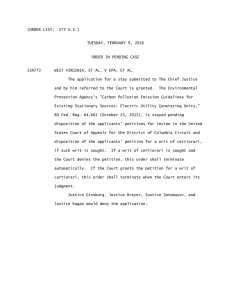

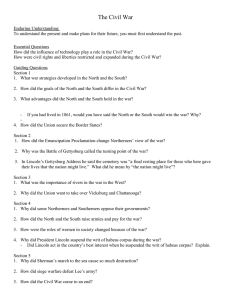

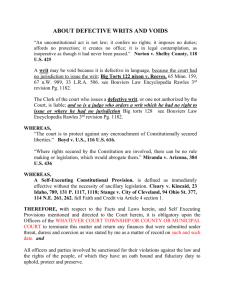

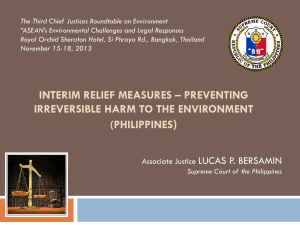

Legal Case Analysis: Certiorari, Amparo, Habeas Data, Custody

advertisement