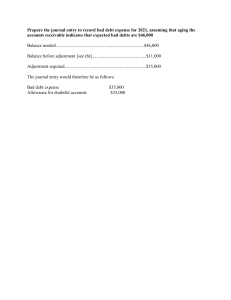

Depreciation: Depreciation is the acquisition cost of an asset (less the expected salvage value) spread over the economic life of that asset. The purpose of charging depreciation over the economic life of the asset is to match the cost of the asset over the period for which revenue is earned by using the asset. There are two methods of recording depreciation. Under the first method, the asset account is directly credited for the depreciation and the written down value is readily ascertained. The journal entry to record depreciation under the method is Depreciation A/c Dr. To Asset A/c Under the second method, the depreciation charged is credited to a depreciation provision a/c and the written down value of the asset is shown in the balance sheet by deducting the provision from the original cost of the asset. The journal entry recorded under this method is Depreciation A/c Dr. To Depreciation Provision A/c Balance in Depreciation is transferred to Profit and Loss A/c. The accounting entry is as under: Profit and Loss A/c Dr. To Depreciation A/c Depreciation provision account, if opened, will be shown by way of deduction from the relevant asset a/c in the balance sheet. How to write off a fixed asset A fixed asset is written off when if the asset is sold off or otherwise disposed of. A write off involves removing all traces of the fixed asset from the balance sheet, so that the related fixed asset account and accumulated depreciation account are reduced. There are two scenarios under which a fixed asset may be written off. The first situation arises when you are eliminating a fixed asset without receiving any payment in return. This is a common situation when a fixed asset is being scrapped because it is obsolete or no longer in use, and there is no resale market for it. In this case, Adjusting Entry for Depreciation Expense When a fixed asset is acquired by a company, it is recorded at cost (generally, cost is equal to the purchase price of the asset). This cost is recognized as an asset and not expense. The cost is to be allocated as expense to the periods in which the asset is used. This is done by recording depreciation expense. There are two types of depreciation – physical and functional depreciation. Physical depreciation results from wear and tear due to frequent use and/or exposure to elements like rain, sun and wind. Functional or economic depreciation happens when an asset becomes inadequate for its purpose or becomes obsolete. In this case, the asset decreases in value even without any physical deterioration. Understanding the Concept of Depreciation There are several methods in depreciating fixed assets. The most common and simplest is The straight-line depreciation method. Under the straight line method, the cost of the fixed asset is distributed evenly over the life of the asset. For example, ABC Company acquired a delivery van for $40,000 at the beginning of 2012. Assume that the van can be used for 5 years. The entire amount of $40,000 shall be distributed over five years, hence a depreciation expense of $8,000 each year. Straight-line depreciation expense is computed using this formula: Depreciable Cost – Residual Value Estimated Useful Life Depreciable Cost: Historical or un-depreciated cost of the fixed asset Residual Value or Scrap Value: Estimated value of the fixed asset at the end of its useful life Useful Life: Amount of time the fixed asset can be used (in months or years) In the above example, there is no residual value. Depreciation expense is computed as: = $40,000 – $0 5 years = $8,000 / year With Residual Value What if the delivery van has an estimated residual value of $10,000? The depreciation expense then would be computed as: = $40,000 – $10,000 5 years = $30,000 5 years = $6,000 / year Journal Entry for the Fixed Asset: When a fixed asset is added, the applicable fixed asset account is debited and accounts payable is credited. How to Record Depreciation Expense Depreciation is recorded at expense account by This is recorded at the end of the period (usually, at the end of every month, quarter, or year). The entry to record the $6,000 depreciation every year would be: Dec 31 Depreciation A/c -Van 6,000.00 Accumulated Depreciation 6,000.00 Depreciation Expense: An expense account; hence, it is presented in the income statement. It is measured from period to period. In the illustration above, the depreciation expense is $6,000 for 2012, $6,000 for 2013, $6,000 for 2014, etc. Accumulated Depreciation: A balance sheet account that represents the accumulated balance of depreciation. Accumulated Depreciation is credited when Depreciation Expense is debited in each accounting period. It is continually measured; hence the accumulated depreciation balance is $6,000 at the end of 2012, $12,000 in 2013, $18,000 in 2014, $24,000 in 2015, and $30,000 in 2016. Accumulated depreciation is a contra-asset account. It is presented in the balance sheet as a deduction to the related fixed asset. Here's a table illustrating the computation of the carrying value of the delivery van. 2012 Delivery Van - Historical Cost 2014 2015 2016 $40,000 $40,000 $40,000 $40,000 $40,000 Less: Accumulated Depreciation Delivery Van - Carrying Value 2013 6,000 12,000 18,000 24,000 30,000 $34,000 $28,000 $22,000 $16,000 $10,000 Notice that at the end of the useful life of the asset, the carrying value is equal to the residual value. Depreciation for Acquisitions Made Within the Period The delivery van in the example above has been acquired at the beginning of 2012, i.e. January. Therefore, it is easy to calculate for the annual straight-line depreciation. But what if the delivery van was acquired on April 1, 2012? In this case we cannot apply the entire annual depreciation in the year 2012 because the van has been used only for 9 months (April to December). We need to prorate. For 2012, the depreciation expense would be: $6,000 x 9/12 = $4,500. Years 2013 to 2016 will have $6,000 annual depreciation expense. In 2017, the van will be used for 3 months only (January to March) since it has a useful life of 5 years (i.e. April 1, 2012 to March 31, 2017). The depreciation expense for 2017 would be: $6,000 x 3/12 = $1,500, and thus completing the accumulated depreciation of $30,000. 2012 (April to December) $ 4,500 2013 (entire year) 6,000 2014 (entire year) 6,000 2015 (entire year) 6,000 2016 (entire year) 6,000 2017 (January to March) Total for 5 years 1,500 $ 30,000 Accounting for Bad Debts While making sales on credit, the company is well aware that not all of its debtors will pay in full and the company has to encounter some losses called bad debts. Bad debts expenses can be recorded using two methods viz. 1.) Direct write-off method and 2.) Allowance method. #1 – Direct Write-Off Method Bad debts are recorded as a direct loss from defaulters, writing off their accounts and transferred in full amount to P&L account, thus lowers your net profit. E.g. Mr. Unreal passed away and will not be able to make any payment. #2 – Allowance Method Charge the reverse value of accounts receivables for doubtful customers to a contra account called allowance for doubtful account. This keeps the P&L account unaffected from bad debts and reporting of the direct loss against revenues can be avoided. However writing-off the account at a future date is possible. For example:a) Mr. Unreal incurred losses and is not able to make payment at due dates. b) Mr. Unreal goes bankrupted and will not pay at all. c) Mr. Unreal has recovered from initial losses and wants to pay all of its previous debts. Adjusting Entry for Bad Debts Expense Companies provide services or sell goods for cash or on credit. Allowing credit tends to encourage more sales. However, businesses that allow credit are faced with the risk that their receivables may not be collected. Accounts receivable should be presented in the balance sheet at net realizable value, i.e. the most probable amount that the company will be able to collect. Net realizable value for accounts receivable is computed like this: Accounts Receivable (Gross Amount) Less: Allowance for Bad Debts Accounts Receivable (Net Realizable Value) $100,000 3,000 $ 97,000 Allowance for Bad Debts (also often called Allowance for Doubtful Accounts) represents the estimated portion of the Accounts Receivable that the company will not be able to collect. Take note that this amount is an estimate. There are several methods in estimating doubtful accounts.The estimates are often based on the company's past experiences. To recognize doubtful accounts or bad debts, an adjusting entry must be made at the end of the period. The adjusting entry for bad debts looks like this: Dec 31 Bad Debts Expense Allowance for Bad Debts xxx.xx xxx.xx Bad Debts Expense a.k.a. Doubtful Accounts Expense: An expense account; hence, it is presented in the income statement. It represents the estimated uncollectible amount for credit sales/revenues made during the period. Allowance for Bad Debts a.k.a. Allowance for Doubtful Accounts: A balance sheet account that represents the total estimated amount that the company will not be able to collect from its total Accounts Receivable. What is the difference between Bad Debts Expense and Allowance for Bad Debts? Bad Debts Expense is an income statement account while the latter is a balance sheet account. Bad Debts Expense represents the uncollectible amount for credit sales made during the period. Allowance for Bad Debts, on the other hand, is the uncollectible portion of the entire Accounts Receivable. You can also use Doubtful Accounts Expense and Allowance for Doubtful Accounts in lieu of Bad Debts Expense and Allowance for Bad Debts. However, it is a good practice to use a uniform pair. Some say that Bad Debts have a higher degree of uncollectibility that Doubtful Accounts. In actual practice, however, the distinction is not really significant. Here's an Example Gray Electronic Repair Services estimates that $100.00 of its credit revenue for the period will not be collected. The entry at the end of the period would be: Dec 31 Bad Debts Expense 100.00 Allowance for Bad Debts 100.00 Again, you may use Doubtful Accounts. Just be sure to use a logical (and uniform) pair every time. For example: Dec 31 Doubtful Accounts Expense 100.00 Allowance for Doubtful Accounts 100.00 If the company's Accounts Receivable amounts to $3,400 and its Allowance for Bad Debts is $100, then the Accounts Receivable shall be presented in the balance sheet at $3,300 – the net realizable value. Accounts Receivable (Gross Amount) Less: Allowance for Bad Debts Accounts Receivable - Net Realizable Value $ 3,400 100 $ 3,300 Reverse any accumulated depreciation and Reverse the original asset cost. If the asset is fully depreciated, that is the extent of the entry. For example, ABC Corporation buys a machine for $100,000 and recognizes $10,000 of depreciation per year over the following ten years. At that time, the machine is not only fully depreciated, but also ready for the scrap heap. ABC gives away the machine for free and records the following entry. Debit Accumulated depreciation 100,000 Credit Machine asset 100,000 A variation on this first situation is to write off a fixed asset that has not yet been completely depreciated. In this situation, write off the remaining undepreciated amount of the asset to a loss account. To use the same example, ABC Corporation gives away the machine after eight years, when it has not yet depreciated $20,000 of the asset's original $100,000 cost. In this case, ABC records the following entry: Debit Loss on asset disposal 20,000 Accumulated depreciation 80,000 Machine asset Credit 100,000 The second scenario arises when you sell an asset, so that you receive cash (or some other asset) in exchange for the fixed asset you are selling. Depending upon the price paid and the remaining amount of depreciation that has not yet been charged to expense, this can result in either a gain or a loss on sale of the asset. For example, ABC Corporation still disposes of its $100,000 machine, but does so after seven years, and sells it for $35,000 in cash. In this case, it has already recorded $70,000 of depreciation expense. The entry is: Debit Credit Cash 35,000 Accumulated depreciation 70,000 Gain on asset disposal 5,000 Machine asset 100,000 What if ABC Corporation had sold the machine for $25,000 instead of $35,000? Then there would be a loss of $5,000 on the sale. The entry would be: Debit Cash 25,000 Accumulated depreciation 70,000 Loss on asset disposal Machine asset Credit 5,000 100,000 A fixed asset write off transaction should only be recorded after written authorization concerning the targeted asset has been secured. This approval should come from the manager responsible for the asset, and sometimes also the chief financial officer. Fixed asset write offs should be recorded as soon after the disposal of an asset as possible. Otherwise, the balance sheet will be overburdened with assets and accumulated depreciation that are no longer relevant. Also, if an asset is not written off, it is possible that depreciation will continue to be recognized, even though there is no asset remaining. To ensure a timely write off, include this step in the monthly closing procedure. Salary Expense Reversing entries are optional accounting procedures which may sometimes prove useful in simplifying record keeping. A reversing entry is a journal entry to “undo” an adjusting entry. Consider the following alternative sets of entries. The first example does not utilize reversing entries. An adjusting entry was made to record $2,000 of accrued salaries at the end of 20X3. The next payday occurred on January 15, 20X4, when $5,000 was paid to employees. The entry on that date required a debit to Salaries Payable (for the $2,000 accrued at the end of 20X3) and Salaries Expense (for $3,000 earned by employees during 20X4). The next example revisits the same facts using reversing entries. The adjusting entry in 20X3 to record $2,000 of accrued salaries is the same. However, the first journal entry of 20X4 simply reverses the adjusting entry. On the following payday, January 15, 20X5, the entire payment of $5,000 is recorded as expense. Illustration Without Reversing Entries Illustration With Reversing Entries The net impact with reversing entries still records the correct amount of salary expense for 20X4 ($2,000 credit and $5,000 debit, produces the correct $3,000 net debit to Salaries Expense). It may seem odd to credit an expense account on January 1, because, by itself, it makes no sense. The credit only makes sense when coupled with the subsequent debit on January 15. Notice from the following diagram that both approaches produce the same final results: BY COMPARING THE ACCOUNTS AND AMOUNTS, NOTICE THAT THE SAME END RESULT IS PRODUCED! In practice, reversing entries will simplify the accounting process. For example, on the first payday following the reversing entry, a “normal” journal entry can be made to record the full amount of salaries paid as expense. This eliminates the need to give special consideration to the impact of any prior adjusting entry. Reversing entries would ordinarily be appropriate for those adjusting entries that involve the recording of accrued revenues and expenses; specifically, those that involve future cash flows. Importantly, whether reversing entries are used or not, the same result is achieved! Wages It might be helpful to look at the accounting for both situations to see how difficult bookkeeping can be without recording the reversing entries. Let’s look at let’s go back to your accounting cycle example of Paul’s Guitar Shop. In December, Paul accrued $250 of wages payable for the half of his employee’s pay period that was in December but wasn’t paid until January. This end of the year adjusting journal entry looked like this: Accounting with the reversing entry: Paul can reverse this wages accrual entry by debiting the wages payable account and crediting the wages expense account. This effectively cancels out the previous entry. But wait, didn’t we zero out the wages expense account in last year’s closing entries? Yes, we did. This reversing entry actually puts a negative balance in the expense. You’ll see why in a second. On January 7th, Paul pays his employee $500 for the two week pay period. Paul can then record the payment by debiting the wages expense account for $500 and crediting the cash account for the same amount. Since the expense account had a negative balance of $250 in it from our reversing entry, the $500 payment entry will bring the balance up to positive $250– in other words, the half of the wages that were incurred in January. See how easy that is? Once the reversing entry is made, you can simply record the payment entry just like any other payment entry. Accounting without the reversing entry: If Paul does not reverse last year’s accrual, he must keep track of the adjusting journal entry when it comes time to make his payments. Since half of the wages were expensed in December, Paul should only expense half of them in January. On January 7th, Paul pays his employee $500 for the two week pay period. He would debit wages expense for $250, debit wages payable for $250, and credit cash for $500. The net effect of both journal entries have the same overall effect. Cash is decreased by $250. Wages payable is zeroed out and wages expense is increased by $250. Making the reversing entry at the beginning of the period just allows the accountant to forget about the adjusting journal entries made in the prior year and go on accounting for the current year like normal. As you can see from the T-Accounts above, both accounting method result in the same balances. The left set of T-Accounts are the accounting entries made with the reversing entry and the right T-Accounts are the entries made without the reversing entry. Provision for Bad Debts, Cash Discounts Payable and Cash Discounts Receivable: Bad Debts: The sales revenue recorded in the books of accounts of an organisation represent the amount realized or to be realized from the sale of goods. When goods are sold on credit it may sometimes happen that even though customers bought them with every intention of paying for them, due to certain subsequent change in circumstances, they may not be able to fulfill their obligations. For instance, if a customer, subsequent to the date of credit sales, is adjusted an insolvent and his estate cannot pay anything towards satisfaction of the amount due from him, then logically, the entry passed at the time of sale should be removed by reversing it, as the situation is similar to the sale not having taken place. In practice, however, instead of reversing the previous entry, the amount which cannot be recovered is considered as a loss called ‘Bad debts’. Example: ABC Ltd., had debtors outstanding to the extent of Rs. 7,50,000/- as on 31st March, 2013 Mr. X, who owed Rs. 15,000/- to the company has been adjudged insolvent and his estate is unable to pay anything. The journal entry to record the above loss would be: Bad debts A/c Dr. 15,000/To X A/c Cr. 15,000/Note that the sales account remains unchanged. However, in the income statement, while sales revenue will appear at the full figure, the bad debts will appear as a loss and thus the reduction in the amount realised will be accounted for. The Accounts Receivable account will also appear in the Balance Sheet at the realisable value of Rs. 7, 35,000. The journal entry for recording bad debts is: Bad Debts A/c Dr. To Accounts Receivable A/c Provision for Bad and Doubtful Debts: We have already seen that according to the realisation concept, the amount to be recognised as revenue is the amount that is reasonably certain to be realised. When there is a possibility that all the sales revenue may not be realised in the future due to occurrence of bad debts, the sales revenue, then, in the income statement should reflect this position. However, in practice, the sales revenue is shown as the gross figure and any possible loss due to bad debts is shown as an expense. When bad debts are expected to occur in the future: (a) The exact amount of loss may not be known and (b) A particular debtor’s account cannot be identified to write off the expected loss or even if the debtor’s account can be identified, a reduction in claim can be given effect to only when it becomes certain. To circumvent these problems, usually, a provision is made for the expected bad debts loss out of profits of the current year. This reduces the profit and hence the income statement conforms to the realisation principle and also prevents an estimated portion of profits from being distributed to the proprietors. For creating the provision for bad and doubtful debts, the journal entry is, Profit and Loss A/c Dr. To Provision for Bad Debts A/c. Example: The Accounts Receivable of PQR Ltd. was Rs. 1, 50,000/- as on 31st March, 2012. It was estimated that Rs. 5,000/- of the amount due may turn out to be uncollectable during the forthcoming year. For creation of the provision the journal entry will be, Profit and Loss A/c Dr. 5,000/To Provision for Bad Debts A/c 5,000/While the amount of the possible loss will appear on the debit side of the profit and loss account, the provision created, though a liability will be shown as a deduction from Accounts Receivable on the asset side of balance sheet. This would ensure that the current asset is shown at the realizable value. Estimating Bad and Doubtful Debts: Any one of the following methods may be used to estimate the amount of possible bad debts: 1. Bad debts may be estimated as a percentage of total sales during the year. This method can be used only when there are no cash sales or such sales are negligible. 2. Bad debts may be estimated as a percentage of credit sales. 3. Estimate bad debts as a percentage of receivable outstanding at the end of the accounting period. The percentage used will be based on the judgment of the management and the past experience with regard to bad debts. Another logical way to estimate bad debts would be to draw up an aging schedule for the outstanding debtors and apply different percentages for amounts outstanding for various lengths of time. Treatment of Bad Debts when a Provision for Bad Debts Exists: Let us extend the example of PQR Ltd., to the financial year ending 31st March, 2012. The following details are available: Bad Debts during the year Rs. 3,500 Accounts Receivable as on 31.3.2012 Rs. 1, 70,000/PQR Ltd., would like to maintain the provision at 5% of Sundry Debtors. The Accounts Receivable of Rs. 1,70,000/- as on 31/3/2012 is after account for the bad debts of Rs. 3,500/-. When bad debts occurred, the following entry would have been passed: Bad Debts A/c Dr. 3,500/To Sundry Debtors A/c 3,500/Since provision for bad debts to the extent of Rs. 5,000/- already exists, the actual bad debts of Rs. 3,500/- will be transferred at the end of the year to this provision account and not to the profit and loss account. The entry for the transfer will be: Provision for the Bad Debts A/c Dr. Rs. 3,500 To Bad Debts A/c Rs. 3,500 At this point the provision A/c will appear as under: Since the provision has been utilised to the extent of Rs. 3,500/-, only Rs. 1,500/- is left for setting off any bad debts in the forthcoming year. However, PQR Ltd., wishes to maintain the provision at 5% on debtors. So, the balance required in the provision account as on 31.03.2012 is, 1, 70,000 x 5/100 = Rs. 8,500 To bring up the provision to the required balance a further appropriation of Rs. 7,000/- (Rs. 8,500/- – Rs. 1,500/-) will have to be made from the profits and loss account. Entry will be, Profit and Loss A/c Dr. 7,000.00 To Provision for Bad Debts A/c 7,000.00 The provision account after positing this entry will appear as follows: The balance sheet will again show the Accounts Receivable at their realisable value. We will extend the above example to yet another financial year. The following details are available for the year ending 31.3.2013 Bad Debts during the year 1,000.00 Sundry Debtors as on 31.3.2013 1, 10,000 PQR Ltd., would like to maintain the provision for bad debts as 5% of debtors. As in the previous year, the total bad debts will be transferred to the provision for bad debts. Provision for Bad Debts A/c Dr. 1,000.00 To Bed Debts A/c. 1,000.00 The provision account after the above transfer will appear as follows: The provision required on the closing debtors will be, (5 x 100) x 1, 10,000 = Rs. 5,500/The opening provision of Rs. 8,500/- has been utilised only to the extent of Rs. 1,000/- and therefore, Rs. 7,500/- is the amount available for further appropriation. Since the balance to be carried forward to the next accounting year is only Rs. 5,500/- a sum of Rs. 2,000/(7,500/- less 5,500/-) can be transferred back to Profit and Loss A/c as excess provision which is not required to be carried forward. So, to retain a balance of Rs. 5,500/- in the provision account, the journal entry will be, Provision for Bad Debts A/c Dr. 2,000.00 To Profit & Loss A/c 2,000.00 Recovery for Bad Debts Written Off: Sometimes, an amount written off as bad debts may be subsequently recovered. Any such recovery must be treated as a windfall and transferred to the profit and Loss A/c as a gain. The journal entries will be, At the time of receipt of the amount Bank A/c or Cash A/c Dr. To Bad Debts Recovered A/c At the end of the financial year, Bed Debts Recovered A/c Dr. To Profit and Loss A/c Provision for Discounts on Accounts Receivable: The organisations which allow the facility of making payments before the due date and enable their debtors to avail of cash discounts, must take into account the possible amount of discounts that may be allowed on closing debtors in the forthcoming year. This is necessary to show the closing debtors at their realisable value. The principles for creation and maintenance of the provisions for discounts on debtors are the same as those discussed in the section on provision for bad debts. The only additional point to be noted is that discounts will be estimated on debts considered goods i.e., closing sundry debtors minus provision for bad debts. The illustration given clearly explains the methods of maintaining a provision for discounts on debtors. The following details are available for M Limited: While the company maintains 5% provision for bad debts, it would like to maintain 3% provision for discounts beginning from 31.3.2011. The entries in the provision for discounts on receivable and the relevant extracts from the balance sheets are shown below: