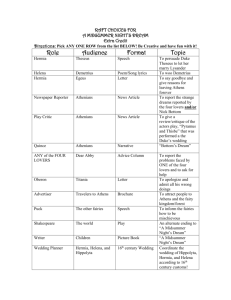

UT Midsummer Night’s Dream The University of Madison University Theatre A Midsummer Night’s Dream By William Shakespeare Mitchell Theatre, February 27 to March 14, 2009 Directed by Norma Saldivar Scenic Design by Aaron Kennedy Costume Design by Rachel Barnett Lighting Design by Matt Albrecht Sound Design by Ray Nardelli Stage Management by Marion Zennie Dramaturgy by Chris Morrison Study Guide By Chris Morrison 1 UT Midsummer Night’s Dream A Midsummer Night’s Dream Oberon, King of the Fairies, as sketched by costume designer Rachel Barnett. Find out much more and see many more images at http://midsummerdream.terapad.com/ 2 UT Midsummer Night’s Dream Director’s Notes A Midsummer Night’s Dream is surely one of the most often produced of Shakespeare’s plays and, clearly for theatre producers, one of the most accessible. Its popularity can be drawn from the distinctive characters that represent three unique worlds: those of the rarified world of nobility, ordinary workmen, and a fairy kingdom caught in a web of action. At the core of the play is the theatrical device of moving the story or action of the play and its characters from the court or society of men to the woods where non-human entities reign. In doing so, Shakespeare provides us with an outlet for change. He gives us the chance to witness the characters going through a lifealtering experience. With the understanding that in Midsummer Shakespeare offers the complexity of three societies with the social hierarchy and unique social structures, we have attempted to render this production in a non-traditional manner. We reveal the magic of this popular story by placing it in the early 1950s on an unspecified island in the Greater Antilles. The Greater Antilles We mine the rich tapestry of Caribbean culture for inspiration on all levels of the production. In placing the production in the Greater Antilles, we have tried to emphasize the universality of the playwright. Shakespeare’s extraordinary ability to express fundamental human nature transcends not only time but also transcends culture and race. We attempt to transpose the story into a world influenced by the ideas of the islands, not to literally transpose the play to any one particular island but rather to use the rich depth of culture to inform and articulate the play. Love is at the core of the story and love is not always logical or completely reasonable, so this play is not grounded in a literal world; it is dreamlike. And as such it is a mere reflection of a reality—recognizable but not always logical, beautiful but sometimes frightening and—hopefully--inspiring. Norma Saldivar 3 UT Midsummer Night’s Dream Plot Summary Act One of A Midsummer Night's Dream begins in Theseus’s Athenian Palace. Theseus the Duke is warmly contemplating his upcoming marriage to Hippolyta, a warrior queen he “captured” abroad. We soon meet two sets of young lovers: Lysander & Hermia, and Demetrius & Helena. However conflict has arisen because Hermia's father Egeus wants his daughter to marry Demetrius—Demetrius having recently fallen out of love with Helena. Hermia, loving Lysander, refuses, so Egeus calls upon Theseus to use the law to force Hermia to marry Demetrius. Theseus has no option but to tell Hermia she must choose among (a) her father’s choice of husband (b) death or (c) spending the rest of her life in a nunnery. Once alone, Hermia and Lysander decide to run away to the forest—beyond the bounds of Athenian law—and marry. They tell Helena of this and she decides to try to win back Demetrius’s favor by telling him of the elopement plan. Meanwhile in the same forest the King and Queen of the Fairies, Oberon and Titania, have fallen into dispute over an Indian orphan. Titania has the boy and Oberon seeks possession. They argue and part in bad odor. Oberon instructs Puck AKA Robin Goodfellow—a particularly adept minion—to fetch him a very special flower, the juice of which when applied to a sleeper’s eyes will make the victim fall in love with the first person (or animal) he or she sees on waking. Oberon hopes to apply this to Titania, thus humiliating her, and take the boy as his page. Both sets of mortal lovers (one set being “ex”) arrive in the forest separately. Demetrius, there to find Hermia and prevent her from marrying Lysander, is unpleasant to a “fawning” Helena. Oberon witnesses this, feels sorry for the young woman, and tells Puck to put some of the same love juice on Demetrius’s eyes so that he will once again love Helena. Puck mistakes Lysander for Demetrius so that when Lysander wakes and happens to see Helena he falls for her. As the drug is potent, he now vociferously rejects Hermia whom he was about to marry. Confusion, angst, and recriminations abound. Also in the same part of the (crowded) forest, a group of Athenian tradesmen have met to rehearse Pyramus and Thisbe—a rather silly Romeo and Juliet-like play concerning two lovers, a lion, and a talking wall—which they hope to present before the Duke during the upcoming nuptials. Puck magics a donkey’s head onto Bottom, the most bumptious of the actors, and Titania (with the love potion on her eyes) wakes up and falls for the now-monstrous Bottom. Oberon is delighted. However observing that Helena’s plight has not improved, he decides to remedy the situation and “juices” Demetrius’s eyes so that he too wakes and falls for Helena. Rather than solving the situation however, on finding herself the object of intense sexual rivalry between both Athenian men, Helena— prone to self-doubt—thinks she is the butt of a trick concocted by her companions. She and Hermia almost come to blows while the two men run off to fight it out. Trying to help the bickering mortals, Oberon has Puck separate the four and put them to sleep. Oberon administers an antidote to Lysander and Titania (but not to Demetrius who will probably pass the rest of his life under the influence of Cupid’s love juice). Oberon and Titania make peace and he gets the boy. Theseus and Hippolyta arrive in the forest to find the somewhat baffled lovers—now paired off to everyone’s satisfaction— waking from the strangest dreams. Finally at the wedding feast, which now embraces three couples, Pyramus and Thisbe is performed to everyone’s great amusement. A Midsummer Night’s Dream ends with general frivolity and fairy blessings. 4 UT Midsummer Night’s Dream The Caribbean Connection. (Movie and Video Clips) The Lost City (205) a movie by Andy Garcia starring Garcia, Dustin Hoffman, and Bill Murray. “In Havana, Cuba in the late 1950's, a wealthy family, one of whose sons is a prominent nightclub owner, is caught in the violent transition from the oppressive regime of Batista to the Marxist government of Fidel Castro. Castro's regime ultimately leads the nightclub owner to flee to New York.” Director Norma Saldivar suggests this movie as a good source of the ambiance of this production of A Midsummer Night’s Dream. Trailer for The Lost City http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xPZulsaHo8o Lost City Part 1 (the rest is on YouTube in parts): http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qY-_ilB39CY&feature=related YouTube clip concerning Cuban religious customs Virgen del caridad del cobre http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YPQ9G0-SINE&feature=related http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=w-hD7k0r7bE&NR=1 The Cuban Revolution (Warning! This has real firing squads) http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6IqFxcwWv2Q and http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wUPqsh52QPc&feature=related Cuban Revolution and local religion: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tJCFpBf9GiM&feature=related Music Any YouTube clip of the Buena Vista Social Club (A Cuban music group). For example: < http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6JEdf7XsV5g> And the song “Silencio” by Ibrahim Ferrar < http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NE1ijoIxMo0> 5 UT Midsummer Night’s Dream Character List Puck - Also known as Robin Goodfellow, Puck is Oberon’s jester, a mischievous fairy who delights in playing pranks on mortals. Though A Midsummer Night’s Dream divides its action between several groups of characters, Puck is the closest thing the play has to a protagonist. His enchanting, mischievous spirit pervades the atmosphere, and his antics are responsible for many of the complications that propel the other main plots: he mistakes the young Athenians, applying the love potion to Lysander instead of Demetrius, thereby causing chaos within the group of young lovers; he also transforms Bottom’s head into that of an ass. Oberon – (O-be-ron) The king of the fairies, Oberon is initially at odds with his wife, Titania, because she refuses to relinquish control of a young Indian prince whom he wants for a knight. Oberon’s desire for revenge on Titania leads him to send Puck to obtain the love-potion flower that creates so much of the play’s confusion and farce. Titania – (Tie-tan-ya) The beautiful queen of the fairies, Titania resists the attempts of her husband, Oberon, to make a knight of the young Indian prince that she has been given. Titania’s brief, potion-induced love for Nick Bottom, whose head Puck has transformed into that of an ass, yields the play’s foremost example of the contrast motif. Lysander – (Lie-san-der) A young man of Athens, in love with Hermia. Lysander’s relationship with Hermia invokes the theme of love’s difficulty: he cannot marry her openly because Egeus, her father, wishes her to wed Demetrius; when Lysander and Hermia run away into the forest, Lysander becomes the victim of misapplied magic and wakes up in love with Helena. Demetrius – (De-mee-tree-us) A young man of Athens, initially in love with Hermia and ultimately in love with Helena. Demetrius’s obstinate pursuit of Hermia throws love out of balance among the quartet of Athenian youths and precludes a symmetrical two-couple arrangement. Hermia – (Her-mee-a) Egeus’s daughter, a young woman of Athens. Hermia is in love with Lysander and is a childhood friend of Helena. As a result of the fairies’ mischief with Oberon’s love potion, both Lysander and Demetrius suddenly fall in love with Helena. Self-conscious about her short stature, Hermia suspects that Helena has wooed the men with her height. By morning, however, Puck has sorted matters out with the love potion, and Lysander’s love for Hermia is restored. Helena – (He-len-a) A young woman of Athens, in love with Demetrius. Demetrius and Helena were once betrothed, but when Demetrius met Helena’s friend Hermia, he fell in love with her and abandoned Helena. Lacking confidence in her looks, Helena thinks that Demetrius and Lysander are mocking her when the fairies’ mischief causes them to fall in love with her. 6 UT Midsummer Night’s Dream Egeus – (Ee-gee-us) Hermia’s father, who brings a complaint against his daughter to Theseus: Egeus has given Demetrius permission to marry Hermia, but Hermia, in love with Lysander, refuses to marry Demetrius. Egeus’s severe insistence that Hermia either respect his wishes or be held accountable to Athenian law places him squarely outside the whimsical dream realm of the forest. Theseus – (Thee-see-us) The heroic duke of Athens, engaged to Hippolyta. Theseus represents power and order throughout the play. He appears only at the beginning and end of the story, removed from the dreamlike events of the forest. Hippolyta – (He-paw-le-ta) The legendary queen of the Amazons, engaged to Theseus. Like Theseus, she symbolizes order. Nick Bottom - The overconfident weaver chosen to play Pyramus in the craftsmen’s play for Theseus’s marriage celebration. Bottom is full of advice and self-confidence but frequently makes silly mistakes and misuses language. His simultaneous nonchalance about the beautiful Titania’s sudden love for him and unawareness of the fact that Puck has transformed his head into that of an ass mark the pinnacle of his foolish arrogance. Peter Quince - A carpenter and the nominal leader of the craftsmen’s attempt to put on a play for Theseus’s marriage celebration. Quince is often shoved aside by the abundantly confident Bottom. During the craftsmen’s play, Quince plays the Prologue. Francis Flute - The bellows-mender chosen to play Thisbe in the craftsmen’s play for Theseus’s marriage celebration. Forced to play a young girl in love, the bearded craftsman determines to speak his lines in a high, squeaky voice. Robin Starveling - The tailor chosen to play Thisbe’s mother in the craftsmen’s play for Theseus’s marriage celebration. He ends up playing the part of Moonshine. Tom Snout - The tinker chosen to play Pyramus’s father in the craftsmen’s play for Theseus’s marriage celebration. He ends up playing the part of Wall, dividing the two lovers. Snug - The joiner chosen to play the lion in the craftsmen’s play for Theseus’s marriage celebration. Snug worries that his roaring will frighten the ladies in the audience. Philostrate – (Fi-lo-strate) Theseus’s Master of the Revels, responsible for organizing the entertainment for the duke’s marriage celebration. Peaseblossom, Cobweb, Moth, and Mustardseed - The fairies ordered by Titania to attend to Bottom after she falls in love with him. (These notes taken from Sparknotes: < http://www.sparknotes.com/shakespeare/msnd/characters.html>) 7 UT Midsummer Night’s Dream A Production History Four Centuries of Staging Shakespeare’s Dream Were a twenty-first-century playwright to write a new work featuring (a) a onebreasted queen from a country called “Feminy,” (b) a Greek mythic hero who has just captured—and now wishes to marry—this fierce woman, (c) a tragic love story set in Baghdad featuring an apologetic lion and a talking wall, (d) a gang of bumbling artisans from rural sixteenth-century England, (e) blind Cupid, a misfired arrow, and a “wounded” flower, (f) a couple of Indian bystanders—one dead, the other kidnapped— twit in a donkey’s head, the playwright might face stern questions as to the state of his or her sanity. Blend in a knot of young lovers who spend much of their time scrambling through a moonlit forest like madmen on magic mushrooms and one can’t help sensing an overstretching of the already elastic bounds of postmodernist art. Yet over four hundred years ago these were exactly the grab-bag of sources and situations that Shakespeare folded into his masterful and ever-fascinating A Midsummer Night’s Dream. To enjoy the play, we the audience need not know that Hippolyta may have severed her own breast, or that, had she won the battle with Theseus, he might have faced a swift beheading. It is of little moment to us that the “merry and tragical” tale of Pyramus and Thisbe supposedly originated in Mesopotamia or that Oberon’s name has affinities to the dwarf Alberich in Wagner’s Ring Cycle. We need only enjoy the end result as staged. And down the centuries, the complexity, range, and sheer imaginativeness of this comedy’s ingredients have stimulated some of the most culturally diverse, innovative, and visually stunning productions of all among the Shakespearian canon. Written sometime in 1594-6 when Shakespeare, just turned thirty, had completed about one third of his oeuvre and had yet to tackle his great tragedies, for almost two centuries now scholars have sought to place Queen Elizabeth I (reigned 1558-1603) at the first performance. What cozier picture of a supposedly Golden Age of Elizabethan harmony can one invoke than a heady divertissement penned to celebrate the highest of high society weddings? Surrounded by loyal courtiers, the beloved Queen blushes at flattering references to a “fair vestal” and imperial votress [nun],” and smiles knowingly at Shakespeare’s gentle mockery of her nation’s cack-handed bumpkins and love-drugged gentry. Indeed, in hopes of tying a set of nuptials into historical matrimony with the play—in search of a “dream” Dream—the records of at least eleven likely weddings have been minutely examined. All to no avail; it is now thought unlikely that Elizabeth attended the opening performance or that the play was written for any marriage. Queen Elizabeth 1 8 UT Midsummer Night’s Dream By the early part of the eighteenth century, the rise of the British merchant class led to a desire that plays carry a strong moral message. For example, a visit to George Lillo’s The London Merchant (1731), which warns of the terrible fate awaiting those who stray from the path of purity, honesty, and loyalty, became for over three decades an annual pilgrimage for London’s apprentices. A Midsummer Night’s Dream, by contrast, failed to provide any such heavy-handed example. By then critics had come to consider the play “wild and fantastical” (Samuel Johnson), or—the chronology being misunderstood—the early jottings of an “unripe” genius. Other than the relative value of patrimony and stable marriage over mad fumblings in a bewitched forest, what lesson could a wealthy merchant draw from the play? “Young apprentices! When falling asleep in a forest, keep an eye out for love potion-carrying fairies!” Or “Fairies! Remember, when applying a love potion to a sleeping Athenian, make sure to check his identity first!”?? Hogarth's The Rake's Progress "In the Madhouse" (1735). By the time Queen Victoria assumed the throne in 1837, Britain had firmly embraced its identity as a mighty empire. But what connection could an Athenian court comedy have to the vast network of dominions, colonies, protectorates, mere mandates, and more that stretched across the globe? The answer lies in the figure of Theseus. He may do little more than bookend Midsummer’s madness with cool, patrician rationality, but by the beginning of the nineteenth century this “Greek argonaut” had risen to considerable significance within European culture. “The figure of Theseus loomed large in romantic art and literature’s constructions of the ancient world. Within the general enthusiasm for the Hellenic world … we find [him] refigured in poetry and statuary as a paradigmatic protector of civilization over barbarism” (Williams 80). The English had begun to take their own Greek heritage seriously after their famous defeat of Napoleon at Waterloo (1815). Then adoration of all things Hellenic burst into florescence in the brouhaha surrounding marble statuary that Lord Elgin, an English diplomat, “removed”—AKA “stole”—from the Parthenon and put on display in England. A central figure in the Elgin marbles was (mistakenly) thought to represent Theseus. In 1816 when these magnificent sculptures found a home at the British Museum, Frederick Reynolds took advantage of the confluence of events and rounded off his A Midsummer Night’s Dream opera with: A GRAND PAGENT, commemorative of The Triumphs of Theseus Over the Cretans—the Thebans—the Amazons—the Centaurs—the Minotaur. 9 UT Midsummer Night’s Dream Ariadne in the Labyrinth—the Mysterious Peplum, or Veil of Minerva— the Ship Argo—and the Golden Fleece. Reynolds sought to compare a wildly aggrandized Theseus with a seemingly invincible British Empire. From then on there was no looking back for A Midsummer Night’s Dream. The Elgin Marbles: The figure in the center was thought to be Thesius . The identification of Ancient Greece with the Great British Empire, advances in scenery and lighting technology, and even the return of a strong woman to the British throne led to the beginning of a Golden Age for this long-neglected play. Women in particular made much of this opportunity. Lucia Elizabeth Vestris’s 1840 London production offered more of the text than had been performed in over two hundred years. And in assigning herself the role of Oberon, King of the Fairies, Vestris—by all accounts a beautiful woman with an enthusiastic male following—set a cross-dressing example that was followed by all but one major English and American production until 1914. Lucia Elizabeth Vestris in The Alcaid, c.1835. It was the actor-manager Sir Herbert Beerbohm Tree (1852-1917) who first brought live rabbits to the much-trampled forest outside Athens. His 1900 production of Midsummer at Her Majesty’s Theatre, London can be considered “a kind of victory lap” for Victorian Shakespearian staging. Enormously popular (seen by 220,000), this 10 UT Midsummer Night’s Dream production was sentimental, highly pictorial, monumentalized, and embellished with novelties to the nth degree. Electric lights had now made it to the breastplate and crown of Oberon, played by a woman whose spiky crown instantly evoked Britannia, the personification of British nationalism. And yet these “comforting images of England as Theseus’s Athens, source of civilization” (Williams 132) had a hollow ring; just before the premiere Britain had experienced “Black Week” when its armies suffered several defeats in South Africa. The beginning of the end of the British Empire was nigh. (Rabbits roamed the stage in Beerbohm Tree's 1911 MSND.) And—bran-munching bunnies aside (one bit Bottom)—the beginning of the end of Victorian over-elaborate, pictorial stagings of A Midsummer Night’s Dream was also nigh. In 1914 a radically modern production opened in London’s Savoy Theatre. Harley Granville Barker (1877-1946) worshipped only one theatrical deity: the text. “We have the text to guide us, half a dozen stage directions, and that is all. I abide by the text and the demands of the text, and beyond that I claim freedom” (Barker quoted in Williams 144). A man of his word, Barker’s Midsummer used all but three of Shakespeare’s original lines. Out went the insanely illusionist scenery and, for audiences long addicted to excess, in came controversy. Beerbohm Tree’s 1900 MSND As we flit on through the early twentieth century, flying fairy-fast past Austrian director Max Reinhardt’s visually eclectic Shakespeare productions, the influence of Antonin Artaud’s Theatre of Cruelty, his book The Theatre and Its Double, and Bertold Brecht’s Berliner Ensemble productions, past Mickey Rooney as Puck (averting our eyes 11 UT Midsummer Night’s Dream from James Cagney and Louis Armstrong as Bottoms), we come to Peter Hall’s 1959 Midsummer in Stratford-upon-Avon. In the aftermath of Modernism and World War II a psychological and sexual unease now gloomed the once-Eden-innocent, fairy-lit forest. "There could be no going back to Athens after Freud. [Post-war p]roductions were ... marked by explorations of repressed dreams, the unconscious, and the irrational— whether as a supposed source of authenticity or as dehumanizing" (Williams 204). And, perhaps for the first time, North American developments influenced British trends in Shakespearian production. Hall was influenced by Tyrone Guthrie’s Stratford Festival move back to semi-Elizabethan thrust staging. To Hall new directorial directions were "not a sin but a necessity because the accretions of time have to be stripped away" (Hall quoted in Williams 207). Thus Judy Dench's Titania “[was] costumed as a sensuous, undersea queen, finned, barefoot, and crowned with wild white flowers ... nature's child ... whose fondness for Bottom was sexually playful" (Williams 208). And as the lovers scrambled around the forest, their self-confidence was "steadily and ludicrously turned inside out" (Williams 210). Finally, just as the play itself takes us happily back to where it started—Theseus’s palace—we arrive back where this production history began: Postmodernism. But this time it’s real—and not at all happy. The Polish theatre theoretician Jan Kott’s book Shakespeare Our Contemporary, in which he compares King Lear to Samuel Beckett’s absurdist Endgame and Waiting for Godot, had a dark, bleakening effect on Peter Brook’s 1962 staging of Lear. But that great tragedy is itself bleak. By comparison, isn’t Midsummer a jolly lark?: (Not for Hermia, below.) Kott’s reading of A Midsummer Night’s Dream reflects his general vision of the bleak condition of humankind in a cruel, inscrutable world, void of any metaphysical design and meaning, subject to the terrors of the state 12 UT Midsummer Night’s Dream and the “Grand Mechanism” of a continuingly corrupted human history. Knott characterizes Puck as a manipulator, akin to the devil and to Ariel in The Tempest, whom Kott compares to a soviet KGB agent. He argues that the suddenness of desire in the young lovers and the[ir] absence of individuality … reduces them to mere sexual partners, making the play brutally erotic and very modern. (Williams 215). One can assume that Brook’s Kott-influenced Midsummer would not have amused Queens Victoria or Elizabeth. Played in a white trapezoidal box set with huge ladders and swings (see image below), “it is as though … a husband secured the largest truck driver for his wife … to alleviate the difficulties in their marriage” (Brook quoted in Williams 227). But that was almost forty years ago. Today we mortals live in (as usual) troubled times, and, in the absence of scientific evidence of fairies, we have only ourselves to blame for these troubles. And while Puck will never be wrong when she says, “Lord, what fools these mortals be,” the fact that we allow her to keep saying it (even pay to see her say it!) shows—perhaps—that we know we are fools and want to be reminded. And as long as we know we’re fools, we may actually be less foolish than those who try to fool us think we are. The research for these program notes comes very largely from Our Moonlight Revels: A Midsummer Night’s Dream in the Theatre by Gary Jay Williams. (University of Iowa Press, 1997.) A more detailed version of this production history, including larger illustrative images, can be found at < http://midsummerdream.terapad.com/>. 13 UT Midsummer Night’s Dream Who was Shakespeare? Little is known about William Shakespeare, generally acknowledged as the greatest playwright of all time. In some ways, the lack of information is ironically fitting. Whereas we can draw on personal history to understand and explain the work of most writers, in the case of Shakespeare, we must rely primarily on his work. His command of comedy and tragedy, his ability to depict the range of human character, and his profound insights into human nature add clues to the few facts that are known about his life. Shakespeare was born in April 1564 in the English town of Stratford-upon-Avon. The son of John Shakespeare, a successful glovemaker and public official, and Mary Arden, the daughter of a gentleman, William was the oldest surviving sibling of eight children. Shakespeare probably attended the local grammar school and studied Latin. His writings indicate that he was familiar with classical writers such as Ovid (the source for the story of Pyramus and Thisbe, the play-within-a-play in A Midsummer Night’s Dream). Throughout Shakespeare’s childhood, companies of touring actors visited Stratford. Although there is no evidence to prove that Shakespeare ever saw these actors perform, most scholars agree that he probably did. In 1582, at the age of 18, Shakespeare married Anne Hathaway, the daughter of a farmer. The couple had become parents of two daughters and a son by 1585. Sometime in the next eight years, Shakespeare left his family in Stratford and moved to London to pursue a career in the theater. Records show that by 1592, he had become a successful actor and playwright in that city. Although an outbreak of plague forced the London theaters to close in 1592, Shakespeare continued to write, producing the long narrative poem Venus and Adonis and a number of comedies. By 1594 the plague was less of a threat, and theaters reopened. Shakespeare had joined a famous acting group called the Lord Chamberlain’s Men, so named for their patron, or supporter, a high official in the court of Queen Elizabeth I. One of the first plays Shakespeare wrote for this company was Romeo and Juliet. In 1598 Shakespeare became part owner of a major new theater, the Globe. For more than a decade, Shakespeare produced a steady stream of works, both tragedies and comedies, which were performed at the Globe, the royal court, and other London theaters. However, shortly after the Globe was destroyed by fire in 1613, he retired and returned to Stratford. The Globe Theatre: 14 UT Midsummer Night’s Dream Fairly wealthy from the sales of his plays and from his shares in both the acting company and the Globe, Shakespeare was able to buy a large house and an impressive amount of property. He died in Stratford in 1616. Seven years later the first collection of his plays was published. 15 UT Midsummer Night’s Dream Elizabethan Fairies and Folk Customs A Midsummer Night’s Dream is associated with two traditional occasions of festivity: May Day and Midsummer Eve. The first of these paid homage to the arrival of spring and symbolically reaffirmed a relationship between human and natural cycles. As such it was essentially a fertility rite and thus invariably associated with courtship and marriage. A Puritan writer of Shakespeare’s time, John Stubbes, gives perhaps the most vivid picture of the form its celebration took in sixteenth-century England: Against May … all the young men and maids, old men, and wives, run gadding overnight to the woods, groves, hills, and mountains, where thy spend all night in pleasant pastimes; and in the morning they return, bringing with them birch and branches of trees to deck their assemblies withal. … But the chiefest jewel they bring from thence is their Maypole, which they bring home with great veneration, as thus; they have twenty or forty yoke of oxen, every ox having a sweet nose-gay of flowers placed on the tip of his horns. And these oxen draw home this Maypole, which is covered with flowers and herbs, bound around about with strings from top to the bottom, and sometimes painted with variable colors, with two or thee hundred men, women, and children following it with great devotion. And being thus reared up with handkerchiefs and flags hovering on the top, they straw the ground around about, bind green boughs about it, set up summer halls, bowers, and arbors hard by it. And then they fall to dance about it, like as the heathen people did at the dedication of the idols. The holiday of the play’s title is one of the oldest and most popular of the pagan rites observed in sixteenth-century England. It was originally a worshipping of the sun at the peak of his summer powers; but by Shakespeare’s time it had become a night of rural festivity associated with magic and enchantment. The rituals connected with it were numerous and included all-night vigils in woods and fields; the collecting of herbs and flowers which were believed to be able to cure sickness or bring luck or reveal one’s future lover; the building of fires; and the carrying of torches in procession. It was a time also when illusions were common, and when mischievous spirits were abroad playing strange tricks upon humans. One of the most notorious of these was the misleading of men and animals by the sprite’s becoming a “fool’s fire” or will-o-the-wisp or assuming a trick voice to lure unwary travelers into swamps and ponds. It is through his special association with this kind of mischief that the Puck or Robin Goodfellow is naturally a part of the Midsummer Night’s happenings. A ballad of the time describes this aspect of his activities in language very similar to that used by Shakespeare in his play: Sometimes he’d counterfeit a voice, And travelers call astray. Sometimes a walking fire he’d be And lead them from their way. Robin Goodfellow’s pranks were not, however, restricted to any special season. He was a lone creature, variously called puck, bugbear, pixie, hobgoblin, who was not traditionally connected to the fairy world and certainly owed no allegiance to King Oberon. He was the best-known elf of sixteenth-century rural England, whose activities are best described in the speeches of the First Fairy and himself after his entrance in Act 2, scene 1: the 16 UT Midsummer Night’s Dream frightening of young girls, the skimming of milk, the misleading of travelers, the causing of harmless accidents, and the helping or frustrating of servants and farmers. While he was considered in general as a harmless—if mischievous—country elf, the English attitude to him had in it also the element of fear which associated him with ghosts, witches, and other less friendly supernatural beings, and which is reflected in the play in his speech to Oberon at 3. 2. 385-94. Mabillard, Amanda. "Sources: A Midsummer Night's Dream". Shakespeare Online. 2000. http://www.shakespeare-online.com. 17 UT Midsummer Night’s Dream Imagery in A Midsummer Night’s Dream Nature Nature and animal imagery also abounds in the play, helping to maintain the “enchanted forest” atmosphere. Oberon’s description of the place where Titania sleeps is an example of this imagery: I know a bank where the wild thyme blows, Where oxlips and the nodding violet grows, Quite over-canopied with luscious woodbine, With sweet musk-roses and with eglantine: There sleeps Titania sometime of the night, Lull'd in these flowers with dances and delight; And there the snake throws her enamell'd skin, Weed wide enough to wrap a fairy in. (2. 1. 259-266) Moon Imagery With four separate plots and four sets of characters, A Midsummer Night's Dream risks fragmentation. Yet Shakespeare has managed to create a unified play through repetition of common themes — such as love — and through cohesive use of imagery. Shining throughout the play, the moon is one of the primary vehicles of unity. In her inconstancy, the moon is an apt figure of the ever-changing, varied modes of love represented in the drama. As an image, the moon lights the way for all four groups of characters. The play opens with Theseus and Hippolyta planning their wedding festivities under a moon slowly changing into her new phase — too slowly for Theseus. Like a dowager preventing him from gaining his fortune, the old moon is a crone who keeps Theseus from the bounty of his wedding day. Theseus implicitly invokes Hecate, the moon in her dark phase, the ruler of the Underworld associated with magic, mysticism, even death. This dark aspect of the moon will guide the lovers as they venture outside of the safe boundaries of Athens and into the dangerous, unpredictable world of the forest. In this same scene, Hippolyta invokes a very different phase of the moon. Rather than the dark moon mourned by Theseus, Hippolyta imagines the moon moving quickly into her new phase, like a silver bow, bent in heaven. From stepmother, the moon is transformed in the course of a few lines into the image of fruitful union contained in the "silver bow," an implicit reference also to Cupid's arrow, which draws lovers together. Utilizing the imagery of the silver bow, Hippolyta invokes Diana, the virgin huntress who is the guardian spirit of the adolescent moon. In this guise, the moon is the patroness of all young lovers, fresh and innocent, just beginning their journey through life. This new, slender moon, though, won't last; instead, like life itself, she will move into her full maturity, into a ripe, fertile state, just as the marriages of the young lovers will grow, eventually resulting in children. (The above essay taken from Cliff Notes http://www.cliffsnotes.com/WileyCDA/LitNote/A-Midsummer-Night-sDream-Critical-Essays-Moon-Imagery-in-A-Midsummer-Night-s-Dream.id-78,pageNum-166.html) 18 UT Midsummer Night’s Dream Themes Does Love ultimately triumph? What are the pitfalls of Love? As Lysander tells Hermia in Act I, Scene I, "The course of true love never did run smooth" (Line 134). Why is this? Are appearances deceiving? Does father always know best? Egeus orders his daughter Hermia to marry a man she does not love. Hermia protests and runs away. In the end, Egeus is proven wrong? Can we dream the impossible dream? Notable Movie Versions of the Play 1. 1999 directed by Michael Hoffman with Michelle Pfeiffer, Kevin Kline (as Bottom) and Calista Flockhart as Helena. 2. 1935 directed by Max Reinhardt with James Cagney as Bottom and Mickey Rooney as Puck. 3. 1968 directed by Peter Hall featuring leading actors from the Royal Shakespeare Company. Famous Dream Quotes Shakespeare coined many popular phrases that are still commonly used today. Here are some examples of Shakespeare's most familiar quotes from A Midsummer Night's Dream. You just might be surprised to learn of all the everyday sayings that originally came from Shakespeare! "The course of true love never did run smooth." (Act I, Scene I) "Love looks not with the eyes, but with the mind, and therefore is winged Cupid painted blind." (Act I, Scene I) "O, hell! to choose love by another's eyes." (Act I, Scene I) "I am slow of study." (Act I, Scene II) "That would hang us, every mother's son." (Act I, Scene II) "I'll put a girdle round about the earth / In forty minutes." (Act II, Scene I) "My heart Is true as steel." (Act II, Scene I) "I know a bank where the wild thyme blows, / Where oxlips and the nodding violet grows, / Quite over-canopied with luscious woodbine, / With sweet musk-roses and with eglantine." (Act II, Scene I) "A lion among ladies is a most dreadful thing." (Act III, Scene I) "Lord, what fools these mortals be!" (Act III, Scene II) "The true beginning of our end." (Act V, Scene I) "For never anything can be amiss, / When simpleness and duty tender it." (Act V, Scene I) 19 UT Midsummer Night’s Dream Study Questions 1) How does Shakespeare use different forms of language? Prose, blank verse, and rhyme are used to differentiate between characters (i.e. fairies and mortals; nobility and rustics) or to create other effects (increased solemnity or silliness; poetic effects). 2) There are four plot levels in A Midsummer Night's Dream: the royal wedding of Theseus and Hippolyta; the story of the Athenian lovers, Lysander, Hermia, Demetrius, and Helena; the conflict between the fairies, Titania and Oberon (seconded by Puck); and the efforts of the "Rude Mechanicals," Bottom, Quince and company, to put on a play worthy of a royal wedding. Know characters (by name!) in each plot level, and be aware of the ways in which they (the characters and the plot levels) interact. How are they parallel or contrasted? What do the different plot levels have in common? (e.g. a movement from conflict to harmony; the theme of love triumphing over great odds). How does Shakespeare use these parallel plots (and characters) to unify the play as a whole? 3) Acts I and V take place in the "real" world of Athens (by day), Acts II, III and IV in a dream world, the woods outside the city (by night). Why does Shakespeare make use of the two settings? How can each be characterized? Do they serve any symbolic purpose? Who governs each world? What kinds of power are contrasted? Which is ultimately more powerful? (Does one have an effect on -- transform -- the other?) 4) The play begins with a forced marriage, fighting fairies, and thwarted lovers; it ends with a triple wedding and a newly reconciled pair of Fairy monarchs. In this movement from conflict to harmony, notice how marital/erotic love is used as a symbol of social harmony and concord. Note also the imagery of fertility (natural fecundity vs. blight, but also the implicit fertility of the couples who will be united in marriage.) What are Titania and Oberon fighting about at the beginning of the play? (What is the symbolic significance of the Changeling boy?) 5) The story of Pyramus and Thisbe is taken from Ovid's Metamorphoses, stories about magical transformations. What are some of the transformations in the play? Consider both literal transformations ("Bless thee, Bottom! thou art translated!" [III.i.119-120]) and figurative ones (between day and night, discord and harmony, reality and dream, unhappiness and bliss). 6) Trace the references to dreams and dreaming in the play. What do "dreams" represent? Who presides over the dream world (the forest at night)? What is the power of dreams? Can dreams have an effect on "reality"? 7) Characterize the fairies and their magic. To what extent do they represent natural forces (i.e. the power of nature?) What else might they represent? Notice that the fairies' magic takes place at night, and that it is several times compared to (or mistaken for) dreams. To what extent is their "magic" a double of the playwright's magic, making a "dream" come to life on the stage? In this regard, you may want to consider references to 20 UT Midsummer Night’s Dream dreams and dreaming, to magic, and to poetry (e.g. Theseus's conversation with Hippolyta in V.1.1-27), as well as Puck's epilogue. 8) Some think that A Midsummer Night's Dream was first written to be performed at a court wedding. Pyramus and Thisbe is a "play within a play" put on by the "Rude Mechanicals" to celebrate a royal wedding. In Act V, then, we are watching an audience watch a play that is like the play we are watching as an audience. What does this parallelism suggest? What function does the "play within a play" serve? (What is its dramatic significance and thematic relevance to the work as a whole?) Are there parallels between the stories of Pyramus and Thisbe and of the Athenian lovers? (Or with Romeo and Juliet, which dates from 1594-1596 -- the same years as A Midsummer Night's Dream?) In other words, are Bottom and company there only for comic relief, or do they convey a more serious message? If so, what? (Questions from < http://cla.calpoly.edu/~dschwart/engl339/mnd.html> 21 UT Midsummer Night’s Dream Classroom Activities Adapted from ClassZone McDougal Littell, available at http://www.classzone.com/novelguides/litcons/midsumm/guide.cfm Theme Openers Chart. Work in small groups to create a chart that lists different sources of romantic attraction. Be as specific as possible. For example, one column of the chart might list physical attributes, such as sparkling eyes, a delicate complexion, luxurious hair, athleticism, and so on. A second column might list personality characteristics, such as a sense of humor, kindness, intelligence, and so on. Go beyond the obvious in their lists. Each group share should its completed chart with the class. Discuss what the charts reveal about the nature of romantic attraction. Linking to Today: Contemporary Images of Love. Discuss how romantic love is portrayed in contemporary culture. Consider how love is depicted in movies, television shows, commercials, music, and other media. Is love depicted as irrational, or does it have a basis in sound judgment? Is love measured by the excitement it creates or the commitment it elicits? Discuss how popular images of love might influence young people or reflect their own experiences of love. Extracurricular Activities Imagine that you are one of the characters in the play. Write and deliver a speech about the nature of love and its importance in marriage. Use quotes from A Midsummer Night's Dream and refer to incidents in the play. Create a cartoon strip of your favorite scene in the play. Illustrate elements that would be especially difficult to portray onstage, such as the size of fairies and Bottom's fantastic transformation. Research Assignment The Magic of Mythical Creatures. Research a type of mythical creature, such as mermaids, gnomes, leprechauns, golems, or genies. Write an essay comparing the creature that they research and the fairies in A Midsummer Night's Dream. Here Comes the Bride. Work in groups to research and present marriage customs around the world and across the ages. Suggested Procedure: Brainstorm a list of countries and historical periods that you are interested in researching. Ask questions about marriage that should be answered, such as the following: What are the typical ages of brides and grooms? What role do the parents have in the choice of a marriage partner? What financial arrangements are involved? What are the customs of the marriage ceremony and celebration? Divide into small groups. Each group choose a country and a historical period. Group members should discuss and decide among themselves how they will divide work and present information. Possible formats include posters, collages, audiotapes, videotapes, computer presentations, dramatic scenes, puppet shows, lectures, panel discussions, and question-and-answer sessions. Groups should do the necessary research and ensure that information about 22 UT Midsummer Night’s Dream marriage customs is presented clearly and accurately. Some groups may require rehearsal time. Much more information on the UT production can be found at http://midsummerdream.terapad.com/ 23