q&A analysis CCQA_BS Number of times the most common keywords and phrases that are exclusive to the balance sheet (e.g., “assets”) occur in the Q&A section of the quarter q conference call CCQA_SCF Number of times the most common keywords and phrases that are exclusive to the statement of cash flows (e.g., “cash flows”) occur in the Q&A section of the quarter q conference call CCQA_SEG Number of times the most common keywords and phrases that are exclusive to segment disclosures (e.g., “segments”) occur in the Q&A section of the quarter q conference call CCQA_MEF Indicator variable coded one (zero) if the Q&A section of the quarter q conference call includes at least one instance where analysts question management about a management earnings forecast (e.g., a question about earnings “guidance”) CCQA_#WORDS Total word count of the Q&A section of the quarter q conference call CCQ&A_IS Control variable that is a word count for the number of times the most common keywords and phrases that are exclusive to the income statement (e.g., “profit”) occur in the Q&A section of the quarter q conference call Additional qualitative disclosure variables Fair Value Indicator variable coded one if the quarter q earnings announcement press release includes an explanation of the change in Accumulated Other Comprehensive Income (AOCI) on the Balance Sheet (i.e., an explanation of the changes in fair values going through AOCI), and zero otherwise Back Order Indicator variable coded one if the quarter q earnings announcement press release includes a discussion of customer backorders, zero otherwise Capex Indicator variable coded one if the quarter q earnings announcement press release includes a discussion of capital expenditures, zero otherwise SIGN (The Appendix is continued on the next page.) CAR Vol. 34 No. 1 (Spring 2017) Disclosures and Analysts’ Information 369 Indicator variable coded one if the quarter q earnings announcement press release includes an announcement of dividend changes, and zero otherwise Stock Split Indicator variable coded one if the quarter q earnings announcement press release includes an announcement of a stock split, and zero otherwise Cash Flow Forecast Indicator variable coded one if the quarter q earnings announcement press release includes a forecast of future cash flows, and zero otherwise Revenue Forecast Indicator variable coded one if the quarter q earnings announcement press release includes a forecast of future revenue, and zero otherwise Restatement Indicator variable coded one if the quarter q earnings announcement press release includes a discussion of an accounting restatement, and zero otherwise Litigation Indicator variable coded one if the quarter q earnings announcement press release includes a discussion of ongoing litigation issues, and zero otherwise New Products Indicator variable coded one if the quarter q earnings announcement press release includes a discussion of new product(s), and zero otherwise Restructuring Indicator variable coded one if the quarter q earnings announcement press release includes a discussion of an ongoing restructuring, divestiture, or discontinued operation, and zero otherwise Unusual Items Indicator variable coded one if the quarter q earnings announcement press release includes a discussion of unusual items, and zero otherwise Accounting Changes Indicator variable coded one if the quarter q earnings announcement press release includes a discussion of a change in accounting policies, and zero otherwise Shipment Indicator variable coded one if the quarter q earnings announcement press release includes a discussion of customer shipments, and zero otherwise Contract Issues Indicator variable coded one if the quarter q earnings announcement press release includes a discussion of significant customer or supplier contract issues (e.g., a defense contractor), and zero otherwise Production Indicator variable coded one if the quarter q earnings announcement press release includes a discussion of ongoing production-related issues, and zero otherwise NETOPT Percentage of optimistic words (including praise, satisfaction and inspiration words listed by DICTION) minus the percentage of pessimistic words (including blame, hardship, and denial words listed by DICTION) in the quarter q earnings announcement press release, measured as a percentage. See Davis et al. (2012) Additional control variables for firm characteristics that determine firms’ disclosure policy LOSS Indicator variable if the quarter q earnings announcement reports a loss DISP Dispersion of analysts’ forecasts prior to the quarter q earnings announcement, defined as the coefficient of variation in analysts’ earnings forecasts RET_VOL Return volatility in quarter q, measured as the standard deviation of daily stock returns over the 253 trading days (1 calendar year) ending 2 trading days prior to the quarter q earnings announcement ROA Return on assets (ROA) for quarter q A_CAR Market-adjusted returns for the 253 trading days ending 2 trading days before the quarter q earnings announcement Q_CAR Quarterly market-adjusted returns over the 64 trading days ending 2 trading days before the quarter q earnings announcement QTRS_UP Number of (historic) quarters of continuous increasing seasonally-adjusted earnings prior to quarter q Dividends (The Appendix is continued on the next page.) CAR Vol. 34 No. 1 (Spring 2017) 370 Contemporary Accounting Research FOLLOW HTECH AGE #_SEG AQ CORR_ER IND_HHI IND_PROFITADJ M&A ISSUE Number of analysts that issue forecasts of quarter q earnings within a 45-day window prior to the quarter q earnings announcement Indicator variable equal to one for firms in a high-tech industry (4-digit SIC: 2833–2836 (Drugs), 8731–8734 (R&D Services), 7371–7379 (Software), 3570–3577 (Computers), 3600–3674 (Electronics), 3810–3845 (Instruments)) Number of years, by the quarter q earnings announcement, since a firm first went public Number of business segments reported by a firm Accruals quality, measured by McNichols’ (2002) modification of Dechow and Dichev’s (2002) model. We estimate the model for each firm using 10 years of data prior to the year of the quarter q earnings announcement. The standard deviation of the residuals from these firm-specific model estimates yields the firm-specific estimates of AQ Correlation between annual earnings and returns, measured as the adjusted R2 from firm-specific regressions of annual returns on the level of earnings and the change in earnings over the year using a 10-year window prior to the year of the quarter q earnings announcement (Francis, LaFond, Olsson, and Schipper 2004) Fitted Herfindahl-Hirschman Index (HHI) index as computed by Hoberg and Phillips (2010) for an industry (3-digit SIC codes). See also Dhaliwal, Huang, Khurana, and Pereira (2014) Persistence in the deviation of a firm’s return on assets (ROA) from the industry average ROA from estimating the following model (Botosan and Stanford 2005): ROA_ADJt = a0 + a1Dn 9 ROA_ADJt-1 + a2Dp 9 ROA_ADJt-1 + et, where ROA_ADt is the firm’s ROA in year t minus the average industry ROA (3-digit SIC code) in year t, Dn (Dp) is an indicator variable equal to one if ROA_ADJt-1 ≤ 0 (ROA_ADJt-1 > 0), and 0 otherwise. The model is estimated separately for each industry using the three years of data prior to the year of the quarter q earnings announcement. IND_PROFITADJA is equal to the estimate of a2 Indicator variable equal to one if a firm reports a merger or acquisition in quarter q, and zero otherwise Indicator variable for the presence of a common stock issuance in quarter q. Following Francis et al. (2008), we measure ISSUE as equal to one if the number of split-adjusted common shares outstanding increases by 20 percent or more in quarter q relative to quarter q1, and zero otherwise References Abarbanell, J. S., and B. J. Bushee. 1997. Fundamental analysis, future earnings, and stock prices. Journal of Accounting Research 35 (1): 1–24. Abarbanell, J. S., and B. J. Bushee. 1998. Abnormal returns to a fundamental analysis strategy. The Accounting Review 73 (1): 19–45. Altinkilicß, O., and R. Hansen. 2009. On the information role of stock recommendation revisions. Journal of Accounting and Economics 48 (1): 17–36. Amir, E., and B. Lev. 1996. Value-relevance of nonfinancial information: The wireless communications industry. Journal of Accounting and Economics 22 (1–3): 3–30. Anilowski, C., M. Feng, and D. Skinner. 2007. Does guidance affect market returns? The nature and information content of aggregate earnings guidance. Journal of accounting and Economics 44 (1– 2): 36–63. Asquith, P., M. B. Mikhail, and A. S. Au. 2005. Information content of equity analyst reports. Journal of Financial Economics 75 (2): 245–82. CAR Vol. 34 No. 1 (Spring 2017) Disclosures and Analysts’ Information 371 Ayers, B. C., and R. N. Freeman. 2003. Evidence that analyst following and institutional ownership accelerate the pricing of future earnings. Review of Accounting Studies 8 (1): 47–67. Baldwin, B. A. 1984. Segment earnings disclosures and the ability of security analysts to forecast earnings per share. The Accounting Review 59 (3): 376–89. Barron, O. E., O. Kim, S. C. Lim, and D. E. Stevens. 1998. Using analysts’ forecasts to measure properties of analysts’ information environment. The Accounting Review 73 (4): 421–33. Barron, O. E., D. Byard, and O. Kim. 2002. Changes in analysts’ information around earnings announcements. The Accounting Review 77 (4): 821–46. Barron, O. E., D. Byard, C. Kyle, and E. J. Riedl. 2002. High technology intangibles and analysts’ forecasts. Journal of Accounting Research 40 (2): 289–312. Barron, O. E., D. Byard, and Y. Yu. 2008. Earnings surprises that motivate analysts to reduce the average forecast error. The Accounting Review 83 (2): 303–26. Barth, M. E., R. Kasznik, and M. F. McNichols. 2001. Analyst coverage and intangible assets. Journal of Accounting Research 39 (1): 1–34. Berger, P. G., and R. Hann. 2003. The impact of SFAS 131 on information and monitoring. Journal of Accounting Research 41 (2): 163–223. Bhushan, R. 1989. Firm characteristics and analyst following. Journal of Accounting and Economics 11 (2–3): 255–74. Bhushan, R. 1994. An informational efficiency perspective on the post-earnings announcement drift. Journal of Accounting and Economics 18 (1): 45–65. Botosan, C. A., and M. Stanford. 2005. Managers’ motives to withhold segment disclosures and the effect of SFAS no. 131 on analysts’ information environment. The Accounting Review 80 (3): 751–71. Brown, L. D., and K.-J. Kim. 1993. The association between nonearnings disclosures by small firms and positive abnormal returns. The Accounting Review 68 (3): 668–80. Brown, L. D., A. C. Call, M. B. Clement, and N. Y. Sharp. 2015. Inside the “black box” of sell-side financial analysis. Journal of Accounting Research 53 (1): 1–47. Byard, D., Y. Li, and Y. Yu. 2011. The effect of mandatory IFRS adoption on financial analysts’ information environment. Journal of Accounting Research 49 (1): 69–96. Chen, S., M. L. DeFond, and C. W. Park. 2002. Voluntary disclosure of balance sheet information in quarterly earnings announcements. Journal of Accounting and Economics 33 (2): 229–51. Chen, X., Q. Cheng, and K. Lo. 2010. On the relationship between analyst reports and corporate disclosures: Exploring the roles of information discovery and interpretation. Journal of Accounting and Economics 49 (3): 206–26. Cheng, A., C-S. Liu, and T. Schaefer. 1997. The value-relevance of SFAS No. 95 cash flows from operations as assessed by security market effects. Accounting Horizons 11 (3): 1–15. Chuk, E. C., D. A. Matsumoto, and G. S. Miller. 2013. Assessing methods of identifying management forecasts: CIG vs. researcher collected. Journal of Accounting and Economics 55 (1): 23–42. Collins, D. W., S. P. Kothari, and J. D. Rayburn. 1987. Firm size and the information content of prices with respect to earnings. Journal of Accounting and Economics 9 (2): 111–38. Davis, A. K., J. M. Piger, and L. M. Sedor. 2012. Beyond the numbers: Measuring the information content of earnings press release language. Contemporary Accounting Research 29 (3): 845–68. Dechow, P. M., and I. D. Dichev. 2002. The quality of accruals and earnings: The role of accrual estimation error. The Accounting Review 77 (Supplement): 35–59. Dellavigna, S., and J. M. Pollet. 2009. Investor inattention and Friday earnings announcements. Journal of Finance 64 (2): 709–49. Demski, J. S., and G. A. Feltham. 1994. Market response to financial reporting. Journal of Financial Economics 17 (1–2): 3–40. Dhaliwal, D. S., S. X. Huang, I. K. Khurana, and R. Pereira. 2014. Product market competition and conditional conservatism. Review of Accounting Studies 19 (4): 1309–45. CAR Vol. 34 No. 1 (Spring 2017) 372 Contemporary Accounting Research D’Souza, J. M., K. Ramesh, and M. Shen. 2010. Disclosure of GAAP line items in earnings announcements. Review of Accounting Studies 15 (1): 179–219. Duru, A., and D. M. Reeb. 2002. International diversification and analysts’ forecast accuracy and bias. The Accounting Review 77 (2): 415–33. Francis, J., K. Schipper, and L. Vincent. 2002. Expanding disclosures and the increased usefulness of earnings announcements. The Accounting Review 77 (3): 515–46. Francis, J., K. Schipper, and L. Vincent. 2002. Earnings announcements and competing information. Journal of Accounting and Economics 33 (3): 313–42. Francis, J., R. LaFond, P. M. Olsson, and K. Schipper. 2004. Cost of equity and earnings attributes. The Accounting Review 79 (4): 967–1010. Francis, J., D. Nanda, and P. M. Olsson. 2008. Voluntary disclosure, earnings quality, and cost of capital. Journal of Accounting Research 46 (1): 53–99. Frankel, R. M., S. P. Kothari, and J. P. Weber. 2006. Determinants of the informativeness of analysts’ research. Journal of Accounting and Economics 41 (1–2): 29–54. Freeman, R. N. 1987. The association between accounting earnings and security returns for large and small firms. Journal of Accounting and Economics 9 (2): 195–228. Harris, M., and A. Raviv. 1993. Differences in opinion make a horse race. Review of Financial Studies 6 (3): 473–506. Heckman, J. J. 1979. Sample selection bias as a specification error. Econometrica 47 (1): 153–61. Hoberg, G. T., and G. M. Phillips. 2010. Product market synergies and competition in mergers and acquisitions: A text-based analysis. Review of Financial Studies 23 (10): 3373–811. Hollander, S., M. Plonk, and E. M. Roelofsen. 2010. Does silence speak? An empirical analysis of disclosure choices during conference calls. Journal of Accounting Research 48 (3): 531–63. Hoskin, R. E., J. S. Hughes, and W. E. Ricks. 1986. Evidence on the incremental information content of additional firm disclosures made concurrent with earnings. Journal of Accounting Research 24 (Supplement): 1–32. Hutton, A. P., and P. C. Stocken. 2009. Prior forecasting accuracy and investor reaction to management earnings forecasts. Working paper, Boston College. Indjejikian, R. J. 1991. The impact of costly information interpretation on firm disclosure decisions. Journal of Accounting Research 29 (2): 277–301. Ivkovic, Z., and N. Jegadeesh. 2004. The timing and value of forecast and recommendation revisions. Journal of Financial Economics 73 (3): 433–63. Kane, A., Y. K. Lee, and A. Marcus. 1984. Earnings and dividend announcements: Is there a corroborative effect? The Journal of Finance 39 (4): 1091–9. Kerstein, J., and D. Kim. 1995. The incremental information content of capital expenditures. The Accounting Review 70 (3): 513–26. Kim, O., and R. E. Verrecchia. 1991. Trading volume and price reactions to public announcements. Journal of Accounting Research 29 (2): 302–21. Kim, O., and R. E. Verrecchia. 1994. Market liquidity and volume around earnings announcements. Journal of Accounting and Economics 17 (1–2): 41–67. Kolev, K., C. A. Marquardt, and S. E. McVay. 2008. SEC scrutiny and the evolution of non-GAAP earnings numbers. The Accounting Review 83 (1): 157–84. Lang, M. H., and R. J. Lundholm. 1993. Cross-sectional determinants of analyst ratings of corporate disclosures. Journal of Accounting Research 31 (2): 246–71. Lang, M. H., and R. J. Lundholm. 1996. Corporate disclosure policy and analyst behavior. The Accounting Review 71 (4): 467–92. Lev, B., and S. R. Thiagarajan. 1993. Fundamental information analysis. Journal of Accounting Research 31 (2): 190–215. Li, E. X., K. Ramesh, M. Shen, and J. S. Wu. 2015. Do analyst stock recommendations piggyback on recent corporate news? An analysis of regular-hour and after-hours revisions. Journal of Accounting Research 53 (4): 821–61. CAR Vol. 34 No. 1 (Spring 2017) Disclosures and Analysts’ Information 373 Livnat, J., and P. A. Zarowin. 1990. The incremental information content of cash-flow components. Journal of Accounting and Economic 13 (1): 25–46. Matsumoto, D. A., M. Pronk, and E. M. Roelofsen. 2011. What makes conference calls useful? The information content of managers’ presentations and analysts’ discussion sessions. The Accounting Review 86 (4): 1383–414. Mayew, W. J. 2008. Evidence of management discrimination among analysts during conference calls. Journal of Accounting Research 46 (3): 627–59. Mayew, W. J., N. Y. Sharp, and M. Venkatachalam. 2012. Using earnings conference calls to identify analysts with superior private information. Review of Accounting Studies 18 (2): 386–413. McNichols, M. F. 2002. Discussion of “the quality of accruals and earnings: The role of accrual estimation error”. The Accounting Review 77 (Supplement): 61–9. Miller, G. S. 2002. Earnings performance and discretionary disclosure. Journal of Accounting Research 40 (1): 173–204. Ou, J. A., and S. H. Penman. 1989a. Accounting measurement, price-earnings ratio, and the information content of security prices. Journal of Accounting Research 27 (3): 111–44. Ou, J. A., and S. H. Penman. 1989b. Financial statement analysis and the prediction of stock returns. Journal of Accounting and Economics 11 (4): 295–329. Palepu, K., and P. Healy. 2008. Business analysis and valuation using financial statements, 4th edn. Cincinnati, OH: South-Western. Payne, J. L., and W. B. Thomas. 2003. The implications of using stock-split adjusted I/B/E/S data in empirical research. The Accounting Review 78 (4): 1049–69. Penman, S. H. 2010. Financial statement analysis and security valuation, 4th edn. New York: McGraw-Hill. Piotroski, J. D. 2000. Value investing: The use of historical financial statement information to separate winners from losers. Journal of Accounting Research 38 (Supplement): 1–41. Previts, G. J., R. J. Bricker, T. R. Robinson, and S. J. Young. 1994. A content analysis of sell-side financial analyst company reports. Accounting Horizons 8 (2): 55–70. Rogers, J. L., and A. Van Buskirk. 2013. Bundled forecasts in empirical accounting research. Journal of Accounting Economics 55 (1): 43–65. Shores, D. 1990. The association between interim earnings and security returns surrounding earnings announcements. Journal of Accounting Research 28 (1): 164–81. Song, W. L. 2004. Competition and coalition among underwriters: The decision to join a syndicate. The Journal of Finance 59 (5): 2421–44. Stickel, S. E. 1989. The timing of and incentives for annual earnings forecasts near interim earnings announcements. Journal of Accounting and Economics 11 (1–2): 275–92. Swaminathan, S. 1990. The impact of SEC-mandated segment data on price variability and divergence of beliefs. The Accounting Review 66 (1): 23–41. Tasker, S. C. 1998. Bridging the information gap: Quarterly conference calls as a medium for voluntary disclosure. Review of Accounting Studies 3 (1–2): 137–67. Wasley, C. E., and J. S. Wu. 2006. Why do managers voluntarily issue cash flow forecasts? Journal of Accounting Research 44 (2): 389–429. Watts, R. L. 1973. The information content of dividends. The Journal of Business 46 (2): 191–211. Zhang, Y. 2008. Analyst responsiveness and the post-earnings-announcement drift. Journal of Accounting and Economics 46 (1): 201–15. SUPPORTING INFORMATION Additional Supporting Information may be found in the online version of this article: Appendix S1: Creation of Unique Word/Phrase Lists for Each Financial Disclosure CAR Vol. 34 No. 1 (Spring 2017)