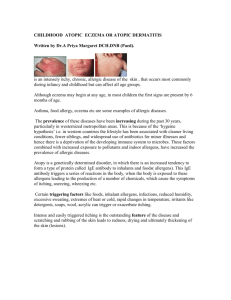

INTRODUCTION The word ‘eczema’ comes from the Greek for ‘boiling’ – a reference to the tiny vesicles (bubbles) that are often seen in the early acute stages of the disorder, but less often in its later chronic stages. ‘Dermatitis’ means inflammation of the skin and is therefore, strictly speaking, a broader term than eczema The terms eczema and dermatitis are used interchangeably, denoting a polymorphic inflammatory reaction involving the epidermis and dermis Eczema: a working classification • Exogenous (contact) factors – Irritant – Allergic – Photodermatitis • Other types of eczema (endogenous) – – – – – – – – Atopic Seborrhoeic Discoid (nummular) Pompholyx Gravitational (venous, stasis) Asteatotic Neurodermatitis Ptyriasis alba ATOPIC DERMATITIS The word ‘atopy’comes from the Greek (a-topos meaning ‘without a place’) It was introduced by Coca and Cooke in 1923 and refers to the lack of a niche in the medical classifications then in use for the grouping of asthma, hay fever and eczema. DEFINITION Atopic dermatitis is a difficult condition to define because it lacks a diagnostic test and shows variable clinical features. Atopic dermatitis is an (( itchy, chronic, or chronically relapsing, inflammatory skin condition)). The rash is characterized by itchy papules (occasionally vesicles in infants) which become excoriated and lichenified, and typically have a flexural distribution. EPIDEMIOLOGY Age of Onset First 2 months of life and by the first years in 60% of patients. 30% are seen for the first time by age 5, and only 10% develop AD between 6 and 20 years of age. Rarely AD has an adult onset. Gender Slightly more common in males than females. Prevalence Between 7 and 15% reported in population studies in Scandinavia and Germany, Prevalence of AD has been increasing since World War II. AETIOLOGY The inheritance Exacerbating Factors Eliciting Factors The inheritance The inheritance pattern has not been ascertained. However, in one series, 60% of adults with AD had children with AD. The prevalence in children was higher (81%)when both parents had AD. ELICITING FACTORS • Inhalants Specific aeroallergens, especially dust mites and pollens, have been shown to cause exacerbations of AD. • Microbial Agents Exotoxins of Staphylococcus aureus may act as superantigens and stimulate activation of T cells and macrophages. • Autoallergens IgE antibodies directed at human proteins, release of autoallergens from damaged tissue trigger IgE or T cell responses, suggesting maintenance of allergic inflammation by endogenous antigens. • Foods Subset of infants and children have flares of AD with eggs, milk, soybeans, fish, and wheat. Exacerbating Factors • Skin Barrier Disruption: increase transepidermal water loss by frequent bathing and hand washing and dehydration • Infections: S. aureus present in severe cases; rarely fungus (dermatophytosis, candidiasis). • Season: AD improves in summer, flares in winter. • Clothing: Wool is an important trigger; wool clothing or blankets (also wool clothing of parents) • Emotional Stress: results from or an exacerbating factor in flares of the disease. PATHOGENESIS SKIN BARRIER IMMUNOL OGIC GENITIC PHARMAC OLOGIC ENVIRONM ENAL Genetics The inheritance were recognized early, Higher risk was associated with maternal rather than paternal atopy. The chromosomal regions 3q21 and 5q31 have been linked to elevated serum IgE levels and AD. “Loss-of-function” mutations in the gene encoding filaggrin; underlie ichthyosis vulgaris, accompanied by AD in half of cases. Skin Barrier Dysfunction xerosis is hallmarks of AD , which affects lesional and nonlesional skin areas increasing transepidermal water loss, favor the penetration of high-molecular-weight structures such as allergens, bacteria, and viruses. Several mechanisms have been postulated: 1) decrease in skin ceramides, serving as the major water-retaining molecules in the extracellular space 2) alterations of the stratum corneum pH 3) overexpression of the chymotryptic enzyme (chymase) 4) defect in Filaggrin IMMUNOLGICAL 1) Elevated serum Ig E in majorty of case type 1 hypersensetivity reaction 2) Increase number of Th2 ??????? The hygiene hypothesis Low birth weight Maternal smoking Early infection with with respiratory syncytial virus Vaccination against Bordetella pertussis Early allergen contacts. CLINICAL FEATURES Atopic dermatitis is an itchy, chronic, fluctuating disease that is slightly more common in boys than girls, with a range of clinical features. The age of onset is between 2 and 6 months in the majority of cases, but it may start at any age, even before the age of 2 months in some cases. The distribution of the eruption varies with age. Infantile phase most frequently start on the face, but may occur anywhere. Often, the napkin area spared The lesions consist of erythema and discrete or confluent oedematous papules. The papules are intensely itchy, and may become exudative and crusted as a result of rubbing. Secondary infection and lymphadenopathy are common. Childhood phase The lesions are papular, lichenified plaques, erosions, crusts, especially on the antecubital and popliteal, the neck ‘atopic dirty neck’ and face; may be generalized Adult phase There is a similar distribution, mostly flexural but also face and neck, with lichenification and exoriations being the most conspicuous symptoms. May be generalized. Associated Clinical Features Pruritus • the hallmark of AD. • worse in the evening, by sweating or wool clothing. • The rubbing and scratching exacerbate pathogenic events >> the dermatitis. Excoriations • Scratching & rubbing can produce lichenified plaques and prurigo nodularis. Xerosis cardinal feature of AD (dry, scaly skin in a generalized distribution ( beyond areas of active dermatitis). Xerosis seen in 80–98% of AD patients. Impaired epidermal barrier function decreased water content in the stratum corneum >>> easier entry of irritants, promotes pruritus and initiate an inflammatory response. Keratosis pilaris • Excessive keratinization leading to horny plugs within hair follicle orifices. • seen primarily on the lateral aspects of the upper arms and thighs and the cheeks in children. • A small rim of erythema surrounds the involved hair follicles. Ichthyosis vulgaris • Up to 50% of AD patients have this autosomal dominant disorder • characterized by excessive scaling, which spares the flexures Dennie–Morgan lines • symmetric, prominent fold (single or double) beneath the margin of the lower eyelid. • originates in or near the inner canthus and extends to one-half to two-thirds of the lower lid . • Periorbital edema and lichenification or darkening under the eyes (‘allergic shiners’) may seen. Palmoplantar hyperlinearity • Increased prominence of palmar and plantar creases may be seen in AD patients, particular those with associated ichthyosis vulgaris Pityriasis alba • Infants and children with AD may have patches of hypopigmentation with fine scale, most commonly on the face. Such lesions are more noticeable in darkly pigmented children Cheilitis • Dry, crusty, ‘chapped’ lips or fissuring of the commisures (angular cheilitis) is more common in infants and children with AD than in adults Lichenification • results from repeated rubbing and scratching • the skin becomes thickened and leathery with exaggerated skin markings. • Early dermatologists called AD an ‘itch that rashes’, referring to the cutaneous changes that result from chronic rubbing and scratching. Prurigo nodularis • Multiple intensely and pruritic nodules occurring chiefly on the extremities (especially the anterior surfaces of the thighs and legs) COMPLICATIONS Secondary infection with S. aureus herpes simplex virus (eczema herpeticum). Rarely • • • • keratoconus cataracts Keratoconjunctivitis with secondary herpetic infection and corneal ulcers. DIAGNOSIS Diagnostic fatures of atopic dermatitis by the American Academy of Dermatology (AAD) Essential features (must present) Important features (support) Associated features (helpful, less specific) Essential features (must present) Pruritus Eczematous changes • Typical morphology and age-specific distribution patterns: • Facial, neck and extensor involvement in infants and children • Current or prior flexural lesions in any age group • Sparing of groin and axillary regions Chronic or relapsing course Important features (support) Early age of onset Personal and/or family history of atopy (IgE reactivity) Xerosis Associated features (helpful, less specific) Keratosis pilaris/ichthyosis vulgaris/palmar hyperlinearity Atypical vascular responses Perifollicular accentuation/lichenification/prurigo Ocular/periorbital changes Perioral/periauricular lesions The UK refinement diagnostic criteria for atopic dermatitis In order to qualify as a case of atopic dermatitis with the UK diagnostic criteria, the child must have: • An itchy skin condition (or parental report of scratching or rubbing in a child) • Plus three or more of the following: 1. Onset below age 2 years 2. History of skin crease involvement 3. History of a generally dry skin 4. Personal history of other atopic disease 5. Visible flexural dermatitis (or dermatitis of cheeks/forehead and outer limbs in children under 4 years) PATHOLOGY ‘Acute’AD. Spongiosis in the epidermis producing intraepidermal vesicles with exocytosis of lymphocytes ‘Chronic’AD. There is less spongiosis, with more irregular epidermal hyperplasia. DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS Nummular eczema dermatophytosis, Early stages of mycosis fungoides. ICD ACD PSORAIASIS SEBORREHIC DERMATITS TREATMENT Primary Prevention • Allergen avoidance during pregnancy, infancy, or both. Such investigations have typically focused on dietary allergens (particularly cow’s milk and eggs) and dust mites. • breastfeeding (which is thought to have immunomodulatory effects) and the reduce development AD but (especially in a family history of atopy) to suggestion of a higher risk of AD with a longer duration of breastfeeding. Supportive Care 1) After the onset of AD, a reduction of trigger factors 2) Hydration a specific Foaming detergents and soaps should be avoided. The regular use of emollients protect against inflammation provoked by irritants such as detergent, and increase the benefit obtained from topical corticosteroid therapy. Ceramide-rich emollients may lead to improvements in childhood atopic dermatitis through barrier repair mechanism Management of acute AD 1) Wet dressings and topical glucocorticoids; topical antibiotics (mupirocin ointment) 2) Hydroxyzine, 10–100 mg four times daily for pruritus. 3) Oral antibiotics (dicloxacillin, erythromycin) to eliminate S. aureus and treat MRSA according to sensitivity as shown by culture. Management of chronic AD TOPICAL SYSTEMIC PHOTOTHERAPY ADVANCED TTT TOPICAL Emollients Topical steroids topical calcineurin inhibitors (TCIs) Emollients Individually adapted emollients containing urea (4% in children; up to 10% in adults) should be used to support the skin barrier function and allow hydration of the skin. Topical steroids Principles of treatment with topical corticosteroids. Use the weakest steroid that controls the eczema effectively Review their use regularly; check for local and systemic side-effects In primary care, avoid using potent and very potent steroids for children with atopic eczema Be wary of repeat prescriptions Topical calcineurin inhibitors (TCIs) Tacrolimus and Pimecrolimus, are gradually replacing glucocorticoids in most patients. potently suppress itching and inflammatio n and do not lead to skin atrophy. not effective enough to suppress acute flares but work very well in minor flares and subacute atopic dermatitis. Strategy for topical treatment SYSTEMIC ANTI- HISTAMINIC SYSTEMIC GLUCOCORTICOIDS ANTIMICROBIALS ANTI- HISTAMINIC SEDATING ANTIHISTAMINES are helpful in breaking the ‘itch–scratch cycle’ in AD, given at bedtime. useful to patients in whom itching prevents sleep or in those scratch to producing hemorrhagic crusts at night. NON-SEDATING ANTIHISTAMINES are occasionally helpful, but the most benefit is usually obtained at higher doses SYSTEMIC GLUCOCORTICOIDS SHOULD BE AVOIDED EXCEPT in rare instances in adults for only short courses. For severe disease, prednisone, 60–80 mg daily for 2 days, then halving the dose each 2 days for the next 6 days. Patients tend to become dependent on oral glucocorticoid. Often, small doses (5–10 mg) make the difference in control and can be reduced gradually to even 2.5 mg/d, as is used for the control of asthma. Intramuscular glucocorticoids are risky and should be avoided. ANTIMICROBIALS • Antimicrobials are important for AD patients with cutaneous infections. • antibiotics can directly improve AD by reducing bacterial products thought to exacerbate AD is less clear. • Antistaphylococcal therapy (e.g. cephalosporins) can significantly improve superinfected AD and may provide some benefit to non-infected skin. • Ketoconazole has been used for head- or neckbased AD, presumably to reduce Malassezia colonization PHOTOTHERAPY Improve AD, but some patients cannot tolerate the heat generated by the equipment. UVB, UVA, narrowband UVB, combined UVA and UVB, and (PUVA) have all been effective in AD. Some patients benefit from natural sunlight. Has a favorable side-effect profile compared to systemic immunosuppressive agents, with potential risks of ‘sunburn’ and, with longterm treatment, photoaging and cutaneous malignancies. Advanced Therapies For the unusually difficult-to-manage AD patient CYCLOSPORINE METHOTREXATE AZATHIOPRINE BIOLOGICS CYCLOSPORINE Oral cyclosporine at a dose of 1.25 mg/kg per day is effective in reducing disease extent and severity as well as improving pruritus, sleep and quality of life in AD. renal toxicity after as little as 3–6 months of therapy limit the use of cyclosporine, but shortterm courses followed by maintenance therapy can be prescribed METHOTREXATE MTX is the folic antagonist aminopterin causes a temporary inhibition of keratinocyte proliferation during the first 24 hours after a therapeutic dose, and has an inhibtory effect on circulating and cutaneous lymphocytes Methotrexate 2.5–25 mg per week (depending upon patient age,weight and renal function) AZATHIOPRINE Azathioprine is an immunosuppressant drug effective in severe AD. Side effects are high, including myelo-suppression, hepatotoxicity, gastrointestinal disturbances, increased susceptibility for infections, and possible development of skin cancer. azathioprine is metabolized by the thiopurine methyl-transferase (TPMT); a deficiency of this enzyme should be excluded before starting azathioprine treatment. Dosage (2–3.5 mg/kg/day if normal, 0.5–1 mg/ kg/day if low) BIOLOGICS • Anti-IgE (omalizumab), which is approved for asthma, has been tried with variable results in AD. • Since these patients usually display very high levels of IgE, neutralizing these levels would require extremely high amounts of this biologic. • Nevertheless, some recent case report suggested the successful of omalizumab in selected patients • However, effects of biologics may be serious and need further evaluation. OUR MESSAGE AD IS A COMMON WELL KNOWN DISEASE BUT NEED TO BE CARFULLY DIAGNOSED SYSTEMIC STEROID IS NOT INDICATED IN TEARTMENT OF AD WHER AS EMOLLIENT ARE THE 1ST LINE