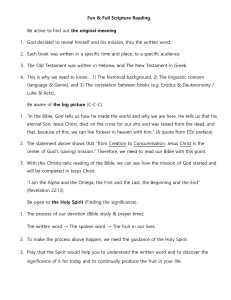

C H R I S T I A N I T Y T O D AY S P E C I A L I S S U E P. 8 HOW MAJORITY-WORLD CHRISTIANS ARE REMAKING MISSIONS ACROSS THE GLOBE IN PRISON NORINE BRUNSON ON ENDURING PERSECUTION P. 24 ON CAMPUS PARTNERING WITH THE HOLY SPIRIT P. 18 how women are rethinking global gospel proclamation _W19_Cover.indd 1 P. 30 HOW TO LIVE THE GOSPEL IN SUBURBIA HOME LOCAL COFFEE SHOP FRESH LANGUAGE FOR EVANGELISM P. 48 7/17/19 10:08 AM contents 8 CHRISTIANITY TODAY SPECIAL ISSUE: Your Mission Field Copyright © 2019 Christianity Today All rights reserved. Published by Christianity Today 465 Gundersen Drive Carol Stream, IL 60188 CHRISTIANITYTODAY.COM Printed in the U.S.A. Unless otherwise indicated, Scriptures are from the Holy Bible, NEW INTERNATIONAL VERSION®, NIV® Copyright © 1973, 1978, 1984, 2011 by Biblica, Inc.® Used by permission. All rights reserved worldwide. Scripture quotations marked (ESV) are from the ESV® Bible (The Holy Bible, English Standard Version®), copyright © 2001 by Crossway, a publishing ministry of Good News Publishers. Used by permission. All rights reserved. Scripture quotations marked (NASB) are from the New American Standard Bible® (NASB), Copyright © 1960, 1962, 1963, 1968, 1971, 1972, 1973, 1975, 1977, 1995 by The Lockman Foundation Used by permission. www.Lockman.org EDITOR IN CHIEF: Mark Galli PUBLISHER: Jacob Walsh EDITORIAL DIRECTOR: Ted Olsen CREATIVE DIRECTOR: Alecia Sharp PROJECT EDITOR: Kelli B. Trujillo ART DIRECTOR: Sarah Gordon DESIGN ASSISTANT/ILLUSTRATOR: Mallory Rentsch COPY EDITOR: Jenna DeWitt MARKETING: Leanne Snavely, Katie Bracy ADVERTISING: Walter Hegel PRODUCTION: Cindy Cronk WHAT MAJORITY-WORLD MISSIONS REALLY LOOKS LIKE With boldness and a pioneering spirit, Christians from the Global South are invigorating international missions. DORCAS CHENG-TOZUN 18 GO AND MAKE DISCIPLES. BUT FIRST, STOP. The crucial first step of ministry begins with the Holy Spirit. NOEMI VEGA QUIÑONES 24 HOW TO PRAY WHEN YOUR HUSBAND IS IMPRISONED Norine Brunson describes the faith practices that sustained her during persecution. INTERVIEW BY SEANA SCOTT 30 JUDEA, SUBURBIA, TO THE ENDS OF THE EARTH How to live the gospel in suburban America. ASHLEY HALES 36 ARE MISSIONARY KIDS MISSIONARIES? Families in the field say it’s complicated. RACHEL JONES 44 MY ROAD TO EMMAUS RAN THROUGH EAST L.A. Suffering and ministry turmoil left me devastated. Jesus met me there. TERESA KU-BORDEN 48 RETHINKING HOW WE TALK ABOUT SALVATION Paul’s favorite description is a phrase we rarely use. JULIE CANLIS 54 THE MOST DIVERSE MOVEMENT IN HISTORY Christianity has been a multicultural, multiracial, multiethnic movement since its inception. REBECCA MCLAUGHLIN 60 8 BOOKS TO EXPAND YOUR VISION FOR MISSIONS Reading recommendations for a ministry-oriented life. COMPILED BY KELLI B. TRUJILLO 66 UNBURDENING EVANGELISM How the Parable of the Sower frees us from a results-driven world. SHARON HODDE MILLER 3 FOB P3.indd 3 7/30/19 8:41 AM W editor’s note When Jesus died on the cross, only a small band of his followers, mostly women, were there to bear witness as humanity’s sins were atoned for. When he rose victorious over sin and death, again it was a small group of women who first witnessed the empty tomb, and it was Mary Magdalene whom he first commissioned to proclaim his resurrection. For the next 40 days, Jesus made quiet appearances among his friends and disciples. And then he left, ascending to the Father, leaving to them the task of proclaiming the gospel. Why didn’t Jesus announce himself with trumpets, proclaiming the salvation he offers in a display of glory, for all to see? Why, instead, did he commission flawed and limited humans to “make disciples of all nations”? It’s a confounding and holy mystery that God chose them—and he chose us—to build his church. Until the future day when, indeed, “the trump shall resound and the Lord shall descend,” we are to be his witnesses, empowered by the Holy Spirit, trumpeting the announcement of the kingdom. God left this task to us—to us humans who, full of good intentions, are also full of inclinations toward sin, often tripping our way through our kingdom proclamation. Yet in our weaknesses, limitations, and failures, we are proclaiming something essential: that the gospel is for sinners—that grace is a (necessary) reality both for the hearers and the proclaimers of the message. This CT special issue explores several of these important themes—human struggles and limitations (p. 44), the empowering work of the Holy Spirit (p. 18), what missional living looks like in international contexts (p. 8) and in America (p. 30), as well as fresh ways to think about evangelism (p. 48 and p. 66). In this issue we spotlight, in particular, the work of ordinary women as leaders, pioneers, and faithful proclaimers of the kingdom. At the church I attended as a teenager, these words were emblazoned above the main exit doors: “You are now entering your mission field.” Every Sunday, as we’d file out of church back into our normal lives, we read the needful reminder that we are each missionaries. It’s a reminder I still need today: that the great, global commission given to Jesus’ early band of followers was never just for vocational missionaries. It is for me and for you. Whether one serves abroad or lives right here—wherever “here” is as you read these words—we are each living in the mission field to which God has called us. Go, therefore, and make disciples. KELLI B. TRUJILLO Editor 5 Ed Note P5.indd 5 7/29/19 8:29 AM WITH BOLDNESS AND A PIONEERING SPIRIT, CHRISTIANS FROM THE GLOBAL SOUTH ARE INVIGORATING INTERNATIONAL MISSIONS. DORCAS CHENG-TOZUN ILLUSTRATION BY MAGGIE CHIANG 8 Cheng Tozun P8.indd 8 7/17/19 10:17 AM understand that they are worthy before God. They are valued regardless of economic or social status, or skin color.” B Beauty Ndoro and her husband had been living among and serving the residents of slums outside Harare, the capital city of their native Zimbabwe, when they unexpectedly received a letter from Los Angeles–based missions organization Servant Partners. The letter said Servant Partners felt led to recruit Africans to serve in Mexico. They had gone online to search for like-minded ministers in Africa—and came across Ndoro and her husband. The couple had considered serving in another southern African country. Ndoro’s husband felt a burden for Tibet. But Mexico? That had never crossed their minds. They ignored the letter. Servant Partners persisted, sending two more letters over the next six months. Lisa Engdahl, co-general director of Servant Partners, says they typically search far and wide for missionaries willing to serve in the world’s poorest communities. “We are always trying to recruit a breadth of people because of the demands of our work,” she told me. “Our teams have looked to diversify as much as possible.” The recruitment of Ndoro and her husband was a recognition that “there are many strong, godly leaders in the African church whom God is calling into cross-cultural ministry.” “I wasn’t sure if God wanted me to move so far from family, to go to a different culture,” Ndoro told me. “I didn’t know any Spanish, and my daughter was only two years old.” But then she started receiving confirmation from others. “I hear ‘Mexico’ and God’s calling upon your life,” they told her. Eventually, it became clear that Mexico was where God intended them to go. “I had my own fears, but I was so excited,” Ndoro said. “I knew God was going to be with us.” That was ten years ago. Since then, Ndoro and her family have served in both Mexico and Nicaragua, living in urban slums and leading Bible studies and recovery groups for survivors of trauma. Several of these Bible studies have grown into new churches. While there have been challenges, Ndoro has no doubt that Latin America is exactly where God wants her, a black Zimbabwean woman, to be. “Because of knowing who I am in Christ and as an African, that has helped me help others 10 A NEW WAVE OF MISSIONARIES Beauty Ndoro is part of a growing movement of international missionaries sent out from the Global South, which includes Africa, Asia, Latin America, and the Caribbean. According to Christianity in Its Global Context, 1970–2020, a report by The Center for the Study of Global Christianity at Gordon-Conwell Theological Seminary, 66 percent of all Christians will be from the Global South by 2020, up from 43 percent in 1970. This could reach 75 percent by 2050. Christianity is surging in these regions, even as North America and Western Europe see the number of religiously unaffiliated growing at an increasingly rapid pace. As the demographic center of the global church shifts, so too does fervor for international missions. As Christianity Today has previously reported, the beginning of this century has marked a dramatic swing from the model of Western missionaries going out to the rest of the world to “the sending of international missionaries to all of the world’s countries from almost every country,” according to Christianity in Its Global Context. The World Christian Database reports that while the US still sends out the most missionaries, that number is decreasing. There were 121,000 active American missionaries in 2015 (the most recent year for which data is available), down from 127,000 in 2010. During that same period, the number of missionaries from non-Western countries increased significantly. Brazil, for example, went from 34,000 to 35,000 missionaries, and South Korea leaped from 20,000 to 30,000 missionaries. Missionary movements from the Global South aren’t entirely new. For example, the Back to Jerusalem C H R I S T I A N I T Y T O D AY. C O M / W O M E N Cheng Tozun P8.indd 10 7/17/19 10:23 AM movement—an effort by Chinese Christians to evangelize all the Buddhist, Hindu, and Muslim people groups who live along the old Silk Road—traces its roots back to the 1920s. It was newly revitalized in 2003 by exiled house church leader Liu Zhenying (also known as Brother Yun). South Korean missionaries have been going to the US since the 1970s to “‘bring the gospel back’ to Americans, particularly white Americans,” reports sociologist Rebecca Y. Kim in The Spirit Moves West: Korean Missionaries in America. The Filipino Sending Council, affiliated with US-based SEND International, has been sending missionaries abroad for more than 30 years. This is the first time, however, that the world has seen so many missionaries from Asia, Africa, and Latin America crossing national borders, including going to the homelands of the missionaries who first brought them the gospel. In 2015, 9 of the top 20 sending countries—including Brazil, the Philippines, China, India, Nigeria, and South Africa—were in the majority world (also referred to as the developing world), with a total of 101,000 international missionaries. These missionaries come in all forms—tentmakers and donor supported, organization affiliated and free agents, evangelists and church planters and incarnational ministers—but they each bring unique strengths and a vibrant faith. PHOTO COURTESY OF SERVANT PARTNERS THE INTERCONNECTED BODY Globalization has tied the world’s economies together, but it has also facilitated international missions through increased migration, economic mobility, and information access. The United Nations reports that the number of international migrants is growing rapidly each year, with 258 million recorded in 2017. (Only 10 percent of these were refugees and asylum seekers.) Today, more than 4.34 billion people in the world, or 56.8 percent of the global population, have internet access, up significantly from 3.18 billion in 2015. News and information, including news about the global church, can reach nearly every corner of the world. “What do you mean churches are shutting down? They’re becoming more secular? Less young people are in the church?” Zimbabwean Tatenda Chikwekwe recalls thinking as his home church in Harare heard about Christianity’s decline in North America and Europe. “To see nations with such strong Christian heritage, rich church Beauty Ndoro, from Zimbabwe, working in Managua, Nicaragua. history, to see the recession in that—my heart was being broken constantly,” he told me. After being sent out in 2002 and participating in various ministries around East Africa, Chikwekwe joined the pastoral staff at Nairobi Chapel, a nondenominational church in Kenya. There, the leadership was engaged in an intentional conversation about the role of the African church in global missions. They studied the teachings of 1 Corinthians 12, about the roles of different members of the body of Christ, from a global perspective—and concluded that Africa, as an essential member of the global church, needed to do more. Faith Mugera, pastor of global partnerships at Nairobi Chapel, is one of the key leaders of the resulting missions efforts. “For a long time, we felt like the Great Commission was a mandate given to the Western world,” she explained. “But do we believe that we are part of the global body of Christ? If so, then we absolutely cannot dismiss ourselves from that. If we as the African church are not functioning right, then the global body is missing out.” 11 Cheng Tozun P8.indd 11 7/29/19 8:30 AM Nairobi Chapel is at the leading edge of an increasingly strategic approach to missions among Global South Christians. At the turn of the century, Chikwekwe and other missionaries like him were often sent out with few resources, minimal connections, and no plan aside from sharing the gospel wherever they could. Now more churches and ministries are borrowing from their Western counterparts and placing a heavier emphasis on goal setting, training, and strategic partnerships. Mugera and her colleagues, for example, have set the audacious goal of planting 300 churches worldwide, with 20 of those in capital cities across Africa and 10 in international cities of influence. To support this goal, they train three separate cohorts of young leaders each year in leadership and spiritual development, as well as life skills like resourcefulness and relationship building. Nairobi Chapel has already sent ministers and church planters to Chicago, London, Sydney, and Christchurch. Their next mission field: San Francisco, which they have spent the last year praying and fasting for. MISSIONS OUTSIDE OF TRADITIONAL MODELS That doesn’t mean that Global South organizations like Nairobi Chapel are approaching missions in the same way as North Americans and Europeans. “Previous models don’t work in our context,” Mugera said. In those missions models, “you have to be in school for a long time. You have to raise a lot of financial support. You need a missions agency.” But these resources aren’t readily available for most Africans. “We don’t have finances. We don’t have the same visa access. We don’t have easy access to education.” These challenges have forced Nairobi Chapel and other churches and missions organizations to think creatively about how to send out missionaries, often relying on multinational collaborations and alternative visa options. Outside of Africa, Nairobi Chapel relies on existing local churches to invite their ministers, sponsor their visas, provide homes, and raise financial support for their expenses. Other ministries are capitalizing on an increasingly global economy and job market. Since 2015, the government of China has committed to investing $120 billion in Africa, enabling hundreds of thousands of Chinese workers and entrepreneurs to move to the continent to seek economic opportunity. One Hong Kong–based couple I spoke with is targeting Chinese businesspeople migrating to Africa and elsewhere, challenging the Christians among them to also be evangelists. In the Philippines, missions groups are training some of the more than 2 million Filipinos who work abroad as everything from engineers to domestic helpers, equipping them as tent-making 12 MOST MISSIONARIES SENT US Brazil South Korea Philippines UK China India Nigeria South Africa Mexico Colombia Netherlands Bolivia = Majority world country 10K 30K 120K MOST MISSIONARIES SENT PER MILLION CHURCH MEMBERS South Korea Somalia Singapore US Netherlands Morocco Hong Kong UK Japan Taiwan 0 2,000 TOTAL CHURCH MEMBER POPULATION South Korea Somalia Singapore US Netherlands Morocco Hong Kong UK Japan Taiwan > 40 0 40 MILLION Included countries have a population of 5 million or higher. SOURCE: WORLD CHRISTIAN DATABASE, 2015 C H R I S T I A N I T Y T O D AY. C O M / W O M E N Cheng Tozun P8.indd 12 7/17/19 10:58 AM missionaries who can witness to their employers, colleagues, and neighbors. FACING UNIQUE RISKS For these missionaries, simply applying for a visa to a country that does not welcome migrants who look like them can be an act of faith. Some majority-world missionaries experience prejudice and hostility in the countries they have come to serve. Melody Mweu, a Kenyan missionary who served in Khartoum, Sudan, told me she initially had trouble being accepted by the upper-class Sudanese women she encountered. In that context, she explained, “the darker you are, the lesser you are.” Though Melody eventually befriended a group of Sudanese women, she still had to be careful about where they met, knowing that she would not be welcome in certain locations. Beauty Ndoro similarly recalls needing quite a bit of time to gain the trust of her Nicaraguan neighbors in the slums. “When we started walking in our community, people were afraid. They didn’t want to talk to us,” she remembered. But she and her husband kept showing up, talking to people and praying for them. This eventually led to the start of a women’s ministry. These racial tensions can have real consequences. Hondurans Jairo and Lourdes Sarmiento have been leading a church plant in a low-income Latino community in California for several years. Today, as the highly charged debate about Latin American immigrants and asylum seekers roils American politics, the Sarmientos’ own immigration status remains in limbo. SPIRITUAL GRIT, FRESH PASSION Enduring such hardships requires significant faith and perseverance, which many in the Global South have in abundance. This spiritual grit has often been shaped by decades of poverty, war, colonization, and political instability. “Growing up in poverty, being not as privileged, has given us a sense that we can do so much with very little,” Chikwekwe told me. Among the missionaries I interviewed, almost all of them shared stories of childhood hunger, abuse, neglect, or persecution. Two women had been nearly sexually assaulted in their home countries, and another was almost raped while on the mission field, but they were miraculously protected. “There’s a passion about our faith that has been refined by seeing God at work in our most difficult circumstances,” reflected Mugera. Even in South Korea, today one of the most industrialized nations in the world, memories of war and its hardships continue to influence how missionaries approach their work. Lydia Park (a pseudonym), a native of Seoul who has served in Libya and Zambia and now Kenya, says the Japanese occupation of Korea from 1910 to 1945— and Koreans’ decades-long resistance against it—seeded a determined mindset among modern Korean missionaries. “If Koreans believe something is very important, we are willing to give ourselves, to give our lives,” Park told me. “We never stop, never give up.” The passion and commitment of missionaries from the Global South are also fueled by fairly recent encounters with God. The church is rapidly growing in this part of the world, populated by many new believers. The number of Christians across Africa has grown from 360 million in 2000 to nearly 619 million in 2019, according to the Center for the Study of Global Christianity. In Asia, Christianity is growing at twice the rate of the population, due mostly to new converts. Aarthi Jambhulka, who evangelizes and preaches in countries as varied as Nigeria, Myanmar, Australia, and Canada, says she rarely encounters others from her native India who come from multigenerational Christian families. Her parents began following Jesus shortly after she was born, and she faced significant persecution for her faith while growing up. Unlike many Americans or Europeans who have “inherited” their faith, Jambhulka explains that “our experiences are very fresh. It’s what we’ve experienced directly. It’s not something that’s been handed down to us. It’s very real.” CONFIDENCE AND CULTURAL UNDERSTANDING This sense of the immediacy of God is one of the most powerful gifts that missionaries from the Global South have to share, according to Engdahl of Servant Partners. “They have an expectation of the movement of God because the 13 Cheng Tozun P8.indd 13 7/17/19 10:58 AM church is flourishing in their home countries,” she told me. “They enter with faith for the movement of God.” They also enter this work with important cultural commonalities that facilitate their ministry. Singaporean Jemima Ooi has been a full-time missionary in Africa for seven years and currently serves in the war-torn Democratic Republic of Congo. In her experience, it’s not uncommon for Congolese to approach her and say, “Asians and Africans, we are brothers and sisters.” “Some cultural elements come more intuitively to me: honor elders, speak to the hearts of people, be concerned with someone’s entire family and not just their work,” Ooi told me. She cites the fact that 75 percent of the world’s “There’s a passion about our faith that has been refined by seeing God at work in our most difficult circumstances.” FAITH MUGERA population comes from honor-shame cultures and collectivistic mindsets—which, notably, does not include Americans, Canadians, or Western Europeans. Growing up with a similar worldview makes it easier for missionaries like Ooi to operate with cultural sensitivity in new countries. Her understanding of how to honor the Congolese has even helped to keep her safe in one of the world’s worst conflict zones. “They feel that you’re a kindred spirit,” Ooi explained. “They take care of [my colleagues and me] when there are raids.” Even the obvious differences between Global South missionaries and those in their adopted countries can be leveraged for the kingdom. Several missionaries I interviewed told me how they were curiosities when they first began serving, prompting regular inquiries of “Why are you here?” that opened the door for deeper conversations. “It’s important for people to know the gospel is not just for white people or Westerners,” Edith Law (a pseudonym), a 14 missionary from Hong Kong, told me. “The gospel is related to them, not just the Western world.” BRINGING DIFFERENCES TOGETHER FOR THE KINGDOM Missions organizations in the West are taking notice of this spiritual awakening in Africa, Asia, and Latin America and are taking intentional steps to bolster their missionary efforts. SEND International, for example, is one of a growing number of missions agencies actively recruiting missionaries from the Global South. Currently about 20 percent of their 500-plus ministry workers are not from the US, Canada, or Western Europe; recently, they set the goal to increase this to 50 percent by 2029. “This is the current of God’s work that’s flowing in the world, and we want to be a part of that,” Barry Rempel, SEND’s globalization office director, told me. He sees this kind of multicultural, multinational collaboration as essential to the vitality and growth of the future church. “The main advantage is that it gives us a more full-orbed picture of Christ’s body, a more fullorbed expression of his work. Each place, wherever it is, brings a further expression of Christ’s body into our organization, represents Christ in a more glorifying way, and leads to more fruitfulness.” Faith Mugera agrees. “There is liberty in difference. God allows our differences to come together in the good of what we’re desiring to do.” And when every member of the global body of Christ recognizes their unique gifts and callings and brings those to bear for the sake of the kingdom, “nothing is impossible,” Mugera said. “We know for sure that there will be revival.” DORCAS CHENG-TOZUN is the author of Start, Love, Repeat. She has lived in mainland China, Hong Kong, and Kenya. C H R I S T I A N I T Y T O D AY. C O M / W O M E N Cheng Tozun P8.indd 14 7/17/19 10:58 AM THE CRUCIAL FIRST STEP OF MINISTRY BEGINS WITH THE HOLY SPIRIT. NOEMI VEGA QUIÑONES 18 C H R I S T I A N I T Y T O D AY. C O M / W O M E N Vega Quinones P18.indd 18 7/17/19 1:29 PM SOURCE PHOTO BY ALI YAHYA / UNSPLASH T Twelve years ago, I was an energetic campus minister leading outreach to college students at Fresno State. I longed to see their lives transformed by Jesus the way that he’d transformed mine. But in my eagerness, I pushed one particular student to explore her faith in connection with her ethnic identity as a Mexican American. When she said she wasn’t interested in growing in that area, I misinterpreted it as a lack of teachability rather than as a “not now” from the Holy Spirit. Eventually, trust was broken and she left the fellowship to join another ministry. I was heartbroken. Where had I gone wrong? Years later, I became the Latino student outreach coordinator for central California and Las Vegas. In that season, wise Latino mentors coached me to grow in listening to the Lord. They encouraged me to take time to pray with students and listen to the Lord’s yearning for their lives. This time, I began to approach ministry differently. I listened and waited on the Holy Spirit for strategy and vision. By the end of three years, we had reached over 100 Latino students in our ministry. How often do we minister out of our own insights or impulses rather than relying on the Holy Spirit’s guidance, however long it takes to discern? Waiting is countercultural; it’s antithetical to the pace of our daily lives. The technological age we live in values efficiency and urgency. As a culture, we abhor waiting. Our world is not designed to help us stop and reflect on the presence of God at any given moment. Listening and waiting, thus, are disciplines we must exercise regularly—especially when it comes to partnering with the Holy Spirit. I’ve learned—and I’m still learning—that listening to the Holy Spirit is the first step in ministry. It is our first act of love. LISTENING TO OUR GUIDE The Holy Spirit is not an “it” or a distant force. The Holy Spirit is a person, the third member of the Holy Trinity. “Spirit” is the name of the divine person Jesus promised would come to believers after he ascended (John 14:15–17). “Spirit” is the name of the divine person who hovered over the waters during Creation (Gen. 1:2). The Holy Spirit was 19 Vega Quinones P18.indd 19 7/17/19 1:29 PM present from the very beginning and even to the very end of the age (Matt. 28:20). The Holy Spirit has many other names in Scripture, including advocate, counselor, breath, wind, life, and Spirit of Truth. While various Christian traditions understand the embodied gifts of the Spirit in different ways, Paul is clear that in the different gifts and Spirit-led ministries of God’s people, “in everyone it is the same God at work” (1 Cor. 12:6). The Holy Spirit gives every Christian believer the gift of partnership with God. Just as Jesus is described as a friend to believers, the Holy Spirit can be described as a helpful guide. We can rest assured that when we listen, this person of the Trinity is present with us—whispering, speaking, sharing, guiding, and loving. WAITING WITH HOPE When I moved to minister in San Antonio, where I now serve, my new staff team and I spent our first seven months listening to the Lord and waiting on his vision for our area. At first, this waiting felt restless and heavy. Worry tried to creep in and internal pressure to come up with a captivating vision statement was mounting. But eventually my posture shifted toward waiting with hope instead of fear. In Spanish, the word for “wait” is espera and the word for “hope” is esperanza. Hope is embedded with waiting in faith. Waiting in hope cultivated a peace, trust, and dependence on the Lord that slowly emerged into a clear vision centered in love for God and his people. When we seek to partner with the Holy Spirit in mission, waiting in hope for the Spirit’s leading is essential. Two biblical examples of people who waited with hope to receive instruction from the Holy Spirit stand out to me: Anna and Elijah. Anna, in Luke 2:36–38, was an 84-year-old prophet of God waiting for the redemption of Israel. For many of those years she lived as a widow, worshiping and fasting day and night. When Anna saw Mary and Joseph in the Temple holding baby Jesus, she walked up to them and started praising God. She was able to recognize who Jesus was because she lived in the presence of God, her spirit connecting with his Spirit every single day as she prayed. She waited for years in hope. She waited with a focused vision of the redemption of Israel, birthed out of years of prayer and worship. While others misunderstood, Anna knew that redemption would not come from the false messiahs who attempted to overthrow their oppressors. Anna’s years of waiting, listening, and partnering with the Holy Spirit prepared her to recognize the Savior! The longer we partner with the Holy Spirit in mission, the easier it becomes to distinguish his truth from false narratives. 20 Elijah pressed into hope amid hardship. Consider the desperation Elijah felt after all the other prophets of Israel were slaughtered (1 Kings 19). Jezebel promised to kill Elijah, too, so he ran to save his life only to later ask the Lord to take his life. Twice during this time an angel ministered to Elijah and provided him with food and drink. Instead of continuing to run, Elijah chose to go to Mount Horeb, the same place where Moses had heard from the Lord. Perhaps in his desperation, Elijah remembered that Mount Horeb was a place of hope, a place where the Lord speaks. It took Elijah 40 days and 40 nights to get there. During the journey, I imagine he did a lot of thinking, arguing, listening, realizing, and speaking to God. By the time he arrived, Elijah had cultivated enough hope to hear the voice of Yahweh once again. The Lord asked In Spanish, the word for “wait” is espera and the word for “hope” is esperanza. Hope is embedded with waiting in faith. Elijah what he was doing there, then led Elijah through a series of events designed to teach him to listen intently (vv. 10–13). First, the wind came, then an earthquake and a fire, but the Lord was not in them. Elijah then experienced the presence of God through a C H R I S T I A N I T Y T O D AY. C O M / W O M E N Vega Quinones P18.indd 20 7/17/19 1:30 PM gentle whisper, a voice asking again, “What are you doing here, Elijah?” Notice that the Lord asked Elijah the same question twice (vv. 9 and 13), but it was only the second time, after the experience of listening, that the Lord gave further instruction to Elijah about his mission. Perhaps transformation happened in Elijah’s waiting on the presence of the Lord. Perhaps the Spirit of God was teaching Elijah discernment. God can manifest himself in powerful ways, as Elijah had seen in his own ministry, but perhaps it was time for Elijah to hear the voice of the Lord as a gentle whisper. Like Elijah, we may experience ministry failure, doubt our calling, or feel tempted to give up. But the Holy Spirit will never let us run so far that we are no longer in his presence. The gentle whisper of the Spirit is there—we can learn to listen and wait for it in hope. LEADING WITH LOVE Partnering with the Holy Spirit in ministry involves cultivating deep love for God and his people. Those of us who hope to present the gospel in our current cultural zeitgeist do well by noting the concerns that others have about missions and evangelism. While we have learned helpful ways of sharing our faith, some of our hearers may still be pained and even turned away from the gospel by the way Christianity has been presented in the past. The history of colonization is one to remember and learn from, lest we repeat some of the same mistakes. We must acknowledge and remember where evangelistic efforts begin to go wrong. Our Christian witness falls short when we abandon love as the center of our Great Commission. Love does not conquer others and does not lord power over others. Love does not consider oneself better than the other but rather sees the other as beloved by the Creator. The Holy Spirit helps us cultivate deep, godly love. This divine love is the natural fruit of the Spirit’s life within us. But if we aren’t partnering with the Spirit, we may be inadvertently ministering out of other motivations, such as a desire to be spiritually “successful” or a guilt-driven compulsion to work. Frustration, impatience, blaming others, or a lack of teachability and humility can all be indicators that God’s love is not at the center of our mission. Those who are on the receiving end of our ministry efforts immediately know when a person is authentically serving out of love or another type of motivation. People don’t want to be evangelism projects or the next target goal for outreach! People want to be known. People want to be loved. People want to be seen. People want to partner. Ministries that empower those they serve embody the ministry that Jesus modeled. Consider how Christ empowered the woman at the well to go and tell her testimony to her village (John 4). In partnership with the power of God, she shared her story and many people came to believe as a result. Partnership centered in love for God and his beloved is the most powerful, life-transforming, and lasting ministry model we have to offer. We are all called to the beautiful invitation of Matthew 28—to “go and make disciples of all nations”—and we are equipped with the powerful promise of Emmanuel, “I am with you always, to the very end of the age.” I said yes to Jesus because I wanted to be with him—I literally want to walk with him every day. I didn’t say yes so that I could lead a ministry. That is a residual blessing after the greatest gift: to be in the presence of the One who fully knows me and seeks after me. Jesus said to remain in his love (John 15:9). Out of this remaining—this abiding—we can follow his command to love one another because we have known and have experienced his love for us. Out of this love, people will know we are his followers (John 13:34–35). Spirit-fostered love is the key to our evangelism. Jesus promises us the Holy Spirit. We do not have to fight for the Holy Spirit to see us; we do not have to compete for the Spirit’s love. Like Anna, we can cultivate daily prayer rhythms to step away from the culture of urgency and efficiency and to step into relating with God’s Spirit in the present. Like Elijah learned, partnership with the Holy Spirit is cultivating a posture ready to listen to the Creator’s gentle whispers. Partnering with the Holy Spirit is an act of love. It is the first step of ministry. NOEMI VEGA QUIÑONES is the South Texas area ministry director for InterVarsity Christian Fellowship and is a co-author of Hermanas (InterVarsity Press). 21 Vega Quinones P18.indd 21 7/17/19 1:30 PM OFFICIALS ARRESTED ANDREW AND NORINE BRUNSON IN 2016 WHEN THEY APPLIED FOR PERMANENT VISAS IN TURKEY, WHERE THEY’D LIVED AND MINISTERED FOR 23 YEARS. AUTHORITIES RELEASED NORINE 13 DAYS LATER, BUT ANDREW REMAINED IN PRISON FOR TWO YEARS, ACCUSED OF BEING A SPY. PHOTO BY PATRICK ROBERTSON / COURTESY OF BAKER PUBLISHING Norine stayed in Turkey after her release, advocating for Andrew’s freedom and helping to lead the church they’d planted. Andrew’s forthcoming book, God’s Hostage (Baker, October 2019), details the Brunson’s story of imprisonment and perseverance. CT spoke with Norine about the spiritual habits that strengthened her during her years of ministry and that sustained her marriage and her faith during persecution. Your husband, Andrew, has said, “Norine was stronger than I was.” This strength came from a reservoir in your soul because of your daily time spent with God for years prior to the ordeal. What did that spiritual habit look like for you? Well, it’s looked different depending on the season of life. There’s no single prescription. But I always include time in prayer and the Scriptures. And when I read the Word, I try to align myself with it. Like when I read, “Arm yourself with the same attitude” as Christ, in his suffering, I say, “Yes, Lord. Let me have that.” I also make it a habit to write down answers to prayer, blessings, things I am thankful for. There were days during Andrew’s imprisonment where I would say, “Okay, Lord. I have prayed everything I know. Here I am again.” There is something about just sitting in the Lord’s presence. Just being. Does my mind wander when I spend time with the Lord? Absolutely. Do I check my phone? Often. That’s just the reality. But I’m persuaded that time with the Lord is essential. How can we have a relationship with God unless we spend time with God? It’s like putting reserves in your spirit. Then the Holy Spirit brings it up when it’s needed. Were there other spiritual habits that were significant in your relationship with God before you and Andrew were arrested? Andrew has always been a worshiper, and this carried into the church and has influenced me. Fasting is also a habit of our spiritual life—not all the time, but for specific situations in ministry or our family. One time several years ago, I fasted specifically regarding my fear of persecution. I was afraid of being tortured, to be honest. And I was saying, “Lord, prepare me for anything like this that I might face.” Not that there was any particular threat at that time—it has just been a fear of mine. Fear is something I have way too much of, and I know God wants to change that. During the two years Andrew was imprisoned, what did your spiritual life look like? How did you grow? I was so aware that I couldn’t do it alone. It was so hard to get out of bed in the morning. I’d sleep well, but then I’d wake and think, Oh. We’re still here. It was so hard to get out of bed. Very hard. Really hard. So I would put my hand up every day before I got out of bed and say, “Okay, Lord. I’m taking your hand. Walk through this day with me.” And then at some point it shifted. Not like, “Okay, God. I’m taking your hand. Walk through this day with me.” But me saying, “God, you lead this day. I’m with you.” I would submit every interaction, every thought, every emotion, every minute, and just really, really, thoroughly say, “Lord, you lead and hold me through this day, as well as Andrew and our kids. But you lead.” I think I grew in awareness of my dependence on God and also in willingness to let the Spirit lead me in my day instead of trying to control my schedule. 25 Scott P24.indd 25 7/29/19 8:31 AM You’re a mom of three. What was God teaching you as a parent during this time? You know, that was one of the hardest things. When I was first arrested, I didn’t know if we were going to get out. I said, “Okay, Lord. You have to take care of my kids.” Because all of a sudden, you are powerless. I couldn’t get any word to them or do anything. I was like, “This is way beyond me. Lord, You’re on. You have to do it.” Obviously, I should say I learned to trust more. Did I or did I not? I don’t know. I hope so. Were there challenges that surprised you as you continued to live and minister in Turkey during Andrew’s imprisonment? It was difficult and unexpected for sure, but not surprising. I didn’t know if I was going to be rearrested. I would hear voices coming up the stairs or in the hallway—and I wondered if they were coming to get me. Then the voices would continue past the floor or my door and I would feel relief. On one end it was great to know that my kids were safely in the States, but it was also hard to be away from them and to know they were having to walk through this without me and without each other, as they were all in different places. And then there were the things in daily life that Andrew would always take care of, like working the computer or making sensitive ministry decisions—and I had to do them without his help or advice. It was very difficult. I just did what I could and others helped. Did persecution impact your practices of evangelism and ministry? I don’t think anything changed. We’d never called ourselves “missionaries” because it’s a misunderstood word. But we always told the Turkish people who we are and what we do. We are Christians and we pray for people and share the gospel. That is who we are. Actually, the man who was leading the church— he and I were doing it together, but he carried the bulk of the work—really kept things going and, in fact, pressed forward. This could have been a time when we retreated, but for us in the church, it was time to keep going. While Andrew was imprisoned, authorities let you visit him for about 35 minutes a week. What did those visits look like? Every week, I’d write down what I wanted to tell 26 Scott P24.indd 26 Andrew. I’d include what I thought God wanted me to impart in prayer over him that week, things others sensed the Lord was showing, diplomatic news, whatever might encourage Andrew. And then I would memorize it the best I could before our visit. When I saw him, we put our hands on the glass and I prayed for him. I said something like, “I bless you in the name of the Lord. I speak life over you. I speak hope over you”—whatever the Lord led me Obviously, I should say I learned to trust more. Did I or did I not? I don’t know. I hope so. to say. I just tried to pray over him and bless him briefly. Then we started to talk. I told him as much good news as I could. Then he would tell me how he was doing. But we watched our words because the government listened to everything we said. Was there ever a time when you felt like you lacked that personal reservoir of strength to encourage him? Absolutely. There were many times I thought, God, I’m so discouraged. How can I go and encourage him? How on earth can I do it? But I’d still go in. And I started to go in deliberately. When I signed in and approached the gate, I lifted my head and said to myself, I’m the daughter of the King going in to see a son of the King. But I was also like, Lord, you back me up here. And oftentimes, the Lord gave me grace right when I was with him. What would you say to someone who is in a season of darkness or facing persecution? I recently listened to a Canadian couple who’d been imprisoned in China. I agree with what the wife said about facing difficulties or persecution: You have to go to God first. You don’t go to your Christian friends, your doctor, or your counselor first. Those things are all good, but you have to know to go to God first. And as you partner with him, you will be able to access his resources and make it through. C H R I S T I A N I T Y T O D AY. C O M / W O M E N 7/17/19 1:04 PM PHOTO BY BLAKE WHEELER / UNSPLASH judea, suburbia, to the ends of the earth HOW TO LIVE THE GOSPEL IN SUBURBAN AMERICA. ASHLEY HALES 30 Hales P30.indd 30 7/17/19 11:50 AM A PHOTO BY BLAKE WHEELER / UNSPLASH As a teenager, I’d thumb through the missions catalog. Each location for a short-term mission project felt a bit like hope. Hope for change. Hope for adventure. And most of all, hope that I was living a full Christian life. In my evangelical youth group, the pinnacle of leadership and belonging came through missions—missions to Mexico or a mission trip to Europe. Missionaries were serious about God. In those days, it seemed to me these career paths were just a matter of a simple equation: If you loved Jesus and took your faith seriously, then you’d choose to move overseas as a missionary or at least work in full-time vocational ministry here. But now, most of us in America live rather ordinary lives in the suburbs. Our days are more often filled with driving children to soccer in our minivans than sharing the gospel with unbelievers. Rather than building houses for the poor, we join the PTA. We go to church and wonder—maybe when we hear a missionary speak—if we somehow missed our calling. If we’re not in full-time vocational ministry, if we’re not missionaries, or if we’re not a key leader in our local congregation, how do we connect the dots between what we say we believe and the lives we live? If we’re not doing “big things” for God, is there a way to live gospelcentered, outward-focused lives in the suburbs? The suburbs aren’t a second-rate mission field. They are, for many of us, the place to which we’ve been called, the place we are to love and serve, and a place where we can live as missionaries right in small spaces of our ordinary lives in our cul-de-sacs. Suburbia is a strategic mission field. THE SUBURBS ARE CHANGING Contrary to the stereotype of the suburbs as icons of homogeneity—and historical efforts to create and keep them that way—today’s suburbs are telling a different story: They are now marked by growing racial and ethnic diversity—and even socioeconomic diversity. No longer is the suburb’s only narrative that of rich, white men commuting out of 31 Hales P30.indd 31 7/17/19 11:49 AM suburbia into large cities for work. Instead, as Kenneth T. Jackson has observed, “suburbs have become like cities, and cities like suburbs.” Pew Research Center reports that, since 2000, the suburbs are growing more than urban or rural environments in terms of birth rate, receiving former urban and rural dwellers, and immigrants from abroad. If, according to the American Housing Survey, more of America is suburban than not, and if the suburbs are growing in all forms of diversity, then we cannot simply denigrate the suburbs as monolithic in terms of race, class, and socioeconomic status, nor ought we write them off as culturally dull. Since suburbs are actually more politically diverse than cities and rural areas, these communities are also poised to be places where we begin to model conversation and reconciliation rather than retreating to our ideological bunkers. Suburbs today are a strategic place for gospel witness. Evangelism and discipleship in suburbia often happen in ordinary ways. In our suburban congregation in Southern California, I see it in the purposeful conversations a Christian hairdresser has with her clients, some of whom have since visited our church with their families. Another family I know is intentional about spending evenings in their front yard rather than their back yard so as to meet and interact with neighbors. Through small acts like these of connecting and paying attention to our neighbors’ lives, we begin to share the gospel. Suburban geography is uniquely suited to put us into relation with each other. Thomas Hochschild’s sociological research credits the cul-de-sac as an important space planning option: Those who live in cul-de-sacs both know their neighbors better and interact with them more than those on traditional through streets. Adopting this idea from suburban geography can foster evangelism, discipleship, service, and hospitality as we intentionally turn our hearts—not just our houses—toward one another. But it requires choosing to see our cul-de-sacs and neighborhoods not simply as where we live but where we love God, and it requires choosing to spend our resources of love, money, and time staying put there. As we grow to see our suburban lives given in service to loving Jesus and inviting others to know him, we can begin through the ancient Christian practice of hospitality—of making room. We may have grand or intimidating visions of what biblical hospitality looks like, be it a commune, a soup kitchen, or a pretty tablecloth laid with candles and charcuterie. But as we look at the life of Jesus, we see that he performed miracles in the context of daily life, 32 Hales P30.indd 32 often when he was on the road from one place to another. He turned water into wine at the request of his mother. He multiplied loaves and fishes for ordinary hungry people listening to him teach. He healed blind men, lepers, and a bleeding woman, and he raised people from the dead—all within the course of ordinary time on ordinary days. The gospel always comes to us in ordinary elements—in water, bread, and wine. As ordinary Christians on ordinary days in ordinary cul-de-sacs, we, too, can make room for others. Rather than playing into the trope of the suburbs as exclusionary, closed-off spaces, hospitality starts with opening up. We start by paying attention, then we learn to love what we pay attention to, so that evangelism and discipleship happen in our streets and connected houses. This is the sort of thing Catherine McNiel and her family committed to when they moved into a suburb where their neighbors aren’t predominately white or affluent. Rather than focus on programdriven outreach, for the McNiels, neighborly care and hospitality happen through birthday parties, in the dual-language school their children C H R I S T I A N I T Y T O D AY. C O M / W O M E N 7/17/19 11:50 AM PHOTO BY JAMES BREY / GETTY MAKING ROOM SPEAKING AND SERVING PHOTO BY JAMES BREY / GETTY The gospel calls us to front-yard, cul-de-sac hospitality— to be present to one another and the needs of our place. attend, and simply living life together. And it’s never one-way. Catherine says, “We don’t see ourselves as saviors; we see ourselves as neighbors.” Yet, something happens when volunteers from other more affluent suburbs come to participate in life alongside Catherine’s family—a sort of “alchemy” Catherine says only the kingdom of God can bring: Hierarchies crumble and everyone is changed. How do we make room for people and invite them to consider Jesus through the means of ordinary hospitality? Barna reports that 30 percent of lapsed Christians or non-Christians prefer “casual one-on-one conversation” about matters of faith—yet only about 20 percent of those polled say they have experienced this in the last year. These needed casual conversations can happen within relationships—between the soccer practices, coming home from work, grocery shopping, and errands. These steps toward deeper conversation can happen in our cul-de-sacs and driveways, at the post office, and on the street corner. The in-between moments and spaces in our lives can be an intentional setting where hospitality starts, just like for Catherine’s family. Small conversations and small acts of service bind a community together. When we lived in a different suburb years ago, we grabbed neighbors and, with a small child strapped to my back, together we gave a fresh coat of paint on cinder block walls along a main street. Stephanie Nelson, a children’s pastor in Manhattan, Kansas, volunteers in the local elementary school to teach character lessons in conjunction with the school counseling office. In the Denver suburbs, Mark and Chastity Gomez serve as foster parents and work part-time within their county to educate other foster parents. Community building is never just for us. When we come together with neighbors, we come not as people who have all the answers but as people who recognize our need for one another. The gospel calls us to front-yard, cul-de-sac hospitality— to be present to one another and the needs of our place. The gospel often starts small—as seed in the ground, in small talk, in service and generosity, and in common moments shared among ordinary days. Yes, God calls us to go to the “ends of the earth” (Matt. 28), but he also calls us to start by going next door: to listen, to invite, to create margin for our neighbors. We can do this when we’re at home, walking on the way, lying down, or getting up (Deut. 11:19). Our evangelism is the fruit of our hospitality, and it happens in the midst of everyday life with routine gestures of welcome and warm words of truth. Your real life in the place you live is the holy and ordinary ground upon which you live out your faith. The call of a missionary is not always to move to a new place, but it is always to make room right in the middle of your ordinary life, on your street, among your neighbors—for the gospel to flourish. ASHLEY HALES is a writer and speaker living in Southern California. Her first book is Finding Holy in the Suburbs: Living Faithfully in the Land of Too Much (InterVarsity Press). 33 Hales P30.indd 33 7/17/19 11:50 AM are missionary kids missionaries? FAMILIES IN THE FIELD SAY IT’S COMPLICATED. RACHEL JONES ILLUSTRATION BY MAGGIE CHIANG I In 1793, Dorothy Carey, pregnant with her fourth child, refused to accompany her husband, William, to India. He took their eldest son and boarded the ship without her. Evangelism over family! At the last minute, with one day to spare, friends convinced Dorothy to go. She hastily packed and boarded the boat. She subsequently lost one of her children (after losing two in England) and, eventually, her mind. In later generations, children as young as five were left in England or the United States while their parents served as missionaries abroad. Evangelism over family! For their education, for their protection, for the success of the mission. This history lingers in the subconsciousness of many Christians. One of the first questions today’s missionaries are asked when 36 Jones P36.indd 36 C H R I S T I A N I T Y T O D AY. C O M / W O M E N 7/29/19 8:32 AM 37 Jones P36.indd 37 7/17/19 12:13 PM they announce their intention to move abroad is “Are you bringing the children?” When the person asking contemplates the question, they retract it sheepishly. Of course the children are going. To Paris, Nairobi, Beijing, Beirut, La Paz. Once there, missionary parents face a relatively new question, one that few actively address before leaving their passport country but one that comes laden with unspoken expectations. What is the role of the family in kingdom ministry? Most other careers don’t inherently impact the language one’s children will speak or whether one’s family needs yellow fever vaccinations. IT’S COMPLICATED EARLY IDEALISM The question is complicated. A thorough answer requires consideration of physical context; type of missionary work; expectations of organizations and sending churches; the ages, personalities, and faith of the children; the personal conviction of parents; and more. The question is problematic. After all, are the children of surgeons involved in surgery? Are teachers’ kids expected to help plan lessons or grade exams? Does family play a role in trading stocks and bonds on Wall Street? There is an expectation, unique to ministry, that family will be intentionally involved in the missionary parent’s career. Today, supporters further expect to be able to follow all the details of the family’s “adventure” on social media. The question is also necessary. Mission work directly affects family life. A missionary career is all-encompassing. There's a physical move, maybe across the planet. All family members face culture shock. Schooling options shift. Relationships with relatives or friends change. Most other careers don’t inherently impact the language one’s children will speak or whether one’s family needs yellow fever vaccinations. I asked missionaries if they viewed their family as involved in their kingdom ministry. Responses fell loosely into three categories: Yes, absolutely. No way. Well . . . kind of ? Almost every response added something to the effect of “It’s complicated.” Jane, who served in East Asia, told me, “When we went overseas with our first child, I had grand visions of ministering to people as a family. It was exciting. We assumed that a thriving ministry meant having people in our home a lot. But this started to take a toll on our family.” Rachael Litchfield, who has served in Thailand and Cambodia, explained, “When we took our children to Southeast Asia, I imagined they would be totally at home with loads of local friends, speak the language fluently, and be integral to our family making an impact for the kingdom. In reality they, like us, had experiences both good and bad, went through ongoing culture stress, and grieved losses, especially in their transient relationships.” Jane and Rachael are not alone. Many of the missionaries with whom I spoke shared a similar grand vision, initially. Children are integrated into local schools or, because of a flexible homeschooling schedule, participate in outreach and service activities alongside their parents. The whole family is fluent, culturally competent, and delights in talking about Jesus. They form natural communities around children’s sporting or musical events, with neighbors, and with the families of the parents’ coworkers or ministry contacts. Their home is always open and a place of safety and connection. They are a missionary family, with a corporate vision of being a blessing among the nations, in word and deed. It is a beautiful ideal. Sometimes, this is actually what happens. 38 Jones P36.indd 38 C H R I S T I A N I T Y T O D AY. C O M / W O M E N 7/17/19 12:13 PM Amy was 13 when her parents and five sisters moved to Kenya, where her father worked as a missionary doctor. “From the beginning, my parents said they wanted us to be part of the ministry at the hospital. We went to the pediatric ward once a week, played with the kids, and sang songs. In high school, we helped with community health outreach and organized the hospital storage closets,” she explained. This influenced her heart for service and education and directed her future studies. “I’m very thankful for it,” Amy said. “My parents taught by example and helped me to learn a perspective that went beyond my own nose.” Incorporating the whole family in ministry normalizes what might seem radical and allows children to serve. Andie, working in Turkey, told me, “We encourage our kids to find ways to serve. Greet a visitor, sweep a floor, clean up a spill, work the projector. I don’t think of it as having to do with our ministry specifically. These are things I would encourage any new believer to do. Find a way to serve, even if it’s refilling the toilet paper.” Craig Greenfield and his wife, Nay, have raised their kids in Vancouver and Cambodia. Craig, author of Subversive Jesus, told me, “Where people [tend to] go wrong is divorcing ministry from lifestyle. Ministry becomes something outside the home. The home is dedicated to family. With that dichotomy, it’s difficult and even unnatural to involve kids. But when you live an intentional lifestyle following Jesus, it’s difficult not to include your kids.” In Canada, the Greenfields welcomed homeless friends and people struggling with addiction or prostitution. “They interacted with our children when they were in our home and sitting around our dinner table. Those interactions were some of the most healing times for our neighbors and friends.” Travis and Lydia, who serve in Kenya, shared how magnetic their children are. “My sons join me to visit a beloved Muslim friend to study the Bible and Qur’an,” Lydia said. “She spoils them as if they were her own grandchildren and they adore her snacks and tea. Week by week, they learn both about Islam and about their own faith in our ongoing discussions.” Including their kids in ministry also gives Travis and Lydia a chance to disciple their children and friends at the same time. “In discipleship, the demonstration of a normal and healthy family—hugging children, appreciating spouses, and so on—is the best way to teach family life,” they said. GROWING DISILLUSIONMENT Today’s social media interactions—the dopamine hit of likes and comments and the stream of opinions—can pressure missionary families to curate that ideal, uncomplicated image of family life in ways not experienced in previous generations. But families ministering together rarely look like that ideal image. Yes, children can be magnetic, but in some settings, foreign kids also attract unwanted attention and even aggressive touching of their hair or skin. One mother said, about bringing her boys to urban areas, “The kids there were 39 Jones P36.indd 39 7/17/19 12:14 PM so tough—hair-pulling and name-calling.” Parents must also be alert to realities of sexual harassment and assault, issues rampant around the world today but even more commonplace in cultures where women are regularly victimized. These difficult topics are not often discussed in pre-field orientations. Several parents expressed feeling unprepared for and surprised by these realities. Even when not abusive, the attention can be exhausting, especially when it invades home life. Abigail (a pseudonym) said her girls grow weary of needing to change from shorts into long skirts when Muslim friends visit their home. “But at the same time, they enjoy the interactions, so we try to strike a complicated balance,” she explained. While parents often assume their home will be a place of ministry, for many it can start to become a place of stress for their kids. Jane, who was initially excited about the possibilities of family and ministry, explained that as her daughter learned more of the language, “our outgoing daughter became withdrawn. She understood not only the praise heaped on her Not despite but in the struggles of family life, many missionaries developed a more nuanced form of authentic ministry— living out the gospel in the context of their own family’s needs, brokenness, difficulties, and limits. Jones P36.indd 40 but the criticism as well.” Jane’s husband also struggled and, instead of their home serving as a place of ministry, she says, “I ended up doing a lot of ministry out by myself.” Missionaries also can’t assume their children will share their beliefs as they age. In the era of social media, it is naïve for parents to think their children will be isolated from secular or other religious worldviews, even if they live in a rural location, are homeschooled, or are surrounded by Christian ministry. Jonathan and Elizabeth Trotter, missionaries in Southeast Asia and authors of Serving Well, addressed this. Elizabeth said, “We must give our children the choice to believe, just like our Father has given us the choice to believe. I cannot believe for them, but I can pray. I can model a faith that isn’t afraid to ask questions, and I can be unafraid of their questions.” Jonathan added, “Forcing missionary kids into a faith that is not yet their own risks alienation and anger. I would rather my kids be honest questioners than dishonest hypocrites.” Nor can missionaries assume their children will want to talk about Jesus, even if they do love him. Jonathan said, “Children of missionaries didn’t sign up to be missionaries, and the idea that our kids should be little evangelists for Jesus isn’t fair. It might look sweet early on, and supporters will eat it up, but it’s dangerous and too often damaging. Our kids didn’t go to seminary or prepare vocationally. They haven’t wrestled through the deep questions of calling. They’re just kids, and we should let them grow and develop as such.” Even when kids want to be involved in ministry with their parents, the culture in which they live can be prohibitive. Becky (a pseudonym), described to me her desire to have been more a part of her parents’ work in a strict Islamic area. “I wanted to be more involved but was held back by fear— fear of the unknown and of my inability to communicate. There were also limitations because of my gender. I was limited in relationships with boys my age. Many girls my age were either married or expected to be soon. Being part of my parents’ ministry wasn’t 7/17/19 12:14 PM what I was called to do in that point of my life, but being a member of my missionary family gives me responsibility to at least be partially involved. The extent of that was to pray and set a good example of how a Christian family relates.” A DIFFERENT REALITY Teenagers facing cross-cultural struggles, dangerous locations, harassment, foreign language learning, social media, security concerns—it all fits under the umbrella of “normal” in modern missionary family life. But it is not what many missionaries initially anticipate. This gap between an ideal and the reality can come as a shock. Most parents I spoke with expressed surprise, disappointment, even disillusionment, about the role their family actually played in their ministry. If parents are unable to adjust or abandon that ideal, if they face pressure from a sending organization or home church, if parents feel judged for the decisions they make (boarding school, homeschool, leaving the field, moving to a new location to avoid harassment, and so on), they struggle. Some start to question their family, their call, sometimes even their own faith. If we are trusting God, why is this so hard? What is the point of living here, away from grandparents and Target and English, just so I can change diapers or argue with my teenager? In Southeast Asia, Rachael enrolled her children as the only foreign kids in a national school. “They never became confident in the language. We all struggled with how they were singled out and with the totally unfamiliar approach to education and discipline.” When they relocated to a new country, they made a different educational choice: “When we moved to an international school setting, they began to thrive. Allowing them to be who they were and not placing my idealistic views of missionary life onto them, including using them to prop up my shaky self-image, freed us to simply be family.” Jane told me, “For a long time, I felt guilt— but I’ve realized a ministry that sacrificed my marriage or kids was not what God wanted.” Most of the people I spoke with expressed gratitude that, among missions organizations, there is a recent growing focus on healthy families. Organizations like the Navigators and AIM now offer counseling services, address special education needs for issues from ADHD to stuttering to dyslexia, and provide spiritual support over Skype. Some plan special conferences and retreats specifically for families or offer online parenting classes. “Our organization, Serge, sees us as a family unit, seeking to ensure that we are all well cared for and understanding that if the kids aren’t doing well, we won’t be able to continue,” Rachel McLaughlin, an ob-gyn in Burundi, said. One of the primary ways Serge does this is by encouraging missionaries “to preach the gospel not only to our host culture but to ourselves and our families every day.” GO AND BLESS As I heard from all around the globe—Hawaii to China, Kenya to Colombia—the picture of families involved in ministry together often moved from idealistic to painful to joyful and complicated, and finally, to life lived authentically, empowered by the Holy Spirit, alongside coworkers, neighbors, and friends. Not despite but in the struggles of family life, many missionaries developed a more nuanced form of authentic ministry—living out the gospel in the context of their own family’s needs, brokenness, difficulties, and limits. Family life abroad is complex and individual. This leaves little room for pride or judgment and a lot of room for learning. Rather than conforming to a façade of the perfect ambassador for Christ, missionary families live out the truth of grace, forgiveness, and redemption. Theirs is a proclamation that those who mourn are blessed—as are those who are persecuted for righteousness’ sake, who hunger and thirst, who are poor in spirit. These are not descriptions of the perfectly integrated cross-cultural family. But missionary families say these are accurate descriptions of a blessed and honest life—one lived in the pain of broken relationships and a sinful world, of natural disaster and disease, and with a God who is present in the trial and who offers restoration and redemption. RACHEL JONES works and writes in East Africa. Her next book, Stronger than Death, releases in October (Plough). 41 Jones P36.indd 41 7/17/19 12:15 PM my road to emmaus ran through east L.A. SUFFERING AND MINISTRY TURMOIL LEFT ME DEVASTATED. JESUS MET ME THERE. TERESA KU-BORDEN 44 C H R I S T I A N I T Y T O D AY. C O M / W O M E N Ku Borden P44.indd 44 7/30/19 8:42 AM PHOTO BY DACIAN GROZA / STOCKSY T The week I became a mother was the most beautiful and terrifying week of my life. On my son’s second day of life, my husband I were told that he had a rare form of jaundice, possibly caused by a congenital defect of the liver. One early morning as he was getting his blood drawn, I was shaken as I watched his tiny arms flail. Muffled by the clear incubator walls, his screams shattered my heart. All I wanted to do was hold him and take away all of his pain. Seven years before having a child, my husband, Ryan, and I lived in a small, mostly Latino community just a few miles northwest of East Los Angeles. Neither of us would have thought that we would make East Los Angeles our home. But during an urban ministry project, our visions and plans for our lives began to shift. We were inspired by ministers and followers of Jesus who relocated from more comfortable middle- and upper-class communities into neighborhoods of poverty to live in solidarity with people who were different from them. We had the same hope and intention. Ryan and I became part of a church-planting team in Lincoln Heights. Ryan started the high school ministry, and I started the path to becoming a physician. After some ministry mishaps and failures, the youth group began to thrive. Our youth opened their hearts and their lives to us, and we connected with them. We invited them into relationships with Jesus and did our best to nurture any spiritual hunger we encountered. We felt a sense of purpose as 20-something newlyweds who were seeking to live out what we understood of God’s calling on our lives. When it came time to move for my upcoming medical residency, it was difficult to say goodbye to this group of hungry and humble students. After four years of residency and my fellowship, we felt called to return to East Los Angeles. I was now pregnant, and we planned to pick up where we’d left off—to raise our child in this community that we loved. I looked forward to the next chapter of my life with hopeful anticipation. 45 Ku Borden P44.indd 45 7/17/19 12:20 PM I look back now on those well-thought-out, idyllic plans, and I smile wistfully to myself. I had based all those plans on my ideals and assumptions—that our son would be healthy, that we would be able to take him along to do ministry with us, and that our lives would continue to have the same sense of calling, purpose, and fulfillment. But our son was not healthy. Adam was diagnosed with biliary atresia, a congenital and progressive defect of the liver. We didn’t know how long he would remain healthy before his liver would fail and he’d need a transplant. Even though it was painful to hear, we also knew it was a sacred gift to be invited into these depths. The way we’d learned how to do ministry seemed to have backfired, causing more pain and distrust. I began to question my role and calling in this ministry context. The inner turmoil, the questions, the collision and intersection of my identities as mother, physician, and Chinese American woman—was it worth the cost? Had all of our “hard work” been for nothing? Did we even belong here? How could God have been in all of this? A SEASON OF SUFFERING OUR EMMAUS ROAD When we returned to our community and the small urban church we had helped to start, we were warmly welcomed back. But we quickly realized we had no capacity to do any ministry. We ourselves needed significant support as parents of a medically fragile child who was hospitalized nine times in the first 18 months of his life. We had never felt more isolated and alone. We were paralyzed by the trauma of having a very sick child, and we were exhausted. Was the Lord forgetting how faithful my husband and I had been to the ministry? The sacrifices we’d made? The ideals and assumptions I had about following Jesus as a naïve 25-year-old had completely broken down. As we began to open up about our suffering in this season, our friends—especially the youth we had invested in—began opening up about theirs. They not only shared stories of trauma from childhood and of anger about the inequality in their education and upbringing, but they also began to share their frustration and bitterness toward Ryan and me from when we had mentored them as teenagers. They felt that we had operated out of a project mentality, rather than from a genuine desire to get to know them as people, as though we were using their community and doing ministry there to feel better about ourselves. It became clear to us that even as we had earnestly tried to serve our young adult friends, there had been times when we had also hurt them deeply. When we listened to them, we felt a mixture of emotions. To be entrusted with their honest reflections was a privilege and a devastation. After six months of no hospital visits—a virtual miracle for our family—our son was hospitalized once again. His liver disease was worsening. I sobbed into the pillow as I held my two-year-old. I felt betrayed and abandoned by God. Much like the two travelers on the road to Emmaus in Luke 24:13–35, we too had our expectations and hopes of what Jesus could do in our lives and ministry. We dreamt of producing and witnessing the fruit of our hard work and perseverance. This Jesus, who had performed miracles and overturned the tables of the status quo, who preached freedom for the captives and sight for the blind, he would be the one who would transform our urban communities. He would be the one to heal my son. He would make everything better. And we would cheer him on from the sidelines. Little did we know how disappointed and devastated we would be. This Jesus—the one in whom the travelers had put their hope—was killed. They thought he had left them to face their world and problems alone. Their hopes were crushed. And the weight of their disappointment and grief was like a shroud covering their eyes, keeping them from recognizing him. Where was Jesus in their disappointment? Just like the early followers, we also questioned, Where was Jesus in our darkest moments? This mystery companion on the road to Emmaus engaged with the travelers in their pain and disappointment. Their hearts burned while he was with them, but they did not know it 46 C H R I S T I A N I T Y T O D AY. C O M / W O M E N Ku Borden P44.indd 46 7/17/19 12:21 PM until he performed the very gesture that caused their grief in the first place—the breaking of the bread, the breaking of his body. In this beautiful yet devastating act, their eyes were opened. It wasn’t until then that they realized he had been with them the whole time they were on the road. In the hospital room that night, my muffled cries into the pillow turned into a deeper grief over an incomplete, fragmented understanding of the living God. For two and a half years, I had No one wants to hear about the “failed” attempts at ministry. . . . And yet these stories matter, and without them we can miss the complexity of what God is doing in the world. longed for God to be Healer, to fix my son’s liver. But he wasn’t healed; he was getting worse. I needed God to be more than a Healer. I needed him to be with me in my pain, to be present in all things, to be Emmanuel, God with me. Then, somehow, through my tears, I realized Emmanuel, God with us, is the gospel—the fullness of the living God. HE IS EMMANUEL In my 20s, I found it much easier to trust in formulaic stories with happy endings and pithy verses from Scripture than to hear the raw and honest tales of the difficulties and failures of ministry. How many testimonies have I heard about some missionary giving up the comforts of life or undergoing some kind of suffering, whether or not it was the result of her choice, and then experiencing complete relief and faithful ministry? But not all stories end this way. Many go to the mission field with aspirations and dreams of changing the world or serving those on the margins, only to come back earlier than expected because of personal reasons, team difficulties, or unforeseen circumstances. No one wants to hear about the “failed” attempts at ministry, unreconciled differences among teammates, or the emotional and mental exhaustion from living in a foreign place. And yet these stories matter, and without them we can miss the complexity of what God is doing in the world. I used to think if I would trust in Jesus and give my life to him, seeking his kingdom first, that God would grant me the desires of my heart. I believed that life with God meant paying some manageable costs in ministry, and as a result, experiencing an otherwise problem-free life. But with this view, there was no place for the suffering present in our world, in my own life, and in my friends’ lives. There was no place for the sometimes unexplainable, unjust, unexpected long-suffering that Jesus himself experienced and promises to walk us through. He is Emmanuel. He is with me; he is with us. I am learning to feel the moments when my heart is burning within me so that I can recognize his presence while we are on the road. I trust that God is still holding the larger story of our family, and our home, just as he is holding the stories and struggles within the broader home we all have here in East Los Angeles. While there may be pain and heartache and misunderstanding as any of us journey together, we can hold onto an ever-present hope: the promise of Emmanuel, our God who walks with us. TERESA KU-BORDEN is a family physician. She lives with her family in East Los Angeles and leads a small group at New Life Community Church. This article is adapted, with permission, from the chapter “Emmanuel, God With Us” in the multi-author book Voices Rising: Women of Color Finding & Restoring Hope in the City (Servant Partners Press). www.servantpartnerspress.org/voicesrising. 47 Ku Borden P44.indd 47 7/22/19 2:03 PM rethinking how we talk about salvation PAUL’S FAVORITE DESCRIPTION IS A PHRASE WE RARELY USE. JULIE CANLIS 48 Canlis P48.indd 48 7/17/19 10:12 AM SOURCE PHOTO BY KAROLINA SKISCIM / UNSPLASH Y Years ago during graduate studies at Regent College, I had a desperate talk with Eugene Peterson about how my PhD had turned the words of God into a great big research project. I was trying to read my lifeless Bible, but I was interrupted 1,000 times by children needing to be fed, changed, read to, and more. I begged him to give me a spiritual discipline, some rope to haul me out of the hole I was in. “Well, Julie,” he said, “is there anything you are doing in a disciplined manner already?” I thought about my newborn daughter, Iona, and the hours I spent feeding her. She had reflux, and most of what went into her immediately came up again, which meant that I had to repeat the feeding all over again. “Nursing Iona is the only thing I can count on,” I said. “She makes sure of that.” He patted my hand, then, like a parent consoling a dissatisfied child who is not content with their lot in life. “Julie, that is your spiritual discipline. Now start paying attention to what you are already doing. Be present.” In that moment and many others like it, I was weakened by a common and insidious temptation: I wanted to be for Christ instead of being in Christ. I saw my familial responsibilities as obstacles to a godly life when in fact they were the very place he wanted to meet me. Accordingly, I had to radically revise my view of obedience to include the simple act of abiding in Christ. This idea of being “in Christ” is arguably one of the most potent—and perplexing—aspects of Paul’s letters. We tend to speak of salvation as “Jesus in my heart.” At least in recent history, evangelistic efforts have often centered on this metaphorical idea that a person asks God to come in and inhabit the heart. However, when we look at Scripture, the phrase “Jesus in my heart” is used only one time (Eph. 3:17). Its rhetorical cousin, the phrase “Christ in me,” is mentioned only five times in the Bible (2 Cor. 13:5, Rom. 8:10, Gal. 4:19, Gal. 2:20, Col. 1:27). By contrast, Paul says something far more often: He uses the phrase “in Christ” 165 times. The Bible’s favorite way of describing our salvation is one we rarely use. For Paul, salvation was simple: It was being joined to Jesus Christ. When I first began to study Paul, I glossed over this description, assuming it was just another way of talking about what Jesus did for me on the Cross. But the more I read Scripture, the more I realized that Paul was actually talking about being joined to Jesus. For me, this was a Damascus Road revelation. The scales fell from my eyes. This idea made so much more sense of commands that I obeyed but didn’t really understand—like getting baptized, going to church, taking Communion. Paul, too, is hit with the same truth of being “in Christ” when he encounters Jesus on the road to Damascus. He is breathing down the necks of Christians, ready to arrest them, when he's blinded by a flash of light. He falls to the ground and hears a voice saying, “Saul, Saul. Why are you persecuting me?” Saul asks, “Who are you?” And the voice says, “I am Jesus.” The voice doesn’t ask, “Why are you persecuting my people?” Instead, it explains that Saul’s actions against Christians are directly hurting Jesus himself, whom Saul had never seen, touched, or hurt. This dramatic experience revealed not only Jesus but, perhaps more importantly, the ongoing connection that Jesus had with his followers. This conviction grew and grew over Paul’s life. His letters are overflowing with references to “union with Christ.” 49 Canlis P48.indd 49 7/17/19 10:13 AM I wanted to be for Christ instead of being in Christ. In the introduction to his translation of the New Testament, J. B. Phillips writes of Paul and other New Testament writers, To these men it is quite plainly the invasion of their lives by a new quality of life altogether. They do not hesitate to describe this as Christ “living in” them. . . . We are practically driven to accept their own explanation, which is that their little human lives had, [in] Christ, been linked up with the very life of God. . . . These early Christians were on fire with the conviction that they had become, [in] Christ, literally sons of God; they were pioneers of a new humanity, founders of a new Kingdom. In this kingdom context, here is how union works: Paul believes that we are united to Jesus’ descent and his ascent. First, Christ joined himself to us in the Incarnation. This union is not subjectively experienced by us but is an objective, cosmic miracle of God uniting himself to our humanity. This extraordinary event doesn’t get activated by our faith or by praying a prayer. Rather, it has already happened—it just is. The second part of the mystery is even greater: Jesus has thrown open his history to us. This is the subjective, personal part that we are invited to step into. The Spirit says to each one of us, “Okay, who’s in?” Then we are ushered into the Spirit’s primary work in the universe—to put all things into Christ and to be joined to him. Together, these two unions are the huge, creation-encompassing ideas that we find in Paul’s letters. When we say, “I have been crucified with Christ and I no longer live, but Christ lives in me” (Gal. 2:20), it is not a mindfulness technique or a positive-thinking exercise. This is our new reality. Our job is to wake up to it. All of the big theological words—justification, sanctification—now make sense in this orbit of being “in Christ.” As we think about identity in Christ, we ponder it not only for ourselves but also for others—especially those who don’t yet know saving faith. In the context of evangelism, we’re inviting unbelievers to join not just the body of Christ but Christ himself. Here again, these two unions come into play: First, the greatest agency and the greatest action come not from seekers poised on the edge of conversion but from God himself. Salvation has already been accomplished on the Cross, and those who desire to know Jesus don’t have to strive after or fight to feel its impact. They simply step into a new reality. The second, subjective aspect of sanctification, however, does involve a response. An unbeliever is invited by the Holy Spirit to proclaim, “Yes, I’m in,” to stand at the feet of Jesus and say, “I believe. Help my unbelief” (Mark 9:24, NASB). “Help me to participate in God’s ongoing work in the world.” 50 Canlis P48.indd 50 So how do we—new Christians and old—enter all of this? How do we abide in Christ? First, the church is the context for our union with Jesus. The church isn't merely a building or a community of people. It exists in union with Christ. When you are united to Christ, you are put into a family. There are no “only children” in the kingdom. Second, if the church is the primary context for abiding in Christ, then baptism in the church enacts our union with him. Paul says that “if we have been united with him in a death like his, we will certainly also be united with him in a resurrection like his” (Rom. 6:5). In baptism, we experience the gospel in water. We physically declare that we are dying to all attempts to “be ourselves” apart from Christ and instead are raised to new life in him. Finally, the Lord’s Supper nurtures our union with Christ. If union is God’s embrace of us, then Communion is our throwing ourselves into the arms of his loving embrace. In Communion, we are eating the good news of our connection with Christ. As Paul writes, “Is not the cup of thanksgiving for which we give thanks a participation in the blood of Christ? And is not the bread that we break a participation in the body of Christ?” (1 Cor. 10:16). Doing something “for Christ” is a very different action than being “in Christ” and although both bear important fruit for the kingdom, for most of us, being in Christ poses the greater challenge. As Eugene Peterson taught me years ago, we find our salvation in the simple habits of our daily lives. As we parent, we do so in union with Christ. As we work, we do so in union with Christ. As we face illness or despair, we do so in union with Christ. Not unlike the child I breastfed those years ago, we are sustained by Christ daily, hourly— even when we are most unaware. JULIE CANLIS is the author of A Theology of the Ordinary and Calvin’s Ladder. She co-produced the film Godspeed. C H R I S T I A N I T Y T O D AY. C O M / W O M E N 7/17/19 10:13 AM I with one voice when it came to Christianity. Cultural anthropologist and Naga tribe member Kanato Chophi stated it most starkly: “We must abandon this absurd idea that Christianity is a Western religion.” DIVERSE FROM THE START I met Senganglu Thaimei (Sengmei to her friends) in New Delhi, India. Born to the Rongmei tribe in the extreme northeast of India, she teaches English literature at Delhi University and writes stories reimaging the tales of her tribe through the eyes of marginalized women. Sengmei is keen to preserve tribal culture, and preservation is necessary. The Naga tribes were reached by Western missionaries in the 19th century. Christianization brought westernization. Today, over 80 percent of the Rongmei are Christian, and tribal traditions are declining. For many, this would be one evidence among many that Christianity is a white, Western religion forcibly exported to other cultures and leaving a trail of cultural destruction in its wake. But the rest of Sengmei’s story complicates the picture. Raised in a nonreligious home, she started following Jesus as a teenager through the witness of a Rongmei friend. Today, she is a passionate Christian and her husband (from a kindred tribe) pastors a multiethnic church. What’s more, as we discussed the history of her tribe, Sengmei warned me not to give Western missionaries too much credit. Westerners saw only a handful of Naga converts, who then effectively evangelized their tribes. And while Sengmei deplores the ways Western culture was illegitimately packaged with Christianity, she is equally clear about the positive effects of Christianization, especially for tribal women. I visited India to meet with 12 Christian academics. Ten came from Naga tribes. Between them, they spoke seven indigenous languages. But they spoke 54 Centuries of Western art depicting Jesus as fair-skinned may incline some of us to forget that he was a Middle Eastern Jew who lived under oppressive Roman rule and whose followers were first called “Christians” in Antioch—the ruins of which lie in modern-day Turkey. Christianity did not come from the West. But nor was it constrained by its culture of origin. Jesus’ life and teachings scandalized his fellow Jews by tearing through their racial and cultural boundaries. For instance, the hero of the Parable of the Good Samaritan came from a hated ethnic group. Jesus commanded his disciples to “go and make disciples of all nations” (Matt. 28:19). They began at once. In Acts, we see the Spirit enabling the apostles to evangelize people “from every nation under heaven” (Acts 2:5), including those from modern-day Iran, Iraq, Turkey, and Egypt (Acts 2:5–11). This move of the Spirit to communicate in the heart-language of those listening is one evidence among many that Christianity is a multicultural and multilingual movement. In fact, the Bible itself is multilingual! The Old Testament is in Hebrew and the New Testament in Greek. But Jesus’ mother tongue was Aramaic, and the Hebrew Scriptures were mostly accessed by first-century Palestinian Jews via Aramaic translations. We see traces of Jesus’ first language in Mark, when he raises a little girl (Mark 5:41), heals a deaf man (7:34), and cries out to his Father on the cross (15:34). The criminal charge posted at the cross (“Jesus of Nazareth, King of the Jews”) was written in C H R I S T I A N I T Y T O D AY. C O M / W O M E N McLaughlin P54.indd 54 7/17/19 12:25 PM three languages—Aramaic, Latin, and Greek—to cover the relevant languages of the time (John 19:20). But there is no single language of Christianity. THE DIVERSITY OF THE EARLY CHURCH It is a common misconception that Christianity first came to Africa via white missionaries in the colonial era. In the New Testament, we meet a highly educated African man who became a follower of Jesus centuries before Christianity penetrated Britain or America. In Acts 8, God directs the apostle Philip to the chariot of an Ethiopian eunuch. The man was “a court official of Candace, queen of the Ethiopians, who was in charge of all her treasure” (Acts 8:27, ESV). Philip hears the Ethiopian reading from the Book of Isaiah and explains that Isaiah was prophesying about Jesus. The Ethiopian immediately embraces Christ and asks to be baptized (Acts 8:26–40). We d o n ’t k n ow h ow p e o p l e responded when the Ethiopian eunuch took the gospel home. But we do know that in the fourth century, two slave brothers precipitated the Christianization of Ethiopia and Eritrea, which led to the founding of the second officially Christian state in the world. We also know that Christianity took root in Egypt in the first century and spread by the second century to Tunisia, the Sudan, and other parts of Africa. Furthermore, Africa spawned several of the early church fathers, including one of the most influential theologians in Christian history: the fourth-century scholar Augustine of Hippo. Likewise, until they were all but decimated by persecution, Iraq was home to one of the oldest continuous Christian communities in the world. And returning to Sengmei’s homeland, far from only being reached in the colonial era, the church in India claims a lineage going back to the first century. While this is impossible to verify, 56 leading scholar Robert Eric Frykenberg concludes, “It seems certain that there were well-established communities of Christians in South India no later than the third and fourth centuries, and perhaps much earlier.” Thus, Christianity likely took root in India centuries before the Christianization of Britain. EVERY TRIBE, TONGUE, AND NATION Many of us associate Christianity with white, Western imperialism. There are reasons for this—some quite ugly, regrettable reasons. But most of the world’s Christians are neither white nor Western, and Christianity is getting less white and less Western by the day. Today, Christianity is the largest and most diverse belief system in the world, representing the most even racial and cultural spread, with roughly equal numbers of self-identifying Christians living in Europe, North America, Latin America, and sub-Saharan Africa. Over 60 percent of Christians live in the Global South, and the center of gravity for Christianity in the coming decades will likely be increasingly non-Western. According to Pew Reseach Center, by 2060, sub-Saharan Africa could be home to 40 percent of the world’s self-identifying Christians. And while China is currently the global center of atheism, Christianity is spreading there so quickly that China could have the largest Christian population in the world by 2025 and could be a majority-Christian country by 2050, according to Purdue University sociologist Fenggang Yang. To be clear: The fact that Christianity has been a multicultural, multiracial, multiethnic movement since its inception does not excuse the ways in which Westerners have abused Christian identity to crush other cultures. After the conversion of the Roman emperor Constantine in the fourth century, Western Christianity went from being the faith of a persecuted minority to being linked with the political power of an empire—and power is perhaps humanity’s most dangerous drug. But, ironically, our habit of equating Christianity with Western culture is itself an act of Western bias. The last book of the Bible paints a picture of the end of time, when “a great multitude that no one could count, from every nation, tribe, people and language” will worship Jesus (Rev. 7:9). This was the multicultural vision of Christianity in the beginning. For all the wrong turns made by Western Christians in the last 2,000 years, when we look at church growth globally today, it is not crazy to think that this vision could ultimately be realized. So let’s attend to biblical theology, church history, and contemporary sociology of religion and, as my friend Kanato Chopi put it, let’s abandon this absurd idea that Christianity is a Western religion. REBECCA MCLAUGHLIN, PhD, is the author of Confronting Christianity and cofounder of Vocable Communications. Content adapted from Confronting Christianity: 12 Hard Questions for the World’s Largest Religion by Rebecca McLaughlin, ©2019. Used by permission of Crossway, a publishing ministry of Good News Publishers, Wheaton, IL 60187. www.crossway.org. C H R I S T I A N I T Y T O D AY. C O M / W O M E N McLaughlin P54.indd 56 7/17/19 12:29 PM 8 books to expand your vision for missions COMPILED BY KELLI B. TRUJILLO 60 Trujillo P60.indd 60 C H R I S T I A N I T Y T O D AY. C O M / W O M E N 7/17/19 1:18 PM OUT OF THE SALT SHAKER & INTO THE WORLD BY REBECCA MANLEY PIPPERT INTERVARSITY PRESS I first came across Out of the Salt Shaker & into the World as a student in Brazil. It had a huge impact on me because it addressed my biggest obstacle when sharing Jesus with my friends: fear of rejection. Pippert encourages us to be authentic with our friends and dependent on Jesus. Little did I know how this was going to be crucial to the calling God had for my life. As I now travel across Europe training students in evangelism, fear of rejection is still the number one obstacle for students, just as it had been for me. This book is a must-read for any Christian who desires to be salt and light in their context. It teaches us how to partner with God in what he is doing in the lives around us, equips readers with communication skills to have natural conversations, and calls us to depend on the Holy Spirit in his work of salvation. LEADERS IN MISSIONS, MISSIOLOGY, EVANGELISM, AND GLOBAL MINISTRY REVEAL THE TITLES THAT SHAPED THEIR VISION AND EQUIPPED THEM TO BETTER PROCLAIM THE GOSPEL. SARAH BREUEL serves as director of Revive Europe, as evangelism training coordinator for IFES Europe, and as a member of the Lausanne Movement’s board of directors. FAITHFUL WOMEN AND THEIR EXTRAORDINARY GOD MICHELLE PHOTO BY ELEVATE DIGITAL STUDIOS BY NOËL PIPER CROSSWAY Faithful Women and Their Extraordinary God offers the church two needed narratives. The first is a theology of suffering and risk. Christians are a called and sent people. This book helps us understand that suffering is part of our story. The second narrative is the gifting and calling of women in God’s mission. The women featured in this book were powerfully used by God to spread his gospel and build his MICHELLE ATWELL is the US church. They taught, they shepherded, director of SEND they led, they served, and they blazed new International. and difficult trails. This book challenged me to consider what sacrifice, risk, and suffering look like when making a bold stand for Jesus. Each of these women made huge sacrifices in being obedient to God’s call. They persevered despite unimaginable suffering and trauma. They did not lose their faith; rather, they clung all the more tightly to their Lord. This book teaches us what it means to be wholly dependent on God and to remain faithful to him, no matter the circumstances. 61 Trujillo P60.indd 61 7/17/19 1:18 PM THE PRACTICE OF THE PRESENCE OF GOD THE LOCUST EFFECT BY GARY HAUGEN & VICTOR BOUTROS OXFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS 62 Trujillo P60.indd 62 This book features real-life accounts of refugees who encountered Jesus through the intentional hospitality and care of the global church. It challenged me to consider how a well-developed theology of hospitality can transform lives. Refugee Diaspora looks at the current refugee crisis through the lens of opportunity, namely, opportunities to be involved in caring for displaced persons in one’s community. It introduces JAMIE N. SANCHEZ is assistant professor us to real people, not just “refugees”(which and director of the has become a broad category devoid of PhD program in any personal characteristics). The stories Intercultural Studies transport the reader to different regions at Biola University. of the world where harrowing journeys are met with miraculous moments that transform lives. “Learning the art of biblical hospitality is a lifelong discipleship matter,” write the authors. “It requires a longing to reflect God’s heart for the marginalized in our world.” This book helps readers understand how God is moving in the midst of the current refugee crisis and how we can be involved in that movement. C H R I S T I A N I T Y T O D AY. C O M / W O M E N 7/17/19 1:22 PM RUTH PHOTO BY MATT KIRK BY SAM GEORGE & MIRIAM ADENEY WILLIAM CAREY PUBLISHING JAMIE PHOTO COURTESY OF BIOLA UNIVERSITY REFUGEE DIASPORA WENDY PHOTO BY NANCY LOVELL PHOTOGRAPHY EMELITA GODDARD is director of community development and agriculture for World Hope International. When I started reading The Locust Effect, I was immediately heartbroken. It begins with the story of “Yuri,” a young Peruvian girl who was raped and murdered. Yuri’s family had no financial means to bring her killer to justice. Like Yuri, millions of the world’s poor are silent victims of rape, murder, forced labor, and broken justice systems. This book challenged me to see the ugly underside of poverty, especially as ELIZABETH URIYO is the senior my colleagues and I at Compassion Intervice president national pursue our mission of releasing of Compassion children from poverty in Jesus’ name. International’s Global The church and other organizations Leadership Office. are behind life-changing efforts to alleviate poverty by addressing physical, social, educational, and spiritual needs. Countless lives are being saved and improved, but much of this work is undermined when the global poor are subjected to such violence. For me, it’s about urgency. This book is a wake-up call for the church to rise up and take a more prominent role in protecting the vulnerable poor. EMELITA PHOTO BY SCOTT GRIFFITH / COURTESY OF WHI-AUSTRALIA When I got this little book as a postgraduate student in Thailand in 1986, I was inspired by the life of Brother Lawrence and how he practiced the presence of God. It made me realize that I could talk to Jesus in simple ways, in heart-to-heart conversation with him. This book remains my key inspiration. When I spend time with the people I work with, Jesus is with me. He is always my companion. At World Hope, we work among the most discriminated-against sections of society. I work among the rural poor communities of Cambodia, Laos, Myanmar, Thailand, Vietnam, Indonesia, Nepal, and Bangladesh. When I go to the mountains among an ethnic-minority community, Jesus is with me. When I listen to the pain of people discriminated against by society, Jesus is with me. I can sense the love and compassion of God when I spend time in these communities, meeting survivors of human trafficking, gender-based violence, sexual exploitation, and other marginalized populations. Brother Lawrence’s prayer, “Lord, I cannot do this unless Thou enablest me,” has also been true for me. I recommend this book to all Christians, and especially to those who’ve been in ministry and feel burnt out. This little book is like a match to light the candle we need to carry in our journey with Jesus. ELIZABETH PHOTO COURTESY OF COMPASSION INTERNATIONAL BY BROTHER LAWRENCE HALF THE CHURCH BY PAUL BORTHWICK INTERVARSITY PRESS BY CAROLYN CUSTIS JAMES I was introduced to Western Christians in Global Mission as a student in the School of Intercultural Studies at Fuller Seminary and while serving as an executive with Wycliffe Bible Translators (USA). One theme in the text is Borthwick’s love for the church—both the North American church and the majority-world church—a love that is too great to let either get a free pass when it comes to the issues and RUTH HUBBARD serves as director challenges each brings. Borthwick helps of Urbana and as realign our Western thinking about mina vice president of istry partnerships to a more helpful and InterVarsity Christian accurate model. Fellowship. Today, I lead Urbana, a conference with the vision of seeing this and every student generation give their whole lives to God’s global mission. One question I’ve been asking with renewed passion is how we can more effectively model and call people to humility in serving crossculturally. Borthwick shines a glaring light on a reality that makes me uncomfortable in a good way. He states that, too often, we who serve on cross-cultural short-term missions practice self-congratulatory servanthood. Ouch! Borthwick’s litmus test for true servanthood is serving people in a way that they interpret as servanthood. ELIZABETH PHOTO COURTESY OF COMPASSION INTERNATIONAL THE VERY GOOD GOSPEL RUTH PHOTO BY MATT KIRK BY LISA SHARON HARPER WATERBROOK WENDY PHOTO BY NANCY LOVELL PHOTOGRAPHY JAMIE PHOTO COURTESY OF BIOLA UNIVERSITY EMELITA PHOTO BY SCOTT GRIFFITH / COURTESY OF WHI-AUSTRALIA WESTERN CHRISTIANS IN GLOBAL MISSION This quote in The Very Good Gospel stopped me in my tracks: “If one’s gospel falls mute when facing people who need good news the most—the impoverished, the oppressed and the broken—then it’s no gospel at all.” It caused me to take a deep, hard look at my life and ask myself: Is the CHI CHI OKWU is a senior church advisor Good News of the gospel evident in my life for World Vision. and to those around me, specifically the poor, broken, and oppressed? The book’s central theme of shalom has changed the way I engage in the work of justice. Shalom calls us beyond just fixing the immediate situation; shalom invites us to ask ourselves, What would it take for everyone to flourish? It’s easy to get caught up in a savior complex when you’re engaged in missions or justice work, but shalom requires us to remember that we are all connected—that when my sister is suffering, I too am suffering. The Very Good Gospel invites us into the redemptive work of God seeking to restore our broken relationship with God, humanity, and the earth. ZONDERVAN As I've equipped women in the US and abroad over 30 years, I felt concern about how our theological conversations didn’t seem to adequately address how creation and redemption engaged women in their full dignity as kingdom servants, nor how the Fall and human brokenness contributed to women’s extensive suffering around the world. Half the Church was an answer to prayer for me. Through exploration rather than debate, James offers thoughtful biblical work and fresh language that lends breadth and depth to our understanding and practice regarding women and men as God’s “blessed alliance” in the world. As I’ve led discussions with men and women from across the evangelical spectrum, this book has been a launching point for respectful, transforming conversation. We can process together—agreeing and disagreeing as we go—and all move closer to being the people God desires us to be. Redeemed men and women are both freed to be the kingdom people God intends, bringing that Good News into the cultures we serve so that his will is done “on earth as it is in heaven.” Half the Church gives women a greater sense of our identity as God’s daughters, and our calling as co-warriors with the men in our lives, so that we all live out Jesus’ call to follow him. WENDY WILSON is Missio Nexus’s mission advisor for the development of women and founder of Women’s Development Track. 63 Trujillo P60.indd 63 7/17/19 1:23 PM unburdening evangelism HOW THE PARABLE OF THE SOWER FREES US FROM A RESULTS-DRIVEN WORLD. SHARON HODDE MILLER 66 Miller P66.indd 66 C H R I S T I A N I T Y T O D AY. C O M / W O M E N 7/30/19 8:43 AM H How can we evangelize with integrity? As my husband and I lead our church together, this is a question we wrestle with a lot. Namely, in our enthusiasm to see people come to know Christ, how do we resist the temptation of results-driven ministry? How can we communicate the urgency of the gospel without manipulating others’ emotions or fears? How can we present the gospel in a way that is inviting without truncating the message to make it more palatable? As we have processed these questions and temptations regarding evangelism, we have found ourselves both chastened and encouraged by the Parable of the Sower (Matt. 13). In this famous story, Jesus uses an analogy that would have been familiar to his Palestinian audience. According to Bible scholar William Barclay, farmers at the time would have sown their seed in one of two ways: either casting out the seed by hand or strapping a bag of seed to the back of a donkey, tearing a hole in the sack, and letting the seed spill out as the animal crossed the field. In both scenarios, the seed would have been vulnerable to variables such as wind or rocky terrain, but because of these two different practices, the identity of the “sower” in this parable remains unclear. Perhaps we are the human sower, or perhaps we are the farmer’s donkey, but it is “God who gives the growth” (1 Cor. 3:7, ESV). In this way, the parable is symbolic of three “actors” who are present in the sharing of the gospel—you, the hearers, and God—and until we understand these roles properly, the work of evangelism will be much harder and more burdensome than God ever intended. YOUR ROLE In Matthew 13, the sower goes out to sow (v. 3), and he sows into all sorts of soil. What is strange about this sower, however, is that he sows haphazardly. He sows into bad soil and good. There is a recklessness to the sower. He does not pause to consider whether the seed can take root; he simply gives every soil the opportunity, and Jesus explains that our assignment is the same. It is not our role to judge the quality of the soil but simply to cast the seed. On the other hand, the sower’s “recklessness” should not be mistaken for carelessness, thoughtlessness, or laziness. In addition to sowing, a good farmer also cultivates his soil by loosening it and fertilizing it. The Parable of the Sower does not describe this work, but all of Scripture is brimming with instructions for cultivating the soil of our culture. When Christians are exhorted to “conduct yourselves with wisdom toward outsiders” (Col. 4:5, NASB), “keep your behavior excellent among the Gentiles” (1 Pet. 2:12, NASB), “speak up and judge fairly; defend the rights of the poor and needy” (Prov. 31:9), be known by your love (John 13:35), and be “all things to all people” (1 Cor. 9:22), these actions have a way of loosening and preparing the soil around us. Much of Jesus’ ministry work was soil work. He intervened on behalf of the woman caught in adultery before he exhorted her to sin no more (John 8). He reached out to the woman at the well, a social outcast, before dispatching her to evangelize her town (John 4). And he dignified the sinful woman, inviting her to anoint his feet and setting her free in forgiveness (Luke 7). By loving people, healing people, listening to people, and speaking in a language they could understand, he prepared the way for the seed to fall on fertile ground. For those of us who are prone to blame the world for its inability to hear, this perspective is a helpful corrective. THE HEARER’S ROLE For others of us, we place too much responsibility on ourselves to change hearts. Whether we do so because of pride or a lack of trust in God, this parable is a corrective for us also. In his commentary on Matthew, R. T. France writes, “The description of the four types [of soil] focuses, as surely as the parable intended, on their varying receptiveness to what they hear. All hear the same word.” Jesus describes three types of soil where even the best seed will struggle to grow: the hard path (Matt. 13:4), the rocky soil (v. 5), and the thorny ground (v. 7). The path, Barclay explains, would have been hard as pavement, packed down by the foot traffic of passersby, and it represents those hard-hearted and close-minded individuals who 67 Miller P66.indd 67 7/17/19 12:36 PM cannot receive the Word due to their prejudice, an unteachable spirit, an immoral character, or a wound from the past. The rocky soil represents a shallow faith, marked by chasing after the latest trend instead of cultivating something that lasts. Theologian Stanley Hauerwas describes this kind of Christian as one who is “too ready to follow Jesus,” meaning they “fail to understand that [they] do not understand what kind of Messiah this is.” They do not count the cost, and because of this, their faith is easily distracted or destroyed. In the case of the thorny ground, the soil is good but “is already taken up” by what France calls “cares and delights.” Whether it is the temptation of ease It is not our role to judge the quality of the soil but simply to cast the seed. or the busyness of over-commitment, this seed fails to grow and thrive because it is simply crowded out. Finally, Jesus describes the only good soil conducive to long-lasting growth. It is the heart and mind that is open to God, ready to hear, eager to understand, and willing to count the cost. In this parable, we encounter four different types of soil representing a thousand different stories and circumstances. At any given time, in any given church, women’s retreat, bookstore, or coffee shop, hearers are coming with their different states of soil. Many are not even what they appear. Some will be reserved yet more than ready to hear, while others seem curious but cannot, in actuality, be convinced. These soil conditions are too many for any one person to predict or imagine, which is why Jesus tasks us with a lighter burden: simply casting out seed. We do not have to anticipate every possible objection. In fact, this parable promises that some of our seed will not take root, and we are expected to cast it out anyway. We do not have to bend or twist or perform all sorts of acrobatic interpretive work to persuade the unpersuadable. That work is up to God. 68 Miller P66.indd 68 THE SPIRIT’S ROLE So much of horticulture is outside of human control. We cannot control the elements. We cannot control the wind, the drought, the floods, or the pests. Sowing the Word of God is similar—there is much we cannot control. In 1 Corinthians 3:6, the apostle Paul makes an important observation about the work of sowing. He affirms the value of evangelism, and he doggedly casts out seed, but he also writes, “I planted the seed, Apollos watered it, but God has been making it grow.” When it comes to evangelism, our role matters— but our role is also limited, and this truth can unburden us. Whenever we feel the pressure to convince people or feel tempted to make our gospel “nicer,” we are wise to remember that salvation is the Spirit’s work. The Spirit can take our words and make them just the right shape for another’s heart. The Spirit can translate our message about one situation into a myriad of different life scenarios. If anyone is going to break up the hard soil of a person’s heart, it is going to be the Spirit of God. If anyone is going to clear away the rocks and the thorns, it is going to be the Spirit of God. We may cast out the seed, but it is the Spirit who does all the heavy lifting. We do not have to transform the message for the benefit of hearers; instead we trust the Spirit to transform them. EVANGELISM’S ONE SURE THING Evangelism challenges our desire for resolution. We often want results we can point to—and faithful evangelism cannot promise us this. The Parable of the Sower meets us in this ambiguity, as does Jesus himself. Not only does our Savior cast out the seed of his words, but he also casts out the seed of his life. It strikes me that some approaches to evangelism neglect the sowing of our words, while others neglect the sowing of our lives. But, as Jesus’ followers, we are called to follow him in both. We sow by speaking the whole truth with boldness and by laying our lives down in love. Neither guarantees a response in our hearers’ lives, but they do guarantee one thing: granting as many people as possible a glimpse of the coming kingdom of God. SHARON HODDE MILLER, PhD, is the author of Nice: Why We Love to Be Liked and How God Calls Us to More and Free of Me (Baker Books). C H R I S T I A N I T Y T O D AY. C O M / W O M E N 7/17/19 12:37 PM